esed), the term connotes not only forgiveness but loyalty in keeping His covenant with Israel,8 in stark contrast with the inexcusable disloyalty of the people of Israel. Daniel thus began by assuring himself of God’s greatness and goodness.

esed), the term connotes not only forgiveness but loyalty in keeping His covenant with Israel,8 in stark contrast with the inexcusable disloyalty of the people of Israel. Daniel thus began by assuring himself of God’s greatness and goodness.The third vision of Daniel the prophet, following the preceding visions of chapters 7 and 8, concerns the program of God for Israel culminating in the coming of their Messiah to the earth to reign. Although other major prophets received detailed information concerning the nations and God’s program for salvation, Daniel alone was given the comprehensive program for both the Gentiles, as revealed to Daniel in preceding chapters, and for Israel, as recorded in Daniel 9:24–27. Because of the comprehensive and structural nature of Daniel’s prophecies, both for the Gentiles and for Israel, the study of Daniel, and especially this chapter, is the key to understanding the prophetic Scriptures. Of the four major programs revealed in the Bible—for the angels, the Gentiles, Israel, and the church—Daniel had the privilege of being the channel of revelation for the second and third of these programs in the Old Testament.

This chapter begins with Jeremiah’s prophecy of seventy years of the desolations of Jerusalem and is advanced by the intercessory prayer of Daniel. It concludes with Daniel’s third vision, given through the angel Gabriel, which provides one of the most important keys to understanding the Scriptures as a whole. In many respects, this is the high point of the book of Daniel. Although previously Gentile history and prophecy recorded in Daniel was related to the people of Israel, the ninth chapter specifically takes up prophecy as it applies to the chosen people.

9:1–2 In the first year of Darius the son of Ahasuerus, by descent a Mede, who was made king over the realm of the Chaldeans—in the first year of his reign, I, Daniel, perceived in the books the number of years that, according to the word of the LORD to Jeremiah the prophet, must pass before the end of the desolations of Jerusalem, namely, seventy years.

Daniel received this vision “in the first year of Darius,” which means the events of Belshazzar’s feast in chapter 5 occurred between the visions of chapters 8 and 9. It is not clear where chapter 6 fits into this order of events, but it also may well have occurred in the first year of Darius’s reign, either immediately before or immediately after the events of chapter 9. If Daniel’s experience at Belshazzar’s feast as well as his deliverance from the lions had already been experienced, these significant evidences of the sovereignty and power of God may well have constituted a divine preparation for the tremendous revelation now about to unfold.

The immediate occasion of this chapter, however, was Daniel’s discovery in the prophecy of Jeremiah that the desolations of Jerusalem would be fulfilled in seventy years. In addition to his oral prophetic announcements, Jeremiah had written his prophecies in the closing days of Jerusalem before its destruction by the Babylonians. In 597 B.C. Jeremiah had even written a letter to the exiles in Babylon (Jer. 29) in which he had announced that their time in captivity would last seventy years (v. 10). Jeremiah himself had been taken captive by Jews rebelling against Nebuchadnezzar and had been carried off to Egypt against his will to be buried in a strange land in a nameless grave. But the timeless Scriptures that he wrote found their way across desert and mountain to faraway Babylon and fell into the hands of Daniel. How long Daniel had been in possession of these prophecies is not known, but the implication is that Daniel had now come to fully comprehend Jeremiah’s prediction and realized that the seventy years prophesied had about run their course. The time of the vision recorded in Daniel 9 was 538 B.C., about 67 years after Jerusalem had first been captured and Daniel carried off to Babylon (605 B.C.).

Jeremiah had prophesied, “This whole land shall become a ruin and a waste, and these nations shall serve the king of Babylon seventy years. Then after seventy years are completed, I will punish the king of Babylon and that nation, the land of the Chaldeans, for their iniquity, declares the LORD, making the land an everlasting waste” (Jer. 25:11–12). Later, Jeremiah added in his letter to the exiles: “For thus says the LORD: When seventy years are completed for Babylon, I will visit you, and I will fulfill to you my promise and bring you back to this place. For I know the plans I have for you, declares the LORD, plans for wholeness and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope. Then you will call upon me and come and pray to me, and I will hear you. You will seek me and find me. When you seek me with all your heart, I will be found by you, declares the LORD, and I will restore your fortunes and gather you from all the nations and all the places where I have driven you, declares the LORD, and I will bring you back to the place from which I sent you into exile” (29:10–14).

On the basis of these remarkable prophecies, Daniel was encouraged to pray for the restoration of Jerusalem and the regathering of the people of Israel. Daniel was probably too Old and infirm to return to Jerusalem himself, but he had lived long enough to see the first expedition of pilgrims return. This occurred in “the first year of Cyrus king of Persia” (Ezra 1:1), and Daniel lived at least until “the third year of Cyrus king of Persia” (Dan. 10:1) and possibly some years longer.

Darius was either another name for Cyrus, or had been appointed by Cyrus as king of Babylon (see the earlier discussion of chapter 6). The assertion of Daniel 9:1 that Darius “was made king” indicates that he was invested with the kingship by some higher authority. This could well agree with the supposition that he was installed as viceroy in Babylonia by Cyrus the Great.1 This appointment is confirmed by the verb “was made king,” which does not seem a proper reference to Cyrus himself. It is of interest that in the Behistun inscription, Darius I (not the Darius described in Daniel 9) refers to his father, Hystaspes, as having been made king in a similar way.

Anderson distinguishes the duration of the captivity from the duration of the desolations of Jerusalem in Daniel 9:2. He states, “The failure to distinguish between the several judgments of the Servitude, the Captivity and the Desolations, is a fruitful source of error in the study of Daniel and the historical books of Scripture.”2

Anderson goes on to explain that Israel’s servitude and captivity began much earlier than the destruction of the temple. Although Anderson’s dates are not according to current archeological findings (606 B.C. instead of 605 for the captivity, 589 B.C. instead of 586 for the desolation of the temple, and his date for the decree of Cyrus, 536 B.C. instead of 538), his approach to the fulfillment of Jeremiah’s prophecy is worthy of consideration. As discussed in the exposition of chapter 1, the captivity probably began in the fall of 605 B.C. at which time a few, such as Daniel and his companions and others of the royal children, were carried off to Babylon as hostages. The major deportation did not take place until about seven years later. According to Wiseman, the exact date of the first major deportation was March 16, 597 B.C., after the fall of Jerusalem following a brief revolt against Babylonian rule. About 60,000 were carried away at that time.3

Jerusalem itself was finally destroyed in 586 B.C.,4 and this, according to Anderson, began the desolations of Jerusalem, the specific prophecy of Jeremiah 25:11, also mentioned in 2 Chronicles 36:21 and in Daniel 9:2.

Jeremiah 25:11–12 predicts that the king of Babylon would be punished at the end of seventy years. Jeremiah 29:10 predicts the return to the land after seventy years. For these reasons, it is doubtful whether Anderson’s evaluation of Daniel 9:2 as referring to the destruction of the temple itself is valid. The judgment on Babylon and the return to the land took place about twenty years before the temple itself was rebuilt and was approximately seventy years after captivity beginning in 605 B.C. Probably the best interpretation, accordingly, is to consider the expression “the desolations of Jerusalem” in Daniel 9:2 as referring to the period 605 B.C. to 539 B.C., and the date of 538 B.C. for the return to the land.

This definition is supported by the word for “desolations,” ḥorbôt, which is plural, apparently including the environs of Jerusalem. The same expression is translated “all her waste places” in Isaiah 51:3 (cf. 52:9). Actually the destruction of territory formerly under Jerusalem’s control even predated the 605 date for Jerusalem’s fall. And as Hoehner notes, “The reason for Israel’s captivity was their refusal to obey the Word of the Lord from the prophets (Jer. 29:17–19) and to give their land sabbatical rests (2 Chron. 36:21). God had stated that Israel, because of her disobedience, would be removed from her land and scattered among the Gentiles until the land had enjoyed its Sabbaths (Lev. 26:33–35).”5 So the length of time for the captivity related to the land as much as it did to the city or the temple.

Although it is preferred to consider Daniel 9:2 as the period 605–539 B.C., Anderson may be right in distinguishing the period of Israel’s captivity from that of Jerusalem’s desolation. Zechariah 1:12 refers to God’s destruction of the cities of Judah for seventy years, which may extend to the time when the temple was rebuilt. This is brought out in Zechariah 1:16: “Therefore, thus says the LORD, I have returned to Jerusalem with mercy; my house shall be built in it, declares the LORD of hosts, and the measuring line shall be stretched out over Jerusalem.” It is most significant that the return took place approximately seventy years after Jerusalem’s capture in 605 B.C., and the restoration of the temple (515 B.C.) took place approximately seventy years after its destruction (586 B.C.), the latter period being about twenty years later than the former. In both cases, however, the fulfillment does not have the meticulous accuracy of falling on the very day, as Anderson attempts to prove. It seems to be an approximate number as one would expect by a round number of seventy. Hence, the period between 605 B.C. and 538 B.C. would be approximately sixty-seven years; and the rededication of the temple in March of 515 B.C. would be less than seventy-one years from the destruction of the temple in August of 586 B.C.

What is intended, accordingly, in the statement in Daniel 9:2 is that Daniel realized that the time was approaching when the children of Israel could return. The seventy years of the captivity were about ended. Once the children of Israel were back in the land, they were providentially hindered in fulfilling the rebuilding of the temple until seventy years after the destruction of the temple had also elapsed.

Several principles emerge from Daniel’s reference to Jeremiah’s prophecy. First, Daniel took the seventy years literally and believed that there would be a literal fulfillment. Even though Daniel was fully acquainted with the symbolic form of revelation that God sometimes used to portray panoramic prophetic events, his interpretation of Jeremiah was literal and he expected God to fulfill His Word.

Second, Daniel realized that the Word of God would be fulfilled only on the basis of prayer, which led to his fervent plea recorded in this chapter. On the one hand, Daniel recognized the certainty of divine purposes and the sovereignty of God that would surely fulfill the prophetic word. On the other hand, he recognized human agency, the necessity of faith and prayer, and the urgency to respond with human action as it relates to the divine program. His custom of praying three times a day with his windows open to Jerusalem revealed his own heart for the things of God and his concern for the holy city.

Third, Daniel recognized the need for confession of sin and national repentance as a prelude to restoration (Deut. 30:1–3; Jer. 29:10–14). With this rich background of the prophetic program revealed through Jeremiah, Daniel’s own prayer life, and his concern for Jerusalem as the religious center of Israel, Daniel expressed his confession and intercession to God on behalf of his fellow exiles.

Because Daniel, for the first time, used the word “LORD” or Jehovah in Daniel 9:2, repeating the expression in verses 4, 10, 13, 14, and 20, some critics have used this as an argument against the authenticity of this passage and the prayer that follows.6 However, it seems perfectly natural for Daniel to use the personal covenantal name of God in a context where he is interceding on behalf of his people to the God “who keeps covenant and steadfast love with those who love him and keep his commandments” (v. 4). Daniel’s entire prayer is based on Israel’s covenant relationship to God, so his use of God’s personal name, which He revealed to Israel, is both appropriate and expected.

9:3–4 Then I turned my face to the Lord God, seeking him by prayer and pleas for mercy with fasting and sackcloth and ashes. I prayed to the LORD my God and made confession, saying, “O Lord, the great and awesome God, who keeps covenant and steadfast love with those who love him and keep his commandments.”

Daniel’s prayer is a beautiful example of obedience. After announcing the curses of the covenant, with the final curse resulting in exile (Deut. 28), God promised to restore the people if they would repent (Deut. 30:1–5). Daniel prayed on behalf of all the Jewish exiles, acknowledging God’s righteous judgment because of the nation’s sin and asking God to restore the city of Jerusalem, the temple, and the people in exile.

Encouraged by knowing of God’s intention to restore Jerusalem, Daniel sought to make adequate preparation to present his confessions and petitions to the Lord. Every possible element of preparation was included. First, he turned his face “to the LORD God,” meaning that he turned away from other things to concentrate on his prayer. This implies faith, devotion, and worship. Daniel’s activity in prayer had a specific end expressed by the word “seeking,” which anticipated his hope to find ground for an answer to his prayers.

Daniel’s attitude of mind and steadfastness of purpose was supplemented by prayer and supplications, that is, prayer in general and petition specifically. This was accompanied by every known auxiliary aid to prayer: namely, fasting, that he might not be diverted from prayer by food; sackcloth, a putting aside of ordinary garments in favor of rough cloth speaking of abject need; and ashes, the traditional symbol of grief and humility.7 In a word, Daniel left nothing undone that might possibly make his prayer more effective or more persuasive.

While God honors the briefest of prayers, as Nehemiah 2:4 indicates, effective prayer requires faith in His Word, proper attitude of mind and heart, privacy, and unhurried confession and petition. Daniel’s humility, reverence, and earnestness are the hallmarks of effective prayer. Daniel began his prayer by stating his reliance on the fact that the majesty of God’s person and the greatness of His power are manifested especially in His fulfilling His covenant promises and showing mercy to those who love Him and keep His commandments. As Glueck has brought out in his study of the term “steadfast love” ( esed), the term connotes not only forgiveness but loyalty in keeping His covenant with Israel,8 in stark contrast with the inexcusable disloyalty of the people of Israel. Daniel thus began by assuring himself of God’s greatness and goodness.

esed), the term connotes not only forgiveness but loyalty in keeping His covenant with Israel,8 in stark contrast with the inexcusable disloyalty of the people of Israel. Daniel thus began by assuring himself of God’s greatness and goodness.

9:5–6 “We have sinned and done wrong and acted wickedly and rebelled, turning aside from your commandments and rules. We have not listened to your servants the prophets, who spoke in your name to our kings, our princes, and our fathers, and to all the people of the land.”

Here began Daniel’s prayer of confession. He himself is one of the few major characters of the Old Testament to whom some sin is not ascribed, though we know theologically he was not sinless. In the context of his prayer he was dealing not with his personal sins, but was identifying with Israel’s sin and the collective responsibility he shared both in God’s promises of blessing and warnings of divine judgment. Daniel did not spare himself or his people in his confession. Calvin points out a fourfold description of the extent of their sin: first, they “have sinned” (Heb.  ), meaning a serious crime or offense; second, they had “done wrong”; third, they had “acted wickedly,” or “conducted themselves wickedly”; and fourth, by sinning in this way, they had “rebelled, turning aside from your commandments and rules,” that is, “become rebellious and declined from the statutes and commandments of God.”9 Stuart notes, “The climactic construction of the sentence is palpable. To turn back from obedience to the divine statutes, in the frame of mind which belongs to rebels, is the consummation of wickedness, and so Daniel rightly considers it. The variety of verbs employed here, indicates the design of the speaker to confess all sin of every kind in its full extent”10 (italics in original).

), meaning a serious crime or offense; second, they had “done wrong”; third, they had “acted wickedly,” or “conducted themselves wickedly”; and fourth, by sinning in this way, they had “rebelled, turning aside from your commandments and rules,” that is, “become rebellious and declined from the statutes and commandments of God.”9 Stuart notes, “The climactic construction of the sentence is palpable. To turn back from obedience to the divine statutes, in the frame of mind which belongs to rebels, is the consummation of wickedness, and so Daniel rightly considers it. The variety of verbs employed here, indicates the design of the speaker to confess all sin of every kind in its full extent”10 (italics in original).

The heinousness of Israel’s sin is amplified in verse 6 by the fact that they disregarded the prophets God sent to them. As Wood writes, “Not only had the Law not been obeyed, but the people had not listened to God’s prophets, who had called this disobedience to their attention.”11 This disobedience to the prophets characterized all classes of Israel, from her kings to “all the people.” Even in such times of revival as the reign of Hezekiah, when the king’s messengers went throughout the land calling people to the Passover at Jerusalem, many of the people “laughed them to scorn and mocked them” (2 Chron. 30:10). Israel’s departure from the precepts and judgments of God’s Word, as well as the disregard of the prophets, “is the beginning of all moral disorders,” as Leupold expresses it.12

9:7–9 “To you, O Lord, belongs righteousness, butto us open shame, as at this day, to the men of Judah, to the inhabitants of Jerusalem, and to all Israel, those who are near and those who are far away, in all the lands to which you have driven them, because of the treachery that they have committed against you. To us, O Lord, belongs open shame, to our kings, to our princes, and to our fathers, because we have sinned against you. To the Lord our God belong mercy and forgiveness, for we have rebelled against him.”

In verses 7–8, Daniel contrasted God’s righteousness with the confusion that belonged to Israel. God had been righteous in His judgments upon Israel, and in no way did Israel’s distress reflect upon the attributes of God adversely. By contrast, Israel’s shame of face that had made them the object of scorn of the nations was their just desert for rebellion against God. Daniel itemized those who were especially concerned: first, the kingdom of Judah that was carried into captivity by the Babylonians, and second, “all Israel, those who are near and those who are far away,” that is, the ten tribes of the kingdom of Israel that were carried off by the Assyrians in 721 B.C. The scattering of the children of Israel to “all the lands to which you have driven them” was not occasioned by one sin, but by generation after generation of failure to obey the Law or to give heed to the prophets.

Tatford summarizes Daniel 9:5–8 in these words:

There was no tautology in the prolific accumulation of expressions he used: it was rather that he sought to express by every possible word the enormity of the guilt and contumacy of himself and his people. They had sinned in wandering from the right, they had dealt perversely in their willful impiety, they had done wickedly in their sheer infidelity, they had rebelled in deliberate refractoriness, they had turned aside from the Divine commandments and ordinances. Their cup of iniquity was full. Their guilt was accentuated by the fact that prophets had been sent to them with the Divine message and they had refused to listen. All were implicated—rulers, leaders (the term “fathers” being used, of course, in a metaphorical rather than in a literal sense), and the people. God was perfectly just, but a shameful countenance betrayed their own guilt. Nor was the confusion of face limited to Judah and Jerusalem: it was true of all Israelites throughout the world. Indeed, their scattering was in punishment for their own unfaithfulness to God. Daniel associated himself completely with his people in acknowledging their wrong-doing and freely confessed that their shamefacedness was due to perfectly justified corrections: they had sinned against God.13

In verse 9, Daniel contrasted the mercy and forgiveness of God with Israel’s sin. The righteous God is also a God of mercy. It is on this ground that Daniel was basing his petition. In doing so, he turned from addressing God directly in the second person to speaking of God in the third person, as if to state a truth for all who would hear, a theological fact now being introduced as the basis for the remainder of the prayer.

9:10–14 “[We] have not obeyed the voice of the LORD our God by walking in his laws, which he set before us by his servants the prophets. All Israel has transgressed your law and turned aside, refusing to obey your voice. And the curse and oath that are written in the Law of Moses the servant of God have been poured out upon us, because we have sinned against him. He has confirmed his words, which he spoke against us and against our rulers who ruled us, by bringing upon us a great calamity. For under the whole heaven there has not been done anything like what has been done against Jerusalem. As it is written in the Law of Moses, all this calamity has come upon us; yet we have not entreated the favor of the LORD our God, turning from our iniquities and gaining insight by your truth. Therefore the LORD has kept ready the calamity and has brought it upon us, for the LORD our God is righteous in all the works that he has done, and we have not obeyed his voice.”

With God’s mercy and forgiveness as a backdrop, Daniel plunged into a recital of the extent of Israel’s sin in verses 10–11. Again, he restated that Israel had not obeyed the voice of God. They had not walked according to His laws as proclaimed to them by the Lord’s servants, the prophets. The word translated “laws” in verse 10 means literally “instructions” (cf. Isa. 1:10ff.). The rebellion was not on the part of a few, but “all Israel has transgressed your law and turned aside.” Because of their persistent failure and rebellion against God, the prophesied curse pronounced upon Israel as “written in the Law of Moses the servant of God” was applied, referring specifically to the covenant curses announced in Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28.

In Deuteronomy 28, for example, the conditions of blessing and cursing are set forth before Israel in detail. If they obeyed, they would have every blessing, temporal and spiritual, from God. If they disobeyed, God would destroy them and scatter them over the earth. Moses had made perfectly clear that Israel’s situation would indeed be desperate if they disobeyed the Lord. Most of Deuteronomy 28 is devoted to itemizing these curses, concluding with the prophetic warning of Israel’s expulsion from the land (Deut. 28:63–67) and the resultant uncertainty of life and future that would characterize individual Israelites. It was these passages and warnings of God to which Daniel referred.

Mendenhall has shown that the Mosaic covenant has a close parallel to certain suzerainty treaties (i.e., treaties between a Great King and his vassals) of the Hittite Empire. Sanctions are typically supplied in these treaties by a series of blessings and cursings as also illustrated in Leviticus 26:14–39 and Deuteronomy 27. Such warnings are witnessed by heaven and earth (cf. Deut. 4:26 and Isa. 1:2) and in their form are similar to many passages in the Old Testament.14

In verses 12–14, Daniel itemized the evil which God had brought upon the people of Israel as a result of their sin. By this judgment God had “confirmed his words, which he spoke against us and against our rulers who ruled us, by bringing upon us a great calamity” (cf. Isa. 1:10–31; Micah 3). The climax of God’s judgment was the destruction He brought “against Jerusalem,” which was the final blow to Israel’s pride and security.

Adding to all their earlier sins, Israel did not turn to the Lord in prayer. Even in the midst of the terrible manifestation of God’s righteous judgment, there was no revival, no turning to Him; rulers and people alike persisted in their evil ways. Daniel was saying that God had no alternative but to judge, even though He was a God of mercy, for when mercy is spurned, judgment is inevitable. Daniel’s conclusion in verse 14 brought out this fact. Porteous notes that the words “kept ready” or “vigilant” are the same words Jeremiah used when he told how God was watchful over His Word to perform it (Jer. 1:12; cf. 31:28; 44:27). God was faithfully keeping His Word both in blessing and in cursing, which must have encouraged Daniel in anticipating the end of the captivity.15

9:15–19 “And now, O Lord our God, who brought your people out of the land of Egypt with a mighty hand, and have made a name for yourself, as at this day, we have sinned, we have done wickedly. O Lord, according to all your righteous acts, let your anger and your wrath turn away from your city Jerusalem, your holy hill, because for our sins, and for the iniquities of our fathers, Jerusalem and your people have become a byword among all who are around us. Now therefore, O our God, listen to the prayer of your servant and to his pleas for mercy, and for your own sake, O Lord, make your face to shine upon your sanctuary, which is desolate. O my God, incline your ear and hear. Open your eyes and see our desolations, and the city that is called by your name. For we do not present our pleas before you because of our righteousness, but because of your great mercy. O Lord, hear; O Lord, forgive. O Lord, pay attention and act. Delay not, for your own sake, O my God, because your city and your people are called by your name.”

Daniel laid a solid groundwork for his prayer by his confession of sin and acknowledgment of God’s righteousness and mercy. Beginning in verse 15, Daniel turned to the burden of his prayer—that God would act righteously and in mercy to forgive and restore the people of Israel. Daniel appealed first to the power and forgiveness God manifested in delivering His people from Egypt. In doing so, God had “made a name” for Himself among the nations. The deliverance of Israel from Egypt is, in many respects, the standard Old Testament illustration of God’s power and ability to deliver His people. In the New Testament, the resurrection of Jesus Christ is God’s standard of power (Eph. 1:19–20). In Christ’s future millennial reign, the standard of power will be the regathering of Israel and their restoration to the land (Jer. 16:14–15).

The three dispersions of Israel from the land and their regathering are among the more important demonstrations of God’s power. He had allowed them to go into Egypt and then delivered them in the Exodus. He had punished them by the captivities, but now Daniel was pleading with Him to restore His people to their land and their city. The future and final regathering of Israel in relation to the millennial kingdom will be the final act, fulfilling Amos 9:11–15, when Israel will be regathered never to be dispersed again. In both the dispersions and the regatherings, God’s righteousness, power, and mercies are evident. The thought of God’s deliverance of Israel from Egypt overwhelmed Daniel with the thought of the nation’s sinfulness that seemed to block the way for restoration. “We have sinned, we have done wickedly” was the theme of Daniel’s prayer to this point. But he went on to petition for Israel’s forgiveness and restoration.

Interestingly, in verses 15–19, Daniel addressed God only as Adonai and Elohim and no longer used His covenant name, Yahweh, as he did in verses 4–14. Most commentators have ignored this significant change in address.16 Montgomery goes so far as to insert the word Yahweh in his translation, although he calls attention in his critical apparatus to the actual Hebrew.17 The explanation seems to be that in using the word Adonai, Daniel was recognizing God’s absolute sovereignty over him as Lord.

Daniel significantly appealed again to God’s righteousness in verse 16. Daniel recognized that Israel’s restoration depended on God’s mercy, yet he also acknowledged that it must be “according to all your righteous acts.” Here is implied the whole system of reconciliation to God by sacrifice, supremely fulfilled in Jesus Christ. Daniel understood that there is no contradiction between the righteousness of God and His mercy and forgiveness. The same Scriptures that predict God’s judgment upon Israel also predict its restoration. It would be in accordance with the veracity of God as a covenant-keeping God not only to inflict judgment, but to bring in the promised restoration.

Daniel’s appeal for restoration was grounded in the fact that Israel was God’s people, and that Jerusalem was God’s city. His focus in these verses is on “Jerusalem and your people” (v. 16) especially because “your city and your people are called by your name” (v. 19). Israel’s restoration would also be a testimony to the nations before whom she was currently “a byword.” “The prayer is a tragic confession of guilt. Jerusalem should have been the mount unto which all nations would flow, and Israel should have been a light unto the Gentiles, but because of the people’s sins, Jerusalem and Israel had become a reproach.”18

In verse 17, Daniel added one additional request to his prayer. The sanctuary itself, the place where God met man in sacrifice, was in desolation and the whole sacrificial system had fallen into disuse because of the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple. Ultimately, it was not simply the restoration of Israel that Daniel sought, nor the restoration of Jerusalem or even of the temple, but specifically the sanctuary with its altar of sacrifice and its holy of holies.

The eloquence of Daniel’s prayer reached its crescendo in verses 18–19. How it must have delighted God to hear His devoted servant present his petitions. How it must have moved God’s heart to hear Daniel plea for Him to listen to Daniel’s prayer and see the plight of Israel. If prayer can be called persuasive, Daniel’s prayer certainly merits this description. Daniel’s holy life, careful preparation in approaching God, uncompromising confession of sin, and appeal to God’s holy character illustrate the kind of prayer that God delights to answer. Led by the Spirit of God, Daniel had expressed precisely the prayer that God wanted to hear and answer.

Although no other portion of the Bible breathes with more pure devotion or has greater spiritual content than Daniel’s prayer, it has been attacked without mercy by the higher critics. Acting on the premise that the book of Daniel is a second-century forgery and not written by Daniel the prophet in the sixth century B.C., the critics take exception to this section as a particular proof that the book of Daniel as a whole could not have been written by Daniel.

Montgomery has summarized the objections of the critics. Although making preliminary concessions that the prayer “is a liturgical gem in form and expression, and excels in literary character the more verbose types found in Ezr. and Neh.,” he holds that “the prayer is of the liturgical type which existed since the Deuteronomic age represented by Solomon’s Prayer, 1 Ki. 8, the prayers of Jer., Jer. 26.32.44, and the prayers in Ezr.–Neh., Ezr. 9, Neh. 1.9.” Montgomery goes on to say, “By far the largest part of this prayer consists of language found in those other compositions.”19

Not all the higher critics, however, accept the explanation that Daniel 9:2–19 is an interpolation not originally in the book. Montgomery has summarized the complicated arguments both for and against this view:

Von Gall, Einheitlichkeit, 123–126, has developed the thesis that Dan.’s prayer is an interpolation, although the rest of his work contends for the practical integrity of the canonical books. He is followed by Mar., Cha. [Marti’s Commentary, and Charles]. It is patent, as these scholars argue, that the theme of the prayer does not correspond to the context, which would seem to require a prayer for illumination, cf. 2:20 ff., and not a liturgical confession bearing on the national catastrophe. Further, Dan.’s prayer for immediate redemption is in contrast to the recognition of the far distance of that event, 8:26 and end of this chap. It is pointed out that 5:4a repeats 5:3 and especially that 5:20 is a joint with the main narrative, which is resumed in 5:21; this would explain the repetition: “while I was speaking and praying and confessing” “while I was speaking in prayer.” The present writer agrees with Kamp. [Kamphausen] in finding these arguments inconclusive. The second-century author may well have himself inserted such a prayer in his book for the encouragement of the faithful, even as the calculation of the times was intended for their heartening…. For an elaborate study of the Prayer, defending its authenticity and also arguing for its dependence on the Chronicler, S. Bayer, Daniel-studien, Part 1.20

The critics’ argument is based on the false premise that Jeremiah’s seventy years and the seventy weeks of Daniel 9:24–27 are the same. Because Daniel distinguishes these two periods, it is argued that the material is an interpolation. But it is the critics who are wrong, not Daniel. The alleged copying from a common source on the part of Daniel, Nehemiah, and Baruch is better explained by the fact that Daniel was written first (sixth century B.C.) and that Nehemiah and Baruch had Daniel before them. Again, it is the critics’ theories that are the basis of their argument, and the theories are in error. Daniel’s critics argue in a circle. Assuming a second-century date for Daniel, they then criticize the book for not harmonizing with their erroneous premises. However, the unity and beauty of this passage are its own defense.

9:20–23 While I was speaking and praying, confessing my sin and the sin of my people Israel, and presenting my plea before the LORD my God for the holy hill of my God, while I was speaking in prayer, the man Gabriel, whom I had seen in the vision at the first, came to me in swift flight at the time of the evening sacrifice. He made me understand, speaking with me and saying, “O Daniel, I have now come out to give you insight and understanding. At the beginning of your pleas for mercy a word went out, and I have come to tell it to you, for you are greatly loved. Therefore consider the word and understand the vision.”

The answer to Daniel’s prayer was already on its way even while he was still making it. Verse 20 implies that the angel Gabriel was sent at the very beginning of his prayer. According to verse 21, Gabriel came about the time of the evening sacrifice. It is obvious that the prayer recorded here is only a summary of the actual prayer, which probably was lengthy and culminated at the time of the evening sacrifice.

The reference to “the man Gabriel” is not a denial that he is an angel, but serves to identify him with the vision of Daniel 8:15–16. The term man (Heb. ’ish) is also used in the sense of a servant.21 And, as Wood notes, it is possible that ’ish was used because “he appeared in human form….”22 As brought out in chapter 8, there is an interesting play upon the thought here. Leupold notes: “The term ‘Gabriel’ means ‘man of God,’ but with this difference: the first root, gebher, means ‘man’ as the strong one, and the second root, ’el, means the ‘Strong God.’”23 In other words, this expression could be translated “the servant, the strong one of the strong God.” Daniel identified Gabriel as the one he had seen in his earlier vision in chapter 8. Gabriel, according to Daniel, “came to me in swift flight,” and arrived at the time of the evening sacrifice. The Hebrew for “came … In swift flight” is difficult. The thought is that God directed Gabriel to go immediately to Daniel at the beginning of his petition.

It is a touching observation that Gabriel arrived at the time of the evening sacrifice. There had been no evening sacrifice for half a century since the destruction of the temple in 586 B.C.; but in Daniel’s youth, he had seen the smoke rise from the temple into the afternoon sky with its reminder that God accepts a sinful people on the basis of a sacrifice offered on their behalf. This sacrifice usually began about 3 P.M., and consisted of a perfect yearling lamb offered as a whole burnt offering accompanied by meal and drink offerings. All of this typified the future sacrifice of Jesus Christ upon the cross as the spotless Lamb of God (Heb. 9:14). As the evening sacrifice was also a stated time for prayer, Daniel was encouraged to pray. Just as God in a sense met the spiritual need of His people at the time of the sacrifice, so Gabriel was sent by God to meet Daniel’s special need at this time and to remind him of God’s mercy.

Gabriel stated that the purpose of his coming was to give Daniel “insight and understanding” (v. 22). Daniel’s prayer was not specifically directed to his own need of understanding God’s dealings with Israel, but this was the underlying assumption of his entire prayer. God wanted to assure Daniel of His unswerving purpose to fulfill all His commitments to Israel, including their ultimate restoration. The commandment to Gabriel to go apparently came from God Himself, although conceivably he might have been sent by Michael the Archangel. Because of the magnitude of the revelation that follows, however, it is better to ascribe it to God Himself. Gabriel had come to show Daniel what was necessary to understand the entire matter of Israel’s program, and specifically, to consider the vision of the seventy weeks described in the verses that follow. Gabriel also spoke of Daniel’s special relationship to the Lord as one who was “greatly loved.” In many spiritual and moral characteristics Daniel was like the apostle John, the disciple whom Jesus loved (John 13:23). The long preamble of twenty-three verses leading up to the great revelation of the seventy weeks is, in itself, a testimony to the importance of this revelation. The stage is now set for Gabriel to reveal to Daniel God’s purposes for Israel, culminating in Christ’s second coming to establish His kingdom on the earth.

9:24 “Seventy weeks are decreed about your people and your holy city, to finish the transgression, to put an end to sin, and to atone for iniquity, to bring in everlasting righteousness, to seal both vision and prophet, and to anoint a most holy place.”

The concluding four verses of Daniel 9 contain one of the most important prophecies of the Old Testament. Although many divergent interpretations have been advanced to explain this prophecy, they may first be divided into two major divisions, namely, the Christological and the non-Christo-logical views.

The non-Christological approach may be subdivided into the liberal critical view and the conservative amillennial view. Liberal critics, assuming that Daniel is a forgery, find in this chapter that the pseudo-Daniel confused the seventy years of Israel’s captivity with the seventy weeks of Gabriel’s vision. As Montgomery summarizes the matter in the introduction to chapter 9, “Dan., having learned from the Sacred Books of Jer.’s prophecy of the doom of seventy years’ desolation for the Holy City, a term that was now naturally drawing to an end (1.2), sets himself to pray for the forgiveness of his people’s sin and the promised deliverance (3–19). The angel Gabriel appears to him (20–21), and interprets the years as year-weeks, with detail of the distant future and of the crowning epoch of the divine purpose (22–27).”24 For Montgomery, this is not prophecy at all but merely presented by the pseudo-Daniel as if it were. Whatever fulfillment there is, it is a fulfillment in history largely accomplished in the life and persecutions of Antiochus Epiphanes.25 In his summary, Montgomery states,

The history of the exegesis of the 70 Weeks is the Dismal Swamp of O. T. criticism. The difficulties that beset any “rationalistic” treatment of the figures are great enough, but the critics on this side of the fence do not agree among themselves; but the trackless wilderness of assumptions and theories and efforts to obtain an exact chronology fitting into the history of Salvation, after these 2,000 years of infinitely varied interpretations, would seem to preclude any use of the 70 Weeks for the determination of a definite prophetic chronology. As we have seen, the early Jewish and Christian exegesis came to interpret that datum eschatologically and found it fulfilled in the fall of Jerusalem; only slowly did the theme of prophecy of the Advent of Christ impress itself upon the Church, along with the survival, however, of other earlier themes. The early Church rested no claims upon the alleged prophecy, but rather remarkably ignored it in a theological atmosphere surcharged with Messianism. The great Catholic chronographers naturally attacked the subject with scientific zeal, but their efforts as well as those of all subsequent chronographers (including the great Scalinger and Sir Isaac Newton) have failed.26

In other words, Montgomery, for all of his scholarship and knowledge of the history of interpretation, ends up with no reasonable interpretation at all.

Goldingay takes a slightly different approach, but arrives at essentially the same conclusion. “A fundamental objection to such attempts either to vindicate or to fault Daniel’s figures is that both are mistaken in interpreting the 490 years as offering chronological information. It is not chronology but chronography: a stylized scheme of history used to interpret historical data rather than arising from them….”27 In essence he seems to argue that no precise historical fulfillment can be found because one was never intended. But such a view ignores precise historical markers at the beginning of the chapter (vv. 1–2) as well as Gabriel’s announcement that what follows was God’s answer to Daniel’s prayer, designed to give Daniel “insight and understanding.” The vision must relate to Daniel’s prayer for the ultimate restoration of the Jewish people, the city of Jerusalem, and the temple.

Some conservative scholars have done no better, however, as illustrated by Young. He treats the Scriptures with reverence, but finds no satisfactory conclusion for the seventy weeks of the prophecy and leaves it more or less like Montgomery, without a satisfactory explanation.28

The conservative interpretation of Daniel 9:24–27 usually regards the time units as years. “Weeks” is literally “sevens,” and can refer to a week of days (i.e., 7 days, Gen. 29:27) or to a week of years (Lev. 25:8). The decision is, however, by no means unanimous. Some amillenarians, like Young, who have trouble fitting this into their system of eschatology, consider this an indefinite period of time and leave the issue somewhat open. Further, as Young points out, the word sevens is in the masculine plural instead of the usual feminine plural. No clear explanation is given except that Young feels “it was for the deliberate purpose of calling attention to the fact that the word sevens is employed in an unusual sense.”29

Most commentators agree that the time unit is not days. Further, the fact that there were seventy years of captivity, discussed earlier in the chapter, would seem to imply that years were also here in view.30 The interpretation of years is at least preferable to days, as Young comments: “The brief period of 490 days would not serve to meet the needs of the prophecy, upon any view. Hence, as far as the present writer knows, this view is almost universally rejected.”31

Leupold, also an amillenarian, says: “Since the week of creation, ‘seven’ has always been the mark of divine work in the symbolism of numbers. ‘Seventy’ contains seven multiplied by ten, which, being a round number, signifies perfection, completion. Therefore, ‘seventy heptads’—7 × 7 × 10—is the period in which the divine work of greatest moment is brought to perfection. There is nothing fantastic or unusual about this to the interpreter who has seen how frequently the symbolism of numbers plays a significant part in the Scriptures.”32 In view of the precision of the seventy years of the captivity, however, the context indicates the probability of a more literal intention in the revelation.

The conclusion of orthodox Jewry, obviously non-Christological, is that the seventy weeks of Daniel 9 end with the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70. This, of course, also does not give an adequate explanation of the text.

The overwhelming consensus of scholarship, however, agrees that the time unit should be considered years. It is normal for lexicographical authorities in the field of Hebrew to define the time unit as “period of seven (days, years),” and “heptad, weeks.”33 The English word “weeks” here is misleading, since the Hebrew is actually the plural of the word for seven without specifying whether it is days, months, or years. The only system of interpretation, however, that gives any literal meaning to this prophecy is to regard the time units as prophetic years of 360 days each, according to the Jewish custom of having years of 360 days with an occasional extra month inserted to correct the calendar as needed. The seventy times seven is, therefore, 490 years beginning with “the word to restore and to build Jerusalem” (v. 25) and culminating 490 years later. (A full discussion can be found in an excursis at the end of the chapter.)

In view of the great variety of opinions that find no Christological fulfillment at all in this passage, the interpreter necessarily must approach the Christological interpretation with some caution. Here again, however, diversity of opinion is found even though there is general agreement that the prophecy somehow relates to the Messiah of Israel. All Christological interpretations tend to interpret the first sixty-nine weeks as literal. The division comes on the interpretation of the seventieth week. Amillenarians generally regard it as following immediately after the sixty-ninth week and, therefore, already fulfilled in history. The other point of view regards the seventieth week as separated from the earlier sequence of years and scheduled for fulfillment in the future in the seven years preceding Christ’s second advent. Although many minor variations can be found, the principal question in the Christological interpretation of this text concerns the nature of fulfillment of the last seven years.

The prophetic period of time in question is declared to be “decreed,” which comes from a Hebrew word meaning “to cut, divide.”34 The idea is that the time period has been divided out or determined. The following timeline, as laid out by Gabriel, will occur because God has marked it out and determined it to be so. But can these weeks of years correspond to actual dates on a calendar? While Goldingay doesn’t believe they can, he acknowledges that “Ancient and modern interpreters have commonly taken vv. 24–27 as designed to convey firm chronological information, which as such can be tested by chronological facts available to us.”35

A very important aspect of the prophecy is that the seventy weeks relate to Daniel’s people and his city, Israel and Jerusalem. God’s answer corresponds to Daniel’s prayer, for these were the very subjects of his intercession (cf. vv. 16–19). Even in ruins, Jerusalem remained set apart in the heart of God (cf. 9:20) and Daniel shared this love for the city that is central in God’s program for His kingdom both in the past and the future. Unlike the prophecies of Daniel 2, 7, and 8, which primarily related to the Gentiles, this chapter is specifically God’s program for the people of Israel. To make this equivalent to the church composed of both Jews and Gentiles is to read into the passage something foreign to Daniel’s whole thinking. The church as such has no relation to the city of Jerusalem, or to the promises given specifically to Israel relating to their restoration and repossession of the land.

Gabriel enumerated six important purposes that God would accomplish during the period of the seventy weeks: (1) “to finish the transgression”; (2) “to put an end to sin”; (3) “to atone for iniquity”; (4) “to bring in everlasting righteousness”; (5) “to seal both vision and prophet”; and (6) “to anoint a most holy place.”

These six items are comprehensive in nature, and deserve to be considered in some detail. The first three deal with sin named in three ways. The expression “to finish” is derived from the piel verb form of the root kālâ, “to finish,” in the sense of bringing to an end. The most obvious meaning is that Israel’s course of apostasy and sin and dispersion over the face of the earth will be brought to completion within the seventy weeks. The restoration of Israel that Daniel sought in his prayer will ultimately have its fulfillment in this concept.

The second aspect of the program, “to put an end to sin,” may be taken either in the sense of taking away sins or bringing sin to final judgment.36 Due to a variation in textual reading, another possibility is to translate it “to seal up sin.” Keil translates this aspect, “to seal up sin,” and states, “The figure of the sealing stands here in connection with the shutting up in prison. Cf. ch. 6:18, the king for greater security sealed up the den into which Daniel was cast. Thus also God seals the hand of man that it cannot move, Job 37:7, and the stars that cannot give light, Job 9:7…. The sins are here described as sealed, because they are altogether removed out of the sight of God.”37

The final explanation may include all of these items because the eschatological conclusion of Israel’s history does indeed bring an end to their previous transgressions, brings their sin into judgment, and also introduces the element of forgiveness.38

The third aspect of the program, “to atone for iniquity,” seems to be a rather clear picture of the cross on which Christ reconciled Israel as well as the world to Himself (2 Cor. 5:19). As far as the Old Testament revelation of reconciliation is concerned, lexicographers and theologians have understood the Hebrew word kipper (atone), when used in relation to sin, to mean to “cover,” to “wipe out,” to “make … as harmless, non-existent, or inoperative, to annul (so far as God’s notice or regard is concerned), to withdraw from God’s sight, with the attached ideas of reinstating in His favour, freeing from sin, and restoring to holiness.”39

While the basic provision for reconciliation was made at the cross, the actual application of it is again associated with Christ’s second advent as far as Israel is concerned. Therefore, an eschatological explanation is possible for this phrase as well as a historical fulfillment. Peters relates Christ’s sacrifice to the kingdom specifically:

Following the Word step by step, it will be found that the sacrifice forms an eternal basis for the Kingdom itself. For it constitutes the Theocratic King, a Saviour, who now saves from sin without violation or lessening of the law, He having died “the just for the unjust,” and even qualifies Him as such a King, so that in virtue of His obedience unto death He is given authority over all enemies, and to restore all things…. The sacrifice affects the restoration of the Jewish nation; for when the happy time comes that they shall look upon Him whom they have pierced, faith in that sacrifice shall also in them bring forth the peaceable fruits of righteousness. The allegiance of the nations, and all the Millennial and New Jerusalem descriptions are realized as resultants flowing from this sacrifice being duly appreciated and gratefully, yea joyfully, acknowledged. It is ever the inexhaustible fountain from whence the abundant mercies of God flow to a world redeemed by it.40 [italics in original]

The final three items enumerated by Gabriel focus on the positive aspects of God’s prophetic program for His people, His city, and His sanctuary.41 The fourth aspect of the program is “to bring in everlasting righteousness.” There is a sense in which this also was accomplished by Christ in His first coming in that He provided a righteous ground for God’s justification of the sinner. The many messianic passages, however, that view righteousness as being applied to the earth at the time of Christ’s second coming may be the ultimate explanation. Jeremiah stated, “Behold, the days are coming, declares the LORD, when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, and he shall reign as king and deal wisely, and shall execute justice and righteousness in the land. In his days Judah will be saved, and Israel will dwell securely. And this is the name by which he will be called: ‘The LORD is our righteousness’” (Jer. 23:5–6). The righteous character of the messianic kingdom is also pictured in Isaiah 11:2–5 (cf. Isa. 53:11; Jer. 33:15–18).

The fifth aspect of the prophetic program about to be revealed to Daniel is “to seal both vision and prophet.” This is probably best understood to mean the termination of unusual direct revelation by means of vision and oral prophecy. This expression indicates that no more is to be added and that what has been predicted will receive divine confirmation in the form of actual fulfillment. Once a letter is sealed, its contents are irreversible (cf. 6:8). Young applies this only to the Old Testament prophet,42 but it is preferable to include in it the cessation of the New Testament prophetic gift seen both in oral prophecy and in the writing of the Scriptures. If the seventieth week is still eschatological, it would allow room for this interpretation.

The sixth aspect of the prophecy, “to anoint a most holy place,” has been referred to the dedication of the temple built by Zerubbabel, to the sanctification of the altar previously desecrated by Antiochus (1 Macc. 4:52–56), and even to the new Jerusalem (Rev. 21:1–27).43 Young suggests that it refers to Christ Himself as anointed by the Spirit.44 Keil and Leupold prefer to refer it to the new holy of holies in the new Jerusalem (Rev. 21:1–3).45 Gaebelein, expressing a premillennial view, believes the phrase “has nothing whatever to do with Him [Christ], but it is the anointing of the Holy of Holies in another temple, which will stand in the midst of Jerusalem,” that is, the millennial temple (Ezek. 43:1–5).46

There is really no ground for dogmatism here. The suggestion that it refers to the holy of holies in the New Jerusalem has much to commend itself. On the other hand, the other items all seem to be fulfilled before the second advent, and the seventieth week itself concludes at that time. If fulfillment is necessary before the second advent, it would probably rule out Keil, Leupold, and Gaebelein, although millennial fulfillment could be regarded as part of the second advent. The six items are not in chronological order, so it would not violate the text to have this prophecy fulfilled at any time in relation to the consummation. If complete fulfillment is found in Antiochus Epiphanes, as liberal critics conclude, or in Christ’s first coming as characterizes amillenarians like Young, this reduces the perspective. But if the final seven years is still eschatologically future, it broadens the possibility of fulfillment to the second advent of Christ and events related to it such as the millennial temple.

9:25 “Know therefore and understand that from the going out of the word to restore and build Jerusalem to the coming of an anointed one, a prince, there shall be seven weeks. Then for sixty–two weeks it shall be built again with squares and moat, but in a troubled time.”

The specific sequence of events begins with “the going out of the word to restore and build Jerusalem.” Daniel was to “know” the main facts of this prophecy, but it is questionable whether he actually understood it. Daniel later confessed that he did not understand every aspect of what had been revealed to him (Dan. 12:8), although the general assurance of God’s divine purpose must have comforted him. The history of the interpretation of these verses confirms the fact that this prophecy is difficult and requires spiritual discernment.

The key to the interpretation of the entire passage is found in the phrase “from the going out of the word to restore and build Jerusalem.” The question of the terminus a quo, the date on which the seventy sevens begin, is obviously most important both in interpreting the prophecy and in finding suitable fulfillment. The date is identified as being the one in which a commandment to restore and to build Jerusalem is issued.

As the history of the interpretation of this verse illustrates, a number of interpretations are theoretically possible. Young says the above expression “has reference to the issuance of the word, not from a Persian ruler but from God.”47 Young goes on to point out that the expression “the word” (Heb. dābār; cf. 2 Chron. 30:5) is also found in Daniel 9:23 for a word from God. He argues, “It seems difficult, therefore, to assume that here, two vv. later, another subject should be introduced without some mention of the fact.”48

It is rather obvious, however, that another subject has been introduced in verse 24 and the two commandments are quite different—that of verse 23 having to do with Gabriel being sent to Daniel and verse 25 having to do with the rebuilding of Jerusalem. Most expositors recognize that the word or commandment mentioned here is a commandment of men even though it may reflect the will of God and be in keeping with the prophetic word. Several commands were issued by the Persians in reference to Jerusalem:49

1. Ezra 1:1–4; 2 Chronicles 36:22–23. In 538 B.C. Cyrus king of Persia issued a decree to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem. The “house of the LORD” to be rebuilt is specifically said to be located in Jerusalem, but there is no mention in the decree of rebuilding the city itself. This also seems to be supported by the Cyrus Cylinder that records a similar command from Cyrus that allowed for the return of refugees and the rebuilding of sanctuaries but that made no mention of rebuilding cities. “I returned to (these) sacred cities on the other side of the Tigris, the sanctuaries of which have been ruins for a long time, the images which (used) to live therein and established for them permanent sanctuaries. I (also) gathered all their (former) inhabitants and returned (to them) their habitations.”50

2. Ezra 4:1–24. Ezra 4 provides a summary of several attempts to thwart the remnant who had returned from captivity. Though the passage begins and ends with the opposition that continued from Cyrus to Darius I (4:5, 24), the writer included events that extended beyond the time of the rebuilding of the temple, including attempts to rebuild Jerusalem, and this has caused some confusion. In 4:4–5 Ezra notes there was opposition during the reigns of Cyrus (559–530 B.C.) and Darius I (522–486 B.C.). He then described additional incidents of opposition (4:6–23) that occurred during the reigns of Xerxes (486–465 B.C.) and Artaxerxes I (465–424 B.C.). These specific events took place years after the completion of the temple. Then in 4:24 Ezra returned to the historical narrative regarding the rebuilding of the temple.

In the middle of the narrative on the temple Ezra did record one command issued by the Persians regarding the city of Jerusalem. In 464 B.C. the enemies of the Jews wrote to King Artaxerxes accusing the Jews of “rebuilding that rebellious and wicked city. They are finishing the walls and repairing the foundations” (Ezra 4:12). Artaxerxes then issued a decree “that these men be made to cease” (4:21). The temple had been completed by this time, but no permission had yet been given to rebuild the city. This command specifically prohibited the Jews from rebuilding the city of Jerusalem. And in light of the city’s continued state of disrepair twenty years later (Neh. 1:3) it is likely the charges made to the king that the Jews were “finishing the walls” had been wildly exaggerated.

3. Ezra 5:1–6:15. In 520 B.C. the Jews began rebuilding the temple. The governor of the region sent a letter of inquiry to King Darius asking if a decree had been issued allowing the work to go forward. Darius responded by reaffirming the earlier decree of Cyrus: “Let the work on this house of God alone. Let the governor of the Jews and the elders of the Jews rebuild this house of God on its site” (Ezra 6:7). There is no mention in the correspondence regarding any command to rebuild the city itself.

4. Ezra 7:13–26. In 457 B.C. King Artaxerxes sent Ezra to Jerusalem “to make inquiries about Judah and Jerusalem according to the Law of your God” (Ezra 7:14), but the remainder of the decree focused specifically on the temple and service of worship. Ezra was to use royal funds to purchase sacrifices and to deliver additional vessels “for the service of the house of your God” (7:19). Though the king’s edict does mention Jerusalem, there seems to be insufficient evidence to relate this directly to the prediction of Daniel 9.51

5. Nehemiah 2:1–6. In 444 B.C.52 King Artaxerxes sent Nehemiah to Jerusalem. Nehemiah asked permission to go because he had heard that “the wall of Jerusalem is broken down, and its gates are destroyed by fire” (Neh. 1:3). Nehemiah specifically asked permission to go to “Judah, to the city of my fathers’ graves, that I may rebuild it” (2:5). This is the first and only royal decree granting permission to “restore and build Jerusalem” (Dan. 9:25).

The amillennial interpretation of this passage, however, has usually considered the decree of Cyrus in 538 B.C. as the decree to rebuild the city and the wall. While acknowledging that 2 Chronicles and Ezra do not specifically mention a command to rebuild the city, they note what God predicted in Isaiah 44:28 and 45:13, remarkable prophecies given concerning Cyrus 150 years before he came on the scene. According to Isaiah 44:28, God said of Cyrus, “‘He is my shepherd, and he shall fulfill all my purpose’; even saying of Jerusalem, ‘She shall be built;’ and of the temple, ‘Your foundation shall be laid.’” In 45:13 God said of Cyrus, “[He] shall build my city and set my exiles free.”

Although Cyrus is not specifically identified in 45:13, God identified him by name as his “anointed” in verse 1. Young believes these verses indicate Cyrus did authorize the rebuilding of Jerusalem, and he finds confirmation of this in the statement in Ezra 4:12, where the enemies of Israel accuse the Jews of “rebuilding that rebellious and wicked city. They are finishing the walls and repairing the foundations.” Young, accordingly, concludes, “It is not justifiable to distinguish too sharply between the building of the city and the building of the temple. Certainly, if the people had received permission to return to Jerusalem to rebuild the temple, there was also implied in this permission to build for themselves homes in which to dwell. There is no doubt whatever but that the people thus understood the decree (cf. Haggai 1:2–4).”53

The question whether Jerusalem was rebuilt is answered in the graphic description of Nehemiah, which Young does not mention, that pictures the city in utter ruins (Neh. 2:12–15). He describes the walls as broken down, the gates burned, and the streets so full of debris that his mount could not get through. In his challenge to the people, Nehemiah said, “You see the trouble we are in, how Jerusalem lies in ruins with its gates burned. Come, let us build the wall of Jerusalem, that we may no longer suffer derision” (Neh. 2:17). Later, the people cast lots so that one in ten would have to move to Jerusalem and build a house there (Neh. 11:1).

It is rather evident, when all the evidence is in, that Jerusalem was not rebuilt in the sixth century B.C.—although the rebuilding of the temple was indeed the first step toward the restoration of the city and nation. The prophecies of Isaiah relating to Cyrus need to be understood in light of the more explicit information recorded in 2 Chronicles 36:22–23 and Ezra 1:1–4. It is most significant that none of the proclamations in 2 Chronicles or Ezra mention the city, only the temple.

Accordingly, the best explanation for the terminus ad quo in Daniel 9:25 is the decree relating to the rebuilding of Jerusalem itself given in Nehemiah 2:1–6, about ninety years after the first captives returned and started building the temple.

Many commentators identify this reference as the royal edict of Artaxerxes Longimanus, who reigned over Persia 465–425 B.C., and who not only commanded the rebuilding of Jerusalem in 444 B.C. but earlier had commissioned Ezra to return to Jerusalem in 457 B.C. (Ezra 7:11–26).54 The date 444 B.C. is based on the reference in Nehemiah 2:1ff. stating that the decree was issued in the twentieth year of Artaxerxes Longimanus. As his reign began in 465 B.C., twenty years later would be either 445 or 444 B.C. Most scholars accept the 445 B.C. date for Nehemiah’s decree, though the 444 B.C. date fits best with the Tishri dating system for Nehemiah proposed by Hoehner.55

The ultimate decision, to some extent, has to be determined by the fulfillment of the prophecy as a whole. Young’s explanation beginning it with the decree of Cyrus in 538 B.C. does not permit any reasonably literal interpretation of this prophecy. The 483 years that would then begin in 538 B.C., anticipated in the sixty-nine times seven years, would end in the middle of the first century B.C. when there was no significant event whatever to mark its close. This view makes any exact fulfillment impossible.

In verse 25, Daniel was introduced to two periods of time that are immediately consecutive: first a period of seven sevens, or forty-nine years, and then a period of sixty-two sevens, or 434 years. There is no clear indication as to why the two periods are distinguished, except that Gabriel added that Jerusalem “shall be built again with squares and moat, but in a troubled time.” In making a hard division between these two time periods it seems the ESV translators have departed from their philosophy of producing an “essentially literal” translation. A better literal rendering would be “Know and understand. From the going forth of a word to restore and rebuild Jerusalem until Messiah the Leader, [will be] seven weeks and sixty-two weeks.” The two time periods are connected and precede the coming of the Messiah or anointed one.

The first forty-nine-year period (“seven weeks”) does not fit Young’s explanation, since the period between the decrees of Cyrus (538 B.C.) and of Darius (520 B.C.) obviously was not forty-nine years. The best explanation seems to be that beginning with Nehemiah’s decree and the building of the wall, it took a whole generation to clear out all the debris in Jerusalem and restore it as a thriving city. This might well be the fulfillment of the forty-nine years, since Nehemiah said the city’s streets were so filled with debris that they were impassible in places. That this was accomplished in “a troubled time” is fully documented by the book of Nehemiah itself. Although the precise fulfillment is not a major item and only the barest of details are given, the important point seems to be the question of when the sixty-nine sevens (“seven weeks … and sixty-two weeks”) actually end. If the prophecy begins in 444 B.C., the date of Nehemiah’s decree, what is the end point?

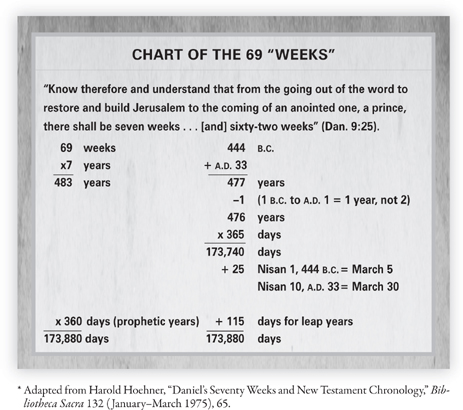

Anderson has made a detailed study of a possible chronology for this period, beginning with the assumed date of 445 B.C. when the decree to Nehemiah was issued and culminating in A.D. 32 on the very day of Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem shortly before His crucifixion. Anderson specifies that the seventy sevens began on the first of Nisan (March 14) 445 B.C. and ended on the tenth of Nisan (April 6), A.D. 32. The complicated computation is based upon prophetic years of 360 days totaling 173,880 days. This would be exactly 483 years according to biblical chronology.56

That Sir Robert Anderson is right in building upon a 360-day year seems to be attested by the Scriptures (see accompanying chart and the excursis at the end of the chapter). It is customary for the Jews to have twelve months of 360 days each and then to insert a thirteenth month occasionally when necessary to correct the calendar. The use of the 360-day year is confirmed by the forty-two months of the great tribulation (Rev. 11:2; 13:5) being equated with 1,260 days (Rev. 11:3; 12:6). While the details of Anderson’s arguments may be debated, the plausibility of a literal interpretation, which begins the period in 445 B.C. and culminates just before the death of Christ, makes this view very attractive.

The principal difficulty is Anderson’s conclusion that the death of Christ occurred in A.D. 32. While there has been uncertainty as to the precise year of Christ’s death based upon present evidence, most New Testament chronologers move it one or two years earlier, and plausible attempts have been made to adjust Anderson’s chronology to A.D. 30.57 But no one has been able dogmatically to declare that Anderson’s computations are impossible. Accordingly, the best end point for the sixty-nine sevens is shortly before Christ’s death anticipated in Daniel 9:26 as following the sixty-ninth seven. Practically all expositors agree that the crucifixion occurred after the sixty-ninth seven.

More recently, Dr. Harold Hoehner refined and updated the calculations of Anderson, based on additional historical information.58 He validated the basic methodology employed by Anderson while resolving some issues in Anderson’s chronology that he saw as problematic. Based on his revision, he believes the dates for the sixty-nine weeks of Daniel 9:25 extended from the first of Nisan (March 5) 444 B.C. to the tenth of Nisan (March 30) A.D. 33. (See the following chart for specific details.)

9:26 “And after the sixty-two weeks, an anointed one shall be cut off and shall have nothing. And the people of the prince who is to come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary. Its end shall come with a flood, and to the end there shall be war. Desolations are decreed.”

As noted earlier, the “sixty-two weeks” is best understood as being connected chronologically with the “seven weeks,” with both identifying the length of the time period between the command to rebuild Jerusalem and the coming of the “anointed one.” The ESV translation is unfortunate in this regard because it interjects a note of interpretive confusion that implies the “anointed one” was to arise after just “seven weeks.”

Most conservative expositors have interpreted “the anointed one” as a reference to Jesus Christ, who was “cut off” by His death on the cross. The verb rendered “to cut off” has the meaning “to destroy, to kill,” for example, in Genesis 9:11; Deuteronomy 20:20; Jeremiah 11:19; and Psalm 37:9.59

The word “anointed” was used of priests (Lev. 4:3, 5); Saul (1 Sam. 12:1–3; 24:5–6); David (2 Sam. 22:51; 23:1); the kings of Israel in general (1 Sam. 2:10; Lam. 4:20); Cyrus (Isa. 45:1); and of the future Messiah who was to come from the line of David (Pss. 2:2; 132:17–18). It initially referred to the fact that oil was poured over the heads of the priests (Exod. 28:41) and the kings (1 Sam. 10:1; 16:12–13) to set them apart to their responsibility before God. Ultimately, the word came to refer to the future king from the line of David who would arise to fulfill all God’s promises to Israel, that is, Jesus Christ.60 It seems best to understand Daniel using the word in this sense, especially since he identifies the Messiah as the future “leader,” a term used of Israel’s past kings like Saul (1 Sam. 9:16) and David (1 Sam. 13:14). Daniel’s audience would have understood “anointed leader” in a messianic context.

The prominence of the Messiah in Old Testament prophecy and the mention of Him in both verses 25 and 26 make the cutting off of the Messiah one of the important events in the prophetic unfolding of God’s plan for Israel and the world. How tragic that, when the promised King came, He was “cut off.” The adulation of the crowd at Christ’s triumphal entry and the devotion of those who had been touched by His previous ministry were all to no avail. Israel’s unbelief and the calloused indifference of her religious leaders when confronted with the claims of Christ combined with the hardness of heart of Gentile rulers to make this the greatest of tragedies.

Christ was indeed not only “cut off” from man and from life, but in His cry on the cross indicated that He was forsaken of God. The plaintive cry “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matt. 27:46) reveals not only the awfulness of separation from God, but points also to the answer—the redemptive purpose. The additional phrase in verse 26 “[he] shall have nothing” means that nothing which rightly belonged to Jesus as Messiah the Prince was given to Him at that time.61 He had not come into His full reward or the exercise of His regal authority. He was the sacrificial Lamb of God sent to take away the sins of the world (John 1:29). Outwardly it appeared that evil had triumphed.

Although evangelical expositors have generally agreed that the reference is to Jesus Christ, a division has occurred as to whether the event here described comes in the seventieth seventh described in the next verse, or whether it occurs in an interim or parenthetical period between the sixty-ninth seventh and the seventieth seventh. Two theories have emerged: the “continuous fulfillment” theory posits that the seventieth seven immediately follows the sixty-ninth; and the “gap” or “parenthesis” theory argues that there is a period of time between the sixty-ninth seven and the seventieth seven. If the fulfillment is continuous, then the seventieth week is already history. If there is a gap, there is a possibility that the seventieth week is still future. On this point, a great deal of discussion has emerged.

Once again, the fulfillment of the prophecy comes to our rescue. The center part of verse 26 states, “the people of the prince who is to come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary.” The destruction of Jerusalem occurred in A.D. 70, almost forty years after the death of Christ. Although some expositors, like Young,62 hold that the sacrifices were caused to cease by Christ in His death, which they consider fulfilled in the middle of the last seven years, it is clear that this does not provide in any way for the fulfillment of an event thirty-eight years or more after the end of the sixty-ninth seven. Young and others who follow the continuous fulfillment theory are left without any explanation adequate for interposing an event as occurring after the sixty-ninth seven by some thirty-eight years—which, in their thinking, would actually occur after the seventieth week since the temple is still standing in the final seven (Dan. 9:27). In a word, their theory does not provide any normal or literal interpretation of the text and its chronology.

The intervention of two events—namely, the cutting off of Messiah and the destruction of Jerusalem—after the sixty-ninth seven, which in their historic fulfillment occupied almost forty years, makes necessary a gap between the sixty-ninth seven and the beginning of the seventieth seven. Those referred to as “the people of the prince who is to come” are obviously the Romans and in no sense do they belong to Messiah the Prince. Hence it follows that there are two princes: (1) the Messiah of verses 25 and 26, and (2) “the prince who is to come,” who is related to the Romans. That a second prince is required who is Roman in character and destructive to the Jewish people is confirmed in verse 27 (see following exegesis), which the New Testament declares to be fulfilled in relation to the second coming of Christ (Matt. 24:15).

The closing portion of verse 26 is not entirely clear. But it seems to indicate that the destruction of Jerusalem will be like the destruction of a flood and that desolations are sovereignly determined along with war until the end. Because of the reference to “the end” twice in verse 26, it would be contextually possible to refer this to the end of the age and to a future destruction of Jerusalem. Revelation 11:2 says, “The nations … will trample the holy city for forty-two months,” a probable reference to the great tribulation just before the second advent. However, there is no complete destruction of Jerusalem at the end of the age, as Zechariah 14:1–3 indicates that the city is in existence although overtaken by war at the very moment that Christ comes back in power and glory. Accordingly, it is probably better to consider all of verse 26 fulfilled historically.63