BY THE TIME Edwyn and I became good friends again in 1983, he was something of a pop star, although his band had been reduced to a nucleus of him and a drummer, Zeke Manyika. The signs weren’t good. I was still working in a theatre as a house manager, something I’d done for years, both in Glasgow and London. I’d bumped into Edwyn from time to time over the intervening period, and followed the band’s fortunes, but we really only became very friendly when he moved into my old house with the two photographers who had always lived there, and I was in my newly renovated, one-bedroom flat down the road in Kensal Green. For me, this was a thrilling time. After about ten house moves and millions of flatmates, I was finally on my own. I had been a member of a housing co-operative since I first came to London and it had finally provided me with my own place. Edwyn was a regular visitor and I became his confidante. I’d listen to his love life complications, feigning concern, while secretly finding his tribulations ridiculously adolescent. But on other subjects, he was a fascinating, instructive and hilarious companion. He had an interesting angle on everything and I learned so much from him.

In early 1984, Edwyn and Orange Juice were without a manager and he asked me if I wanted the job. Of course, I wasn’t remotely qualified for the position, but the thought of self-employment was very appealing and I accepted. I think he may have been regretting his decision even as he was offering, but I gave him no opportunity to change his mind; after years of easy friendship Edwyn had developed a fancy for me and this was actually the true motivation for the job offer. He denied it for years, but I finally got him to admit his weakness. I hadn’t set my cap at him, pop star or no. I was dimly aware that this might have been at the back of his mind, but I was happy to let events unfold as they may. I didn’t see Edwyn and myself in that light. If it became a problem I assumed I’d get the sack. But I was deluded enough to think I’d be an excellent manager.

I sped through a crash course in the structure of the business life of Orange Juice, helped mainly by the terrific figure of Paul Rodwell, Edwyn’s lawyer and a true gentleman. He was, sadly, a rose among thorns. It turned out, to my utter astonishment, that the music business was populated by misogynists and sexists. Men that were uncomfortable around women, basically. Coming from my illuminated, egalitarian theatre world, I think I had a skewed idea of the progress the world was making. I have never seen secretaries spoken to in the way they were in record companies. I was quite shocked.

Edwyn introduced me to the personnel at Polydor Records, where he had been representing himself for a short time. He would waltz in wearing a houndstooth overcoat, carrying a brolly and an old-fashioned, battered briefcase.

‘Hello Edwyn! How are you today?’ the girls in the outer office would ask.

‘I’m very well, thank you, my dear, and may I ask what you’ve been doing for my band Orange Juice today?’ Mass giggling all round.

One of the first meetings I attended as Orange Juice’s manager was with a fairly arrogant character who was in charge of international relations. He began to lecture Edwyn about his lack of touring activity abroad. Edwyn wasn’t mad keen on touring in those days, and Zeke was an illegal immigrant, originally from Zimbabwe, who had overstayed his student visa by about six years and who no longer had a passport of any type.

‘The bottom line is, Edwyn, that unless you have a career abroad, you will end up with no career.’

‘Don’t fucking “bottom line” me, pal,’ Edwyn had snarled back. I listened wide eyed as he continued, starting to get more of an idea of what I had got myself into.

It’s amazing to recall how unperturbed I was as the depths of the problems with his record company unfolded. At this time, Edwyn was my job, not my family, and everything was funny. The next few months were like living in a daft sitcom – it was just what you would think being the manager of a pop star would be like. I was woefully inexperienced, but I was learning as I trailed around in the wake of my eccentric teacher. I even began tour managing at the back end of the year. The job of the tour manager is all-encompassing. Advance planning, musicians, crew, venue logistics, PA, lights, transport, hotels, catering, detailed itinerary, budgeting, accounting. Everyone on tour, especially musicians, can be needy and the buck stops with the tour manager. Later, for reasons of economy, I expanded my role to bus driver. I used to tell Edwyn that if we got really desperate, I’d become a long distance lorry driver. I enjoyed it.

I doubt Edwyn would have recommended a career as a driver for me, though. In the first year I worked for him we spent a lot of time together criss-crossing London in the ‘company car’, a second-hand VW Golf. These journeys were hilarious. Edwyn would go into character (my favourite was a Glaswegian hairdresser called ‘Angelo Morocco’) and keep up a running commentary. Probably because I was in fits, we had several bumps and scrapes. My favourite trick was reversing into parked cars.

‘You’ve just hit that car, you know.’

‘That doesn’t count. It’s just a touch. Everybody does that.’

Edwyn took to screaming ‘Touch!!!’ every time I did it after that.

One day I was delivering a lengthy lecture about car drivers and their disregard of motorcyclists. As I was in mid-flow we pulled up at traffic lights alongside a motorbike. The rider began knocking on Edwyn’s passenger window in an agitated fashion, pointing frantically towards the ground. It turned out I’d trapped his leg against the car. Perfect comedy timing.

Back at the record company, Polydor, relations were deteriorating. At one point, in high dudgeon over a perceived lack of interest in his forthcoming album, Edwyn asked me to convene a meeting with the head of the company. This gentleman was a tremendous character, terrifically old school, very courtly, with a penthouse apartment on the top floor of Polydor’s HQ. (He wasn’t long for the job as it turned out as he was soon transferred to a classical division, which I’m sure would have been a happy move.) But Edwyn had a sympathetic relationship with him and I had no trouble setting up the meeting.

I arrived first, and was greeted with great courtesy as AJ (his first name) enquired as to the reason for the meeting. I was able to fill him in a little before Edwyn blew in, fashionably late (his record back then was a whole four hours), tall and resplendent in a 1950s, camel-coloured, double-breasted Prince of Wales check suit with wide lapels and a turquoise sweater, topped off by his mad quiffed hairdo. I blinked at the sight of this vision of loveliness, but AJ rose graciously to meet him and we got right down to business.

‘Now, Edwyn, Grace has been telling me about how aggrieved you’ve been feeling lately.’

‘AJ, I can sum up my feelings in one word.’ Edwyn raised his hand and brought it down on the table as he thundered dramatically, ‘Betrayed!’

Somehow, I maintained my composure. I will never know how.

By the end of November 1984 Edwyn had completed the last of four Orange Juice albums, which he called The Third Album. (More eccentric, or absurdist, behaviour. Or as Polydor would have put it, annoying.) He decided he wanted to advertise it on TV. This was never going to happen. Record companies don’t normally fork out for expensive television advertising even for groups they like and Polydor was no different. But we found a way ourselves. We funded a limited run on Channel 4 at Christmas time and I was cut some very nifty deals. We made the ad ourselves with the help of a Channel 4 Films producer called Sarah Radcliffe, who did it for nothing because she liked Edwyn and is a genuinely brilliant person. We had met her when she produced the last-ever Orange Juice video for a song called ‘What Presence?!’ that was directed by the famous British avant garde film director Derek Jarman. Working with Derek on the video was the greatest pleasure, the most ridiculous fun it is possible to have at work. Later, when I needed some advice about making the advert, I turned to Sarah, and she simply took over. How wonderful. It was directed by Nic and Luc Roeg, sons of the film director, Nicolas Roeg, and consisted of Edwyn holding a large fish, and introducing his new album. Cut to Zeke who intones, seriously: ‘Which includes the flop singles, ‘What Presence?!’ and ‘Lean Period’.’

All this as the word FLOP! flashed up on the screen continuously.

We never imagined it would help sales much. Edwyn was content to throw his own money at an elaborate wind-up of the record company. We were young and foolish and ever so slightly petty, and it had to be done.

So, that was that with Polydor, as you can imagine.

•

THE ENSUING TEN or so years were up and down for Edwyn on the career front. Strangely though, in retrospect, I can barely remember the periods of penury; when I was reluctant to answer the phone or open letters to find what fresh hell lurked inside. All the bad stuff was punctuated by adventure and enormous creativity. That’s what I remember. Hurtling from one daft sketch to another. We invariably managed to find a way to survive each mini crisis, which in turn steels you for the next.

Edwyn moved into my little flat one item at a time. One day I turned around and all his worldly goods were there in their entirety, although I had no recollection of how they had arrived. I had formerly been a proto-minimalist: the fewer possessions, the easier to move, the less to clean up. My new flat had been spacious and empty, but, alas, those days were gone for good. As I surveyed piles of Edwyn’s eclectic stuff, the battle lines for the next twenty years were drawn between the hoarder and the chucker.

I operated from the illustrious surroundings of our living room, conducting all business cross-legged on the floor. There was no room for a desk. If I was out, in order to maintain a semblance of professionalism, or more likely just for naughtiness’ sake, Edwyn would pretend to be my cockney PA, Dave.

‘Grace isn’t available, this is Dave, her assistant. Well, I’m not really orfarised to make those decisions. But I’ll pass it on to the organ grinder when she gets back.’

Later, when callers would revisit their conversations with Dave, I would struggle to hold it together. Eventually I started to behave as if my imaginary PA really existed.

•

NOW A SOLO artist, we struggled to find a record company willing to support him. Edwyn’s music still came as easily and naturally as it ever did, but he had made a fair few enemies in his time and we were up against it. We toured quite a bit, in the UK and around Europe, with me as tour manager and sometime bus driver. I only gave up after our son, William, was born, completing my last tour behind the wheel when I was six months pregnant. But eventually, in 1989, we were able to get Edwyn’s career somewhat back on track when he was invited to record an album for a German label, Werk, at their superbly appointed studios in Cologne. Edwyn relocated to the city for three months, together with various members of his band and old friends, including our friend Roddy Frame, and the Orange Juice producer and famous reggae maestro, Dennis Bovell. These were wonderfully happy days, with Edwyn at his best, collaborating intensely with much-loved fellow musicians, with no animosity or rivalry. The result was just as he had hoped. I drove a transit van from London to Cologne at the end of the process, in order to transport the instruments back. I remember arriving in the dead of night, with Edwyn and Tomgor the producer waiting up, dying to play me the fruits of their labours.

With this quite successful album called Hope and Despair, things started to take a turn for the better.

•

BY 1992, we were still living in my old flat in Kensal Green, still broke, but pretty happy. William had been born in 1990 and I always feel he brought us a lot of luck. Edwyn had begun to produce records for other bands and was hell-bent on acquiring a studio of his own. This was the only way he would be free to make records, without having to go cap in hand to a record company for permission to do so. We reckoned that the law of diminishing returns had come into effect as far as the record business advancing Edwyn money was concerned. With each approach to the powers that be, there seemed to be increasing reluctance to involve themselves with Edwyn’s recording career. In short, we couldn’t get arrested, and we were quite weary of the dance. I was thirty-four years old, Edwyn thirty-two, and it didn’t seem very dignified at our time of life to go begging to idiots for the right to record. We were great at doing things on a shoestring, had had lots of practise in recent years, and were determined to find a way to plough our own furrow, unencumbered by the expectations of what Edwyn used to sarkily refer to as ‘The Industry of Human Happiness’.

Bit by bit, Edwyn had been acquiring pieces of vintage recording equipment, centred around a Neve console, or mixing desk, from 1969 (with the famous 1064 and 1073 modules – he’s always bragging about them), picked up for a song from the defunct Goldcrest Film Studios in London’s Soho. As tedious as it may sound to outsiders, acquiring and learning about this old gear had virtually become the Meaning of Life to Edwyn. Next to his baby son, that is.

A vintage equipment dealer and producer named Mark Thompson, whom Edwyn met in 1993, had helped him find the adored mixing desk. Together they set up home in a converted coach house at Alexandra Palace, pooling equipment and splitting the rent. The birthing process was long and fraught and, for us, set against a financial background that was, frankly, farcical. Looking back, I have no clue how we survived this period of keeping the studio going, and living on thin air. I do recall doing the sums at one stage and Edwyn asking me how much longer we could survive. ‘Until two months ago. Press on.’

•

A RECORDING STUDIO is a complicated technical environment which requires very specific specialist skills to put together. At its hub is a recording console, or desk, which receives the music from the microphones, treats it, colours it, manipulates it, with the help of umpteen other bits of gear we call ‘outboard’, and transfers it to tape. Or that’s how it used to work. Nowadays it will go to a computer hard drive. (Edwyn still swears by tape). The specialist guys who cable this lot together are, in my experience, a strange bunch who inhabit a parallel universe and are impossible to tie down to budgets or timescales. But where there is a will there is a way. And when it all comes together, you need a gifted engineer to operate it.

And this was when the beautiful thing that is Sebastian Lewsley came into Edwyn’s life. They had met a year or so back, when Edwyn spent time at a studio in Chiswick called Sonnet. Seb was nineteen and the studio owner had been ruthlessly exploiting his youth, enthusiasm and talent, although Seb did learn a lot in the process. It was a very funny place, frequented by old lags of the music industry, such as Shakin’ Stevens, the bloke from Sailor, and the brilliant Anthony Newley, providing Seb with a rich seam of comedy that he mines to this day. Edwyn and Seb are wont to slip into character, as Jackson Gold and Denny Lorimar, two old-school music producers, bitter old dinosaurs, boring for Britain. This pair, based as they are on real-life weirdos that have been part of Edwyn and Seb’s past, have made an indelible impression on every client who has passed through our studio in the last fourteen years or so. Nobody escapes; all are sucked into the sad world of Jackson and Denny. People have come to speak of them as if they really exist.

In 1999, Channel 4 commissioned a sit-com based on the pair’s imagined exploits. Six episodes and a one-hour special were made. The storylines, risible as they were, were sketched out in advance, but the dialogue was entirely improvised. A huge cast of characters, composed entirely of friends and colleagues, (for example, Jamal, our accountant, played Jamal, the accountant) rose magnificently to the challenge. It aired late at night, and was re-run, garnering Jackson and Denny a tiny but fanatical following. One day soon, it will resurface.

Edwyn asked Seb to leave Sonnet behind to come and join him, and they learned the new studio together. Ever since then Edwyn has spent much more of his waking, working life with Seb than he has with me. They have learned to communicate telepathically which, in the circumstances, has proven to be handy.

The arrangement at the first studio was a six-week-turnaround type of thing. In early 1994, the studio was finally ready and Edwyn spent the first six weeks producing an album for a band called the Rockingbirds, which would finance the next few months and allow him to work on his own album when it was his turn to use the studio.

Finally, in May, recording got under way. The whole thing took six weeks from start to finish, with no remixes. One particular track was recorded in two days. Very easy, according to Edwyn, and not bad for the song that made us our fortune, changed our lives and continues to support us to this day. The song was called ‘A Girl Like You’, and it’s much more famous than Edwyn. In America, loads of people think it was a David Bowie record, or an Iggy Pop record. I’m not sure why but it’s true.

The track was recorded, written and produced by Edwyn. Two of his heroes and dear friends, Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols and Vic Godard of the Subway Sect, played on it, as did Clare Kenny and Sean Read. All brilliant musicians, and also the very first pick you would make for fantastic people to share a session with.

Edwyn has been incredibly fortunate to have the song’s protection at his back through the most challenging years I hope we’ll ever have to face. How lucky it is to have resources to ensure that whatever he needs, he gets. And I have not had to give up my job to look after him. He is my job. We are acutely aware that most people who find themselves in similar circumstances don’t have our options. They have to take what’s on offer and that, I’m afraid, is pretty much a lottery (but even at its best, it’s often rubbish).

Did Edwyn have a glimmer that lurking on this album was a track that would turn his life around? Not at all. We did think it sounded like a potential single, but a hit? We had thought lots of his previous singles were potential hits but we had proved to be all too wrong. In our minds, unless you had a fairly souped-up industry engine on your side, your chances were less than slim.

As it turned out, we were almost right.

At the end of the recording sessions for the album, called Gorgeous George, Mark announced that he wanted the studio to himself and had negotiated a new lease with the landlady, so we were immediately out on our ear. No bad thing as it transpired, because life was about to become so frenetic that the additional burden of running the studio wouldn’t have helped. So, Edwyn completed the recording of his album and the very next day we moved the equipment out. This is always a ghastly process, even though I am an accomplished removals expert. By necessity, certainly not by choice. I loathe it. Once more we turned to our trusty removers, my neighbour, Big Phil, and his sidekick, Mad Tony. They called the business (assets: one transit van) Caledonian Removals, and they had the best business card in the world. Under the company name was their motto:

‘We Don’t Fuck About.’

Which they did, actually, quite a lot. Top quality.

The gear went into storage and we set about finding a release for the record.

We licensed the record for the UK and a couple of other territories to a tiny independent label called Setanta, run from a squat in Camberwell, south London, by a Dubliner called Keith Cullen. This would be a real collaborative effort, as the label was even less experienced than we, and we were all ill-equipped to deal with the juggernaut of ‘A Girl Like You’.

The record was released as a single in November 1994 and entered the chart at no 43, I think. Or 45. Anyway, not a hit. Business as usual, we thought. So near and yet so far. Oh well. But then an odd thing happened. It wouldn’t go away. As the year drew to a close, the track was getting increasingly more airplay and we received news of radio stations picking up on it in Europe and Australia – countries where it had not yet been released – so, airplay in countries where we had no record company yet. Something was up, and it had nothing to do with my business acumen.

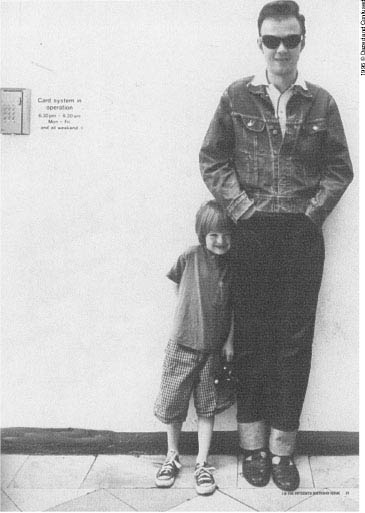

In late February 1995 we travelled to Australia for a twelve day promotional blitz to support the increasing success of ‘A Girl Like You’. I don’t recommend this journey. Australia is too far away to go for anything less than a month. I have never known jet lag like it, akin to a bad flu. Edwyn worked extremely hard, performing five shows with a band of musicians assembled for him by the record company (great guys who were perfectly rehearsed when we got there) and doing about a hundred interviews. William, aged four, coped far better than we did. When sleep overcame him, he just dropped wherever he was. I would bring pillows from the hotel and make a nest for him in the dressing rooms, where he would snooze happily, undisturbed by the cacophony going on around him.

On the way home we parted company with Edwyn at Hong Kong airport. He was to fly on to Los Angeles while we returned to London. We would join him in Austin, Texas, five days later. This was Edwyn’s first ever trip to the US. In LA, he was scheduled to perform acoustically three days later at the famous Viper Room, once co-owned by Johnny Depp. On his arrival, he decided to go down there to check it out. Combining a few drinks with his jet lag and travel weariness, he sat at the bar. When a couple of girls started chatting to him, he responded, charming them with his delightful Scottish accent. Their boyfriends, a couple of muscly jock types, weren’t so charmed and let him know it. I don’t know what he said back but I believe it involved some old-fashioned Glasgow-style cursing, and moments later he was on the floor, felled by a blow to the face. He had only been in America for three hours and he’d managed to get into a fight. In the Viper Room. When he called me later that night, feeling very sorry for himself, his two black eyes were already developing nicely.

The next day he met up with an old friend of mine, Neil Fraser, who had married an LA girl and become a California lawyer. Neil planned to take Edwyn guitar shopping at a market in Pasadena. They stopped off at his home first and as he was reversing the car down the driveway they both felt the back wheel crunch over something. Neil had run over Bingo, the family dog. A quick dash to the vet later and poor Bingo had to be put to sleep. Edwyn watched awkwardly as Neil broke the news to his two small daughters who, although initially distraught, rallied at the thought of a replacement for Bingo.

‘We want a Chihuahua! We want a Chihuahua!’

When I received the call updating me on Day Two, I started to panic about Day Three. I begged him to stay in his room until the show. Will and I met him two days later at the airport in Austin and got our first look at his impressive shiners. They were still in evidence when we reached New York a few days later. He performed his acoustic set in three locations, allowing some of his small but devoted band of American supporters to see him play for the first time. In New York Edwyn’s favourite aunt, Kate Mackintosh (who had lived there for twenty-odd years), was our guest of honour. She had never seen him perform before and was mesmerized both by Edwyn’s stage persona and the audience reaction (‘Wee Eddie, is that really him?’). These memorable shows were enhanced by his hysterically funny and rambling rendition of his LA adventures. He took to the stage wearing dark glasses which required explanation. Revealing the damage created a dramatic flourish.

By summertime 1995, we had a huge record on our hands. It was never a case of thinking of ways to make it happen, more of running to try and catch up with the damn thing. A phenomenon, a record with a life entirely of its own.

In May I had asked my sister Hazel to pack in her job as a nursery manager and come and work with me. We had become a proper family business. I’d moved from my office of the last eleven years, the aforementioned living room floor, into a little serviced office in Queens Park, where we had the luxury of two telephone lines and a fax machine. Edwyn was more or less constantly away on tour or on promotional duty and I was so crazily busy I couldn’t think straight. The fact that we owned the record outright was in many ways a brilliant thing, especially financially, but day-to-day it was a logistical nightmare, as it was being managed by the world’s least-organised woman and her very organised but new to the game wee sister. I would sometimes turn to Hazel and see a look of disbelieving panic on her face. The phone never stopped ringing, whether in the office or back at the flat. We had licensed the record around the world, about eight deals in all, but we were the hub.

Our licensees would enthuse about the convenience of being able to call one number for the answer to all questions, rather than the usual layers of departments, but for Hazel and me, it was intensive stuff. At four o’clock, I would pick Will up from school and the little soul would have to amuse himself in our cramped office for a few hours until I could finally get him out of there, feed him something unsuitable, bath him, get him to bed and then get back on the phone to overseas time zones. As a naturally slothful person, this frenetic level of activity was a shock to my system.

I would also travel a lot with Edwyn, sometimes leaving William with Hazel and her partner Mark, but often taking him with me, in a way that would most definitely draw stern disapproval from the school authorities nowadays. But back then they were more relaxed and didn’t argue with my theories about adventure and learning by experience, in spite of the obvious flimsiness of my excuses. But as far as we were concerned, William simply had to come with us; we would have missed him too much. He was a tremendously easy-going traveller, coping with jet lag much better than I and taking the harum-scarum schedule in his stride. Before he was seven he had been in all corners of the globe, but at that age I really think he believed that this was what everyone’s dad did. I used to call him our icebreaker, as he bowled across the world, charming everyone who crossed his path. I’m sure he wishes he could repeat the adventure now he’s grown up and that it was rather wasted on him as such a young kid.

•

EDWYN COPED MANFULLY with every piece of lunacy that real success throws at you, something we weren’t accustomed to. We were no longer young or stupid or gullible, but it was still impossible to avoid completely mad sketches wherever you went.

I have a video of Edwyn in Athens, on Greece’s most-watched TV show, an epic affair that ran for three hours of unremitting tackiness on a Sunday night. He managed to restrain the producer’s determination to drape him in dancing women whilst he mimed to ‘A Girl Like You’, and kept at least a few feet between him and these scantily clad lovelies. However, he then re-appears to do his second number. Here, he strokes his chin quizzically as the fabulously pneumatic, blonde presenter delivers a long-winded, eyelash-batting introduction to camera. She is a gorgeous, sexy thing wearing a gold lamé dress and holding a golden gun, which turns out to be a fag lighter, 70s-style. Eventually she turns to Edwyn, leans on his shoulder and purrs: ‘Edwyn … you light my fire …’ and activates the fag lighter. At which Edwyn pulls a saucy face, Frankie Howerd style, nods and replies: ‘Thanks very much!’ Cue the music!

In Belgium, Edwyn appeared on the Flemish version of Top of the Pops, at number two in the charts. At number one was the country’s favourite comedian, dressed up as a tree, singing a charming number about arborophilia, or tree fucking, as it is more commonly known. There really is such a thing, but in those pre-internet days, it was a pastime only popular in the Low Countries.

On arrival in the Philippines in the spring of 1996, the three of us were greeted by a phalanx of television cameras and microphones. They all walked backwards down the corridor to Arrivals, filming us as if we were Mick and Bianca Jagger in the 70s, except I’d just spilled a glass of champagne into my lap on the plane and looked like I’d wet myself. We were whisked through the diplomatic channel to a press conference where I annoyed our host, Bella Tan, record company supremo, Manila’s top female gangster and genuine old mate of Imelda Marcos, by politely refusing to sit at the top table. (I’m the manager, not the attention seeker … well, not in these circumstances anyway.) We were on the front page of the national paper the next day. Edwyn did eight TV shows in two days, where he was backed by a boy band, who wore trendy sports clothes and danced like N’Sync. Apparently, in the absence of Edwyn, these boys had been dancing to ‘A Girl Like You’ on every media outlet for months and the population strongly associated it with them. They were called The Universal Dancers, six of them, including my special favourites, the sixteen-year-old twins, James and Jim. Everywhere he went, Edwyn saw cash being exchanged in a blatant way. Old fashioned payola for TV and radio exposure was alive and well in Manila. We were warned to keep a close eye on William, on account of the local craze for kidnapping the children of people in the public eye and holding them for ransom. We’d only been there two days and I couldn’t wait to leave.

At the end of this whirlwind tour, having fulfilled their requirements, we were unceremoniously dumped in the car park at the airport by one of our host’s scar-faced honchos. Lovely. This is a country of some 95 million people and all of them watch TV like maniacs. Edwyn was a celebrity in the airport and on the plane out of there. But this was celebrity of the flimsiest variety. I guarantee if we’d gone back the following week, they would have had no clue as to who we were.

•

HALF WAY THROUGH 1996, and after almost two years of non-stop running, I decided that this last promotional tour of the Far East, encompassing nuttiness of every hue in Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia and last but not least, the delightful Philippines, should bring to an end the story of the crazy, wonderful record. I don’t think either of us was cut out for the pop star lifestyle. We were so tired. I kept wondering how the properly famous do it. To keep going, they must really love and need the attention. No amount of attendant luxury could make up for the tyranny of the schedule or the inanity of the promotional and publicity activity. For us, this stuff was only bearable in small doses. I knew we would enjoy it all as hilarious memories and anecdotes, but I was so glad it was winding down. With our track record, I reckoned it was something we wouldn’t be repeating any time soon.

•

EDWYN COULDN’T WAIT to get off the promo bus and back to the quiet of life in the studio. Seb had found our new studio, West Heath Studios in West Hampstead, in mid-1995. A beautiful old stabling block originally used for the Fire Brigade horses, it had been turned into a recording studio by a group of guys in the early 80s, one of whom was Alan Parsons, the Abbey Road engineer who recorded Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. It was the place of our dreams and we’re still there. Hazel and I have our office there and Will feels as if he grew up in this building, as it was the place he’d come to when I picked him up from school each day.

My housekeeping has always been the laughing stock of all my friends, and by early1996 things were truly falling apart – my laundry system in particular. This consisted of two giant piles on the kitchen floor. Clean pile and dirty pile. Will was fond of curling up for a nap in the clean pile. It got to the stage where I was too embarrassed to let the man in to read the meter. I had decided that between mad amounts of work, looking after Will and house cleaning something had to give, and skivvying it was. Edwyn would for years regale strangers with the hilarious story of how he set off on a tour of the US, leaving behind a half-drunk can of Red Stripe by his side of the bed. Apparently when he returned twelve weeks later it was still there. I’m sure he’s right; I certainly didn’t notice. In any case, I countered, it was he who had left it there, not me.

Around this time, Edwyn did an interview for Q, the major UK music magazine, where the journalist comes round, sits in your living room and checks out your record collection. I did tidy up for them, but nonetheless they were to write: ‘Pop star Edwyn Collins lives in a hovel in Kensal Rise.’ Very cheeky. In any case, my reasoning was that if I got my head down and concentrated on the work in hand, perhaps we would soon find an escape route from the ‘hovel’. And so it proved to be.

•

IN JUNE 1996 we bought our house in Kilburn. It had been languishing on the market for a year because, in the language of the estate agent, it required extensive renovation. The roof was knackered, the plaster on the walls was soft and crumbly, there was evidence of dry rot and some of the ceilings were bulging downwards in a threatening manner. Obviously, the house for us.

Six months of home improvement drama later, we moved in, leaving behind the little flat I had called home for thirteen years. Since we had already acquired the studio, all of Edwyn’s gear and most of his general junk had been moved there, allowing us to move into our new home with hardly any stuff. Three floors of virtual emptiness. On our first night there, we rattled around, three fish out of water. Will, aged six, was aware that he would finally have a bedroom to himself and had been excited about planning it. He had a brilliant platform bed, constructed by Pav, our good mate who had been the project manager on the rebuild. In the end, though, the actuality of sleeping in his own room, with us not only in a different room, but on a different floor, proved too much for Will, a child who had been used to having a parent within stretching distance his whole life: ‘I hate this GREAT, BIG, WANKER HOUSE!’ he sobbed. ‘What you need are SMALL, LITTLE HOUSES!’

•

IN FEBRUARY 2005, Edwyn turned forty-five years old, an elder statesman in music now. He was in an untroubled place in his career. He was still recording, but without pressure to hit the heights. For the last ten years he and Seb had been established at their studios in West Hampstead, where they had carved out a reputation for themselves and the studio as a unique environment to make records in. They had augmented the equipment there with an ever-expanding collection of vintage recording effects and microphones. They were both totally wedded to the place. At his ease, Edwyn had just completed the recording of a set of songs for a new album, a record which reflected his powers as an accomplished songwriter of huge experience. Edwyn was a sharp self-editor and his quality control was rigorous. This was a fine record and he was looking forward to moving to the mixing stage. Life was busy.

At home I was unaware of any serious signs of trouble on the horizon. Edwyn and I had been together for just over twenty years. I had been his manager for about a year longer than we had been a couple. William was happily approaching his fifteenth birthday, growing up bonkers, but in a very loveable way.

I was semi-aware of a certain irritability about Edwyn, a slight tendency towards increasing grumpiness. I also knew that he was having headaches. This we both put down to an increase in his drinking. He was always a rubbish drinker, what our friend and Edwyn’s former guitar player Steve Skinner, a Yorkshireman, called a ‘one-pot screamer’. It didn’t suit Edwyn; he couldn’t handle it, and he seemed to go from totally sober to dead drunk in the space of about five minutes. So I thought I knew what the trouble was. Go easy on the drink. But Edwyn won’t be told. So he swallowed the Solpadeine and carried on.

Only in recent times has Edwyn revealed to me the extent of his anxieties at that time. He may have seen the storm clouds gathering. In an interview lately he described: ‘a sense of foreboding, a sense of agitation’. I also had no clue as to the extent of the pain he was suffering. He had not been to see a doctor in over a decade and now his fear prevented him from doing so, or even telling me how bad he felt. Apparently he had a dread of discovering the cause of the pain. For me this knowledge comes – too late – as shafts of pure guilt. My fault, my job to read the signs, to protect my family.

But none of the signs were sufficient to register a warning of the cataclysm to come. And so life moved stealthily forward towards the unavoidable.