Released August 9, 1954 (U.K.), November, 1954 (U.S.); 80 minutes; B & W; 7229 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Release (U.K.), Lippert (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Michael Carreras, based on George Sanders’novel; Director of Photography: Jim Harvey; Editor: Bill Lenny; Production Manager: Jim Sangster; Art Director: J. Elder Wills; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Sound Camera Operator: Don Alton; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Hair Stylist: Eileen Bates; Sound Mixer: Sid Wiles; Assistant Director: Jack Causey; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Wardrobe Mistress: Molly Arbuthnot; Furs by Molino; Music: Leonard Salzedo; Music Supervisor: John Hollingsworth; U.K. Certificate: A; U.S. Title: The Unholy Four.

William Sylvester (Vickers), Paulette Goddard (Angie), Patrick Holt (Crandall), Paul Carpenter (Saul), Alvys Maben (Joan), Russell Napier (Treherne), David King Wood (Sessions), Pat Owen (Blonde), Kay Callard (Jenny), Jeremy Hawk (Sgt. Johnson), Jack Taylor (Brownie), Kim Mills (Roddy), Owen Evans (Redhead), Philip Lennard (Medical Examiner).

Patrick Holt, Joan Merrill, and Paul Carpenter discuss William Sylvester’s unwelcome return in The Stranger Came Home.

Philip Vickers (William Sylvester) returns to his country estate after being missing for three years, arriving during one of his wife Angie’s (Paulette Goddard) frequent parties. Angie is off with a man, and her secretary Joan (Alvys Maben) is openly hostile. Vickers had been on holiday in Portugal with Bill Saul (Paul Carpenter), Job Crandall (Patrick Holt), and Harry Bryce. One of the trio clubbed him from behind and left him for dead, his memory gone. All three are present at the party and are interested in Angie. Bryce’s body is found in the boathouse, and Inspector Treherne (Russell Napier) arrives to investigate.

Sessions (David King Wood), Vickers’ accountant, and Crandall, his business manager, have been defrauding him, and during a quarrel, Sessions is killed. Crandall decides to confess to Bryce’s murder also, to take the heat off Angie who is a suspect. When Trehane arrests Angie, Joan tries to protect her by implicating Vickers. When Saul arrives for a small dinner party, he murders Joan, setting up Vickers to take the blame. Vickers tells Saul that he killed Angie to get his reaction, and he is attacked. Vickers disarms Saul and beats a confession to the murder out of him—and Saul’s admission to the assault in Portugal. All of the crimes were committed to get Angie for himself.

This dull, confusing film marked the end of Hollywood star Paulette Goddard’s career which began in 1929. The Stranger Came Home was her second British picture, following An Ideal Husband (1948), and her return to the U.K. was treated as a major event. Production began on January 4, 1954, based on a novel by George Sanders, Hollywood’s resident cad. It’s too bad he wasn’t in the film as well.

Michael Carreras tries his hand at adapting a novel for the screen.

The Stranger Came Home was trade shown at the Hammer theatre on July 14, 1954, and was released on August 9 to unimpressive reviews. The Kinematograph Weekly (July 22, 1954): “There are no big thrills”; the British Film Institute’s Monthly Bulletin (September): “Almost incomprehensible”; Variety (September 29): “Direction of Terence Fisher is plodding until a windup fight”; The New York Times (November 20): “A third rate British whodunit.” As so often happened during this period, Fisher—justifiably—received most of the blame. Although the premise, production values, and acting are acceptable, the film is boring and slow—and that’s the director’s fault. Fortunately, Hammer saw something in Terence Fisher despite his poor notices. Len Harris told the authors (December, 1993), “Terry began his career as an editor—many good directors do. He was a very dedicated man. There was no wasted film—Terry was an editor’s delight. He always knew what he wanted before he shot it.” Fisher himself noted (Cinefantastique, Vol. 4, No. 3), “My career had been attempting to find a line of direction I was good at.”

There would be no second chance, though, for Paulette Goddard. She retired after completing the film and made only one film appearance since in Time of Indifference (1964), which would serve as a review of The Stranger Came Home.

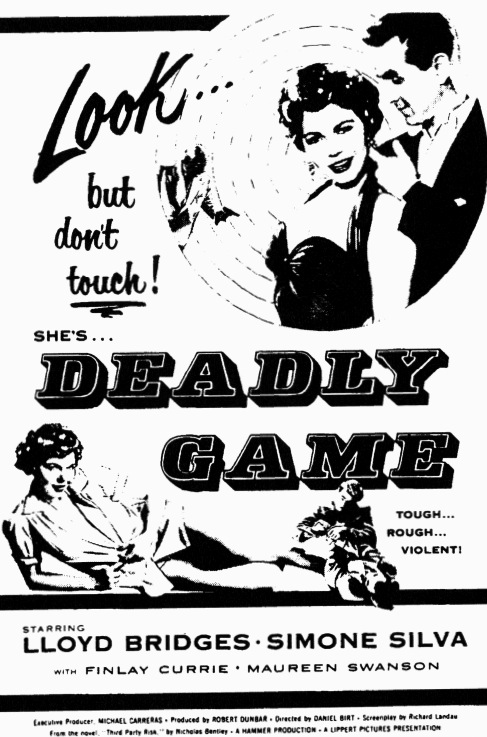

Third Party Risk

Released January, 1955 (U.S.), April 4, 1955 (U.K.); 70 minutes (U.K.), 63 minutes (U.S.); B & W; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Films Release (U.K.), a Lippert Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios, England, and on location in Spain; Director: Daniel Birt; Producer: Robert Dunbar; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Daniel Birt, Robert Dunbar, based on a novel by Nicholas Bently; Director of Photography: James Harvey; Editor: James Needs; Music: Michael Krein; Art Director: J. Elder Wills; Sound: Sid Wiles; Production Manager: Jimmy Sangster; Assistant Director: Jack Causey; Camera: Len Harris; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Wardrobe: Molly Arbuthnot; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Hair Stylist: Eileen Bates; Sound Camera: Don Alton. U.S. Title: Deadly Game; U.S. Television Title: Big Deadly Game; U.K. Certificate: A.

Lloyd Bridges (Philip Graham), Finlay Currie (Darius), Maureen Swanson (Lolita), Simone Silva (Mitzi Molnar), Ferdy Mayne (Maxwell Carey), Peter Dyneley (Tony Roscoe), Roger Delgardo (Gonzales), George Woodbridge (Inspector Goldfinch), Leslie Wright (Sgt. Ramsey), Mary Parker (Mrs. Zeissmann), Seymour Green (Rope-Soles), Toots Pounds (Lucy), Patrick Westwood (Porter), Russell Walters (Dr. Zeissmann).

While vacationing in Spain, author Philip Graham (Lloyd Bridges) meets a wartime friend, Tony Roscoe (Peter Dyneley). He introduces Graham to Darius (Finlay Currie), a London financier, Lolita (Maureen Swanson), his niece, and Mitzi (Simone Silva) and Maxwell Carey (Ferdy Mayne). Graham is attracted to Lolita, but Tony whisks him away when he needs a ride to the airport. Graham is then asked to drive Tony’s car to London and deliver an envelope. At Tony’s London apartment, Graham finds Mitzi burning some letters—and, later, his friend’s corpse on the floor beside a roll of microfilm. He finds more microfilm inside the envelope, and discovers that it contains a valuable chemical formula stolen from Dr. Zeissmann (Russell Walters).

After eliminating Mitzi as the killer, Graham suspects her husband who knows about the stolen microfilm. Carey sets a trap for Graham in a warehouse, but, Maxwell himself dies in a fire. When Graham goes to see Lolita, he learns that she and Darius have returned to Spain. He follows them, and with the help of the village police chief (Roger Delgado), proves that Darius masterminded the international plot.

The growing popularity of CinemaScope, Technicolor, and television was beginning to have a negative effect on small independent producers like Hammer. The company began to experiment with filming in foreign locations to ward off sagging ticket sales, but to little avail. Hammer’s lucrative agreement with Robert Lippert was also about to end.

Although James Carreras made plans to produce eight more features in 1955, Third Party Risk was the last picture released in America through Lippert. The film began production on February 15, 1954, under the direction of Daniel Birt, who died a few months after its completion at age 48.

Len Harris recalled (August, 1993) a harrowing incident while filming the fight scene between Lloyd Bridges and Ferdy Mayne. “We did the fire scene in an old barn which had been built for another picture. Daniel Birt, Jimmy Harvey, and I were in a gantry when the staircase was set on fire. When Birt yelled ‘Cut!,’ the firemen rushed in and put out the fire, but the smoke drifted up to the gantry, and we were suffocating. Usually, I would try to figure out an escape before I needed it, just in case. I kicked out the slats of the barn wall for some air, but the three of us were pretty sick. No one really thought of the possible danger. Because Hammer’s new sound stages were unavailable, interiors for Third Party Risk were filmed in the Old House. We built sets within rooms, especially the big ballroom. We had put in a certain amount of sound proofing, but it was far from perfect. In the silent days, most British films were shot in old houses—it was sound that caused the problems.” Recalling in-house Art Director J. Elder Wills, Harris said, “He was an ‘old boy’ at Hammer—and a very interesting character. During World War II, he was a colonel in the camouflage unit, put down on the Normandy beach to take soil samples to make sure that the tanks wouldn’t bog down during the invasion. He was dressed like a peasant, collecting soil in a can! Anthony Hinds took his pseudonym—John Elder—from him. Wills was, I believe, a cousin of Will Hammer.”

Len Harris, James Harvey, and director Daniel Birt nearly burned to death during the making of Hammer’s Third Party Risk (retitled Deadly Game for the U.S. market).

Third Party Risk was trade shown at the Hammer Theatre on March 22, 1955, but had its American release in January. The picture was released in the U.K. on April 4 to mixed reviews and slow box office. Today’s Cinema (March 23): “The improbable adventures sweep along excitingly enough”; The Monthly Bulletin (May): “Unimaginative direction and routine performances”; and The Kinematograph Weekly (March 24): “The trimmings accentuate rather than conceal its poverty of imagination.” Third Party Risk proved that it took more than location filming to lure audiences from their TVs.

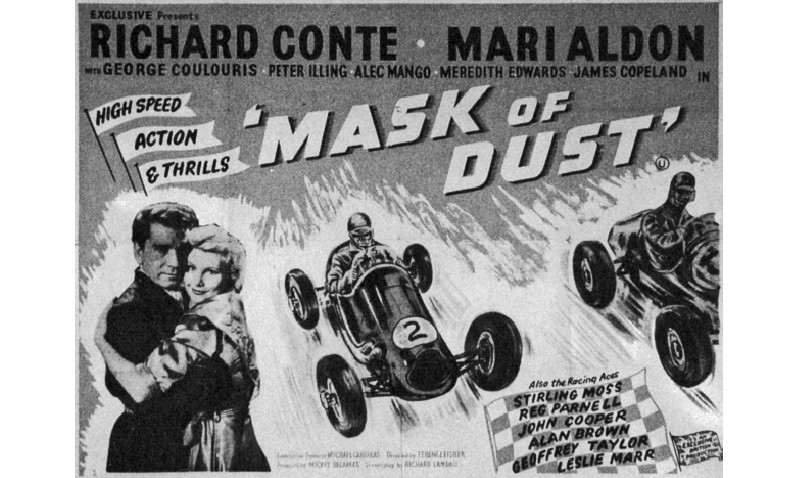

Released December 27, 1954 (U.K.), January, 1955 (U.S.); 79 minutes (U.K.), 69 minutes (U.S.); B & W; 7114 feeet; a Hammer Film Production; Released by Exclusive (U.K.), Lippert (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios and at various racetracks; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Mickey Delmar; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Richard Landau, based on Jon Manchip White’s novel; Director of Photography: James Harvey; Music: Leonard Salzedo; Art Director: J. Elder Wills; Editor: Bill Lenny; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Sound Mixer: Sid Wiles; Sound Camera Operator: Don Alton; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Wardrobe: Molly Arbuthnott; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Hairstyles: Monica Hustler; Production Manager: Jimmy Sangster; U.S. Title: A Race for Life; U.K. Certificate: U.

Poster from Mask of Dust (courtesy of Fred Humphries and Colin Cowie).

Richard Conte (Peter Wells), Mari Aldon (Pat Wells), George Coulouris (Dallapiccola), Peter Illing (Bellario), Alex Mango (Rizett), Meredith Edwards (Lawrence), James Copeland (Johnny), Jeremy Hawk, Richard Marner, Edwin Richfield, Tom Turner, Stirling Moss, Reg Parnell, John Cooper, Geoffrey Taylor, Leslie Marr (drivers).

Since leaving the Air Force, race driver Peter Wells (Richard Conte) has been attempting to recapture his former glory. He is now the number three driver on the Italian Corsi team, and both the manager Bellario (Peter Illing) and Peter’s wife Pat (Mari Aldon) want him to give it up. When fellow driver Dallapiccola (George Coulouris) tries to persuade him to quit, Wells argues with his old friend. During the race, Wells learns during a pit stop that Dallapiccola has had a serious crash. He pulls out of the race—despite Bellario’s warning—to see his dying friend. As a result, Wells loses his place on the team—and Pat—who leaves him when he still refuses to retire. Bellario gives him a last chance in the Italian Grand Prix by giving him an old car in poor condition. During the race, the car leaks oil, blinding Wells and making him a potential living torch. Despite Bellario’s demands, Wells refuses to quit and, motivated further by Pat’s presence, wins in a photo finish. After proving to everyone—and himself—that he’s still a champion, Wells retires.

No matter who stars, a car racing picture is basically a bunch of cars going around in a circle with off-track cliches added to pad the length. From James Cagney’s The Crowd Roars (1932) to Clark Gable’s To Please a Lady (1950) to Steve McQueen’s LeMans (1971), the story was pretty much the same. Hammer’s attempt at the genre was, according to the Kinematograph Weekly (May 13, 1954), “The first British production written around the lives of racing drivers.” Filming began on March 25, 1954, with first-time producer Mickey Delmar. Terence Fisher had become Hammer’s “house director,” guiding eleven of the twenty films made since he joined the company. He was considered something of a pioneer by the cinema press after directing Spaceways, the first post-war British science fiction film, and, next, this racing film. Fisher took a camera unit and Richard Conte to Goodwood Track to shoot actual racing scenes during the Easter meeting. Present were top drivers Stirling Moss and John Cooper. Four stationary cameras were used to catch both the cars and the crowd reactions, plus a camera car on the track.

Richard Conte’s participation caused a minor uproar in the press. “Why put a Hollywood actor in the hero’s driving seat in a British film about racing cars?” whined The Daily Cinema (May 13, 1954). “The answer beats me. It was galling to see the camera film a closeup of Conte at the controls of a racing car and then to see British driver Geoffrey Taylor doubling for him.” Mask of Dust was one of the first films to use racing drivers themselves. In addition to Moss and Cooper, other top drivers included Jeremy Hawk, Richard Marner, Edward Rechfield, and Reg Parnell.

Filming ended on May 8, 1954, followed by a November 23 trade show and a December 27 release. Reviews were positive, if not ecstatic. The British Film Institute’s Monthly Bulletin (January, 1955): “Skillful use of newsreel footage in the actual racing sequences raise the routine story slightly higher than average”; Variety (February 7): “An OK entry for minor double billing.”

Mask of Dust ended Hammer’s brief fling with sports begun with The Flanagan Boy, and the company would return to mostly routine thrillers before hitting its stride with the Quatermass Xperiment.

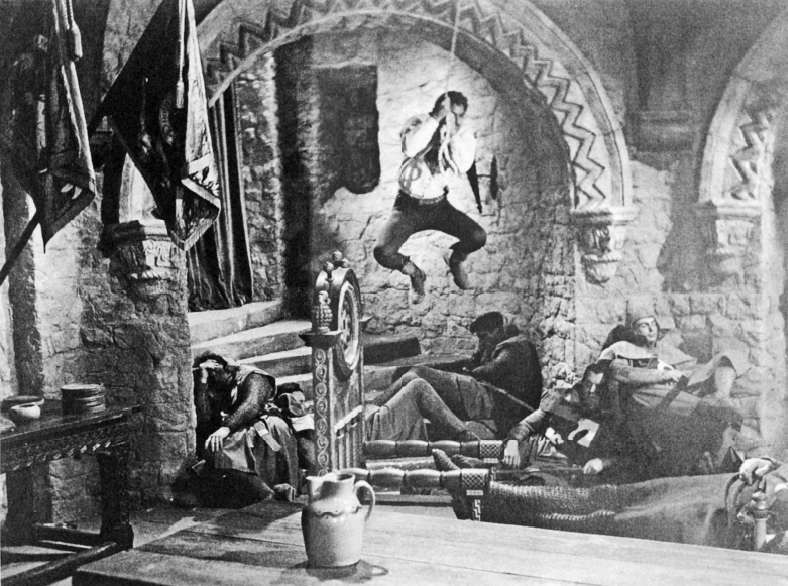

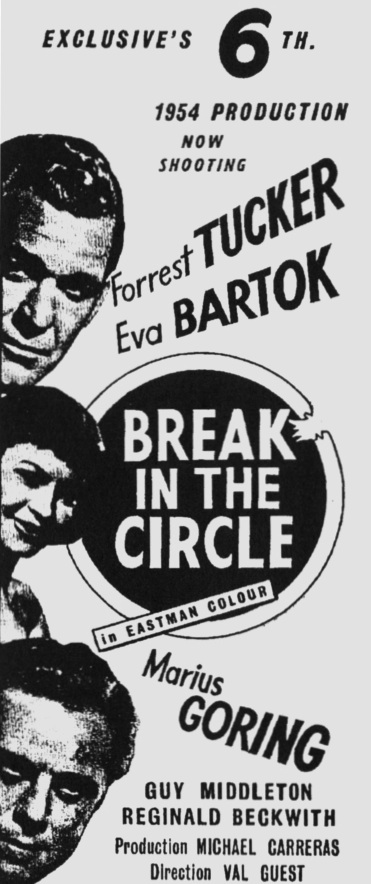

Released December 6, 1954 (U.K.); 77 minutes; Eastman Color; 6970 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Release (U.K.); an Astor Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Val Guest; Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Allan Mackinnon; Director of Photography: Jimmy Harvey; Music composed by: Doreen Corwithen; Art Director: J. Elder Wills; Production Manager: Jimmy Sangster; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Wardrobe Mistress: Molly Arbuthnot; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Sound Mixer: David Wiles; Sound Camera Operator: Don Alton; Editor: James Needs; Hair Stylist: Mary Hostler; U.K. Certificate: U.

Don Taylor (Robin Hood), Reginald Beckwith (Friar Tuck), Eileen Moore (Lady Alys), David King Wood (Sir Guy Belton), Douglas Wilmer (Sir Nigel Saltire), Harold Lang (Hubert), Ballard Berkeley (Walter), Wensley Pithy (Hugo), Leslie Linder (Little John), John Van Eyssen (Will Scarlet), Toke Townsley (Father David), Vera Pearce (Elvira), John Stuart (Moran), John Kerr (Brian of Eskdale), Raymond Rollett (Abbott); Leonard Sachs (Sheriff of Nottingham), Howard Lang (Town Crier), Jackie Lane (Mary), Tom Bowan, Bernard Bresslaw, Michael Godfrey, Dennis Wyndham, Jack McNaughton (Merry Men), and Patrick Holt (King Richard).

England, 1194. While fighting the Crusades, King Richard (Patrick Holt) is taken prisoner and his throne seized by his scheming brother, John, who is opposed only by Robin Hood (Don Taylor) and his Merry Men. When John Fitzroy is found murdered in Sherwood Forest, Robin is unjustly accused. Fitzroy was killed because he carried plans to free Richard, which did not sit well with Sir Nigel (Douglas Wilmer) and the Count of Moraine (John Stuart). Robin traces the stolen plans to Sir Guy Belton (David King Wood) and, disguised as a troubadour, enters the castle and is warmly received by the beautiful lady Alys (Eileen Moore). Sir Nigel, an agent of Prince John’s, unmasks Robin and Friar Tuck (Reginald Beckwith) as spies, but they are freed by Alys. They foil the attempt to murder Richard, defeat Sir Guy’s rebels, and feast with the King and Alys on stolen Royal deer in Sherwood.

Men of Sherwood Forest was Hammer’s first color feature and the company’s first of three stabs at the ancient legend. Like other Robin Hood pictures, it pales in comparison to the 1938 Errol Flynn classic The Adventures of Robin Hood, but can stand on its own as an enjoyable little film. Val Guest (May, 1992) told the authors,

Robin Hood (Don Taylor) swings into action in Hammer’s first color feature, Men of Sherwood Forest.

I became involved with Robin Hood because of the success of Life with the Lyons. It was such a success that Hammer simply asked me to do another! They told me that Men of Sherwood Forest was going to be a send-up, and I thought it would be fun—and it was! I’d already done quite a few films—many of them comedies. This one wasn’t much of a departure from what Hammer knew I could do. I was never under contract to Hammer at any time. They used to call me every now and then and ask if I was free. I always had such fun making movies for them—a wonderful company to be with—I always said yes!

Starring as Robin was Don Taylor, who made his mark as an actor in The Naked City (1948) and later scored as a director with Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971). He recalled for the authors (May, 1992),

I’m not really sure how I got involved with Hammer, to tell you the truth. I had just broken up with my wife [Phyllis Avery], and I wanted to get away, get out of the country for a while, so I went to England. The next thing I knew … I guess with the beard and wig, I looked a bit like Errol Flynn. I had a mid-Atlantic accent so, by cheating a bit on my “a,” I could blend in with the British cast. By playing with an all-British cast—a typically solid, theatrically trained cast—I never even thought of the film being released in the USA. As you know, Hammer was a very small company—shot their films out of an old house on the Thames. We ate in the same building we filmed in! We were a real family for a few weeks; and when you get that camaraderie on film, you’ve really got something! I remember one scene where I was on horseback, leading my Merry Men on a charge. They were all stunt men—I was the only actor who could ride! I came up fast on a fence and hoped my horse was a jumper. We didn’t have time to scout the area first, and the fence was a real surprise! Val Guest was an excellent director—he knew what he wanted, and he got it. Every shot was outlined—except the one with the fence! I’d never worked with such a meticulous director before. I really liked working with him—especially socializing during the rushes. A very enjoyable time. I also enjoyed the Carreras family. Sir James—now there was a real businessman. He could sell a film before he even made it! I met him socially a few times, and he was a lot of fun—he set the tone for the whole company.

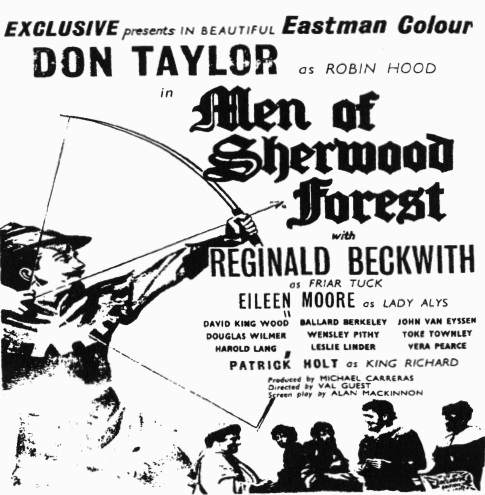

Trade advertisement.

Men of Sherwood Forest began production in May, 1954, with location filming at Clivedon. Several actors were hospitalized for broken bones and bruises. So many swords were broken that more had to be ordered. The Eastman Color process was going well, and Michael Carreras (The Kinematograph Weekly, June 10, 1954) was so pleased that he planned to use it for the next scheduled production, Break in the Circle, and for a Cromwell era picture (which eventually was filmed as The Scarlet Blade). Hammer’s production schedule was to finish for the year on November 1, and they were planning to rent Bray to other companies.

Men of Sherwood Forest was trade shown on October 27, 1954, at Studio One and was released on December 6. Most reviewers were impressed, including The Kinematograph Weekly (November 4): “Enthusiastic team, clean fun and fights, jolly to say the least”; and the British Film Institute’s Monthly Bulletin (December): “Don Taylor makes a good-natured Robin, and the tone of the film generally is genial.” The film is, within its limits, very enjoyable and not to be taken seriously. Hammer would return to contemporary subjects for its next nine features; the next “period” film would be The Curse of Frankenstein.

Released February 11, 1955 (U.K.); 81 minutes; B & W; 7618 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Films Release (U.K.); filmed in Southall, London, Osterley, and on location in Paris, France; Director, Screenplay: Val Guest; Producer: Robert Dunbar; based on the characters from the BBC Radio Series; Director of Photography: James Harvey; Editor: Doug Myers; Music: Bruce Campbell; Art Director: Wilfred Arnold; Production Manager: Freddie Pearson; First Assistant Director: Rene Dupont; Second Assistant Director: Roger Good; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Wardrobe: Molly Arbuthnot; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Hair Stylist: Nina Broe; Sound Mixer: C.T. Mason; Sound Camera: John Soutar. U.S. Title: The Lyons Abroad; U.K. Certificate: U.

Ben Lyon, Bebe Daniels, Barbara Lyon, Richard Lyon (Themselves), Horace Percival (Mr. Wimple), Molly Weir (Aggie), Doris Rogers (Florrie), Gwen Lewis (Mrs. Wimple), Hugh Morton (Colonel Price), Reginald Beckwith (Captain Le Grand), Martine Alexis (Fifi La Pleur), Pierre Dudan (Charles), Dino Galvani (Gerrard).

The Lyon family has settled into their new home, but the usual disasters continue. Bebe (Bebe Daniels) has forgotten that she hired decorators and is afraid that Ben (Ben Lyon) has forgotten their anniversary. His perceived neglect comes to a head when their son, Richard (Richard Lyon), discovers that Ben has made a dinner date with review star Fifi La Pleur (Martine Alexis). All is forgiven when Ben reveals that he arranged to buy her Channel tickets so he could take the family to Paris to celebrate. After arriving in Paris, Ben runs into Fifi again, but their innocent meeting is misinterpreted by her jealous husband, Captain Le Grand (Reginald Beckwith). He is a champion duellist, and challenges Ben to meet him at dawn. With Fifi’s help, Ben solves the predicament, and all is well for the Lyon family once again.

Hammer’s diversity is well illustrated in this trade ad.

Hammer’s faith in the Lyon family’s popularity was so great that the company began production on this sequel while Life with the Lyons was still in release. As a cost-saving measure, Hammer arranged to film interiors for The Lyons in Paris at Southall Studios where the Lyons television series was produced. After completing Men of Sherwood Forest, Val Guest took a five-day break and was off to Paris to scout locations, and filming began on June 28, 1954. As he had done on the first film, Guest compressed three Lyons radio series episodes into one screenplay. The scheduled four week shoot ended on July 26, and included location work in Osterley, as well as Paris. The Lyons in Paris went into general release on February 11, 1955. Unlike its predecessor, the picture had been given a prestigious West End premiere at the Plaza on February 4. The Lyons were big business and were now treated accordingly, receiving mostly positive reviews. The Star (February 11): “Homey, knockout fun put over with tremendous gusto”; The Monthly Film Bulletin (February): “There are some amusing moments in this naive and cheerful romp”; and The Daily Sketch (February 11): “Guaranteed to pay off handsomely in laughs.”

After two successful Lyon Family pictures, all concerned wisely decided to end the brief series. Once again, Val Guest delivered a well-made, successful picture and had become Hammer’s top director.

Released August 29, 1955 (U.K.); 59 minutes; B & W; 5324 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Release (U.K.), a Lippert Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Montgomery Tully; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Screenplay: Richard Landau, based on A.E. Martin’s novel; Director of Photography: Walter Harvey; Music composed by: Leonard Salzedo; Musical Director: John Hollingsworth; Art Director; J. Elder Wills; Production Manager: T.S. Lyndon-Haynes; Editor: James Needs; Assembly Cutter: Henry Richardson; Camera Operator: Noel Rowland; Sound Recordist: H.C. Pearson; Makeup: H.F. Richmond; Hairdresser: Jean Bear; U.S. Title: The Glass Tomb; U.K. Certificate: A.

John Ireland (Pel), Honor Blackman (Jenny), Geoffrey Keen (Stanton), Eric Pohlmann (Sapolio), Sidney James (Lewis), Liam Redmond (Lindley), Sidney Tatler (Rorke), Valerie Vernon (Bella), Arnold Marle (Pop), Nora Gordon (Marie), Sam Kydd (Georgy), Ferdy Mayne (Bertie), Tonia Bern (Rena), Arthur Howard (Rutland), Stan Little (Mickelwitz), Anthony Richmond (Peter).

“Pel” Pelham (John Ireland), a devoted family man, is involved with the low end of British show business, booking sensational acts for sleazy carnivals. His latest scheme is Sapolio (Eric Pohlmann), the Fasting Man. Tony Lewis (Sidney James), Pel’s friend and notorious bookmaker, is being blackmailed by Rena (Tonia Bern), an old flame, on the eve of his wedding. While a party for the carnival performers is being held at Sapolio’s apartment, Rena is murdered upstairs by Harry Stanton (Geoffrey Keen), who forced her to torment Tony. He is glimpsed by Sapolio.

Enclosed in a glass cage, Sapolio begins his fast as Peel, fearing that Tony killed Rena, makes inquiries. His wife, Jenny (Honor Blackman), is kidnapped, and his son, Peter (Anthony Richmond) is threatened. When Pel calls the police, he’s told Tony has been murdered. Pel’s next shock is Sapolio’s murder by poison. The public is told, however, that he’s in a coma. Stanton, disguised as a nurse, enters the cage to finish the job and is shot by the police. Rena had threatened to expose his illegal activities, so he killed her, his blackmail victim, and the unfortunate Sapolio, who saw him in the shadows.

The Glass Cage is an absurd, poorly made film that must be seen to be believed. To start with, what could possibly be less interesting than watching a man not eat? Making this even more difficult to “swallow” is that Eric Pohlmann, the “starving man,” is fifty pounds overweight! With such a ludicrous premise, even the film’s few good points are easily overlooked. For example, young Peter has developed an eating disorder due to his fear of starvation. Although the movie never had much in its favor, it was made worse by extensive cutting. The editing is disjointed, and the running time is less than an hour.

Filming began on July 19, 1954, and it was trade shown a year later, indicating that something had gone wrong. Reviewers, following an August 29 release, didn’t know what to make of it. Today’s Cinema (July 15, 1955): “Overcomplicated plot, direction concise to the point of jerkiness”; the British Film Institute’s Monthly Bulletin (September, 1955): “Naively handled.”

For a film dealing with freaks and sleazy carnivals, there were just too many missed opportunities. Originally titled The Outsiders, it should have concentrated more on fringe performers that populated this odd world than on the pointless blackmail/murder plot. The Glass Cage was Hammer’s second to last film before its rebirth via The Quatermass Xperiment, which didn’t come a second too soon.

Released February 28, 1955 (U.K.); May, 1957 (U.S.); 91 minutes (U.K.), 69 minutes (U.S.); Eastman Color (U.K.); B & W (U.S.); 8274 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Release (U.K.); a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Val Guest; Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Val Guest, from Philip Lorraine’s novel; Director of Photography: Walter Harvey; Music composed by: Doreen Carwithen; Musical Director: John Hollingsworth; Production Design: J. Elder Wills; Production Manager; Jimmy Sangster; Associate Producer: Mickey Delmar; Editor: Bill Lenny; Sound Recordist: H.C. Pearson, Ken Cameron; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Hairdresser: Monica Hustler; Wardrobe: Molly Arbuthnot; Continuity: Connie Willis; Dubbing Editor: Dino del Campo; U.K. Certificate: U.

Forrest Tucker (Morgan), Eva Bartok (Lisa), Marius Goring (Baron Keller), Reginald Beckwith (Dusty), Eric Pohlmann (Emile), Guy Middleton (Hobart), Arnold Marle (Kudnic), Fred Johnson (Farguarson), David King-Wood (Patchway), Guido Lorraine (Franz), Andre Mikhelson (first Russian), Stanley Zevic (second Russian), Marne Maitland (third Russian), Derek Prentice (Butler).

An early cold war thriller.

Adventurer Skip Morgan (Forrest Tucker) and his friend Dusty (Reginald Beckwith) earn a living delivering contraband in the Bonaventure, a high-powered cabin cruiser. They are hired by Baron Keller (Marius Goring), an international financier, to smuggle Kudnic (Arnold Marle), a scientist, out of Germany. Before leaving, Morgan discovers that Lisa (Eva Bartok), his neighbor, is actually an operative of British Intelligence. He assumes that she is spying on him and forces her aboard the Bonaventure. When they arrive in Hamburg, Morgan learns that Kudnic has been abducted. He recklessly intervenes, frees Kudnic, and takes him to England.

There, Morgan learns why he was hired—Keller wants a fuel formula Kudnic has developed that is worth millions. Morgan then raises his price to complete the deal. After being released, Lisa contacts her superiors, and the Coast Guard is present when the exchange takes place. Keller is carrying a gun, not Morgan’s expected loot, and forces him to put to sea. Morgan overpowers Keller and throws him overboard to his death before surrendering to the police—and exchanging a knowing look with Lisa.

Break in the Circle was Hammer’s second color film (following Men of Sherwood Forest). Both were directed by Val Guest, who recalled for the authors (May, 1992) Hammer’s hiring policy during the mid-fifties. “Hammer had a list of actors that the American distributors would accept, and Forrest Tucker was on that list. When he came along for the lead in Break in the Circle, I was quite pleased—I got along very well with Tuck. No, I didn’t request him later for The Abominable Snowman. He was just on the list.”

With a plot centering on the cold war, Break in the Circle anticipated the spy dramas of the sixties, but was based in a reality far removed from Ian Fleming’s James Bond. James Carreras had high hopes for the film, which The Kinematograph Weekly (August 19, 1954) branded as “Hammer’s biggest production.” Carreras had just completed his sixth film of the year and scheduled a generous six-week schedule, location work in Germany and Cornwall, plus Eastman color for Break in the Circle. Filming began on August 22 on location, with only two weeks spent at Bray. During the Cornwall shoot, Marius Goring nearly drowned while doing his fall from the Bonaventure. He was waiting for Guest to end the scene, but was too far away to hear the director shout “Cut!” The dedicated actor kept thrashing and refused to be pulled back on board.

Break in the Circle was completed on schedule, was trade shown on February 10, 1955, at Studio One, and premiered on the 28th to indifferent reviews. The British Film Institute’s Monthly Bulletin (April): “Schoolboy adventure yarn, a rousing romp for the unsophisticated”; The Kinematograph Weekly (February 17): “Intriguing and exciting”; and Variety (May 8, 1957): “A weak entry for the American market.” Despite looking good on paper, the film doesn’t have much to offer. After an exciting, out of context opening of Kudnic escaping through an ominous forest, the picture quickly settles for the conventional, and may be Guest’s least interesting effort for Hammer.

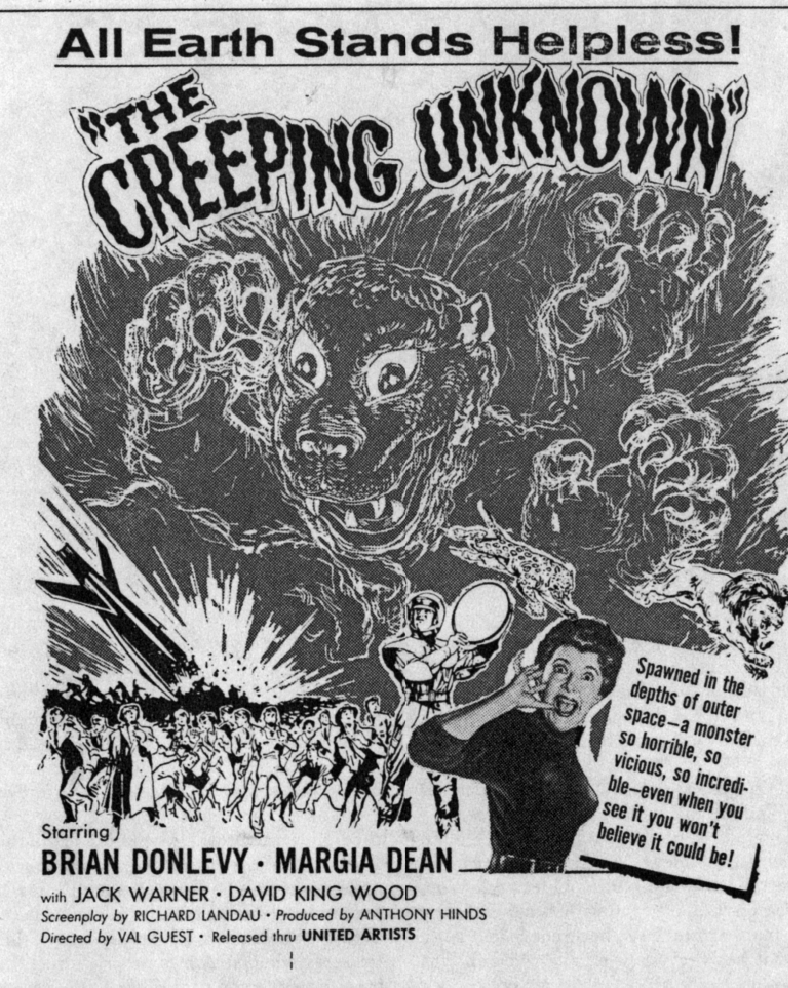

Released September 28, 1955 (U.K.); 82 minutes (U.K.), 78 minutes (U.S.); B & W; 7380 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Exclusive Release (U.K.), a United Artists Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Val Guest; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Screenplay: Val Guest, Richard Landau, based on Nigel Kneale’s BBC production; Director of Photography: Walter Harvey; Music composed by James Bernard; Music Supervisor: John Hollingsworth; Art Director: J. Elder Wills; Production Manager: T.S. Lyndon-Hayes; Editor: James Needs; Special Effects: Les Bowie; Sound Recordist: H.C. Pearson; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Hairstyles: Monica Hustler; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Assistant Director: Bill Shore; U.S. Title: The Creeping Unknown; U.K. Certificate: X.

Brian Donlevy (Quatermass), Jack Warner (Lomax), Margia Dean (Judith), Richard Wordsworth (Caroon), David King Wood (Briscoe), Thora Hird (Rosie), Gordon Jackson (Producer), Harold Lang (Christie), Lionel Jeffries (Blake), Maurice Kauffman (Marsh), Gron Davies (Green), Stanley Van Beers (Reichenheim), Frank Phillips (BBC Announcer), Arthur Lovegrove (Sgt. Bromley), John Stirling (Major), Eric Corrie (Young Man), Margaret Anderson (Maggie), Henry Longhurst (Maggie’s Father), Michael Godfrey (Fireman), Fred Johnson (Inspector), George Roderick (Policeman), Ernest Hare (Fire Chief), John Kerr (Lab Assistant), John Wynn (Best), Toke Townley (Chemist), Bartlett Mullins (Zoo Keeper), Molly Glessing (Mother at Zoo), Mayne Lynton (Zoo Official), Harry Brunsing (Night Porter), Barry Lowe (Tucker), Jane Aird (Mrs. Lomax), Sam Kydd (Station Sergeant), Arthur Gross (Floor Boy), James Drake (Sound Engineer), Edward Dane (Policeman), Basil Dignam (Sir Lionel), Betty Impry (Nurse), Marianne Stone (Nurse).

Professor Quatermass (Brian Donlevy) arrives at the scene of the crash of a rocket containing three scientists—Green (Gron Davies), Reichenheim (Stanley Van Beers), and Victor Caroon (Richard Wordsworth). Caroon stumbles out alone, with no trace of his companions, and Blake (Lionel Jeffries) demands a full investigation. Judith Caroon (Margia Dean) allows her husband to be placed under Quatermass’ supervision—Victor is in an odd, zombie-like state, and his physical structure is changing. By studying film taken inside the rocket, Quatermass determines that a “disturbance” took place in space—and that the men’s bodies were invaded by something alien. Judith hires Christie (Harold Lang), a private investigator, to get Victor away from Quatermass’ probing, but Caroon is no longer human. It kills Christie in an elevator, its hand mutated into a cactus plant it absorbed. Judith notices “Victor’s” distorted face and hand and screams.

“Victor” encounters a child at play and moves to absorb her life force, but some human remnant inside him frightens her off. Now an unrecognizable thing, it enters a zoo and absorbs the life out of several animals. The tentacled monster hides in Westminster Abbey and is discovered by a film crew. Quatermass diverts London’s electrical power into the creature and destroys it, planning to start again in his space exploration.

“It was quite different from anything I’d previously done,” Val Guest told the authors (May, 1992). “I was very loath to do it. I didn’t think it was my cup of tea at all.” Despite his misgivings, The Quatermass Xperiment was one of Hammer’s most important films and is among the best science fiction movies. Nigel Kneale’s original story, a six-part serial broadcast on the BBC in July, 1953, ran two hundred minutes. It was incredibly popular, and Hammer was fortunate to get the film rights. A main problem was cutting over three hours of story in half to attain feature film length. Accordingly, Kneale was not pleased. “I was disappointed in the film,” he said (Starlog, February, 1989), “because I had very little to do with it.” Val Guest was, in turn, unhappy about Kneale’s reaction. “I really, honestly, am sad about the situation with Nigel,” he told author Tom Weaver. “He’s a brilliant guy, and he’s had an enormous success with all these things—and he hates every minute of them!”

The Quatermass Xperiment—a science fiction classic—bore the U.S. title The Creeping Unknown.

A little seen Phil Leakey makeup effect for The Quatermass Xperiment.

A second “controversy” has centered around Brian Donlevy’s performance. Although he’s no one’s idea of a brilliant scientist, Donlevy does bring authority to the role if nothing else. Guest told Tom Weaver, “Oh, I got on with Brian fine. But so many stories have been concocted since about how he was a paralytic drunk. It’s absolute balls. He wasn’t stone cold sober, either, but he was a pro and knew his lines.” In their desire for a “name” actor—preferably an American—in the lead, Hammer was guilty of miscasting. They did much better with Andrew Keir in Quatermass and the Pit.

Filming began on October 18, 1954, at Bray after location work at the London Zoo on the 14th. Further location work was done in the village of Bray and near Windsor Castle. Following an August 25, 1955, trade show at Studio One, The Quatermass Xperiment (the “E” was dropped to emphasize the X certificate) premiered on September 28 at the Pavilion. Paired with Rififi , the package was chosen as the best double feature of 1955. In general release on the ABC circuit, the film went out with Hammer’s featurette The Eric Winston Show Band and broke several house records. Reviews were generally favorable. The London Times (August 29, 1955): “The director certainly knows his business when it comes to providing the more horrid brand of thrills”; The Chronicle (August 26): “This is the best and nastiest horror film that I have seen since the war”; The Manchester Guardian (August 27): “A lively piece of science fiction”; The Star: “There can be no higher praise for a science fiction film”; The New Statesman (August 27): “What a surprise!”; the British Film Institute’s Monthly Bulletin (October): “Richard Wordsworth’s tortured grimace and menacing makeup suggest a pathetic as well as horrible figure”; Variety (September 7): “Despite its obvious horror angles, production is crammed with incident and suspense”; and Harrison Reports (June 23, 1956): “Adult fare.”

Despite this being Val Guest’s first science fiction movie, he knew exactly what he wanted. “I said I would do it, provided that I could shoot it as if some newsreel company had said, ‘Go out and cover this story,’” he told the authors. “It was the first time I used a ‘cinema verité technique.’ I found that a fun way to do it.” When asked if he would have liked the opportunity to direct The Curse of Frankenstein, Guest replied, “Despite the success of the horror elements in Quatermass, I wouldn’t have been a good choice. Gothic horror has never been anything I’ve gone for. I don’t recall if Hammer ever discussed it with me, but I wouldn’t have taken it even if they had!”

Like all good movies, The Quatermass Xperiment was a collaborative effort. Guest’s Val Lewton–like avoidance of blatant shock in favor of mood was augmented by Richard Wordsworth’s stunning acting—a Karloff level performance. Phil Leakey created his first horror makeup perfectly, and James Bernard’s shrieking violins added to the tension. “This was my first film score,” he told the authors (July, 1994). “I thought the subject was quite stark and spare, and wrote the music accordingly. I just hoped I was right!”

The film was released in America as The Creeping Unknown, since the Quatermass name meant nothing. Supposedly, a young boy died of fright during a performance in Rockport, Illinois. That’s not hard to believe—this is frightening science fiction at its best.