Dr. Bruce Rothschild’s thesis that rheumatoid arthritis is a communicable disease and that it originated in North America won quick and widespread acceptance in the field of anthropology. He had based his conclusions on the examination of skeletal remains from forty archeological sites from Florida through the central and eastern part of the United States all the way up to Ontario, and he had no difficulty explaining and defending his scientific technique. In medicine, too, many of his colleagues in rheumatology clearly saw what he was trying to express and were very positive and supportive. Predictably, however, there were others who were not.

Those physicians who decided to react negatively were in two camps, and their arguments would have come as no surprise to either Thomas McPherson Brown or Ignaz Phillip Semmelweis. One group said that it is necessary to have an intelligent, communicating patient who is willing to donate body fluids before it is possible to make an intelligent diagnosis, an argument that rules out learning anything from the dead along with a significant portion of the living. The other said it was not possible to differentiate between one form of inflammatory arthritis and another.

The group that raised the latter objection had been working principally on English collections of remains, and in England there is a fair amount of spondyloarthropathy, or arthritis of the spine. Spondyloarthropathy is just as inflammatory as any other rheumatoid form of the disease, and Tom Brown would have considered any such distinctions to be largely irrelevant. But they were important to Dr. Rothschild, who believed that the probable infectious cause of each form of the disease can vary widely, and that the key to eventual treatment may depend on understanding the characteristics and mechanism of each form.

For Dr. Rothschild, one of the principal motives behind his anthropological work was to carry an infectious theory about arthritis to a testable hypothesis. A few years earlier he had published on a vascular aspect of the etiology of the disease, indicating that one of the possible pathways to vascular change is an infectious agent or an allergen, and he also looked at gorillas. When he read of Tom Brown’s original work at the National Zoo, he began to suspect that the disease involved in the gorilla model Tom cited was not rheumatoid arthritis as it is usually defined, but fell into the spondyloarthropathy group, specifically reactive arthritis or Reiter’s syndrome. Rothschild examined the skeletons of ninety-nine gorillas that had been taken in the wild; twenty of them had a pattern of arthritis that was indistinguishable from one particular human variety of spondyloarthropathy, that associated with psoriasis.

The naturalist Dian Fossey, later to be memorialized in the film Gorillas in the Mist, told him that in the wild the animals often had rashes that to her looked like psoriasis. Even when physicians look at rashes, if they’re not dermatologists, the reliability of diagnosis is not very good. Moreover, Rothschild knew there had been a study of cats that showed they can be subject to a rash that immunologically looks like psoriasis when the skin is examined under a microscope—and cats can indeed develop spondyloarthropathy.

To Thomas McPherson Brown, the distinctions between one form of inflammatory arthritis and another may have been meaningful in making a diagnosis, but for the most part he had observed that they seemed to respond fairly uniformly to his antibiotic therapy and so had decided they were of no particular significance to treatment. In that respect, although there were long periods in his career when that view placed him in a very small minority, he was never completely alone; there has always been a fundamental difference in views as to what comprises rheumatoid arthritis. “You put two rheumatologists in a room and you’ll get three opinions,” Dr. Rothschild said of the durable controversy.

The heart of the debate is that there is only a handful of major inflammatory, erosive forms of arthritis that involve more than one joint. The most common of these are rheumatoid arthritis and the spondyloarthropathy group. Diagnosticians have divided on that issue into either lumpers or splitters. Lumpers tend to group people with inflammatory arthritis together; splitters tend to separate them by characteristics. Rothschild acknowledged that the jury was still out on the question of which approach is more appropriate, although for purposes of his etiological research he had clearly sided with the splitters. Tom Brown was a lumper.

To Rothschild the distinction was more than an academic one. If the data on the patients who were being studied in the NIH-sponsored clinical trials were to be redistributed by a splitter as having one disease or the other, he had a strong hunch that the spondyloarthropathy group would be found to respond more dramatically to tetracycline. The frequency of spondyloarthropathy, based on this splitting, is as common as rheumatoid arthritis, and if Rothschild’s forecast proved to be accurate, then the debate between lumping and splitting would become an extremely important issue.

Proponents of the infectious theory are aware that even the portion called rheumatoid arthritis by the narrower definition may have more than one cause. Despite that probability, when a rheumatologist looks at a person with that form of the disease anywhere in the world, the pattern of involvement is inevitably similar. By contrast, with spondyloarthropathy there is considerable variation in the way the disease presents, and in that form the variation may be a clue to causative organisms.

Rothschild was aware of Tom Brown’s theory that one such agent is mycoplasma, but they are so commonplace in healthy people as well as those with rheumatoid arthritis, it is difficult to prove a causative relationship. However, he acknowledged the possibility that there’s something connected to the immune system that allows these ubiquitous agents to become triggers, even though they’re in everybody and most people don’t get the disease. An example of the reactive arthritis phenomenon, clearly genetic in origin, turned up as an accidental by-product of a study related to diarrhea.

For the population as a whole, the frequency of one form of spondyloarthropathy is ordinarily one fourth of one percent. But the diarrhea study showed that for people with certain genes, that frequency proved to be one in four, or one hundred times higher. This revelation not only demonstrates that there are susceptibility factors, it suggests those factors may relate to which organism gets the process started. In that particular variety of arthritis, there are a half dozen organisms that can be responsible, and scientists have not yet broken down their patterns of involvement for a clue to which one may be the villain.

As dramatic as Rothschild’s findings have been for those who believed them, the gradual acceptance in the medical community of rheumatoid arthritis as infectious had evolved independently of Rothschild’s work on the historical etiology of the disease. By the mid-1990s, there also was no longer any question that it is transmissible—although how it’s transmitted was still very much at issue. Research didn’t show it as passing between spouses or in families in a direct manner. On the other hand, there are some other types of diseases, such as barley blight, that involve at least a two-component vector system, and Rothschild suspected inflammatory arthritis was probably among them. That meant two things have to happen at once before the disease could be passed along.

The trigger involved in that transmission has to be either a microorganism or an allergen. Most researchers are cautious in speculating on which specific agent it might be. Rothschild suspected it was a slow-acting agent, but he knew that when researchers looked at such diseases as Lyme arthritis, which is not caused by a slow agent, there were obvious similarities. The mystery was deepened by variations in rate of occurrence and uncertainties about the speed of onset after contact. If it really was a slow agent, the mobility of modern society virtually assured that the enigma would not be unraveled solely from an examination of present-day populations but from antiquity. The causative agent was still hidden among those things, known and unknown, which were common to the sites where it occurred in the far past. The fact that the disease preceded agriculture eliminated a whole series of possibilities and helped narrow the focus of the search.

By the time of the MIRA trials, Rothschild’s research had already convinced him of the need to be much more aggressive in therapy, both by starting earlier and by using stronger suppressive agents. Despite that research, and despite his conclusion that inflammation of the joints is always erosive even if it doesn’t show up immediately on X rays, those stronger agents did not yet include antibiotics. Like many other physicians, Dr. Rothschild was conscious of the issue of liability, and he described himself as a big believer that things should be done under a protocol. But he said he was very pleased that this particular protocol was finally being put to the test.

Liability was never an issue that worried Tom Brown. In the last thirty years of his practice he treated somewhere around ten thousand patients with antibiotics, and he’d never been sued by anyone. That said something about the treatment, but it also said something about Tom Brown. Medicine is based first and foremost on personal relationships. The people who get sued the least are the ones who most nearly fulfill the image and role of the family doctor, who treat their patients as individuals and who are themselves seen as human beings by their patients.

Jessie Dutton of Pottsville, Penn., was diagnosed with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and scleroderma in the summer of 1993, at the age of twelve. A member of her school’s basketball and track teams, she also played the flute and piano, and rode show horses when the two diseases literally knocked her off her feet; she was so crippled by their onset, she had to be carried in to see the doctor. Her mother recalls:

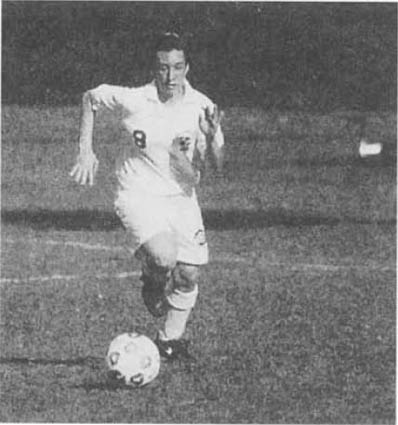

Luckily, we found Dr. Fred Burton, who had studied with Dr. Brown, in Allentown, only an hour from our home; he administered the antibiotic intravenously, and we took care of the oral form at home. By Christmas, Jessie was walking normally, gaining back her weight and getting stronger. A year later she was running again, and by the 9th grade she played varsity soccer, was one of the fastest members of the soccer team, and was back on her horse. We know that isn’t the way these stories usually end, and Jessie is grateful to God for everything the experience has taught her: patience in pain, hope in struggles, and trust when there seems no way out.