Released October 27, 1965 (U.S.), November 7, 1965 (U.K.); 93 minutes; B & W; a Hammer–7 Arts Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Studios, Elstree, England; Director: Seth Holt; Producer, Screenplay: Jimmy Sangster; Executive Producer: Anthony Hinds; Based on the novel by Evelyn Piper; Director of Photography: Harry Waxman, B.S.C.; Music: Richard Rodney Bennett; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Production Design: Edward Carrick; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Production Manager: George Fowler; Editor: Tom Simpson; Assistant Director: Christopher Dryhurst; Camera: Kevin Pike; Sound Recordist: Norman Coggs; Sound Editor: Charles Crafford; Continuity: Renee Glynn; Makeup: Tom Smith; Hairstylist: A.G. Scott; Wardrobe Consultant: Rosemary Burrows; Wardrobe Mistress: Mary Gibson; Recording Supervisor: A.W. Lumkin; U.K. Certificate: A.

Bette Davis (Nanny), Wendy Craig (Virgie Fane), Jill Bennett (Penelope), James Villiers (Bill Fane), William Dix (Joey), Pamela Franklin (Bobby), Jack Watling (Dr. Medman), Maurice Denham (Dr. Beamaster), Alfred Burke (Dr. Wills), Nora Gordon (Mrs. Griggs), Sandra Power (Sarah), Harry Fowler (Milkman), Angharad Aubrey (Susy).

In their fashionable London apartment, Bill and Virgie Fane (James Villiers and Wendy Craig) are preparing for the return of their ten-year-old Joey Fane (William Dix), who was accused of drowning his own baby sister Susy and has spent the last two years in an institution for psychologically disturbed children. Virgie confides to her trusted Nanny (Bette Davis) that she is frightened of the boy and does not feel that she can cope with him after what he has done. When Bill and Nanny drive to the school to pick up Joey, Dr. Beamaster (Maurice Denham) admits that Joey may still have certain psychological problems.

At home, Joey refuses to stay in a bedroom redecorated by Nanny and to eat food prepared by her. Suffering from food poisoning, Virgie is rushed to the hospital while Nanny claims to have found a bottle of potent medicine hidden under Joey’s pillow. Joey denies trying to poison his mother, and refuses to stay alone in the apartment with Nanny. Penelope (Jill Bennett), Virgie’s sister, is sent for. Bobbie (Pamela Franklin), a teenage friend of Joey’s, sneaks into the apartment and Joey tells her it was Nanny who poisoned Virgie and left the bottle in his bed. Penelope, who suffers from a weak heart, falls asleep in a chair and is wakened by Joey, dripping wet from his bath, who accuses Nanny of trying to drown him. The shock of Joey’s accusation causes Penelope to have a mild attack, and Nanny helps her into bed. Joey goes to Bobbie’s room and tells her that Susy died due to Nanny’s neglect.

Penelope later catches Nanny lurking suspiciously outside Joey’s door, and suffers a heart attack while struggling with the older woman. As Penelope dies, Nanny talks to her about the day Susy drowned. That was the day that Nanny got a call from a doctor concerning her own grown daughter Janet, who was given away at six months. In Janet’s slum apartment, Nanny found her dead after an abortion. Returning home to the Fanes in a dazed condition, Nanny neglected Susy, who toppled into the bathtub and drowned.

The disturbed Nanny forces her way into Joey’s room, knocks the boy unconscious and places him in the bathtub. Holding Joey’s head under the water, Nanny suddenly sees Susy’s body in the water and, in a moment of lucidity, realizes the horror of what she has done. Pulled out of the tub by Nanny, Joey wrestles out of her grasp and runs out of the room for help.

The Nanny (Bette Davis) withholds Penelope’s (Jill Bennett) life-saving medicine.

Later, Joey visits his mother in the hospital and the two are reconciled. The doctor assures Virgie that Nanny will be well cared for at the institution where she has been confined, and that she may one day fully recover.

Bette Davis was wise enough to know, and honest enough to admit, that her glamour days were over when she appeared in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962). “I have always believed in an enormous variety of parts,” Davis said on the BBC, “much more than I’ve been given credit for. The Nanny, for instance, is a complete departure from anything I’ve ever played.” Actually, Bette Davis was not the first actress on Hammer’s list. “My first choice,” Jimmy Sangster told Ted Newsom, “was Greer Garson, believe it or not. I even went down to her ranch in Santa Fe to show her the script. For some reason, she didn’t want to do it.” With “second choice” Bette Davis on board, The Nanny began production at Elstree on April 5, 1965, on a seven week schedule, including ten days in London. Seth Holt, described in Fasten Your Seatbelts as “a kindly, bluff, outwardly charming individual, but actually a churning mass of tensions and neurosis,” had the unenviable task of directing the former Hollywood queen.

Holt said,

Davis got the flu during shooting, and sometimes she’d stay away altogether, holding up shooting while she sent in day-to-day reports on her condition. When she was on the set, still sniffling and coughing, she was drinking out of everyone’s glasses and wheezing in her co-actors’ faces in the best show-must-go-on manner. Oh, it was hell! She was always telling me how to direct. When I did it her way, she was scornful. When I stood up to her, she was hysterical.

Jimmy Sangster, however, saw it differently.

He told the authors (August, 1993), “I thought she was the most professional actress I ever worked with.” Despite the battles between The Nanny and her director, the production ended on schedule, was trade shown on October 1, and premiered at the Carlton on October 7. Unfortunately, young William Dix, who stole every scene he was in, could not attend due to the film’s “X” certificate. Dix had to be content with being photographed with James Carreras in the lobby and with a private screening a month later. The Nanny was released in America on October 27, and took over $260,000 in one week in New York City alone. It went out on the ABC circuit on November 7 and earned £3,600 at one theatre in five days. At the year’s end, The Nanny was named to The Kinematograph Weekly’s top moneymaker list after being in release for only two months. Reviewers were as pleased as the patrons. The Daily Express (October 8, 1965): “Adult horror, taut and tense”; The Evening Standard (October 8): “Nicely chilled suspense”; The Evening News (October 8): “Miss Davis is likely to change the universal concept of Nannydom.”

Bette Davis was “the most professional actress I ever worked with,” said Jimmy Sangster.

While The Nanny was in pre-production, James Carreras approached the BBC and ITV networks with an offer to sell them a package of thirty-nine Hammer horror and science fiction movies. Both turned him down, but later purchased all of the offered pictures individually. Carreras also wanted to break into TV production and planned to film three pilots, including a Quatermass adventure. Nothing came of the idea, which seems to be a better concept than the eventually produced Journey to the Unknown.

Although The Nanny was not strictly a horror movie, it delivered as many chills as anything Hammer produced in the sixties. Bette Davis gave what is probably the best performance by an actress in a Hammer film, but at a cost—both financial and emotional. The supporting cast was excellent. William Dix was more frightening than Dracula, and Jill Bennett’s heart attack, one of the film’s “highlights,” was almost too real to watch. The Nanny was sold to American television in September, 1966, for $400,000, which nearly paid for its production.

Released January 9, 1966 (U.K.), January 12, 1966 (U.S.); 90 minutes; Technicolor (U.K.), Deluxe Color (U.S.); Techniscope; 8100 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios, England; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Executive Producer: Anthony Hinds; Screenplay: John Sansom, based on an idea by John Elder, based on the character created by Bram Stoker; Director of Photography: Michael Reed; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Music: James Bernard; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Production Manager: Ross MacKenzie; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Special Effects: Les Bowie; Camera: Cece Cooney; Assistant Director: Bert Batt; Sound Recordist: Ken Rawkins; Editor: Chris Barnes; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Continuity: Lorna Selwyn; Wardrobe: Rosemary Burrows; Hairstyles: Frieda Steiger; Sound Editor: Roy Baker; U.K. Certificate: X.

Dracula (Christopher Lee) tries to save himself from a watery death in Dracula—Prince of Darkness. (Note anachronistic truck in upper left corner.)

Christopher Lee (Dracula), Barbara Shelley (Helen Kent), Andrew Keir (Father Shandor), Francis Matthews (Charles Kent), Suzan Farmer (Diana Kent), Charles Tingwell (Alan Kent), Thorley Walters (Ludwig), Philip Latham (Klove), Walter Brown (Brother Mark), George Woodbridge (Landlord), Jack Lambert (Brother Peter), Philip Ray (Priest), Joyce Hemson (Mother), John Maxim (Coach Driver).

At a small village in the Carpathian Mountains, English tourists Charles Kent (Francis Matthews), his wife Diana (Suzan Farmer), Charles’ brother Alan (Charles Tingwell) and Alan’s wife Helen (Barbara Shelley) meet Father Shandor (Andrew Keir), who warns them to avoid the castle that lies near the village of Carlsbad. The next day, the Kents’ hired coach driver (John Maxim) brings the carriage to a halt at the outskirts of Carlsbad, telling the travelers that he will not enter the village after dark. When Charles and Alan protest, the frightened driver orders them off at knife-point.

A driverless coach soon appears and, after the vacationers have climbed aboard, heads directly for the forbidden castle. There Klove (Philip Latham), an eerie-looking servant, explains that his late master Count Dracula left him instructions to see to the needs of travelers stranded in the area. When Alan explores the castle late that night, Klove knifes him and, suspending his corpse with a rope above a coffin filled with human ashes, cuts his throat. Alan’s blood pours into the coffin and the ashes take on the form of Count Dracula (Christopher Lee). Klove next lures Helen to the scene and she becomes Dracula’s first new victim. Stalked the next night by Dracula and the now-undead Helen, Charles and Diana ward off the vampires with crosses and escape in Klove’s carriage.

Christopher Lee in Dracula—Prince of Darkness.

Shandor finds the terrorized tourists and takes them to his Kleinberg monastery. But Dracula has traced them to the holy retreat and gains admittance by taking telepathic control of the weak-minded bookbinder Ludwig (Thorley Walters). Dracula and Helen gain access to Diana’s room, but she is saved by the timely arrival of Charles and Shandor. Helen is later captured by other monks, and as Charles looks on in horror, she is staked through the heart by Shandor.

Meanwhile, Dracula abducts Diana and places her body in a coffin in a wagon which is driven back to the vampire’s castle by Klove. Charles and Shandor pursue them on horseback, shooting Klove. Dracula’s coffin (with the Count inside) falls from the wagon, down an embankment and across the frozen surface of the castle moat. Bursting out, the vampire fights with Charles on the ice as Shandor—remembering that running water is fatal to the undead—directs his riflefire at the ice. Dracula drops through a hole in the ice and descends to his doom in the icy water.

After an eight year wait, Hammer finally filmed its second Dracula picture. Christopher Lee (either fearing typecasting or asking for too much money) was not included in the misleadingly titled semi-sequel, The Brides of Dracula. Since his first appearance as Dracula, Lee had become Hammer’s resident character star, playing a mummy, pirates, a drunken cad, an oriental, and even a romantic hero. He had also developed a career on the Continent due to his fluency in several languages and, no doubt, felt it safe to play Dracula again.

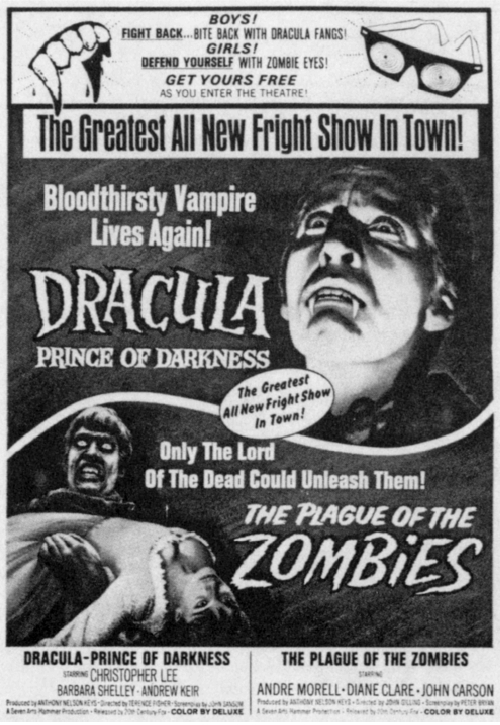

Despite the juvenile advertising gimmicks, an excellent double feature.

Terence Fisher and Jimmy Sangster are rightfully given credit for creating the style of the Hammer Dracula series, yet this was only their second—and last—association with the character. After Dracula—Prince of Darkness, the series would become less interesting productions guided by lesser hands. Sangster was, apparently, not satisfied with the finished picture and appears in the credits as “John Sansom.” Despite having almost a decade to plan the Count’s return, the results are disappointing. Setting the tone for the rest of the series, Dracula seems to be an afterthought and not the film’s central character. Still, no Hammer Dracula that followed would be an improvement, given Terence Fisher’s understanding of vampire lore and of the sexual nature of the monster. Fisher told interviewers Sue and Colin Cowie:

He’s basically sexual. He has the powers of evil to prey on the victims’ sexual feelings so that they believe at the moment he bites it is the culmination of a sexual experience. This is because he is the personification of evil and will always prey on the weakness of every victim, no matter whether its greed or sexuality. His is the personification of temptation.

Dracula appears on screen for the first time without dialogue. Hammer stated that the character was an “embodiment of evil,” and Lee claimed that he refused to speak the lines given him, so use your own judgment. Actually, he had little to say in the first film, and not much worth hearing in later pictures. Also gone from the mix was Peter Cushing’s Van Helsing, replaced by a new—and very different—character, Father Shandor.

After the completion of The Gorgon, Bray Studios was shut down for almost a year for repairs. James Carreras had a novel plan for the reopened studio. “We shall make four horror pictures,” he said (The Daily Cinema, January, 1965). “The titles have not yet been decided, but the pictures will be made back-to-back, in pairs, and released as two of the greatest all-horror programs seen in years!” Filming began on Dracula—Prince of Darkness on May 31, 1965, and concluded on July 4. Almost immediately, Rasputin—The Mad Monk was begun, using much of the same cast, crew, and sets. The third film in the package, The Plague of the Zombies, began on July 28, 1965, followed by The Reptile (September 13). Dracula was paired with Zombie, and the duo was released on January 9, 1966, on the ABC circuit following a December 17 trade show. They took £10,190 on opening day, double the normal amount, and even most reviews were positive. The London Times (January 9, 1966): “The latest Dracula is the best of those they have made up to now”; The Kinematograph Weekly (December 30, 1965): “This is an extremely well-made example of its classic ghoulish horror”; Films and Filming (March, 1966): “Christopher Lee, bloodshot and speechless, makes a powerful figure out of Dracula”; and Variety (January 9, 1966): “Terence Fisher has directed it with his usual know-how.”

The cast was one of Hammer’s strongest for a Dracula film, with Barbara Shelley a standout. “Terry pointed out that when one becomes a vampire,” she told Al Taylor (Little Shoppe of Horrors 7), “one’s sexual proclivities are no longer heterosexual. I did, in fact, do a lot of preparation for this particular role because I wondered how one could play a vampire as the epitome of evil and decadence. So, I went back to my old days when I used to study the old Greek dramas and studied the use of that sort of feeling the Furies.” Christopher Lee saw his character (Films and Filming) as, “A man of great power, presence, physical impact. I see him as an abhuman who is controlled by a force that is beyond his own powers of control.” Andrew Keir’s priest was one of the screen’s few lusty holy men, warming his bottom in front of an entire tavern-full of people, guzzling wine, and carrying a rifle slung across his shoulder. Francis Matthews, Suzan Farmer, and Charles Tingwell managed to give their stock characters more realism than similar roles would receive in future Hammer Draculas.

The script created more than the usual problems with the censor, who rejected it three times because of its “violent content.” Considering the graphic throat-slitting given to Charles Tingwell that appears in the film, one shudders at what must have been excised. Another problem was caused by Suzan Farmer’s forced drinking of Dracula’s blood in one of the few scenes in the film actually taken from Bram Stoker. As usual, James Bernard contributed an excellent score, and Bernard Robinson’s sets were up to his high standard. “I’ve tried to give the decor and the rooms a feeling of uncertainty,” he said, “everything a little off-center, just enough to disturb the eye but looking ostensibly normal.” It all added up to a superior horror package that was one of Britain’s top ten money winners that year.

Released March 6, 1966 (U.K.), April 6, 1966 (U.S.); 92 minutes; Technicolor (U.K.), DeLuxe Color (U.S.); Cinemascope; 8196 feet; a Hammer–7 Arts Production; Released by Warner-Pathe (U.K.), 20th Century–Fox (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios; Director: Don Sharp; Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay: John Elder; Director of Photography: Michael Reed; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Roy Hyde; Production Manager: Ross Mackenzie; Camera: Cece Cooney; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Sound Recordist: Ken Rawkins; Sound Editor: Roy Baker; Continuity: Lorna Selwyn; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Hair Styles: Frieda Steiger; Wardrobe: Rosemary Burrows; Music: Don Banks; Music Supervisor: Philip Martell; Assistant Director: Bert Batt; Dance Director: Alan Beall; U.K. Certificate: X.

Christopher Lee (Rasputin), Barbara Shelley (Sonia), Richard Pasco (Dr. Zargo), Francis Matthews (Ivan), Suzan Farmer (Vanessa), Dinsdale Landen (Peter), Renee Asherton (Tsarina), Derek Francis (Innkeeper), Alan Tilvern (Patron), Joss Ackland (Bishop), John Welsh (Abbott), Robert Duncan (Tsarvitch), John Bailey (Court Physician).

Czarist Russia. Rasputin (Christopher Lee), a debauched peasant monk, has mysterious healing powers which he demonstrates by saving a woman’s life. Forced to flee due to his violent behavior, he sets off for the capital in St. Petersburg. After winning a drinking contest against the alcoholic Dr. Zargo (Richard Pasco), he offends the Czarina’s Lady in Waiting, Sonia (Barbara Shelley). She is “slumming” with Vanessa (Suzan Farmer), her brother Ivan (Francis Matthews), and her own brother Peter (Dinsdale Landen). Sonia inexplicably falls under Rasputin’s power and, at Dr. Zargo’s apartment where he has taken up residence, becomes the monk’s “lover.”

Christopher Lee in one of his favorite roles as Rasputin—The Mad Monk.

Sonia and Vanessa are responsible for the Royal Child (Robert Duncan), and Rasputin orders Sonia to injure the boy so that he can heal him and gain the Czarina’s favor. After healing the child, Rasputin is accepted at Court, and installs Dr. Zargo as Court Physician. Tired of his “relationship” with Sonia, he causes her to commit suicide. Dr. Zargo, fearing Rasputin’s power, enlists Ivan and Peter as allies. After mutilating Peter, Rasputin is lured to Ivan’s home with the promise of “meeting” Vanessa. There, after being poisoned and stabbed, he is thrown out a window to his death by Ivan, but Dr. Zargo has died in the struggle.

Rasputin was one of Christopher Lee’s favorite roles—“Certainly one of the best parts I ever had,” he said (The Films of Christopher Lee). “One of the best performances I’ve given.” Lee is quite good and is the main reason to watch the film, which looks uncharacteristically cheap despite B.R. sets. One never gets the feeling of being anywhere but on the film set, and certainly not in Czarist Russia. Although Rasputin was a real historical character, the film has little to do with history, since director Don Sharp was aware of possible legal difficulties. “It was more historically accurate in the first draft,” he said (Fangoria, No. 31). “But Count Youssaupoff was still alive; there was the threat of a lawsuit, so we had to change everything.” He candidly told The Kinematograph Weekly (July 15, 1965), “Let’s be quite honest that this is a Hammer film, and is not by any means a historical biography.” Rasputin is a fascinating character, and Hammer was not the first or last to film his story. Others to play the role include Lionel Barrymore (Rasputin and the Empress, 1932), Edmund Purdom (The Night They Killed Rasputin, 1962), Gert Frobe (Rasputin, 1967), and Tom Baker Nicholas and Alexandra, 1971). Boris Karloff even had a go on television in Suspense (1953).

Rasputin—The Mad Monk was, like She, a subject too big for Hammer to realistically take on. A film like this needs a much larger budget and location shooting to be believable. Viewers could easily be tricked into accepting Bray as a fantasy Transylvania, but not a realistic Russia. Filming was done under hurried conditions, and it shows. Francis Matthews explained when interviewed by Sue and Colin Cowie, “On the day we finished Dracula—Prince of Darkness, we started on Rasputin. We used the same sets revamped. We did the exteriors on the ice, while the palace set was redressed. I had a marvelous fight with Christopher Lee that wasn’t seen in the finished film. I don’t know why they cut it—usually they keep all the action and cut the dialogue scenes!” Also returning from the Dracula picture were the female leads. Barbara Shelley was outstanding in both, creating two memorable characters for a company that generally played down female roles.

Christopher Lee is the life of the party in Rasputin—The Mad Monk.

The film began production on June 8, 1965, and was completed on July 20. Paired with The Reptile, it was trade shown at Studio One on February 14, 1966, and the pair was released on the ABC circuit on March 7. Reviewers were unimpressed. The Kinematograph Weekly (February 24, 1966): “A curiously unconvincing atmosphere”; The Daily Cinema (February 16): “Garbled version with conventional Hammer shocks and historical inaccuracies.” Despite Christopher Lee’s attempts to elevate the film above his other work for Hammer, this is “just” a horror movie—and a fairly entertaining one—but no more. It is similar to Universal’s 1939 Tower of London with Basil Rathbone, Boris Karloff, and Vincent Price: Despite the historical trappings, it is a horror movie at heart.

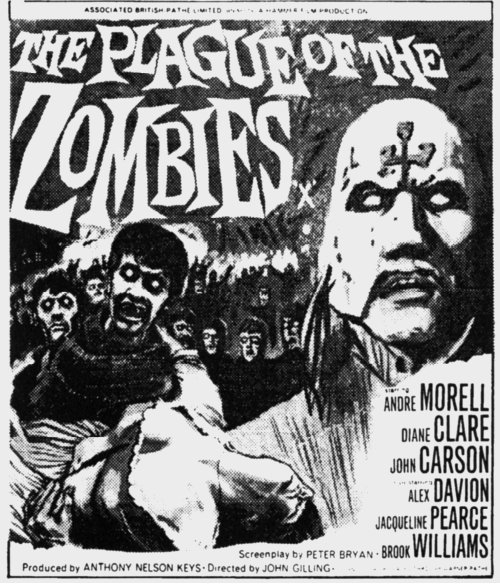

Released January 9, 1966 (U.K.), January 12, 1966 (U.S.); 90 minutes; Technicolor (U.K.), DeLuxe Color (U.S.); a Hammer–7 Arts Film Production; an Associated British–Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios, England; Director: John Gilling; Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Executive Producer: Anthony Hinds; Screenplay: John Elder, Peter Bryan, based on an original story by Peter Bryan; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Production Designer: Bernard Robinson; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Production Manager: George Fowler; Editor: Chris Barnes; Assistant Directors: Bert Batt, Martyn Green; Camera: Moray Grant; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Sound Recordist: Ken Rawkins; Sound Editor: Roy Baker; Continuity: Lorna Selwyn; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Hairstylist: Frieda Steiger; Wardrobe: Rosemary Burrows; Special Effects: Bowie Films Ltd.; Music: James Bernard; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; U.K. Certificate: X.

Andre Morell (Sir James Forbes), Diane Clare (Sylvia Forbes), Brook Williams (Dr. Peter Thompson), Jacqueline Pearce (Alice Thompson), John Carson (Squire Clive Hamilton), Alex Davion (Harry Denver), Michael Ripper (Sergeant Swift), Marcus Hammond (Martinus), Dennis Chinnery (Constable Christian), Louis Mahoney (Coloured Servant), Roy Royston (Vicar), Ben Aris, Tim Condron (John Martinus/Zombie), Bernard Egan, Norman Mann, Francis Willey (The Young Bloods), Jerry Verno (Landlord), Jolyan Booth (Coachman), Del Watson, Peter Diamond (Zombies).

Sir James Forbes (Andre Morell) receives a letter from former student Peter Thompson (Brook Williams) asking for his mentor’s advice concerning a strange disease reaching epidemic proportions in the Cornish village where Thompson practices. Forbes’ daughter Sylvia (Diane Clare) suggests they pay the Thompsons a visit since Thompson’s wife Alice (Jacqueline Pearce) was her best friend at school.

Sir James and Thompson open the grave of one of the plague victims to perform a post mortem, but they find the coffin empty. Police Sgt. Swift (Michael Ripper) catches them in the act but Sir James convinces the police officer to work with them to find the answers to all the mysterious events taking place in the town.

Walking corpses are seen near an abandoned mine on the estate of Hamilton (John Carson), the local squire. After Alice is killed, Sir James determines that someone in the village has been practicing voodoo. He believes that Alice has been victimized and states that he intends to watch over her grave. Against Sir James’ wishes, Peter goes with him. That night, they witness the rebirth of Alice as a zombie. Thompson, frozen with fear, watches as Alice moves toward him threateningly. Sir James grabs a sexton’s shovel and decapitates the corpse.

Sir James confronts Squire Hamilton and accuses him of practicing voodoo rites (Hamilton learned voodoo in Haiti and created the zombies to work the still-profitable mine). When Hamilton denies the charges, Sir James leaves, but then sneaks back in and watches while hiding as Hamilton recites the voodoo rites that will mentally link him with Sylvia. Sylvia “hears” the summons and, in a hypnotic trance, makes her way to the mines. Thompson follows her out into the night.

In a battle with a masked man in ceremonial robes in Hamilton’s study, a lamp is overturned and the room is set ablaze. Sir James escapes and makes his way to the mines, where Alice is about to be sacrificed. But the fire in Hamilton’s home ignites a number of clay figures representing Hamilton’s victims. The zombies, magically linked to these figures, begin to smolder and then turn on their master. Thompson and Sylvia take advantage of the diversion to get away, making it out of the mine before it is enveloped in flames.

Hammer’s third film in their twin double feature package started production on July 28, 1965—just over a week after the completion of Rasputin—The Mad Monk. Two days earlier, Anthony Hinds left for New York to join James Carreras and meet with 7 Arts to discuss the upcoming One Million Years B.C. The Plague of the Zombies combined shooting at Bray with location work at Black Park, Oakley Court, and Cobham under John Gilling’s direction. He had previously directed three costume adventures for Hammer, and this was his first horror movie for the company. “The Plague of the Zombies and The Reptile,” he said (Little Shoppe of Horrors 7), “were offered to me on a back-to-back basis. They each contained a good idea which attracted me. I agreed to undertake the job on the condition that I had full control of the scripts, which I re-wrote more or less as I went along.” Chief villain John Carson recalled that Gilling“had a reputation of being a bit of an SOB. I found John to be a man of humor, discipline, energy, kindness with schmaltz, imagination, and passion. He loved the business, but it wasn’t the be all and end all. John had just the right mixture of knowing when to cool you down and when to kick your backside.”

Andre Morell, in his seventh Hammer film, delivered his typically excellent performance. Morell had the ability to get roles in both big (Ben Hur, 1959) and small pictures, and Hammer was fortunate to get his services as often as they did. He was on vacation when his agent contacted him. “My agent rang me,” he told David Soren, “and said, ‘Come back and do this Hammer film for good money.’ ‘What is it?’ I asked. He stammered out that this was … a-uh-costume drama. I asked him what it was called, and he said The Plague of the Zombies. I said I didn’t believe it and had to ask him what it was about. I absolutely loved it. We had great fun. To make a film like this, of course, one doesn’t believe in zombies, but one says this is it and does it seriously.” Morell added a touch of sly humor to his authoritarian role, resulting in one of Hammer’s best heroes.

Top: Brook Williams and Tim Condron rehearse on the set of The Plague of the Zombies. Bottom: Brook Williams, Diane Clare and Andre Morell find Jacqueline Pearce’s body in The Plague of the Zombies.

“Cornwall” via Bray Studios. Sound stages peek out from behind the tin mine set in this scene from The Plague of the Zombies.

The fifteen “zombies” made their first appearance on the set on August 20. No one zombie had any real impact, and all took a back seat to John Carson, similar to the situation in White Zombie (1932) with zombie master Bela Lugosi. Filming ended on September 6, and by mid–October, Hammer had decided to pair The Plague of the Zombies and Dracula—Prince of Darkness, forming the decade’s best horror package. “People have to remember,” enthused Anthony Nelson-Keys (The Daily Cinema, August 10, 1965), “that these are morality tales, not unlike Greek heroes crusading against evil. Surely it’s far better to make costumed horror films, rather than those modern sadistic and neurotic films where there are definite everyday associations and messages.” Unfortunately, this is the type of picture Hammer would soon be making. A trade show was held at Studio One on December 20, 1965, and the double feature went into general release on January 9, 1966, to mostly good reviews. The Daily Cinema (December 29, 1965): “John Gilling has contrived some truly terrifying effects.” The Kinematograph Weekly (December 30): “Like nearly all Hammer films, this is very well staged, and one or two of the action scenes are as good as anything in the way of cinematic excitement”; and The New York Post (May 5, 1966): “So predictable that its standard scare tactics are merely tedious.” The Plague of the Zombies has, over the years, attracted more than one pretentious critique. When the British Film Institute ran a Hammer tribute in the fall of 1971, the program guide pointed out, “The conflagration at the end of the film is an apt metaphor for suggesting the burning anger and fiery rebellion of the exploited who turn on their oppressors.”

The first of John Gilling’s Cornwall classics was unappreciated in its day, but time has since proved otherwise.

This aside, The Plague of the Zombies did deliver more than simply routine shocks. Andre Morell and Diane Clare were a charming father-daughter team, balanced by John Carson and Alex Davion as the arrogant villains. The “Young Bloods” are reminiscent of Sir Hugo’s pack of degenerates in The Hound of the Baskervilles, which is not surprising, since Peter Bryan wrote both scripts. Bernard Robinson’s sets convincingly set a place and time despite the more rushed than usual conditions, and James Bernard’s outstanding score added the right touch to one of Hammer’s best sixties horrors.

Released March 6, 1966 (U.K.), April 6, 1966 (U.S.); 91 minutes; 8140 feet; Technicolor (U.K.), DeLuxe Color (U.S.); a Hammer-7 Arts Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at Bray Studios, England; Director: John Gilling; Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay: John Elder; Music: Don Banks; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Executive Producer: Anthony Hinds; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Production Manager: George Fowler; Editor: Roy Hyde; Assistant Director: Bill Cartlidge; Camera: Moray Grant; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Sound Recordist: Bill Buckley; Sound Editor: Roy Baker; Makeup: Roy Ashton; Hairstylist: Frieda Steiger; Wardrobe: Rosemary Burrows; Special Effects; Les Bowie; Continuity: Lorna Selwyn; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; U.K. Certificate: X.

Noel Willman (Dr. Franklyn), Jennifer Daniel (Valerie Spalding), Ray Barrett (Harry Spalding), Jacqueline Pearce (Anna), Michael Ripper (Tom Bailey), John Laurie (Mad Peter), Marne Maitland (Malay), David Baron (Charles Spalding), Charles Lloyd Pack (Vicar), Harold Goldblatt (Solicitor), George Woodbridge (Old Garnsey).

Returning home late one evening to his cottage on the Cornwall heath, Charles Spalding (David Baron) finds a note asking him to come to Dr. Franklyn’s manor. When his knock goes unanswered, Charles enters the house and is attacked by a shadowy figure that bites his throat. Charles topples down a flight of stairs to his death. Franklyn (Noel Willman) and his servant Malay (Marne Maitland) converge on the body, whose face is grotesquely mottled and blackened. Under cover of darkness, Malay dumps the body in the nearby churchyard.

Jacqueline Pearce attacks in The Reptile.

Charles’ brother Harry (Ray Barrett) inherits Charles’ cottage and moves in along with his wife Valerie (Jennifer Daniel). Harry suspects that Charles did not die of heart failure and enlists the aid of Mad Peter (John Laurie), a local eccentric, to help unravel the mystery. But Mad Peter is also killed in the same manner as Charles.

Franklyn’s daughter Anna (Jacqueline Pearce) invites the Spaldings to dinner. In the over-heated house, Anna plays a tune on a sitar which causes her father to react violently and smash the instrument.

Harry and one of the locals, pub proprietor Tom Bailey (Michael Ripper), disinter the bodies of Charles and Mad Peter and find on their throats the bite mark of a king cobra. Later, Harry finds a note from Anna asking for help. He goes to Franklyn’s manor where he, too, is attacked by the nightmare creature—part-woman, part-reptile. Harry makes it back home and Valerie cuts into the wound and draws out the venom.

As Harry rests, Valerie finds the note from Anna and visits the Franklyn home, secretly following Franklyn as he descends into his cellar armed with a sword. In the cellar is a sulfur pit and a female figure covered by a blanket. When Franklyn raises his sword to strike, he is attacked by Malay. Franklyn tosses Malay into the sulfurpit.

Upstairs, Franklyn tells Valerie that he is responsible for Anna’s horrible condition. Years before, he and Anna lived in Borneo where Franklyn antagonized a cult of snake worshippers who subsequently abducted Anna and, through a series of secret rituals, transformed her into the Reptile. The Franklyns managed to escape the country but were found by one of the cult’s members, Malay, who continued to perform the ritual that transforms Anna into the monster.

A fire which started during Franklyn’s fight with Malay spreads through the manor. The Reptile attacks and kills Franklyn and then chases Anna, who is rescued by Harry and Tom. The three escape as the houseand the Reptile are completely engulfed in flames.

Although The Reptile is the least appreciated of Hammer’s twin double features of 1965, it is one of the company’s most underrated fantasies. It was a rare attempt by Hammer to create a “new” monster—and a female one at that—but the creature’s roots could actually be traced to Universal’s Cult of the Cobra (1955). Jacqueline Pearce was the only Hammer actress to play two monsters (a zombie and a snake creature), and she headed a spirited, if “second team,” cast. Noel Willman and Jennifer Daniel returned to Hammer for the first time since The Kiss of the Vampire, but it was Michael Ripper who was finally singled out for some praise. The Daily Cinema (February 18, 1966) felt that, “Ripper’s portrayal of the dullest character in all these horror movies, the helpful friend, is a most sensitive job of acting. It’s time they started giving awards for the most distinguished roles, rather than for the best performances in the best roles: then the artists who are truly the backbone of the industry would get the credit that’s due to them.” Ripper commented (Photon), “I think that you can get away with a lot more when it’s in period, because people will accept a possibility that they just wouldn’t accept in modern life. The more outlandish your story, the more necessary it probably becomes to put it in a remote time.”

The Reptile began filming on September 13, 1965, and concluded on October 22. The Cornish village on the Bray lot was the same as in The Plague of the Zombies, and John Gilling made every effort to disguise that fact by using different camera angles. Nearby Oakley Court stood in for the exterior of the Franklyns’ manor house. A trade show was held at Studio One on February 16, 1966, and The Reptile went into release, with Rasputin—The Mad Monk, on March 6, to positive reviews. The Kinematograph Weekly (February 24): “Directed with intelligence—an excellent shocker”; and The Daily Cinema (February 18): “Gilling and scriptwriter Elder have gone to great pains to promote suspense through characterization and inter-relationship.”

This was the last Hammer film for which Roy Ashton was solely responsible for the makeup, and the result was credible except when in closeup. Fortunately, Gilling confined the creature to shadows for most of the film, “Lewton style,” giving only fleeting glimpses of the monster. The Reptile is about as good as a supporting feature horror movie gets. It may have been a “B” movie, but all concerned deserve an “A” as Hammer, once again, put all of its investment in the picture on the screen.

Hammer’s attempt to create a new monster almost worked.

Released December 30, 1966 (U.K.), February 21, 1967 (U.S.); 100 minutes (U.K.), 91 minutes (U.S.); Technicolor (U.K.), Deluxe Color (U.S.); filmed in Panamation; 9031 feet; a Hammer-7 Arts Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at Associated British/EMI Studios, Elstree, England, and on location in the Canary Islands; Director: Don Chaffey; Producer, Screenplay: Michael Carreras; Associate Producer: Aida Young; Adapted from an original screenplay by Michael Novak, George Baker, Joseph Frickett; Special Animated Effects: Ray Harryhausen; Music and Special Music Effects: Mario Nascimbene; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Art Director: Robert Jones; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Costume Design: Carl Toms; Director of Photography: Wilkie Cooper; Editor: Tom Simpson; Assistant Director: Denis Bertera; Camera: David Harcourt; Continuity: Gladys Goldsmith, Marjorie Lavelly; 2nd Unit Camera: Jack Mills; Assistant Art Director: Kenneth McCallum Tait; Mechanical Special Effects: George Blackwell; Sound Editors: Roy Baker, Alfred Cox; Sound Mixer: Bill Rowe; Sound Dubbing: Len Shilton; Makeup: Wally Schneiderman; Hairdresser: Olga Angelinetta; Wardrobe Mistress: Ivy Baker; Prologue Designed by: Les Bowie; Production Manager: John Wilcox; Publicity Directors: Alan Thompson, Robert Webb; Stills Cameraman: Ronnie Pilgrim; 1st Camera Assistant: Geoffrey Glover; Camera Assistant: E. Deason; 2nd Camera Operator: Kenneth Nicholson; Draughtsman: Colin Monk; Scenic Artist: Bill Beavis; 1st Assistant Editor: Robert Dearberg; Assistant Editors: Antony Sloman, Chris Barnes; 2nd Assistant Director: Colin Lord; 3rd Assistant Director: Ray Atchelor; Production Secretary: Eileen Mathews; Animal Sculptures: Arthur Hayward; Executive Producer: Anthony Hinds; U.K. Certificate: A.

John Richardson and Raquel Welch seek a well-hidden refuge in One Million Years B.C.

Raquel Welch (Loana), John Richardson (Tumak), Percy Herbert (Sakana), Robert Brown (Akhoba), Martine Beswick (Nupondi), Jean Wladon (Ahot), Lisa Thomas (Sura), Malya Nappil (Tohana), Richard James (Young Rock Man), William Lyon Brown (Payto), Frank Hayden (1st Rock Man), Terence Maidment (1st Shell Man), Micky DeRauch (1st Shell Girl), Yvonne Horner (Ullah).

When caveman Tumak (John Richardson) fights with his father, Akhoba (Robert Brown), chief of the Rock Tribe, Tumak is defeated and sent into exile. His mate Nupondi (Martine Beswick) is claimed by Tumak’s brother Sakana (Percy Herbert). Tumak wanders through the rugged terrain for days until he reaches the ocean where he collapses. A group of women appears and one of them, Loana (Raquel Welch), is tending to him when a giant turtle approaches menacingly. Loana blows into a large conch shell, attracting warriors who attack the giant beast with their spears.

While Tumak regains his strength under the care of Loana and other members of her Shell Tribe, his father, Akhoba, is badly wounded when he is pushed off a cliff by Sakana. Sakana proclaims himself chief of the Rock Tribe.

This was the way it wasn’t!

Tumak is adjusting to life among the gentle Shell People, learning how to use a spear from warrior Ahot (Jean Wladon) and how to spear-fish from Loana. When an Allosaurus attacks one of the tribe children, Tumak kills the monster. But he soon clashes with Ahot and is caught stealing. The chief of the Shell People banishes him and Loana follows.

Tumak and Loana return to the Rock Tribe’s territory. On the journey, the couple narrowly escape being captured by ape-like cave dwellers and witness a battle between a Ceratosaurus and a Triceratops. When Loana is captured by Sakana and his warriors, Tumak fights and defeats his brother.

Loana and Tumak return to the Rock Tribe dwelling. Loana is attacked by Nupondi, who wants to reclaim Tumak as her mate, but Loana wins the battle. Tumak becomes leader of the tribe while she teaches them the ways of her people. She is teaching them to swim when she is seized and carried away by a Pterodactyl. Loana gets away when the giant bird battles with another of its species.

The Shell People find her and she convinces Ahot and others to take her back to Tumak, who is overjoyed to find his mate alive. Ahot and his warriors are about to return to the sea when Sakana and his followers attack Tumak. Ahot joins forces with Tumak to fight the dissenters, and during the fight, Tumak kills Sakana.

Peace for the Rock Tribe finally seems at hand when nature intervenes in the form of a violent volcanic eruption. Many of the tribe are killed by falling rocks, others are swallowed up by the heaving earth. Afterwards, only a handful of the two tribes survive the tumult. Tumak and Loana band together with the survivors to find a new home and a bright future together.

One Million Years B.C. was Hammer’s biggest financial gamble, boasting a budget in excess of £2.5 million. James Carreras (The Daily Cinema, January, 1965) called the project “A fantastic, fascinating, and spectacular subject.” It was a remake of Hal Roach’s One Million B.C. (1940), using Ray Harryhausen–animated monsters, rather than magnified iguanas, as the original had done. Lacking dialogue—at least that anyone could understand—the film would depend on its visuals for success. Two of the “visuals,” in addition to Harryhausen’s creatures, were Raquel Welch and John Richardson, reprising the roles played by Carole Landis and Victor Mature. Harryhausen began preliminary work at Elstree on May 27, 1965. He recalled (Little Shoppe of Horrors 6), “Hammer had seen a number of my films, and then they got the rights to One Million B.C. It was on-and-off and on-and-off for quite a while before it actually got started.” He began collecting photographs from the Museum of Natural History in New York and based his model armatures on the skeletons in the British Natural History Museum. Eight models were eventually built. “Accuracy and detail are especially important this time,” Harryhausen said (The Daily Cinema, December 17, 1965), “because we’re dealing with animals that actually once existed.”

Harryhausen worked on his sketches for four months. “I made three or four big drawings,” he told Little Shoppe, “and then I made a lot of storyboard sketches at EMI. I had a year to finish the effects.” After the sketches were approved, he began to construct the models. “Each animal is built with intricate mechanisms inside; some will breathe. The framework is constructed in America, the rest I do myself.” Harryhausen spent six weeks on location, choreographing the actors who would eventually interact with the creatures on film. “I’d have a story conference with Don Chaffey before the scene was done. Naturally, reactions must always be gauged in terms of the limitations of the special effects stage.”

Ray Harryhausen averaged twelve hour workdays at Elstree. “Sometimes,” he said (Daily Cinema, December 17, 1965), “it’s difficult to leave an awkward shot overnight without losing the rhythm of a scene. Also, everything is critical with temperature, which might cause a slight but crucial movement in one of the models. You have to try to finish a shot at a moment when you can cut.” Actress Martine Beswick, interviewed by Steve Swires (Fangoria, 55), recalled Harryhausen as “A lovely man, but sort of a ‘mad scientist’ who was very quiet, and deep and totally committed to what he was doing. For the dinosaur attacks, he rode in the back of a truck mounted with a camera and told us actors where to look and move.” He and director Don Chaffey had worked together previously on Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and had a good relationship. Michael Carreras also admired Chaffey. “Don is an extraordinary man in terms of telling a story with no dialogue.”

Two months before shooting began, Anthony Hinds and James Carreras flew to America to plan publicity strategies with 7 Arts. One used in Britain involved a competition to find a girl to appear in the film. The winner was Yvonne Horner, a secretary from Surrey who appeared as “Ullah.” Principal photography began on October 18, 1965, in the Canary Islands. The picture was launched as Hammer’s 100th, but due to the company’s odd history, it is more likely that One Million Years B.C. was their 116th. By November 20, the unit had returned to film interiors at Elstree, and filming continued until January 7, 1966. Slave Girls would soon begin production on the same sets. Ray Harryhausen completed the special effects by spring; due to his workload, the film’s pre-credit sequence was designed by Les Bowie, who claimed that he created the earth in six days for £1100 and made his “lava flows” with porridge.

One Million Years B.C. was trade shown on October 25, 1966, at the Warner, and the film went into general release on the ABC circuit on December 30. Although many critics dismissed the movie as juvenile, audiences knew entertainment when they saw it. The New York World Journal Tribune (February 22, 1967): “This idiot tale won’t even amuse the kiddies”; The New York Morning Telegraph (February 22): “The film might be best described as Bikini Beach with dinosaurs”; Films in Review (March): “The monsters are realistically constructed and manipulated and, technically, their involvement with humans in the same scenes is beyond reproach”; Variety (December 28, 1966): “It is the trick photography that does the trick”; and Sight and Sound (Winter 1966): “The film is a huge success.” It certainly was, and by the end of January, 1967, the trades were reporting “mammoth business.” The Daily Cinema (January 6) felt that “The spectacular picture looks set to become one of the biggest grossing productions of the year.” In fact, D.J. Goodlatte, president of ABC Theatres, reported that One Million Years B.C. had broken the circuit’s all-time record. All told, the film made the Top Ten Box Office Winners for 1967, earned $9 million, and launched Raquel Welch on a long and successful career.