2

Moral Crisis, Context, Call

“Before you finish eating your breakfast this morning, you’ve depended on more than half the world. This is the way our universe is structured . . . We aren’t going to have peace on earth until we recognize this basic fact of the interrelated structure of reality.”

Martin Luther King Jr.[1]

The following accounts depict people whose lives have intersected with mine. Their stories may be hard to hear; they were for me. These people have changed my life, causing torment and hope, defining my sense of what it means to be a person of God.

**********************************

A small World Council of Churches (WCC) team at a United Nations project gathered around a table to introduce ourselves to one another. When his turn arrived, one man uttered a single sentence in a voice of quiet power: “I am Bishop Bernardino Mandlate, Methodist bishop of Mozambique, and I am a debt warrior.” Later that week, when asked to address the United Nations Prep-Com meeting concerning the causes of poverty in Africa, Bishop Mandlate identified the external debt as a primary cause. The debt, he declared, is “covered with the blood of African children. African children die so that North American children may overeat.” [2]

“African children die so that North American children may overeat?” What can this man mean? How can this be? The bishop was speaking of the millions of dollars in capital and interest transferred yearly from the world’s poorest nations to foreign banks, governments, and international finance institutions controlled largely by the world’s leading industrialized nations.

A child who wakes up in Mozambique did not borrow any money, but she pays the price for her country’s heavy debt burden. Her country received loans packaged with the promise of development and immediate poverty alleviation but with conditions (established by lenders) that did not serve her people well. Often the loans were secured by corrupt leaders who pocketed or wasted much of the principal, but who are no longer around to be held responsible. Yet this child’s creditors still demanded payment.

In Mozambique, as in many other “heavily indebted poor countries,” the loans crippled real development rather than fostering it. [3] Julius Nyerere, while President of Tanzania, asked, “Should we really let our children starve so that we can pay our debts?” The debt repayments, while stunting the growth of many highly indebted poor nations, contributed to the wealth of already-wealthy countries. Bishop Mandlate’s words ring a note of horror in the heart for those of us whose economies benefit from the capital and interest paid by the world’s poorest nations.

“Frances,” a church leader from another African nation, was a part of the same WCC team. She spoke with quiet outrage of clothing donated by people in the United States and England to people in Africa whose livelihoods had been devastated when their small-scale local textile production was destroyed by U.S. trade practices. Under the name of “free trade,” very inexpensive textiles produced in the United States were “dumped” (sold at very low prices) in her nation. They undercut the Kenyan small-scale textile businesses, driving their owners—largely women—from self-sustaining livelihoods into poverty.

We move now to Mexico. While leading a delegation of local elected officials from the United States to Central America and Mexico, I came to know a Mexican woman who struggled to make a living picking strawberries. Her voice rings in my ears. “Our children,” she said, “die of hunger because our land which ought grow food for them, is used by international companies to produce strawberries for your tables.” Soon thereafter the Jesuit priest, Jon Sobrino, meeting with our group in his small office at the University of Central America in San Salvador, declared that for many people in El Salvador, “poverty means death. Our people are not poor due to their own fault or to bad luck. They are poor because the economic systems that create your wealth, make them poor.”

And what of the United States? Not long ago, I came to know a woman who lives in a shelter for homeless people in Seattle. Sharon (false name) works full time. Her job pays too little for her to afford even the least expensive available housing in the city. Probing further I learned that of Seattle’s 6,000 to 10,000 homeless people, many work at full-time or near full-time jobs. They are providing services to those of us who enjoy the low-cost goods that their cheap labor enables.

**********************************

The Moral Problem: Affluence and Poverty Linked

Our concern here is the moral implications of these and similar narratives. This book would not be necessary if we who are economically privileged did not care about the well-being of others. If self-interest were all that motivated our decisions and actions, then exploitation of others and of the Earth would not be so hard to explain.

This, however, is not the case. Most of us do care about others’ well-being; we don’t want them to suffer. Were someone to say to me, “Cynthia, shove the tribal people off of their lands in the Orissa province of India and kill the protesters because we need to mine bauxite from that land,” I would refuse. “Cynthia, your next task is to evict this woman from her tiny apartment. Her wages don’t cover the rent, and we will keep her at minimum wage in order to hold down the cost of your clothing and household goods.”

Were you, my reader, or I, asked to commit these deeds, we would exclaim “no,” crying out that such acts would betray our values, our sense of what it means to be a decent human being. Yet, we continue living according to economic practices and policies that effectively, albeit indirectly, follow these unacknowledged commands. This book asks, Why? What gives rise to acquiescence? What has prevented us from refusing such brutality over the years and today? What would enable us to live the opposite?

Nor would this book be necessary if the abject poverty of many were not connected to our overconsumption and to the public and corporate policies and practices that enable it. If that link did not exist, then charitable relief and assistance would be adequate responses to extreme poverty. The point is crucial. If, for example, factors leading to poverty in the Global South were internal to those nations or regions, then our moral obligation would be far different than it is, given our structured implication in others’ poverty and Earth’s distress. We would be called to generosity—to invest in health and education, infrastructure, technology, agricultural productivity, food and water supplies, and micro-business.[4] The moral question would be relatively simple: “How and how much ought we—who have more than enough—share our resources with people who live in abject poverty and hunger?”[5]

However, this question is an utterly inadequate and deceptive moral lens if we play a causal role in others’ impoverishment or benefit from it. Three questions reveal troubling moral connections: (1) Do we, relatively economically privileged U.S. citizens, play an indirect role—through public policy or U.S.-based corporate activity—in causing or perpetuating others’ poverty here in the U.S. or in other lands? (2) Do we benefit from that poverty or the factors that cause it? (3) Do we have tools and capacity for contributing to a changed situation? In large part, the response to these queries is yes.

Many factors lead to extreme poverty in the world’s most low-income countries. To be sure, in some cases, they are factors in which we play no causal role. However, in many circumstances underlying poverty in the poorest nations, we do play a significant role, one that often brings material wealth to some people in the United States. The questions apply likewise to poverty in the United States. The wealth of some is bought by policies and practices (low pay, lack of benefits, regressive taxation, access to ownership and education, and much more) that privilege people with wealth over those without.

With these realities, the moral pendulum swings away from the adequacy of charity. As expressed by Thomas Pogge, “If affluent and powerful societies impose a skewed global economic order that . . . makes it exceedingly hard for the weaker and poorer populations to secure a proportional share of global economic growth . . . such imposition is not made right by” assistance from the former.[6] If more affluent sectors within a society benefit from an economic order that makes it difficult for impoverished sectors in that society to secure a proportional share of wealth, charitable assistance does not make that injustice right. If affluent societies are disproportionately responsible for climate change, then “assistance” to the millions of climate refugees, while a moral imperative, is not a morally adequate response.

These connections hurl our moral world into tormenting tumult. Life lived in ways that cost other people their lives, where alternatives exist or are in the making and where political action toward them is possible, is not a moral life. To claim a moral life without seeking to challenge the systemic evil of which I am a part seems to me an absurdity.[7] The truth is that the structural violence depicted in these stories will not change unless some of us who benefit materially from it decide to recognize the problem and act on it.

Most of us do not play that causal role as individuals, but rather as parts of ongoing historical processes and social structures—economic, political, military, and other social systems. Three historical dynamics link our relative affluence and the severe poverty of others. The five-hundred-year legacy of colonialism is one. Another is ecological injustice.

The third dynamic is the currently reigning form of economic globalization, which gained ascendency in the early 1980s under the Thatcher and Reagan administrations. It is widely known as neoliberalism. Neoliberalism currently shapes life and death for millions. At its heart are “free trade,” financialization of economies, and the external debt of many impoverished nations. “Financialization” refers to the “increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors, and financial institutions in the operations of the domestic and international economies.”[8] Various forms of speculative investment are the core of financialization. Financialization redirects capital toward achieving short-range high profits for its owners despite the terrible costs to many others.[9] The recent global financial crisis was one result.

Two of these links—ecological injustice and neoliberal globalization—are maintained currently through policies and practices established by human beings. As humanly constructed, they can be challenged and changed. That is, perhaps, the most important point in this glimpse of the links between affluence and poverty.

Held together, these dynamics make possible the world as we know it and determine the life chances for millions of people worldwide. They may determine also the life chances of our children and grandchildren. Understanding these connections is a powerful tool for dismantling them. The Supplement to chapter 2 on this book’s webpage elaborates these historical dynamics linking affluence to poverty.

**********************************

A Life Story

International Hazardous Waste

Alma Bandalan and her three children, Justina, Elmer, and Dabie, used to live in a simple two-room nipa hut near the shore of Mactan Island in the central island region of the Philippines. Alma’s husband, Irwin, would head out well before dawn each day on a small wooden outrigger boat to catch fish for his family and to sell in the local mirkado. They were not wealthy but the sea usually provided food, and Alma was usually able to sell the fish along with some simple fruits and vegetables grown near their home.

And then—it seemed to almost occur overnight—resorts began to crop up left and right. And with the resorts came tourists. The stretch of beach on the east coast of Mactan Island had become prime real estate for tourism, with its clear waters and views out into the ocean, away from smoggy Cebu city. The Bandalans, their extended family, and all their neighbors were forcibly displaced to make room for a row of shiny beachfront resorts: the Maribago Bluewater Resort, the Hilton Cebu, and the Shangri-La.

Irwin Bandalan took a job as a jeepney fare-collector in Cebu city, hanging off the back of the brightly painted open-air buses in the exhaust-filled streets to make sure that passengers paid their seven pesos for each ride. Alma took the children into Cebu, but without the ocean to provide fish, the small plot of land to grow vegetables, or a roof under which to sleep, they became economically desperate. Finally, Alma found a position in a “recycling” center on the outskirts of the city. Justina, Elmer, and Dabie canvassed the massive piles of scrap metal during the day, looking for valuable parts. Alma worked inside, stripping down appliances that someone else far away had used. Her work required burning plastics and dipping materials in vats of acid. Within weeks, she began to experience skin and respiratory problems.

The children seemed worse off. All day they sifted through deconstructed machines, cords, plugs, wires, chips, metal, and plastic parts, inhaling toxic fumes and exposing themselves to lead, mercury, chromated copper arsenate, methylmercury, PCBs, and hundreds of other chemicals, the effects of which can be severe. Exposure to neurological toxins such as lead is poison to the developing brains of infants and children, even in tiny concentrations. Lead can paralyze the moving neurons within the growing brain of a child, limiting the child’s later learning and development. Lead exposure is associated with lower IQ, aggressive behavior, distractibility, and lower language skills. Alma’s children and several other children who lived and worked in this metal scrapyard began to display evidence of neurodevelopmental disorders: difficulties listening, speaking, memorizing, calculating, understanding. Levels of autism and mental retardation rose in this population, as well as ADD, ADHD, and dyslexia. Asthma was almost universal, and as carcinogens settled into these young bodies the seeds of later cancers were sown.

Alma’s choice was between destitution and poison. She chose the poison, and still ended up with a fair bit of destitution. The recycling center paid its workers less than a dollar per day to dismantle toxic scrap waste that came over from America on a ship. Some of the supposedly innocuous materials that arrived in shipping containers were in fact hazardous waste, often mislabeled as “scrap metal” and “material for recycling.” Officials at the nearby port in Mactan were too busy to inspect all containers, or sometimes accepted bribes to turn a blind eye to the hazardous materials entering the country. Often, they were simply deceived by the false labeling.

Jason and his college housemates inherited a blender from the apartment’s previous residents, but it had been acting up recently. On top of that, the scroll feature on Jason’s iPod stopped working. The blender, which was four years old and no longer covered by warranty, emitted a vaguely smoky smell, and the motor was weak. The iPod issue seemed isolated to one small area, but it was frustrating since the device was only a year old. Annoyed and eager to fix both, Jason began looking into repair options. He searched online for electronics repair shops but they were either too expensive or unable to fix the problem. His roommates all gave the same advice: “Just buy a new one.” “They’re getting cheaper—and you can upgrade while you’re at it.”

Jason’s mom agreed that he should just buy a new blender and iPod. She was in the process of remodeling her kitchen and was looking forward to upgrading all the appliances and installing a flatscreen TV on the kitchen wall. “Don’t we already have two TVs in the house?” Jason asked his mother. “Well yes,” she replied, “but this is so I can watch while I’m cooking dinner.” Jason didn’t push the issue, although he wondered what would happen to the old kitchen appliances that were probably still perfectly useful. That got him wondering just how many appliances now occupied his childhood home: stereo systems, electric toothbrushes, power tools, video game consoles, lamps, refrigerators, chargers for mobile devices, printers, air conditioners, a laundry machine, etc. His parents even had a charcoal broiler in the backyard that plugged in to an outdoor outlet.

Jason followed the advice of his friends and his mom, and soon life was back to normal, but with some shiny new electronics. He threw the blender in the trash, and added the iPod to the recycling, hoping that it would count as scrap metal.

This story continues in chapter 10.

Background to Life Story

“Transboundary dumping” refers to the export of waste products across national borders. On average, the residents of the richest countries throw away 1,763 pounds of trash each year, and much of that ends up in landfills in the Global South. As incinerators close in the North, incinerator developers often reopen the facilities in impoverished countries, where the municipal, medical, and hazardous waste of industrialized nations is burned. This constitutes a massive legal transfer of hazardous waste products from North to South, a process that harms public health as well as water, soil, and air quality. [10]

One form of “transboundary dumping is electronic waste, or “e-waste.” This refers to discarded laptops, cell phones, refrigerators, washers, dryers, air-conditioner units, fluorescent light bulbs, stereos—essentially any gadget or appliance that runs off electricity. Personal computers are the most visible and harmful component of electronic waste. These and other electronic goods discarded by consumers in the Global North are often shipped to Asia or Africa where residents disassemble them for sale in new manufacturing processes or where they are dumped as waste. Most electronics contain high levels of toxic materials. Computer monitors alone house cathode ray tubes with four to eight pounds of lead, not to mention numerous other toxins. When these monitors end up in landfills, they are crushed and the lead releases into the soil and atmosphere. Toxins don’t impact only the environment and those who live in it, but the workers who transport, load, unload, and manage the waste.

Some critics argue that the United States is not a major contributor to international trade in hazardous waste, because the U.S. only exports a small fraction of all hazardous waste produced domestically. This claim is misleading, because most toxic waste exported out of the U.S. is designated as recycling or scrap metal.

**********************************

A Twofold Moral Crisis: Economic and Ecological

The moral crisis screams. Its ecological and economic dimensions are inextricably intertwined, and are unprecedented in the history of humankind.

Ecological

One young and dangerous species now threatens Earth’s capacity to regenerate life as we know it. Homo sapiens are using and degrading the planet’s natural goods at a rate that Earth’s ecosystems cannot sustain. We have generated an unsustainable relationship with our planetary home. The credible scientific community is of one accord about this basic reality and hundreds of its widely respected voices have been for over two decades.[11]

The 2005 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment—the most comprehensive sustainability assessment ever undertaken—proclaimed that “human activity is putting such a strain on the natural functions of the Earth that the ability of the planet’s ecosystems to sustain future generations can no longer be taken for granted.”[12] In the midst of unprecedented “spending” of Earth’s natural bounty—food, fresh water, wood, climate and air, and so on—it is now “time to check the accounts . . . and it is a sobering statement with much more red than black on the balance sheet.”[13]

Now seven years past this study, the signs are yet more ominous. The IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report of 2007, based on scientific analysis and data of over 3800 scientists from more than 150 countries, reveals that global warming is accelerating far more rapidly that projected in earlier reports.[14] The polar ice caps are melting far more rapidly than predicted at that time. The loss of ice, in turn, hastens global warming; as the cooling impact of the protective ice layer diminishes, earth absorbs more sunlight. The litany of perils is now familiar. Rise in sea levels “threaten[s] low-lying areas around the globe with beach erosion, coastal flooding, and contamination of freshwater supplies. . . . Even major cities like Shanghai and Lagos would face similar problems, as they also lie just six feet above present water levels.”[15] The Maldives, a low-lying island nation, is threatened with loss of its entire land. The nation could be forced to relocate.

Catastrophic impacts on food production have begun and will increase for already-impoverished people. “Even slight warming decreases yields [of major cereal crops: wheat, corn, barley, rice] in seasonally dry and low-latitude regions. . . . Smallholder and subsistence farmers, pastoralists and artisanal fisherfolk will suffer complex, localized impacts of climate change . . . [including] spread in prevalence of human diseases affecting agricultural labor supply.”[16]

The United States too will experience rising seas. “Scientists project as much as a 3-foot sea-level rise by 2100. According to a 2001 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency study, this increase would inundate some 22,400 square miles of land along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States, primarily in Louisiana, Texas, Florida and North Carolina.” Loss of Arctic ice will affect weather and with it food production in the U.S. “Loss of Arctic ice would affect wheat farming in Kansas, for example. Warmer winters are bad news for wheat farmers, who need freezing temperatures to grow winter wheat. And in summer, warmer days would rob Kansas soil of 10% of its moisture, drying out valuable cropland.”[17]

In a word, humankind has become a menace to life on Earth. Gus Speth, former Dean of the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies at Yale University, speaking of the factors behind environmental deterioration, avers:

The much larger and more threatening impacts stem from the economic activity of those of us participating in the modern, increasingly prosperous world economy. This activity is consuming vast quantities of resources from the environment and returning to the environment vast quantities of waste products. The damages are already huge and are on a path to be ruinous in the future. So, a fundamental question facing societies today—perhaps the fundamental question—is how can the operating instructions for the modern world economy be changed so that economic activity both protects and restores the natural world?[18]

Economic

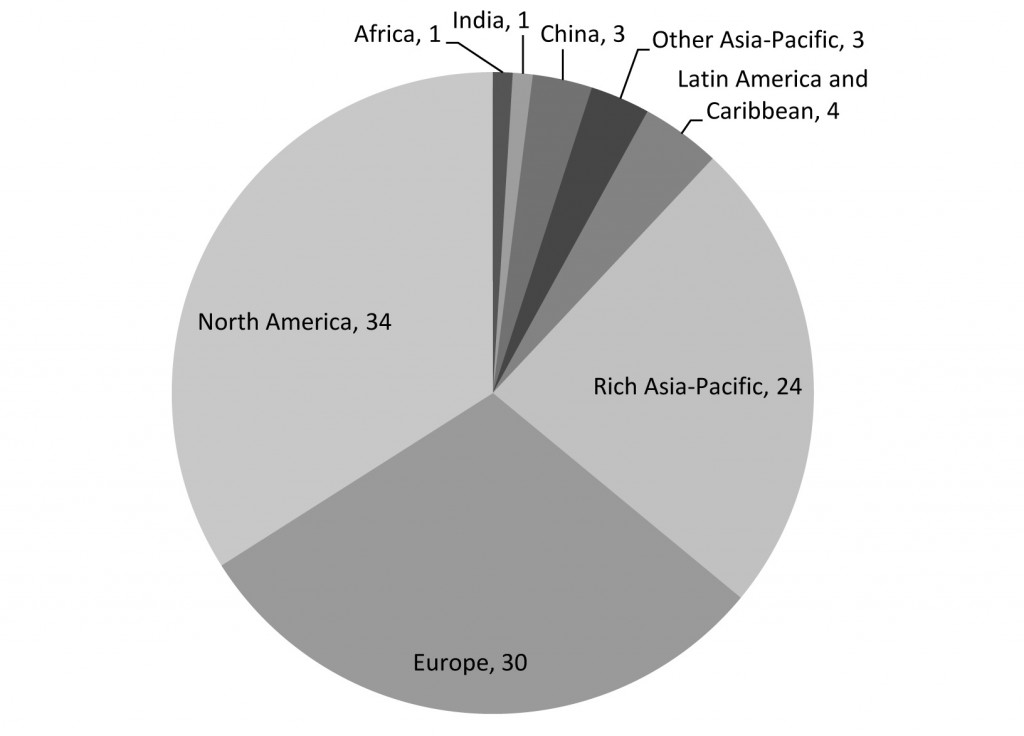

The ecological dimension of the crisis is accompanied by an economic justice dimension, produced by many of the same political-economic dynamics. We have created and are deepening a morally reprehensible gap between those who “have too much” and those who have not enough for life or for life with dignity. “Global inequalities in income increased in the twentieth century by orders of magnitude out of proportion to anything experienced before. The distance between the incomes of the richest and poorest country was about 3 to 1 in 1820, 35 to 1 in 1950, 44 to 1 in 1973 and 72 to 1 in 1992.”[19] Recent reports indicate the distance to be nearing 100 to 1. The diagram of wealth distribution on the next page tells part of the story.

The facts are numbing. A comprehensive study of wealth distribution released in December 2006 by the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research reports that the richest tenth of the world’s adults owned 85 percent of global assets in the year 2000. The poorest half, in contrast, owned barely 1 percent.[20] A previously issued United Nations report showed similar findings: 225 people now possess wealth equal to nearly half of the human family.[21] The number of children under age five who die each day, mostly of poverty-related causes, equals roughly 26,000.[22] Pause for a moment, to resist letting these numbers drift by unconsidered.

.

Regional Wealth Shares (%)

“Metrics 2.0 Business and Market Intelligence” using data from World Institute for Development Economics Research of the United Nations University (UNU-WIDER), The World Distribution of Household Wealth, December 2006.

This diagram misses a crucial part of the story. On it, North America appears as one section. Regional wealth figures, however, hide vast inequities in wealth and income distribution. Wealth in the United States is highly concentrated, with income disparity rising dramatically since the late 1970s (the beginning of neoliberal economic globalization) and reaching its highest recorded level in 2007.[23] The wealthiest 1 percent now owns nearly 43 percent of financial wealth (defined as net worth excluding the value of one’s house), while the bottom 80 percent owns only 7 percent.[24] Imagine, then, an accompanying chart revealing a United States of ten people in which one of them owns close to half the wealth and eight of the people have a mere 7 percent.

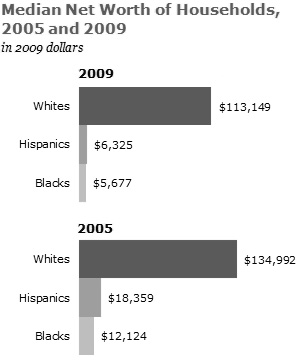

Our imaginary chart of wealth and income distribution in the U.S. would reveal more if coded for gender and race. As Christian ethicist Pamela Brubaker demonstrates, “single female-headed families [in the United States] have the lowest median family income . . . and the biggest drop in income of any group between 2007–10.”[25] Drawing upon the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, she reports that, “‘Black and Hispanic workers of both sexes earn considerably less than white males, but the gap in earnings is particularly marked for women in these groups. The median income of Latinas is 54.5% of white men’s.”[26] In the recent economic downturn, Hispanic and black families lost far more in net worth than did white families. “From 2005 to 2009, inflation-adjusted median wealth fell by 66% among Hispanic households and 53% among black households, compared with just 16% among white households.”[27] While a few Americans became much richer, far more—disproportionately people of color and women—were thrust more deeply into poverty.[28]

Most unsettling of all from a moral perspective is this: poverty on a global and domestic basis is directly related to what Pope John Paul II called “inadmissible overdevelopment.” By this he means an economic order that enables a few of us to consume a vast proportion of Earth’s life-enabling gifts, while many others die or suffer for want of “enough,” and in which the poverty of many is linked to the wealth of others.[29] Vigorously avoided in common knowledge, for example, is the reality that famine often is not the result of insufficient food supplies. It is the result of maldistribution of land and income.[30] And the distribution of the world’s food supplies is determined by the decisions, policies, and actions of the world’s powerful nations and people.[31]

The global wealth gap, like wealth inequity in the U.S., is shaped around color lines. Worldwide, people of colors other than white are overwhelmingly among the economically impoverished. “Massive poverty and obscene inequality are such terrible scourges of our times,” declared Nelson Mandela in 2005, “that they have to rank alongside slavery and apartheid as social evils.”[32]

Climate Injustice and Environmental Racism

Ecological and social justice dimensions of the “Earth crisis” are inseparable. The connections are not hard to see. They take many forms, two of which are climate injustice and environmental racism.

United States citizens, to illustrate the former, daily produce roughly forty times the greenhouse gases per capita as do our counterparts in some lands,[33] while the world’s more impoverished people and peoples suffer most and first from the more life-threatening consequences of global warming.[34] White privilege also marks the climate crisis. The over six hundred million environmental refugees whose lands will be lost to rising seas if Antarctica or Greenland melt significantly will be disproportionately people of color, as are the twenty-five million environmental refugees already suffering the consequences of global warming. So too will be the people who starve as global warming diminishes crop yields of the world’s three staples—corn, rice, and wheat. The 40 percent of the world’s population whose lives depend upon water from the seven rivers fed by rapidly diminishing Himalayan glaciers are largely not white people.

Moreover, impoverished countries are less able to implement adapting strategies than are we of the industrialized world. The United Nations Human Development Report 2007 explains: “While the world’s poor walk the Earth with a light carbon footprint they are bearing the brunt of unsustainable management of our ecological interdependence. . . . Cities like London and Los Angeles may face flooding risks as sea levels rise, but their inhabitants are protected by elaborate flood defense systems. By contrast, when global warming changes weather patterns in the Horn of Africa, it means that crops fail and people go hungry.”[35] These are examples of what many voices from the Global South refer to as “climate injustice” or “climate imperialism.”

The social inequity and ecological degradation nexus takes a second form—“environmental racism.” The term was coined in 1987 by Benjamin Chavez, an African American civil rights leader, in the groundbreaking study, “Toxic Wastes and Race,” commissioned by the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice. “Environmental racism” refers to governmental or corporate policies and decisions that “target certain communities for least desirable land uses, resulting in the disproportionate exposure of toxic and hazardous waste on communities based upon certain prescribed biological characteristics.” It is the “unequal protection against toxic and hazardous waste exposure and systematic exclusion of people of color from environmental decisions affecting their communities.”[36]

Illustrations of environmental racism are countless. The aforementioned study documented the disproportionate location of facilities for treatment, storage, and disposal of toxic waste materials in or near racial and ethnic minority communities in the United States. And it found that the disproportionate number of racial and ethnic minorities living in communities with commercial hazardous waste facilities was not a random occurrence but rather a consistent pattern. More recent studies bear similar findings.[37] The term, while initially referring to environmental discrimination based on race alone, has also come to denote the disproportionate distribution of environmental dangers in communities of economically marginalized people.

**********************************

Sitting in the sparsely furnished basement office of a social movement organization in Dehli, I looked up to see a small dark-skinned woman enter the room. Obviously ill at ease, yet bearing a simple dignity, she spoke very little. Hers was a tribal language accompanied by the subtle nodding of the head typical of many Indian tribal peoples. A thin quiet child clung to her hand, enabled to breathe by a tube situated in his throat. He and his mother were to spend the night in the office, having come a long distance by bus to receive medical care for the child. His mother’s exposure to toxic gas leaked by the Indian subsidiary of Union Carbide in Bhopal caused his birth defect. The leak killed thousands of people and caused long-term grave injury in tens of thousands.

That leak would not have happened in a wealthy neighborhood of the United States.

**********************************

The ongoing grind of “hidden” environmental racism is ubiquitous. Our food, clothing, transportation, housing, and consumption are built on it. “The production chain of textiles is a sequence of poisons: cotton fields are sprayed with chemical cocktails to which the workers are also exposed without protection and which subsequently contaminate the soil. In spinning and weaving factories, workers are exposed to dust as the dyers later are to fumes from the dye.” The razing of rainforests for cattle strips livelihood and home from many of the world’s 350 million forest dwellers. The beneficiaries are the corporations responsible and “we,” the consumers. Neither bear the environmental and human costs. The victims are disproportionately not white.

The transfer of ecologically dangerous production plants and toxic waste in mass quantities to countries of the Global South are two further manifestations of environmental racism on a global level. In the former, U.S.-based corporations close plants in the United States and move them to Mexico, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, and elsewhere in order to avoid environmental and labor regulations and taxes. Lawrence Summers, President Emeritus of Harvard University and former Secretary of the Treasury (1999–2001) “is infamous for writing a 12 December 1991 memo as a chief economist at the World Bank that argued that ‘the economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest wage country is impeccable,’ and that the Bank should be ‘encouraging more migration of the dirty industries to the LDCs [less developed countries].’”[38]

Thus we see two broad dimensions of the link between social injustice and ecological degradation: climate injustice and environmental racism. Together on the global stage, they are known by some as “ecological imperialism.” The term is gaining currency in both secular and theological discourse as a means of expressing the social justice–ecology link on a global scale. Julian Agyeman, Robert Bullard, and Bob Evans summarize it well:

While the rich can ensure [at least for the time being] that their children breathe cleaner air . . . and that they do not suffer from polluted water supplies, those at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder are less able to avoid the consequences of motor vehicle exhausts, polluting industry and power generation or the poor distribution of essential facilities. This unequal distribution of environmental ‘bads’ is, of course, compounded by the fact that globally and nationally the poor are not the major polluters. Most environmental pollution and degradation is caused by the actions of those in the rich high-consumption nations, especially by the more affluent groups within those societies . . . [yet] affluent countries in the North are avoiding or delaying any real reduction in their greenhouse gas emissions.[39]

Religious and secular voices concerned with social justice caution that efforts to address climate change and other aspects of the earth crisis will either exacerbate or reduce existing injustice based in race/ethnicity, gender, and class. This concern demands holding social justice and ecological well-being as inseparable in the quest for a sustainable relationship between the human species and the planet. Eco-justice is a term for that linkage.

**********************************

Amidst a cacophony of bleating car horns, a tiny cab maneuvered through darting motorbikes and weaving rickshaws packed with young women in flowing saris, zipped past hungry beggars, and veered into a calmer, greener space. It was the modest headquarters of the National Council of Churches of India. Simple, dormitory-like dwellings with screened porches joined a larger building surrounded by trailing plants. From it slowly emerged fifteen or twenty smiling men and women conversing, I soon realized, in at least two or three languages. They converged around a banner and, with rather tired but spirited smiles, stood together for a snapshot recording their shared work. High-level leaders of Christian denominations and networks throughout India, they had been gathered by the National Council of Churches of India to design an “eco-justice Sunday School curriculum” to be used throughout the nation.

The next day would begin a second consultation, in which I had been invited to participate as a co-planner and a presenter. It convened thirty-some professors of theology from throughout India and Sri Lanka who taught or were preparing to teach green theology and eco-justice as a required component of graduate-level education in theology and ministry. They were people of courage and commitment. They were teaching eco-justice because the lives of their people depended upon it and because they understood it as integral to faith in God.

Eco-justice ministries had many faces for the people that I came to know in this brief consultation. One young woman pastor who helped to facilitate the consultation, had been assigned to ministry in the state of Orissa. Her work was with tribal people who for years had been organizing and risking their lives to resist the international Bauxite mines that were destroying their lands and driving them from their communities. She had once walked with other village women for two days in rough and dangerous terrain bearing the body of a person killed in the movement of resistance to the mines.

Two others were faculty at a seminary near Sir Lanka’s Negombo Lagoon. The lagoon had been a means of life for the area’s people for centuries. That source of food, employment, culture, community, and homes was falling prey to the foreign-owned tourist industry and a nearby Free Trade Zone. The once life-giving lagoon was being converted to a landing strip for sea planes serving tourists. Production plants in the Free Trade Zone were poisoning the water with chemicals and garbage. Seafood supplies were fast diminishing, and the shores from which fisherpeople had once launched boats and nets now boasted high-end hotels and restaurants. Simple homes were being replaced by tourist facilities, and the longtime dwellers displaced into urban poverty. Eco-justice ministry was, for the professors from this area, a matter of life and death for their people.

**********************************

Eco-Justice

Countless individuals, groups, and networks around the globe strive persistently toward eco-justice. This movement has at least two streams. One is the environmental justice movement, and the other is the climate justice movement.[40] These two overlapping movements respond to environmental racism and climate injustice respectively. The two streams are rapidly converging as the links between climate injustice and environmental racism become clearer and more insidious.

Eco-justice calls forth the morally and politically charged questions of “ecological debt” and “environmental space” elaborated in chapter 8.[41] The former holds that overconsuming countries of the Global North owe an “ecological debt” to those who suffer most from ecological degradation but contribute least to it. Ecological debt theorists suggest also that we owe an ecological debt to future generations for what we have taken from them through climate change, ocean acidification, loss of biodiversity, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and more. “Environmental space” is a rights-based and equity-based approach to eco-justice. It suggests that all people have rights to a fair share in the goods and services that Earth provides to humankind.

A dangerous intellectual and moral fault line of the environmental movement in the United States has been the seductive temptation to disassociate Earth’s degradation from the pernicious forms of social injustice madly eating away at our lives (yet largely unseen by people of the upperside of power and privilege). The eco-justice movement counters this problem.

A Shift in the Discourse: Theft Acknowledged

Earlier we noted three historical trends that have produced relative wealth for some people while impoverishing and at times brutalizing multitudes (colonialism, the reigning form of economic globalization known as neoliberalism, and ecological injustice). Frequently in these dynamics, economic and ecological violence have worked in concert, in the past and today. The result is collective theft, historical and ongoing. That the theft is, for most of us, unintentional makes it no less deadly. It is a central moral transgression of our lives. It is a form of systemic sin in which we take part.

The pathos of our situation stuns. We may desire to make this world a better place and strive earnestly to do so. Yet, our lives have become deadly to the very life-systems that enable life on earth—air, water, soil, biodiversity—and to countless people who have died and continue to die in the wake of European conquest of Africa, the Americas, and parts of Asia, and the economic colonialism and ecological degradation that have followed.

As Thomas Pogge writes, given these dynamics, our failure to address them and to reduce poverty “may constitute not merely a lack of beneficence, but our active impoverishing, starving, and killing millions of innocent people by economic means. To be sure we do not intend these harms. . . . We may not even have foreseen these harms when we constructed the new global economic architecture in the late 1980s. . . . So perhaps we made an innocent and blameless mistake. . . . But it is our mistake nonetheless, and we must not allow it to kill yet further tens of millions in the developing world.”[42] The issue is accepting active responsibility for our participation in structural evil.

Our Moment in History

Something New Required of Humankind

Our moment in history is breathtaking. The generations of people now living will decide whether or not life continues on this planet in ways recognizably human and verdant. In this context, something new is required of humankind: to forge ways of being human that do not threaten Earth’s life-sustaining capacity, and that vastly diminish inequity in access to the necessities for life with dignity. We are beckoned toward the fourth great revolution in the brief history of our species (following the agricultural, industrial, and informational revolutions), an ecological revolution that is simultaneously an unrelenting commitment to social equity.[43] All fields of human inquiry are called upon to contribute to this pan-human interfaith “great work” of our day.

For humankind to achieve a sustainable relationship with our planetary home, the economic order that we assume as a given—advanced global capitalism and ways of life in accord with it—is not an option. This is not an ideological statement or a political or moral opinion. It is a statement about physical reality. Earth as a biophysical system cannot continue to operate according to the defining features of capitalism as we know it. Capitalism as it has developed from classical economic theory, through neoclassical theory and on to neoliberalism, aims at and presupposes what Earth can no longer provide or provide for:

- Unlimited growth in production of goods and services.

- Unlimited “services” (required for unlimited growth) provided by Earth. Those services include “soil formation and erosion control, pollination, climate and atmosphere regulation, biological control of pests and diseases,” and more.[44]

- Unlimited “resources” (required for unlimited growth) provided by Earth, such as oil, coal, timber, minerals, breathable air, cultivable soil, air with a CO2 concentration of somewhere between 275 and 350 parts per million,[45] oceans with a balanced pH factor, the ocean’s food chain, potable water, etc.

- An unregulated market in which the most powerful players are economic entities having:

- a mandate to maximize profit

- the legal and civil rights of a person

- limited liability

- the legal right and resources to achieve size larger than many nations

- no accountability to bodies politic, be they cities, states, nations, or other

- the right to privatize, own, and sell goods long considered public.

- Freedom of individuals to do as they please with economic assets (including unlimited carbon emissions and speculative investment that may result in the economies of nations crashing).

The Earth can no longer provide or support these requirements of unregulated corporate- and finance-driven fossil-fueled global capitalism. Hence, carrying on indefinitely with advanced global capitalism—economic life as we know it—is not an option.[46] The option is something different. (Clearly that “something different” is not state socialism, which is yet another form of centralized economic power dedicated to growth and unaccountable to a democratic public.)

This is not a stand against business. It is a stand for business that is not dominated by mega-corporations, business that is not entitled to the rights of a citizen and compelled by a mandate to maximize profit. And it is an appeal for business to become an active force of ecological sustainability and restoration. Moreover, it is a firm appeal to resituating the market as one instrument of society, rather than the determining actor in society.

While we have no choice in whether or not economic life will change dramatically, we have tremendous choice about the nature of that change. Enter here ethics and morality. Humankind understands itself to be a moral species. We determine (or seek to determine) how to live together based not only on brute force, bare necessity, or survival of the fittest, but on what whatever we deem to be right, true, and good.

What are the options for the economic order following corporate and finance-driven, fossil-fueled global capitalism? The default option is to try to carry on with the economy largely as it is while establishing a few regulations related to carbon emissions and pollution. The consequence—relatively unchecked climate change—is horrific.

Another possibility would be serious concerted efforts to mitigate climate change, without also questioning some basic market norms, such as the assumption that certain rights (the right to potable water, protein sources, nontoxic food, clean air, and so on) are based on ability to pay. This option would continue to grant a few people of the Global North disproportionate use of the atmosphere and oceans for absorbing carbon emissions. This group also would continue to have relatively greater protection from floods, hurricanes, and other climate-related “natural” disasters. As crops and water supplies diminish, this group would consume an increasingly disproportionate share of them. Where this option would lead, we do not know. We do know that it would produce millions of environmentally caused deaths in Asia and Africa.

Or we could choose to move toward economic orders shaped by other norms. This book will propose four. They are ecological sustainability, environmental equity, economic equity, and distributed accountable power. Said differently, we would aim toward economies that:

- operate within, rather than outside of, Earth’s great economy.

- move toward more equitable “environmental space” use.

- move toward an ever-decreasing gap between the world’s “enriched” and “impoverished” people and peoples, and prioritize need over wealth accumulation.

- are accountable to bodies politic (be they of localities, states, nations, or other), and favor distributed power over concentrated power.

At first glance, these aims may seem far beyond the realm of the possible. I will argue the opposite.

Let us assume, for a moment, adequate moral courage and political will to move toward economies shaped by the four aforementioned norms. A flock of birds flying gracefully through the sky presses forward in one direction. Then, in a flash and as a whole, a great swoop occurs and they are off in an utterly different direction. The radical change to which we are called is that dramatic: an “utterly different direction.” The birds have an ingrained mechanism that enables them to redirect themselves radically as a whole and with tremendous grace and apparent ease. We don’t. We must forge an unknown path, step by step, piece by piece. The only way to get there is to go there. We will end up in the direction that we head. Needed is an ethic for this move toward more sustainable, equitable, and democratic economic orders. This book is one small contribution to that ethic.

Something New Required of Religion and Religious Ethics

When something new is required of humankind, something new is required of Earth’s longstanding faith traditions, primary sources of moral wisdom and moral courage. They are called to plumb their depths for relevant moral-spiritual wisdom, and to offer those gifts to the table of public discourse and decision making. Herein we consider one constellation of these faith traditions: Christian traditions. Christian theology and practice are replete with invaluable contributions to offer. People located within Christian traditions are responsible to wrestle with them, demanding and trusting that they will yield guidance for movement into ecologically sound and socially just societies. This means engaging Christian sources—biblical narratives, the lives and writings of faith forebears, church teachings, liturgical practices, moral norms—insistent on seeing both where they have led us astray (contributed to the ecological-economic crisis) and where they offer sound counsel and resources. Where Christian beliefs and practices have contributed to the Earth crisis, we are called to critique and “re-formation.” Where the resources of Christian traditions reflect God’s boundless love for creation and offer moral power for the good, we must grasp their depths, and tender them to the broader community. Similar opportunity and responsibility sits on the shoulders of people within the other religious traditions.

Moving On

In this chapter we faced the moral challenge of affluence linked to poverty and ecological devastation, and examined eco-justice—a wedding of ecological well-being and economic justice. Finally, we posited the inevitability of dramatic economic change imposed by Earth’s limitations, and previewed the four norms that guide movement toward more life-giving alternatives.

The reality that “we” (the overconsuming classes) are inextricably connected with neighbors far and near by virtue of our food, clothing, shelter, transportation, recreation, and more is a given. So too is the fact that our lives have monumental impacts on Earth’s life-systems. These connections will grow more significant as water, fish, and oil become more scarce and climate change more pronounced. However, and this is the crucial point, the terms of our relationships with other human beings and with the other-than-human parts of creation are not given. They are constantly determined by human decision and actions—based in part upon what we choose to see and what we choose to ignore. Determining the extent to which those relationships continue to breed death and destruction or nurture the opposite is the core moral and theological challenge of the twenty-first century.

- Martin Luther King Jr., “A Christmas Sermon on Peace,” sermon preached at Ebenezer Baptist Church, December 24, 1967.↵

- Bernardino Mandlate, in presentation to the United Nations PrepCom for the World Summit on Social Development Plus Ten, New York, February 1999.↵

- In Haiti and other countries, for example, dams were built that benefited relatively few people while displacing far more people (usually impoverished people).↵

- These are core investments needed to reach seven of the eight Millennium Development Goals.↵

- The question is not in actuality “simple,” only relatively so. The question is complexified by multiple factors: finite resources versus infinite needs, how to share across international boundaries, determining how much of what I have I need and how much I to ought share, and so on.↵

- Thomas Pogge, “Priorities of Global Justice,” Metaphilosophy 32, no. 1/2 (January 2001): 16–17.↵

- This stance presupposes the situation of “economically privileged” citizens in a nation with constitutionally “guaranteed”—albeit not universally upheld—civil and political rights.↵

- The term “financialization” in fact has varied definitions. For an accounting of them, see Gerald Epstein, “Introduction: Financialization and the World Economy,” in Gerald Epstein, ed., Financialization and the World Economy (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2005), 3.↵

- Financialization was enabled, in part, by redesigning regulatory regimes established in the New Deal era. They—most notably the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933—had been established to prevent banks from risking depositors’ money in stock markets, and to prevent single financial institutions from dominating financial markets. For the shift of financial flow from goods/services to speculative investment, see L. Randall Wray, “Monetary Theory and Policy for the Twenty-first Century,” in Charles Whalen, ed., Political Economy for the Twenty-First Century (New York: Sharpe, 1996).↵

- David Naguib Pellow, Resisting Global Toxins: Transnational Movements for Environmental Justice (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 186.↵

- See “Warning to Humanity,” issued in 1992 by 1600 of the world’s senior scientists, including a majority of all living Nobel Laureates in the sciences.↵

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005, was written by nearly one thousand of the world’s leading scientists in biological fields. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005. "Ecosystems and Human Wellbeing: Biodiversity Synthesis." World Resources Institute, Washington, DC. http://www.maweb.org/en/index.aspx.↵

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005, “Natural Assets and Human Well-Being,” 5.↵

- M. L. Parry, O. F. Canziani, J. P. Palutikof, P. J. van der Linden, and C. E. Hanson, eds., Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2007 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).↵

- National Resources Defense Council at www.nrdc.org/globalwarming/qthinice.asp.↵

- Parry et al., Contribution of Working Group II.↵

- National Resources Defense Council at www.nrdc.org/globalwarming/qthinice.asp.↵

- James Gustave Speth, The Bridge at the End of the World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008).↵

- United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report, 2000 (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 6.↵

- James Davies, Susanna Sandstrom, Anthony Shorrocks, Edward Wolff, The World Distribution of Household Wealth (UNU-WIDER, 2006). “Wealth” in the study means “net worth.”↵

- United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report, 1998 (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 29–30.↵

- “State of the World’s Children Report 2008,” UNICEF, 6. For additional figures on global poverty, see “Fast Facts: The Faces of Poverty,” at www.unmilleniumproject.org/resources.↵

- Timothy Noah, “The United States of Inequity: The Great Divergence,” Slate, September 2010.↵

- UCSC professor, William Domhoff in www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html.↵

- $29,220 median and 2.8 percent drop. Pamela Brubaker, “Class and Power,” unpublished paper.↵

- Pamela Brubaker, “Class and Power,” ibid., citing Ariane Hegewisch and Claudia Williams, “Gender Wage Gap 2010,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research. September 2011.↵

- Pew Research Center, “Wealth Gaps Rise to Record Highs Between Whites, Blacks and Hispanics,” Washington, D.C., 2011, 1. It goes on: “As a result of these declines, the typical black household had just $5,677 in wealth (assets minus debts) in 2009; the typical Hispanic household had $6,325 in wealth; and the typical white household had $113,149.”↵

- For analysis of racial economic divide in the U.S., see annual State of the Dream report by United for a Fair Economy.↵

- John Paul II, Solicitudo Rei Sociales, Encyclical Letter on the Concern of the Church for the Social Order, Vatican Website, December 30, 1987.↵

- The U.N. Food and Agricultural Association reports that “[t]he world produces enough food to feed everyone. World agriculture produces 17 percent more calories per person today than it did thirty years ago, despite a 70 percent population increase. This is enough to provide everyone in the world with at least 2,720 kilocalories (kcal) per person per day (FAO 2002, 9). The principal problem is that many people in the world do not have sufficient land to grow, or income to purchase, enough food.”↵

- See Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World (London: Verso, 2001).↵

- Cited in United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report, 2000 (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 4.↵

- From the Union of Concerned Scientists, citing 2008 data from the Energy Information Agency (Department of Energy). http://www.ucsusa.org/global_warming/science_and_impacts/ science/each-countrys-share-of-co2.html.↵

- While China has risen to be one of the highest greenhouse gas producing nations, with a carbon footprint surpassing that of the U.S., it remains far behind in terms of carbon footprint per capita. Nor does it have the U.S. and Europe's two-hundred-year history of emissions.↵

- United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report 2007: Fighting Climate Change: Human Solidarity in a Divided World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 3.↵

- United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice, “Toxic Wastes and Race: A National Report on the Racial and Socio-Economic Characteristics of Communities with Hazardous Waste Sites,” 1987.↵

- A 2009 study tracking toxic pollutants from American industry and companies found that communities composed largely of people of color or economically poor people suffer disproportionally from industrially generated air pollution having both cancerous and noncancerous health impacts. Produced by Political Economy Research Institute and the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity at University of Southern California. “Justice in the Air: Tracking Toxic Pollution from America's Industries and Companies to Our States, Cities, and Neighborhoods.”↵

- Daniel Fabor and Deborah McCarthy, “Neoliberalism, Globalization, and the Struggle for Ecological Democracy: Linking Sustainability and Environmental Justice,” in Julian Agyeman, Robert Bullard, and Bob Evans, eds., Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 54.↵

- Ibid., 1–2.↵

- For overview of the environmental justice movement in the United States, see Robert Bullard, ed., Quest for Environmental Justice: Human Rights and the Politics of Pollution (Sierra Club, 2005). For an introduction to environmental justice on the global level, see Agyeman et al., Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World.↵

- See chapter 8. See also Duncan McLaren, “Environmental Space, Equity, and the Ecological Debt,” in Agyeman et al., 19–37.↵

- Pogge, “Priorities of Global Justice,” 15.↵

- Larry Rasmussen, Earth Community Earth Ethics (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1996).↵

- Janet Abramowitz, “Putting a Value on Nature’s ‘Free’ Services,” World Watch Magazine 11 (Jan./Feb. 1998): 1, 14–15.↵

- “Parts per million” refers to the ratio of carbon dioxide molecules to all molecules in the atmosphere.↵

- Historically, the question has been: Can capitalism as we know it change substantively? The question no longer pertains, because capitalism as we know it cannot not change. The question has become, “In what direction? And by whose directions?”↵