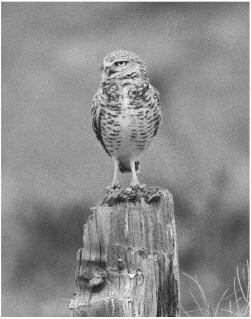

focus  Burrowing Owl

Burrowing Owl

The bird from which Burrowing Owl Estate Winery takes its name is an unusual owl in several ways—it is more diurnal than nocturnal and has long, bare legs and a habit of doing regular knee-bends. But what really sets the burrowing owl apart from its cousins is that it nests and roosts underground, in burrows dug by badgers or other fossorial mammals. Like many other small owls, burrowing owls eat a variety of prey; the local birds generally catch pocket mice in the spring and early summer, then switch to large insects such as beetles and Jerusalem crickets in summer and early autumn. By October the insect numbers dwindle and pocket mice begin to hibernate, so the owls migrate south, probably wintering in California and northern Mexico. They return in late March or early April, and the evening air echoes with the males’ cu-kooo calls.

Burrowing owls were once fairly common in the Okanagan and south Similkameen valleys, but they declined rapidly in the late 1800s when cattle overgrazed the area, degrading the habitat and likely trampling a lot of the nests in sandy soils. In the 1980s and 1990s, the British Columbia Ministry of Environment attempted to reintroduce these owls to the Okanagan, bringing owl families up from a healthy population in central Washington. Most were released in the grasslands adjacent to Burrowing Owl vineyards. Owl numbers were maintained as long as new recruits were brought in each year, but when imports from south of the border stopped in the early 1990s, the numbers declined quickly. The last burrowing owl was seen here in 1995, three years before the winery produced its first vintage.