One

THE

HISTORY

CONTINUES

To really understand Fell’s Point, Baltimore’s original deep water seaport, one has to dig back into its history. Why do preservationists fight for crumbling, dilapidated old caulker houses? Why does prime real estate lay vacant for long periods? Why are there so many Polish names? Only with a better grasp of the past is it possible to truly appreciate the uniqueness and charm of modern Fell’s Point. (Courtesy of Dan Magus.)

“It’s two o’clock and all’s well,” cut through the silence of the Fell’s Point night when it was a young shipbuilding neighborhood. The tradition of town criers grew up as a means of communication in medieval England. Fell’s Point revived it for a Joshua Barney parade in 1988, and town crier proclamations have been a fixture at special events ever since.

In its infancy, Fell’s Point would have been a noisy place. The days started early. The sounds of sawing, hammering, and carts rolling across the Belgian blocks dominated the area. Today, most noise comes from festivals, occasional construction, and impromptu events, such as the record-breaking snowstorm of 2016, when the city closed down and bored residents gathered on Broadway Square for a massive snowball fight.

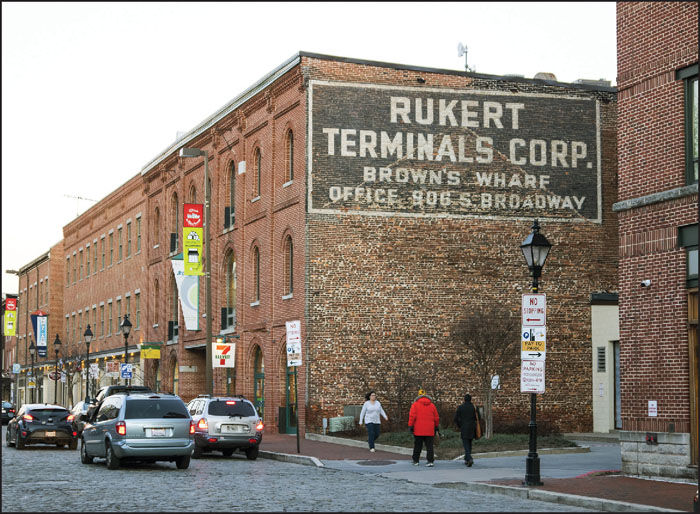

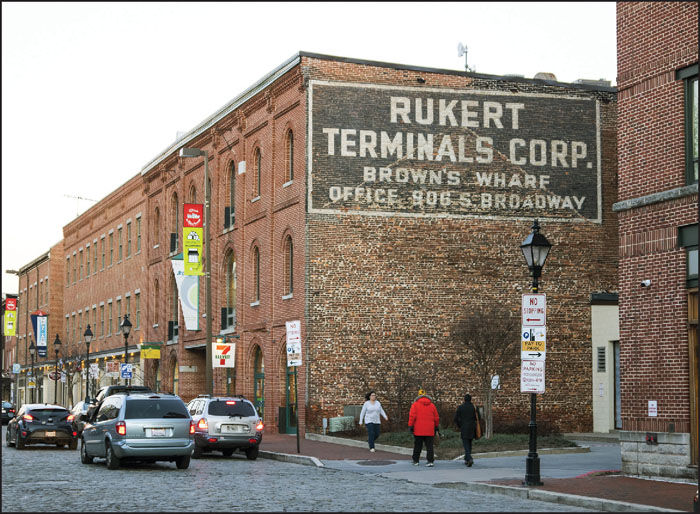

Smells of tar, urine used in tanning, and bat guano for fertilizer would have tested the senses of all who visited the town. Brown’s Wharf was originally built in the 1820s by the Biays brothers, Joseph and James, who primarily used it as a coffee warehouse. Rupert Terminals, one of the companies trading in guano, bought the Brown’s Wharf complex in 1947. This is how it looked from the air around 1980. (Courtesy of the Admiral Fell Inn.)

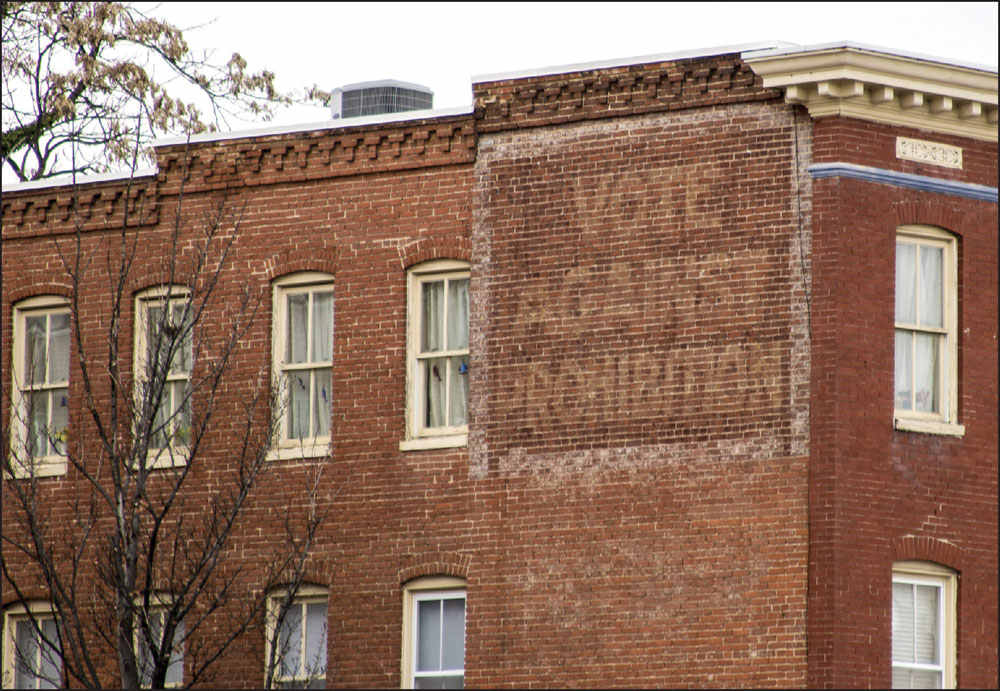

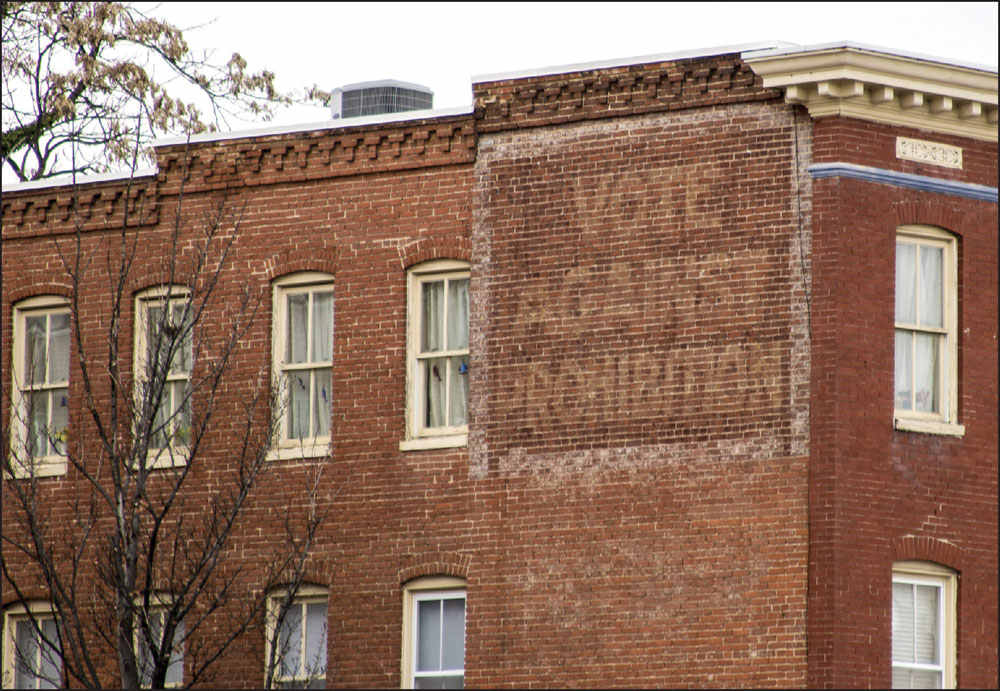

The Brown’s Wharf complex was renovated by Constellation Real Estate in 1989 and is now part of the thriving Thames Street business district, which mixes office space with retail shops, offices, and restaurants. Like many of Fell’s Point’s renovated commercial buildings, the original sign remains painted on the side of the brick wall.

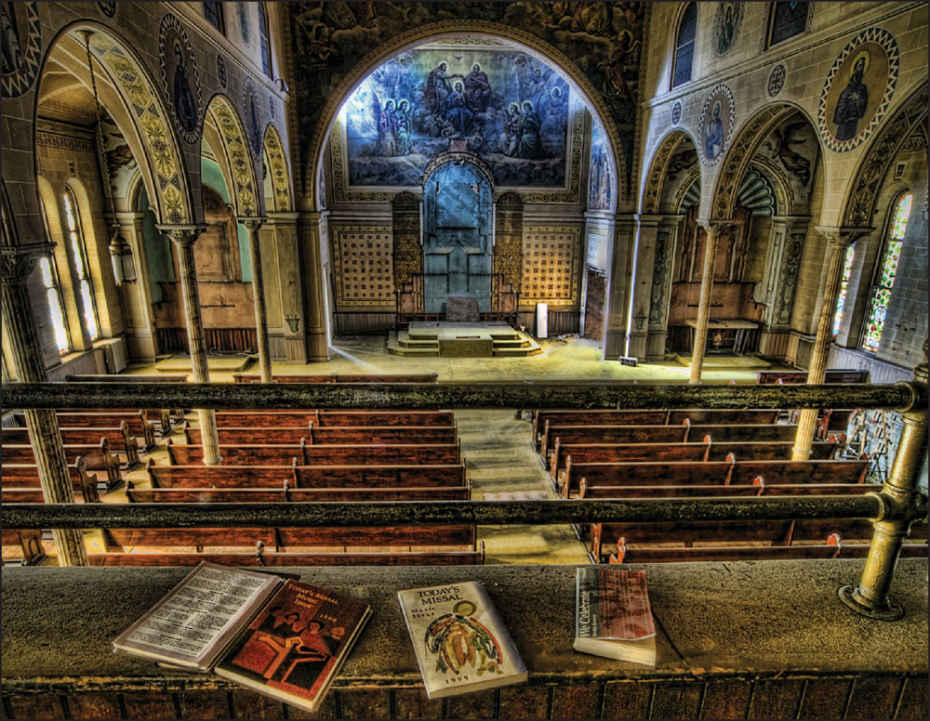

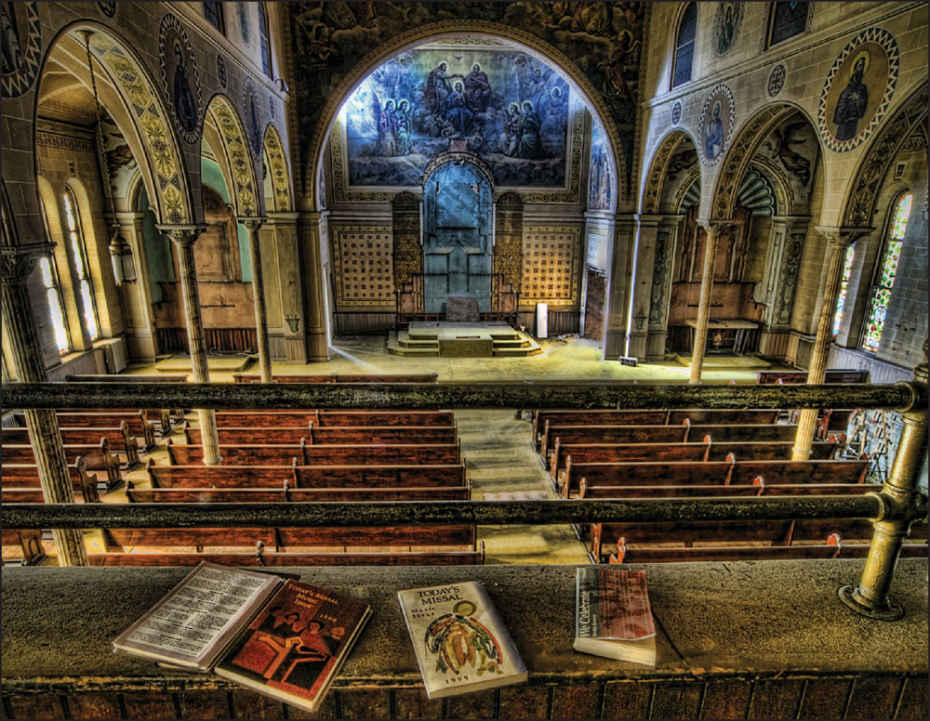

In the early days of Fell’s Point, one heard many accents. French, English, and Irish brogues were common. St. Patrick’s, Baltimore’s second oldest Catholic church, founded in 1792, reflected these changes. Originally, it catered to the Irish laborers and French Catholics escaping the Haitian Revolt and French Revolution. The first three pastors of the church died of yellow fever while helping those afflicted by the sickness. In 1807, the church moved to its current location at Broadway and Bank Street. In 1815, the first free girls’ school was opened next door to the church. The church stood strong as Know Nothing gangs terrorized its parishioners in the 1850s. St. Patrick’s changed with the neighborhood, later catering to German and Polish immigrants and, today, to the Latin American groups who live close by. The church was damaged by an earthquake in 2011, repaired, and is still in constant use.

The business of shipping, pressing of sailors, and the coming War of 1812 were common conversations in the streets and coffeehouses. The London Coffee House, 854 S. Bond Street, built in 1771, is the last surviving Colonial-era coffeehouse in the country. In 1974, it was purchased by Coyne Industrial Laundry, with the George Wells House, around the corner at 1532 Thames Street, and the historic interiors were demolished. In 1997, a demolition notice was posted obscurely behind the buildings. While on a walk, town crier P.J. Trautwein’s dog dragged him there and an outraged community saved the buildings. (Courtesy of the Society for the Preservation of Federal Hill and Fell’s Point.)

Today, the Canusa Corporation has its headquarters in the George Wells House and the London Coffee House is a residence.

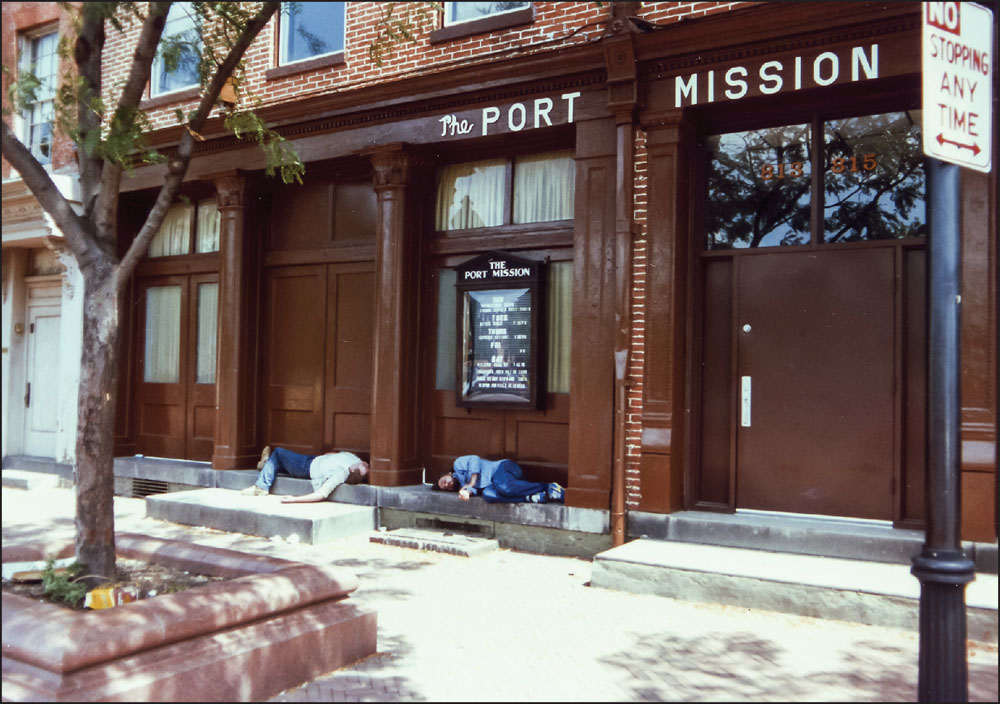

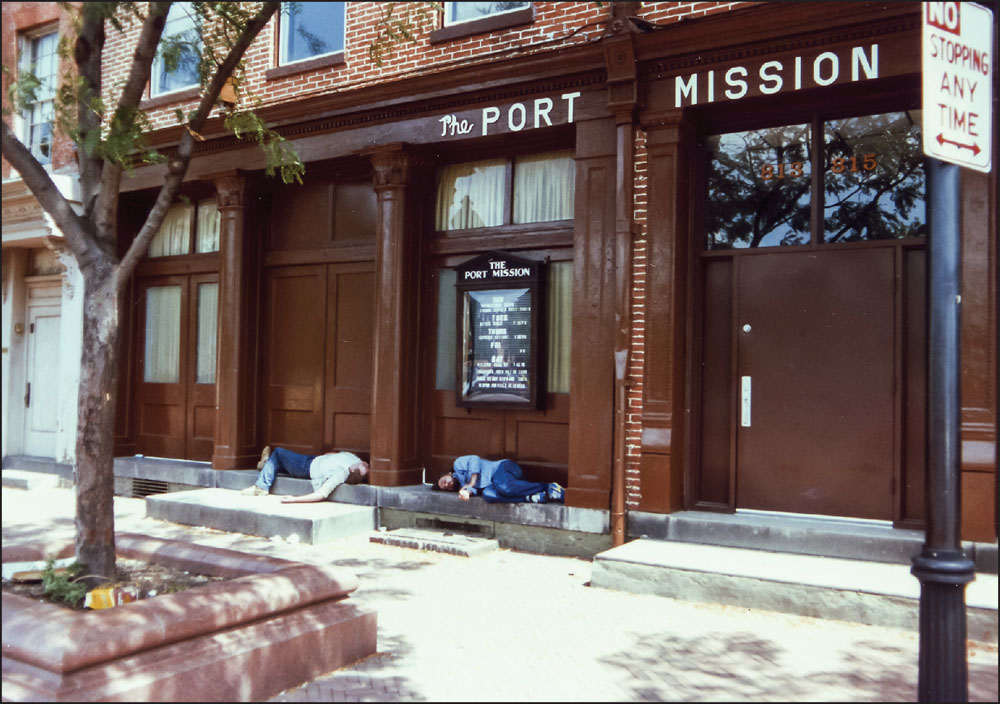

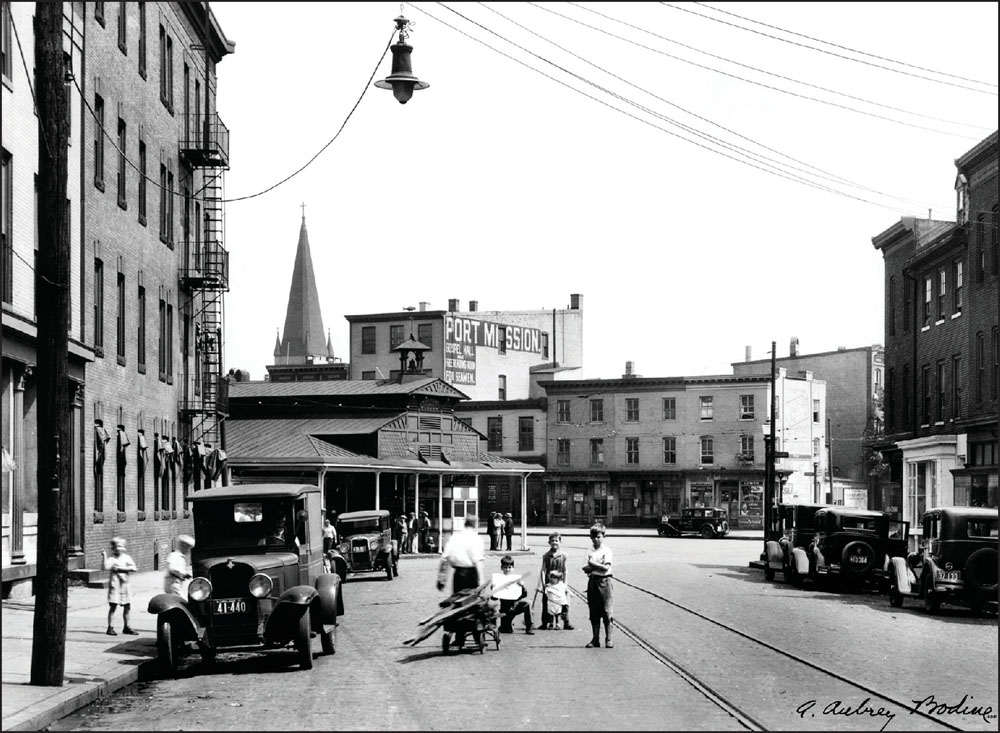

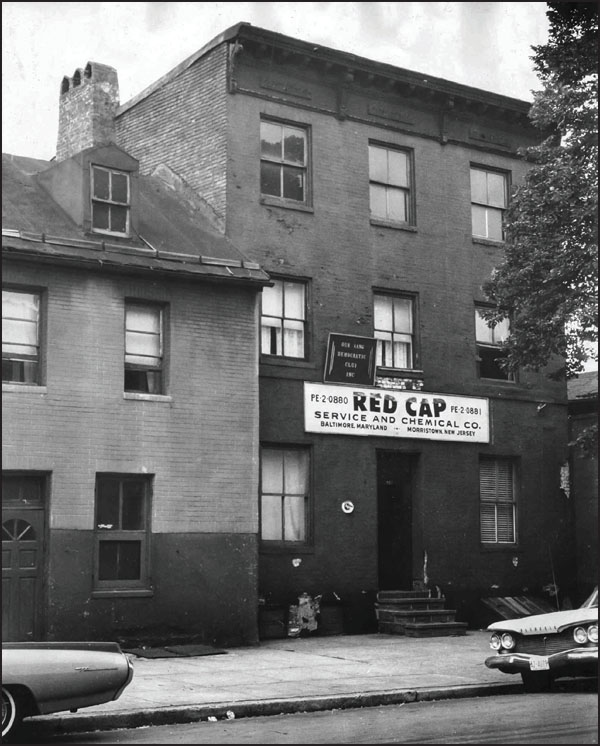

Taverns and boardinghouses swelled with sailors. Some say the term “hooker” derives from the nightly strolls of prostitutes around the “hook” at the west end of Thames Street. Boardinghouses were notorious for “crimping,” or shanghaiing, wayward sailors stupefied with spiked alcohol at the many local bars. The Port Mission on Broadway was founded in 1881 as a refuge for sailors. The mission offered safe boarding, clothes, religious instruction, and cheap rooms. (Courtesy of Alicia Horn.)

The mission outgrew its home and moved across the street into the Anchorage. In 1929, it became a seamen’s branch of the YMCA. It closed in 1955, and for 20 years, the building housed a cider and vinegar factory. It was renovated in the early 1980s into the Admiral Fell Inn hotel by the Eckenstein family.

Slaves working as caulkers were a common sight in early times. The caulking of ships later became a cottage industry dominated by free African Americans. The Levering Coffee House, next door to Harbor Point (center left), was built around 1806 and is the oldest remaining industrial building on the waterfront. (Courtesy of the Admiral Fell Inn.)

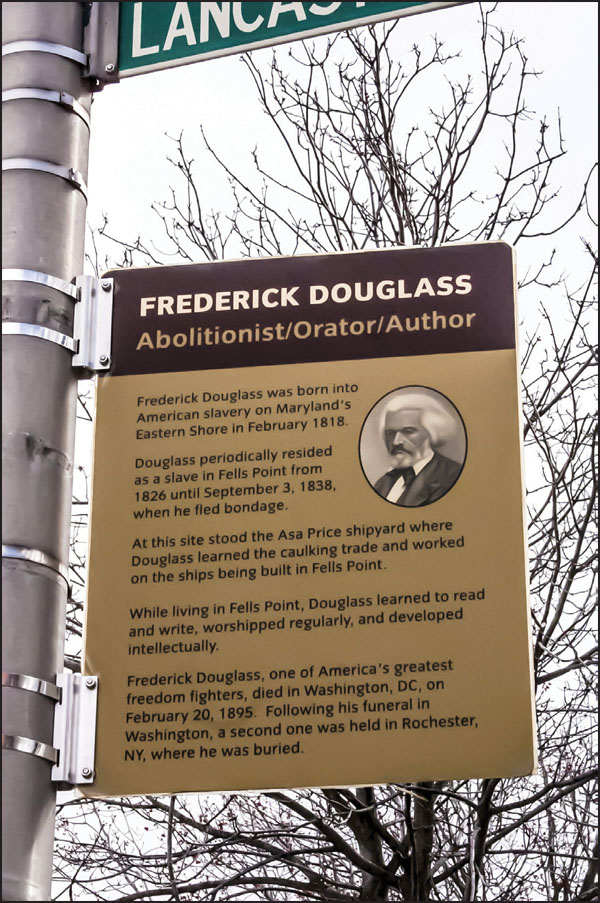

The building is now part of the Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park, created to highlight African American maritime history. Isaac Myers was a free-born African American who created the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company on the site to provide employment to free black caulkers. Frederick Douglass was a slave who learned to read as a child in Fell’s Point, escaped to freedom, and eventually became an influential orator, writer, and statesman.

The Baltimore Schooner was a sleek new design in shipbuilding that created very fast, shallow-draft vessels. This style of ship was perfect for privateering and navigation of the Chesapeake Bay. Demand for the ships was high and kept many “Pointers” employed. The Pride of Baltimore II

, shown sailing by Fell’s Point in 2003, is an authentic reproduction of a Baltimore Schooner.

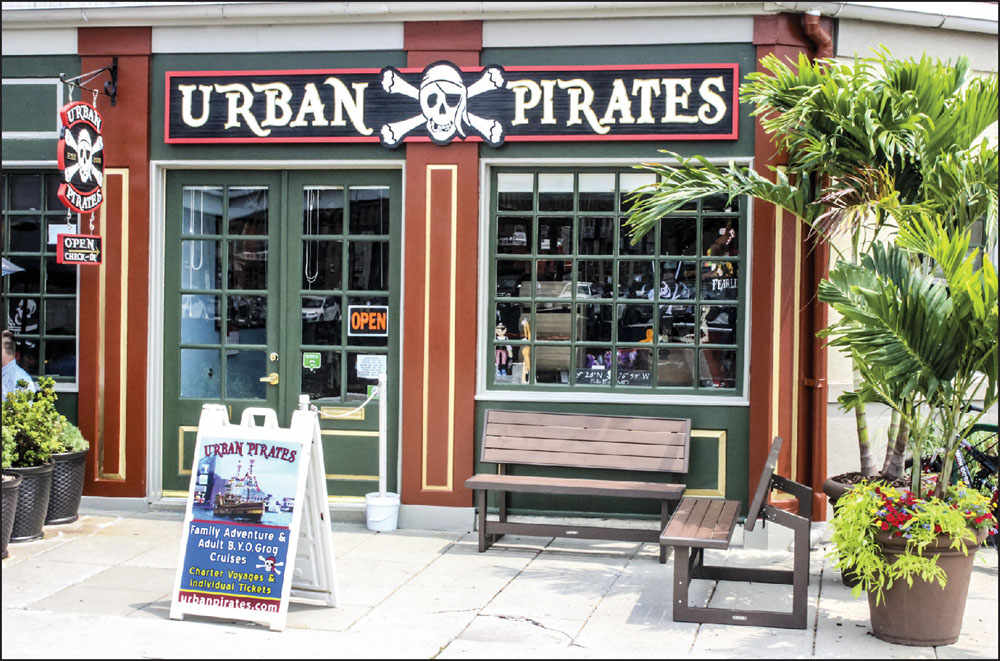

During the War of 1812, Fell’s Point privateers flooded Baltimore with captured British goods. A total of 126 letters of marque were issued to Baltimoreans, who captured over 500 British vessels. Today, Fell’s Point celebrates its maritime heritage in its annual Privateer Festival. The event includes a sea battle/invasion, music, children’s activities, living history exhibits, ship tours and cruises, and a “Pyrate Invasion” pub crawl in the evening.

There are two mistakes one should never make when talking to a Fell’s Pointer. First, never refer to pirates in Fell’s Point. Pirates are criminals who rob and commit violent acts at sea. Privateers are privately owned ships commissioned by a government to attack the ships of its enemies, usually during a war. Fell’s Point’s privateers were operating legally.

The second mistake one should never make when talking to a Fell’s Pointer is calling the streets cobblestone. Cobblestones are rounded and are gathered from stream beds. Fell’s Point is one of only a few remaining areas in the world with Belgian block streets made from rectangular quarried stones. Ships sailing to Europe filled with tobacco cargo often returned only partially full. Stone was used as ballast to keep the ships upright because it could be sold at the destination.

Fell’s Point was forced to adapt as the use of steam engines and the rise of American industry caused a slowdown in shipbuilding in the mid-1800s. South Broadway Pier, at the center of the Fell’s Point waterfront, has been a city-run wharf since the early 1800s. Originally an immigrant ferry stop made of wood, it later became a police station and then a police and fire boat dock. This is the pier in 1968. (Courtesy of Ruth Gaphardt.)

The current Broadway Pier was built in 1992, financed partly by the sale of the engraved bricks that adorn it. In addition to boats, it hosts festivals, films, dance performances, yoga classes, and even the annual Santa visits by tugboat, which are part of Fell’s Point Olde Tyme Christmas.

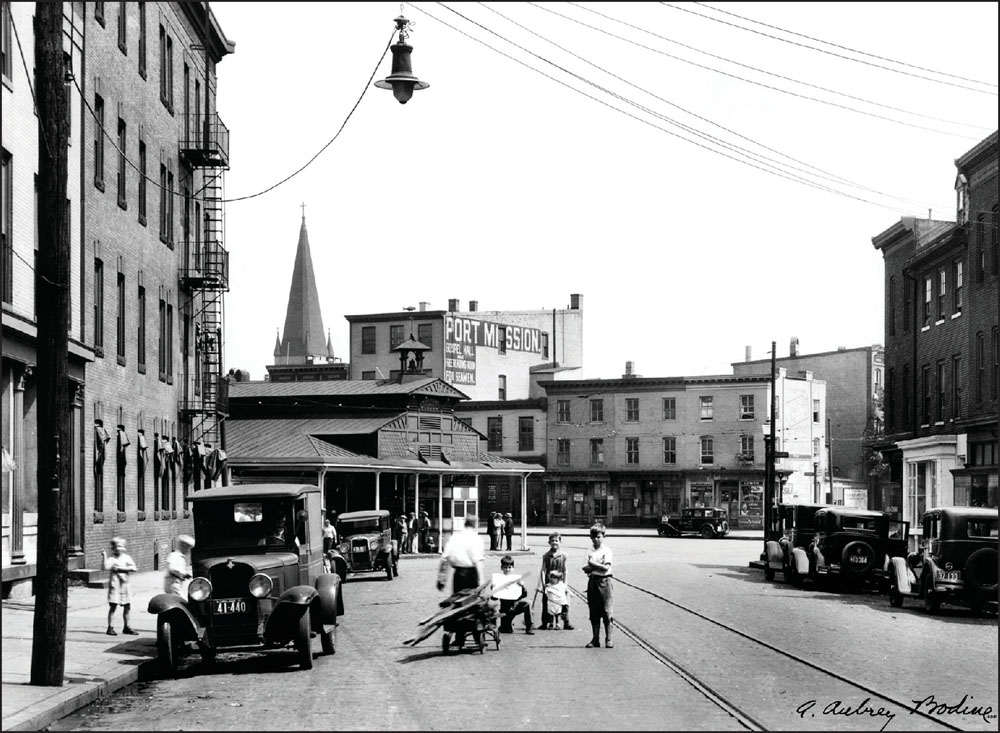

Wars and famine pushed immigrants into the streets of Fell’s Point. The Baltimore Public Market System is the oldest continuously operating public market in the United States. South Broadway Market in Fell’s Point was established in 1786. The market has always featured offerings of the immigrant communities represented in Fell’s Point. (Photograph by A. Aubrey Bodine, © Jennifer B. Bodine.)

The “North Shed” of the Fell’s Point Market had a two-story hall, plus a cupola added in 1865. The second floor burned down 100 years later. Plans to rebuild it as part of the Marketplace at Fells Point project were scrapped for lack of financing and the North Shed still sits incomplete and empty.

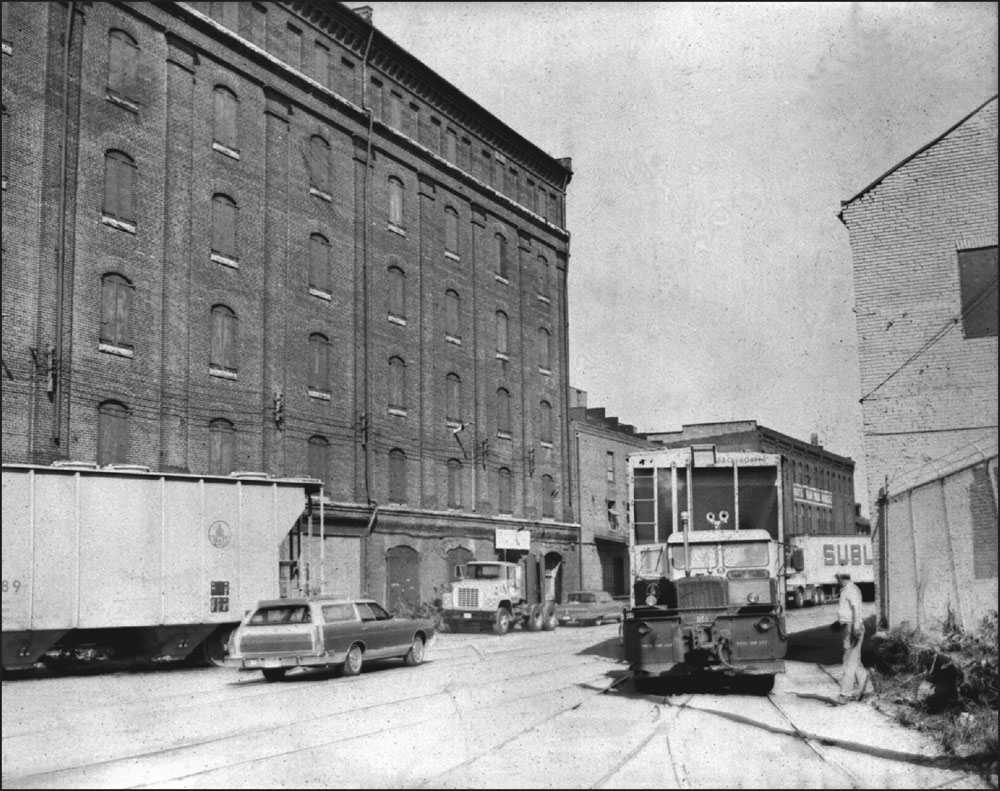

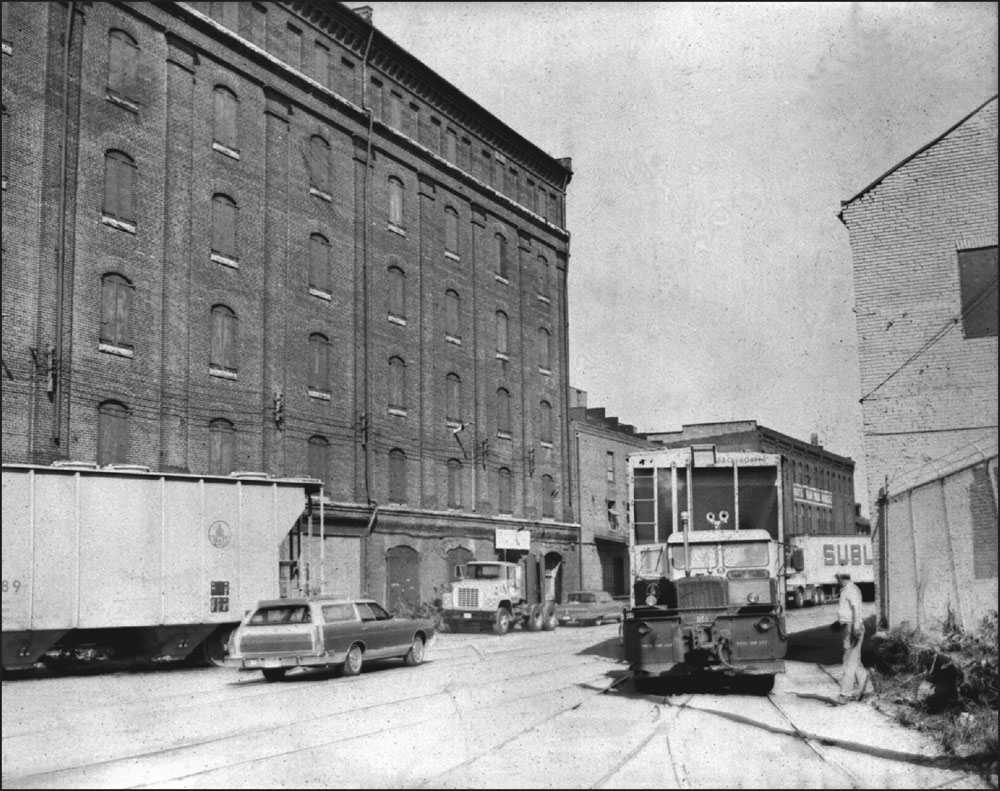

Before 1890, Germans escaping war and Irish escaping famine were the largest groups of immigrants. Shipping took over as the largest enterprise, and wharves and warehouses were built along most of the waterfront. Coffee, guano, and slaves were the commodities. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) built Henderson’s Wharf in 1893. Tobacco from southern Maryland plantations was shipped in by rail down Fell Street, graded, sorted into barrels, stored, and then loaded onto ships. (Courtesy of Herbert Harwood.)

In the mid-1900s, Henderson’s Wharf was used for tire and car storage and then finally abandoned in 1976. The building was renovated in 1990 as an elegant condo residence with the first floor as a 38-room bed-and-breakfast inn.

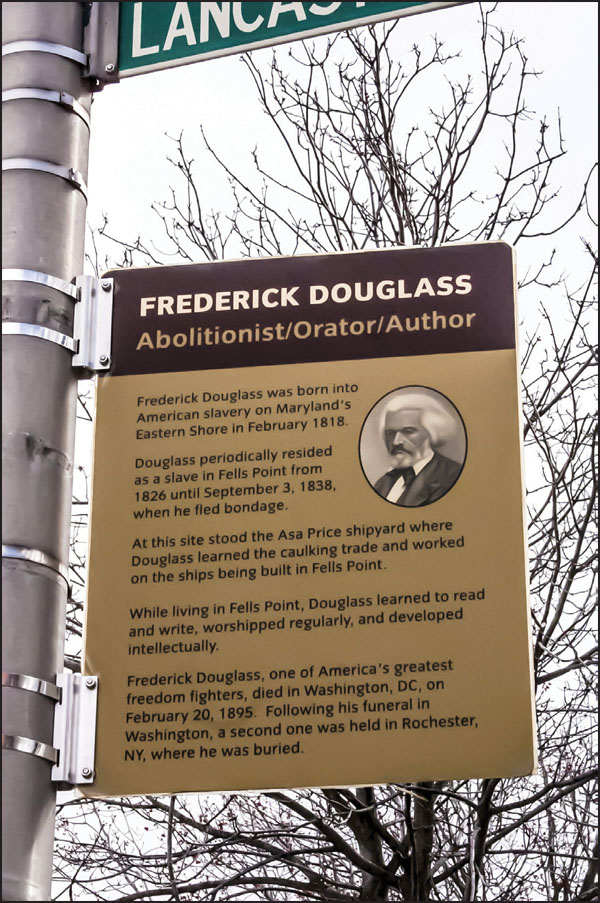

Before the Civil War, Fell’s Point often was a holding area for slaves being sent to other cities, primarily New Orleans. Slave traders used intelligence offices to sell and buy individuals. Packet ships then sent the human cargo to the Deep South. Frederick Douglass, the most important black American leader of the 1800s, spent much of his childhood working as a slave and escaped to freedom from here. He wrote, “In the deep, still darkness of midnight, I have been often aroused by the dead, heavy footsteps and the piteous cries of the chained gangs that passed our door.” This plaque at the corner of Lancaster and Wolfe Streets celebrates the site of the Asa Price shipyard where Douglass learned the caulking trade and worked on ships. The site is now home to Wolfe Street park.

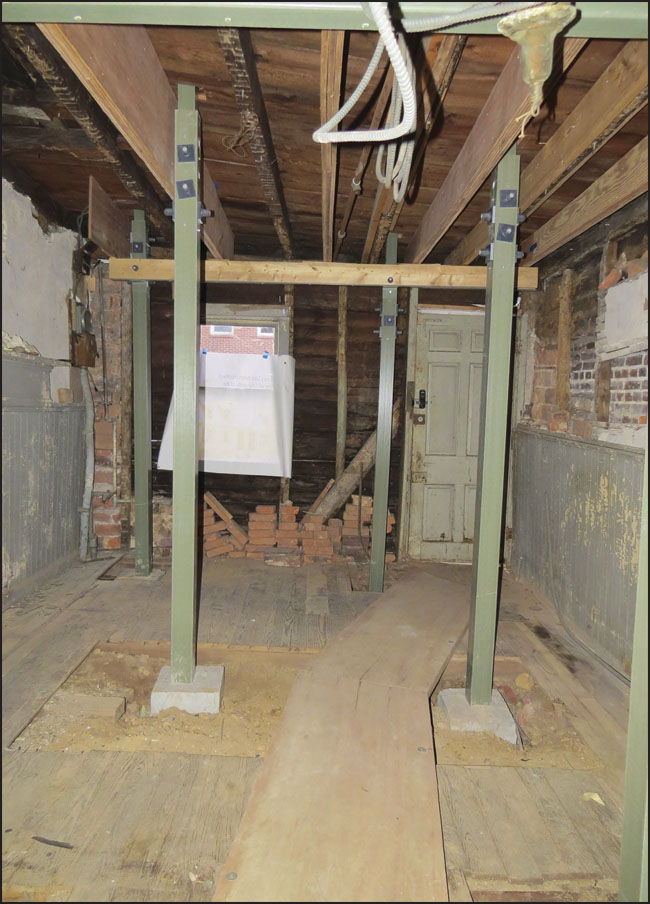

Wood was the most prevalent building material in early Fell’s Point, and in 1798, there were over 400 wood houses in the area. Only eight remain today. These two at 612–614 S. Wolfe Street are owned by the Society for the Preservation of Federal Hill and Fell’s Point and are referred to as the “Two Sisters Houses,” after former owners Mary and Eleanor Dashiell. Baltimore City directories show they were once the home of African American ship caulkers. The directories also reveal that between 1850 and 1870, the concentration of African American caulkers shifted west to Bethel and Dallas Streets. Newly arrived immigrants competed with African American laborers for wage labor jobs, including ship caulking. During the latter part of the 1850s, the African American Caulkers Association became victim to gangs of “job busters” hoping to break the caulking monopoly. (Left, courtesy of Bryan Blundell, Dell Corp.)

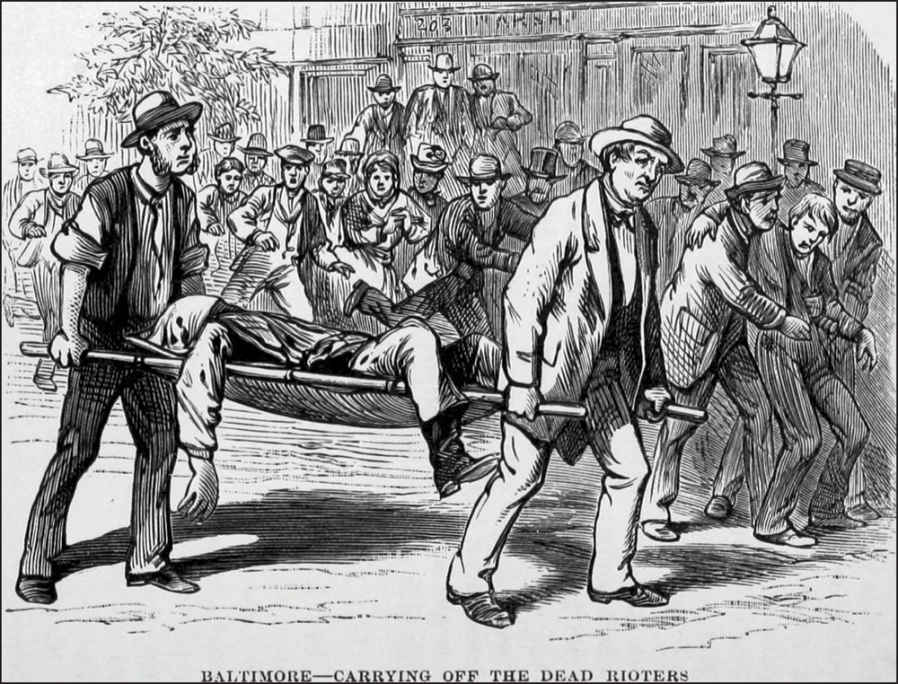

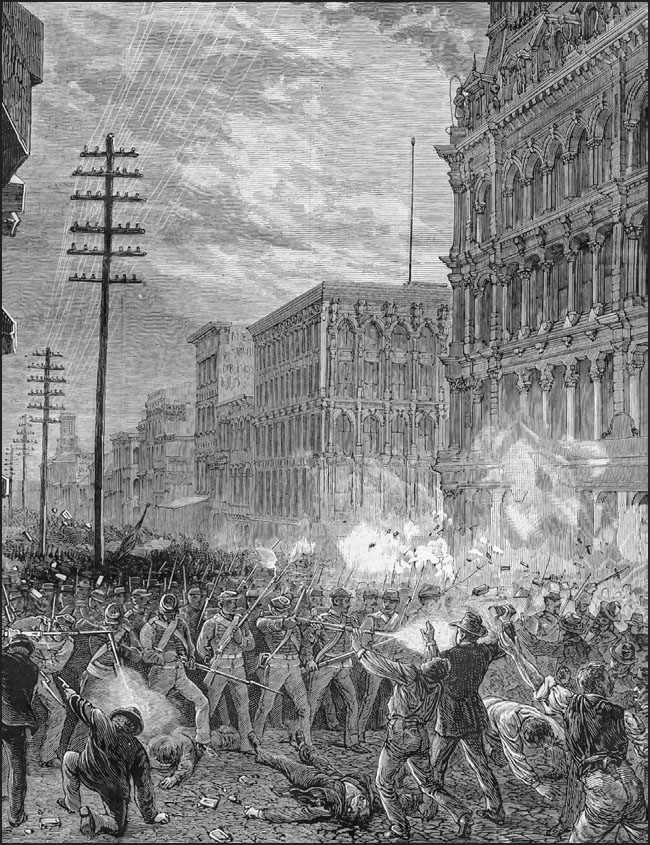

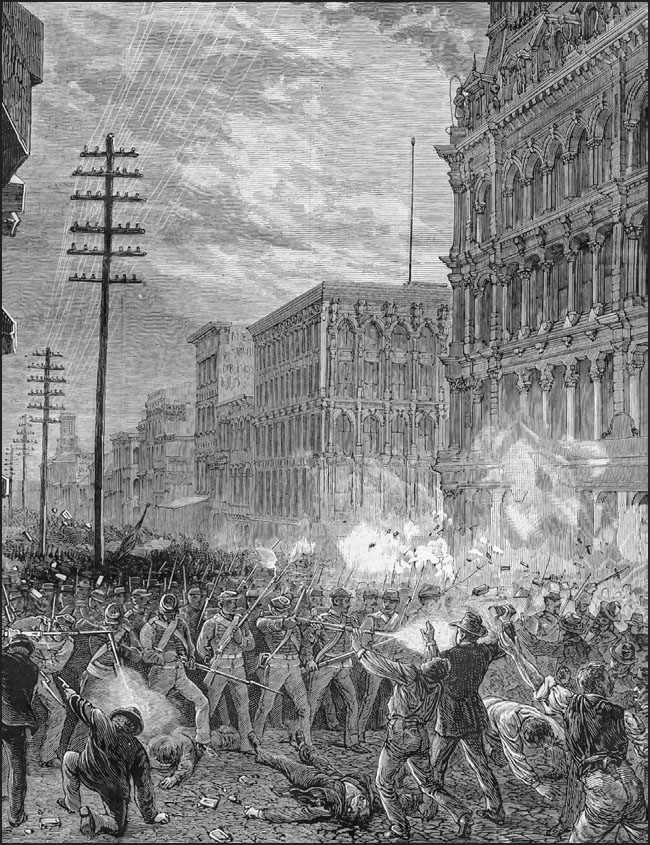

In the 1800s, political gangs struck fear in the hearts of those who voted against them, earning Baltimore the nickname “Mobtown.” Fires were scenes of excitement and violence. Rival fire companies raced to fires, often fighting each other in the street for cuts of insurance money, theft of goods, and neighborhood clout. Towards the 1850s, fire riots were very common. (Courtesy of Library of Congress.)

Although Baltimoreans would prefer to forget this part of their history, remnants of the gangs still exist. In this replica fire mark for 1848 Associated Fireman’s Insurance Co. of Baltimore, the fireman holds a speaking trumpet to issue orders to his mates. Marks like this were displayed on homes to guarantee fire brigades that the insurance company insuring the building in question would reward them for extinguishing the blaze.

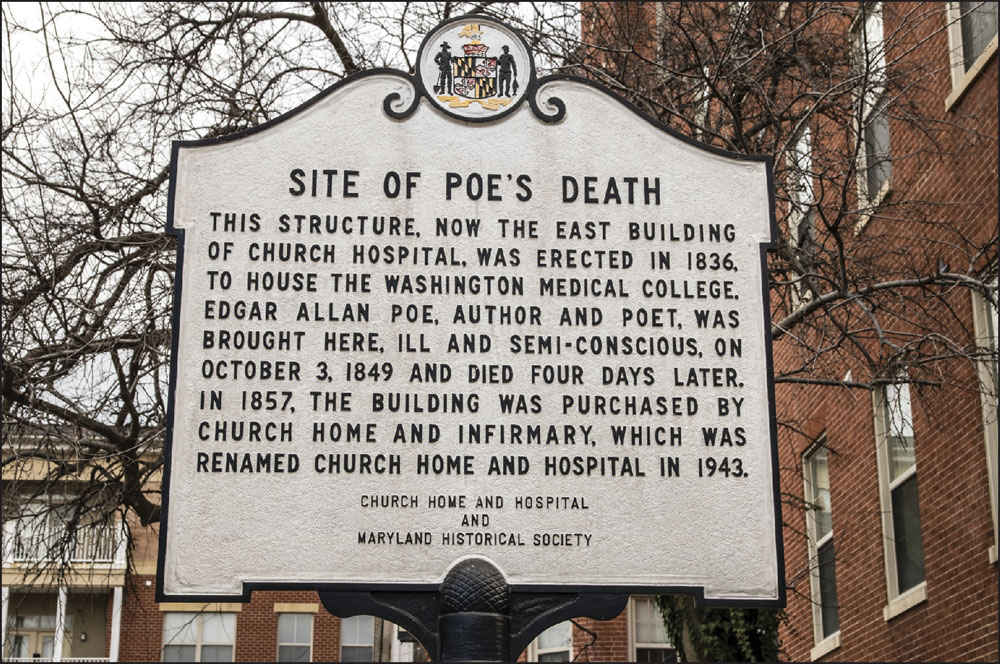

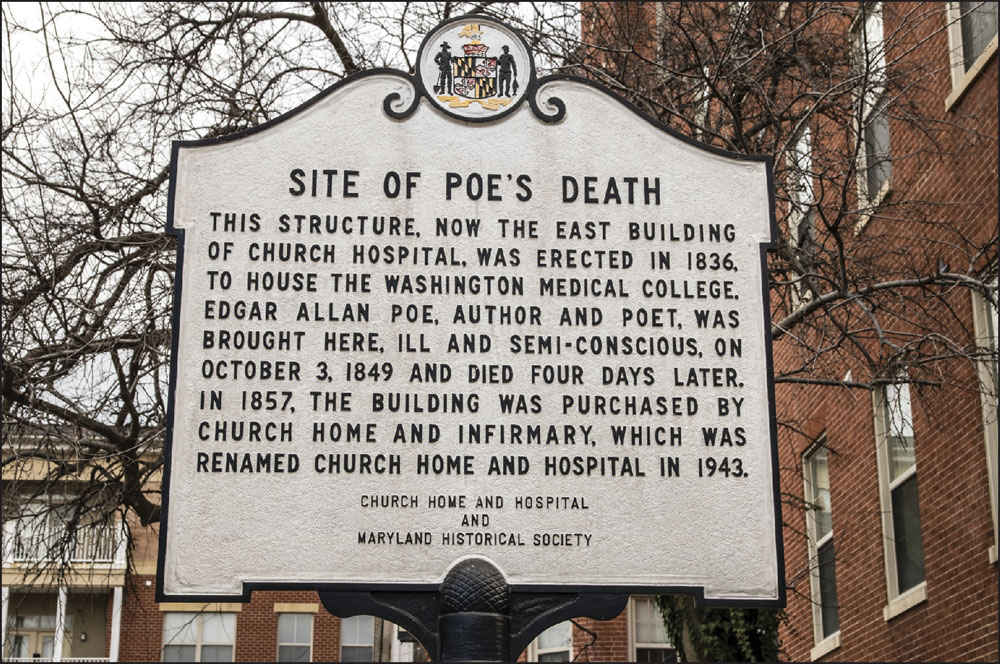

The violence grew and spilled onto elections as fire companies allied with political parties. “Cooping” became common practice—individuals would be kidnapped, robbed, beaten, and given drugs and alcohol to weaken them and were then led by armed men to polling houses and forced to vote repeatedly. Some believe Edgar Allen Poe was cooped; he was found semiconscious and taken to Church Hospital, where he died in 1849.

The street violence culminated in the Pratt Street Riot on April 19, 1861, when Fell’s Point Democratic “tough” George Konig and his Double Pump gang were instigators in the attack. Sixteen people died during the riot, including four Union soldiers. Some of the wounded soldiers were taken to Church Hospital. The hospital closed permanently in 2000 and later reopened as a part of Johns Hopkins Hospital.

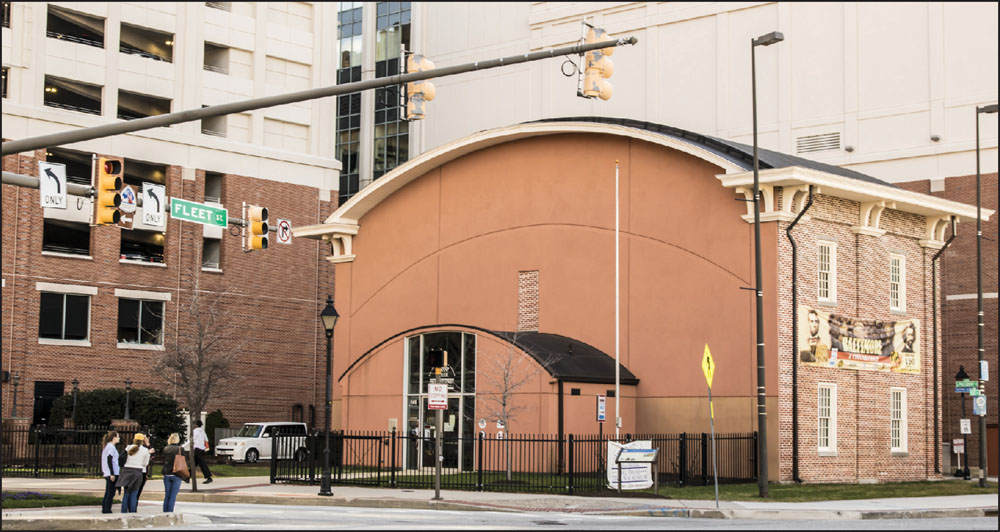

The Pratt Street Riot of 1861 caused the first death of the Civil War. Union soldiers from Massachusetts came by train to the President Street Station, but the city required passengers to be transferred by horse-drawn car to Camden Station on the other side of town. They were attacked en route by an angry mob of Southern sympathizers.

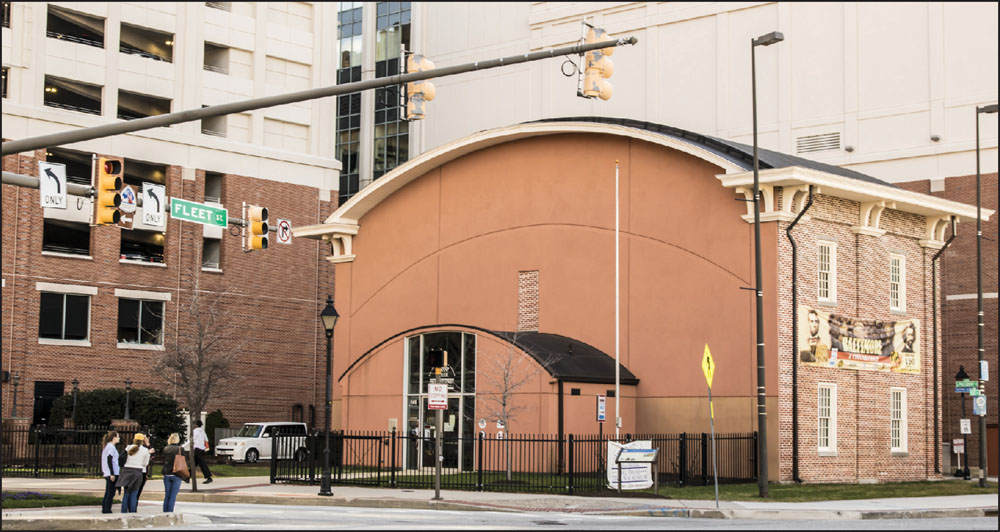

Today, President Street Station is part of the new Harbor East neighborhood. It is the oldest surviving big-city railroad terminal and is home to the Baltimore Civil War Museum.

After the Civil War, Fell’s Point started on a steady decline. Shipbuilding moved out as wooden ships were replaced by metal hulls and steam engines. Alternative jobs were needed. Tyson’s Baltimore Chrome Works opened in 1845, occupying the peninsula in Fell’s Point. At its peak, the plant employed 375 people. Its chrome products were used to tan leather for chrome plating in the making of stainless steel and for colored paints and pigments. (Courtesy of Alicia Horn.)

In 1950, Johns Hopkins researcher Anna Baetjer published a study linking chromate inhalation to workers’ lung cancer based in part on her work at the facility. The plant, then owned by Allied Chemical, ceased operations in 1985. The site became a “brownfield,” a vacant, contaminated industrial site, which allowed large quantities of chromium to migrate into the harbor and groundwater. (Courtesy of TerraServer.)

The Environmental Protection Agency and AlliedSignal entered into a consent decree in 1989 resulting in $100 million in remediation expenses. During the years it sat vacant, the site was used for several Cirque du Soleil performances, as a concert venue, an ice-skating rink, and for local community events such as the annual Fell’s Point Fun Festival. Today, over 1.8 million square feet of development is occurring at Harbor Point. The picture above, taken from across the harbor, shows the scale of the new buildings compared to those on the right in historic Fell’s Point. The skyscrapers drilling through the protective cap on the old Chrome Works site are watched nervously by Fell’s Point residents, who sometimes lament that Fell’s Point has lost its “point.” (Above, courtesy of Kraig Greff.)

Baltimore became the center of the American canning industry in the late 1800s. Canning operations took over Fell’s Point wharves and warehouses. The National Can Company was one of the largest. Several of its original structures date to the 1880s, and for over 70 years, the complex housed packing and can-making operations. The plant closed in the 1970s and was remodeled into apartments in 1981.

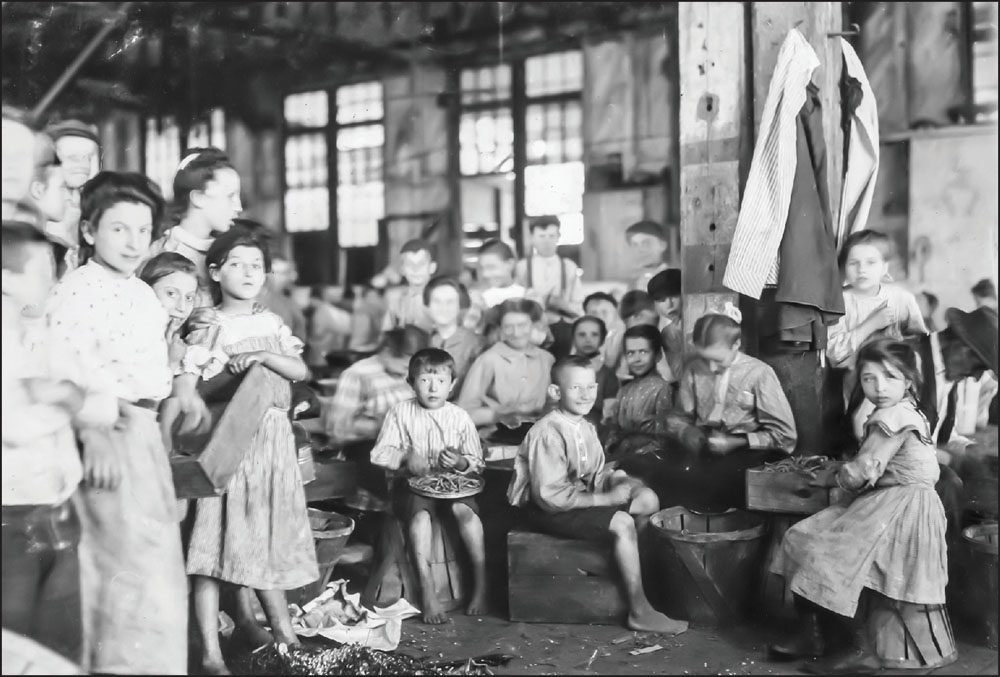

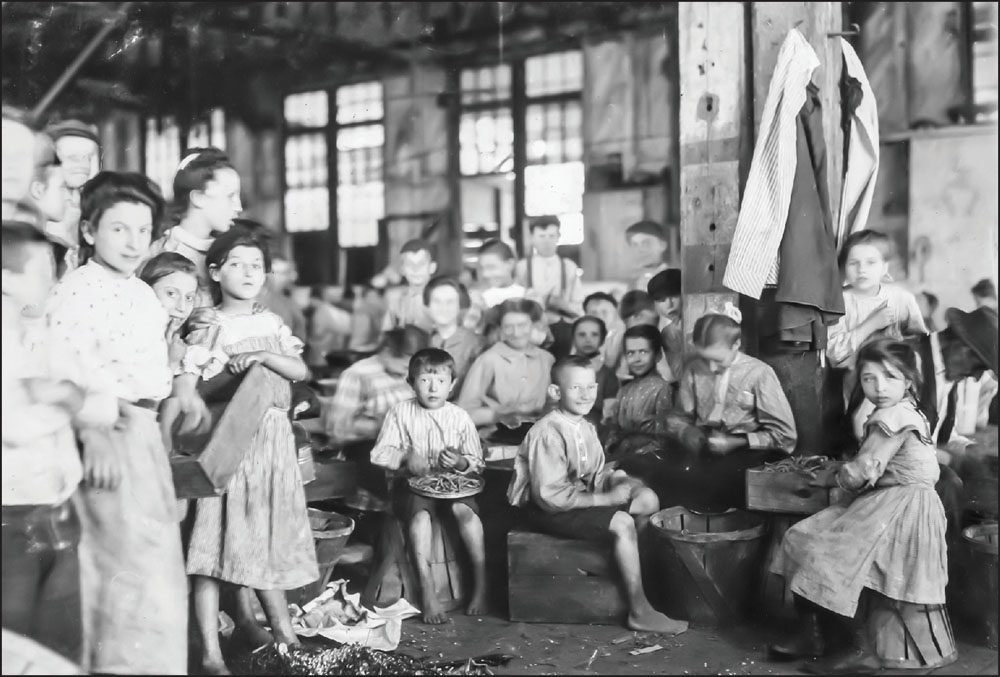

Oyster shucking and canning became the primary occupation of women and children of the Point. This photograph of workers at the J.S. Farrand Packing Co., located at the foot of Wolfe Street, was taken by Lewis Hine, whose images were instrumental in changing child labor laws in the United States. (Courtesy of Library of Congress.)

Immigration changed in the Point in the late 1800s. Poles and Italians became the next wave of immigrants. Both groups searched for manual labor jobs in the area. St. Stanislaus Kosta Church was built in 1889 to serve the growing Polish community. In 2000, it closed due to declining parishioners, and its beautiful interior and historic organ were demolished. (Courtesy of Steven Dembo.)

The Franciscan Friars, who owned the church when it closed, planned to demolish it to allow for a condo development, but the Society for the Preservation of Federal Hill and Fell’s Point was able to have the historic building officially protected under CHAP (Commission for Architectural and Historic Preservation). The building, minus its steeple, is now the home of Sanctuary Bodyworks and the New Century School.

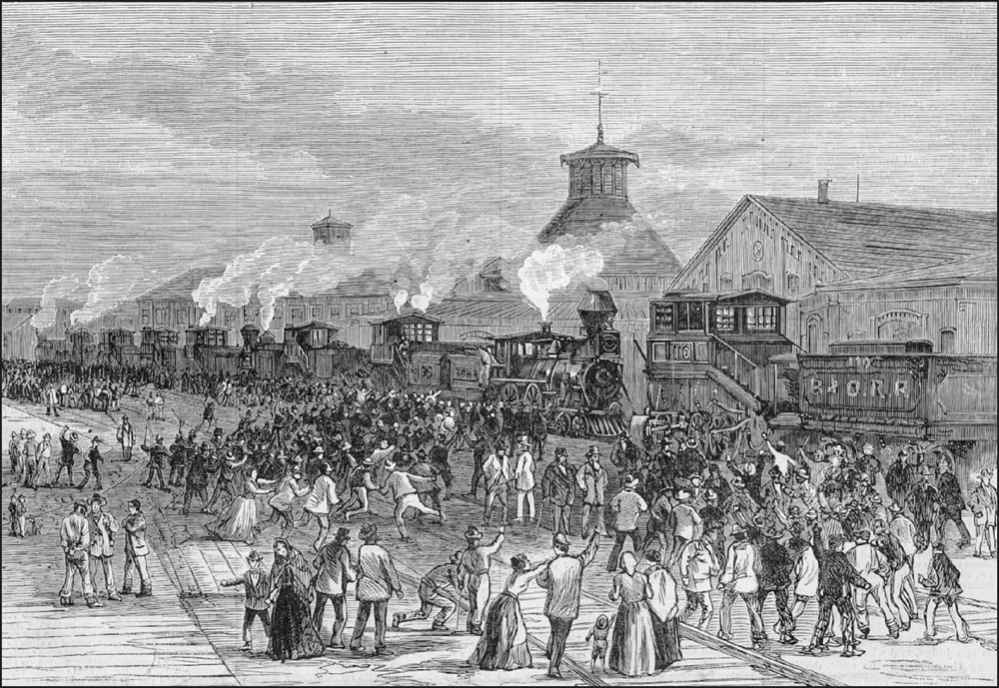

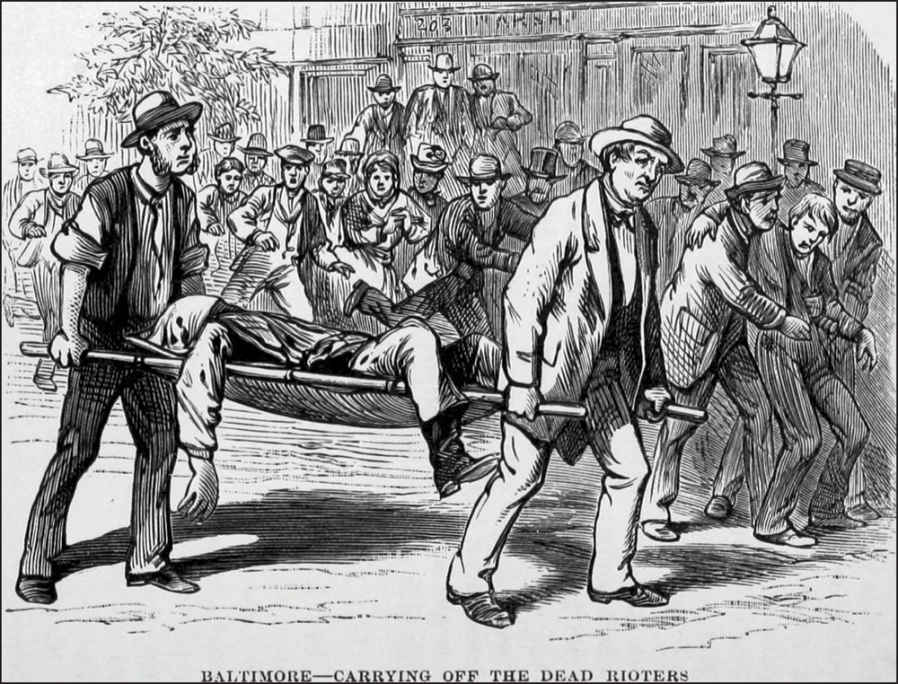

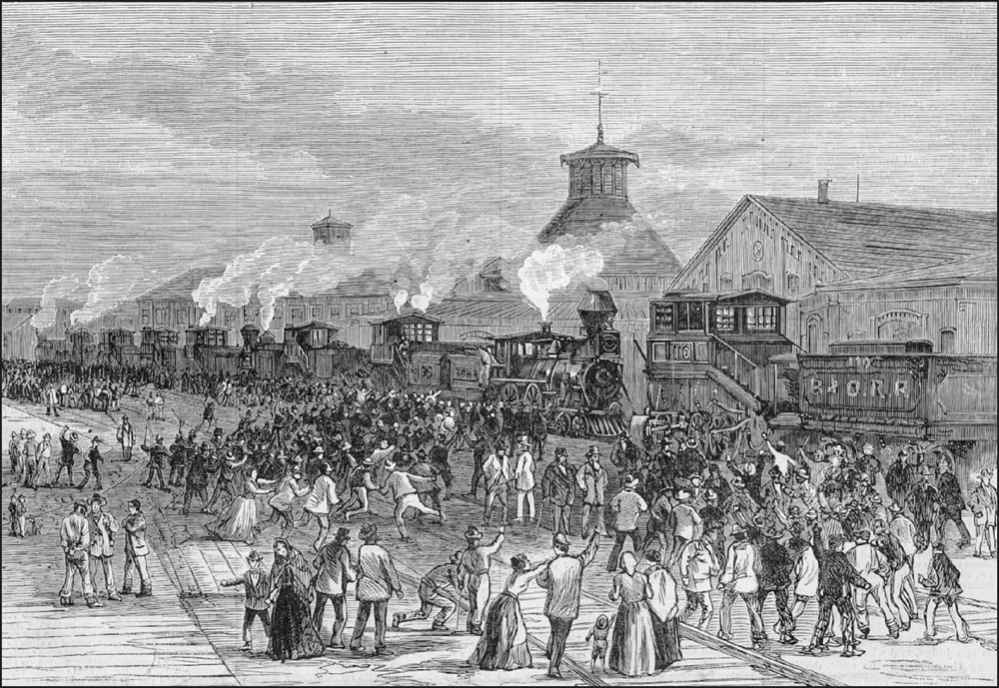

In the late 1890s, workers were attracted by the railroad, canning, the chrome works, and Sparrows Point Pennsylvania Steel Company. Labor relations became the hot topic in the many Polish taverns. The great railroad strike in 1877 was fresh on their minds. That strike occurred in the midst of a depression in protest over poor working conditions and a 10 percent wage cut by B&O Railroad, then Baltimore’s largest employer. It started in Martinsburg, West Virginia, spread to Baltimore, and exploded into a nationwide strike involving more than 100,000 workers and resulting in the deployment of almost half of the US Army. The strike resulted in 10 dead and 25 wounded in Baltimore. (Both, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

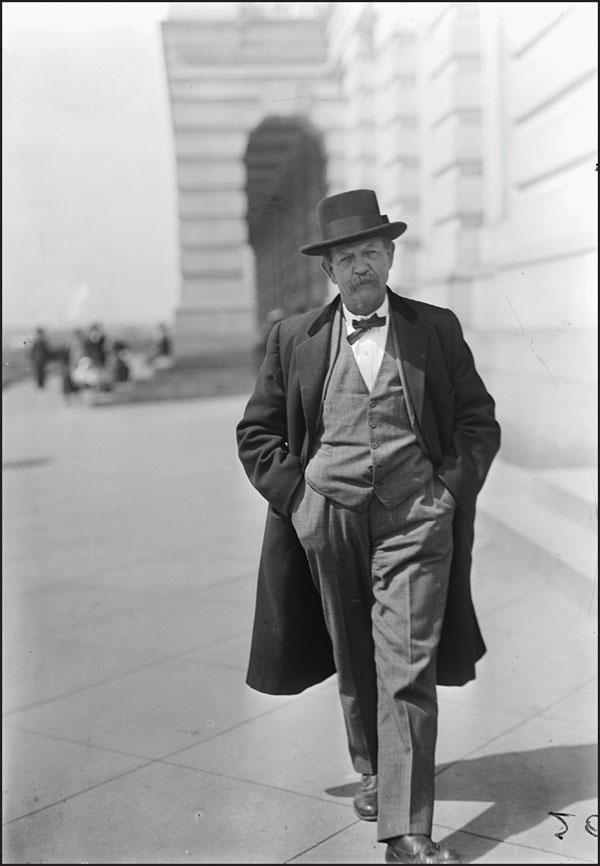

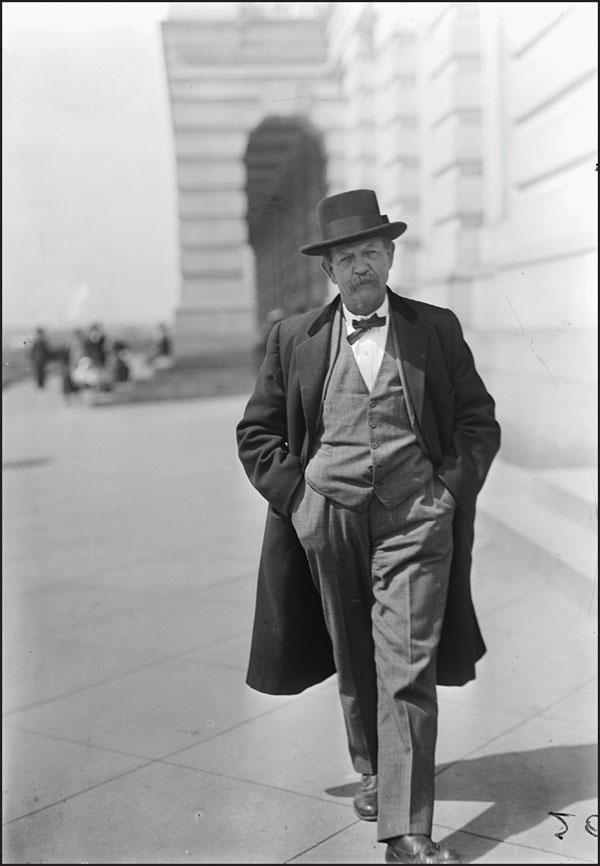

Democrats solidified their hold on the neighborhood, with many union leaders becoming councilmen. One such leader was George Konig Jr., the son of the infamous Democratic “tough” George Konig Sr., who instigated the 1861 Pratt Street Riot. Konig Jr. was involved in multiple unions and eventually became a US congressman in 1910. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

At the end of the 1800s, shipping remained present in Fell’s Point, but shipbuilding was a thing of the past. Many of the areas along the waterfront that were not involved in canning became warehouses, storing goods that were sent inland by railway or shipped overseas. The western edge of Fell’s Point was primarily warehouses and lumberyards waiting for shipping. Today, the area is known as Harbor East, a spectacular new mixed-use development filled with high-rise buildings.

After 1900, Poles and Italians continued to pour into Fell’s Point. The end of Broadway Pier had a ferry station that ferried immigrants from Locust Point to Fell’s Point daily. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

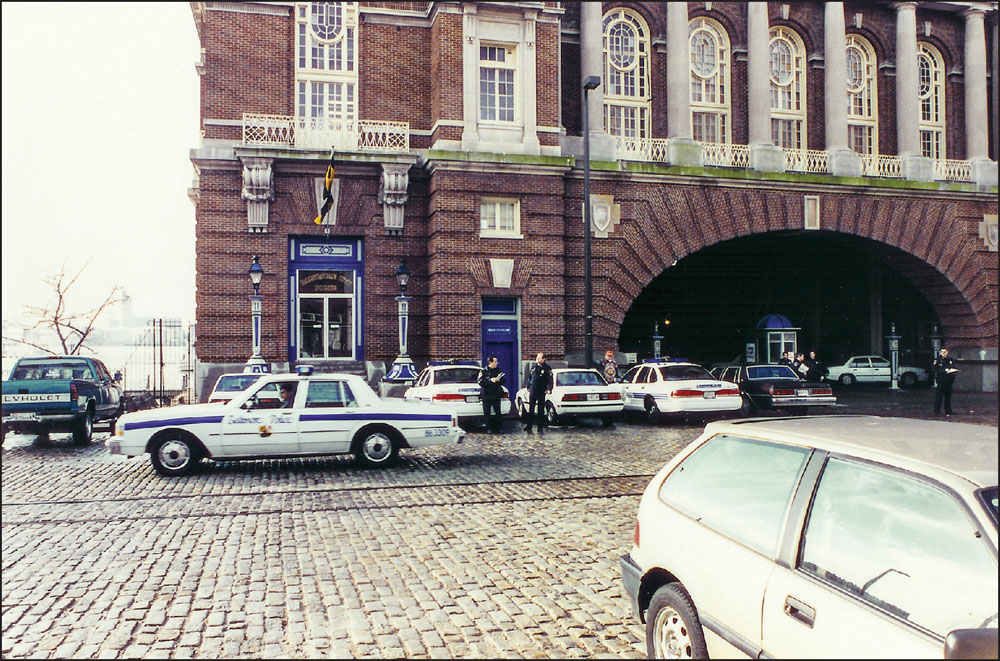

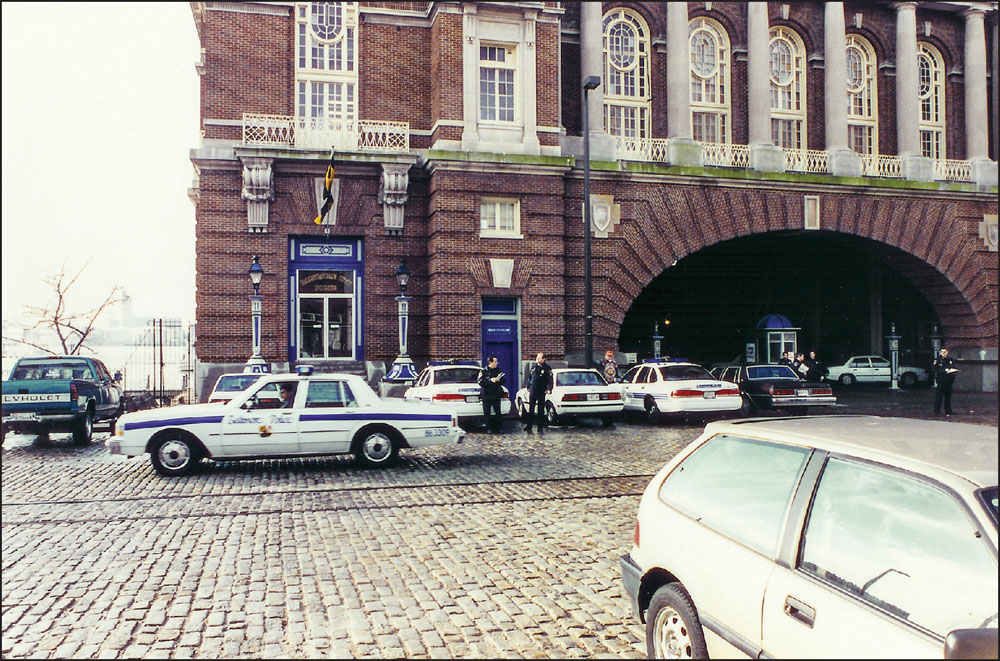

In 1912, Baltimore decided to build a modern cargo facility next to Broadway Pier. To improve community relations, they also included a recreational facility. City Pier, also known as Recreation Pier, was handed over to the “children of east Baltimore” in 1914. While it was open, it hosted many recreational activities, including dancing, playgrounds, basketball, skating, concerts, and dinners. The back side supported commercial shipping, steamboat excursions, and numerous tugboat companies. This is “Rec Pier” in 2001, when Moran tugboats still operated there.

From 1993 to 1999, Rec Pier was the site of the police station featured in the TV show Homicide: Life on the Street

. Considered to be one of television’s most authentic police dramas, the long-running series highlighted many area landmarks and local businesses. (Courtesy of Anne Gummerson.)

After Homicide: Life on the Street

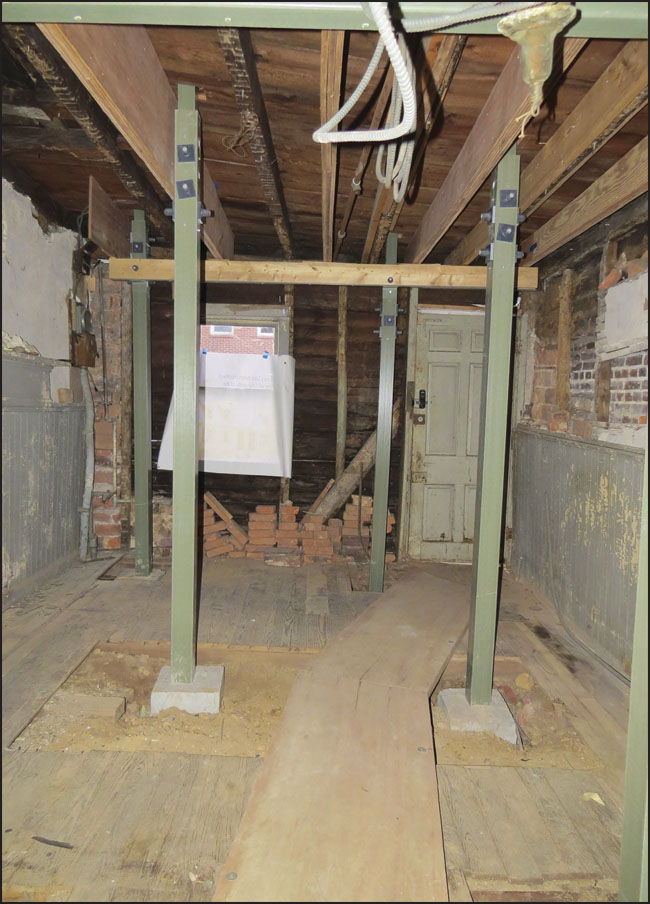

ended, Baltimore City lacked funds to repair the deteriorating pier underpinnings and called for bids to redevelop it. Two years of meetings and spirited debate followed, and in 2004, Baltimore chose a boutique hotel. The hotel was delayed by Hurricane Katrina, followed by the recession of 2008. Finally, in 2014, Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank and Sagamore Development stepped in to renovate and restore the structure, turning it into a boutique hotel with restaurants and shopping. Completion is scheduled for 2017. (Courtesy of Sagamore Development and BHC Architects.)

The Polish heavily inhabited the “foot of Broadway,” while the Italians created “Little Italy” nearby in the old German neighborhood known as Mechanics Row. Polish bars and taverns dominated Fell’s Point. The Polish community continues to have a strong presence in Fell’s Point, as evidenced by the Polish Home Club, Lemko House, Ze Mean Bean Cafe, Krakus Deli, and Ostrowski’s.

The annual Polish Christmas caroling event starts and ends at the Polish Home Club and travels miles through the streets of Fell’s Point, visiting Polish religious sites and prominent Polish businesses. Hundreds—and sometimes, thousands—have attended over the past 60 years, singing, drinking, and ignoring the weather.

Many of the modern bars in Fell’s Point have strong Polish roots. The Horse You Came in On, the Wharf Rat, One Eyed Mike’s, Penny Black, and the Admirals Cup were all once Polish Bars. European attitudes about drinking acted as a major roadblock to treasury agents looking for speakeasies during Prohibition. (Courtesy of Ruth Gaphardt.)

Maryland, “the Free State,” was the only state that did not enforce Prohibition on local levels; only federal agents would enforce Prohibition. Fell’s Point remained a heavy drinking neighborhood. A “Vote Against Prohibition” sign was painted on this building on the corner of Shakespeare Street and South Broadway for all see. It is still visible today.

The International Longshore and Warehouse Union and Seafarers International Union grew in power, and by the mid-20th century were a political force in Fell’s Point. As of 1990, Fell’s Point still had its own office of the International Organization of Masters, Mates & Pilots at 1715 Aliceanna Street. The building is now home to the Blushing Gypsy Women’s Boutique and Fine Arts Gallery. (Courtesy of Alicia Horn.)

Fell’s Point saw union violence again during the 1940s. Waterfront strikes were a common occurrence. More and more ships were unloading in the deeper waters of North Point, and this slow decline caused locals to move out of the city. The “foot of Broadway” was being abandoned. These are several warehouses near the Douglass-Meyers Museum that the community was unable to save. The area is now a parking lot, waiting for development. (Courtesy of Anne Gummerson.)

Anyone driving around Baltimore today during rush hour will complain about the traffic. In the 1960s, Baltimore City tried to avoid that problem by putting in a highway through the city that would have connected Interstate 95 to Interstate 83. This would have gone through Fell’s Point, destroying much of the historic district. The road fight, preservation, and ultimate rebirth of the neighborhood dominated the latter half of the 20th century. (Courtesy of the Society for the Preservation of Federal Hill and Fell’s Point.)

Local residents fearing displacement began to fight the road commission. Local social worker Barbara Mikulski, now a US senator, launched her political career fighting against the road. (Courtesy of Glenn Fawcett.)

Preservationists fought to save the neighborhood through a historic district designation. In 1966, the community started the Fell’s Point Fun Festival to raise money for the road fight, and to draw attention to the historical significance of the neighborhood. This is a photograph from the 1968 festival. Through the efforts of community organizers and preservationists, Fell’s Point became Maryland’s second National Register Historic District in 1969. (Courtesy of Ruth Gaphardt.)

The year 2016 is the 50th anniversary of the Fell’s Point Fun Festival. The two-day free festival, which takes place the first weekend of October, features street vendors, music stages, beer gardens, and kid-friendly activities. It draws several hundred thousand people to the tiny community annually.

Built by merchant Robert Long in 1765 as his residence and office, the Robert Long House is the oldest urban dwelling in Baltimore City. In the 1870s, as with many area homes, the gable roof and dormer were removed to allow expansion to a full third floor, which helped house the growing number of immigrants. This image is from the “road war” era, when the community was considered a slum. (Courtesy of the Society for the Preservation of Federal Hill and Fell’s Point.)

The derelict house was purchased in the 1970s by the Society for the Preservation of Federal Hill and Fell’s Point to provide standing in a legal action against the city to preserve the neighborhood. The society later learned that the house was much older than initially thought and raised over $900,000 to restore it in the early 1980s.

During the 1960s, the City of Baltimore had condemned and purchased large swaths of the neighborhood in preparation for demolition. With property values at an all-time low and the future uncertain, artists began to move to the area. Small boutiques and galleries began to open. (Courtesy of Ruth Gaphardt.)

In the 1970s, as the future again looked brighter, new bars began to push out the old Polish and sailor dives. Leadbetter’s, Berthas, the Cat’s Eye Pub, and Birds of a Feather all opened during this period. These bars catered to younger, wealthier professionals, as the sailors were gone and the area’s poorer working-class residents were being pushed out by escalating property values. (Courtesy of Ruth Gaphardt.)

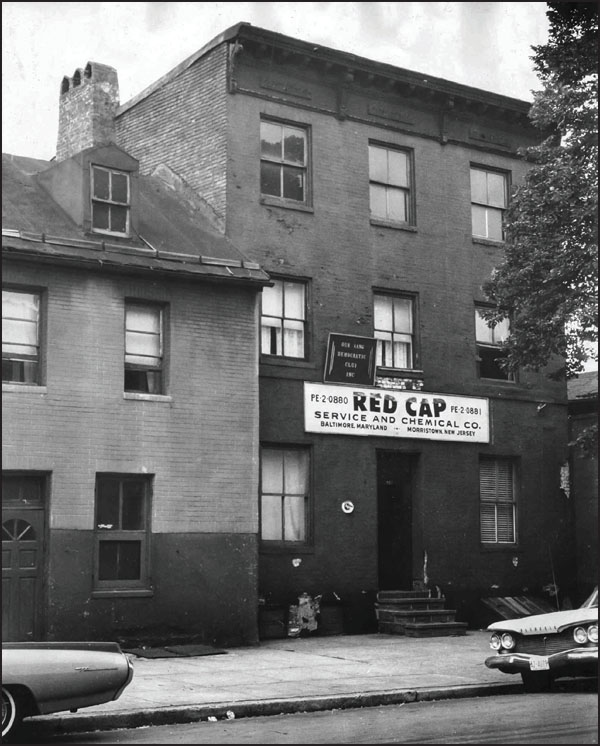

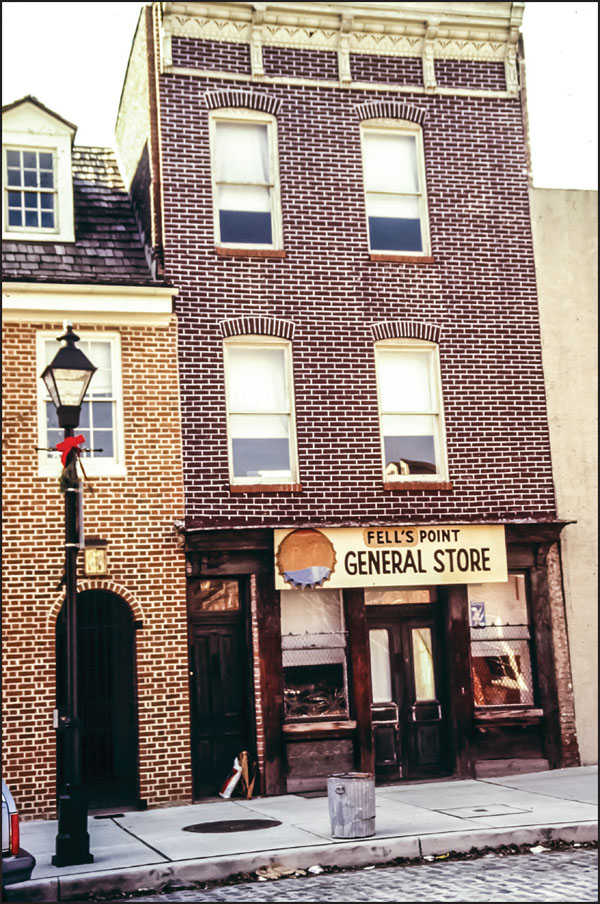

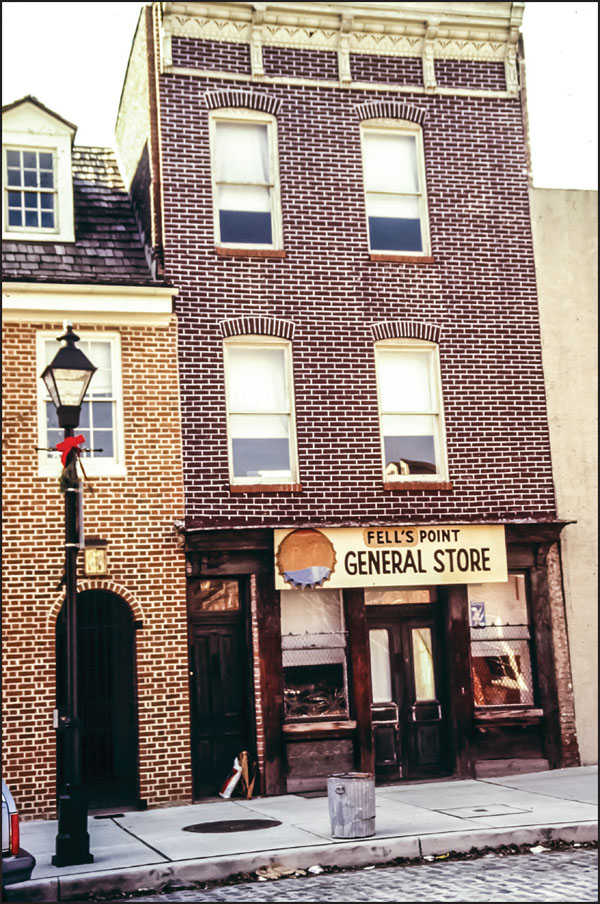

The community began to rebuild. H&S Bakery filled the air with pleasant smells of cinnamon bread. Small businesses multiplied. Their owners lived above their shops or nearby. The Fell’s Point General Store building in this 1993 photograph became home to the Black Olive Restaurant at 184 S. Bond Street; the restaurant’s owners live just down the street. (Courtesy of Ruth Gaphardt.)

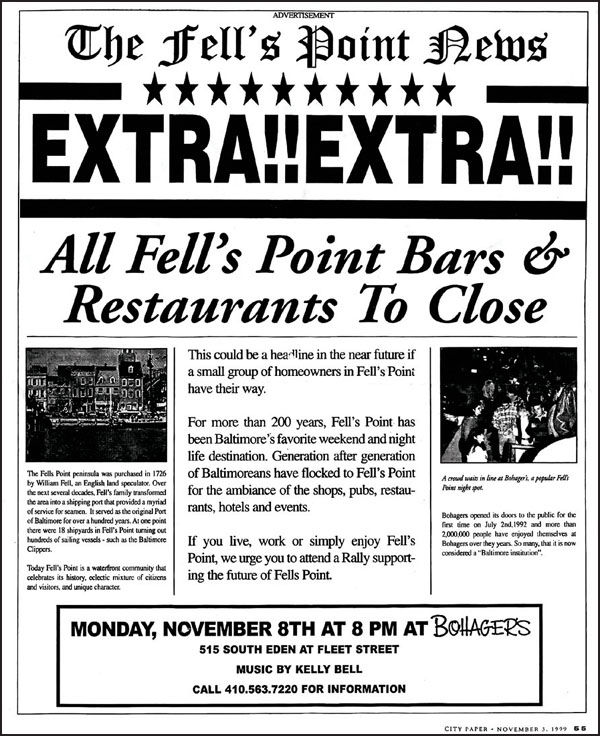

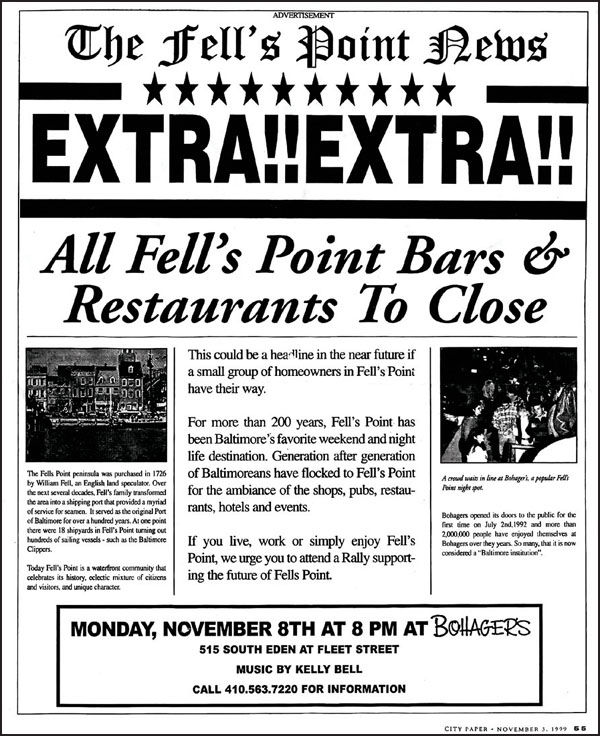

Old wharves were torn down or reopened as small mixed-business zones. Warehouses became offices. The Belgian block streets, some of which had been paved over, returned. But all was not peace and harmony. Preservationists still had to fight to maintain neighborhood history. Businesses quarreled with residents, as illustrated by this 1999 City Paper

ad. Bar owners wanted to expand. Homeowners wanted them to turn down the music.

The newest wave of immigrants are Latino, settling in Upper Fell’s Point. Empty buildings along Eastern Avenue now house tortillerias

and mercados

. In 1999, the Latin Palace opened at 509 South Broadway, known for its ornate facade and salsa dancing. The building was formerly the Broadway Theater (1916–1977), one of Fell’s Points largest movie theaters. Here, crowds linger at outside tables at the 2003 Fell’s Point Fun Festival.

Next to the Broadway Theater was Hecht’s Reliable Store. Established in 1857 by Samuel Hecht, Hecht’s originally sold used furniture, expanded to clothing, and eventually grew to 81 department stores in the Mid-Atlantic. The Broadway store closed in 1958. The last resident of the building was a Save-A-Lot. In 2010, Fell’s Point’s first and last department store burned down under suspicious circumstances. (Courtesy of Billy Collucci.)

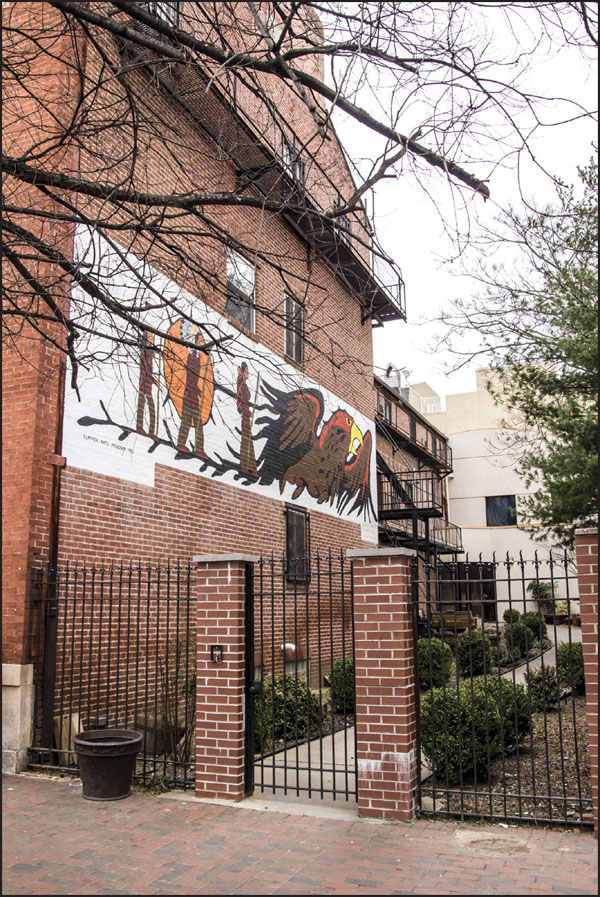

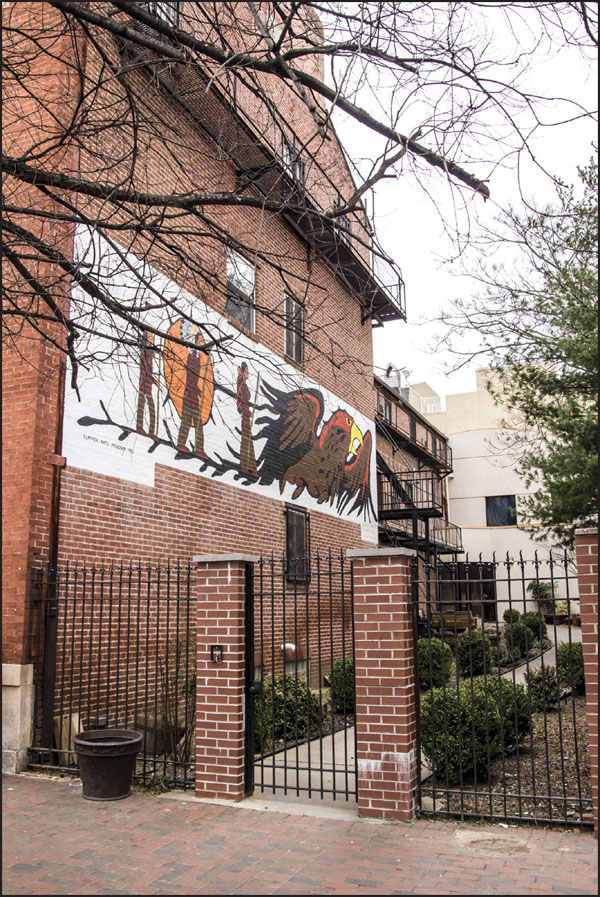

Native Americans in the area date back at least 12,000 years. The Baltimore American Indian Center, 113 South Broadway, was established in 1968 to serve the growing Lumbee community who migrated here from the South in the mid-20th century, along with Cherokees, African Americans, and white Appalachians. The mural on the side of the building was originally made by American Indian high school students and has recently been restored.

Fell’s Point’s past is still evident everywhere, but it has merged with the sights and sounds of modern life. Instead of the smell of guano and sound of hammering at Brown’s Wharf, one can hear cocktails being shaken and smell chocolate melting. Johns Hopkins offices now dominate the complex. Street-level storefronts house local shops, including Ten Thousand Villages, aMuse Toys, Kilwins Chocolates & Ice Cream, Fell’s Point Surf, Leadbetter’s Tavern, and Brassworks Co.

Across the street, one can stop in for a bite at the Points South Latin Kitchen, right next to the Admiral Fell Inn, and then browse some unique items for the body and home at Zelda Zen’s and grab a drink at the Horse You Came in On Saloon. For an opportunity to show Baltimore pride, Natty Boh Gear is just down the street. From there, one can get lost in the Sound Garden.

The Sound Garden began on the Brown’s Wharf side of Thames Street in 1993. It quickly grew and moved to the current 2,500-square-foot warehouse in 1995. Rolling Stone

magazine named it one of the 25 best record stores in the United States because of its amazing selection of used and new CDs, DVDs, LPs, video games, and Blu-rays. The store is known for hosting live concerts in its tiny space, causing lines to form for blocks.

Instead of train cars carrying chromium down Thames Street, today, tourists ask “Why are there tracks in the street?” Arguments roar in meetings with developers about the lack of parking and traffic congestion. Big business is moving in, but small businesses still stubbornly struggle on. An example is Killer Trash at 602 South Broadway. Elaine Ferrara opened the store in about 1979 and named it after her dog Killer and John Waters’s early 1970s store Divine Trash. It was one of the few stores open on the block for nearly two decades until the Marketplace at Fells Point finally finished development.

On the east side of the Point is “Belt’s Wharf,” a former warehouse at 949 Fell Street between Henderson’s Wharf and the Crescent. Belt’s Corporation was founded there in 1845. Before its 1980 makeover into offices, all the windows were barred. The cellar is rumored to have been used for cells to hold freed slaves captured by traders and shipped south for resale into slavery. Belt’s still owns the building but now leases it to Vaccinogen, an international cancer immunotherapy company.

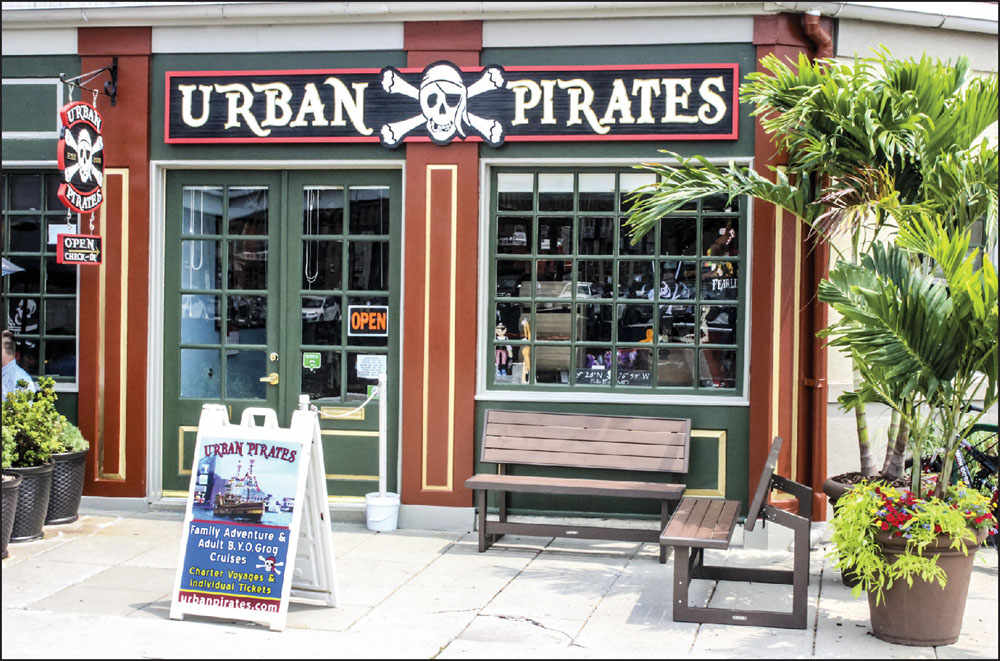

A short stroll away is Ann Street Pier, where one can get custom framing at the Frame House, have a choice of sandwiches at Pintango Bakery Cafe, wine at V-NO Wine Bar, or sushi at Nanami Cafe. After eating, perhaps it is time to take the family to Urban Pirates.

Sailing the waters of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor since 2008, Urban Pirates is owned and operated by Cara Joyce, who was determined to bring local families and tourists an amazing swashbuckling adventure. Inspired by her children’s love for all things pirate and her love of gatherings with good mateys, she and her crew created a unique and engaging experience fit for buccaneers of all ages. Urban Pirates prides itself on being involved in the community, donating their talents to local organizations and events. (Both, courtesy of Urban Pirates.)

Broadway Pier and the Square to the north continue to be the heart of Fell’s Point activities. On any given day at the pier, it is common to meet artists, musicians, performers, joggers, dog walkers, and tourists waiting in line for the water taxi. Along the pier, visitors may see simple pleasure boats, tugs, kayaks, sailing ships, and even massive military vessels.

In the evening, Broadway Square comes to life and dances to a different beat. The Pretzel Twist lights up as the sun goes down and the bars fill with thirsty visitors. Music drifts along the Belgian block streets and out over the water. Laughter, ghost stories, and clinking glasses create the symphony of a night in Fell’s Point. (Courtesy of Steven Dembo.)