6

Attack Kitten on Wings

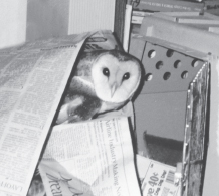

Wesley at about a year old, “killing” a film canister. Stacey O’Brien.

MY BEDROOM AT Wendy’s was dimly lit, but otherwise looked pretty much like any other bedroom full of stuffed animals. One particular day, however, one of the seemingly stuffed animals had a menacing glint in its eyes. It was Wesley and he was crouching motionless, his attention fixed on a small object in front of him. Suddenly, his head started gyrating wildly from side to side, round and round and upside down. In an instant, he shot into the air and pounced on his newfound prey—a hair scrunchee—with all his wild might. He pounced again and again, flying into the air and slamming back onto it with clenched talons, killing it over and over again.

Finally satisfied that the hair scrunchee was thoroughly dead, he turned to the next victim, an unfortunate empty film canister. Wesley flew around the room to gain speed and hit the canister at full power. Wham. Wesley pounced again. Whack. He held down the canister with his talons and gave it a bite that would have severed its spine, if it had had one. Then he looked at me for the first time and let out his new victory cry—“Deedle deedle deedle DEET DEET DEET DEET deedle deedle dee!” I murmured approval and he took a victory lap. Soon he would be ready for his first live mouse.

OWLS HAVE NO pack, flock, or herd, so they are absolute loners except for their mate and offspring. Because of this inborn inclination, Wesley was strengthening his bond with me and had started to consider every other life form an enemy combatant. If anyone else even looked into the room, he had recently begun to exhibit a strange display, which I called his “owl no-nos,” because it looked as if he were shaking his head no.

My first experience with owl no-nos occurred in the wild owl section at Caltech, when I came upon a fledgling barn owl standing on the floor of an aviary, hunched over as if injured, rubbing his beak on the ground. I immediately went to his rescue, but he did not respond. If anything, the beak rubbing became even more pronounced. Maybe he was choking. I got down on my hands and knees and put my face close to his to figure out what was wrong. I stayed in that position for quite a while and he never changed his behavior or acknowledged my presence. I thought he must really be in trouble and ran up to Dr. Penfield’s office, gasping that we had an owl down.

“Stay calm,” he said, “and describe the exact behavior to me.”

“Oh, Dr. Penfield, he’s all hunched over and his beak is almost touching the floor and he’s rocking his head back and forth exactly as if he’s saying ‘No, no, no.’ I went in and checked—”

“You went in?”

“Yes and I got down on the floor with him to see what’s wrong and put my face right up to his beak and couldn’t see anything—”

“You what?” He leapt up from his chair. “That’s the last threat before ripping your face off, didn’t you know that? Stacey, you are lucky to have your eyes. That owl was trying to tell you that he was going to try to kill you.”

I suddenly felt weak all over. What a close call.

“Well, that seems like a stupid threat display,” I mumbled, embarrassed at my ignorance. “The owl can’t even see the object of his concern, so how could he be threatening it? And who on earth could possibly interpret anything that ridiculous-looking to be a threat?”

Dr. Penfield just blinked.

It’s not clear if other animals recognize this behavior as a threat. To say the least, it’s downright strange, which might be enough to scare off another animal; but perhaps it’s understood only among owls. It seems to be specific to barn owls, a signature move of theirs, though all owls rotate their wings forward to make themselves look larger, puff their feathers up, and sway from side to side, swinging their heads back and forth as they look at their enemy, and hiss and clack their beaks. All this occurs before barn owls go into the no-nos, which is their final warning. They look a lot like the monster in the Alien movies when it would hunch itself and sway menacingly. Hissing seems to be a universally understood threat among all animals, and most animals puff themselves up in some manner when threatened. Think of swans and cats, who puff up and hiss. But the fact that barn owls don’t make eye contact during the actual no-nos makes it seem a ridiculous threat display until you realize that their primary source of information comes from their ears. They are more likely to respond to the sound of an enemy tensing its muscles and shifting to pounce than they are to rely on visual cues like we would. It’s very difficult for us to think the way a barn owl does, so his ways can seem pretty ridiculous—but they make sense to him, which is all that matters.

NOW THAT WESLEY was more mature and tended to clam up with anyone else, I was the only one who could watch his playful antics. I tried to describe his entertaining flying and daredevil maneuvers to my friends, but they didn’t quite believe me. One friend, Kurt, begged me to find a way to hide him so that he could see Wesley play. I finally gave in to his pleas, figuring that if I were to carefully ensconce Kurt in my bed under lots of blankets and he were to keep perfectly still, just like a field biologist observing wild animals from a blind, then we could bring Wesley into the room and Kurt could watch him do his thing. Kurt agreed to my brilliant plan, saying, “If it works with me, then you can do this for anyone else who wants to see him play.”

I put Wesley in the bathroom by himself while Kurt quietly sneaked into my bedroom. We piled blankets on top of him and fashioned a little peephole.

“Okay,” I said, “whatever you do, don’t move or make any sounds. And remember, patience is the key! He will start to play and if you can’t see something, don’t move, just wait until he comes back into view, okay?”

A huge Norwegian guy from South Dakota who could carry a refrigerator down a flight of stairs all by himself, Kurt suddenly looked worried.

“What do I do if something happens?” he asked.

“What could happen?” I said impatiently. “I’ll come back in about twenty minutes. If he isn’t playing, we’ll try again another time.”

Once Kurt was comfortable I said, “Okay, now be completely silent. I’m going to go get him.”

“Okay,” he whispered.

I placed Wesley inside the door of my bedroom and closed it like I always did when I let him fly around and play by himself. I didn’t stay in the room because I thought that if he noticed someone breathing under the covers, he would think it was me, hopefully forgetting that I had left the room. I wandered off into the house and hung out with Wendy and Annie for a while, losing track of the time, so it was more like forty-five minutes later when I decided to check on how things were going. I stood at the door hoping to hear the sounds of Wes playing. I didn’t hear a thing. It was dead silent.

I opened the door to see Wesley standing on the bed with his face less than an inch from the peephole, his body crouched, wings flung all the way out and rotated forward in the classic owl threat posture. He was rocking from side to side doing his no-nos, and occasionally lunging with a loud hissing snap of his beak.

From under the covers I heard a tiny voice, “Help me…”

“What are you doing, Wesley?” I said, and picked him up and leashed him to his perch. Kurt then threw the covers back. He was sweating and pale, almost green.

“Where were you?” he demanded.

“Uh…well, I just thought you’d be okay. When did he discover you?”

“When? When? The second you shut the door, that’s when! He came straight at me and has been threatening my eye for the last two hours!”

“Kurt,” I said, “It’s only been about forty-five minutes.”

“Forty-five minutes? You try having an owl snapping at your eye for forty-five minutes sometime!”

I held back my laughter. “I’m sorry, Kurt. I was sure it would work out. At least we tried.”

I should have known that Wesley would figure out that the person under my blankets wasn’t me. I had underestimated his intelligence by a long shot. After all, if owls can hear a mouse’s heartbeat, Wesley could have heard the heart of a big guy like Kurt and recognized it as different from my own.

Kurt made a long circle around Wesley’s perch on his way back to the door and scooted out as Wes flung himself forward at him with one last snap of his beak.

BECAUSE WESLEY’S FLYING had improved, he needed an adult perch. I bought a parrot perch and modified it so that it was about four and a half feet tall, with a wooden dowel across the top for Wesley to stand on and a round platform below about three feet in diameter. In the center of the dowel I added a leather attachment for his leash, which turned freely so that nothing would get tangled, and I used strips of leather and chicken wire to block the area below the dowel so that Wesley wouldn’t wind his leash around it and get pinned. I covered the platform with towels and taped them into place. The nesting box was history now. Wesley developed an entirely new play routine on his perch.

About eight years old on his adult perch, Wesley enjoys a mouse dinner, preparing to swallow it headfirst. Stacey O’Brien.

Late one night, 3:00 a.m. to be exact, I should have been sleeping, but Wesley was up and it was far more entertaining to watch him play. He knew the exact limits of his leash and flew in a circle just within that perimeter, playing “helicopter,” then flinging himself at the perch, power punching it by throwing his legs forward in an arc so that all the muscles of his chest, legs, and feet were fully engaged when he hit the dowel. Pow! What a move! I had added that resounding smack to my subconscious list of sounds that meant all was well in our world. Then he jumped off the dowel and onto the platform, with a hollow pom!

Then quite deliberately he dived over the side of the platform and hung there dangling on his jess like a huge golden bat. Enjoying the view upside down, he looked over the room from that perspective. The first time he did this I had tried to help him right himself, but he was so irritated that I did not intervene again. Once he tired of this view, he reached up, grabbed the towels with his talons, and powered himself back up onto the platform using his abdominal muscles, like a gymnast pulling himself up onto a bar. He would do this for the rest of his life just for fun, it seemed. I’d walk into a room and there he’d be, hanging upside down, looking around calmly. I sometimes did lift him back up to the perch just to make sure he was okay, which he always was. The only time I’ve known of an owl doing this in the wild was from a curious picture of a spotted owl hanging from a branch with the same expression of enjoyment that Wesley had. The person who took the picture said the owl wasn’t stuck and easily righted itself when it got tired of hanging that way. Ravens and crows do this also, seemingly for fun.

Television documentaries about animals all echo that they play in their youth because it’s necessary for them to learn the skills they need to survive—building muscle, coordination, fighting, and hunting moves. But this conventional wisdom doesn’t begin to explain the full picture. Some species never seem to play at all, yet they still survive in the wild. On Wendy’s little farm, we had chickens, geese, cockatiels, and a cockatoo, among other animals, and we observed them closely at every stage of life. Annie’s pet chicken Herkomer never appeared to play, although she was as tame as an animal could be. Other species of birds play all their lives, like birds of the parrot family—and owls—long after they’ve learned adult skills. Wendy once knew a woman who kept a screech owl that also played like a kitten with wings all of its life, well into old age.

I actually don’t think play is related only to predation, as prey animals such as rats, mice, ground squirrels, and goats play as adults, and some predators such as owls, otters, cats, and dogs also play as adults. At a wildlife refuge where I volunteered, grown Bengal tigers played for hours in their pool. One of them would carry his favorite red ball everywhere, throwing it ahead and pouncing on it, tossing it into the water then jumping in after it, pushing it all over the surface with his nose. Tiring of that, he’d take it out of the pool and roll on his back, batting the ball into the air like a kitten, using all four paws to keep it in place. His enclosure mates would join in the fun, rolling around and growling like Harley-Davidsons revving their engines.

So what makes one type of animal playful whereas another isn’t? Or are they all playful, but we are unable to recognize it when some species do play? Clearly it’s not simply that animals play just to learn certain skills. There needs to be more scientific study on why animals play or don’t play without the cultural bias that many western scientists seem to have against ascribing “fun” or “joy” to animals for fear of seeming to anthropomorphize them.

Wesley was as playful at age thirteen as he was when he was a year old. Of course, I could say that he learned a certain behavior in order to experience the infusion of endorphins that play released, but really, is this necessary? Maybe he just did it for fun. Where did our emotions come from if not from our animal ancestors? Many human emotions are similar to those of animals. We are them and they are us.

When off his leash and flying around the room, Wesley dive-bombed the pillows on my bed and popped straight back up, barely losing speed, then zoomed across the room to smack his talons full force into the couch, leaving punctures wherever he landed—an attack kitten. Then he headed straight for the wall and landed on the edge of a picture frame, holding on with all his might and flapping his wings so hard that the frame banged against the wall over and over again, leaving a dent. He finally lost his grip, rescued himself from falling with a quick flip sideways and a swoop to the floor. There he explored every nook and cranny, including suitcases, boxes, and bags. Galumphing with great intensity toward the dark closet—I had left the door open—he slipped inside.

For a long time I heard him rummaging around. Then nothing. Hmm, awfully quiet in there. I started to worry and finally crawled into the closet to investigate. There was Wesley holding perfectly still, doing a split, with one leg desperately clinging to the top of one dress, the other leg holding on to another. Wesley was stuck, and uncharacteristically quiet about it. I recalled that, in the wild, when animals think they’re in trouble, they immediately freeze, hoping not to attract predators. He may have been anxious in that relatively new territory, but he allowed me to rescue him and return him to his perch.

That wouldn’t be the last time Wesley decided to mountain climb the clothing in my closet. From his vantage point on the floor, looking up at the dark spaces between clothes, it probably felt familiar to his instincts, which had evolved so that he would expect to be inside a hollow tree, or be attracted to that vertical dark situation. He’d explore this “tree” by working his way to the top, bracing himself between my dresses as he ascended. His legs would inch apart a little more at each step until he could no longer move, then he’d hold on for dear life with his talons. Finding him in that helpless position, I’d give him a little nudge so he could finish climbing up.

Soon, every piece of fabric I owned bore little punctures, as if someone had patiently gone over each garment with an ice pick. I figured that being a biologist was explanation enough, so I just walked around in clothes with lots of holes in them. As a rule, scientists don’t seem interested in fashion and don’t tend to worry about what other people think, outside the machismo of the science culture. If I had taken a poll around Caltech, few would have known what Prada was, much less which shoes were worn in what season. If we shower and shave, we figure, what more do you want from us? One of my office mates owned ten identical pairs of gray pants, white shirts, and white socks, to go with one pair of Birkenstocks. For decades, he wore the same outfit to work and never needed to shop or make a decision about what to wear. His was a fairly typical and perfectly acceptable style among scientists.

Wesley left a mark on almost every item I owned, and I sacrificed more and more of my property to Wesley’s whims—clothes, books, papers, blankets, and furniture. I just didn’t care about those things and felt like the luckiest person in the world to have him in my life. Each talon puncture was evidence of my baby’s brilliance and personality. I actually saved books that he’d ripped apart because his beak marks were on them. I was pretty besotted.

Wesley’s play included me of course. Our early game of his chasing my feet under the blankets had evolved. At first he had just run back and forth on the bed chasing my toes, but as his flying improved, he would fly straight up into the air, flip, then do a power dive and thrust his legs forward for the attack. Then he would fly a lap around the room to gain speed and pounce with all his might on my well-blanketed feet.

Of course there were little mistakes. One time my foot slipped out from under the covers while I was napping, and he did his power dive into my bare foot with full talon crunch. I leapt straight up from my pillow shrieking in pain, scaring Wesley so much that he flew around the room in a panic until I calmed him down and was able to hold him. He started his “I’m so ashamed” routine of pushing me away, refusing to look at me, hunching up, and trying to face a wall. But I comforted him, crooning to him, “It’s okay, it’s okay.” While I cradled him, my foot was bleeding, but that would have to wait. It wasn’t his fault, I was the one who had let him play this way for so long.

Since owls don’t flock, herd, or pack, they have no social setup for correcting each other’s behavior. Therefore, Wesley had no way to interpret any act of aggression except as a threat on his life. For this reason, the number one rule in interacting with birds of prey is that you can never show them any aggression. You cannot try to discipline or correct them as you would a child or dog. They would not understand it. I could never raise my voice or do anything that might seem at all aggressive, even when trying to stop Wesley from doing something for his own protection. I could only gently remove him from whatever situation was putting him or me in danger. Eventually, he might learn that a certain behavior wasn’t allowed, but not in the usual way. It took longer and required much more patience than the normal pet owner or parent is accustomed to.

Wesley had his own mind and did not obey me, but rather, lived in a kind of mutual cooperation with me. I did not actually try to train him in the traditional sense, but simply endeavored to protect him from himself. He learned from me as he would have learned from an owl parent—not by being corrected, I think, but by observing me and making his own decisions about how to behave. Certainly I was not interested in changing him, since I was learning from him about what it meant to be an owl. Taming an animal is not the same as training him. I am not an animal trainer.

Social animals in general are easier to teach because they seem to think the same way we do; they understand that a show of aggression is just a temporary correcting reaction. Wolves growl and snap at pack members, saying, in effect, “Back off,” so that they avoid fighting and particularly avoid fighting to the death. They understand aggressive signals. Owls don’t. Owls will think you are trying to kill them, and for the rest of their lives they will remember that you tried to kill them. So if you mess up even once and yell at a bird of prey or, God forbid, make a threatening gesture toward it, it will never be as tame with you again. The owl has no context for such frightening behavior. That’s it. There are no second chances in the wild. That is the Way of the Owl.

One of the reasons I had moved in with Wendy was to help out with her baby, Annie, while her husband was on the road. It was a joy to be involved in helping to rear a child, since I did not have children of my own. Following Wendy’s lead, we never said Annie’s name in anger and we didn’t say “no” unless it was a very serious matter. We just informed Annie, “Not for babies” when she reached for something unsafe, and reserved the word no for the most dangerous situations.

Knowing that I had to be as careful with Wesley as with Annie, I tried Wendy’s strategy with him, too, and I avoided using the word no for minor issues. Whenever he got into something that wasn’t safe, I said, “Not for owls” and removed the object gently from his grasp. Because he tended to lock on to anything that interested him, I’d often have to distract him to get him to let go. Trying to get him to let go of a mouse, for instance, would have been almost impossible if I hadn’t distracted him, and he would have fought me for it. Thankfully, there were only a few occasions when I needed to take a mouse from him, for instance, when it wasn’t fit for him to eat.

Annie came to understand the seriousness of “no” and would stop dead in her tracks if one of us said it. Wesley, however, only stopped long enough to consider whether or not he thought it was worthy advice. Although he knew exactly what it meant, he was still an owl—stubborn and wild.

Most people prefer to work with animals that have a social instinct, because they are more malleable. Owls’ willfulness often causes them to be misunderstood. I was told that owls were “stupid,” but much later learned that the person who told me this really had meant you can’t train them to do your bidding. Well, those are two very different statements. Owls are highly intelligent. They just keep their own counsel and don’t care to obey anyone else. Why should they? In the wild they are loners, although to their mates they are the sweetest, most devoted creatures on earth.

During Wesley’s first year, I continued to follow him around as he played and explored, watching out for anything that could pose a threat. Danger lurked everywhere, and as his owl mother, I had the job of saving his life on a fairly continual basis. Besides “child-proofing” everything, I was extremely careful about what I allowed into the living space we shared. Drinking glasses and flower vases were forbidden because he might knock one over and cut himself. Besides the obvious poisons like drain cleaners and bleach, other dangerous liquids included all caffeinated beverages: the caffeine jolt we depend on in the morning can cause heart attacks in birds. I had no idea what might lurk in houseplants, so I just kept them out of the room. No plastic bags—Wesley might have put his head into one, gotten stuck, and suffocated. Eventually, almost all my framed pictures were taken down, as his flying attacks on the frames sometimes ended with his falling pretty hard to the ground with the picture. Anything on which he could land that would flip up in his face was also forbidden, such as a saucer or plate. Any important paper items were also eventually hidden in drawers so he wouldn’t rip them to shreds.

A few years old, playing in newspapers next to his emergency carrier. Stacey O’Brien.

Living in earthquake country meant I had to keep furniture bolted to the studs in the walls and had to make sure that nothing heavy that could fall on him was on a wall near Wesley’s perch. Earthquakes usually start small, so even a minor quake would set everyone into crisis mode. I kept an animal carrier under Wesley’s perch and would race to put him in there at the first sign of a temblor. He seemed to understand what was going on and stayed in the carrier quite happily until I felt that the danger had passed.

Before I knew it, Wesley was celebrating his first birthday, February 10. Dr. Penfield and I figured that he was four days old when I first saw him on Valentine’s Day, so I made the tenth his official birthday (or hatch day). I decided it was time to let him kill his own mouse in honor of all he’d learned and accomplished. After all, he’d been practicing his flying and pouncing moves, so why not try them out on the real thing? I did not take this lightly and stood by to intervene if Wesley started to hurt or scare the mouse without killing it instantly.

I got a small mouse and put it into the shower where it wouldn’t hop out. Wesley would be able to take his time and chase it down. I imagined he’d pop into the air, do a fast swoop with the talon-crunch follow-up, then bite the neck just as he had bitten the film canister. No such luck. Wesley was terrified of the live mouse, cowering against the shower door and hissing under his breath. Gathering his last bit of courage, he finally faced it and gave it his “no-nos,” standing in front of it and slowly moving his head from side to side. Not intimidated, the mouse simply washed its face. Dr. Penfield had said that an imprinted owl could never learn to hunt, so I should have expected this. The reasons for this belief are complicated. The most obvious is that an owl imprinted on a human doesn’t have parents to teach him, and he was imitating me. But his threatening of the mouse was interesting. Perhaps he was confused, since he was used to seeing dead mice. Seeing one alive and animated may have frightened him so that he reverted to a threat gesture. But there may have been a lot more to it than that.

Humans and other mammals sense danger using a very busy part of the brain called the amygdala, which handles sensory input. It acts as a sort of Grand Central Station for interpreting what the senses perceive, using memory and emotions in the process. In birds, the amygdala has developed to become much larger in proportion to that of mammals, and may partially account for the extreme intelligence of birds as well as some of the differences in their thinking. Scientists used to think birds’ brains were simpler than those of mammals; now we think they may be just as complex, but in a very different way.

Birds make the same kinds of neural connections as mammals, but certain parts of their brains have developed differently. In birds, the larger amygdala may have evolved to handle more complex processes than it does in mammals. In mammals, this structure is a primary player in the handling of emotion, but in birds it is used more to integrate information and less if at all for emotion and danger assessment.

The bottom line is that birds’ brains have evolved a different intelligence from our own and we are just now starting to get a handle on how they use their brains. By comparing the brain functions and structures of birds and mammals, we can now see that their brains evolved in different physiological directions. Even with different structures taking on different functions, however, the two groups developed similar kinds of intelligence—so similar, in fact, that we can communicate and share emotions with each other.

Whatever was causing Wesley’s strange response to the mouse, I decided to wait until next year to try it again.