Released June, 1958 (U.S.), November 17, 1958 (U.K.); 91 minutes; Technicolor; 7982 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a Columbia Release; filmed at Bray Studios, England; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Associate Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Jimmy Sangster; Additional Dialogue: Hurford Janes; Music: Leonard Salzedo; Conductor: Muir Mathieson; Musical Supervisor: John Hollingsworth; Director of Photography: Jack Asher; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Alfred Cox; Sound Recordist: Jock May; Production Manager: Don Weeks; Camera: Len Harris; Makeup: Phil Leakey, Hal Liesley; Hairstyles: Henry Montsash; Continuity: Doreen Dearnaley; Wardrobe: Rosemary Burrows; Chief Set Electrician: Robert Petzoldt; Assistant Director: Robert Lynn; Clapper/Loader: Tony Powell; 2nd Assistant Director: Tom Walls; Focus: Harry Oakes; Camera Grip: Albert Cowland; Working Title: Blood of Frankenstein; U.K. Certificate: X.

Peter Cushing (Dr. Victor Stein/Frankenstein), Francis Matthews (Dr. Hans Kleve), Eunice Gayson (Margaret), Michael Gwynn (“Karl”), John Welsh (Bergman), Lionel Jeffries (Fritz), Oscar Quitak (Karl), Richard Wordsworth (Up Patient), Charles Lloyd Pack (President), John Stuart (Inspector), Arnold Diamond (Molke), Margery Cresley (Countess Barscynska), Anna Walmsley (Vera Barscynska), George Woodbridge (Janitor), Michael Ripper (Kurt), Ian Whittaker (Boy), Avril Leslie (Girl), Michael Mulcaster (Tattoo).

Baron Frankenstein (Peter Cushing)—condemned to the guillotine to pay for his crimes—is rescued by Karl (Oscar Quitak), a crippled guard, in exchange for a new, perfect body. With a priest buried in his place, the Baron—now calling himself “Dr. Stein,” establishes a thriving practice in Carlsbruck, which perturbs the city’s Medical Council. One of the doctors, Hans Kleve (Francis Matthews) recognizes the Baron, but is willing to keep the secret in exchange for knowledge. The pair transplant Karl’s brain into a perfect body created from the amputated limbs of Dr. Stein’s charity patients. The “new” Karl (Michael Gwynn) realizes he must take care—a similar operation on an orangutan resulted in its becoming a cannibal. He is even more determined after meeting Margaret (Eunice Gayson), a volunteer at the clinic, and he revels in the thought of becoming a normal man.

After Hans foolishly tells Karl that Dr. Stein plans to put him on display, he is repelled at still being an object of curiosity, and escapes. Returning to the lab where he was “born,” Karl destroys his old body, but is beaten by the janitor (George Woodbridge). Maddened, Karl strangles his attacker and is overcome by a hideous desire. His body twisting into its former shape, Karl hides in a park where he brutally attacks a young woman (Avril Leslie). Drawn to Margaret, he staggers into a party attended by Dr. Stein and Hans. He calls for Frankenstein’s help, and dies at his creator’s feet. When Stein’s patients learn of his true activities, they attack him. Hans takes the dying Baron to the lab and, following previous instructions, transplants his mentor’s brain into a previously prepared body.

At his posh London office, “Dr. Franck,” his forehead scarred, greets his new patients as Hans looks on approvingly.

Hammer had accurately predicted the box office potential of The Curse of Frankenstein and, in March, 1957—two months before the picture was released—registered a title (The Blood of Frankenstein) for its sequel. When asked by The Sunday Express how he planned to revive the Baron, James Carreras commented, “Oh, we sew his head back on again!” He and Michael flew to New York in late October to finalize with Columbia the production of the pilot for the TV series, Tales of Frankenstein.

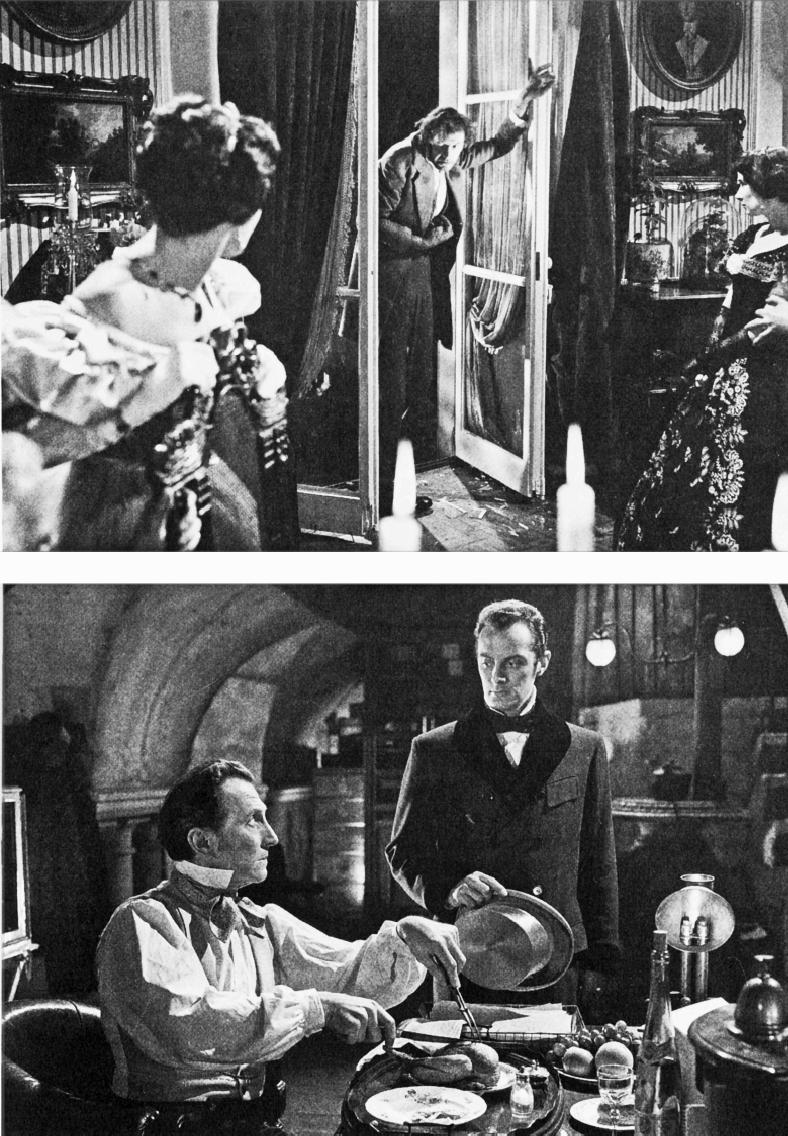

Top: Karl (Michael Gwynn) crashes Margaret’s (Eunice Gayson) party looking for Dr. Stein in The Revenge of Frankenstein. Bottom: Dr. Stein’s (Peter Cushing) notorious past is about to catch up with him in the form of Francis Matthews.

Production of the retitled The Revenge of Frankenstein began on January 6, 1958. Anthony Hinds (The Daily Cinema, January 2) assured fans that the picture “would contain all the shake, shudder, and wallop” of the original. To lower production costs, Hinds utilized several revamped sets from Dracula. This practice would soon bring complaints from some critics, but enabled Hammer to give its films a rich look at a discount.

A rare case of the sequel surpassing the original.

When The Kinematograph Weekly (January 20, 1958) visited Terence Fisher on the set, he said, “It’s no good having your tongue in your cheek when you are making horror films. You must be completely sincere. It is very difficult trying to stop people laughing in the wrong places. But there are also wonderful opportunities to put in intentional laughs.” It was apparent that Hammer tried to make up for Curse’s grim premise by supplying some humor courtesy of writer George Baxt. He told the authors (June, 1992), “I ‘ghosted’ two scenes for The Revenge of Frankenstein. One was with the two grave robbers, and the other was an amputation followed by Cushing ‘amputating’ a roast chicken.” When asked if he was the Hurford Janes who shared screen credit with Jimmy Sangster, Baxt merely laughed.

Sangster’s screenplay is one of his best, and took the Hammer series in a completely different direction from its predecessor. While Curse at least paid lip service to the novel and earlier films, Revenge was pure Hammer. “I just thought about what frightened me the most,” Sangster told the authors (August, 1993). “And what frightens me will frighten you.” What separates this film from the “average” horror movie is the fascinating “monster,” excellently played by Michael Gwynn. Sangster created a truly sympathetic character, and Gwynn’s acting makes the viewer truly uncomfortable as he goes from the elation of being “normal” to the horror of realizing that it was all for nothing. “He was a classically trained actor,” Len Harris told the authors (August, 1994), “who preferred the stage and, although he was excellent in Revenge, he wasn’t interested in pursuing a film career. He only did films occasionally but was in great demand.” Harris also recalled the crowded conditions at Bray. “During the scene in which Peter Cushing was beaten, if you look closely as he is on the floor, you’ll see an old blanket next to him. The blanket was thrown down as the camera moved back to cover the tracks.” He also remembered a near disaster. “For some reason, the large tank that contained Michael Gwynn shattered when we were all at lunch. Thank God he wasn’t in it.”

Filming ended on March 4, 1958, and, two days later, the Tales of Frankenstein pilot starring Anton Diffring concluded in Hollywood. Michael Carreras hoped that the first of 26 further episodes would begin at Bray in June, but, as he recalled (Little Shoppe of Horrors 4), “Tony Hinds went to America to Screen Gems, and he ran into a lot of trouble. They didn’t understand the concept, and they wanted to Americanize it. They wanted to do a series nothing like our films.” As a result, the poorly made pilot was all that came of a good idea.

The Revenge of Frankenstein was released in the U.S. in June co-featured with the excellent Curse of the Demon, and was hailed by Variety (June 18) as a “high grade horror film, gory enough to give adults a squeamish second thought and a thoroughly unpleasant one.” The U.K. premiere was held at midnight at the Plaza on August 27. In attendance were Valerie Hobson (Elizabeth in Bride of Frankenstein) and her soon-to-be disgraced husband, John Profumo. (Profumo, a member of Parliament, admitted to sharing call girl Christine Keeler with a Soviet agent.) Joining them were Peter and Helen Cushing. When asked why he enjoyed making films for Hammer, Cushing replied, “Great skill goes into their making. They demand the very best an actor can give. And it is these films, more than any others, which have done so much to establish me with world audiences.” Unlike some, Cushing was always grateful to the company and never downplayed its role in his success. Reviewers were, not surprisingly, split. The Evening Standard (August 28): “The latest monster looks like a handsome frontrow forward recovering from a head injury”; The News Chronicle (August 29): “I relish shockers like [this]”; The Observer (August 31): “A vulgar, stupid, nasty, and intolerably tedious business”; The Spectator (September 5): “The lowest level to which we were obliged to crawl”; The Daily Cinema (August 27): “A handsome deluxe production”; and The Kinematograph Weekly (August 28): “Immaculately tailored, gripping and intriguing story, faultless atmosphere.” The picture went into general release on November 17, generating respectable, but far less, business than The Curse.

The Revenge of Frankenstein set the Hammer style that would captivate audiences for years to come. “At first, people regarded color as something reserved for musicals and comedies,” said photographer Jack Asher (The Kinematograph Weekly, January 30, 1958). “I think we proved with the first Frankenstein picture that color would heighten the dramatic effect.” Audiences perceived color as the mark of a “classy” horror film, and Hammer would have the field to itself until American International’s Poe series in 1960.

Released June 15, 1959 (U.K.), July, 1959 (U.S.); 93 minutes, (original running time: 131 minutes); B & W, 8448 feet; a Hammer–7 Arts Production; a United Artists Release; filmed on location in Berlin, Germany; Director, Screenplay: Robert Aldrich; Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Teddi Sherman, based on the novel The Phoenix by Lawrence P. Bachmann; Director of Photography: Ernest Laszlo; Editor: Henry Richardson; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Music: Richard Farrell, Kenneth V. Jones; Conductor: Muir Mathieson; Art Director: Ken Adam; Production Manager: Basil Keys; Technical Advisor: Gerhard Rabiger; Camera Operator: Len Harris; U.K. Certificate: A.

Jack Palance (Eric Koertner), Jeff Chandler (Karl Wirtz), Martine Carol (Margot Hofer), Robert Cornthwaite (Loeffler), Dave Willock (Tillig), Wes Addy (Sulke), Jimmy Goodwin (Globke), Virginia Baker (Friar Bauer), Richard Wattis (Major Haven), Nancy Lee (Ruth Sulke).

After the end of World War II, Karl Wirtz (Jeff Chandler) and Eric Koertner (Jack Palance) are released from a British POW camp and return to Berlin. Amid the ruins are thousands of unexploded bombs. Wirtz, Koertner, and their fellow POW join a demolition squad and form a unique pact. Each will contribute half of his pay to a fund which will be divided among the survivors. Wirtz and Koertner, never close, are driven farther apart by the job stress and their love for Margot Hofer (Martine Carol), a widow who runs their boarding house. One by one, the squad is decimated until only Wirtz and Koertner remain. When Wirtz finds a bomb with double fuses that requires special handling, he sees an opportunity to kill off his rival. His plan fails, and Wirtz is forced to try to dismantle the bomb alone and is killed in the attempt.

Hammer bought the rights to Lawrence P. Bachmann’s novel The Phoenix in 1955, and James Carreras planned to film it the next year with Stanley Baker and Gregory Peck. The picture remained on Hammer’s schedule through 1957, recast with Jack Palance and Peter Van Eyck. When Oscar nominee Jeff Chandler became available, Van Eyck was dropped. Michael Carreras and director Robert Aldrich flew to Berlin on January 7, 1958, to start preproduction. The film was a co-production with 7 Arts, and James Carreras enthused (The Daily Cinema, January 8), “We have been working on it for nearly two years. I think that when it comes to star power, the names of the three principal players carry a terrific box office wallop.” While Carreras and Aldrich were in Berlin, Jack Palance, who had acted for Aldrich in The Big Knife (1958) and Attack! (1956), arrived in London. After making an enemy of Columbia boss Harry Cohn, Aldrich became expendable in Hollywood and was available for European projects.

Filming began on February 24, 1958, at Berlin’s UFA Studios, but there was an immediate three day delay due to Aldrich’s becoming ill. A second, more intriguing delay was caused when Gerhard Rabiger—the film’s technical advisor—was called away to defuse a real 500 pound bomb. Len Harris recalled for the authors (August, 1994), “It was very sad going to the UFA Studio and seeing the graves of soldiers lining the road. You must remember that the war had only ended thirteen years previously and was still very real to us all. These soldiers died defending a film studio!” The West Berlin government cautioned Hammer not to demolish any sites during the production, because many walls were still strong enough to support new buildings. As a result, Hammer had to construct its own “ruins” to be demolished.

A different problem arose when Palance began to balk at the script when he considered it to be too philosophical and talky. “Palance’s was the pivotal part,” Aldrich recalled (The Films and Career of Robert Aldrich), “and when I lost control of him and he lost confidence in me, the resulting damage to the film was catastrophic.” Len Harris remembered Palance as

an odd man, but a very nice one. He was something of a ‘method’ actor—this was new to the old Hammer crew—and we weren’t quite sure what was going on. He was trying to live the part and couldn’t stand any interference while he was preparing himself. He’d walk around the studio, getting himself worked up, and believe me, you didn’t want to get in his way. He was definitely unapproachable during these times.

Problems on the set continued to mount when the German technicians objected to Aldrich’s directing technique. “Robert covered himself with hundreds of shots of the bomb,” said Harris. “One from this side, one from that side, one from this angle, closeup, whatever. The German crew called the picture Around the Bomb in Eighty Ways!”

Martine Carol and Jack Palance in Ten Seconds to Hell.

Ten Seconds to Hell, cut from 131 to 93 minutes by United Artists, was previewed at the Pavilion for three weeks starting in late April, 1959. Hammer’s lucky streak, recently praised by the trade press, was about to end. The Daily Mail (April 24): “Once you’ve seen one such bomb dispose of its disposer, you have seen the lot”; The London Times (April 27): “It is a pity that Mr. Palance acts as though he is on the verge of a fit”; The Kinematograph Weekly (April 30): “Uninspired acting, flabby direction, and pretentious dialogue”; and News of the World (April 26): “This first rate idea goes very much adrift.” The picture went into general release on June 15, and, by the middle of August, The Kinematograph Weekly (August 13) reported that Ten Seconds to Hell had “definitely gone down the drain.” The American response was no better, and the picture became a rare late fifties failure for Hammer. Despite looking (on paper at least) like a hit, none of the movie’s strong points seemed to meld properly, and what could have brought some “respectability” to Hammer brought nothing but disappointment.

Released October 20, 1958 (U.K.); 91 minutes; B & W; HammerScope; 8166 feet; a Hammer-Byron Production; a Columbia Release; filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Val Guest; Producer: Henry Halstead; Original Story and Screenplay by Val Guest, John Warren, and Len Heath; Director of Photography: Gerry Gibbs; Music: Stanley Black; Art Director: George Provis; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Production Supervisor: Fred Swann; Production Manager: Pat Marsden; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Hairdresser: Marjorie Whittie; Wardrobe: Molly Arbuthnot; Sound: Jock May; Continuity: Doreen Dearnaley; Technical Advisor: Commander Peter Peake; Editor: Bill Lenny; U.K. Certificate: U.

David Tomlinson (Fairweather), Frankie Howerd (Dibble), Shirley Eaton (Jane), Thora Hird (Mrs. Galloway), Lionel Jeffries (Barker), Lionel Murton (Perkins), Sam Kydd (Bates), John Warren (Cooky), David Lodge (Scouse), Harry Landis (Webster), Ian Whittaker (Lofty), Howard Williams (Bunts), Peter Collingwood (Chippy), Edwin Richfield (Bennett), Amy D’Alby (Edie), Esma Cannon (Maudie), Tom Gill (Phillippe), Jack LeWhite, Max Day (Kertoni Brothers), Mary Wilson (First Model), Katherine Byrne (Second Model), Eric Pohlmann (President), Stanley Unwin (Porter), Michael Goodliffe (Blackeney), Wolfe Morris (Algeroccan Major), John Singer (Dispatch Rider), Larry Nobel (Postman), Ballard Berkeley (Whacker), Judith Furse (Chief Wren), Michael Ripper (Ticket Collector), Joe Gibbon (Taxi Driver), Victor Brooke (Policeman), Cavan Malone (Signalman), Desmond Llewellyn (Yeoman), Basil Dignam (Flagship Commander), John Stuart (Admiral), Jess Conrad (Signalman), Patrick Holt (First Lt.), George Herbert (Officer), Charles Lloyd Pack (Ed Diablo), Walter Hudd (Consul), John Hall (Sea Scout).

The frigate Aristotle is sold to the Algeroccan government and its motley crew are horrified, as their illegal activities must end. As they ready the ship, the crew look to Bosun Dibble (Frankie Howerd) for “guidance.” He decides to advertise the trip as a one-way luxury voyage! Lieutenant Commander Fairweather (David Tomlinson) is, as usual, unaware of Dibble’s plans, and the Bosun manages to smuggle the equally unsuspecting vacationers on board. Once under sail, he explains them away as “diplomats.” A quick chat with Jane (Shirley Eaton) puts Fairweather wise, and he throws Dibble in the brig. But, he releases him when the Bosun convinces Fairweather that he invited the passengers aboard while drunk.

When they reach Algerroca, a revolution is under way, and they are not allowed to dock. Dibble raises an Algerrocan flag causing the rebels to flee, and Fairweather is proclaimed a hero by the president (Eric Pohlmann). As Fairweather is being decorated, the British consul (Walter Hudd) announces that the Algeroccan check has bounced. The sale is off, and the crew must leave their newly found fame for Britain to enjoy.

The success of Up the Creek called for a sequel, and Hammer, as usual, heard the call. Unfortunately, Peter Sellers, who carried the first film, was unavailable. “By the time we got to Further Up the Creek,” Val Guest told the authors (May, 1992), “Peter Sellers had grown too big. He was in Hollywood then—I had to take Frankie Howerd—absolutely brilliant—for the sequel.” Filming began on May 19, 1958, and Howerd was announced as Sellers’ replacement three days later. The picture was labeled a “Byron film for Exclusive release,” but it is a Hammer production and was referred to as such in the trade papers. The set for the Aristotle’s bridge was built over 40 feet high so that trees would not be accidentally photographed when the ship was “at sea.”

Val Guest was interviewed on the set (The Kinematograph Weekly, July 3) and commented on the danger of making a sequel. “You feel all the time that you have to do better than you did the first time, and at the back of it all is the feeling that, whatever you do, some of the critics will say it’s not as good.” Guest felt that Bray was an excellent place to film comedy. “Comedy needs pacing,” he said, “and professionals keep pace.” The production ended on July 11. “It’s an absolute riot,” said James Carreras (Daily Cinema, August 20) upon seeing the final cut. “It’s bigger and better than Up the Creek. It ought to be. It cost a lot of money.”

Further Up the Creek premiered at the Metropole Victoria on October 20, following an October 10 trade show at the Columbia. Guest’s fears were justified, as reviewers were less impressed with the sequel than with the original. The London Times (October 16): “One of those artless British films which have a Light Programme audience in mind”; The Monthly Bulletin (November): “A rather assorted mixture of established gags”; and The Kinematograph Weekly (October 16): “The film tickles the ribs without taxing the brain.” The most devastating review came six years later when James Carreras (The Sunday Times) proclaimed Further Up the Creek “a disaster.”

A trade ad for Further Up the Creek.

Hammer would continue its flirtation with service comedy with I Only Arsked and end it with Watch It Sailor!

I Only Arsked

Released November 8, 1959 (U.K.); 82 minutes; B & W; 7375 feet; a Hammer-Granada Production; a Columbia Release; filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Montgomery Tully; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Associate Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay: Sid Colin, Jack Davies, based on Granada TV’s The Army Game; Director of Photography: Lionel Banes; Production Manager: Don Weeks; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Makeup: Phil Leakey; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Alfred Cox; Music: Benjamin Franklin; Song “Alone Together” by Walter Ridley and Sid Colin; Assistant Director: John Peverall; Special Effects: Sid Pearson; 2nd Assistant Director: Tom Walis; Sound Mixer: Jock May; Sound Camera: Peter Day; Continuity: Doreen Dearnaley; Hair Styles: Henry Montsash; Art Director: John Stoll; U.K. Certificate: U.

A motley crew in Hammer’s service comedy, I Only Arsked.

Bernard Bresslaw (Popeye), Michael Medwin (Cpl. Springer), Alfie Bass (Boots), Geoffrey Sumner (Maj. Upshot-Bagley), Charles Hawtrey (Professor), Norman Rossington (Cupcake), David Lodge (Potty Chambers), Arthur Howard (Sir Redvers), Marne Maitland (King Fazim), Michael Bentine (Fred), Francis Matthews (Mahmoud), Michael Ripper (Azim), Wolfe Morris (Salesman), Ewen McDuff (Ferrers), Marie Devereux, Lizabeth Page, Claire Gordon, Barbara Pinney, Pamela Chamberlain, Jean Rainer, Clarissa Roberts, Gales Sheridan, Josephine Jay, Andrea Loren, Rebecca Wilson, Anna Griffiths, Pauline Chamberlain, Jennifer Mitchell, Julie Shearing, Maureen Moore, Anne Muller, Pamela Searle (Harem Girls).

To save Britain’s Middle East oil supply, Sir Redfers (Arthur Howard) requests that a “crack regiment” be sent to Darawa—where trouble is brewing. King Fazim (Marne Maitland) is about to lose his power to his shifty brother, Prince Mahmoud (Francis Matthews), and needs to strike oil—quickly. The British arrive—Popeye (Bernard Bresslaw), Major Upshot-Bagley (Geoffrey Sumner), Corporal Springer (Michael Medwin), the Professor (Charles Hawtrey), and Cupcake (Norman Rossington)—a real gang of losers. The Prince is overjoyed and plans their “removal,” as the boys—already homesick—send an unauthorized message to London, indicating that they are not needed. While waiting to be recalled, they find the tunnel leading to Fazim’s harem, and a reason to stay in Darawa.

The boys stage an oil strike so they can remain “on duty,” but the Prince uses the diversion to seize the throne. Popeye leads Sir Redfers, the King, and the girls through the tunnel, and traps the Prince by starting an avalanche. The grateful King offers his hospitality, but the “heroes” are recalled to London.

The Army Game was a successful Granada TV series, and was fair game for the Hammer treatment. After rounding up most of the cast, Hammer began production on July 21, 1958, on I Only Arsked—one of Popeye’s catchlines from the show. “So many people think that a box office success is merely a matter of getting a popular television team like this onto the screen,” said Anthony Hinds (The Kinematograph Weekly, August 21). “If it were that simple, every production company in the world would be doing it.” The problem, according to Hinds, was to convince people to pay for something they can see for free at home. As a result, Sid Colin’s script placed The Army Game boys in a completely new situation, far removed from the series. Director Montgomery Tully commented that, on TV, the actors could ad-lib, but “here we have had to stick more closely to the script.” A main selling point for Hammer was that the series team would not be returning intact the following season—Bernard Bresslaw was going AWOL. Highly popular on television, Bresslaw was poised to become a major film star, but never quite made it.

I Only Arsked finished production on August 22, 1958, was trade shown on November 1, and was hustled into a November 7 premiere at the Plaza. The Kinematograph Weekly (November 13) reported that the movie was “not breaking any records at the Plaza, but at least it’s holding its own.” The film gained momentum over Christmas and, outside London, outpaced The Camp on Blood Island, Hammer’s main money winner of 1958. Following this surge in popularity, I Only Arsked went into general release on the ABC circuit on February 9, 1959. James Carreras told The Daily Cinema (January 12), “It’s difficult to know what to make these days. You produce a horror film, and they eat it. Then you turn out a comedy, and they can’t run into the cinema fast enough.” By late February, I Only Arsked was doing the box office everyone felt possible, even in London where previously cool audiences were warming up.

Reviewers, however, were cautious in their praise: The Sunday Pictorial (November 9, 1958): “Funny but not witty”; The Evening News (November 11): “Cashes in on the popularity of farces that make British soldiers look foolish”; The New Statesman (November 23): “Infantile plot”; and The London Times (November 11): “Cheerful slapstick.”

At this point, Hammer could do no wrong, drawing huge crowds for films in several genres. The company would never produce as diversified a group of successful films again.

Released May 4, 1959 (U.K.), July, 1959 (U.S.); 84 minutes; Technicolor; 7772 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a United Artists Release; filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Associate Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay: Peter Bryan, based on the novel by Sir A. Conan Doyle; Music: James Bernard; Music Supervisor: John Hollingsworth; Director of Photography: Jack Asher; Editor: Alfred Cox; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Production Manager: Don Weeks; Sound Recordist: Jock May; Camera: Len Harris; Continuity: Shirley Barnes; Costumes: Molly Arbuthnot; Hairdresser: Henry Montsash; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Assistant Directors: John Peverall, Tom Walls; Special Effects: Syd Pearson; U.K. Certificate: A.

Peter Cushing (Sherlock Holmes), Andre Morell (Dr. Watson), Christopher Lee (Sir Henry Baskerville), Marla Landi (Cecile), David Oxley (Sir Hugo Baskerville), Francis De Wolff (Dr. Mortimer), Ewen Solon (Stapleton), John Le Mesurier (Barrymore), Miles Malleson (Bishop Frankland), Sam Kydd (Perkins), Helen Goss (Mrs. Barrymore), Judi Moyens (Servant Girl), Dave Birks (Servant), Michael Mulcaster (Selden), Michael Hawkins (Lord Caphill), Ian Hewitson (Lord Kingsblood), Elizabeth Dott (Mrs. Goodlippe). Sherlock Holmes (Peter Cushing) and Dr. Watson (Andre Morell) listen skeptically as Dr. Mortimer (Francis De Wolff) relates the legend of the Hound of the Baskervilles. A curse on the family was instigated by an evil ancestor, Sir Hugo (David Oxley), when he murdered a farm girl and was in turn killed by a spectral Hound. The recent mysterious death of Sir Charles has left Sir Henry Baskerville (Christopher Lee) heir to the fortune, and Mortimer fears for the baronet’s safety. Holmes interviews Sir Henry at his hotel, where he is angered by a missing boot and terrified by a tarantula. Due to Holmes’ heavy schedule, Watson accompanies Sir Henry to the Hall and meets the Barrymores’ (John Le Mesurier, Helen Goss) long-time family servants, the odd Bishop Frankland (Miles Malleson), who collects spiders, and the surly Stapleton (Ewen Solon) and his beautiful daughter, Cecile (Marla Landi).

Peter Cushing hams it up for the press while Anthony Hinds, Christopher Lee and Andre Morell look on during a pre-production visit to the Sherlock Holmes Pub in London (photo courtesy of Tim Murphy).

Watson is surprised to find Holmes on the moor where he has been since just after Watson arrived. Selden (Michael Mulcaster), an escaped convict (and Mrs. Barrymore’s brother), is killed by the Hound while he is wearing a suit of Sir Henry’s that she gave him. A chance remark by Watson causes Holmes to search for the Hound in a disused mine. He finds evidence of the beast, but is nearly killed by a cave-in. Sir Henry has fallen in love with Cecile, and as he walks with her across the moor, Holmes sets his trap. A portrait of Sir Hugo has revealed that Stapleton is a descendant and possible heir, and he and Cecile plan to kill Sir Henry with their savage dog. Holmes and Watson intervene; Stapleton is killed by the wounded Hound, and Cecile dies in the swamp. Back on Baker Street, Holmes reveals that the missing boot “put him on the scent.”

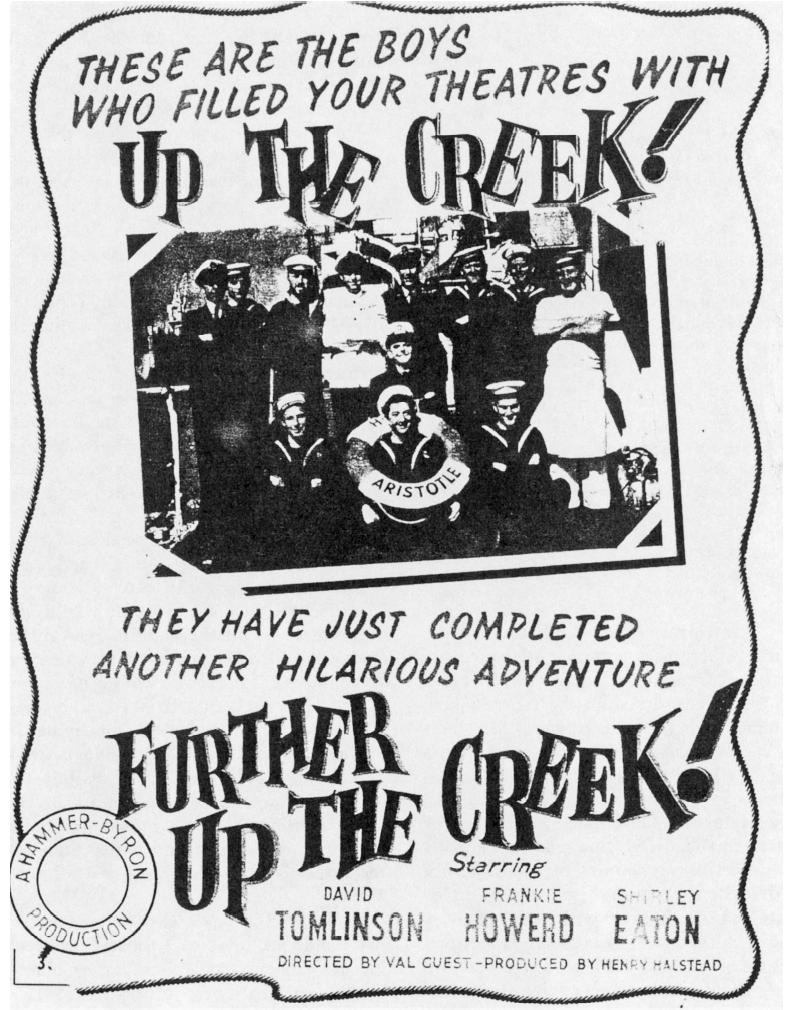

Dr. Watson (Andre Morell) and Stapleton (Ewen Solon) in The Hound of the Baskervilles.

Hammer’s intention to film Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous story, announced in early May, 1958, generated more excitement in the British trades than any of the company’s previous pictures. Naturally, there was speculation over who would play Holmes, but Hammer would not admit to any casting decisions, other than Michael Carreras’ hoping that Peter Cushing would be available. He and Christopher Lee were signed on August 1 (with Lee surprisingly cast as the hero), and Terence Fisher on August 7.

The company was just beginning its most productive period. A deal with Universal-International to remake its horror library was just completed, and a dozen projects were in various stages of development, including a reworking of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), which was never filmed. On September 3, Whitbread, an English brewery, hosted a party at the Sherlock Holmes Pub, located on the site of the Northumberland Hotel at which Sir Henry stayed in Conan Doyle’s novel. At the reception, the recently signed “Dr. Watson,” Andre Morell, was introduced to the press. “There are great hopes for this picture,” Terence Fisher told The Kinematograph Weekly (September 11, 1958). “Sherlock Holmes is a favorite all over the world. In fact, he’s so popular that half the people you speak to are not sure whether he really lived or not!” Anthony Hinds (The Daily Cinema, September 5) promised that Cushing would play Holmes as written—“realistically, not romantically.”

The Hound of the Baskervilles began production on September 8, 1958, but Marla Landi was added to the cast three weeks later. She was discovered by Anthony Hinds, who had seen her in a special screening of Across the Bridge, in which Landi had a featured role. Hammer’s search for the “title character” was recalled for the authors (August, 1993) by Margaret Robinson. “They had two dogs originally. One had been typecast because he once bit a barmaid! This was Colonel, who actually played the part. The other dog was owned by Barbara Wodehouse, and cost five times as much to hire. Also, Barbara wanted to double for Christopher Lee!” Robinson had been asked to design a mask for the dog, and when she measured the monster, “There was a girl sitting there all the time. I couldn’t understand why she was there. She finally said, ‘I’m the nurse!’ I made the mask out of a rabbit fur, and the dog wouldn’t allow anyone else to put the mask on him. He was a lovely dog—to me, at least!”

The greatest screen adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s classic.

On October 17, the main unit went on location to Frencham Ponds which stood in for the originally planned Dartmoor due to treacherous weather. “We decided it would be safer to find a location near Bray,” said Anthony Hinds (The Daily Cinema, October 8). During the location shoot, Peter Cushing was given a first edition of the novel by the manager of a local pub. “I’ve based all my costumes on the original Strand Magazine pictures,” Cushing said in The Evening Bulletin. “Everything is accurate right down to the old ‘mouse-colored’ dressing gown, which I charred with cigarettes to get the burns Holmes made during his experiments.” Cushing tried to avoid cliches associated with the character. “I am avoiding the more obvious props,” he said. He saw the character as “when on a case, like a dog following a scent. Holmes is not the pleasantest of characters either. He didn’t suffer fools, and he must have been insufferable to live with.”

Christopher Lee was eager to avoid being typecast and asked for the part of Sir Henry. “Although I was not entirely at all like the character created by the author, I felt I could create a similar personality,” he said in The Christopher Lee Club Journal “I felt that this was the time of possible danger for me; therefore, I deliberately chose to play Sir Henry, who was not the most exciting individual.” Although Lee has related a story about his terrifying encounter with the tarantula, Len Harris recalled it differently (August, 1993). “We got the spider from the London Zoo. She was twenty-five years old, and her name was Mary. Although she seemed to be harmless, we really couldn’t let her walk on Christopher Lee, and you can plainly see that he and Mary are never in the same shot.” Harris felt The Hound contained some of Jack Asher’s best photography. “He used colored gels to get his special color effects, but it took forever to set up and light a shot. He was a painter with light.”

During the final days of production, Fisher shot what was the most controversial scene, involving the Hound itself. Margaret Robinson recalled:

They duplicated the part of the set in miniature where the dog was to leap onto Sir Henry. A small boy named Robert was dressed to duplicate Christopher Lee. The dog couldn’t bear the sound of crumpled paper, and the idea was he would go straight for a propman as he crumpled it. What we didn’t know is that Colonel hated small boys, too! The prop man caught the dog in mid-air before he got to Robert.

Since the scene did not photograph properly, the idea was discarded altogether. One unexpected result of the scene was her meeting Bernard Robinson, whom she married in 1960.

The Hound of the Baskervilles was completed on October 31, and on March 31, 1959, Anthony Hinds and James and Michael Carreras flew the print to United Artists in New York and met with the American trade press. Hinds commented to The Daily Cinema (March 6) that everyone at Hammer was “tremendously excited. It has all the sensational box office qualities of its predecessors and is an exploiter’s dream subject.” The Sherlock Holmes Society of London called it “the greatest Sherlock Holmes film ever made.” The trade show was held at the Hammer Theatre on March 20, and The Hound of the Baskervilles premiered at the Pavilion on March 28 and demolished the theatre’s attendance record for a first week run. The general release was on May 4, with most reviews positive. The Daily Express (March 26): “A merry little romp”; The Daily Mirror (March 28): “Peter Cushing is a splendid Holmes”; The Daily Mirror (March 28): “There will be more Holmes films like this”; The Daily Cinema (March 23): “Beautifully made, gripping, exciting product”; The Standard (March 26): “Played effectively for a maximum of blood and thunder”; The New York Herald Tribune (July 4): “Sound version, nicely photographed and should be a pleasant introduction to the adventure”; and Variety (April): “It is difficult to fault the performance of Peter Cushing.”

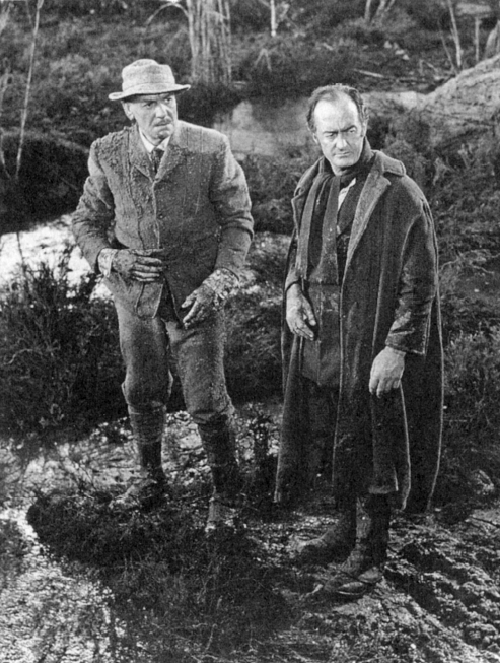

The man responsible for the Baskerville Curse, Sir Hugo (David Oxley) in The Hound of the Baskervilles.

Despite the positive reviews and box office results, Hammer chose not to develop a Holmes series. The film does have its detractors, mostly harping on Peter Bryan’s screenplay for not following the novel’s familiar path. Peter Cushing played Holmes on the BBC a decade later, and in the 1989 television film Masks of Death. As Anthony Howlett of the Sherlock Holmes Society said in The Daily Cinema (October 17, 1958), “Peter Cushing is perfect casting.”

Was this the best Holmes movie? Possibly. Is Peter Cushing the best Holmes? Probably. One point rarely argued is Andre Morell’s excellence as Watson. Why Hammer never followed The Hound of the Baskervilles with another Holmes picture remains a mystery. Although The Hound supposedly did not do as well as expected at the box office, its stature has grown considerably since.

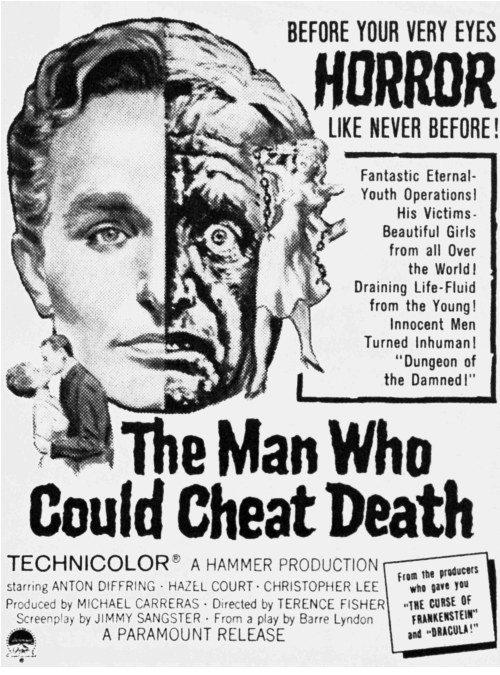

Released November 30, 1959 (U.K.), June, 1959 (U.S.); 83 minutes; Technicolor; 7488 feet; a Hammer Film Production; released through Paramount (U.K. and U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Terence Fisher; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Associate Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay: Jimmy Sangster, from Barré Lyndon’s play; Music: Richard Bennet; Musical Supervisor: John Hollingsworth; Director of Photography: Jack Asher; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Sound Recordist: Jock May; Continuity: Shirley Barnes; Editor: John Dunsford; Wardrobe: Molly Arbuthnot; Production Manager: Don Weeks; Assistant Director: John Peverall; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Hairstyles: Henry Montsash; U.K. Certificate: X.

A film more subtle than its advertising.

Anton Diffring (Bonner), Hazel Court (Janine), Christopher Lee (Gerard), Arnold Marle (Dr. Weiss), Delphi Lawrence (Margo), Francis De Wolff (Legris), Gerda Larsen (Street Girl), Middleton Woods (Little Man), Michael Ripper (Morgue Attendant), Denis Shaw (Tavern Customer), Ian Hewitson (Roget), Frederick Rawlings (Footman), Marie Burke (Woman), Charles Lloyd Pack (Man at Exhibit), John Harrison (Servant), Lockwood West (First Doctor), Ronald Adam (Second Doctor), Barry Shawzin (Third Doctor).

Victorian Paris. Amateur sculptor Dr. Bonner (Anton Diffring) has a terrible secret as he unveils the bust of his model Margo (Delphi Lawrence), who is also his lover. Although he looks 35, he is 104 years old, kept young through transplants of the parathyroid. Dr. Weiss (Arnold Marle), his famous partner, has not arrived to do the surgery, and Bonner is kept alive by a green fluid. Complicating matters are the arrival of his ex-lover Janine (Hazel Court) with her escort Dr. Gerard (Christopher Lee) and Margo’s petulance over the end of their love affair. After the party when she refuses to leave, Bonner, glowing greenly, sears her flesh with his hand. Weiss finally arrives. A stroke victim, he looks more than twice Bonner’s age, yet is 15 years his junior. Unable to perform the operation, he suggests that Bonner find a replacement and becomes concerned that Bonner has abandoned the experiment’s altruistic beginnings.

Bonner and Janine renew their affair, and, through Weiss, enlist Gerard’s help. When Weiss discovers that Bonner has killed to get the gland, he destroys the fluid, and in a rage, Bonner kills him. Gerard refuses to cooperate without the “missing” Weiss, so Bonner abducts Janine to force him to perform the surgery. When Bonner arrives at the old warehouse where he has hidden Janine, he realizes that Gerard has duped him. In an instant, Bonner assumes his true age with every disease he avoided and dies, set ablaze by the imprisoned Margo.

After Warner Bros. and Columbia struck gold with Hammer Horror, Paramount was next, unearthing their 1944 The Man in Half Moon Street for the Hammer treatment. Based on Barré Lyndon’s play, the original (starring Nils Asther) was a romantic mystery rather than a horror movie. Originally planned as Alan Ladd’s first starring role, the film betrayed its stage origins, as did the Hammer remake. Although its few horror elements were well-staged, The Man Who Could Cheat Death is more talk than action.

The fact that it is not as horrific as Dracula must be taken in context, since its approach is more cerebral than relying on dripping fangs.

Arnold Marle looks on as Hazel Court’s rivals, Anton Diffring (second from left) and Christopher Lee, meet in The Man Who Could Cheat Death.

Peter Cushing was “unavailable” for the lead, opening the door for Anton Diffring, who gave the role his usual chilly menace. He was typed as a “horror star” despite his infrequent appearances in genre films. Hazel Court played a role similar to her too trusting Elizabeth in The Curse of Frankenstein. She recalled for the authors (September, 1990):

At Hammer, you had to be good on the first take, which is the way they used quality actors even in small parts. We were all a happy family at Bray, not under the pressures of a big studio. We rehearsed a lot, like for a play, which is why we could do it on one take. There was a “European version” in which I’m nude to the waist when being sculpted. Today, it doesn’t mean a thing, but in those days it was something! I didn’t want to do it, but I thought “I’m supposed to be modeling, so I guess it’s OK.” It was all kept terribly secret! Hammer really opened things up. I loved doing the film. Anton was, unlike his image, a nice, charming man. Terence Fisher was a very professional, very competent director, comfortable and happy with horror. He had a job, and he did it, never promoting himself. We gave the audience more than they expected, and they sensed our dedication. That’s why the films are still popular, and I’m happy to have been a part of it. The Man Who Could Cheat Death was a beautiful movie.

Filming began on November 17, 1958, and concluded on December 30. To celebrate Hammer’s tenth anniversary of continuous production, a party was thrown on December 12, with a luncheon held at the Hinds Head Pub in Bray Village and a print of Dr. Morelle run at the studio. Following a June 4, 1959, trade show, The Man Who Could Cheat Death was released on November 30 on the ABC circuit, teamed with The Evil That Is Eve. The response from Variety

(June 24, 1959) was prophetic. “Well made but rather mild horror item, it is well acted and intelligently conceived. But invention and embellishment in this field appear to have been exhausted. As ever greater horror is required, there is less and less that is horrible enough.” This insightful review accurately predicted the genre’s fate by the early seventies. Other reviewers were less insightful. The Monthly Bulletin (July, 1959): “Offers little in the way of entertainment beyond the sets, costumes, and props”; The London Times (October 4): “It is all rather too wooden and stylized”; The Observer (October 4): “What dreary, lifeless work the concoction of these horror pictures must be”; The Star (October 1): “After … the intelligent and provocative Yesterday’s Enemy, and the well made The Mummy, the horror boys at Hammer films get back to ham and ketchup”; The Evening Standard (October 1): “Substandard”; and The Chronicle (October 10): “A flop.” The Kinematograph Weekly (June 11) stood practically alone in its praise: “A sure bet … fascinating and thrilling.”

While, admittedly, the film is not one of Hammer’s very best, the above seems harsh. Many of the negative reviews were aimed at horror movies in general. The Man Who Could Cheat Death seems to have been caught in the middle, and it was attacked for being both too tame and too gruesome. The film boasts some of Hammer’s most gorgeous sets and costumes, and the small cast is uniformly fine except for Christopher Lee’s uninspired playing of a blandly written part. Anton Diffring made the most of his starring role, but the film just misses. Interestingly, the American advertising played up Hammer’s name more than it did the cast members.