THE REALISATION THAT reading was lost to Edwyn had come to me quite early on, before Trudi had arrived on the scene. Prior to his illness, Edwyn had been working in conjunction with a label called Domino on a very smart release of the earliest Orange Juice recordings called The Glasgow School, after the art movement of the same name. The record was due out in March 2005 and the label wondered if they could still go ahead? I immediately assented as I had no doubt Edwyn would want me to. I brought in a magazine with a long article covering the release, including the last interview with him before his haemorrhages, and showed it to him. His eyes scanned the words uncomprehendingly. He began turning the pages, quickly, unseeingly, clearly troubled. Nobody had prepared me for this and, crazily, in those early days I had never made the link between speech, reading and writing. So this was the moment I experienced the realisation that Edwyn, who loved Lermontov, Goncharov, Zamyatin, Fitzgerald, Brautigan and Salinger, could no longer read. It came to me like a blow to the solar plexus. And I had to hide my shock because I could see the fear in his eyes. To reassure him, whilst desperately trying to mask my own reaction, I had said: ‘A step at a time, Edwyn, we’ll get it back.’

Almost six months later, he hadn’t forgotten my promise.

‘You want to learn to read again, Edwyn?’

‘Yes, help me.’

‘We’ll have to start at the beginning, with children’s books. You don’t mind?’

‘Not at all.’

The speech and language therapy he received in the rehab unit involved very little structured reading recovery, mainly because it is so time-consuming that nothing else would get done in the short periods allocated in the course of the week. We had done a little practise, using newspaper headlines and other pieces of bold print, but while he was in hospital it was hard for us to properly structure a reading recovery programme. Edwyn realised the time had come.

•

AND SO, FINALLY, he was home. We cracked a bottle of champagne with Andy, Susan and Nan. Afterwards, Edwyn had his usual early night, safe in the knowledge that this time there would be no return to the strange and horrible existence of hospital.

It must seem so ungrateful to be so desperately glad to be shot of both hospitals. They saved his life and got him walking again. But a very nice sister on the RRU summed it up. Asking her if they often got the chance to see what became of their patients further down the line, she answered, ‘Sometimes, but not as often as you would think. For some of our patients, this place represents the worst time in their lives. They’re not in a hurry to revisit those days. Understandably.’

Edwyn fell into this category of patient, for sure.

•

EDWYN’S FIRST SHOWER at home was interesting. Nan and I attacked the unfortunate man in a pincer movement as we attempted to give him his first proper experience of the newly fitted-out bathroom. Up until now, I’d gone for the easier option of a strip wash on our weekend visits home. The logistics of showering were not straightforward. Small room, awkward angles, two chairs, and transferring him up a step from the wheelchair to the special showering chair. Nan and I wound up in hysterics, shouting ludicrous instructions at each other, (‘forward momentum!’), although I’m not sure Edwyn found our performance so hilarious. It was like having Laurel and Hardy give you a shower. But the first attempt is always the worst. By the first Sunday morning home, we had refined the technique and built in moves that one person could manage. Edwyn gains in confidence the more times a move is executed so that he assists too, making the whole process much less tortuous. So now he had the luxury of a daily shower in his own new bathroom. So different from the hospital facilities, which had given me the creeps.

Edwyn has called me a hotel snob, going all the way back to our touring days in the 1980s, when we could sometimes only afford the most basic places. I hated it. I recall guest houses where it was advisable not to put your bare feet anywhere on the floor. He never minded much, having done many ‘nylon sheet’ tours in the early Orange Juice days, but when we graduated up the scale I was very relieved. The nouveau riche in me does love a nice hotel, I admit. When Edwyn was away without me and we would talk on the phone I’d say, ‘How’s the hotel?’

‘Well, not bad, but not exactly a Grace hotel.’

Or, ‘Very much a Grace hotel.’

He has kept this mockery up for years. So, closeted together in the grotty bathrooms of the RRU, I’d mutter, ‘Definitely not a Grace hotel …’

•

BACK AT THE RRU, Edwyn had three days of therapy sessions to complete and another dose of Botox. On Wednesday, after lunch, when the unit was quiet, we slipped unceremoniously out of the back door. From now on we really were on our own. Edwyn had a final quote that I recorded in my diary.

‘Help me, please, discover what I am.’

‘Okey-dokey, Edwyn, I shall!’

•

IN THE COMING months and years there would be many times when the hugeness of what had happened to us would hit me with such force that I would be rooted to the spot. I would be daunted and scared at the thought of the future. I would yearn so much for things to go back to how they had been. The changes in Edwyn were, and still are, profound, and sometimes I would feel as if I were in mourning for his old self. Sometimes this would translate into behaviour that I’m ashamed of. I have often been short-tempered, impatient, nagging. But it would be Edwyn who would rescue me from the worst excesses of bad temper, from dark, despairing thoughts. Once free of hospital, his mood completely lifted and, although there would be moments of frustration and annoyance aplenty, he has never succumbed to despair or bitterness. His remarkable self-belief, initially only a glimmer, would soon grow to a bright flame, and would carry us both forward. That and the wonderful backing of family, friends and top-notch therapists.

The progress that Edwyn was set to make over the next few months would be so dramatic it led me to muse on the powerful force that home was exerting on his neurological functions. Maybe he had been right after all. Should I have brought him out of hospital earlier? Who knows. I was excited and grateful to see that he was lapping up what had quickly turned into a frenetically busy schedule like a man possessed. Our community occupational therapist (we had one for a while) was concerned that I was setting too strong a pace, but I was being led by Edwyn. The idea that he could be made to do anything that he was not in accord with was laughable. When he was tired, he told me so, and we rested. But his drive, to my joy, was formidable.

•

PLANS FOR THE future were afoot. It was time to get the sleeves rolled up.

We would now be reunited with Trudi. She would soon be up-to-speed on the progress Edwyn had made with Pip, and ready to make plans for the big push. (Note the royal we. Every now and again Edwyn will say to me, when he considers I’m unduly harsh or insensitive, ‘I’ve had a stroke you know!’

After the first few times I began to counter with, ‘Yep, and I had it right alongside you, dear.’ This is unfair, but he knows what I mean.)

I had also planned our next physio move. A practice called Heads Up! (the exclamation mark is important) appeared to be a solitary island of neurophysiotherapy, a very particular specialty, in an otherwise vast desert of nothingness in the south east. Their nearest outpost was at Park-side hospital in Wimbledon, a good hour and a half drive from us. But that was fine. I had lined up an appointment for a week later with the physio there, Ellen MacDonald. This was to be a hugely significant meeting.

On a warm Friday in August, we drove across the Thames to the hospital, which bordered Wimbledon Common, to meet Ellen for the first time. I was laden with all my RRU tackle, like a good student wishing to make the right first impression. There were various arm splints, leg splints, shoulder slings, the quad stick, and even a piece of headgear – a slab of moulded white plastic with straps fastening under the chin which had been made to protect the space in Edwyn’s head while he did his physiotherapy. Apparently he was submissive about this while he was in hospital, but I could never get him to agree to wear it with me. Point blank refusal. It offended his vanity.

We sailed in, Edwyn in the wheelchair and me carrying my enormous kit bag. Ellen sized us up while we took her in too. She was Australian, late twenties, slightly built but strong looking. She had a no-nonsense personality which took about two minutes to identify. She would later tell me that she had to hide a smile when she looked at us laden down. She had worked at the RRU for a while and recognised the signs. Her assessment of Edwyn’s physicality began immediately. Shoes and socks off, shirt off so she could observe his entire torso (he always wore shorts for physio from here on), and out of the chair. Edwyn could walk, supported on one side by his quad stick and on the other by a person. From now on, as well as building up his tolerance, it would be all about the quality of his walking. Edwyn, quite naturally, was overcompensating on his left side for the things he could not do on the right. But it was important to combat this left-side leaning, which did all sorts of mad things to his upper body, to build confidence that he could use his right side, even if the feedback he was getting from every area there was minimal.

This would not happen overnight. The work was intensive, gruelling and repetitive, and the gains came slowly, with some spectacular exceptions. In consultation with Ellen, and in order that Edwyn would get maximum benefit, we agreed on three sessions a week. Apart from his resting arm splint, which he wore overnight to reduce spasticity in his hand and arm, Ellen was not keen on continuing use with the rest of the kit. Edwyn was given a normal walking stick. She also recommended a very clever gizmo that we use to this day, to help combat foot drop.

I believe it was on our third visit to see Ellen that we had a conversation about what goals Edwyn would like to aim for in the short term, his priorities. Edwyn, as he often did then when asked these questions, looked at me. I had no hesitation. Stairs. Just a few stairs, two even, would make all the difference in the world. We could get in the front door without the wheelchair and the ramp, and that would be a very big deal.

‘You haven’t tried stairs yet, Edwyn?’ Ellen seemed slightly surprised. ‘OK, let’s do it.’

Before he could even think about it we were in the corridor and Edwyn was mounting a flight of stairs, holding on to the railing on the left, and leading with his left foot on each tread, while Ellen gently assisted the placement of the right foot. A whole flight, just like that. I stood open-mouthed. How was he going to get back down? Just the same as he got up, except that on the way down, the right foot was placed first and then the left followed, having taken the strain. Clever, clever. Ellen’s expertise allowed Edwyn to follow her instructions with total trust. I was hopping up and down with glee. My next question came fast. How soon could we try this at home? Very soon. We’d give it a couple more sessions and then Ellen would give me the all-clear to have the stair lift taken out. I would need an additional rail installed, so we had one on either side, and some outside ones too, but goodness me, I hadn’t dared hope to be rid of it this soon. I have never been so glad to have had poor value for money from a purchase! (In fact, the stair lift company take them back and even give you a bit of a refund.)

So this was the beginning of Edwyn’s partnership with Ellen. As a working team, they suited each other perfectly. Neither suffered fools gladly, both were outspoken and both were hard workers. In Edwyn’s case, almost all the time. He had his moments. I recall Ellen working hard on his foot one day, when Edwyn interrupted with a lengthy, disjointed soliloquy about how difficult it was for him, how deserving of understanding he was; really giving her the old sob story. She stood, holding his foot in the air, looking at him quizzically, eyebrow raised. When he was done she said, briskly, ‘Finished? Right, back to this foot.’

Edwyn liked that. ‘Ellen, you’re awful. But I like you!’

Most of the time, he was putty in her hands.

•

SAD TO SAY, the same could not be said of his attitude to me. My notebooks are crammed full of exercises we were encouraged to follow through on at home. I was so anxious about progressing, about not sliding backwards, about getting it right. But Edwyn simply hated doing exercises with me. Attempts at gaining his co-operation on physical jerks was to cause more friction between us than any other single issue. The psychology just didn’t work very well. Edwyn was extremely resistant to me telling him how to do things. I suspect that if I could see a replay of my coaching style I would hate me as well. I’m sure I said, ‘You do want to get better, don’t you?’ a few times. I may have come over a teensy bit patronising occasionally, as well.

When we discussed the problem with Ellen he would simply say, ‘Grace is terrible. Oh, terrible.’

If I’d ever tried to teach him to drive, which I hadn’t, because he had no interest in learning, I suppose I would have realised how tricky it was going to be as his mobility coach. Even now, when I try to explain to him how much better off he would be by adopting a policy of blanket submission, accepting that I know best in all matters, he will have none of it. Strange.

•

BUT NO MATTER, Ellen was doing an extraordinary job, I did my best, and we pushed ahead. Towards the end of August, my friend Pav and the stair lift company dovetailed with another so that the lift could go and the rails could be installed, all on the same day. In the afternoon, when Pav had finished, he joined us in the back garden and asked if Edwyn wanted to try a climb. There are thirty-seven stairs from the ground floor to the top, where our bedroom is. Edwyn climbed them all, without a pause, three weeks after coming home from hospital. He could now place his right foot without assistance. For a while, I would follow behind, for safety. Slowly, with some adjustment, but independently. And then, at the summit, having had a tour around our bedroom and bathroom for the first time since February, he descended in one take. Now he could sleep in his real bed, beside me, whether he liked it or not.

•

AROUND THE SAME time, now early September, we left the wheelchair in the car park and walked the short distance to the physio block and into Ellen’s treatment gym, without mishap. Then, one night soon after, we had dinner in a local restaurant on Kilburn High Road and decided to walk home. It was a walk of about a quarter of a mile. A virtual marathon. I promised Edwyn he could have as many rest stops as he needed. I knew there were a series of walls on the way that we could flop down on if need be. But he didn’t stop to rest once. I was still holding his arm at this time, gently supporting him on the right side, but he was doing all the hard work. After that, I folded the wheelchair up and put it in the studio store room. We’ve not used it since. Even at airports we decline assistance, which would mean sitting in a chair. The staff look at me like I’m barking mad sometimes and Edwyn wavers a little at the thought of miles of corridors. But it’s a good workout; we leave ourselves plenty of extra time and he gets stronger.

I have no phobia of wheelchairs or their users, quite the reverse. I have lost the hesitancy of the able-bodied around the wheelchair-user. I have a much better understanding now of what is involved. It’s just that, having come so far, I can’t bear to contemplate any step backwards. We must always be going forwards. What a tyrant I am.

•

DURING THIS MAGICAL first month at home there were to be two more red-letter days.

The first was Edwyn’s forty-sixth birthday, on 23 August. What should we do? Edwyn was never one for a fuss about birthdays, but this was special. So, I booked a table at the Savoy Grill, in the art deco splendour of the Savoy Hotel, to enjoy Marcus Wareing’s great food. We were a party of eight: Nan and Will, Andy and Susan, Pav and Henri, Edwyn and I. All of us beautifully suited and booted, we gathered in the American Bar to toast Edwyn. We toasted him several times that lovely evening. The food was gorgeous, the welcome was warm, the company perfect. Is it possible to have more to celebrate? I was blissfully happy, with my family, with my friends, with Edwyn. Writing now, I can conjure up the feeling, heart full. As we waited in the foyer for the taxis home, I saw Will having a right old chinwag with the commissionaire. As he helped us into the cabs, the gentleman complimented me on my son’s lovely manners. That just about finished me. Back home, Edwyn couldn’t believe he’d made it past midnight without flagging.

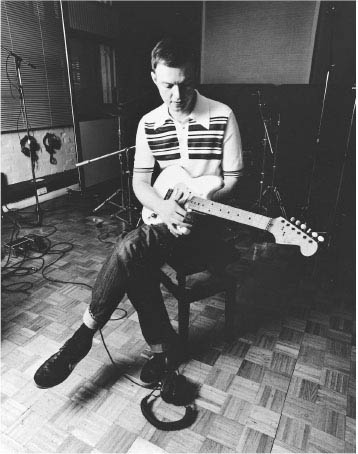

The second great event was Edwyn’s first tentative return to his studio. This had not been possible until he could climb stairs, as the studio is a level above ground, above what would once have been the stables for the fire station’s horses, and are now garages and lock-ups. My mother confided in me that during the hospital days it occurred to her that the logistics of simply getting through the door of the studio were immense. Could it be done? Yes, it could and here we were, tackling it. The steps up to the first level are a little tricky, being of cast iron construction, a type of fire escape, really, with gaps between, which were somewhat disconcerting for Edwyn. We had several capable fellows in attendance however. I can see Pav now, confidently placing Edwyn’s foot in a firm and safe spot on each tread, as he climbed the stairs, surrounded by bodies happy to cushion the blow should he wobble. Which of course he didn’t.

His entrance to the studio was somewhat muted. This is a complex and confusing world of which he was once lord. More than anywhere in the world, this was his home, an environment packed with detail that demanded encyclopaedic knowledge from anyone who would master it. Edwyn no longer possessed that knowledge. As he wandered around, looking at things, touching things, Seb pointed bits out, reminding him of when he acquired this, what he used to say about that, their favoured methods of using the lovely vintage microphones, little anecdotes from their recording past. But it became evident that we were in information-overload territory. You can’t have everything, all at once. I picked up from Edwyn a feeling of recognition and love of his studio, but also a patient acceptance that there was a great deal more work to be done before he would be ready to return.

Seb and Edwyn would make an attempt at working on the mixes of the album which had been recorded the previous year, but Edwyn was not able to contribute much and decided to shelve it for a while. Seb did rough mixes of the whole thing for Edwyn to listen to, to mull over. He even suggested that he could try and finish the thing on his own, without Edwyn. It absolutely cracked Seb up when he got a response in the negative: ‘That would be an … aberration!’

I had not heard these tracks yet. Edwyn and Seb seemed to have magicked this record out of nowhere. I had been in my office during the days of its recording, but largely stayed out of the way. Most of the work had happened at night time. They were past masters at what they did and required no interference from me or Hazel, or the ‘office girls’, as Seb archly referred to us. He used to leave us notes on the desk from the night before: ‘Office girls, need ink for the printer.’

‘Office girls, so and so phoned, re such and such. Get back to him. Now please.’

‘Office girls, blah blah not happy about quote. THIS WILL NOT DO!’

Since Edwyn had fallen ill the funny studio rhythm the four of us had shared for years had fallen apart. While he was in hospital, I would have occasion to go up there, where for many months it was dormant, quiet as a tomb. I would wander around, seeing Edwyn in everything, all his glorious confusion. It would make me heartsick; I felt bereft, broken, and would scurry away, back to hospital, back to the urgency of here and now. For Seb it was a rotten time. The studio without Edwyn, with all the uncertainty of the future and all the echoes of the past. Very hard.

Edwyn may not have been ready to go the whole hog in the studio yet, but he could visit it. The place was alive again. Seb and Bernard Butler, another friend, musician and producer, were keeping the home fires burning. Edwyn’s studio had a reputation of its own and it has continued to grow even as the boss has been wending his winding path back to fitness. In fact, Duffy’s world storming debut album, Rockferry was largely recorded there, with Bernard producing and Seb engineering.

•

AS AUTUMN LENGTHENED and winter approached, we made the long journey three times a week to Wimbledon for physio. The intensity of these treks I can still conjure up. Hours and hours in the car. We passed the time in conversation. I would talk, gossip, rant and rave and, initially, Edwyn would mostly patiently listen. In the early days of hospital I was issued with some leaflets advising me on the best ways of communicating with a person with aphasia. Here is some of the generally held advice:

I agree with all of the above. I just wasn’t brilliant at sticking to it. In stark contrast to the guidelines:

So, as sound as the guidelines are, Edwyn had to tolerate my approach which, although I initially worried that if I couldn’t undergo some sort of personality transplant he was going to be hampered in his recovery, turned out to suit us. Trudi (and after her, Sally, Edwyn’s other speech therapist) would very kindly not castigate me for my shortcomings, and they saw plenty evidence of them. Before long Edwyn would resort to ejecting me from his speech and language sessions as soon as he realised I was entering the prattle zone.

•

WE USED TO try all sorts of exercises in the car. I had a little book written in the 60s by an amateur therapist called Valerie Eaton Griffith, called A Stroke in the Family. She had devised a series of exercises, written and spoken, which had helped the actress Patricia Neal, first wife of Roald Dahl, come back from a near fatal haemorrhage which had left her severely aphasic. I adapted some of these for our purposes. For instance, I would ask Edwyn to list me six David Bowie albums. By October/November he would do well on this kind of question, which he would have found much harder in earlier months. Or synonyms and antonyms (harder). One thing that worked very well was when I began a sentence and left Edwyn to finish it, often with hysterical results. So I would say, for instance: ‘Whilst crossing Wandsworth Bridge the other day I couldn’t help noticing that …(Edwyn) … life is strange and beautiful!’ The answers were always mad, random and gleeful.

We did a lot of reading practice as we went along. Edwyn was a compulsive reader of street furniture, advertising, van logos. As he attempted to read every sign we passed it made me realise how little conscious attention I pay to the ridiculous amount of signage our city is crowded with. There is one that says ‘Controlled Zone’. They are everywhere.

•

EDWYN’S TECHNIQUES FOR speech recovery and reading recovery were necessarily repetitive and could come across to the unwary as dotty behaviour. I knew better, even from the start. It had to be done as his own form of brain training and he had no interest in the impression he gave others. His natural ego has been his saviour in this regard. Sometimes he and I are given a nice pat on the back for helping to ‘raise awareness’. In truth, Edwyn is detached from thoughts of how much or how little the world at large understands his experience. It never crosses his mind. He is entirely absorbed by his own life, his own fight. The impression formed by others is simply none of his affair. I take great delight in my role as onlooker as Edwyn engages with society at large in his own unique style. Mostly people are great, especially as Edwyn confronts the issue head on, announcing to taxi drivers, waiters, all strangers who register on his radar: ‘I had a stroke, you see. Six months in hospital. Not good, but I’m doing well at the moment. I’m getting there. I’m enjoying life.’

At this, most people open up, discuss someone they know who had a stroke, compliment him on his tenacity.

Occasionally, there is an awkward moment. Arriving in Glasgow recently, the plane touched down and the usual flurry to get off ensued. I was helping Edwyn on with his coat when an impatient guy behind shoved into him.

‘Excuse me,’ said Edwyn.

‘No, you can excuse me! I was here first!’ retorts Mr Impatient.

I explained that Edwyn had had a stroke and needed a bit of help, hence my squeezing in.

‘Well, that’s just brilliant …’

Eh? I’m sure it was awkwardness that made him say it.

Edwyn turned to him, wagged his finger and declaimed in a loud voice: ‘Just you behave!’

The poor guy couldn’t wait to get off. I was, of course, doubled up.

•

EDWYN APPEARED TO have developed a mellow, tolerant side since his stroke, much to my disgust. On our trips to Wimbledon, as well as badger Edwyn to get into whatever the hot topic du jour happened to be on talk radio – weighty or flighty – we listened to music too. Radio 2 was often on. We got into frequent disputes about the quality of the music. I found it mostly unbearable. He was much more complimentary.

‘Edwyn Collins, a nice guy? I’m not having it.’

‘Yes, I’m sweet and lovely now.’

Back in the day, he was known for his vitriol, sideswiping his contemporaries, playing with journalists, alienating all and sundry in interviews, a real smart mouth. I used to despair of him and celebrate him in equal measure.

Foreign journalists were a particular target, especially European ones who specialised in the banal.

Asked for the umpteenth time why he had called his band Orange Juice, he would say: ‘Because there was already a group from Scotland called Middle of the Road.’

Puzzled silence.

Or, to a Dutch journalist: ‘Because, in my country, Scotland, we have a drink called orange juice.’

‘We have that drink in Holland too.’

‘Do you?’

See what I mean?

Now he was pleasantly indulging all sorts of nonsense. I decided he was doing it to annoy me. There was a particular song on the radio that winter, ‘Nine Million Bicycles in Beijing’, which Edwyn claimed to love. It made me scream. An old music business lag called Mike Batt co-wrote and produced it.

‘Here we are at Wimbledon Common, Edwyn. If you can correctly identify the connection between this record and Wimbledon Common, you win a big frothy Starbucks.’

‘The Wombles!’

‘Correct’ (Mike Batt had his first hits as a singer/songwriter with ‘The Wombles’ in the 70s).

We listened often to Seb’s rough mixes of the album. I will always associate this record with those car journeys. I watched Edwyn deep in contemplation, as if he was trying to introduce himself to his former being, the man who had conjured up this layered world of ideas, words and instruments. Was that really me? was written all over his face.

‘I used to be an intellectual.’

‘I’m daft now.’

‘I need to get better. I must get better. I will get better.’

•

Revolution on the south bank

I poured poison in the think tank

Got out before the big crash

I caught the tail end of the whiplash

Staying out of the spotlight

Don’t get blinded by the limelight

I’m going back to the backroom

I’m operating in a vacuum

~ Back to the Back Room, 2002

THE OTHER MAIN thrust of recovery rested, of course, with Trudi. Her thrice-weekly sessions with Edwyn took place in the comfort of our living room, at the dining room table, which was soon groaning under the weight of books, notebooks, sheaves of speech-therapy materials, Scrabble tiles (used to help him reconstruct words from their component letters) and pencils. Trudi’s strategy covered so many angles, was so varied, so fascinating. Understanding the true nature of Edwyn’s language loss and the multifarious means of encouraging its retrieval took a long time for me to wrap my brain around, never mind Edwyn.

When I quote Edwyn in this book, I’m showing him off at his finest. Particularly in the first year following his homecoming, speaking was a task involving enormous effort and concentration. Trudi worked on his word production, his sentence construction, his cognitive understanding of linguistics and his reading and writing. Writing techniques were much more difficult to produce than reading, which Edwyn and I could beaver away on at our leisure, having been furnished with the correct strategies by Trudi.

Edwyn was tested on nouns and verbs, repeating the tests with a gap of a few months in between. The tests were done by video. A set of objects was shown, about seventy, and then footage of people or things involved in actions, or reactions. So, nouns and verbs. I was possibly cheating a little when we did it the first time, because I wanted to encourage him. I would pause the video to give him a little more time as the images passed by quite quickly. His score on naming the nouns, about thirty-odd out of seventy, was much better than the verbs, about fifteen. Edwyn likes to be able to quantify his improvement wherever possible, likes to compare where he is now to where he was then, so tests like this are great, because each time we repeated them the score would have increased as well as the speed with which he was able to complete the test. It also underlined what we already knew, that work on verbs was an area to concentrate on, to make speech more fluid, more understandable than trying to deliver his point as a list of nouns, his favoured method. For instance, he would say:

‘The man? Oh, sixties man. Hmm. Dundee, yes? New York. Oh, the guitar. The man. No, help me.’

He might be talking about Lou Reed; he might be talking about anybody. The Dundee reference might be when he remembers first seeing him. He needed an immense amount of support to convey his meaning. But fortunately Trudi had seemingly limitless ideas in her armoury and slowly, he advanced.

•

ON THE WRITING front, Edwyn’s problems were deep and complicated. I worried that he would never again be able to generate independent writing, the difficulties were so extreme. When we write as literate adults we employ a number of complex skills. In Edwyn these had been obliterated. We begin with the letter and the sound it makes. He couldn’t picture the letter A if you said it to him. To give an idea of the magnitude of the task:

The letter A. What does that look like?

No idea.

If you asked him to write a simple word like cat: C-A-T.

Nothing.

Breaking it down to its component sounds. Cuh, ahh, tuh.

Still nothing.

Asked to separate out the first sound of that word from the others, once again a blank was drawn.

Writing about it now, I am amazed to remember Edwyn’s commitment, his acceptance, his patience, his will to work, and above all, his courage. We assembled a list of key words for each letter of the alphabet, chosen by Edwyn. I seem to recall putting a lot of it together on one of our car journeys. He uses this keyword system still to help him visualise letters. It is easier to do this in the context of a real word. A is apple, F is fish, H is hotel, U is utopia. He uses lots of familiar names in the list: David, Myra, Grace, Nan, Petra, Edwyn, William, Robert. For a long time this work was more or less agonising, with tangible results coming so slowly. If a short sentence took you twenty minutes, with help, you could be forgiven for thinking that useful, independent writing was beyond your grasp, and therefore, lead you to question the point in the gigantic and exhausting effort to achieve such little reward. But Edwyn ploughed on.

•

EDWYN HAD BEEN working hard to find his way around a computer again. In order to achieve this he would have to re-acquire some tricky moves, things that we take for granted. Principally among them:

Sequencing: Making each move in the right order. From opening the lid of the laptop, switching on, choosing which application to open and so forth. Initially he needed to be cued up for every move.

Scanning: Casting his eyes around every area of the screen to find the area he should move the cursor to next. It was very easy to miss things. He had blind spots.

Selection: Sifting through the options presented on the screen and making a choice. Which requires self-confidence.

Typing: Edwyn had to familiarise himself with the keyboard lay-out as if he had never seen one before. He also had to train his left hand to type and navigate the mouse pad. Taking his ongoing battle with dypraxia into account, this was no mean feat.

In fact Edwyn was making terrific progress, perhaps because we could lead him to sites that really interested him. He had been an avid eBay buyer, one of the first in this country to cotton on to it, and was quickly able to recall his user-name and password. An automatic function, often repeated, which returned with ease. Amazing. I was also fascinated to see that his understanding of numbers had not deserted him. He was not so hot at verbalising numbers, but when he saw the prices that vintage guitars and microphones were going at, for instance, he was fully cognisant of what he was looking at. He would shake his head and say sadly, ‘All my bargains have gone away.’

I tried him on sums, too. To my astonishment, although oral calculation was unsuccessful, written work was pretty hot. I made them harder, with old-fashioned multiplication sums and long division. Still very good. Not always perfect, but pretty impressive.

•

BACK ON THE eBay trail, I asked him, ‘Do you want to bid, Edwyn?’

‘These prices? Pfff …’ His sharp eye for the going rate was working perfectly.

Eventually, he did have a go. And, with him making the decisions on how to pitch for it, he won a very peculiar-looking old guitar from the 1920s which, he explained to me, would have been a real cheapo back then. It has a strange chequered print on it and is just exactly the type of oddity that would have caught his eye in the old days. A few months later I opened my email to find that he’d pressed ahead with a bid on an amp, all on his own, no help. Another milestone had been reached.

‘Crazy, I suppose. I can’t play.’

•

To anyone who’s followed me

I offer my apology

I’m splitting up

I can’t afford to compromise

With someone I don’t recognise

I’m splitting up

The idea first occurred to me

While shaving rather cautiously

Because I bleed easily

My head is separating from my heart

I’m splitting up

~ I’m Splitting Up, 2002

FOR MOST OF his first year out of hospital, Edwyn, on pondering his career in the light of all that had happened, would say: ‘Retired, I think. A good innings. How many albums? It’s a lot, I suppose.’

He would deliver this assessment a little wistfully, a bit sadly, but with a sort of resignation.

Andy, Seb and I would always respond the same way. Let’s just wait a while and we’ll see.

At that time, Edwyn couldn’t see a way back to song writing, not least because he could no longer play the guitar. Edwyn’s right hand and arm have continued to be most stubbornly unreceptive to therapy. We keep them both in good order, with not too much tightness, but useful function seemed a big ask. Prior to his illness, I would have assumed that the loss of his ability to play the guitar, something Edwyn has done every day since he first picked one up, would have been too crushing a blow, really unbearable. And yet, he lives with it. It makes him sad, it makes us all sad, but it has to be accepted. And, with resourcefulness, worked around.

‘You are and will always be a guitar player, Edwyn. Nothing can remove that from you. And a collector. Carry on.’

In fact, Edwyn and I had been playing the guitar together, after a fashion (I’d had to take a crash course, never having played before), for a few months. In Northwick Park, Edwyn had several sessions with a guy called Matthew who worked for Nordoff-Robbins Music Therapy. This organisation is the music business’ favourite charity, with an annual awards ceremony as its major fundraiser. Edwyn had been involved with the Scottish wing since its inception. We couldn’t have imagined that he would end up as a recipient. I only saw him with Matthew twice. The first time I walked in on the end of one their sessions I was confronted with the astonishing sight of Edwyn playing the guitar and singing. Well, both of them doing it together. Edwyn’s left hand making the chord shapes, as it always does in a right hander, and Matthew strumming. The left-hand bit is obviously the more complicated thing. And singing together, a Beatles song, Edwyn lagging a little behind, the words suddenly unfamiliar. But what a thing to behold. Obviously, I would have to learn to strum: Edwyn knows dozens of guitar players but none of them are on tap, as I was. Strumming isn’t as easy as it looks, if you’re a woman in her late forties who has, until this moment, never shown any hint of ability or inclination to play. The instructions would be rapped out: ‘Slow down!’ or ‘Speed up!’, but with a little practice, I was soon strumming upwards as well as downwards. I quite fancied myself. And with Edwyn doing the clever stuff, I could almost convince myself I was playing the guitar.

Sadly, I haven’t progressed very much. It’s a pretty basic approach. But this seems to suit Edwyn. One of the first things he did was to work out chords for his hospital epic, ‘Searching For the Truth’. And then he came up with a nifty little middle eight (for those that don’t know a middle eight is the bit of a song, usually in the middle, that introduces a bit of added interest by breaking up or moving away from the simple structure. It tends to be eight bars in length, hence the name). All with me strumming along good style.

Will picked up a guitar for the very first time, just shy of his seventeenth birthday, and hasn’t put it down since. Carwyn Ellis, our friend and Edwyn’s band mate, who can play literally anything brilliantly, took him under his wing and showed him his first chords when Will started to show an interest. Until then, we were not sure he would go this route. He used to look at us when he was younger and say: ‘Don’t expect me to go into the family business.’

We never did, and Edwyn was very adamant about not pushing him. He has a clear belief that if you are going to be a musician, you will be. I’m not sure this applies in the classical field, where teaching and discipline are so important, but certainly in the confines of rock and roll, I agree. Edwyn is self-taught and so is his son. Edwyn came to it at a similar age and was similarly obsessive. I’m sure Will would have started playing music regardless of his dad’s illness, but there is a special joy in watching him play, now that Edwyn can’t. His father offers advice and corrections, which they sometimes argue about, as I look on with a beatific, motherly expression. Although I am slightly putout about my role as chief strummer being usurped.

•

WILL WAS ALSO fantastic in helping in his dad’s recovery in another way. He introduced Edwyn to something that would prove to be the most valuable weapon in our armoury as we fought on with the battle to recover writing. MySpace. To the uninitiated, it’s one of those dreaded social networking websites. But to Edwyn, it was to be the key that unlocked his creative writing abilities and helped him tentatively back to the domain of the written word. This site works particularly well for bands and musicians as you are able to use it as a shop window for your music, old and new. You can also keep those who are interested abreast of your activities and receive feedback from your ‘friends’. Being a bit backward and out of touch, we had never heard of it when Will introduced us to the idea. Within minutes of creating his profile, however, Edwyn was receiving online correspondence. This really excited him: instant feedback from the outside world, a world he had felt so cut off from since his illness. I had shown him the huge quantity of messages he received while in hospital and explained how they had helped sustain me. He had really appreciated them, but MySpace feedback was current, about where he was now. It also had things he could count. Post-stroke, Edwyn likes counting, a lot, as I mentioned. He still appreciates quantifiable things and MySpace gave him plenty of measurable data.

I also introduced him to the world of blogging. In my own world, I’m not keen on all this self-absorption stuff, but I could certainly see its potential for Edwyn. We began working on his mail, postings and blogs together, every day. Edwyn would mostly dictate, but would also try a few painstaking words on the keyboard himself. I would add a little dash of artistic licence, to tidy things up, and all in all it worked rather well. As we went along, he gradually tried more and more words. We assembled a book of his most frequently used words, favourite catchphrases, odds and ends, which we still add to today. It took more than a year of undiluted MySpace addiction but, two and a half years after his stroke, he was answering his own mail, unaided. His letters are short and sweet, but the progression continues at a steady pace. This is a mind-boggling miracle to me as I was deep inside Edwyn’s aphasia for a long time. I knew what the intricacies of it were, so to see him with this degree of independent ability restored to him was breathtaking. And wonderful. But I don’t underestimate the achievement. Nothing walks to him. He fights tooth and claw for each victory. Press on, Edwyn.

•

YOU WILL REMEMBER Edwyn’s instruction to me as we left hospital for good to get going on reading again? We were slogging away at that, too.

Our niece, Sarah, was five. Hazel, her mum, still had some Ladybird Key Word scheme books that she had started Sarah on. Hesitantly, she suggested them to me, not sure how this would go down.

Perfect.

Edwyn couldn’t have cared less about the simplicity. The task had begun and that was all that mattered.

I bought all the other books in the Ladybird set, which divides learning into twelve stages, three books in each. They have become unfashionable as a tool for early learners in schools, which amazes me, because they work. The idea is simplicity itself. Most of us will remember them as the ‘Peter and Jane’ books. The books were launched in the 60s and were written by an educationalist called William Murray. He used to work as an adviser to a borstal and went on to be the head of a school for what was then called the ‘educationally subnormal’ (ah, those halcyon pre-PC days!). When I tell Edwyn this he pipes up,

‘That’s me!’

Murray’s research, together with an educational psychologist called McNally, found that 100 words make up half of everything we read, speak and write, and a further 300 words account for three-quarters of our verbal input and output, and thus they devised the reading scheme. The beauty of this system for Edwyn, once again, was that progress was clearly demonstrable as you move up the levels of difficulty. We could look at where we were and place it in the context of where we had been last week, last month and, eventually, last year. Edwyn would never be quite sure he was getting better at anything unless you could show him concrete proof.

Although the Ladybird scheme was designed for children in the first stages of reading, Edwyn was learning to read again in quite a different way to a child. As time went on, it was clear that he retained a memory of what it meant to be a reader and of the content and meaning of many of the books he had read in his life.

I recall during a session with Trudi he had dug out some of his favourite books and she was using them as the basis for a discussion. Trudi’s skill was such that Edwyn would become immersed in thought and unexpectedly produce a full sentence, heavy with relevance and lyricism. One book, Oblomov, by a Russian called Goncharov, almost defies description its themes are so abstract. But Edwyn found his way to the core of the thing:

‘A man brought to the brink of disaster by his man-servant.’

And Trudi helped him write it down. Can you imagine the pure elation I felt as I saw this indication of potential revealed?

Often, but not always, he could recognise complex words immediately, on the front page of a newspaper, for example. Words like ‘policy’ or ‘referendum’ could suddenly jump out at him. Words which were descriptive, or loaded with meaning, like ‘angry’ or ‘turquoise’ also seemed quite recognisable. But the most-used words – like this, them, those, there, then, where, when, were, was, with, up, on, of, in, if, is, as, at, are – all of these were pure Greek. The most stubborn of all were, incredibly, a and the. He would stare and stare at these two. There is so little to them, that they would give him no clue as to their identity. Thousands of times I would have to step in and say them, before they started to stick. He also needed very large print to work with. Hence he could cope with headlines in newspapers, with help, but not smaller text. The effort required to restore a reasonable degree of familiarity with the little words, the ‘abstract’ words with little integral meaning, was immense. Every day, building it up, grinding it out. It could be deeply frustrating and tediously dull. It could also be wonderful, satisfying, pleasurable. You never really knew how it would go from session to session. We both had to dig deep to keep going with it some days. And in the context of all the other therapeutic activity going on, the temptation to skip a day was great. But we almost never did.

I can’t quite remember how long it took us to get to the end of the scheme. Several months, anyway. We moved on to proper books with stories for kids. And within much less than a year, to a series of books I found to be really brilliant. An Edinburgh publisher called Barrington Stoke produces books that have been specifically adapted for young people, including teenagers, with reading difficulties like dyslexia. Books with older themes but printed on a cream-tinted paper which has been proven to be easier to read from. Also the typeface has been researched; the spacing, the font size. These proved to be an enormous boon. I was introduced to them by an independent bookseller in Wimbledon, after I had described our predicament. As Edwyn slowly progressed through the months, again I could select from an ascending level of difficulty, to keep nudging him forward. No sooner would he have mastered a stage than I would annoyingly be shoving him on to the next. Infuriating for him, as he often would have preferred to luxuriate at a nice comfortable level for longer. Lots of deep sighing and tutting would accompany each new beginning.

I’m not a natural teacher. My patience, not my strongest suit, would soon be exhausted if Edwyn proved the least bit resistant. Whilst we made great progress and most sessions were quiet and satisfying, reading together was not always a peaceful activity. We could get on each other’s nerves and, unforgivably on my part, would from time to time get into a fight. Edwyn would get fed up with the effort and clam up and I would start lecturing and hectoring. Then I would hear myself, stop dead in my tracks, overcome with guilt, beg his forgiveness and promise never to get like that again. Until the next time …

•

WE LIVED OUT the last months of 2005 in a kind of a dream. Life was so busy, lots of appointments, tons of therapy, but there was soon a pleasant rhythm established and the novelty of simply being home from hospital had certainly not worn off. We were a little blissed out. Among all the hard work there seemed to be plenty of time for just enjoying life; a heightened appreciation of the pleasures of spending time with each other and Will, with family and friends. Edwyn had lots of visitors, everyone joining in a reserved celebration of his homecoming and returning strength. Every day we would go walking, the quiet winter months being the best time in London’s parks and heaths. It felt like we had them to ourselves. Gradually increasing our distances, at first Edwyn walked with his stick in his left hand, me uncurling his right hand and supporting him on his weak side. Then he no longer needed me as a prop and he could go further without needing a rest. To walk a circuit of Queen’s Park without stopping was a goal we aimed for. By mid November he achieved it.

•

IN PHYSIO, ELLEN had prompted Edwyn to try walking without his stick at all and had been impressed by his bravery at trying this. She explained how scary it is when you have such limited sensation on one side of the body. Like stepping off a cliff. Edwyn trusted Ellen implicitly and would try anything if she said he should. So we then would try a few steps without the stick during our walks. Although effortful, he soon increased his range. By springtime we had increased the circuit to take in the top half of the park, more hilly terrain and he would do a goodly part of it with no stick. I walked along slowly beside him often feeling the cold, whilst Edwyn would be boiling hot with the aerobic effort.

We had many crisp, winter walks on Saturday afternoons in beautiful Regents Park, bundled up in duffel coat, hats, gloves and scarves, usually followed by an early dinner at one of our favourite spots in Marylebone High Street.

Edwyn had forgotten London, his home town for over twenty years. He didn’t recognise Kilburn, or Queen’s Park, or any routes as we criss-crossed the city on our way to appointments. I kept up a running commentary, pointing out landmarks, recalling stories and incidents from down the years to give him some context with which to jog his memory. Over time this bore fruit and as we walked the streets and parks, the clouds would sometimes suddenly part and Edwyn would exclaim, ‘Oh, oh, I remember! It’s back!’ How exciting for him. How incredible these moments of illumination must have been.

•

IN OCTOBER, WE were having Sunday lunch at home with Susan and Andy, who, once again, had cooked, when Edwyn froze in pain at the table. I was terribly alarmed. The pain was in his leg, something new. After about a minute of squawking, the pain was gone as quickly as it had come. Edwyn started moving his leg around in wonderment. He had instantly acquired a few degrees more feeling. Moreover, the low level pins and needles that he claimed to have had constantly for months had completely gone, never to return. We looked on speechless as he stomped up and down shaking his head in disbelief. Ellen had no explanation for it. It’s the mysterious thing that is brain recovery. It will sometimes defy explanation.

•

‘REAL’ LIFE, OF course, would still intrude on the routine, from time to time. We were at the hospital one morning for another nine o’clock Botox appointment when the house had an attempted break-in. This was actually the second time in a year. We were burgled while Edwyn was in Northwick Park. I came home from hospital one night, around ten, walked in to my living room and took in the broken glass, half brick on the floor, missing laptop, iPod and camera. A narrow side window had been smashed, so the culprit must have been very slight, most likely a youngster. My alarm had been on the blink and, of course, I hadn’t got around to dealing with it. I sat on the floor, looked around and decided I couldn’t care less. Compared to what we’d been through and were still in the middle of, it seemed like so much nothingness to me. Will was at Hazel’s that night and came back over with her; sister to the rescue as usual. Hazel fumed as the police didn’t bother to show up until the next day, when they got a piece of her mind. They sent round a right pair of thickos.

Cop: ‘Where did they come in then?’

Hazel: ‘The broken window? Obviously it’s a kid, the size of the opening.’ (It’s about six inches wide.)

Cop: ‘You’d be surprised. I could probably get through there.’ (He’s a big fat guy.)

Hazel (note of derision): ‘Go on then.’

I got the window fixed, put some bars up, got the alarm sorted – with a police monitor on it this time – and went about my business, putting the whole thing out of my head with ease.

Our prolonged absences from home had clearly not gone without being noted by the toerag element in our neighbourhood, though. As we returned from our Botox appointment I saw Amete and a police car at the house and our front door completely splintered. A passer-by had seen two young men kicking the door down; no mean feat as it was double locked. The person had witnessed one of them brace himself on Edwyn’s handrails so he could kick it really hard from behind. By the time they had bashed through it, the alarm was activated, the passer-by had called the police and there was no time left to get anything, so the front door damage was all that was achieved. In the year that followed we were to have two further attempts, both fruitless. I can’t say that it didn’t bother me at all, the inconvenience of the damage, but I had a different perspective on minor domestic incidents of this nature. Water off a duck’s back. I beefed up the security a little more each time as were obviously being targeted and forgot all about it. Touch wood, the last few years have been trouble free.

•

AT THE END of November 2005, Edwyn got the word that his titanium plate was ready and he went back to the Royal Free for his last operation. It was good news. The last bit would be done and dusted in time for Christmas. The vulnerable concave hole in the side of his temple, which we had become strangely accustomed to but which did look rather peculiar, would finally be covered. But, returning to the scene of my nightmares was unexpectedly hard.

In and around that building, I couldn’t walk anywhere without flashbacks. Edwyn was relatively unperturbed about facing up to an operation, something which a year ago would have had him horrified. He had been through so much, he was inured to normal fears associated with surgery. We arrived on Thursday night, met the consultant who reassured us that they intended to give Edwyn a big dose of anti-MRSA drugs during the op, just in case, and that he wouldn’t be in for any length of time. He met a few of his old nurses, including Jo, who had seen him through the darkest days. The unpleasantness of being in hospital again was offset a little by the pleasure of showing him off. I had to leave him alone in hospital overnight, but this time he was stronger, more able, and the comparison with the man who had been here earlier in the year was stark.

I was back at the crack of sparrows and Edwyn was whisked away. The operation was quite lengthy and I was allowed to sit with him in the recovery ward, something that had never happened before. By evening he was settled peacefully but woozily and I wended my way homeward, experienced enough to know that by the next day he would seem so much better. A quiet Saturday, with a visit from Andy with his trusty food parcel, and we were told that after a doctor’s visit on Sunday, I could take Edwyn home.

We were back home by Sunday lunchtime. A couple of hours later, Edwyn shot a temperature, and butterflies took flight in my tummy. But the hospital reassured me that it was normal post-op behaviour. We held fast and soon all was well. For ten days Edwyn sported a long arc of steel staples on his shaved head, but this time the wound healed, no infection took hold. We were in the safety of our own home, far away from the bugs that stalk hospitals.