Released August 14, 1961 (U.K.); 89 minutes; B & W; 7289 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a Columbia/BLC Release; filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Wolf Rilla; Producer: Maurice Cowan; Associate Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Falkland Carey, Philip King, based on their stage play; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Music: Douglas Gamley; Music Director: John Hollingsworth; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Albert Cox; Production Manager: Clifford Parkes; Camera: Len Harris; Continuity: Tilly Day; Sound: Jock May; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Hairdresser: Frieda Steiger; Wardrobe Mistress: Rosemary Burrows; Casting: Stuart Lyon; Stills: Tom Edwards; Assistant Director: John Peverall; 2nd Assistant Director: Dominic Fulford; Art Director: Don Mingaye; U.K. Certificate: U.

Dennis Price (Lt. Cmdr. Hardcastle), Liz Fraser (Daphne), Irene Handl (Edie Hardcastle), Graham Stark (Bligh), Vera Day (Shirley), Marjorie Rhodes (Ma Hornett), Cyril Smith (Mr. Hornett), John Meillon (Tufnell), Frankie Howerd (Organist), Miriam Karlin (Mrs. Lack), Arthur Howard (Vicar), Renee Houston (Mrs. Mottram), Brian Reece (Solicitor), Bobby Howes (Drunk), Harry Locke (Ticket Collector), William Mervyn (Captain), Marianne Stone (Woman), Diane Aubrey (Barmaid).

Hammer’s last military comedy, Watch It, Sailor!

Seaman Albert Tufnell (John Meillon) cannot decide between the joy of marrying Shirley Hornett (Vera Day) and the horror of having Mrs. Hornett (Marjorie Rhodes) as his mother-in-law. On his way to the church with Bligh (Graham Stark), their car breaks down, and when they finally arrive, the wedding party is gone. They rush to the Hornetts’ home, and after he receives a brutal tongue-lashing, a new date is set. But, this time Albert is left at the altar. It seems that he was born out of wedlock, and there is a question about his legal name, which Ma plans to use to keep Shirley single. The couple have other plans—they decide on a honeymoon first, and to marry later. They get as far as the train station when Ma catches up. The misunderstanding cleared up, they are now free to marry, but Shirley’s cousin Daphne (Liz Fraser) has run off with Bligh!

Watch It, Sailor! was Hammer’s fifth and last “service comedy.” Filmed for the domestic market, the previous four comedies were successful within the limits Hammer placed upon them and introduced their product to those not interested in horror. One of the company’s strengths was its ability to capitalize on a success in another medium. Watch It, Sailor!, a sequel to Sailor Beware, was written by Philip King and Falkland Carey, and had been a hit on the London stage. Hammer had considerable success with Up the Creek and its sequel, so another shot at a “service comedy” seemed right.

The production closed on March 1, 1961, completing a five week schedule, and it was released on August 14 to mostly negative reviews and little box office excitement. The Kinematograph Weekly (July 6): “Its humor, verbal rather than physical, produces a mere trickle of laughs”; and The Monthly Bulletin (July): “Slack direction and a flat-footed adaptation.” The “slack direction” was by Wolf Rilla, whose career spanned three decades and produced one classic—Village of the Damned (1960). Since the script was written by the authors of the hit play, it seems that the film’s failure was caused by Rilla’s inability to punch the humor across. The box office performance of Watch It, Sailor! must have been terrible, since Hammer waited ten years before filming another (intentional) comedy.

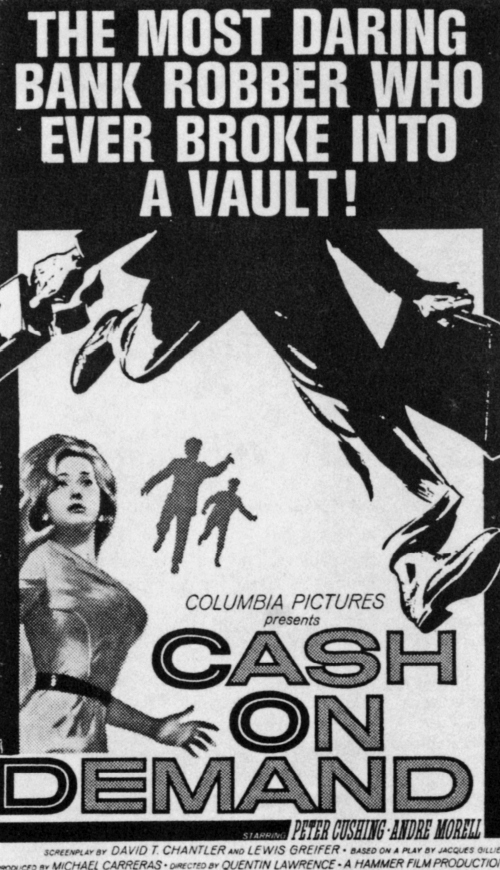

Cash on Demand

Released December 20, 1961 (U.S.), December 15, 1963 (U.K.); 84 minutes (U.S.), 66 minutes (U.K.), Copyright length 77 minutes; B & W; a Hammer-Woodpecker Production; a British Lion Release (U.K.), a Columbia Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios, England; Director: Quentin Lawrence; Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: David T. Chantler, Lewis Greifer, based on the play The Gold Inside by Jacques Gillies; Music: Wilfrid Josephs; Music Supervisor: John Hollingsworth; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Eric Boyd-Perkins; Production Manager: Clifford Parkes; Sound Recordist: Jock May; Sound Editor: Alban Streeter; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Assistant Director: John Peverall; Continuity: Tilly Day; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Wardrobe Supervisor: Molly Arbuthnot; Wardrobe Mistress: Rosemary Burrows; Hairstyles: Frieda Steiger; Casting Director: Stuart Lyons; Assistant Director: John Peverall; U.K. Certificate: A.

Peter Cushing (Fordyce), Andre Morell (Hepburn), Richard Vernon (Pearson), Barry Lowe (Harvill), Norman Bird (Sanderson), Edith Sharpe (Miss Pringle), Charles Morgan (Collins), Kevin Stoney (Det. Mason), Alan Haywood (Kane), Lois Daine (Sally), Vera Cook (Mrs. Fordyce), Gareth Tandy (Tommy), Fred Stone (Window Cleaner).

The Christmas spirit infecting the staff of a provincial bank has eluded its prissy, petty manager, Mr. Fordyce (Peter Cushing), who is universally disliked. After giving Pearson (Richard Vernon) an unjustified reprimand, Fordyce is unsettled by the arrival of an insurance investigator, the intimidating Colonel Hepburn (Andre Morell). The staff fails to check “Hepburn’s” credentials—he is actually a bank robber. The “Colonel,” through a phone call from Mrs. Fordyce, convinces her husband that unless he complies, his family will be killed. Hepburn is as interested in Fordyce’s miserable personality as he is in the vault, and offers him hints on how to improve it. To atone for his misdemeanors, Pearson makes a check-up call to London, but it is delayed.

Hepburn and Fordyce descend to the vault with the “Colonel’s” empty luggage and, after a few close calls, emerge with £93,000. After warning Fordyce that his family is still in danger, Hepburn—with a cheery word for all—drives off. Pearson’s call is finally connected, and he learns of the “Colonel’s” deception. Unaware of the consequences, Pearson calls the police, then confronts Fordyce with his suspicions. Fordyce begs him to tell the police a msitake was made, explaining that his family is in danger. Pearson and the staff support the lie, but Detective Mason (Kevin Stoney) has already apprehended Hepburn.

Unnerved by Hepburn’s return, Fordyce foolishly implicates himself in the robbery, but the “Colonel”—for reasons of his own—admits he faked Mrs. Fordyce’s phone call with a tape recording. Freed from suspicion, grateful for his staff’s loyalty, and ashamed of his conduct, Fordyce is a changed man.

Cash on Demand was one of Hammer’s best films, and an atypical sixties production that was reminiscent of the company’s productions a decade earlier. Based on Jacques Gillies’ play The Gold Inside (which aired on the London ATV network on September 24, 1960), the Hammer-Woodpecker production began on April 4, 1961. “This was an unusual picture for Hammer to have made,” Len Harris told the authors (December, 1993). “It was basically a two character drama. I remember thinking as we were doing it that the picture would have worked just as well if Peter and Andre had switched roles. How many actors are that versatile? Both men were kind, considerate, and professional—always a delight to work with. Hammer got Quentin Lawrence to direct because of his television experience. He was very quick and efficient. I was actually director of photography for a few days when Arthur Grant became ill, and I stood in for him. We could do things like that in those days—the unions weren’t quite so fussy! I did the robbery scene.”

Colonel Hepburn (Andre Morell) keeps up the pressure as he waits for Fordyce (Peter Cushing) to open the bank vault in Cash on Demand.

Peter Cushing was grateful for the break from horror movies, telling interviewer Patricia Lewis, “I was sort of carried along with the cycle. It was wonderful to work steadily on from one film to the next, but then a few weeks ago, I realized that most were X certificate.” He described Fordyce as “a martinet, a man who lacks charity and warmth. In his office, as a manager of a bank, he is stern, forbidding. He derives satisfaction from holding the threat of dismissal over his staff. This, then, is the man who suddenly finds himself the center of a drama that rocks him to the core and alters his life.” The role was one of Cushing’s best, and he is alternatingly hateful, pathetic, admirable, and funny. Andre Morell is at least his equal, and they combined to give the two best performances in any one Hammer film.

Hammer’s version of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

Production ended on April 16, 1961, but the film’s English distribution was unaccountably delayed. Columbia released Cash on Demand in America on December 20, 1961, but the British premiere came two years later. Reviews were, justifiably, positive. The Monthly Film Bulletin (December, 1963): “A neat and quite freshly conceived robbery thriller”; The Kinematograph Weekly (November 19, 1963): “Sound acting by all, especially by the two principals”; and The New York Times (May 17, 1962): “Neat and unpretentious.” Why Hammer stopped making films like this is a mystery, as is the cause of its seeming disappearance. Not only is the film seldom shown on television, it often goes unmentioned in film guides. Cash on Demand is an example of the excellence the company was capable of, but seldom achieved after the fifties. With its drama, suspense, humor, and insight, Cash on Demand is everything one could want from a movie. It is Hammer’s version of A Christmas Carol, and a very good one at that.

Released May 20, 1963 (U.K.), July 7, 1965 (U.S.); 87 minutes (U.K.), 77 minutes (U.S.); B & W; Hammerscope; 7838 feet; a Hammer-Swallow Production; filmed at Bray Studios; Released by British Lion (U.K.), Columbia (U.S.); Director: Joseph Losey; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Associate Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay: Evan Jones, based on H.L. Lawrence’s novel The Children of Light; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Reginald Mills; Music: James Bernard; Music Director: John Hollingsworth; Song “Black Leather Rock” by Evan Jones and James Bernard; Sound: Jock May; Production Assistant: Richard MacDonald; Assistant Director: John Peverall; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Costumes: Molly Arbuthnot; Continuity: Pamela Davies; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Hairstyles: Frieda Steiger; Production Manager: Don Weeks; Casting: Stuart Lyons; Sculptures: Elizabeth Frink; U.S. Title: These Are the Damned; U.K. Certificate: X.

Poster from The Damned (courtesy of Fred Humphries and Colin Cowie).

Macdonald Carey (Simon Wells), Shirley Ann Field (Joan), Viveca Lindfors (Freya), Oliver Reed (King), Alexander Knox (Bernard), Walter Gotell (Major Holland), James Villiers (Captain Gregory), Kenneth Cope (Sid), Thomas Kempinski (Ted), Brian Oulton (Mr. Dingle), Barbara Everest (Miss Lamont), Alan McClelland (Mr. Stuart), James Maxwell (Mr. Talbot), Rachel Clay (Victoria), Caroline Sheldon (Elizabeth), Rebecca Dignam (Anne), Siobhan Taylor (Mary), Nicholas Clay (Richard), Kit Williams (Henry), Christopher Witty (Wilham), David Palmer (George), John Thompson (Charles); David Gregory, Anthony Valentine, Larry Martyn, Leon Garcia, Jeremy Phillips (Teddy Boys).

Simon Wells (Macdonald Carey), a wealthy American on holiday, is picked up by Joan (Shirley Ann Field), an attractive decoy for a “teddy boy” gang led by King (Oliver Reed), her psychotic brother. Simon is beaten and robbed, and is found by security officers from a secret military installation. Taken to a hotel to recuperate, Simon meets Bernard (Alexander Knox), head of the project, and his lover, Freya (Viveca Lindfors). Later, Joan approaches Simon on his boat and tries to justify her behavior when her incestuously jealous brother arrives. She leaves with Simon, but when he makes a clumsy pass at her, asks to be put ashore. They break into Freya’s cottage near the installation, make love, and leave before King arrives.

Inside the installation, Bernard addresses, via television, nine strange children who think they are being prepared for a space journey, but are part of a radiation experiment. They are immune to fallout, but can poison by their touch. The gang chases Simon and Joan into the sea where they—along with King—are rescued by Victoria (Rachel Clay) and Henry (Kit Williams), two of the children. Bernard tries to separate the children and adults, but it is too late—they are already poisoned. The adults misinterpret Bernard’s actions, and try to escape with the children. King and Henry speed off in Freya’s car, pursued by a helicopter. King, dying from radiation, drives off a bridge. Bernard releases Simon and Joan, who die in the boat, then shoots Freya, who knows too much.

Macdonald Carey is helpless to prevent death by radiation in The Damned.

American director Joseph Losey, “blacklisted” during the Communist scare, relocated in England. He was given A Man on the Beach, a Hammer short, as one of his first assignments. Pleased with the result, Hammer offered him The Criminal, to star Stanley Baker, but Losey turned it down. Still keen on having Losey direct a feature, Anthony Hinds used director Carl Foreman (himself blacklisted) as a go-between. Losey, in Michael Ciment’s Conversations with Losey, said, “When we got into trouble on the picture, Tony Hinds just disappeared and was nowhere to be found. And the man who rescued the situation for me then was Michael Carreras. I must say that Michael, ever since, has been trying to get me to do another picture with him, but he always gives me things that have so much overt violence in them I just can’t consider them seriously.”

Based on H.L. Lawrence’s novel The Children of Light, The Damned began filming at Bray on May 8, 1961. The Kinematograph Weekly (June 15) visited the set and found an enthusiastic Oliver Reed about to make a record for Decca called Lonely for a Girl. Macdonald Carey had found success on American television, and The Damned was to be his British launching pad, but the rocket never took off due to the film’s problem finding a release. Losey was very interested in the subject of radiation, but had reservations about two of his stars. He said in Conversations with Losey that he was forced to use Shirley Ann Field because she had just appeared with Laurence Olivier in The Entertainer (1960). Losey liked Oliver Reed personally, but felt the actor had “no training at all, and he already had a certain arrogance, so he wasn’t easy.” He was, however, honest enough to admit that Reed helped the movie. The production ended on June 22, 1961, and what followed was more convoluted than the film’s plot. Despite an up-to-the-minute subject and a “name” director and stars, The Damned sat on the shelf for almost two years. When it finally premiered at the Pavilion on May 30, 1963, it was in support of Maniac, and would have gone unnoticed if not for its director. Since finishing The Damned, Losey had become a darling of the critics due to The Servant (1963), and his films were now the object of “serious study.” Much was made of the movie’s belated release caused by BLC’s confusion over how to market what they thought would be a conventional “Hammer horror.”

The London Times (May 30) commented, “Mr. Joseph Losey is one of the most intelligent, ambitious, and consistently exciting filmmakers now working in the country. It would be a thousand pities were his latest film, after 18 months on the shelf, to go out unremarked at the lower half of a ‘double X’ all horror programme.” In agreement were The Evening News (May 23): “It carries the imprint of a master film maker”; The Observer (May 12): “What is Hammer-Columbia so reluctant and coy about?”; and The Telegraph (May 26): “Brilliant, flawed.” The Kinematograph Weekly (March 21) singled out Oliver Reed’s King as a “nasty piece of work.” Yet, despite the positive reviews, The Damned was denied an American release. Incredibly, it won first prize at The Trieste Science Fiction Festival in July, 1964; and even more incredibly, it took another year for the film to open in New York as These Are the Damned on July 7, 1965. Variety (July 14) called it “a strange but fascinating film”; and The New York Times (July 8) found it “Orwellian.”

The Damned paid a price for its twisted history. Due to cuts for two double features (Genghis Khan in the U.S.), the running time dropped from 100 to 77 minutes. If 23 minutes were removed from Citizen Kane, the result would be incomprehensible, too, so it is unfair to carp about vagueness and plot holes. What’s left of major interest is Arthur Grant’s crisp black and white photography and an outstanding job by the underappreciated Oliver Reed, who got fifth billing. There is enough left of The Damned, even with missing a quarter of its running time, to make it one of the decade’s most interesting science fiction films.

Released August 13, 1962 (U.K.), July, 1962 (U.S.); 84 minutes (U.K.), 87 minutes (U.S.); Technicolor (U.K.), Eastman Color (U.S.); 7584 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a British Lion Release (U.K.), a Columbia Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: John Gilling; Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: John Gilling, John Hunter, from Jimmy Sangster’s story; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Music Composed by: Gary Hughes; Musical Director: John Hollingsworth; Production Designer: Bernard Robinson; Production Manager: Clifford Parkes; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Editor: Eric Boyd-Perkins; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Special Effects: Les Bowie; Horse Master/Master at Arms: Bob Simmons; Camera Operator: Len Harris; Assistant Director: John Peverall; Sound Recordist: Jock May; Sound Editor: Alfred Cox; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Costumes: Molly Arbuthnot; Continuity: Tilly Day; Wardrobe Mistress: Rosemary Burrows; Hair Stylist: Frieda Steiger; Casting: Stuart Lyons; U.K. Certificate: U.

Kerwin Mathews (Jonathan), Glenn Corbett (Henry), Christopher Lee (LaRoche), Marla Landi (Bess), Oliver Reed (Brocaire), Andrew Keir (Jason), Peter Arne (Hench), Michael Ripper (Mac), Jack Stewart (Mason), David Lodge (Smith), Marie Devereux (Maggie), Diane Aubrey (Margaret), Jerold Wells (Commandant), Dennis Waterman (Timothy), Lorraine Clewes (Martha), John Roden (Settler), Desmond Llewelyn (Blackthorne), Keith Pyott (Silas), Richard Bennett (Seymour), Michael Mulcaster (Martin), Denis Shaw (Silver), Michael Peake (Kemp), John Colin (Lance), Don Levy (Carlos), John Bennett (Guard), Ronald Blackman (Pugh).

Jonathan Standing (Kerwin Mathews), the son of the leader of a Caribbean Huguenot settlement, is banished to a penal colony for breaking the strict moral code established by the elders. Despite the pleas of his friend Henry (Glenn Corbett) and his sister Bess (Marla Landi), Jonathan’s father Jason (Andrew Keir) remains unmoved. Jonathan escapes from the prison and is taken in by a band of pirates led by LaRoche (Christopher Lee), who rules in absolute control despite a withered arm and sightless eye. He is convinced that the colony has a cache of gold and makes a “deal” with Jonathan. If he is taken to the gold—which Jonathan denies the existence of—LaRoche will restore democracy to the settlement.

Kerwin Mathews (left) and Christopher Lee duel to the death in The Pirates of Blood River.

LaRoche’s true nature is revealed when he orders Hench (Peter Arne) to destroy a helpless family. Soon in charge of the settlement, LaRoche threatens to execute one person per day until the gold is procured. His men are now barely under control, as Hench kills Brocaire (Oliver Reed) in an animalistic fight over Bess. LaRoche discovers that a huge statue of the colony’s founder is solid gold and takes it—with Jason and Jonathan as hostages—to the ship. Led by Henry, the islanders decimate the pirates through clever ambushes. Mac (Michael Ripper) leads a mutiny against LaRoche’s faltering command and, with the statue lashed to a raft, attempts to reach the ship with the remaining crew. Jonathan defeats LaRoche in a duel as the sinking raft is attacked by a school of piranha, killing both the pirates and Jason Standing.

Hammer’s swashbuckler was a big hit at kiddie matinees.

After his exhilarating performance in The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (1958), Kerwin Mathews was the screen’s reigning swashbuckler. He recalled for the authors (January, 1992),

I was under contract to Columbia, and they had just OK’d my living in London. I had just settled in when Hammer called. I always enjoyed working in England. The studios were first class and all the people involved were a bit more gentle than their American counterparts. John Gilling and Michael Carreras were very organized professionals and were most thoughtful of the actors and crew. Gilling had his hands full making a difficult film come in on schedule in English weather, but he was super-efficient and good for me. The film was physical and rough—it couldn’t have been otherwise. One morning I had to do a scene in a swamp that had turned to quicksand. I had one of the frights of my life! I was so proud that Andrew Keir was playing my father. I thought he was such a good actor. Also, I was in awe of Oliver Reed and his famous relative, Sir Carol. [Sir Carol Reed was one of the great directors with pictures like Odd Man Out (1947), The Fallen Idol (1948), The Third Man (1949), and Oliver! (1968) to his credit.] Oliver was such a special man physically, and a fine actor. I always watched him work with envy, wishing I could be that way sometimes. He was a real pro, too. I had worked with British actors primarily in Sinbad and The Three Worlds of Gulliver (1960), so my mid–Atlantic Wisconsin college bred accent seemed to work. This was always an important consideration. Note: “Yonder lies de cassle of my faddah!” I really liked going to Bray each day and doing what I knew how to do best in a very nice place with nice people.

Originally titled Blood River, the film started production on July 3, 1961, and concluded on August 31 with location work at Black Park. James Carreras left for New York on January 13, 1962, to meet with Columbia executives. “It struck me,” he said in The Sunday Times, “there was a lot of business to pick up around the kids’ holiday period. Nobody had touched it except, of course, Disney, who had the field to himself.” As a result, The Pirates of Blood River went out with the Columbia-made Mysterious Island and became the top earning double feature in the U.K. for 1962. Following a May 5 trade show at the Columbia Theatre, the pair premiered at the Pavilion on July 13 and went into general release a month later. Oddly, the films alternated playing “top.” The Kinematograph Weekly (August 2, 1962) reported: “Whichever way the programme is arranged, it offers darn good value for the money. And don’t forget, both films carry U certificates. What a chance for Mom to get rid of the kids!” By early September, the films were racking up record-breaking grosses on the ABC circuit, with many cinemas reporting receipts 50 percent above normal. Despite the film’s popularity, many reviews were condescending. The Monthly Bulletin (June, 1962): “Stodgy, two-dimensional costume piece”; Variety (July 25): “Satisfactory adventure meller”; and The Kinematograph Weekly (May 10): “Thrilling story, robust characterization, hectic highlights.”

The Pirates of Blood River was the first of Hammer’s three unrelated pirate movies and helped to solidify the company’s move away from Gothic horror in the early sixties. The cast is one of the best Hammer assembled, with the exception of Columbia throw-in Glenn Corbett. He is more than balanced by Christopher Lee’s outstanding performance and by Michael Ripper in an all too rare featured role. This is one of Hammer’s most satisfactory all-around films, and is an example of low budget filmmaking at its best.

Released June 25, 1962 (U.K.), June 13, 1962 (U.S.); 82 minutes; Technicolor (U.K.), Eastman Color (U.S.); 7380 feet; a Hammer-Major Production; a Rank Organization Release (U.K.), a Universal-International Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Peter Graham Scott; Producer: John Temple-Smith; Screenplay: John Elder; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Music composed by: Don Banks; Musical Director: Philip Martel; Production Designer: Bernard Robinson; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Editor: Eric Boyd-Perkins; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Special Effects: Les Bowie; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Assistant Director: John Pervall; Hair Stylist: Frieda Steiger; Wardrobe: Molly Arbuthnot; Additional Dialogue: Barbara S. Harper; Second Assistant Director: Peter Medak; Sound: Jock May; U.S. Title: Night Creatures; U.K. Certificate: A.

Peter Cushing (Dr. Blyss/Capt. Clegg), Yvonne Romain (Imogene), Patrick Allen (Capt. Collier), Oliver Reed (Harry Crabtree), Michael Ripper (Mipps), Martin Benson (Rash), David Lodge (Bosun), Derek Francis (Squire), Daphne Anderson (Mrs. Rash), Milton Reid (Mulatto), Jack MacGowran (Frightened Man), Peter Halliday (Sailor Jack Pott), Terry Scully (Sailor Dick Tate), Sydney Bromley (Tom Ketch), Rupert Osborne (Gerry), Gordon Rollings (Wurzel), Bob Head (Peg-Leg), Colin Douglas (Pirate Bosun).

1776. The High Seas. A mulatto pirate (Milton Reid) is placed on a desert island—his ears and tongue mutilated—for attacking the pregnant wife of Captain Clegg.

The years pass. Captain Collier (Patrick Allen) is investigating the smuggling of French brandy into the English village of Dymchurch—a town haunted by “Marsh Phantoms” and the grave of Captain Clegg. The vicar, Dr. Blyss (Peter Cushing), while polite, is unwilling to aid Collier’s search. While dining with the Captain, the Squire (Derek Francis), and his son Harry (Oliver Reed), Blyss is attacked by Collier’s “ferret”—the mulatto. Most of the town, including Rash (Martin Benson), the innkeeper, and the coffin maker Mipps (Michael Ripper) are part of the smuggling team headed by Blyss. To keep the curious off the moor, they dress like living skeletons—the marsh phantoms.

Harry and Imogene (Yvonne Romain), Rash’s ward, want to marry but are stymied by their different social positions. When Rash drunkenly molests her, she learns that her real father was Clegg. She runs to Blyss, who confirms Rash’s tale. Enraged, Harry confronts Rash who reveals him to Collier as “the scarecrow”—a lookout for the smugglers. Harry escapes, and he and Imogene are married by Blyss. Collier deduces that Blyss is actually Clegg, and exposes the “dead” pirate before the congregation. They rally behind the man who saved them from poverty, as Clegg explains that, after his botched hanging, he became a “new man.” He and Mipps escape during the confusion and are attacked by the mulatto with a harpoon, and Clegg dies protecting his friend. As Clegg is buried for a second time, Collier lowers his head respectfully.

Patrick Allen (left) and Peter Cushing break for tea on the set of Captain Clegg.

Despite Hammer’s failure to mention it in the credits, Captain Clegg was based on Russell Thorndyke’s 1915 novel Dr. Syn, which inspired a 1937 film starring George Arliss. After not hearing from the pirate-priest for 25 years, suddenly two films appeared in 1962 when Hammer decided, along with Walt Disney, to dust off the property. The Kinematograph Weekly (September 7, 1961) announced that Hammer planned to begin production of Dr. Syn on September 18. Meanwhile, Disney planned to shoot Dr. Syn—Alias the Scarecrow as an American television film to be released theatrically elsewhere. Disney had been quicker to secure the copyright than Hammer, causing the company to change the character’s name (if not his intentions). No other changes were required, since Disney had only copyrighted the title.

Hammer more or less followed the plot of the 1937 film, but with two major changes—splitting the parson/scarecrow into two characters, and having the parson killed off. Production was pushed back to September 25, concluding on November 6, with location work at Black Park, Denham Village, and a deconsecrated church near Bray.

Peter Cushing (center) is coached by the Vicar of Bray while director Peter Graham Scott looks on in Captain Clegg (photo courtesy of Tim Murphy).

Captain Clegg provided Michael Ripper with, perhaps, his best role for Hammer, as he was given the chance to play a “real” character instead of a walk-on far beneath his ability. “I was very lucky,” he told the authors (April, 1993).

I was a good stage actor and got my first job in films in quota pictures. I was “over the top” a bit due to my stage background, but in the quota pictures it didn’t really matter. In one early Hammer picture, I asked the producer how I was, and he said—“terrible”—but they couldn’t cut around me. I thought that would be the end of me. But, I stuck around. I learned the technique of not overacting. Nobody believes you when you’re over the top. One of the main reasons I was in so many Hammer films was my friendship with Tony Hinds. He is a very quiet man—not at all like a film producer! He wrote a great many scripts, too, as John Elder, and, I suspect, he always wrote a part for me. One of my favorites was Captain Clegg—a great part, a great story, and a great cast. I always enjoyed Peter Cushing, of course, and Oliver Reed was a lot of fun, too. It’s hard to pick my favorite Hammer film—it seems like I was in all of them!

Len Harris had, oddly, also worked on the 1937 version and recalled (December, 1993),

The last scene we shot was the attack on Dr. Syn with the harpoon. In those days, a star like George Arliss could get away with murder! He simply refused to work after 4:30 and would simply say, “Thank you, gentlemen,” and leave. We were running late on this final shot and he just got up, bid us good day, and left! Strangely enough, on Captain Clegg, the only scene we had to be late on was—of course—the harpoon scene. Peter Cushing, however, stayed until the shot was finished!

Captain Clegg was released, paired with The Phantom of the Opera, on June 25, 1962, to generally favorable reviews. The London Times (June 28): “An almost jolly story of smugglers and king’s men”; The New York Post (August 23): “Don’t sell this thriller short”; The New York Daily News (August 23): “Executed as if a big spectacle was in the making”; Variety (May 5): “The Hammer imprimatur has come to certify solid values, and there’s no mystery why these films rate audience allegiance”; Films and Filming (July): “A rattling good piece of comic book adventure”; The Observer (June 10): “Sickening makeup effects”; and The Monthly Bulletin (July): “The script is feeble, the acting uninspired.”

Hammer’s exciting pirate adventure Captain Clegg was, for American audiences, disguised as a horror movie, with the title Night Creatures.

Captain Clegg is the best of the company’s period adventures and provided Peter Cushing with one of his greatest roles. The film solidified James Carreras’ stand that Hammer had no commitment to any specific genre, and Captain Clegg is the type of picture Hammer should have made more of.

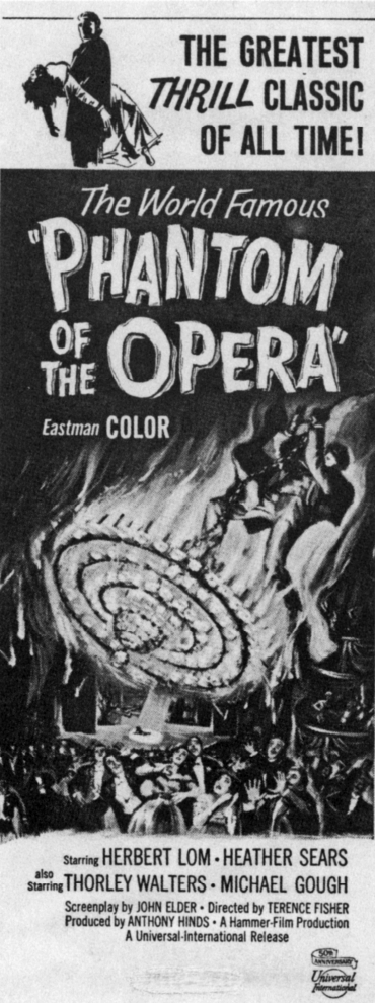

Released June 25, 1962 (U.K.), August 15, 1962 (U.S.); 84 minutes (U.K.), 94 minutes (U.S. Television); Technicolor (U.K.), Eastman Color (U.S.); 7560 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a Rank Organization Release (U.K.), a Universal Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios, England; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Anthony Hinds; Associate Producer: Basil Keys; Screenplay: John Elder, based on the story by Gaston Leroux; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Art Directors: Bernard Robinson, Don Mingaye; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Alfred Cox; Music Composed and Conducted by: Edwin Astley; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Production Manager: Clifford Parkes; Costumes: Molly Arbuthnot; Camera: Len Harris; 1st Assistant Director: John Peverall; 2nd Assistant Director: Peter Medac; Continuity: Tilly Day; Sound: Jock May; Hairdresser: Frieda Steiger; Wardrobe Mistress: Rosemary Burrows; Stills Camera: Tom Edwards; Sound Editor: James Groom; Sound Recordist: Jock May; Opera Scenes Staged by: Dennis Maunder; U.K. Certificate: A.

Herbert Lom (The Phantom/Petrie), Edward de Souza (Harry Hunter), Heather Sears (Christine Charles), Michael Gough (Lord Ambrose D’Arcy), Thorley Walters (Lattimer), Ian Wilson (Dwarf), Martin Miller (Rossi), John Harvey (Sgt. Vickers), Miles Malleson (Philosophical Cabby), Marne Maitland (Xavier), Michael Ripper (Long Faced Cabby), Patrick Troughton (Rat Catcher), Renee Houston (Mrs. Tucker), Sonya Cordeau (Yvonne), Liane Aukin (Maria), Leila Forde (Teresa), Geoff L’Oise (Frenchman), Miriam Karlin (Charwoman), Harold Goodwin (Bill), Keith Pyott (Weaver). Cast for U.S. Television added footage: Liam Redmond (Police Inspector), John Maddison (Police Inspector).

Lord Ambrose D’Arcy’s (Michael Gough) opera, Joan of Arc, is plagued by vandalism and murder, causing Maria (Liane Aukin), the lead singer, to resign. Director Harry Hunter (Edward de Souza) and Lattimer (Thorley Walters), the theatre manager, audition Christine (Heather Sears), and D’Arcy, captivated by her beauty, invites her to dinner to “discuss the role.” In her dressing room, a voice warns her of D’Arcy’s evil intentions. That night, after Harry “rescues” her, he and Christine return to investigate the voice. After the theatre rat catcher (Patrick Troughton) is murdered by a dwarf (Ian Wilson), Christine glimpses a masked man in black—the Phantom (Herbert Lom).

Herbert Lom joins Lon Chaney and Claude Rains as The Phantom.

Harry learns from a chance discovery of old sheet music of a Professor Petrie, a struggling composer who was swindled out of his music by D’Arcy. While attempting to destroy the stolen scores at a print shop, Petrie was severely burned but, aided by the dwarf, found refuge beneath the Opera. Christine is abducted by the dwarf and taken to Petrie’s chambers, where she is soon traced by Harry. Petrie tells his sad story and begs to be allowed to instruct Christine. Moved by his sincerity, the couple agrees.

Joan of Arc is restaged with Christine in the lead. At the premiere, Petrie confronts D’Arcy in his office, and Lord Ambrose rips off the mask. Horrified, D’Arcy runs out into the night. While Petrie weeps at Christine’s beautiful singing, the dwarf is chased through the rafters by a stagehand. As he leaps onto a chandelier, the rope snaps, sending it hurling toward Christine. Tearing away his mask, Petrie leaps onto the stage and pushes Christine to safety, sacrificing his life for hers.

The Phantom of the Opera, filmed by Universal in 1925 (Lon Chaney) and 1943 (Claude Rains) was re-made by Hammer as a result of an August, 1958, agreement with Universal International. Filming began on November 21, 1961, after a false start involving—Cary Grant! Anthony Hinds recalled (Fangoria 74), “Cary Grant came to us and said he wanted to make a horror film. The only thing we could think of was Phantom of the Opera. I knew he’d never make it, but he was insistent, so I wrote the thing for him.” After Hinds was proven correct, Herbert Lom—rather than Peter Cushing or Christopher Lee—was signed.

“Herbert Lom was a late choice for the role,” Len Harris told the authors (December, 1993), “but made the most of it. A lot of actors would have been unnerved, but he was unaffected by it all. Lom was excellent and gave something to the role that Cushing might not have. Like most Hammer stars, he was a real gentleman—and also quite a practical joker!”

Unlike Universal’s 1943 version, which borrowed music from Tchaikovsky and Chopin, Hammer’s Edwin Astley composed an original opera with Heather Sears convincingly dubbed by Pat Clark. Although most of the film was shot at Bray and Oakley Court, two weeks were spent at the Wimbledon Theatre. Len Harris recalled, “The theatre was much smaller than you’d think, and Terence Fisher was at his wit’s end to give it some size. We only used a few extras in costume to fill the seats and kept moving them around, changing hats and coats, to make it look like an army.” Another problem centered around the Phantom’s mask. “They had contracted a professional mask maker,” said Roy Ashton (Fangoria 35), “who turned out many super designs—none of which they were satisfied with. My suggestion was that this chap would have picked up a discarded prop to hide his disfigurement.” Hammer finally saw it his way after filming began with Lom maskless.

Michael Gough gets the shock of his life in The Phantom of the Opera.

The Phantom of the Opera concluded on January 26, 1962, after which Bray was shut down for five months for much needed maintenance. On May 17, Rank announced that they would premiere The Phantom of the Opera and Captain Clegg at the Leicester Square on June 7—a move applauded by The Kinematograph Weekly as a “generous value for the money.” The double feature went into general release throughout Britain on June 25. Inexplicably, the box office receipts were a major disappointment, with reviewers sharply divided. The Kinematograph Weekly (May 31, 1962): “The picture reinforces the emotional and musical aspect, but not at the expense of Grand Guignol thrills”; The Observer (June): “A very tame remake of the famous original”; Cue (August 25): “A pretty fair thriller”; The New York Post (August 23): “Eye filling”; The New York Times (August 23): “Ornate and pretty dull”; Time (August 31): “Ho-ho-horror”; and The London Times (June 8): “The frisson of real, genuine fear is absent.”

Perhaps the most harsh criticism came from Terence Fisher. “The weakness of The Phantom of the Opera is that its realism isn’t really justified,” he said (Cinefantastique, Vol. 4, No. 3). “There is no complexity to the Phantom’s actions; the character is never very close to us, and remains superficial.” Fisher, perhaps, was being a bit hard on himself. The film’s major fault is that it is not really a horror movie, and the few attempts at shock and gore seem out of place. Herbert Lom plays the Phantom for sympathy, and succeeds on a level that few Hammer “monsters” achieved. Heather Sears, who was awarded by the British Academy and the New York Film Critics for The Story of Esther Costello (1957), was both touching and beautiful, and rates among the best of all Hammer heroines. With the Phantom as a victim rather than a villain, there is only the sneering Michael Gough to hate, and he is more than up to the job.

A well intentioned failure.

Although finding financial success with The Curse of Frankenstein and other horrors, Hammer had yet to find “respectability”; and this remake of a Hollywood icon seemed to be the perfect vehicle. Unfortunately, despite many positives, The Phantom of the Opera cannot rate with its two more famous predecessors, and what could have been a major breakthrough for Hammer proved to be a minor disaster. The film was a turning point for the company, and could be used to mark the end of Hammer’s best period. But, the movie failed with dignity, and like the Phantom, it deserves our sympathy.