Released September 17, 1959; 95 minutes; B & W; 8550 feet; a Hammer Film Production; released through Columbia (U.K. and U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios/Shepperton Studios; Director: Val Guest; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Peter Newman; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Editors: James Needs, Alfred Cox; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Focus: Harry Oakes; Clapper/Loader: Alan McDonald; Grips: Albert Cowlard; Sound Recordist: Buster Ambler; Sound Cameraman: Jimmy Dooley; Boom: Peter Dukelaw; Sound Maintenance: Eric Vincent; Production Designer: Bernard Robinson; Assistant Director: John Peverall; Continuity: Cheryl Booth; Technical Advisor: Peter Newman; Assistant Art Director: Don Mingaye; Make-up: Roy Ashton: Wardrobe: Molly Arbuthnot; Hairdresser: Henry Montsash; Stills; Tom Edwards; Publicist: Colin Reid; Production Buyer: Eric Hillier; Special Effects: Bill Warrington, Charles Willoughby; Casting Director: Dorothy Holloway; Construction Manager: Jack Bolam; Electrical Engineer: S.F. Hillyer; Master Painter: S. Taylor; Master Plasterer: S. Rodwel; Master Carpenter: E.D. Wheatley; Property Master: Frank Burden; Floor Props: T. Frewer; Production Supervisor: T.S. Lyndon Haynes; Production Secretary: Doreen Jones; U.K. Certificate: A.

Stanley Baker (Capt. Langford), Guy Rolfe (Padre), Leo McKern (Max), Gordon Jackson (Sgt. McKenzie), David Oxley (Doctor), Richard Pasco (Lt. Hastings), Russell Waters (Brigadier), Philip Ahn (Yamazaki), Bryan Forbes (Dawson), Wolfe Morris (Informer), Edwina Carroll (Suni), David Lodge (Perkins), Percy Herbert (Wilson), Barry Lowe (Turner), Alan Keith (Bendish), Howard Williams (Davies), Timothy Bateson (Simpson), Arthur Lovegrove (Patrick), Donald Churchill (Elliott), Nicholas Brady (Orderly), Barry Steele (Brown).

Burma, World War II. A group of battered British soldiers slog through a swamp, separated from their company, and Captain Langford’s (Stanley Baker) temporary command is questioned by the Padre (Guy Rolfe) and Max (Leo McKern), a war correspondent. After a fierce battle, they take control of a village and begin interrogating the Burmese. A suspected informer (Wolfe Morris) refuses to divulge information about a mysterious map, so Langford orders two innocent villagers to be shot as examples. Most of the British are horrified by Langford’s brutality, and the informer’s revelation of a coming Japanese attack does little to relieve their disgust. Sgt. McKenzie (Gordon Jackson) then shoots the informer. Langford decides to warn the company of the attack and prepares to leave the village immediately, but their escape is halted by a Japanese attack. Now prisoners themselves, the British are subjected to the same brutality they previously inflicted on the Japanese. Col. Yamazaki questions Langford, who refuses to talk, so Lt. Hastings is placed in front of a firing squad to pressure Langford. He makes a clumsy attempt to use the radio and is shot. Wearily, Yamazaki orders the remaining British to be executed.

Gordon Jackson and Stanley Baker in Val Guest’s controversial World War II drama, Yesterday’s Enemy.

James Carreras said in the October, 1959, Films and Filming, “We hate message films. We make entertainment.” Since Yesterday’s Enemy was in release at the time, and Carreras had the final word on Hammer’s subjects, this was an odd statement. With the critical mauling of The Camp on Blood Island still fresh, one wonders why the company chose to return to World War II atrocities—and to point the finger of guilt at the British. Like many other Hammer films, Yesterday’s Enemy was adapted from a BBC production. Peter Newman’s play had caused a controversy and was a natural choice for a film. “I had many letters,” he told The Kinematograph Weekly (January 22, 1959). “Some were congratulating me; others accused me of being anti–British. Michael Carreras saw the play and contacted Val Guest.”

Guest told the authors (May, 1992),

Michael got a copy and let me have a look. I thought there was a hell of a picture in it. The film is one of my four favorites out of over ninety I’ve done—it was a labor of love. Stanley Baker was one of my favorites and was perfect. I did lay down one law—there would be no background music. The “score” was orchestrated with jungle noises and was, I believe, the first of its kind in England. The film was, for many reasons, controversial.

Yesterday’s Enemy began production at Shepperton on January 12, 1959, ended there on February 19, and then moved to Bray for completion. It was delivered to Columbia on May 5 as the first part of their “long-term agreement.” The Daily Cinema (January 12) felt the film would “arouse a great storm of controversy.”

A brutal look at war crimes—committed by both sides.

The production also aroused a great storm of problems beyond the unsettling subject matter. The construction of the village set was done on a wheeled section to achieve the illusion of changing spatial areas. A tank filled with slime was built at Bray to stand in as the swamp. The biggest problem, however, was the language barrier. The

Japanese soldiers were played by employees of London’s oriental restaurants and were mostly non–English speaking, so actor Philip Ahn had to interpret Val Guest’s directions. Len Harris recalled (December, 1993) that when one of the Japanese “soldiers” slipped and fell into the “swamp,” those in line followed, thinking they were directed to do so. Despite these and other problems (like almost blowing up a Shepperton sound stage), filming was completed on schedule.

The film had already made a great impression. The Daily Cinema (May 1) called it “the greatest Hammer has made.” James Carreras said, “It is to World War II what Journey’s End was to World War I.” (Journey’s End was a success on the London stage and in Hollywood [1930], directed by James Whale and starring Colin Clive who later collaborated on Frankenstein [1931].) Following a June 5, 1959, trade show, the film was shown to high ranking British army personnel. “I have never been so impressed or gripped by a film,” Maj. Gen. H.L. Davies said in a Hammer press release. “The character portrayal is magnificent, and there is a realism and authenticity about the background which is quite frightening.” Even the Japanese were moved. Lt. Col. Eich Tsuchiva, who led the assault on Burma, said, “The conflict between military discipline and humanitarianism and the cruelty of war are well expressed.”

Val Guest recalled in an interview with Tom Weaver that at the September 17, 1959, premiere at the Empire, “I sat next to Lord Mountbatten, and he kept nudging me. ‘I know where you shot that!’ he said. He was absolutely convinced that we shot it in Burma!” The world premiere had been held a week earlier in Tokyo. Before going into general release on the ABC circuit on October 19, the film was called “every exhibitor’s friend” in The Kinematograph Weekly (September 24). Critics were very positive, making Yesterday’s Enemy Hammer’s greatest critical success. The London Times (September 21, 1959): “A well-written film that stimulates argument … something of a surprise for those who associate Hammer Films with horror”; The Saturday Review (October 3): “serious, if not downright philosophical”; The New York Times (March 4, 1960): “haunting in the right way.”

Despite the excellent reviews and box office success, Yesterday’s Enemy was one of Hammer’s last “serious” productions. Its success led to an extension of the agreement with Columbia for the next five years, but inexplicably, the film has been forgotten. Leonard Maltin’s Movie and Video Guide (1993) gives the movie 1½ stars and calls it a “mild WW2 actioner,” hardly an apt description of this powerful, thought-provoking picture.

Released September 25, 1959 (U.K.), December, 1959 (U.S.); 88 minutes; Technicolor; 7903 feet; a Hammer Film Production; released through Rank (U.K.), Universal International (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Associate Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Jimmy Sangster, Director of Photography: Jack Asher; Music Composer: Frank Reizenstein; Music Director: John Hollingsworth; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Alfred Cox; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Masks: Margaret Carter Robinson; Camera: Len Harris; Production Manager: Don Weeks; Sound Recordist: Jock May; Hairstyles: Henry Montsash; Costumes: Molly Arbuthnot; Egyptology Advisor: Andrew Low; Assistant Director: John Peverall; Second Assistant: Tom Walls; Third Assistant: Hugh Harlow; Continuity: Marjorie Lavelly; Focus: Harry Oakes; Clapper: Alan McDonald; Boom: Jim Perry; Sound Camera Operator: Al Thorne; Sound Maintenance: Charles Bouvet; Assistant Art Director: Don Mingaye; Stills: Tom Edwards; Publicist: Colin Reid; Casting Director: Dorothy Holloway; Assistant Director: Chris Barnes; U.K. Certificate: X.

Peter Cushing (John Banning), Christopher Lee (Kharis), Yvonne Furneaux (Isobel/Ananka), Eddie Byrne (Inspector Mulrooney), Felix Aylmer (Stephen Banning), Raymond Huntley (Uncle Joe), George Pastell (Mehemet), Michael Ripper (Poacher), John Stuart (Coroner), Harold Goodwin (Pat), Dennis Shaw (Mike), Willoughby Gray (Dr. Reilly), Stanley Meadows (Attendant), Frank Singuineau (Head Porter), George Woodbridge (Constable), Frank Sieman (Bill), Gerald Lawson (Irish Customer), John Harrison (Priest), James Clarke (Priest), David Browning (Sergeant).

A very nervous Christopher Lee and friend in The Mummy.

Egypt, 1895. As archeologist John Banning (Peter Cushing) recuperates from a leg injury, his father, Stephen (Felix Aylmer), and uncle Joe (Raymond Huntley), enter the tomb of Princess Ananka despite the warning of Mehemet (George Pastell). Alone in the tomb, Stephen, while reading from the Scroll of Life, suffers a breakdown.

England, 1898. John is summoned to the Engerfield Nursing Home, where his father has spoken for the first time since being confined. He is disturbed to find Stephen babbling about a “living mummy” bent on their destruction. Nearby, Mehemet resurrects the four-thousand-year-old mummy of Kharis (Christopher Lee) from a swamp into which his coffin has sunk after a carriage accident. Kharis, Ananka’s High Priest—and lover, kills Stephen. After the inquest, John and his uncle pore over the Ananka legend, discovering that Kharis was sentenced to a living death after attempting to restore her to life via the Scroll—an act of blasphemy. The mummy is now an instrument of revenge against her tomb’s defilers, controlled by Mehemet who worships Karnak, Ananka’s ancient god.

Kharis kills Joe and, despite being shot repeatedly by John, escapes. When told of the attack, Inspector Mulrooney (Eddie Byrne) is skeptical, and unable to protect John when he is assaulted soon afterwards. But Banning is saved by his wife Isobel’s (Yvonne Furneaux) uncanny resemblance to Ananka. After confronting Mehemet at the Egyptian’s home, John is attacked again. When Mehemet orders Kharis to kill Isobel, the mummy turns against his master and carries Isobel to the swamp where he is shot to pieces by Mulrooney’s men, the Scroll of Life clutched in his hand.

After the spectacular success of Dracula, Universal-International gave Hammer remake rights to its library of horror classics. The first three on the list were The Mummy , The Phantom of the Opera (remade in 1962), and The Invisible Man (never produced). Al Daff, Universal-International President, and James Carreras had made one of the biggest deals ever between American and British film companies. Carreras described the agreement to Kinematograph Weekly (August 21, 1958) as “one of the greatest things that has ever happened to us.”

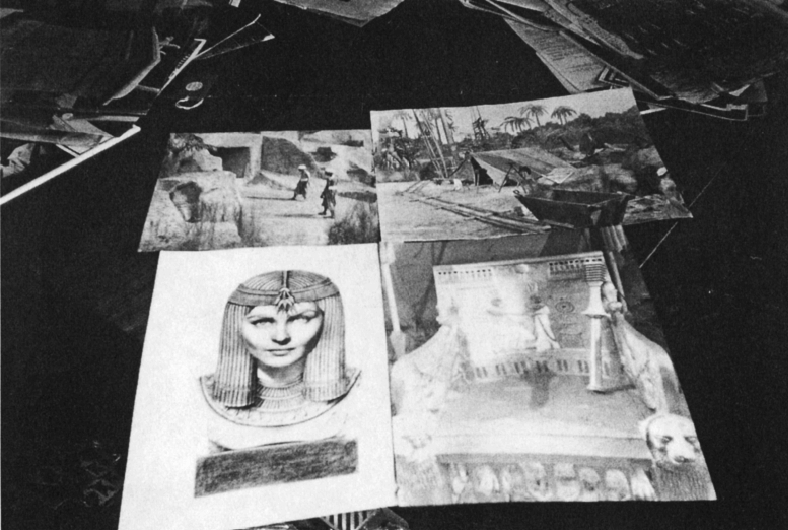

Bernard Robinson’s original designs for The Mummy (photo courtesy of Margaret and Peter Robinson).

The Mummy is often unreasonably compared to the 1932 Boris Karloff version, with which it has little in common. The movie is more sensibly compared to Universal’s 1940s series with Lon Chaney, Jr. “I must, at some point, have been shown these earlier Universal films,” Jimmy Sangster told the authors (August, 1993). “How else could one explain the same character names and plot elements? But I honestly don’t recall doing so—it has been thirty-five years, you know!” As the title character, Christopher Lee combines an awesome physical presence with a great sensitivity communicated through his eyes. Kharis is one of his best horror performances, second only to Dracula (and not by much). Peter Cushing could easily have been blown off the screen by Lee’s terrific performance, but he more than holds his own. The two stars have seldom been better paired, and according to The Daily Cinema (February 27, 1959), Universal-International considered their casting “a must.”

The Mummy began filming at Bray on February 25, 1959, concluding on April 16 with two weeks thrown in at Shepperton for the swamp scenes. During the production, Terence Fisher was headlined in The Kinematograph Weekly (March 26) with the oddly titled “I Don’t Make Horror Films.” Fisher noted: “Made with care, and at Bray, we take every care, these pictures are a genuine cinema form. I have always strenuously tried to avoid being blatant in my pictures. Instead, whenever possible, I have used the camera to show things—especially nasty things—happening by implication.” This is exactly the opposite reputation both Fisher (and Hammer) had unfairly developed. He was such an expert at the above that, as Harry Ringel pointed out in Cinefantastique, Fisher’s films often seemed more horrible than they really were.

Christopher Lee makes a startling entrance in The Mummy.

With typical Hammer efficiency, sets from Yesterday’s Enemy and The Man Who Could Cheat Death were quickly revamped. “Not only is this valuable in terms of financial outlay,” Anthony Nelson-Keys proclaimed in a press release, “but it means a terrific savings in time. We can go almost immediately from one production to another.” Hammer’s critics have often complained about “over used sets.” It is true that the company did cannibalize sets from one film to another, but rather than cut corners by giving audiences less, Hammer stayed on budget by this type of revision.

After an August 20, 1959, trade show at the Hammer Theatre, The Mummy premiered on September 25 at the London Pavilion (where the huge front-of-house display dominating Piccadilly Circus can be seen in Gorgo [1960], as the dinosaur is driven through London). In its first four days, The Mummy racked up the biggest business ever for a Universal-International/Rank picture at the prestigious theatre. After leaving the Pavilion on October 23, the picture went into general release on the ABC circuit, smashing records set the previous year by Dracula. Hammer, Universal-International, and Rank got behind the film by scheduling personal appearances by the cast and Egyptologist/technical advisor Andrew Low throughout the U.K. “I believe the real reason for Hammer’s success,” said publicist Philip Gerard in The Kinematograph Weekly (September 3, 1959), “is because Jimmy Carreras and Tony Hinds are real showmen. These men have built for Hammer an enviable reputation in American film circles by delivering a box office product which represents the best in its class.”

Despite the care (courtesy of Andrew Low) given to The Mummy, the film was not without lapses. Margaret Robinson told the authors in August, 1993, “I pointed out to Michael Carreras that Karnak was a place, not a god. He told me, ‘Don’t worry. No one will know the difference.’” She had more difficulty making the Anubis mask for the burial procession. “The actor hadn’t been cast yet, so I made a large mask, assuming the actor would be a big one. After the mask was completed, he came into my room—the largest Turk I ever saw! The mask was quite rigid, stiffened by piano wire; and after he struggled into it, I saw a trickle of blood run down his neck.”

Hammer brings the Mummy saga back for a new generation of fans.

Reviews for The Mummy reflected its box office power. The London Times (September 28, 1959): “Hammer Films have made the most distinguished of English horror films, partly because of an imaginative use of photographic and Eastman color devices, and partly by the employment of excellent actors”; The Observer (September 27): “Well tried ingredients plus an Egyptological know how”; The Evening Standard (September 9): “Excellently mounted, well acted, highly entertaining”; The Kinematograph Weekly (August 13): “Spectacular. Gripping story, first rate characterization, star value”; The Daily Cinema (August 7): “A sure-fire box office attraction”; The New York Herald Tribune (December 17): “The climax is properly frantic”; and Variety (July 15): “Well produced.”

In America, The Mummy was released with Universal-International’s offbeat vampire western, Curse of the Undead, making one of the decade’s best horror double features. While not Hammer’s greatest horror, it is close behind Dracula. The two were re-issued in the U.K. in 1964 to over 1500 bookings and broke many house records.

Released August 10, 1959 (U.K.); 84 minutes; B & W; 7528 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a Columbia Release; filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Lance Comfort; Associate Producer: Tommy Lyndon-Haynes; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Sid Colin, Jack Davies, based on Colin’s story; Director of Photography: Michael Reed; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: John Dunsford; Music: Douglas Gamley; Art Director: Bernard Robinson; Production Manager: Don Weeks; Production Secretary: Patricia Green; 1st Assistant Director: John Peverall; 2nd Assistant Director: Tom Walls; 3rd Assistant Director: Hugh Harlow; Continuity: Marjory Lavelly; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Focus: Harry Oakes; Clapper/Loader: Alan MacDonald; Sound Mixer: Jock May; Boom Operator: Jim Perry; Sound Camera Operators: Al Thorne, Michael Sale; Sound Maintenance: Charles Bouvet; Sound Assistant: Maurice Smith; Assistant Art Director: Don Mingaye; Stills Cameraman: Tom Edwards; Publicist: Colin Reid; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Hairdresser: Henry Montsash; Wardrobe Mistress: Molly Arbuthnot; Wardrobe Assistant: Rosemary Burrows; Casting Director: Dorothy Holloway; Assistant Editors: Peter Todd, Alan Corder; Chief Accountant: W.H.V. Able; Cashier: Peter Lancaster; Studio Manager: A.F. Kelly; Construction Manager: Mick Lyons; Chief of Electricians: Jack Curtiss; Master Painter: Lawrence Wrenn; Master Plasterer: Arthur Banks; Property Master: Tommy Money; Production Buyer: Eric Hillier; Floor Props: Peter Allchorne; Electrical Supervisor: George Robinson Cowlard; Associate Producer’s Secretary: Margot Wardle; Transport Drivers: Coco Epps, Wilfrid Faux, Sid Humphrey; U.K. Certificate: U.

Poster from The Ugly Duckling (courtesy of Fred Humphries and Colin Cowie).

Bernard Bresslaw (Jeckyll/Hyde), Reginald Beckwith (Reginald), Jon Pertwee (Victor), Maudie Edwards (Henrietta), Jean Muir (Snout), Richard Wattis (Barclay), David Lodge (Peewee), Elwyn Brook-Jones (Dandy), Michael Ripper (Fish), Harold Goodwin (Benny), Norma Marla (Angel), Keith Smith (Figures), Michael Ward (Pasco), John Harvey (Sgt. Barnes), Jess Conrad (Bimbo), Mary Wilson (Lizzie), Jeremy Phillips (Tiger), Vicky Marshall (Kitten), Alan Coleshill (Willie), Jill Carson (Yum Yum), Jean Driant (Blum), Nicholas Tanner (Commissionaire), Shelagh Dey (Miss Angers), Sheila Hammond (Receptionist), Verne Morgan (Barman), Ian Wilson (Small Man), Cyril Chamberlain (Police Sergeant), Ian Ainsley (Fraser), Reginald Marsh, Roger Avon, Richard Statman (Reporters), Robert Desmond (Dizzy), Alexander Dore (Customer).

Dandy Kingsley (Elwyn Brook-Jones) leads a gang of jewel thieves—Fish (Michael Ripper), Peewee (David Lodge), and Benny (Harold Goodwin)—and also manages the Palais, a suburban dance hall. His main attraction is Henrietta Jeckyll’s (Maudie Edwards) Old Time Dancing Team. The Rockets, a teen gang led by Bimbo (Jess Conrad) and his girl Angel (Norma Marla), are regulars. Henrietta’s plain brother Henry (Bernard Bresslaw), one of her dancers, is a constant butt of insults from the Rockets. During the performance, Dandy is questioned by Inspector Barclay (Richard Wattis) about a jewel heist. The next day, Snout (Jean Muir), a sympathetic Rocket, promotes Henry, unsuccessfully, for membership. When Henrietta and Victor (Jon Pertwee), another brother, leave for the Palais, Henry is left to manage the family chemist shop—and finds the secret formula of his famous relative.

Now, as the swinging Teddy Hyde (with sideburns, a mustache, and dressed like a gangster), he goes to the Palais and moves in on Angel. When Bimbo objects, Teddy knocks him out. Dandy is impressed and offers Teddy a place in his gang, but he awakens the next morning as Henry with no memory of the previous night. He transforms again and later takes part in the robbery. Victor has discovered his secret and, with Snout’s help, convinces Henry to return the jewels and turn in the gang. Henry, now wearing a Rockets jacket, becomes manager of the Palais.

Although The Ugly Duckling has seemingly vanished, it lives on in its basic concept of a dashing Mr. Hyde in Hammer’s own The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll and Jerry Lewis’ The Nutty Professor (1963). Michael Carreras described the film (The Kinematograph Weekly, November 20, 1958) as “A tailor made subject for Bernard Bresslaw. We believe it will be one of the year’s funniest comedies.” A March 12, 1959, follow-up revealed—incredibly—that the comedy “will be followed later in the year by a ‘straight’ version.” Initially titled Mad Pashernate Love, the picture began production on May 4 and concluded on June 10. During the filming, James Carreras (The Daily Cinema, May 11) revealed Hammer’s own “secret” formula for success. “We make exploitable pictures. What we have done, others can do. There’s no magic involved. It’s true we did evolve a horror formula, but we have made other kinds of films as well—and they have been equally successful.” He indicated that Hammer had no intention of going into television. “We’re taking the best from television,” he said. Michael Carreras addressed the wisdom of making both a comedy and straight version of the same story in The Kinematograph Weekly (May 28): “The two treatments are so far apart as to be practically unrecognizable. The Ugly Duckling will do the straight version some good. It will reacquaint people with the names Jekyll and Hyde.” Director Lance Comfort noted that Bresslaw metamorphosed by the “shedding of a comedy appearance for the Hyde character. There was no tendency to laugh when he emerged.” The picture’s musical segments had Michael Carreras eyeing a “new style musical” that went unproduced.

Following a July 28, 1959, trade show at the Columbia Theatre, The Ugly Duckling went into general release on August 10 to less than admiring reviews. The Daily Cinema (July 29): “Little more than a peg on which to hang a series of slapstick gags”; The Monthly Bulletin (September): “Only intermittently and moderately amusing”; The Daily Herald (August 6): “The world’s top horror specialist has decided to take the mickey out of the subject that made them famous.” The picture was “well patronized by juveniles,” but apparently by no one else. The picture itself is virtually impossible to see and goes unmentioned in most film guides. The movie would be worth seeing, if only for its role in spawning Hammer’s most interesting failure later that year.

Released January 18, 1960 (U.K.), May, 1960 (U.S.); 81 minutes (U.S.); B & W; Strangloscope; 7238 feet; a Hammer Film Production in association with Kenneth Hyman; a Columbia Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Associate Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay: David Z. Goodman; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Camera: Len Harris; Editor: Alfred Cox; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Music: James Bernard; Musical Director: John Hollingsworth; Art Director: Bernard Robinson; Assistant Art Director: Don Mingaye; Sound: Jock May; Assistant Director: John Peverall; 2nd Assistant Director: Tom Walls; Technical Advisor: Michael Edwardes; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Production Manager: Don Weeks; Hairdresser: Henry Montsash; Personnel Advisor: Jimmy Vaughn; Continuity: Tilly Day; Stills Cameraman: Tom Edwards; Wardrobe Mistress: Molly Arbuthnot; Publicist: Dennison Thornton; U.K. Certificate: X.

Guy Rolfe (Captain Harry Lewis), Allan Cuthbertson (Captain Connaught-Smith), Andrew Cruickshank (Colonel Henderson), George Pastell (High Priest), Marne Maitland (Patel Shari), Jan Holden (Mary Lewis), Paul Stassino (Lt. Silver), Tutte Lemkow (Ram Das), David Spenser (Gopali), John Harvey (Burns), Roger Delgado (Bundar), Marie Devereux (Karim), Michael Nightingale (Sidney Flood), Margaret Gordon (Dorothy Flood), Steven Scott (Walters), Jack McNaughton (Corporal Roberts), Ewen Solon (Camel Vendor), Mongoose (Toki).

Hammer’s attempt at historical horror.

In the 1820s, the British East India Company turns to the British military for help in combatting the brigands responsible for the hijacking of caravans and the disappearance of over 1,000 travelers. Captain Lewis (Guy Rolfe) volunteers to head the investigation but the assignment instead goes to an overbearing, ineffective newcomer, Captain Connaught-Smith (Allan Cuthbertson). The terrorists belong to a fearsome religious cult—the Thuggees—worshippers of Kali who strangle and rob their victims and bury their bodies in mass graves. When the cult’s high priest (George Pastell) marks Lewis for death, Lewis battles off an attacker and later resigns from the company in order to fight the cult with a freer hand. After another caravan is attacked and plundered, Lewis trails the Thuggees to their temple, where he is captured and condemned to be thrown alive onto a blazing funeral pyre. But one of the cult’s new initiates (David Spenser), haunted by conscience after having killed his own brother (Lewis’s former servant) at the high priest’s command, cuts Lewis’s bindings. Lewis and the high priest fight and the priest topples into the pyre. Their leader dead, the other cultists run off, but Lewis—restored to his former rank—knows that the army’s war against the Thuggees is only beginning.

Hammer’s pseudo-historical film about the Indian cult of “Thuggee” was one of the few to deal with the topic, perhaps due to the ferocity of the subject. During the cult’s three-hundred-year reign of terror, over one million people were sacrificed to Kali. Originally titled The Horror of Thuggee, the film’s production was announced on September 17, 1958, in The Daily Cinema. Michael Carreras called the script “the most exciting and incredible story.” Author David Z. Goodman’s months of research resulted in a finished script a week after the announcement. Based on W.H. Sleeman’s actual attempts to destroy the cult, Goodman’s script was heavily censored for its brutality—stomach slittings, corpse mutilations, and burnings—and the “overuse” of curse words. As of December, Hammer still planned to shoot the film in color, an idea later abandoned.

Anthony Nelson-Keys was appointed General Manager of Bray Studios in April, 1959. He joined Hammer in 1956, and was promoted due to the increased production caused by the Columbia pact. After a title change to The Stranglers of Bengal, production on The Stranglers of Bombay began on July 6. With Michael Carreras on vacation in Spain, Anthony Hinds supervised the filming which ended on August 27. Although the movie had no star actors, its subject matter and the Hammer name were thought to be enough. Fortunately for Hammer—but not for India—there was a renewal of cult activity after a one-hundred-twenty-year silence. When the company delivered a rough cut to Columbia, James Carreras said (The Daily Cinema, September 28), “In The Stranglers of Bombay, we have delivered the strangest and most exciting action picture we have ever made.” The film premiered at the London Pavilion on December 4, and went into general release on the ABC circuit on January 18, 1960. Critics were duly horrified, as they would be in America, when the movie opened, paired with Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana in May. The Evening Standard (December 3, 1959): “Hardly my idea of a jolly entertainment theme”; The Monthly Film Bulletin (January, 1960): “The usual fleabitten affair relying almost entirely for its appeal on visual outrages”; Films and Filming (February): “It is no pleasure to record as a critic that something so unhealthy is well done, which it is”; The Daily Worker (December 5, 1959): “The extraordinary thing is that the background is much more authentic and intelligently handled than many a great glamour epic about the glories of the East”; and The Kinematograph Weekly (December 3, 1959): “Exuberant adventure melodrama.”

The Stranglers of Bombay helped to solidify the reputations of both Hammer and Terence Fisher as purveyors of sadism. According to Harry Ringel (Cinefantastique, Vol. 4, No. 3), “The film appalled even its director when he came to see it finished.” The Stranglers of Bombay was Hammer’s most realistic horror, and Fisher showed he could jolt an audience without Technicolor, blood, or Christopher Lee. Guy Rolfe headed a fine cast, Bray stood in admirably for the “mysterious East,” and James Bernard contributed an atypical but rousing score to make the film a valuable component of Hammer’s most exciting period.

Released December 21, 1959 (U.K.); 85 minutes; B & W; 7612 feet; a Hammer-A.C.T. Production; a Columbia Release; filmed at Walton Studios, and on location at Chobham Common and Thurlestone; Director: George Pollock; Executive Producer: Ralph Bond; Producer: Teddy Baird; Screenplay: Jack Davies; Original Play: Michael Corston, Ronald Holroyd; Director of Photography: Arthur Graham; Art Director: Scott MacGregor; Editor: Harry Aldous; Production Manager: Clifford Parkes; Music Composed and Conducted by: Philip Green; Camera Operator: Eric Besche; Sound Camera Operator: Alan Hogben; Sound Recordist: Sid Wiles; Makeup: Peter Aramsten; First Assistant Director: Douglas Hermes; Assistant Art Director: Tom Goswell; U.K. Certificate: U.

Dennis Price (Krisling), George Cole (Finch), Thorley Walters (Brown), Harry Fowler (Ackroyd), Nadja Regin (Elsa), Nicholas Phipps (Mortimer), Percy Herbert (Bolter), George Murcell (Meister), Gerlan Klauber (Schmidt), Terence Alexander (Babbington), Thomas Foulkes (Voss).

World War II, somewhere in the Adriatic Sea. Both the Germans and British want control of an island to use as an observation post. Second Lt. Brown (Thorley Walters), Sgt. Bolter (Percy Herbert), and Pvts. Ackroyd (Harry Fowler) and Finch (George Cole) are sent to take charge, but are abandoned without supplies and forgotten. Unfortunately, four Germans, also marooned, have a camp on the other side. Capt. Von Krisling (Dennis Price), Sgt. Schmidt (Gerlan Klauber), and Pvts. Meister (George Murcell) and Voss (Thomas Foulkes) soon meet the Brits and agree to a truce.

Finch and Voss are archeologists and do some excavating, but Von Krisling and Brown become testy when Elsa (Nadja Regin) washes ashore and both sides “claim” her. Luckily, both groups are picked up by submarines.

From 1956 to 1959, Hammer made as many military pictures as horror movies. Don’t Panic Chaps was the company’s fourth service farce—a popular fifties subgenre in both Britain and America, due to the vast number of adults who had been in the War and still held a grudge against someone. It is debatable whether these films “traveled well” due to the dissimilarities between the way the military is perceived on either side of the Atlantic. Hammer and A.C.T. Films joined forces to adapt Ronald Holroyd and Michael Corston’s radio play in July, 1959, on a six-week schedule with a £75,000 budget. Producer Teddy Baird said in The Kinematograph Weekly (August 13, 1959), “I welcome these small budget productions. I think we could be making them for even less without sacrificing quality. This is not the time for taking expensive risks.” The British Film Industry (except for Hammer) had been in a minor slump, explaining Baird’s reticence.

Don’t Panic Chaps poster (courtesy of Fred Humphries and Colin Cowie).

Director George Pollock pointed out that despite the temptation to deliver a message about peaceful co-existence, he was playing the film for laughs. “There is this underlying note of seriousness,” he told The Daily Cinema (October 21, 1959), “but we’re certainly not making a thing of it.” James Carreras added, “It’s our funniest film yet!” A trade show was held on November 24, 1959, at the Columbia, and Don’t Panic Chaps was released on the ABC circuit on December 21 to favorable reviews. The Daily Express (December 19): “A good old Army comedy with never a serious moment”; The Daily Cinema (November 27): “A welcome, though unstressed, moral of peace among men”; The Kinematograph Weekly (November 26): “Wholesome, if artless humor.” Interestingly, the American Variety panned the picture.

This was a busy time for Hammer, and in the rush, the company may have missed a major opportunity. Announced, but never filmed, was The San Siado Killings with Stanley Baker, to be shot in Spain. The picture sounds as though it could have been the first “spaghetti western.”

Released March 4, 1960 (U.K.); 81 minutes; B & W; Hammerscope; 7292 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a Columbia Release; filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Cyril Frankel; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: John Hunter, based on Roger Caris’ play The Pony Cart; Director of Photography: Freddie Francis; Music Composed by Elizabeth Lutyens; Musical Director: John Hollingsworth; Production Designer: Bernard Robinson; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Editor: Alfred Cox; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Associate Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Sound Recordist: Jock May; Production Manager: Clifford Parks; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Hairdresser: Henry Montsash; Continuity: Tilly Day; Wardrobe Mistress: Molly Arbuthnot; Assistant Director: John Peverall; Second Assistant: Ron Wall; Casting Director: Dorothy Holloway; Stills Cameraman: Tom Edwards; U.S. Title: Never Take Candy from a Stranger; U.K. Certificate: X.

Gwen Watford (Sally), Patrick Allen (Pete), Felix Aylmer (Olderberry Senior), Niall MacGinnis (Defense Counsel), Alison Leggatt (Martha), Bill Nagy (Olderberry Junior), Macdonald Parke (Judge), Michael Gwynn (Prosecutor), Bud Knapp (Hammond), Janine Faye (Jean), Frances Green (Lucille), James Dyrenforth (Dr. Stephens), Estelle Brody (Eunice), Robert Arden (Tom), Vera Cook (Mrs. Demarest), Cal McCord (Kalliduke), Gaylord Cavallaro (Phillips), Sheila Robins (Miss Jackson), Larry O’Connor (Sam), Helen Horton (Sylvia), Shirley Butler (Mrs. Nash), Michael Hammond (Sammy Nash), Patricia Marks (Nurse), Peter Carlisle (Usher), Mark Baker (Clerk), Sonia Fox (Receptionist), John Bloomfield (Foreman), Charles Maunsell (Janitor), Andre Daker (Chauffeur), Bill Sawyer (Taxi Driver), Jack Lynn (Dr. Montfort), William Abney (Trooper), Tom Bushby (Policeman).

Two children—Jean (Janine Faye) and Lucille (Frances Green)—are lured into his home by Mr. Olderberry (Felix Aylmer), a perverted old man. Jean’s father, Pete (Patrick Allen), has just brought his family to the small Canadian town after being hired as the high school principal. That night, Jean tells him and her mother, Sally (Gwen Watford), she stepped on a nail while dancing nude for Olderberry. Rather than call the police, Pete tries to deal with Olderberry’s son, Richard (Bill Nagy), but after Jean suffers a nightmare, he contacts Captain Hammond (Bud Knapp). The Captain is of little use, intimidated by Olderberry’s power in the community. Worse, he hints that this is not the first such incident. When Pete confronts Richard, he threatens to remove Pete from his new position.

The case goes to court, but goes badly. Despite the efforts of the Prosecutor (Michael Gwynn), the Defense (Niall MacGinnis), bullies Jean. The Judge (Macdonald Parke) ends the proceedings to “protect” her, releasing Olderberry. Pete resigns, and as Jean says goodbye to Lucille, they are assaulted by Olderberry. As they try to escape him in a rowboat, they find it is attached to the pier as he reels them in.

A search party finds Lucille’s body in an old cabin, but Jean is found, safe, in the forest. Olderberry is taken away while Richard goes to Lucille’s house to face her parents.

James Carreras’ comment that “We hate message films. We make entertainment” (Films and Filming, October, 1959) never applied less than to this film. The movie’s failure to be accepted seriously put an end to the company’s fling with adult drama, and with very few exceptions, Hammer would never again attempt a higher goal than to entertain. Based on Roger Caris’ play The Pony Cart, Never Take Sweets from a Stranger not only confronted the horror of child molestation, but its sanction by a dysfunctional community. Despite Hammer’s obvious sincerity and restraint, the film might have been better accepted if made by another company, as Hammer’s growing reputation for sensationalism worked against it. Also, during this period, child molestation was rarely discussed at all, and certainly not in a movie.

Filming lasted from September 14 to October 30, 1959, at Bray and Black Park. Due to the touchy subject, Carreras was relieved to get a congratulatory telegram from Columbia head Mike Frankovich, in mid–February, 1960, after a screening in New York. The trade show was held on February 26 at the Columbia, after which the film was endorsed by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The Rev. Arthur Morton proclaimed it “deeply moving” (The Daily Cinema, February 28), and planned to tour with the film in the U.K. Release was on March 4, 1960, at the Pavilion, and the unforeseen critical attacks began. The London Times (March 7): “It must be condemned as a film that never should have been made”; Films and Filming (May): “A smart production veneer might fool people into thinking that here is a wholly adult film concerned with social and moral problems. It isn’t! In years to come, film historians will no doubt be able to logically explain the success of this company dealing only with the lurid and the loathsome.” Balancing these over-reactions were praise from Scotland Yard, the NSPCC (“The producers are to be congratulated on their objective presentation”) and juvenile defense expert Sir Basil Enrigues (“A most enthralling film of great human interest”).

A more serious problem occurred when Columbia tried to open the movie in America. Variety (May 15, 1960) reported, “Production Code Administration rejection of the Columbia import had been upheld by the Code’s review board, finding the picture to violate the edict about the depiction of sexual perversion.” Appearing for Columbia was Vice President Paul N. Lazurus, who argued that the film “is a discussion of sex in good taste and could render a meaningful public service.” A month earlier, Variety (March 16) gave the film a positive review. “A sincere, worthy, restrained, and exceedingly well done job which should be seen by every parent and child.” A year later, Variety (March 15, 1961) would report that the National League of Decency was in support of the picture. “This is a perennial social problem treated with moral caution and without sensationalism.” But it was too late—the damage was done. Infrequent showings at metropolitan area “art houses” were the only way to see the film in America.

British reviewers remained mostly appalled. The Sunday Express (June 3, 1960): “The treatment is too glib, its style too melodramatic, an easy profit out of an important but nasty subject”; and The Daily Mail (April 3): “A workaday thriller pivoting on the activities of a sex maniac.” Supporting the picture were The New Statesman (September 4, 1960): “A Hammer Horror on its best behavior”; The Daily Express (April 13): “I cannot accuse Hammer of sensationalism or indeed of any lapse of good taste”; and The Daily Herald (April 3): “This film could save your child’s life.”

Janine Faye had originally auditioned for the stage version but, because of her age (10), was rejected because it was felt the subject matter was too risque. When Cyril Frankel interviewed over 100 children for the film, he said in The Kinematograph Weekly (September 12, 1960): “When I cast a child, previous acting experience is the least important requirement. If a child has acted before, I break that down and start from scratch.” Faye was given a fair opportunity and won the role.

Never Take Sweets from a Stranger was the first Hammer film for Freddie Francis, who would soon become one of the company’s main directors. He was one of Britain’s top cinematographers, winning an Oscar for Sons and Lovers (1960). He told Wheeler Dixon, “It was a problem film. It wasn’t designed to be a commercial success.”

Even today, this is a difficult movie to find, but thanks to Dick Klemensen, the authors got to see a letterboxed video. The first thing one notices is that there is no attempt at sensationalism—the film could easily be shown as an afternoon television special. The only scene geared to shock involves Mr. Olderberry slowly reeling in the rowboat, and it is chilling. Felix Aylmer, who never speaks, is excellent, as is the rest of the cast. It is unfortunate that this film has become an obscurity. Michael Carreras (The Horror People) summed up the situation. “The moment the film came out the critics said, ‘Oh, here we go—look at Hammer taking a social problem and capitalizing on it.’ There was never any attempt to exploit the subject.”

Released May 1, 1960 (U.K.), January 18, 1961 (U.S.); 98 minutes (U.K.), 93 minutes (U.S.); B & W; Hammerscope; 8803 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Associated British–Warner Pathe Release (U.K.); a Columbia Release (U.S.); filmed on location in Manchester; Director: Val Guest; Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Val Guest, based on Maurice Proctor’s novel; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Music: Stanley Black; Editors: James Needs, John Dunsford; Art Director: Robert Jones; Production Manager: Don Weeks; Sound: Leslie Hammond, Len Shutton; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Makeup: Colin Garde; Hairstyles: Pauline Trent; U.K. Certificate: A.

Stanley Baker (Martineau), John Crawford (Starling), Donald Pleasence (Hawkins), Maxine Audley (Julia Martineau), Billie Whitelaw (Chloe), Joseph Tomilty (Steele), Vanda Godsell (Lucky), Geoffrey Frederick (Constable Devery), Sarah Branch (Silver), George A. Cooper (Savage), Charles Houston (Roach), Joby Blanshard (Jakes), Charles Morgan (Lovett), Peter Madden (Darwin), Dickie Owen (Bragg), Lois Dane (Cecily), Warren Mitchell (Traveller), Alastair Williamson (Sam), Russel Napier (Superintendent).

Detective Inspector Martineau (Stanley Baker) must deal with the jailbreak of Don Starling (John Crawford) in addition to his failing marriage to Julia (Maxine Audley). Martineau had earlier arrested Starling for a jewel robbery, and the thief is out for revenge. After questioning Lucky (Vanda Godsell), Starling’s former lover, Martineau is made aware that she is “available” to him whenever he wants her. Starling returns to Manchester and rejoins his old mob. The first victim is bookmaker Gus Hawkins (Donald Pleasence). They kidnap his clerk (Lois Dane), rob her of £4,000, and when she screams, kill her. Needing a hideout, Starling contacts another ex-lover, Chloe (Billie Whitelaw)—Mrs. Gus Hawkins. She allows him to stay; but after he assaults Gus, she reports him to Martineau. She also ties him into the killing due to his green fingers, stained by an exploding dye.

After raiding an illegal gambling event in which some of the dyed notes are passed, Martineau apprehends the gang. Starling breaks into Steele’s (Joseph Tomilty) warehouse in which he hid the stolen jewels. Startled by Steele’s handicapped granddaughter (Sarah Branch), Starling shoots her. Martineau chases Starling across the rooftops, and both are injured by gun-fire.

On the day of Starling’s execution, Martineau and Julia quarrel. Following a brief talk with Lucky, he walks the streets alone.

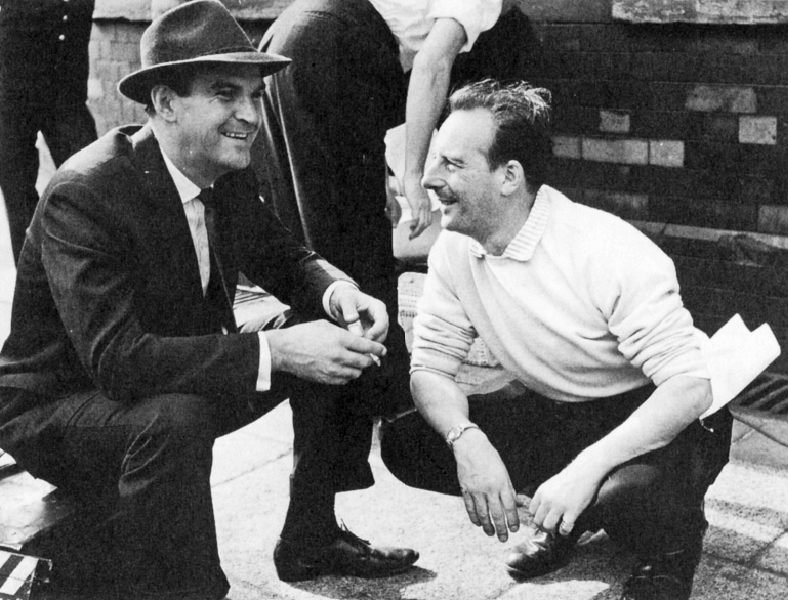

Stanley Baker (left) and Val Guest on the set of Hell Is a City.

“Hell Is a City,” Val Guest told the authors (May, 1992), “is one of my favorite films. It began as a book that Michael Carreras read. He was a brilliant guy—he had foreseen all sorts of directions for Hammer. I read it too, at his suggestion, and thought it would make a really unusual police picture where it didn’t just ‘slot in’ that everything went right. I specifically asked for Stanley Baker, since we worked so well together on Yesterday’s Enemy.”

Part of Carreras’s “direction” included a continued diversification of product, even after the success of the horror films. Unfortunately, this ended by the mid-sixties at which time Hammer became totally identified with horror/fantasy. But that was years away, and the company was still mixing the occasional adult drama in with its more exploitative subjects.

The Daily Cinema (September 2, 1959) announced that “For the first time, Hammer is to produce a feature for release through A.B. Pathe which will be shot largely on location in Manchester.” Filming began on September 21, and when The Daily Cinema visited the set on October 15, Stanley Baker described the half-finished film as “the psychology of a battle between two powerful individuals on the streets of a recognizable city.” The original intention had been to call the city “Grantchester,” but Manchester officials insisted on the actual name being used and Hammer had the complete cooperation of all city departments.

One of Hammer’s concerns was to avoid an X rating due to some nasty violence and very brief nudity that Val Guest felt necessary to convey the realism he sought. This realism distinguished Hell Is a City from most other Hammer films. As in Guest’s other pictures for the company, there is no sensationalism, and his restraint was rewarded with an A rating. Filming ended on November 5, 1959, and a trade show was held on March 11, 1960, followed by a special “northern premiere” in Ardwick on April 10. Hell Is a City went into general release on May 1 among the best reviews ever given to a Hammer film. Unfortunately, the name “Hammer” was seldom mentioned. The London Times (May 2, 1960): “Mr. Guest has directed with a powerful sense of tempo”; The Monthly Bulletin (May): “It has a striking outdoor appearance”; The Daily Express (April 29): “Crime par excellence”; The Star (April 28): “A cops and robbers film with a difference”; Variety (May 18): “One of the best British films in some time”; The New York Times (January 19, 1961): “A respectable job with a minimum of nonsense”; and The New York Herald Tribune (January 19): “Superior to what one finds in most such films.”

Hell Is a City gave Stanley Baker his second excellent role for Hammer, but he quickly moved out of their price range after Zulu (1964). The picture’s best performance is Billie Whitelaw’s, who has a fleeting nude scene—Hammer’s first in a British print. This flirtation with nudity would become, by the decade’s end, a full-blown romance, but in this case it was not exploited.

Hell Is a City was Val Guest’s last outstanding film for Hammer, and much of the company’s success was due to his versatility. He was to Hammer what Michael Curtiz had been to Warner Bros. Guest told the authors,

I would say it was one of the happiest periods of my life. We were one big happy family—especially down at Bray—very happy days and also, because of the lack of money and space—you had to learn your job so that you could make something look like a million when you only had ten to spend.

It was a question of coming in the morning with “instant genius.” We all used to say, “Have you brought your instant genius pills this morning?” They were great, great days, and we learned an awful lot—all of us—everybody there. I enjoyed working with everyone.

I think the reason for Hammer’s success is that they hit a happy time when people were wanting that type of film—thriller, science fiction, Gothic. I think they just happened to hit the right button at the right time. They certainly hit it right and certainly have become a milestone in the British film industry.

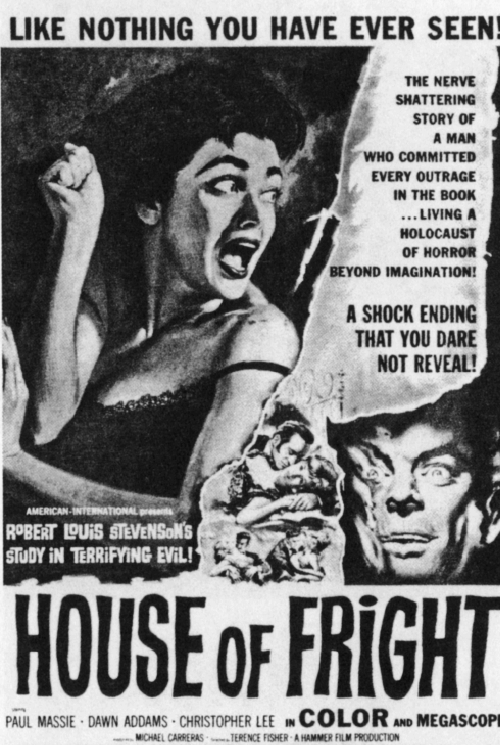

Released October 24, 1960 (U.K.), May 3, 1961 (U.S.); 88 minutes; Technicolor; Megascope; 7878 feet; a Hammer Film Production; released through Columbia (U.K.), American International (U.S.); filmed at Bray and Elstree Studios; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Michael Carreras; Associate Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay: Wolf Mankowitz, based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s novelette “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”; Director of Photography: Jack Asher; Music and Songs: Monty Norman and David Hencker; Music Supervisor: John Hollingsworth; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Eric Boyd-Perkins; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Production Manager: Clifford Parkes; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Continuity: Tilly Day; Sound: Jock May; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Hairdresser: Ivy Emmerton; Costume Designer: Mayo; Wardrobe: Molly Arbuthnot; Dances: Julie Mendez; Assistant Art Director: Don Mingaye; Casting: Dorothy Holloway; Stills: Tom Edwards; Assistant Director: John Peverall; Second Assistant: Hugh Marlow; Sound Editor: Archie Ludski; Masks: Margaret Robinson. U.S. title: House of Fright; U.K. Certificate: X.

Paul Massie (Jekyll/Hyde), Dawn Addams (Kitty), Christopher Lee (Paul Allen), David Kossoff (Litauer), Francis De Wolff (Inspector), Norma Marla (Maria), Joy Webster, Magda Miller (Sphinx Girls), Oliver Reed (Young Tough), William Kendall (Clubman), Pauline Shepherd (Girl in Gin Shop), Helen Goss (Nannie), Dennis Shaw (Hanger-on), Felix Felton (Gambler), Janine Faye (Jane), Percy Cartwright (Coroner), Joe Robinson (Corinthian), Joan Tyrill (Major Domo), Douglas Robinson (Boxer), Donald Tandy (Plainclothes Man), Frank Atkinson (Groom), Arthur Lovegrove (Cabby).

London, 1874. Dr. Henry Jekyll’s (Paul Massie) life is in tatters. His theories about man’s duality are ridiculed by his colleagues, and his wife, Kitty (Dawn Addams), is having a public affair with his “friend” Paul Allen (Christopher Lee). Ignored by his wife and ignoring warnings from his associate, Litauer (David Kossoff), Jekyll injects himself with a drug designed to free his “inner man.” Released from Jekyll’s moral restraints, “Mr. Hyde” (Massie) is younger, handsome, and beyond good and evil, living for his own gratification. At the Sphynx, a disorderly club, Hyde spots Kitty and Paul together, and ingratiates himself with Paul. Hyde pursues “his” wife sexually, but is rejected. In exchange for being introduced to London’s lower depths, Hyde takes over Paul’s considerable gambling debts, then gives Kitty the opportunity to “buy back” her lover.

The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll poster (courtesy of Fred Humphries and Colin Cowie).

When Kitty again refuses him, Hyde arranges a meeting between husband, wife, and lover at the Sphynx where he kills Paul with Maria’s (Norma Marla) boa constrictor, which she uses in her dance act. He then rapes Kitty, who afterwards falls to her death through a skylight. Hyde takes Maria to Jekyll’s home where, after “making love,” he strangles her, awakening as Henry. Hyde, to continue his mastery over Jekyll, kills a laborer and burns the corpse, explaining to the Inspector (Francis De Wolff) that Jekyll died after attempting to murder him. At the inquest, Jekyll is found guilty of all the murders and declared a suicide. As a smirking Hyde leaves the courtroom, Jekyll gains mastery and returns, aged and spent. He and Litauer exult in Hyde’s destruction, but both realize that Jekyll has destroyed himself.

The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll was Hammer’s biggest gamble during the company’s first round of horror remakes. Why? The familiar story was completely turned on its head, and although England’s greatest “monster” was in the cast, Christopher Lee did not play the monster. In fact, there is no monster. Earlier actors to play the dual role included John Barrymore, Fredric March, and Spencer Tracy. Hammer chose Paul Massie! Although the film contains little visual horror, its plot elements are morally repellent. And, earlier in 1960, Hammer’s comedy version of the same subject, The Ugly Duckling, was released. With all this against the film, it remains a fascinating failure that deserves credit for at least daring to be different.

Hammer was going head-to-head with not only a literary classic, but with three Hollywood icons. Their successor was the relatively unknown Paul Massie, who was actually quite a catch for Hammer after his brilliant debut in Orders to Kill (1958), for which he won the British Film Academy’s Most Promising Actor award. He followed this with good roles in Sapphire (1958) and Libel (1959). “I fairly jumped at the opportunity,” he was quoted in the film’s pressbook. “The role is an actor’s delight and runs the emotional gamut from top to bottom.” His performance has not received proper credit, perhaps due to the preconceived notion that he could not top his famous predecessors. Even the stuffy Films and Filming (December, 1960) allowed that “Massie’s study of dualism is quite passable.” Terence Fisher said in Cinefantastique that “Massie understood the role and felt it. There was not one redeeming character— it was an exercise, rightly or wrongly, in evil.”

Dr. Jekyll’s alter ego (Paul Massie) in The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll.

The movie’s one brilliant (or ludicrous) concept is that instead of becoming a snarling ape, Jekyll sheds twenty years—and his beard—to become Hyde, the charming seducer. While many approved of this novel twist, the “appearing/disappearing beard” is an annoyance.

Although Massie is fine as Jekyll/Hyde, Christopher Lee steals the film with a refreshing naturalness that adroitly reveals Paul Allen’s decadent charm. “The part was written for me,” he said in The Films of Christopher Lee. “I think it was one of the best performances I’ve given.” Making his Hammer debut was Oliver Reed, who recalled in Reed All About Me, “When I came out of the Army, I went to my uncle (Director Carol Reed), and he said to go into repertory if I wanted to be an actor. It was good advice, so I ignored it completely. I took my photos around, and got a bit in Jekyll.’’

The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll was the first association between Hammer and American International, who had been friendly rivals since 1957. Sam Arkoff, AIP head, told the authors in June, 1992, “We did some business with Hammer, and we could have done more, but we had our thing going. It just never occurred to us to do a co-production until The Vampire Lovers. AIP had an English connection, a producer named Nat Cohen. We met Jimmy Carreras through Nat at a Variety Club benefit. Jimmy was quite a guy! He and I became great friends. We never saw each other as rivals—the market was a big one with plenty for all.”

The Two Faces… was retitled for America as House of Fright.

James Carreras announced his intention to remake Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in The Kinematograph Weekly (March 12, 1959), signed Paul Massie on November 19, and had the cameras turning on November 23. “The subject,” Carreras said, “has been filmed before, but our script boys have come up with an astonishing new approach. This new concept is so brilliantly original, and yet so simple, that a lot of filmmakers will be kicking themselves silly that they never thought of the idea themselves.” “Our problem,” said Michael Carreras, “was that Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has already been filmed—and well-filmed, too. Wolf Mankowitz came up with a twist which virtually gives us a new story. As it is, we have a sex film rather than a horror picture.”

One of the film’s main characters was a python. Margaret Robinson told the authors (August, 1993) of her problems.

The actress playing the snake charmer couldn’t dance very well, so the woman who handled the snake had to dance with it in some shots, so I had to make a mask to disguise the two women. Since this was a last minute decision, I had to stay up all night. I also made a snake. Christopher Lee wasn’t too keen on snakes, so I had to make two—one to look alive, one to look dead. I went to a lot of trouble over these snakes—they were real beauties! Afterwards, I was with Bernard, Michael, and the snake charmer, and we compared the real snake to the models. Michael picked up the real snake, thinking it was a fake! Then—after all this—they decided not to use my snakes! Michael smiled and said, “Never mind, we’ll use them in another picture.”

Filming ended on January 22, 1960, with two weeks at Elstree due to construction at Bray. After an August 20 trade show at the Columbia, the film premiered at the Pavilion on October 7, and was released on the ABC circuit on October 24, to mixed reviews:

The London Times (October 10): “An ingenious, though repellent variation”; The Sunday Times (October 9): “Paul Massie does what he can to save something from a wreck alternately risible and nauseating”; The Observer (October 9): “A vulgar, intentionally foolish work”; The Spectator (October 14): “It has peculiarly horrid moral inversions”; The News Chronicle (October 7): “Its horrors are penny dreadful”; The Kinematograph Weekly (October 6): “Characterization bold, climax stern and spectacular”; Variety (October 19): “Terence Fisher’s direction is done effectively with few holds barred. The Victorian atmosphere is well put over”; The New York Herald Tribune (August 24, 1961): “A colorful, ingenious remake.”

Death of a scoundrel. Christopher Lee in The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll.

The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll was distributed in the U.S. by American International as House of Fright with few references to its origin in the ads. Surrounded by better horror movies like House of Usher and The Brides of Dracula, it sank without a trace, which is unfortunate.

Although it is difficult to defend many of its lapses, the picture deserves credit for finding a new way to film an old story.