focus  Kokanee

Kokanee

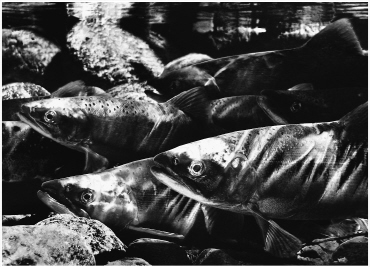

Kokanee are a type of sockeye salmon, and like their oceangoing cousins, they spend the first year of their lives in a lake, eating plankton. But kokanee stay in the lake for the rest of their lives, returning in their third or fourth year to the place where they were born to spawn and die. Some kokanee in Okanagan Lake spawn along gravelly shores, mostly across the lake from Peachland along the rocky headland of Okanagan Mountain Provincial Park. But most spawn in creeks up and down the valley. In 1966 fisheries biologists introduced mysid shrimp into Okanagan Lake, since they had noticed that mature kokanee in lakes with these large shrimp grew to record sizes. Unfortunately, they didn’t realize that the shrimp also compete with young kokanee for small plankton, and they effectively starved the small fish. In the early 1970s, kokanee numbers in Okanagan Lake began to plummet, going from over a million spawners to about ten thousand by 1998. The sportfishery was closed from 1995 to 2005, and a number of other conservation measures were put into place, including operating a shrimp trawler to reduce the mysid population. By 2007 the kokanee spawning population had rebounded to 296,000, and sportfishing has been reopened for short trial periods.