4

Barn Owl Toddler: Love Me, Love My Owl

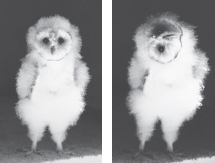

About two months old and curious about the camera. Wendy Francisco.

I COMMUTED TO work every day and brought Wesley with me. It was sometimes difficult to do my job while carrying him around, so one day I tried leaving him with one of the researchers.

“Hey Jergen, would you babysit my owl for a while?”

Jergen looked into the box, saw the sleeping white ball, and said, “Sure thing, yah!”

Wes was sound asleep when I left him, and I rushed through my work hoping he’d sleep long enough for me to get a lot done. But minutes later, I heard boots clumping across the big wooden floor in the owl barn and there was Jergen looking even paler than usual with a bright red blotch on each cheek.

“You’ve got to get back up to the office,” he panted.

“What’s wrong?” I cried, dropping everything. “Is he hurt?”

“I don’t know, I don’t know, just go up,” he said.

With my heart thundering in my chest I raced back up to the offices, taking the stairs two at a time. As I got to the third floor I could hear a horrible commotion of screeches. I ran into the room, and there was Wesley’s little white head bobbing up and down over the top of his nesting box. He was screaming so loudly that he had cleared out the room.

When I got to his box he just lowered his eyelids in greeting and gave a soft, sweet little twitter. All was well with the world now that I was with him again.

“You can’t leave him up here anymore,” Jergen said. “We’ll never get anything done.”

In the wild, there is no such thing as a babysitter. It’s the Way of the Owl.

After this scare, I took Wesley absolutely everywhere with me and did not leave him alone again until he was three months old, at which age he would have been starting to leave the nest. But until that time, I carried him in his box into every room as I worked. He stayed in his box by my side while I was feeding other animals and caring for them and whenever I was in the lab working with microscopes and other instruments.

LIFE WAS MUCH easier at home because I could give almost all my time and attention to Wesley. And Wesley observed me carefully. Normally he would have taken all of his cues from his mother. Now he was taking all of his cues from me. So when he saw me petting Courtney, Wendy’s golden retriever, Wesley was unafraid and curious. Being a baby meant he didn’t yet know his wildness and was open to making friends with any animal that came along. If his mother thought someone was okay, so did he. Courtney had been curious about Wesley for quite a while, so I decided to let them meet. Wendy supervised Courtney, and I held Wesley. They touched nose to beak and neither of them reacted. I set Wes on the ground and Courtney sniffed him over, then lay down next to Wesley as if he were her puppy. From then on, Wes felt right at home sitting between her front paws, and they would just hang out together.

With Courtney the dog. Stacey O’Brien.

Whenever I took care of Wendy’s daughter, Annie, who was born shortly after Wesley came home with me, I’d always involve Wesley, too. I could also leave Wesley in his nesting box next to my pillow in the bedroom, where he was used to sleeping, while I ate dinner with Wendy and her family. But the first three months seemed much longer than they really were because toting a fragile baby owl around was complicated and inconvenient.

One night when I was home with Wes, who was about a month old, the phone rang. I answered, and a soft, low voice said, “Hello, Stacey?” I went weak in the knees. The guy I had hoped for and schemed over, prayed for and cried over, Paul, was asking me out on a date. He was gorgeous, a musician, blond like me, short like me, into music like me. I had been pretty sure for a long time that Paul would make the perfect husband—it was just a matter of him realizing it. Did I mention he was gorgeous?

“I would love to,” I sputtered.

But then with a shock I remembered the Way of the Owl—and the “no babysitter” rule. I would have to bring Wesley with me. I could just imagine what would happen if he started screaming in a fancy restaurant. I had to say something so I blurted out, “Um, I’m raising a baby owl and I can’t leave him. Can I bring him with me in his little nest box with his little bowl of food? He eats mice, uh, but it’s okay because they’re already cut up.” I was dying a thousand deaths. He hesitated for a moment then said, “Sure, no problem.” We set up a date for two weeks later and hung up. I was thrilled.

Wesley was growing quickly. As he grew, he became more active, all legs and talons, pulling himself out of his blankets and trying to climb all over me. One night, as I was feeding him his cut-up mice, he suddenly lurched to his feet for the first time. He was six weeks old; he seemed surprised to be so tall and looked to me for an explanation. “Wesley! You’re standing up all by yourself!” I told him. He seemed reassured.

Wesley at five weeks old, with Stacey. Wendy Francisco.

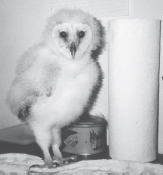

At about seven weeks, standing next to a standard paper towel roll so you can see how big he is. Stacey O’Brien.

Shortly afterward, Wesley took his first step—and with that step everything changed. He was like a human toddler, bounding around getting into everything in the bedroom. How was I going to protect an owl toddler? Fortunately, Caltech had loaned me a perch designed specifically for owls at this transitional stage. It was essentially a low mock tree stump nailed firmly to a 4-by-4-foot platform that sat on the floor. Wesley would be tethered to the stump with a leg jess. Next to his new perching post, I set his old nest box on its side, where he continued to sleep and groom himself.

Now that Wesley was mobile, I needed to introduce him to the leg jess and figure out how to leash him to the perching post, since I couldn’t corral him twenty-four hours a day. Most falconers put a leather jess on both legs of their bird, which they attach to a leash whenever taking the raptor outside. I modified this design and put a very soft leather jess on only one ankle—so Wesley would get the idea but wouldn’t have his legs tied together when on his leash. The leash was attached to the top of the perch-stump. He seemed to enjoy the new setup and the freedom it gave him to jump down and walk around on the floor. I leashed him whenever I couldn’t be there to supervise him, as he didn’t know what was dangerous and what was okay to play on, and I didn’t know what kind of trouble he could get into without my watching him. At this age, the babies would still be with their parents in the wild, learning to do what their parents did. They would be climbing out of the nest and sitting on tree branches, but still very dependent on Mom and Dad for guidance and food.

Once Wesley could walk confidently, he waddled behind me from room to room. Off his leash, he followed me everywhere and watched everything I did. And everywhere he went, he hurried. He’d put his wings up as if flying, although it looked as if he were playing “airplane.” He would bring each foot way up to his chest, then shoot that foot out as far as it would go, throwing his weight forward onto it, while pulling the other foot all the way up to his chest to do the same. The result was a hilarious galumphing gait that he kept for the rest of his life. The sincerity in his face made the whole thing seem even more ridiculous, and the sight of him rushing along like this would make Wendy and me giggle.

Even adult owls look funny when they run on the ground. Barn owls don’t usually walk on the ground in the wild, as they are only there long enough to grab their prey, so their feet are specialized for holding on to a branch with the long talons curled below. On the ground, the claws push their long toes up in an awkward way, and the extra pads on their feet seem to interfere with walking easily on flat surfaces. They don’t do a sophisticated little run like shorebirds or hop sensibly along the ground like sparrows. Barn owls tend to make a dramatic mess of it. This fits their personalities. Nothing is simple or straightforward. It’s got to be complicated, messy, urgent, and goofy-looking, in spite of the fact that owls take themselves very seriously.

On the morning that Wesley followed me from the bedroom into the living room for the first time, I sat down on the carpet and he scrambled to the safety of my lap, overwhelmed by this big new room. But in minutes curiosity overtook him, and he hopped down and began to explore. Wendy ran to get the camera. When she zoomed in on his face, Wesley stopped, cocked his head heavily to one side and regarded the camera with open curiosity. Wendy snapped photo after photo. Wesley stared right into the lens with his head bobbing up and down, back and forth, turning one way and then the other, the perfect high-fashion owl model. Wendy and I laughed so hard, it’s a wonder any of those photos were in focus.

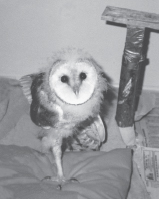

Almost three months old, using adolescent, or toddler, perch. Stacey O’Brien.

Despite his rapid growth, at five weeks Wesley still didn’t look like an owl. White down covered his entire body, including his wing stubs and legs. He looked misshapen and sort of lumpy. Around his bottom and hips there was a funny-looking mass of poofy white down feathers that he would retain into adulthood. I called these his “bloomers,” which is what they looked like. Owl bloomers have an important purpose in the wild. Their ultra softness efficiently traps the warm air against the body, providing extra warmth and fluff when the owl pulls his foot up to sleep during cold weather.

At six weeks, Wesley’s large head still overwhelmed his little body. His feet looked entirely reptilian and scaly. And they were huge compared to the rest of him, with talons sharp as razors. At this stage in the wild, baby barn owls flap their growing wings hard and climb tree trunks by hooking their talons into the bark and powering with leg and wing muscles straight up the side. It’s a great preflight exercise. Unfortunately, Wesley saw me as his personal tree. His beak and talons, meant to kill and rip flesh, really hurt. I started wearing thick jeans at all times, even to bed.

At my mother’s house one day, she watched Wesley climbing all over my bare arms.

“Don’t his tentacles hurt your skin, dear?” she asked.

“They’re not tentacles, Mom,” I informed her.

“Oh, I mean, don’t his testicles hurt your skin?”

“I think you mean talons, Mom. They’re called talons.”

She shook her head and questioned how I’d ever find a husband with bird scratches all over me. This comment stirred unease about my upcoming date with Paul. While biologists are proud of their scars and love to trade what’s-the-weirdest-thing-you’ve-been-bitten-by stories, Paul was a nonbiologist.

My arms were covered with long razor-thin scratches from Wesley’s talons, but I also had some unique marks from other animals, including gouges from large owls at Caltech. But my coolest scar by far was on my right wrist from a three-foot-long benthic worm with a six-inch retractable jaw. (Likely the inspiration for the jaw that shot out from the monster’s throat in the film Alien. It looks exactly the same.) Benthic is the term for the layer of sediment at the bottom of the ocean, where these worms live. Their jaws shoot up from the mud and snag prey as it scuttles above them. I was on a seagoing vessel studying the effects of the changing currents on benthic life (and also, concurrently, the zooplankton that floats on the ocean’s surface). We had netted a benthic worm that suddenly clamped on to my wrist and wouldn’t let go. I wanted to jump around the boat and scream, “Get it off! Get it off!” but with all those scientists around, that would have been so uncool. So I froze and choked out, “Can somebody help me detach this thing?” Finally we were able to pry the jaws open and throw it back into the sea, but it took a chunk of my flesh with it. Nonetheless, I was triumphant. I now had the best “bitten by” story of all.

Yet I wondered whether a benthic worm scar would be an asset on a date with a musician.

Wesley and I were developing a nighttime ritual. As I washed my face and brushed my teeth in the bathroom, Wesley stood on the counter. He watched while I turned on the faucet, ran the toothbrush under the water, and brought it to my mouth. It wasn’t long before he participated in the routine by grabbing the toothbrush and then parading around the sink with it in his beak. I would take the handle and gently try to pull it out of his mouth, resulting in a slow tug-of-war with me saying, “Wesley, give it back. It’s mine, Wesley, now, give it back,” to which Wesley responded by pushing his heels forward and pulling with all his might, screeching all the while until I would have to give in. “Okay, you win” and I’d carefully relinquish my grip. Finally, I figured out that all I had to do was take one of “his” and pretend to use it, let him grab it, then use a new one in peace. The moment he won this pitched battle, he’d lose interest in the toothbrush and throw it over the side of the counter, watching it fall with the kind of fascination babies in high chairs display after throwing their sippy cups.

One night Wesley poked his head under the running water. The feel of it surprised him and he jerked back, shook his head, and stared up at me as if asking, “What just happened?” Then he tried it again. Wesley had discovered water. He loved it. In fact, he became obsessed with water, trying to jump into the sink whenever I turned on the faucet. So I found an old dog dish, filled it up for him, and set it on the counter. From then on, Wesley imitated my bedtime routine using his own “sink,” swishing his face in the water while I was washing mine, and drinking while I brushed my teeth. This was surprising behavior, because it was well known that owls did not go near water, let alone wash their faces and drink. At that time, as far as we knew, no naturalist had ever reported observing an owl showing any interest in water, ever. Owls get all the fluids they need from eating mice. Wesley had not read the literature, however, and his doggie dish was a fixture in our lives from then on. The group at Caltech wanted to see this behavior for themselves, so I brought his doggie dish to work and they all watched him play, drink, and splash around in the water.

Wesley had begun to display a fascinating variety of facial expressions and body movements. They seemed to reveal a great complexity of thought and awareness. I talked to Wesley the same way Wendy talked to her infant daughter, Annie, using words and body language simply and consistently. I was reasonably certain that he would learn to understand me on some level, but had no idea to what degree. I’d use the same words for specific actions, like “Wesley, do you want some mice?” whenever he ate, or “Wesley, go to sleep,” when I went to bed. And whenever he saw something he thought looked interesting, which was nearly everything, I would name it out loud. Then he’d race toward the object in his galumphing gait, wings out like an airplane, with me running behind saying, “Wait! Not for owls, not for owls!”

THE NIGHT OF the big date finally arrived. I stood at Paul’s front porch with the little third wheel asleep in a box tucked under my scratched arms. Paul opened his front door with a smile, ushered us in, and then peered down at Wesley.

“That’s an owl?”

Wesley was just waking up from his nap.

“Well, yes, it’s a baby owl,” I said.

Paul bent his head over the box for a second look.

“And are those…” he exclaimed with widening eyes, “…cut-up mice??”

“It’s what he eats,” I offered.

Paul turned pale and backed away.

“That is gross. That is really gross.”

There was no going out to a restaurant. Paul ordered in a pizza and ate it perched tensely on the armchair away from the couch where I sat with Wesley. He nervously eyed the box as if Wesley or the cut-up mice were going to come flying out and attach themselves to his head. My visions of going down the aisle to “She Blinded Me with Science” faded quickly. I found myself wishing we were back at home, just Wesley and me, getting ready for bed.

Finally, Paul popped in a video and settled back in his chair. Oh, good, he’s finally relaxing, I thought. Then I heard snoring. And it wasn’t Wesley. Mom had been right. I hate admitting that.

I slipped out of Paul’s house with Wesley, strapped his box into the passenger seat with the seat belt, and started the car. A blanket of sadness descended. I knew Paul would never call again. I’d been so sure he was “the one.” What a bummer. Oh well, maybe there was something to be said for having Wesley as sort of a litmus test for guys. Love me, love my owl, I thought. I certainly couldn’t be with a guy who didn’t have some interest in animals. Paul seemed to have none. Wesley’s eyes searched my face as if trying to decipher a work of art. Perhaps my little owlet had just prevented me from making a big mistake.

I pulled into the long circular driveway at Wendy’s house. As I walked up the driveway, her flock of geese announced my arrival. The horses nickered, and a goat bleated. I could hear the chickens cackling to each other. The scent of hay was on the breeze.

It was a relief to be home with Wes.

We got ready for bed and had our nightly cuddle. Wesley lay on his tummy across my left arm, nestled against my stomach, head in my hand with his legs hanging over the side of my arm. With my right hand I rubbed him on the bridge of his nose, which I knew he loved, because he closed the disks of his face like a little taco over each eye, opening up the area over his nose for rubbing. With his “cuddle face,” he fluffed the feathers immediately around his nose, so that most of his beak was hidden and all I could see was a little bit of the pink tip.

One of my tears hit the feathers on his back. “I’m all right, Wes.” I told him, “I wouldn’t be happy with a man who doesn’t understand animals anyway.”

Actually, Paul did call a few times over the next year or so. He’d always eventually ask, “Do you still have that owl?” He said “owl” as if he were asking, “Do you still have that human head hidden under the bed?” or something equally horrible. “Oh, yes!” I’d say and describe Wesley’s antics to him. He’d sigh deeply and ask, “How long do they live in captivity?” I’d always answer, “Fifteen years or more.” Then he’d say “Okay,” and quickly end the conversation.

A few years later he got married.