I’ll take a train

I’ll take a plane

Away up north where they know my name

But they don’t bug me

The way that some folks do

I’ll take this guitar

I’ll maybe start anew

Because otherwise I’ll stay down here and stew

Upon a Hill of Many Stanes

Five miles south of the Great Grey Cairns

I felt the full force

Of five thousand years

And I felt the sting of time’s eternal tears

~ Liberteenage Rag, 2004

WHEN EDWYN HAD first recovered consciousness way back on intensive care in March, I had begun whispering to him about getting him better and about where we would go. To Helmsdale. I wanted to give him something to fix on, to aim for, and there was nothing that would have more meaning for him than this place.

Helmsdale is a small fishing village on the far northeast coast of Sutherland, which, along with Caithness, is the most northerly county on the Scottish mainland. Edwyn’s mother’s family go back generations in the village. It grew up in the early part of the nineteenth century when the inhabitants of the nearby strath (a wide river valley) of Kildonan were forcibly removed from their smallholdings by their landlord, the Duke of Sutherland, and either emigrated to the New World in vast numbers along with other evictees from various parts of the north of Scotland, or formed new fishing communities along the coast. This period is infamous in Scottish history, known as the Highland Clearances. Edwyn and William’s ancestors became stonemasons and builders of some renown, rather than fishermen, and many of the buildings in the local area were constructed by them.

When we were first together Edwyn told me many stories of this magical place where he had spent every summer holiday of his childhood since he was seven, in the company of his grandparents. His grandfather, Dr Hugh Stewart Mackintosh, was born in the house in 1903, the middle child of a family of seven. A very clever and able boy, he went to the University of Glasgow at the age of sixteen to study mathematics. The education he received in the village school was first-rate. Some of his and his sister’s text books on English literature and philosophy are still in the house, with handwritten notes in the margins, and attest to the high standard of scholarship it was possible to achieve in a small Highland school in the early part of the last century. Way beyond anything our children learn today. Eventually he became the Director of Education for Glasgow, a famous educationalist with an international reputation. And he was capped many times for Scotland as a rugby player in the 20s and 30s. Something of an over-achiever!

When I met him in his early eighties, he was still an impressive and slightly intimidating figure. He divided his time in his retirement between his home in Glasgow with Edwyn’s grandmother and the home of his boyhood, now under his custodianship.

•

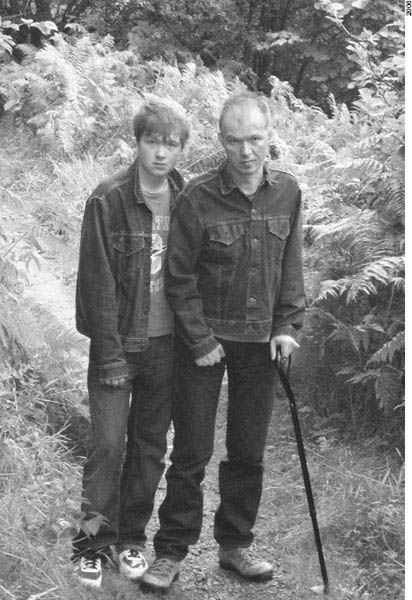

IN 1985, I visited Helmsdale for the first time with Edwyn. We spent two weeks in September with his grandfather at Bay View, the family home. As we drove north, Edwyn recalled the thrill of driving to Sutherland with his Grannie (just as in our family, she was the driver: Edwyn’s grandfather drove very little), as she marked off the rivers they crossed with an old song: ‘The Dee, the Don, the Deveron…’

I don’t know what I was expecting but after a few days marching the hills and the rugged coastline, for anything up to twelve miles a day, I started to think I was on a Duke of Edinburgh Award scheme rather than a holiday. I’m from the industrial central belt, and at twenty-seven had barely been exposed to proper outdoors conditions. As I looked up and ahead at the eighty-two-year-old man scaling a cliff or the steep face of a burn he would turn around and call to me, ‘Are you all right there, lass?’

I decided to ignore the townie inadequate I was and press on, trying to keep up with Dr Mackintosh, forged in steel, and Edwyn, natural mountain goat. The glorious surroundings, breathtaking, endless, empty except for the wildlife, distracted me from my screaming muscles.

‘You’re doing well, lass, you’re not a moaner.’

‘I’m doing quite a lot of inner-moaning, believe me!’

After two weeks, I was broken in, no longer felt the pain, transformed by the place. Coming back to the old house, cooking dinner and sitting by the fire listening to Edwyn and his grandfather re-shaping their relationship with one another as adults, I fell in love with every aspect of life in Helmsdale…

Edwyn had been so close to his grandparents growing up, but as he chose his unusual career path, I think his grandpa found the life he was pursuing and the music he made quite unfathomable. A man with a tremendous work ethic, (‘Work, work, work, we must work, boy …’) the life of a pop star was entirely baffling. Walking along one of the many beautiful beaches with him one day, watching Edwyn in the distance exploring rock pools just as he had always done as a wee lad, Dr Mackintosh had a go at reaching for Edwyn’s world.

‘I’ve been looking into this pop music. Now, would I be correct in thinking that the gist of the thing is, one takes a refrain and repeats ad nauseam?’

‘That more or less sums it up…’ I nodded in laughing agreement.

His Grannie, Mary Wilson Mackintosh, on the other hand, was fully accepting of Edwyn’s artistic bent. As his number-one fan, she had his vinyl albums displayed around the house. The staff in her favourite Glasgow record shop would greet her: ‘Here comes Edwyn’s Grannie!’

When Petra and Myra put the memory book together for Edwyn back in hospital, there were many letters in it that revealed so much of the wonderful affection he was held in by his grandparents, for whom he was the first grandchild. As Edwyn grew up they exerted a powerful influence on him. When Edwyn was approaching his second birthday, his mother had an illness that confined her to hospital in Edinburgh and he went to stay with his grandparents in Glasgow. Understanding the pain of separation, Dr Mackintosh wrote often to his daughter and she has the letters to this day. They were reproduced in big print for Edwyn in the memory book. A few excerpts serve to give an idea of this fascinating couple and their relationship with their grandson:

15 May 1961

Of course, we are all longing to have him – the trouble is going to be to keep him from being thoroughly spoiled. He is such a fine wee chap. I’ll get him into gardening with me. There are plenty of tools to satisfy his every wish, and ground and grass to scamper about on. At the weekends I’ll take him personally in hand and introduce him to the things that mean so much to me.

28 May 1961

I’ve just come from a ‘walkie’ with Edwyn in Newlands Park. We always have great fun together on these expeditions … and his tongue is never idle. … Before tea we had a game of football on the grass in front of the house – you could hear him laughing and spluttering houses away. And then in to tea. His appetite is good but his tastes are erratic. The banana was discarded halfway through and then he was on to pancakes and butter and jam. When he has had enough he says a decisive ‘Feenish!’ and slides off the chair.

15 June 1961

Edwyn was in glorious form – I don’t think I ever saw him in such a devastating mood … There was no stopping him and I can’t tell you when I enjoyed myself more. It was particularly refreshing after the kind of day I had at the official opening … it was good, especially good, to be with Edwyn, his eyes bright, his cheeks like apples and behaving like a variety star. We’ll have to watch that we don’t spoil him – and that’s not going to be easy, let me tell you.

Later, when the children holidayed at Helmsdale letters flew back and forth. Edwyn had a mania for wildlife and by the age of ten was an expert on British birds and all sorts of other flora and fauna, much to his grandfather’s pleasure.

5 May 1974

Dear Edwyn and Petra

Today is Sunday, a day of supposed rest here, so I’ve laid down my tools and wandered off along the shore to the Green Table, the Ord [beautiful local landmarks] and beyond. What a wonderful day it has been. The sun was shining, the sea, green, flecked with white, and the wind was coming in at the headlands, clean and salty and aseptic. The tide was far out so I crossed over the Green Table into the Baden, past the Pidgeon’s Cove and round Aulten-tuder burn into what we used to call the Breckan Face. Everywhere there were sea birds swooping over my head as they rose from their nests. I saw a few with 3 eggs, quite a few with 2, more with one – the rest – late developers perhaps – with none at all. Edwyn would have loved it – Petra too I’m sure. The cliff face was covered in celandine, sea pinks, blue-bells and hosts of yellow primroses. A wonderful display, and everything so clean and fresh. I felt the years lift off my shoulders and I followed the familiar routes of my boyhood days – and, wonderful to tell, managed them … I have yet to go to the Clett (Edwyn knows this favourite spot of mine) and there everything I saw can be seen in concentrated form. But I miss the guillemots and puffins that I used to see as a boy – perhaps the fulmars that I now see everywhere have pushed them out. But the razorbills are a delight, so immaculately dressed in their black and white and their stripes. Just like busy young advocates in Parliament House.

I have reproduced this letter in full because Dr Mackintosh describes so much more eloquently than I ever could the utter magic of an expedition day from Helmsdale and why Edwyn, and latterly I, are so devoted to the place. The route he describes is now familiar to me, but pretty hard work. I have never been to the Clett, a vertiginous cliff. Much too scary for me to try, but Edwyn has some hairy stories of his treks there. The birdlife on offer enticed him.

10 August 1975 (Dr Mackintosh to Myra)

On Friday we climbed over the Green Table into the Baden and, as the tide was well out, we managed to get round to the mouth of the Aulten-tuder burn and even further. I never went further as a boy than they [Edwyn and Petra] managed to do. And they did it cheerfully and in great excitement. They are great on these outings: they’ll climb anything and everything and quick to see and hear anything of interest. Very good companions – I could ask for none better. Plenty fooling too – the nonsense these two can keep up, mimicking some characters of their vivid imaginings in domestic scenes has to be heard to be believed. They carried on this dialogue all the way from far up Kilphedir burn till we reached Bay View. And they finished up fit and still full of cheer.

There are many more letters in the book, which gave me a glimpse of the intense happiness Edwyn felt when he was a child in Helmsdale. It was strange for Edwyn, aged forty-five and fighting his way back to health, to muse on the relationships of his young life. As he grew up into an awkward and headstrong teenager, who did fine but did not excel academically, relations were not always so easy in this tight-knit family, but affection and loyalty remained firm.

I love this next letter. When I read it to Edwyn in hospital, he was hugely amused and rather touched. The effort made to stretch across the generation gap is palpable.

14 September 1980 (Dr Mackintosh to Petra)

I think of you a lot, Edwyn also. I do hope that this sudden and most welcome publicity that he and ‘Orange Juice’ has got is not something that has happened more or less accidentally, and that it presages growing success and achievement. While I say that, it is comforting to know that he is doing something that he really enjoys, and even if his group were never to achieve major success, the fact that he is so compellingly involved in these interests of his is a guarantee that unemployment can never be the blight it is for so many young people. Good luck to the lad.

And the only letter surviving from Edwyn himself to his Grannie.

(Undated, some time in the early 80s.)

Dear Grannie

Sorry for being so negligent and Lazy with regards to your much appreciated letters. I hope you enjoyed us on T.V. I’m in the best of health, spirits, etc so don’t worry on that score. The group’s quite successful so that means a lot of arduous trips back and fourth [his spelling] to London. However, it sure beats ‘working.’ Ha ha. Love Edwyn. XX

Edwyn and his Grannie’s relationship was characterised by mutual mischief. She only died in 2007, at the tremendous age of ninety-seven. She was much affected by the news of his stroke: ‘But he’s so young.’ She would refer to him as ‘a darling boy’. Edwyn sang ‘Home Again’ for her at her funeral, which I’m sure she would have loved.

•

THE HOUSE ITSELF, Bay View, is part of the draw to Sutherland and Caithness. Built and extended by the various generations of the family, it is solid and cosy. In 1989, Dr Mackintosh died, a huge loss to his family. He was eighty-six, but because of the enormous physical and personal strength he exuded, it still felt as though he had died prematurely. The house passed to Edwyn’s uncle and, nine years later, in 1998, he decided to sell it. For us, the timing was good. We were flush with the success of ‘A Girl Like You’, and to our great excitement, the place that felt more like home to Edwyn than anywhere else, was set to become ours. With much less occupancy since Dr Mackintosh’s death, the house was in a rundown condition. It needed a lot of work. Edwyn doesn’t like change and was worried that it would lose the old feel. He even used to talk about particular smells he associated with the place and how could we preserve them? I didn’t really have an answer to that one. But all electrics, plumbing, roofing, walls, windows, floors, kitchen, bathroom decorating had to be tackled. The house had never had central heating. I thought that would be a good idea. Edwyn looked unsure; freezing at night was part of the Bay View experience. Thankfully, I won.

Two and a half years later (planning consents and Highland builders move very slowly … beautiful work, but slow. My brother David, an electrician and great all-rounder, had been a great help in the process) the house was finished and we spent our first summer there, getting it shipshape. It got the seal of approval from Edwyn. I hadn’t ruined it. Much of the old furniture remained, the same feeling, but with a few more modern comforts. Even the smells came back eventually, apparently. I’m still not quite sure what they are.

I sorted out all the construction stuff and Edwyn did the pretty, homemaking bits at the end. Our usual reversal of the traditional roles (Edwyn has always claimed I have enough testosterone for both of us).

Since then we spend as much time as work will allow in Helmsdale. For me, that is never enough, but I look forward to seeing my dotage out in this wonderful house, in this wonderful part of the world. We have many friends in the community who have welcomed me. Edwyn is considered one of their own.

•

OVER THE HOSPITAL months we talked about Helmsdale many times. It seemed like a far-off dream. The idea of getting back there; longed for but hard to imagine.

The last time we were there was just a few weeks before Edwyn fell ill. He had been asked to deliver the address to the haggis at the annual Burns Supper, celebrating the birthday of Scottish poet and hero, Robert Burns, in the nearby hamlet of Portgower. This was a real honour to be asked to do and we had a great night. The Fraser family – Elizabeth, Donny, Ann and Lucy – to whom Edwyn is related through his great grandfather, had made him a memory book of that night and of other places and things in Helmsdale.

In late January 2005, our friends in the village, Tommy and Sharon, were just about to move into our house for a period of some months while major works were taking place at their house. We’d suggested they come and take refuge in Bay View, which is where they were living when they heard the news of Edwyn’s collapse. They kept vigil there for us throughout those rotten months.

After Edwyn’s successful operation to insert the titanium plate, we decided to plan for Christmas in Helmsdale. In mid December we did the traditional huge load-up of the car. Will put the discs for the journey in the CD player, including his annual Christmas compilation; he makes a copy for all branches of the family, and it’s always a creative treat. Finally I piled Edwyn in the front and Will in the back (when he gets settled down for the drive in the back seat, with stuff piled around him, Christmas has officially started) and we set off.

We usually go north for Christmas; for many years we went to Glasgow and more recently sometimes to Helmsdale. For William, a Christmas spent in London isn’t really Christmas as he likes to be surrounded by family and chaos. This year though, we were having a quiet one in the calm of Bay View. First of all we would spend a few days in Glasgow to break Edwyn’s first really long journey and see the family on both sides. I didn’t know how he would handle such long periods in the car, but you never will know until you try, I reasoned. Edwyn sailed through the journey with no difficulty. All we had to do was stretch the legs a little more often than usual.

We had a happy reunion in Glasgow and then the lovely drive northward beckoned. After all the horror, it was the sweetest relief to pull up at the house, to be welcomed by our friends who had made dinner, had the fire roaring. Utterly spoilt and utterly happy. The sensation of falling asleep with my family safe around me, back in the bosom of the Scottish Highlands, Christmas coming, was gorgeous.

•

AFTER A STROKE, walking on any surface that is not even and solid can be a bit of a nightmare. Edwyn was nervous of grass, gravel, uneven pavements, slopes, kerbs, the lot. But with a little gentle cajoling, he tried everything. And, like the rest of us, he’s not keen on bad weather. We can do cold, sharp weather, but wind or rain are a pain. Especially together. Especially wind, which throws him off balance and makes him slightly panicky. He hates it.

Our biggest challenge to date was coming up. I was desperate to see him walk on a beach again. Under the old radiator in the kitchen his hiking boots had been standing guard, untouched, waiting for him to return. Sharon said she used to look at them first thing every morning while they were living at the house, a sort of talisman for her during the very scary days. They’re old boots that used to belong to Edwyn’s grandfather, inherited after his death. Later, she became so superstitious about them, nobody was allowed to touch them. She would clean around them. They had to stay exactly on the same spot. A couple of days after our arrival I called her to say sorry, the boots had been moved. I had got them on Edwyn’s feet and we had hit the beach. The boots, with their high sides, gave him great ankle support on the squashy sand. Sharon and Tommy were jubilant. The boot vigil was over, all was well.

•

WE ARE ABSOLUTELY spoiled for choice when it comes to beaches in the north east. Don’t tell anyone, but the weather is often beautiful and benign and we have a plethora of wide, white sand beaches that go on for miles. The access to some of our favourites near the house was tricky and strenuous, so for our first attempt we tried Dornoch. This is the county town of Sutherland, a handsome burgh, with its own small cathedral, an extremely famous golf course and a magnificent beach that is easy to get down to. On the soft sand, Edwyn found it more stabilising to lean on my arm on the left side, rather than his stick, so I could absorb his wobbles. This is a technique we use on difficult ground to this day, so I now have an over-developed, muscular right forearm. But a few steps on the sand later, Edwyn protesting loudly, me whooping with delight, Will trying to pretend he didn’t know us, and we had opened up another avenue to returning pleasures.

Nowadays Edwyn protests far less about a lengthy walk on the beach, except when I make him walk into the teeth of a winter gale. He’s learned to be very suspicious of the positive spin I put on the weather, the length of the walk, etc: ‘Just round that corner and we’re there. Nearly.’

‘Oh, look, there’s the sun trying to come out.’

‘How brilliant was that? Think how satisfied you’ll be we did that when we get back home. You were fantastic.’

‘Look at the roses in your cheeks!’

I’ve been warned off using ‘child’ psychology by him many times but I persevere. I use a variety of tactics. Bullying, wheedling, huffing, threatening, bribery, cheerleading. Sometimes all at the same time. As long as we get the right result, which is, Edwyn accedes to my demands. He wants to really. If he didn’t want to co-operate, no amount of trickery would persuade him.

•

WE HAD A perfect Christmas. Nan drove up from Glasgow on Christmas Eve. On Christmas morning everyone was a little spoiled. We had the most impressive Christmas tree, acquired by Sandy, our friend and Bay View’s head grounds-man and chief custodian when we’re absent, from what he calls his ‘private forest’. Between him and Tommy, nothing happens around the place but they know about it. In recent years there have been potential landslides, floods, boiler explosions and seized-up heating problems, all averted by the vigilance of our crack team. I cooked the dinner which, if I do say so myself, wasn’t half bad for me, and we were joined by Tommy and Sharon. Over the holidays we had the chance to catch up with all the friends in the village, who gave Edwyn a warm welcome back. We saw the New Year in with David and Ricky and settled down for a few days’ peace before heading south and back to the old therapy routine.

As well as our daily walks if the weather was being kind, Edwyn toiled an hour or so a day at the kitchen table on the holiday homework that Trudi had prepared for us. Another required element of his day was his drawing session. For this he needed no encouragement. He couldn’t wait for all else to be done with so he could get down to drawing.

•

THE SON OF parents who were both artists (who met at art school), whose father taught drawing and painting at art school in Dundee, Duncan of Jordanstone, (renowned for its association with many of Scotland’s most acknowleged painters of the twentieth century) for many years, and who grew up surrounded by painters who were friends of the family, it is perhaps no great surprise that Edwyn turned out from an early age to have a talent for drawing.

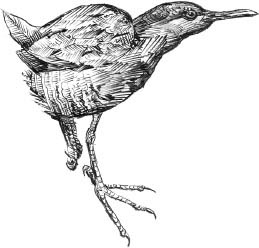

When he was nineteen and had dropped out of art college, he got a job, a real job, with a salary, for about a year, as an illustrator for Glasgow Parks Department. This job involved devising nature trails through areas of parkland, aimed mainly at schoolchildren, and then designing and illustrating the leaflets to guide them through, drawing the various flora and fauna they could expect to see along the way. Myra has preserved some examples of his work which have been reproduced in his scrapbook. They are meticulous, accomplished pieces of work. For a nature-loving draftsman this was the perfect job. Pretty jammy for a nineteen year old, too, I think. Sometimes he would guide parties of youngsters through one of the walks. These were often kids from the less salubrious bits of Glasgow. He tells how, on account of his unusual style, and his youth, the kids would shout at him, ‘Haw sir, are you a punk?’ (this is 1978/79). ‘Yes children,’ he would say, ‘I’m Nature Punk …’

The parks department ran something called ‘The Nature Trailer’ as an educational aid, which Edwyn would be called upon to man. It was an ordinary caravan fitted out with various natural history bits and piece; lots of stuffed things. Edwyn recalls the young female resident taxidermist working away doing revolting things to dead creatures in her corner of the office. In the office! She wasn’t too popular with other members of staff due to the smelliness of the job. Edwyn, of course, found it fascinating. One day the nature trailer was parked in a notorious bit of Glasgow called Bridgeton, where he came under siege as the caravan was stoned by the appreciative local youth.

When he gave up this, his only ever actual job, to throw all his energies into the band and the label, he continued to draw, contributing to the look and design of Postcard Records and producing his own artwork for record sleeves on many occasions down the years.

He used to talk of a fanciful project for his later years when being a pop musician would no longer be on the cards; he thought he would do a complete set of new illustrations of the birds of Great Britain. A big project, it would take years, but would be something to get his teeth into in his rock and roll decline, which Edwyn thought must surely kick in by the time you reached forty. (How times have changed; today the world is full of creaky old rockers, not so much growing old gracefully as scarily.)

He talked of wildlife illustrators from the past that he admired: Archibald Thorburn, Audubon in America, and Edward Lear, whose cartoonist flights of fancy he loved too.

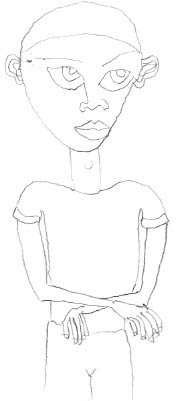

When I sat by his bed, silently numbering his lost accomplishments, I wondered what, if anything, it was possible to do about drawing. I provided him with materials while he was incarcerated in hospital, but he showed little or no interest at that time. Shortly before he left Northwick Park, he began to draw a cartoon man, possibly a self-portrait. A natural right-hander, he had to try with his left hand. When he came home, drawing this figure became part of his daily routine. I called him ‘The Guy’. I have about sixty versions of him. When I dug them out to show Edwyn, much later on, his laughing reaction was: ‘I’m mad, totally mad! Why? Oh dear!’

But I happily watched him slave away over The Guy for a few months. Something told me he was helping Edwyn’s brain to restore order, bringing certain things back into sharper focus. Like reciting lists of rock bands back in the Royal Free, repetition continued to be an important tool in memory retrieval.

One day, in late 2005, I gently suggested he set him aside and try a bird. Edwyn has an old AA Book of British Birds and from that he chose a wigeon. Then a teal. And a wren. A Canada goose. On and on – one, sometimes two a day. Each drawing named and dated. Edwyn consistently describes his early efforts as ‘crude’. He was not only trying to relearn the skill, but teach his alien left hand to do what only the right hand had been able to do. But the form and line are evident from the start and it was encouraging and thrilling to see how fast progress came. Inside, his talent for drawing was intact, and he knew it. This was the first of his lost gifts to return and it represented a great deal to Edwyn. It still does; he draws almost every day, unless events interrupt him. When we return home from a busy day and I want to flop out for an hour in front of some mindless TV, Edwyn invariably makes a beeline for his seat at the drawing table. It never represents hard work to him, even if it does require concentration. The standard he draws to now is quite breathtaking. No allowances for the right to left transfer need be made, although, ever the self-critic, he still sees himself as a long-term work in progress.

Drawing gave Edwyn hope, self-confidence, self-belief. In November 2008, he held his first ever exhibition, entitled ‘British Birdlife’ at the Smithfield Gallery in London. Here is something he dictated as an introduction to the exhibition, with a little help in extrapolation from me. But these are his own words:

Ornithology (birds) has fascinated me for a long time. I can’t remember when I didn’t love birds. When I was a boy, I could identify every British bird, most of them on the wing. I collected stuffed birds, too.

I think I was eight or nine when I found a fledgling greenfinch in the garden in Dundee. My neighbour called it Tweety Pie. A female. I kept it in a shoebox in my bedroom. It would tweet from 5am onwards, but I was too lazy to get up until about six or seven. I found a bird man, an expert, who told me to feed it with special food called Swoop. You mixed it with water. I fed it from my finger and she gobbled it up. Then I helped her to fly using the back of the Lloyd Loom chair and tempting her to me with the Swoop. When she flew off she would sometimes come back in to visit if I left the window open. And later she came back to have her first brood in the holly bush. A charming tale!

Drawing has been always been part of me, a passion. My mother and father are both artists. They met at Edinburgh Art School and my father went on to teach at art school. So I suppose I was surrounded by it growing up. When we formed the Postcard label in 1989 to put out Orange Juice Records, I would illustrate a lot of stuff for it, although we had another brilliant illustrator, Krysca. And as my music career went on, I’ve always drawn and designed.

I thought I would do a collection of bird illustrations when I retired from music. I loved Archibald Thorburn, a Victorian illustrator, particularly. I thought it would probably take about ten years, a nice little project.

I had a stroke, a brain haemorrhage, in 2005. I couldn’t say anything at all at first and I couldn’t read or write. I couldn’t walk to begin with. My right hand didn’t work. I’m right handed. So, no more guitar. The first time I held a pencil, I could produce a scribble, and that was it. I was in a confused state. Where do I start? I had to learn patience.

Gradually I took my pencil more and more. At first I drew ‘The Guy’ over and over again. It’s mad, totally mad! I have fifty drawings of him. He looks a bit like me. I can’t think why I did it now. Maybe I was stuck, but I think maybe he helped me.

Then I drew my first bird, a wigeon. It’s quite crude, but I was pleased with the result. Each day I drew at least one bird. I was tired back then, but my stamina has grown.

I could see my progress with each bird. Up, up, up. It’s encouraging.

Until recently I only liked to use very cheap notebook paper. I’m a creature of habit. But I’m now using posher cartridge paper. It changes your style.

When I draw there is no interference. Since my stroke I am interfered with quite a lot. And this is not to my taste, although I have been very co-operative. But when I draw, I am in charge and I don’t have a therapist or a wife bossing me about. I’m left to my own devices and in a world of my own. Drawing was the first skill to come back to me, so it meant the world. If I can draw, what else can I do?

My recovery began with my first bird drawing. And now I’m showing my drawings in an exhibition. I’m looking forward to seeing them like this. At the moment they sit in piles on my table. I’m back on board. The possibilities are endless!

Not only has Edwyn’s drawing ability come back to him, but his appetite for it is greater than it ever was. The challenge of learning to draw with his ‘unnatural’ hand seems to have fired his imagination. How amazing that as he struggled to overcome the limitations his illness imposed on so many areas of life, he had the enormous boost from knowing that this one thing was at least coming back, better and better each day. Improvement, and the potential for more of it, is where it’s at for Edwyn, and drawing gives him that satisfaction in spades.

•

SATURDAY 7 JANUARY 2006 arrived to burst our bubble somewhat. We were still in Helmsdale. At the end of an uneventful morning, Edwyn was drawing at the kitchen table. We had just finished an hour or so’s writing practice, quite a successful session. I was a few yards away, folding laundry. He uttered a short sound, of protest I thought, as I accidentally bumped the table. Then again. As I looked up, I saw him arch backwards stiffly, his eyes half-close and his whole body begin shaking violently. I rushed towards him, gathering him up, restraining him, reassuring him. I knew right away what it was: a fit, a seizure. This had been mentioned as a risk back in hospital but I had assumed, wrongly it would turn out, that at this distance of time, almost a year, the danger had passed. I called Will, urgently. He usually needs me to shout several times before he pays any heed, but I only needed to call twice. I hurriedly called out Sharon and Tommy’s number to him and, in spite of his alarm, he did everything I asked of him perfectly: call our friends, ask them to ring for an ambulance, explain that Dad is having a seizure. I couldn’t let Edwyn go in case he hurt himself, he was still bucking in my arms. I wanted Sharon or Tommy to talk to the emergency services; it would be easier for them to give clear directions. Soon after, the phone rang. It was the ambulance controller, looking to give me some instructions. By this time Edwyn had stopped fitting but was completely unconscious and breathing very hard. Tommy and Sharon arrived seconds later and helped me get him to the floor and into a more comfortable position. His hard breathing subsided. He gradually opened his eyes. Very disorientated, he was unable to speak or understand us.

The thoughts fly fast, the adrenalin races, the fear takes hold again. We couldn’t go back, please, please.

From the local hospital it was a twenty-minute dash for the ambulance. By the time they arrived Edwyn was more conscious and we lifted him onto his chair. The world was swimming into focus again. He smiled and tried to co-operate. He was able to walk into the ambulance with me. Tommy and Sharon follwed on with Will in the car. Ever practical, one of them brought our car, so we could all get back. In the back, the paramedic asked Edwyn some questions which he answered firmly, checking himself as he spoke: yes, I know this, I’m OK. His name, his date of birth, a few other things. I could see the relief I felt mirrored in his face.

At the local hospital, the Lawson in Golspie (where John Lennon was taken care of after his road accident in the Highlands, incidentally), Edwyn was desperate for the loo. When he emerged, we saw Will looking urgently for him. He spotted his Dad, on his feet, smiling.

‘Hiya son, I’m fine.’ Anxious to put him at ease, these were the signs we wanted to see. Normal reactions, speech, concern for his boy. Phew.

We saw an incredibly kind duty doctor, who was absolutely lovely to us. He explained the implications and suggested that Edwyn needed to be referred now to a neurologist. He offered him an overnight stay, which Edwyn graciously declined. Should another seizure occur, in the short term, he suggesed an admission to the regional hospital in Inverness for assessment, otherwise we must wend our way southwards and sort out a referral via our doctor in London. Chances of a repeat? No idea, nobody can say. Maybe soon. Maybe never.

•

OVER ONE OF Tommy’s homemade curries that evening, the shockwaves evaporated and Edwyn and I resolved to simply press on, deal with it and try not to worry.

A few days later we said goodbye to Helmsdale; on the one hand reluctantly, but knowing that we had issues to address, so, keen to get back to London, hopefully unscathed.

On the Glasgow stopover, however, Edwyn displayed the first signs that he hasn’t quite got off scot-free. He was as worried as I was about the implications of repeat seizures on his recovery, and began to display the symptoms of heightened anxiety. I knew the signs well. Until Edwyn’s illness, panic attacks were something I knew about but hadn’t been able to empathise with. In the last year, I had been introduced to this unpleasant side effect of shock, having had my own experience of delayed reaction. Not at all nice to see Edwyn go through it.