Released October 13, 1952 (U.K.); 82 minutes (U.S.); B & W; a Hammer Film production; an Exclusive Release (U.K.), a Lippert Presentation (U.S.); filmed at Hammersmith-Riverside Studios; Director: Sam Newfield; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Screenplay: Orville H. Hampton, from the BBC racho serial by Lester Powell; Director of Photography: James Harvey; Editor: James Needs; Art Director: Wilfred Arnold; Sound: William Salter; Production Manager: John Green; Assistant Director: Basil Keys; Dialogue Director: Patrick Jenkins; Camera: Moray Grant; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Hairdresser: Bill Griffiths; Casting: Michael Carreras; Music: Ivor Slaney; Conducted by: Muir Mathieson; Recorded by: London Philharmonic; U.S. Title: Scotland Yard Inspector; U.K. Certificate: A.

Misleading American title for Lady in the Fog.

Cesar Romero (Philip O’Dell), Lois Maxwell (Peggy), Bernadette O’Farrell (Heather), Geoffrey Keen (Hampden), Campbell Singer (Inspector Rigby), Alister Hunter (Sgt. Reilly), Mary Mackenzie (Marilyn), Frank Birch (Boswell), Wensley Pithey (Sid), Reed de Roven (Connors), Lloyd Lamble (Sorrowby), Peter Swanwiek (Smithers), Bill Fraser (Sales Manager), Lisa Lee (Donna), Lionel Harris (Alan), Betty Cooper (Dr. Campbell), Clair James (Miss Andrews), Katy Johnson (Mad Mary), Stuart Saunders (Policeman).

Philip O’Dell (Cesar Romero), an American reporter fog-bound in London, kills time in a pub with Heather (Bernadette O’Farrell), who is waiting for her brother. A bobby enters to call for an ambulance for a hit-and-run victim—her brother, Danny (Richard Johnson). Since Danny was often in trouble, Heather suspects murder; but when O’Dell takes her to Scotland Yard, both are dismissed. O’Dell decides to investigate the matter himself and traces Danny to Peggy’s Night Club and, after flirting with the owner (Lois Maxwell), gets an address from a waiter. When he enters Danny’s room, O’Dell is knocked unconscious and, after waking up, finds a tape recording.

Later, Danny’s girlfriend (Mary Mackenzie) takes O’Dell to film producer Chris Hampden (Geoffrey Keen), who occasionally employed Danny. O’Dell listens to the tape and gets valuable information, but stupidly erases it when he tries to play it for Heather. Following the lead, they go to Gladstone Asylum and interview Martin Sorrowby (Lloyd Lamble). Sorrowby, Hampden, and a mysterious “Margaret” were being blackmailed by Danny for murdering an inventor during the war after stealing his secret for a new carburetor. O’Dell inspects the bombed-out lab, and is attacked by Connors (Reed de Raven), Hampden’s henchman, while Hampden and his wife, Margaret—Peggy—kidnap Heather. While being chased by O’Dell, Hampden falls to his death, and Margaret dies in a car crash while escaping.

“I had just completed a film in India—The Jungle—for Lippert,” Cesar Romero told the authors (November, 1992), “and I stopped off in London on my way home. I was met at the airport by someone from Hammer who informed me that Lippert had made a deal for me while I was in the air! As a freelance actor, I’ve made films all over the world, so this was nothing new for me. Everyone I worked with was pleasant—especially James Carreras—a real gentleman and a nice guy. Sam Newfield was easy to work with under the conditions of a quick schedule. The details of the film are forgotten, but I sure remember the good time I had.”

Lady in the Fog began production on March 24, 1952, with an American star, writer, and director, plus some concerns. The Kinematograph Weekly (September 11, 1952) reported that, “Doubt as to how the British technicians might adapt themselves to American methods was dispelled on the first day of shooting when, with twenty-five camera setups, no fewer than nine minutes of quality screen time was put in the can.” The picture finished on schedule, despite the original misgivings, was trade shown on September 10, 1952, and released on October 13, to mixed reviews. The British Film Institute’s Monthly Bulletin (November): “Routine mystery”; and The Kinematograph Weekly (September 11): “Despite some confusion, it puts plenty of variety and no little kick into its dizzy surface action.”

How much one likes this film depends on one’s liking for Cesar Romero. His light touch and engaging personality make many of the comedy scenes work well, especially with Katie Johnson as a lunatic at the asylum. Most of the movie, though, leaves the viewer in a fog as its many disparate parts don’t add up to much.

Released January 26, 1953 (U.K.), December, 1952 (U.S.); 6645 feet; 74 minutes (U.K.), 71 minutes (U.S.); B & W; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Films Release (U.K.), a Lippert Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios, England; Director: Pat Jenkins; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Director of Photography: Walter Harvey; Editor: Maurice Rootes; Music: Ivor Slaney; the London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by: Marcus Dodds; Art Director: J. Elder Wills; Sound: William Salter; Production Manager: John Green; Assistant Director: Ted Holliday; Camera: Moray Grant; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Casting Director: Michael Carreras; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Hair Stylist: Pauline Trent; U.K. Certificate: U.

Dane Clark (Jim Forster), Kathleen Byron (Pat), Naomi Chance (Susan Willens), Meredith Edwards (Dave), Anthony Forwood (Peter Willens), Eric Pohlmann (Arturo Colonna), Enzo Coticchia (Angelo Colonna), Julian Somers (Lucasi), Anthony Ireland (Farning), Thomas Gallagher (Sam), Max Bacon (Maxie), Mona Washbourne (Miss Minter), Jane Griffith (Janey Greer), Richard Shaw (Louis), George Pastell (Jaco Spina), Martin Benson (Tony), Eric Boon (The Boxer), Felix Osmond (Boxing Promoter), Percy Marmont (Lord Hortland), Robert Adair (Engles), Mark Singleton (Waiter—Jack of Spades), Peter Hutton (Roger Bowen), Andre Mikhelson (El Greco), Paul Sheridan (The Croupier), Robert Brown (Waiter—Maxie’s), David Keir (The Gambler), Irissa Cooper (The Tart), Laurie Taylor (Shadow), Valencia Trio (Adagio Act).

Jim Forster (Dane Clark), a recovering alcoholic and habitual gambler, arrives in Britain after serving a prison term in America for manslaughter. Living by luck and his wits, he becomes the owner of a nightclub and a race horse, both named “The Jack of Spades.” Determined to better himself socially, Forster begins to associate with the “upper class,” including Lady Susan Willens (Naomi Chance), daughter of Lord Hortland (Percy Marmont). He hastily ends his affair with Pat (Kathleen Byron), a dancer at his club, who does not handle the rejection well. Forster also alienates his club manager Dave (Meredith Edwards), who is unimpressed with his boss’s social climbing.

Forster’s luck turns bad when he refuses to sell the club to a gang led by Arturo (Eric Pohlmann) and Angelo Colonna (Enzo Coticchia), who declare war. After being swindled on a stock deal suggested by Lord Hortland, Forster sells the club to pay his debts. When Dave is murdered by the Colonnas, who blame Forster for a series of police raids, Jim seeks revenge. He is wounded in a shootout, and, as he staggers into the street, is run down by Pat in her car.

Dane Clark enjoyed working for Hammer so much he stayed on to do two more films.

Dane Clark’s successful 1940s film career began to sag in the fifties. He found work in Britain in Highly Dangerous (1951), which brought him to Hammer’s attention, and he became the first Hollywood star to appear in three Hammer films. Anthony Hinds had originally planned to have American Sam Newfield direct The Money, the film’s original title. He had just completed Lady in the Fog, and Hammer was pleased with his efficiency. However, his employment would have violated a labor quota which placed a cap on the number of foreign directors permitted on British films during any given year. The company got permission to employ a British “co-director” who would be paid the minimum and have his name in the credits. Hammer also wanted the expertise of American directors, who were, in general, less methodical than their British counterparts. With the money saved by shorter schedules, Hammer could invest more in future projects. In April, 1952, the company made an official request to the Ministry of Labor to be permitted to have an American director on their payroll on a permanent basis.

The Gambler and the Lady began production on May 19, 1952, and concluded on June 16, with location work done at Windsor Castle and the Ascot Race Course. The directional credit was given to Pat Jenkins on British prints, and Sam Newfield got co-director billing in America. Making things more confusing, Today’s Cinema (June 16) gave Terence Fisher the credit! Oddly, no one received a screenplay credit. Later that year, restrictions against foreign directors were relaxed. A trade show was held on January 6, 1953, and the film went into its U.K. release on January 26—a month after premiering in America. Reviews in both countries were discouraging. The Monthly Film Bulletin (January, 1953): “Dane Clark deserved something rather better”; The Motion Picture Exhibitor (December 17, 1952): “A fair amount of action and suspense”; and The Kinematograph Weekly (November 13, 1952): “Lacks fire and purpose.” Despite the presence of a well-cast Hollywood star, The Gambler and the Lady failed to please.

Released March 16, 1953 (U.K.); 73 minutes; B & W; 7035 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Release (U.K.), United Artists (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios and on location in London; Director: Terence Fisher; Producers: Michael Carreras, Alexander Paal; Screenplay: Paul Tabori, Terence Fisher, from Elleston Trevor’s Queen in Danger; Director of Photography: Reginald Wyer; Music: Doreen Carwithen, played by Royal Philharmonic; Conductor: Marcus Dodds; Art Director: J. Elder Wills; Sound Recordist: Jack Miller; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Production Manager: Victor Wark; Assistant Director: Bill Shore; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Makeup: D. Bonnor Morris; 2nd Assistant Director: Aida Young; 3rd Assistant Director: Vernon Nolf; Stills: John Jay; Focus: Manny Yospa; Editor: James Needs; Assistant Editor: Jimmy Groom; U.K. Certificate: A; U.S. Title: Man in Hiding.

Paul Henreid (Bishop), Lois Maxwell (Thelma), Kieron Moore (Speight), Hugh Sinclair (Jerrard), Lloyd Lamble (Frisnay), Anthony Forwood (Rex), Bill Travers (Victor), Mary Laura Wood (Susie), Kay Kendall (Vera), John Penrose (DuVancet), Liam Gaffney (Douval), Conrad Phillips (Barker), John Stuart (Doctor), Anna Turner (Marjorie), Christina Forrest (Joanna), Arnold Diamond (Alphonse), Jane Welsh (Laura), Geoffrey Murphy (Plainclothesman), Terry Carney (Detective), Sally Newland (Receptionist), Barbara Kowin (later Shelley) (Fashion Commere).

Having been convicted of committing a murder while insane, Speight (Kieron Moore) has escaped from prison and is on the loose in London. His wife Thelma (Lois Maxwell) is terrified. She is now the lover of Victor Tasman (Bill Travers) whose name she has taken. Publisher Maurice Jerrard (Hugh Sinclair), for whom she is an editor, is also concerned. Hugo Bishop (Paul Henreid), a private detective, attempts to find Speight before the police and stakes out the murder scene near St. Paul’s Cathedral. He finds Speight, and the two form an uneasy alliance, but Bishop cannot determine the cause of the murder.

As he investigates, Bishop learns of the Speights’ unhappy marriage and that the victim may have been Speight’s mistress. He also learns that Speight wishes Thelma well in her new life and begins to suspect Jerrard. Bishop arranges for the principals to meet at a party—along with Inspector Frisnay (Lloyd Lamble). When Thelma spots Speight, her reaction leads to his arrest. He denounces Jerrard, who, with help from Bishop, implicates himself in front of Frisnay. Jerrard breaks free and is chased by Bishop through the streets to the original murder scene where he falls to his death. He had framed Speight, after killing the girl, so he could move in on Thelma. Speight decides to leave England, Thelma and Victor plan to marry, and Bishop may settle down with his secretary Vera (Kay Kendall).

Mantrap has the look of the opener to a series that never materialized. Hammer was certainly not against series characters, and this one might have worked, due mainly to the Nick and Nora Charles (The Thin Man, 1934) relationship between Hugo and Vera. Paul Henreid, not noted for his light comedy talents, is surprisingly engaging as Hugo Bishop, P.I. Henreid was on the fringe of the Hollywood “blacklist,” and after he moved to England, his career never regained its momentum. Kay Kendall soon became a big star in Genevieve (1953), married Rex Harrison, but died at age 33 of leukemia. Kieron Moore also shines as the tormented fugitive and made the most of his limited screen time. But, despite the fine cast, Mantrap has too much talk, and too little action. This was one of the few films on which Terence Fisher took a writing credit, but like most directors, he usually had a hand in the script. Although his direction is fine, he must share the blame (with Paul Tabori) for the talkfest.

Mantrap was cameraman Len Harris’ first Hammer film. “I had seen The Last Page at my local cinema,” he told the authors (December, 1993),

and I thought it was a well made little film. I had been a camera operator for years, and thought I’d like to work for this Hammer company. I went around, and the next thing I knew I was on Mantrap! I stayed with Hammer for the next ten years and loved every minute of it. As the camera operator, you work very closely with the director—more so than does the lighting cameraman. A director like Terence Fisher lets you go on with it yourself. He has his job, you have yours, and he lets you do it. Terry always, of course, had the final word, but he always listened. I was made to feel right at home at Bray. They were a wonderful group of people—when you worked for Hammer, there were no outsiders—only family. I thought Mantrap was a respectable picture, but seeing it now, I was confused by the plot—far too many twists!

Paul Henreid arrived in London on June 12, 1952, and filming began four days later. Reviews, following a March 1, 1953, trade show, were tepid. The Cinema (March 4): “The climax is effective in its contrived suspense”; The Motion Picture Herald (November 14): “The writers were so intent on mystifying the audience they forgot to include any cohesion in their story”; and The Kinematograph Weekly (March 5): “The variety of cunningly contrasted backgrounds put a healthy complexion on the crowded, slightly novelettish plot.”

Mantrap was another competently made but uninspired thriller—a type of film quickly becoming a Hammer specialty.

Released May 25, 1953 (U.K.), May 15, 1953 (U.S.); 81 minutes; B & W; 7332 feet; a Hammer Film Production; Released through Exclusive (U.K.), Astor Pictures (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Terence Fisher; Producers: Michael Carreras, Alexander Paal; Screenplay: Paul Tabori, Terence Fisher, based on William F. Temple’s novel; Director of Photography: Reg Wyer; Editor: Maurice Rootes; Music: Malcolm Arnold; Played by: Royal Philharmonic, conducted by Muir Mathieson; Art Director: J. Elder Wills; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Sound Recordist: Bill Salter; Dialogue Director: Mora Roberts; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Makeup: D. Bonner-Moris; Assistant Director: Bill Shore; Hair Stylist: Nina Broe; Production Manager: Victor Wark; U.K. Rating: A.

Barbara Payton (Lena/Helen), James Hayter (Dr. Harvey), Stephen Murray (Bill), John Van Eyssen (Robin), Percy Marmont (Sir Walter), Jennifer Dearman (Young Lena), Glyn Dearman (Young Bill), Sean Barrett (Young Robin), Kynaston Reeves (Lord Grant), John Stuart (Solicitor), Edith Saville (Lady Grant).

Robin (John Van Eyssen) and Bill (Stephen Murray) have been in love with Lena (Barbara Payton) since childhood. When she returns to their village, after spending several years in America, Lena finds the pair engaged in a strange research project. The men are trying to change energy into matter and, after two years of failure, Robin’s father, Sir Walter (Percy Marmont) decides to cut their funding. They are saved by their old friend, Dr. Harvey (James Hayter), who sells his practice to bail them out. Finally, they succeed in being able to duplicate any object exactly, but find themselves driven apart by Lena.

Sir Walter learns of their success and insists they turn their project over to the government, which they refuse to do. At a celebration banquet, Lena and Robin announce their engagement, crushing Bill who spends all of his time in the lab. After successfully copying a rabbit, he is ready for an insane step—duplicating Lena. Incredibly, she consents.

Bill and “Helen” leave on holiday, and all seems well until he realizes the experiment was too successful—she also prefers Robin. Distraught, Bill attempts to erase “Helen’s” memory and again is too successful—she becomes a zombie. A short circuit causes a fire in the lab, destroying the unhappy couple, as Lena escapes unharmed.

This minor science fiction drama was poorly received, but was a major step toward Hammer’s as yet unplanned Frankenstein film. Filmed over a five-week period during August and September, 1952, the movie’s main selling point was Hollywood “bad girl” Barbara Payton. At a reception in her honor, James Carreras (Kinematograph Weekly, July 31, 1952) announced the company’s plans for the coming year. He intended to create two separate teams that would alternate production, resulting in almost continuous filming. Each team would include a producer, director, production manager, and cutting staff. One was to be headed by Michael Carreras, the other by Anthony Hinds, with a maximum break of two weeks between films.

Terence Fisher, taking a rare screenplay credit, adapted (with Paul Tabori) William F. Temple’s novel for his first science fiction film—a genre with which he had little success. During this period, the typical science fiction picture was concerned with space travel, giant insects, if possible, or both. The Four Sided Triangle, though, belonged to the “cerebral” branch of the genre, along with Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), although it wasn’t in the same league as this superior film. Typically, Fisher was more interested in the effects of the duplicating experiment than in the mumbo-jumbo of its mechanics, which was at variance with the bulk of this type of film. As a result, The Four Sided Triangle is interesting rather than exciting. Like many Hammer films of the early fifties, it never comes to life despite often threatening to do so.

This laboratory set could have used Bernard Robinson’s magic touch in this scene from Hammer’s Four Sided Triangle (photo courtesy of Ted Okuda).

Most of the film’s little excitement was related to Miss Payton, who had gained all the bad publicity one would want due to a fist fight between actors Tom Neal and Franchot Tone over her “favors.” She eventually married the battered Tone—it lasted one month. The Picture Post (August 30, 1952) ran a provocative shot of her wearing a bathing suit, something she did better than acting. Despite her tawdry background (or due to it), she was mobbed by autograph seekers during a location shoot at Weymouth. Her performance is passable, but the film cried for a more charismatic star. The same is true of the male leads.

Reviews were condescending following the film’s May, 1953, release. The British Film Institute’s Monthly Bulletin (June, 1953): “A tedious melodrama, flatly directed, written, and played”; The New York Times (May 16, 1953): “An exploitation picture opening at the Rialto, and a better home for it couldn’t be found.” The Rialto was a notorious theatre specializing in films like, well, The Four Sided Triangle. Hammer didn’t give up on the genre, following this one with Spaceways. Sixteen films later they got it right with The Quatermass Xperiment.

The Flanagan Boy

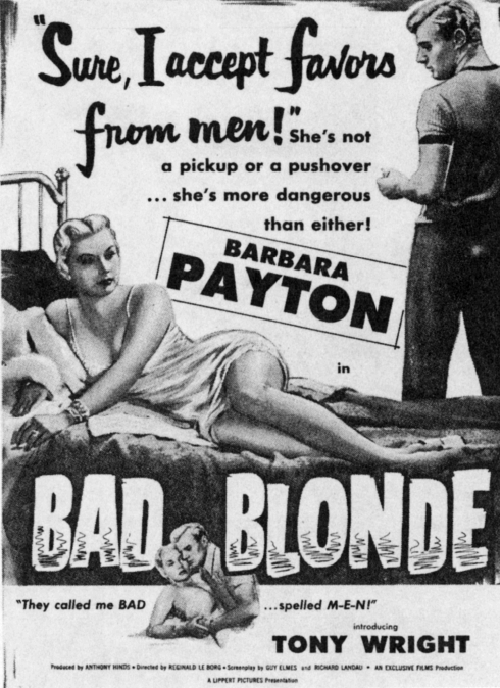

Released July, 1953 (U.K.), April, 1953 (U.S.); 81 minutes; B & W; 7313 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Release (U.K.), a Lippert Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Reginald LeBorg; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Screenplay: Guy Elmes; Adaptation: Richard Landau, based on Max Catlos’ novel; Director of Photography: Walter Harvey; Music: Ivor Slaney; Editor: James Needs; Camera: Len Harris; Production Manager: John Green; Art Director: Wilfred Arnold; Dialogue Director: Patrick Jenkins; Assistant Director: Jimmy Sangster; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Sound: Bill Salter; U.S. Title: Bad Blonde; U.K. Certificate: A.

Barbara Payton (Lorna), Frederick Valk (Vacchi), John Slater (Charlie), Sidney James (Sharkey), Tony Wright (Flanagan), Marie Burke (Mrs. Vecchi), Selma Vas Dias (Mrs. Corelli), George Woodbridge (Inspector), Enzo Coticchia (Mrs. Corelli), Bettina Dickson (Barmaid), Joe Quigley (Kossov), Tom Clegg (Fighter), Chris Adcock, Bob Simmonds (Booth Men), Roy Catthouse (Coloured Fighter), Ralph Moss (Kossov’s Second), Laurence Naismith (Barnes).

Film noir, Hammer style: The Flanagan Boy was retitled Bad Blonde for the U.S. market.

After winning a carnival boxing match, sailor Johnny Flanagan (Tony Wright) is spotted by Sharkey (Sidney James) as having potential and is introduced to Charlie Sullivan (John Slater), a trainer. Giuseppi Vecchi (Frederick Valk), agrees to finance Johnny over the objection of his sultry wife Lorna (Barbara Payton). Johnny trains at Vecchi’s estate, and he soon becomes involved with Lorna. His training goes badly, and he is ashamed of his conduct but is unable to break free. Before Johnny’s big bout with Lou Koss (Joe Quigley), Sharkey confronts Lorna to no avail—Johnny is brutally beaten the next night, distracted by Lorna in the audience.

Vecchi wants to drop Johnny, but allows him to continue living on the estate. When Lorna announces her pregnancy, Vecchi is ecstatic—but Johnny knows that Giuseppi is not the father. The pregnancy pushes Johnny over the edge and, goaded by Lorna, he drowns Giuseppe. Vecchi’s mother arrives from Italy and suspects the truth and forces Lorna to admit to faking the pregnancy. Johnny wants to confess to the murder, but is poisoned by Lorna who arranges his death to look like a suicide. Sharkey and Charlie are not taken in and turn her over to the police.

Bad girl Barbara Payton struts her stuff in The Flanagan Boy (photo courtesy of Ted Okuda).

This is Hammer’s best attempt at a Hollywood style film noir and is reminiscent of James M. Cain’s classic The Postman Always Rings Twice, with its triangle of a belligerent young stud, wild young wife, and her unattractive husband. Barbara Payton’s white bathing suit is almost a perfect match to Lana Turner’s in the 1946 version, leaving little doubt of Hammer’s intentions.

Filming began on September 25, 1952, and was immediately held up for several days when Tony Wright injured an ankle during a boxing scene. Wright was very convincing as a fighter, having been an amateur in the British Navy and receiving coaching from Len Harvey, a former British heavyweight. This was Wright’s first film role, although he did have repertory experience in South Africa. Payton, appearing in her second Hammer film of the year, brought to The Flanagan Boy her main asset—a sullen sensuality that just might have been good acting. She also had a well-earned “bad girl” image that was perfect for the character. Lippert provided Hammer with Payton and almost certainly with Reginald LeBorg, who had been directing in America since the early forties (The Mummy’s Ghost, 1944). The production closed on October 19, 1952, and The Flanagan Boy was trade shown on June 20, 1953, and released in July. Reviews concentrated on the film’s sexual content. The Cinema (June 24): “It is the sex angle that dominates. Action offering for tolerant tastes”; Variety (April 28): “Le Borg seemingly directed Anthony Hinds’ production to accent only the script’s sex angles”; The British Film Institute’s Monthly Bulletin (August): “A lurid little melodrama”; and The Kinematograph Weekly (June 25): “Realistic fight sequences enable it to conceal its lurid structure.”

These reviews were forerunners of those that would assault many a Hammer film in the near future, as The Flanagan Boy was the company’s first picture to be attacked on “moralistic” grounds, with “lurid” an often used description. Seen today, this aspect is hardly noticeable; and what’s left is a tough, entertaining melodrama with strong performances from both leads.

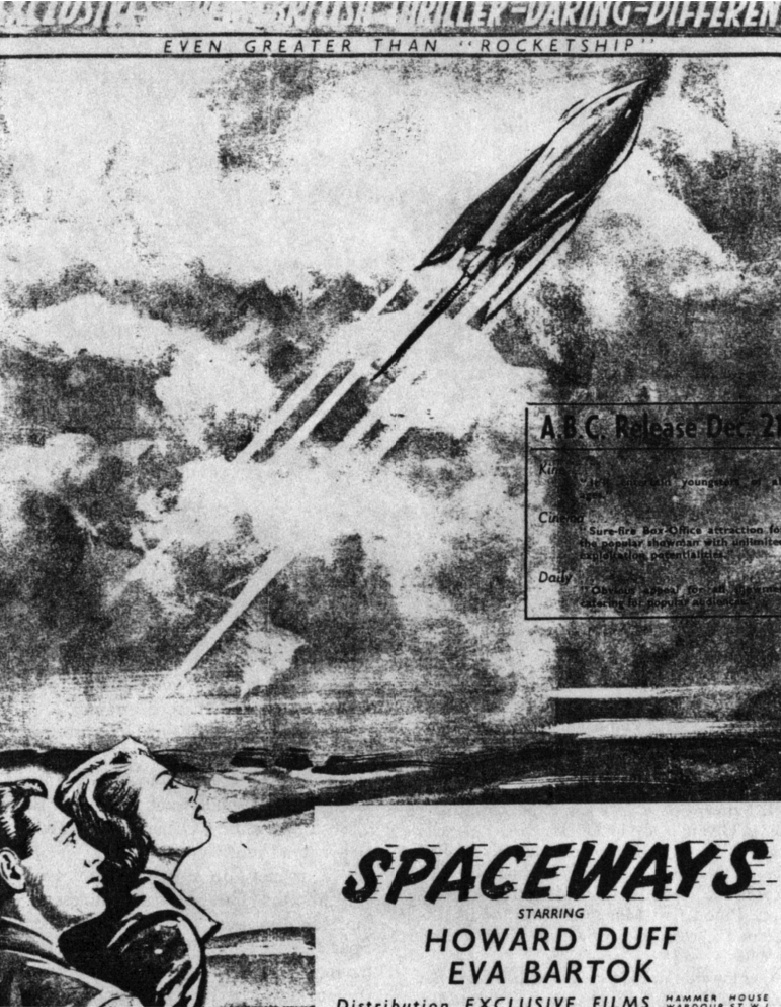

Released December 21, 1953 (U.K.), July, 1953 (U.S.); 76 minutes (U.K.), 74 minutes (U.S.); B & W; 6879 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Films Release (U.K.), a Lippert Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Paul Tabori, Richard Landau, based on the BBC radio play by Charles Eric Maine; Director of Photography: Reginald Wyer; Editor: Maurice Rootes; Camera: Len Harris; Art Director: J. Elder Wills; Music: Ivor Slaney, played by The New Symphony Orchestra; Sound: Bill Salter; Sound System: RCA; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Makeup: D. Bonnor-Moris; Dialogue Director: Nora Roberts; Hairdresser: Polly Young; Special Effects: The Trading Post Ltd.; Process Shots: Bowie, Margutti, & Co., Ltd.; Production Manager: Victor Wark; Assistant Director: Jimmy Sangster; U.K. Certificate: U.

Inspector Smith (Alan Wheatley) questions his prime suspect Dr. Mitchell (Howard Duff) in Hammer’s Spaceways (photo courtesy of Ted Okuda).

Howard Duff (Stephen Mitchell), Eva Bartok (Lisa Frank), Andrew Osborn (Philip Crenshaw), Anthony Ireland (General Hays), Alan Wheatley (Dr. Smith), Michael Medwin (Toby Andrews), David Horne (Minister), Cecile Chevreau (Vanessa Mitchell), Hugh Moxey (Colonel Daniels), Philip Leaver (Dr. Keppler), Jean Webster-Brough (Mrs. Daniels), Leo Phillips (Sgt. Peterson), Marianne Stone (Mrs. Rogers).

Aiding the British with their rocket experiments at the Deanfield Space Center is American scientist Stephen Mitchell (Howard Duff). His wife Vanessa (Cecile Chevreau) is bored by the strict security and lack of social life, and is having a clandestine affair with Mitchell’s colleague Dr. Philip Crenshaw (Andrew Osborn), who is secretly a spy for a foreign power.

A rocket fails to return from a test at the time that Crenshaw and Vanessa inexplicably disappear from the high-security Space Center, and Mitchell is suspected of having placed his wife and her lover aboard the rocket. Mitchell and Dr. Lisa Frank (Eva Bartok), the project’s chief mathematician, are in love. In order to clear himself, Mitchell offers to go up in another rocket to locate the first one, which should be floating in space. Lisa secretly replaces another scientist (Michael Medwin) who volunteered to go along with Mitchell.

Dr. Smith (Alan Wheatley), a top agent from military intelligence, succeeds in tracking down and arresting Crenshaw, who killed Vanessa rather than leaving her alive to testify against him. The news arrives at the Space Center too late to prevent the takeoff of the second rocket. Mitchell and Lisa are in space when they learn via radio what has transpired, but rather than abandon the mission, they opt to attempt to retrieve the stranded space capsule. The instruments freeze up and Mitchell and Lisa appear to be doomed, but Mitchell finally succeeds in freeing the emergency controls and the capsule begins to level off. Lisa radios in that they will be returning home.

The studio’s first outer space melodrama is a dismal affair.

Most Hammer films turned a profit, but Exclusive’s release of the American made Rocketship X-M (1950) did far better than the company could have imagined. Mindful of its audience reactions, Hammer decided to produce their own space adventure, although Spaceways was more murder mystery than science fiction. Filming began on November 17, 1952. The film was to be completed on December 19, but, due to Eva Bartok’s throat surgery, the schedule was extended another month. Michael Carreras (Little Shoppe of Horrors 4) was not in favor of making the picture. “The budget was the same as it would have been if it was about two people in bed—a domestic comedy.” A factor in the film being made was the money Hammer received from the Eady Fund. Begun in September, 1950, Eady was financed by a tax on cinema tickets which was then made available to studios who wanted to increase their budgets or who needed backing after a film “flopped.” Due to Eady, Hammer was able to increase its budgets by 50 percent. Even so, Spaceways was budgeted far less than was required and looked it. James Carreras also wanted Eady money to build two new stages at Bray, which now had sixty-eight permanent employees.

Len Harris recalled for the authors (December, 1993): “Terence Fisher wanted some quick, cheap, and easy camera effects for when the rocket was launched. The only thing I could think of was to free float the camera and let Harry Oakes shake it while I tried to get something on film. Elaborate effects, Hammer style! Actually, it worked pretty well and didn’t cost a thing. Terry always asked for advice on matters like this. Not that it’s a big thing, but many directors wouldn’t ‘lower’ themselves. Hammer was very much a cooperative concern—no one pulled rank. Terry was always interested in other people’s ideas.”

Unfortunately, audiences and reviewers expect—and deserve—more than this in a science fiction movie; and, following Spaceways’ December 21, 1953, release, neither were impressed. The Monthly Film Bulletin (December): “A dull and shoddy affair”; The Kinematograph Weekly (June 25): “Artfully colored by pseudo scientific jargon and detail”; Motion Picture Exhibitor (July 15): “On the slow side”; and Variety (July 8): “Direction is extremely methodical.” Advertised as Britain’s first space adventure, Spaceways has little to recommend it. The talk-test film betrays its radio origins and is hampered by cheap sets, stock footage, an unexciting hero, and a lack of action. Hammer would do much better with the Quatermass series.