Released November 19, 1967 (U.K.), March, 1968 (U.S.); 100 minutes (U.K.), 98 minutes (U.S.); Technicolor (U.K.), DeLuxe Color (U.S.); a Hammer–7 Arts Film Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/ EMI Studios, Elstree, England; Director: Roy Ward Baker; Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay & Story by: Nigel Kneale; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Music: Tristram Cary; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Art Director: Ken Ryan; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Spencer Reeve; Special Effects: Bowie Films Ltd.; Sound Recordist: Sash Fisher; Sound Editor: Roy Hyde; Makeup: Michael Morris; Wardrobe: Rosemary Burrows; Hairstyles: Pearl Tipaldi; Production Manager: Ian Lewis; Assistant Director: Bert Batt; Casting: Irene Lamb; Camera: Moray Grant; Continuity: Doreen Dearnaley; U.S. Title: Five Million Years to Earth; U.K. Certificate: X.

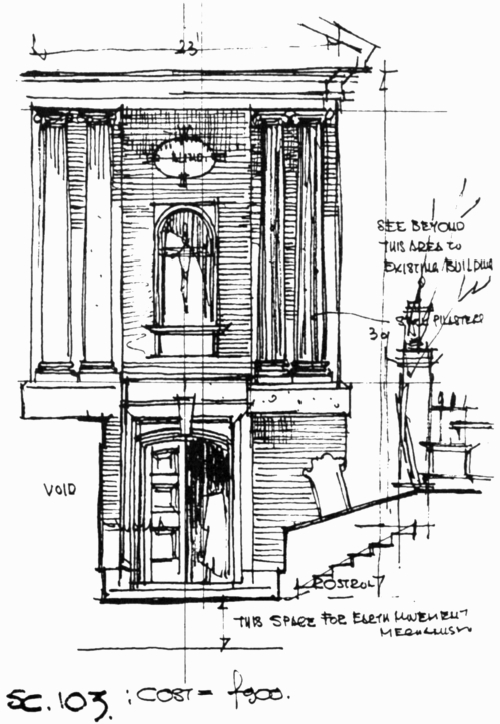

A Bernard Robinson design for Quatermass and the Pit (courtesy of Margaret and Peter Robinson).

Barbara Shelley, James Donald and Andrew Keir stumble upon the missing link in Quatermass and the Pit (photo courtesy of Ted Okuda).

James Donald (Doctor Roney), Andrew Keir (Professor Quatermass), Barbara Shelley (Barbara Judd), Julian Glover (Colonel Breen), Duncan Lamont (Sladden), Bryan Marshall (Captain Potter), Peter Copley (Howell), Edwin Richfield (Minister of Defense), Grant Taylor (Police Sergeant Ellis), Maurice Good (Sergeant Cleghorn), Robert Morris (Jerry Watson), Sheila Steafel (Journalist), Hugh Futcher (Sapper West), Hugh Morton (Elderly Journalist), Thomas Heathcote (Vicar), Noel Howlett (Abbey Librarian), Hugh Manning (Pub Customer), June Ellis (Blonde), Keith Marsh (Johnson), James Culliford (Corporal Gibson), Bee Duffell (Miss Dobson), Roger Avon (Electrician), Brian Peck (Technical Officer), John Graham (Inspector), Charles Lamb (News Vendor).

While building an extension to the London subway system, workmen at the Hobbs End station discover skulls and skeletons of what appear to be subhuman creatures. Further investigation by Dr. Roney (James Donald) and his assistant Barbara Judd (Barbara Shelley) of the National Historical Research Institute reveals a strange missile, thought at first to be an unknown Nazi V-weapon of World War II.

As work continues on the missile, rocket research expert Professor Quatermass (Andrew Keir) studies the history of the area and learns that it has always been associated with demons, dating as far back as the Roman occupation of England. When the door to the missile is finally opened, the scientists are horrified to discover the bodies of locust-like creatures, which Quatermass maintains are dead Martians. Quatermass believed that these beings have influenced the evolution of man and that their power survives.

Quatermass’ theory becomes manifest when a monstrous insect-like horned creature hundreds of feet high materializes above the excavation pit, causing panic in the streets of London. Quatermass learns that whenever a human comes near the creature, which contains all the concentrated forces of evil, that person’s mind is controlled and redirected by the Devil. Quatermass is also reminded of one of the ancient remedies used to battle the devil and the one thing it was purported to fear—iron. With the future of mankind threatened, Dr. Roney drives a large overhead crane into the center of the creature, causing it to dissolve. In so doing, however, he sacrifices his own life.

Professor Quatermass and Dr. Roney meet one of their ancestors in Quatermass and the Pit.

Hammer bought the rights to the BBC serial Quatermass and the Pit shortly after its initial episode was telecast on December 22, 1958. The six-part program starred Andre Morell and, like the first two serials, was a hit. The film version was to start in November, 1961, but was moved back to 1963. Explaining the delay, James Carreras said (New York World Telegraph, October 19, 1963), “Hammer Films steers clear of science fiction. Science fiction films are not easy to make. They call for lots of trick photography which sends the budget soaring and the faking has got to be good. Teenagers are quick to spot the inaccuracies.” The company was finally ready in 1967, and production began on February 27. Filming was moved from Elstree, due to overcrowding, to MGM Borehamwood. The planned director (Val Guest) and star (Peter Cushing) both had to be replaced due to schedule conflicts.

Producer Anthony Nelson-Keys (Little Shoppe of Horrors 7) recalled, “I wanted a director who had a great deal of technical know-how.” He turned to Roy Ward Baker, who sank the Titanic in A Night to Remember (1958). “I was looking for a film after five years in television,” said Baker. “Once I read the script, I thought, ‘This is it!’ It was the most wonderful, bogus, believable clap-trap I’d read in my life!” Andrew Keir stepped in for Cushing and was the best Professor Quatermass in the Hammer series. James Donald traded in his usual military attire for a tweed jacket for his edgy performance as the odd Dr. Roney, but Barbara Shelley stole the film with her intense performance.

Author Nigel Kneale had become well aware of the importance of visuals over words in movies. “More and more scripts,” he said (Daily Cinema), “are going back to the silent era, letting the pictures tell the story and putting the dialogue in a subordinate position.” Roy Ward Baker added (Starlog 180), “We went through the script together and discussed it. Kneale visited the set and saw a bit of the shooting. He was very happy with the picture when it was done.” This was praise indeed, considering Kneale’s dissatisfaction with aspects of the first two pictures. Baker’s reading of James Carreras and Anthony Nelson-Keys was, “They weren’t interested in art. In fact, I was quite anxious not to discuss the underlying overtones with them.” These overtones were quite disturbing, raising many unsavory questions about the origin of man, making Quatermass and the Pit the most intellectually challenging of the series. Like its predecessors, the movie fails only in its special effects.

Hammer’s thought provoking finale to the series, Quatermass and the Pit, was retitled for the American audience.

Filming ended at the end of April, and Quatermass and the Pit was trade shown at the Leicester Square Warner on September 27, 1967. The premiere was held on November 7, and the picture went into general release on November 19. As with the previous films, the Quatermass name was dropped in America, and the title changed to Five Million Years to Earth. Unfortunately, its release coincided with that of Stanley Kubrick’s spectacular 2001. Reviews, on both sides of the Atlantic, were mostly positive. The Sunday Telegraph (November 5, 1967): “The third of an honorable trilogy”; The Morning Star (November 4): “Kneale’s creepy legend was given a new lease on life on the big screen”; The Monthly Film Bulletin (November): “A pity that the most interesting of Kneale’s Quatermass parables proves the least satisfactory as a film”; The Kinematograph Weekly (September 30): “An ingenious and inventive plot”; and The New York Free Press (June 13): “Makes 2001 look like a nursery story.” To really see the story, one should watch the BBC serial with Andre Morell’s excellent acting, and the benefit of a longer running time. However, Hammer’s version is a fine one; an example of thought provoking science fiction at its best.

Released December 24, 1967 (U.K.), June, 1968 (U.S.); 96 minutes (U.K.), 85 minutes (U.S.); Technicolor (U.K.), DeLuxe Color (U.S.); a Hammer–7 Arts Film Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at Pinewood Studios, England; Director: C.M. Pennington-Richards; Producer: Clifford Parkes; Executive Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Peter Bryan; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Chris Barnes; Art Director: Maurice Carter; Music: Gary Hughes; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Sound Editors: George Stephenson, Laurie Barnett, Jack T. Knight; Special Effects: Bowie Films; Fights Arranged by: Peter Diamond; Makeup: Michael Morris; Hairstyles: Bill Griffiths; Production Manager: Bryan Coates; Assistant Director: Ray Corbett; Camera: Moray Grant; Continuity: Elizabeth Wilcox; Wardrobe: Dulcie Midwinter; Casting Director: Irene Lamb; U.K. Certificate: U; MPAA Rating: G.

Barrie Ingham (Robin Hood), James Hayter (Friar Tuck), Leon Greene (Little John), Gay Hamilton (Maid Marian Fitzwarren/Mary), Peter Blythe (Roger de Courtenay), Jenny Till (“Lady Marian”), John Arnatt (Sheriff of Nottingham), Eric Flynn (Alan-a-Dale), Alfie Bass (Pie Merchant), John Gugolka (Stephen Fitzwarren), Reg Lye (Much), William Squire (Sir John de Courtenay), Donald Pickering (Sir Jamyl de Penitone), Eric Woofe (Henry de Courtenay), John Harvey (Wallace), Douglas Mitchell (Will Scarlet), John Graham (Justin), Arthur Hewlett (Edwin), Norman Mitchell (Dray Driver).

In 12th century England, Robin de Courtenay (Barrie Ingham) vows revenge when young Stephen Fitzwarren’s (John Gugolka) father is murdered by Norman overlords led by Robin’s evil cousin Roger (Peter Blythe). When Roger’s father, Sir John (William Squire), learns that King Richard has been captured while returning from the Crusades, he suffers a heart attack and, before dying, includes Robin in his will. Roger tries to enlist his brother Henry (Eric Woofe) to kill Robin, and when he refuses, Roger kills him. Roger orders Robin’s arrest for the murder, but Friar Tuck (James Hayter) knows the truth and helps Robin escape into Sherwood Forest. They are attacked by the Sheriff of Nottingham’s (John Arnatt) men, but the poor forest dwellers rescue them. After Robin shows his prowess with bow and quarterstaff, he becomes their leader. The Sheriff and Roger plan to lure Robin from the forest by executing his friend Will Scarlet (Douglas Mitchell). Robin and his band infiltrate the castle, but he is captured and ordered to hang with Will. With the help of Little John (Leon Greene) and a pie fight orchestrated by Tuck, he escapes.

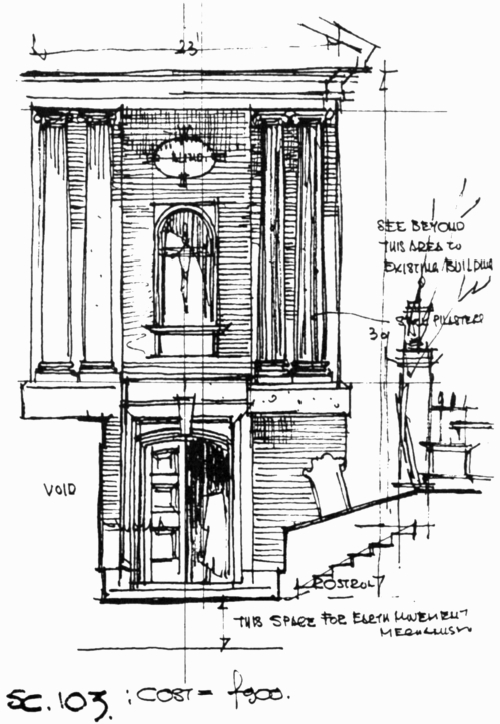

Robin Hood (Barrie Ingham, right) falls into the clutches of his evil cousin Roger de Courtenay, in A Challenge for Robin Hood.

Robin learns that a woman he met at Sir John’s castle disguised as a handmaiden is actually “Lady Marian” Fitzwarren (Gay Hamilton), daughter of the murdered man. She thanks him for helping Stephen, with whom she has been reunited. When the sister and brother are taken prisoner by Roger, he offers himself in exchange. Led by Little John, the men of Sherwood storm Roger’s castle and free their leader. Roger is killed in the battle, and Robin and Marian plan to marry.

Hammer returned to the Robin Hood legend for the third time to fulfill its commitment to produce at least one picture a year for general audiences. Despite a meager budget, an unknown star, and a fledgling director, A Challenge for Robin Hood was an impressive effort. Barrie Ingham, a former member of the Old Vic, had only four films to his credit and, while a far cry from the typical Hollywood leading man, was a worthy successor to the role. Peter Bryan, who scripted some of Hammer’s best movies, contributed his last for the company. His version is more violent than one would expect for a children’s film but, then, this was a Hammer production. Former cameraman C. Pennington-Richard’s directorial debut began on May 1, 1967, at Pinewood, with location shooting done at Bodiam Castle in East Sussex. First time producer Clifford Parkes insisted that his actors play their roles straight. Two members of his supporting cast were reprising their roles from previous productions—James Hayter (Friar Tuck in The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men, 1952) and John Arnatt (the Sheriff in Richard Greene’s television series). Chief villain Peter Blythe recalled for the authors (February, 1992):

Not all of the actors were veterans. The first day of shooting included a young New Zealand actor that was new to the business. The first day went smoothly enough. We were about halfway into the first scene the next morning when he suddenly burst onto the set, sweating profusely, out of breath. Almost in tears, he cried out to the director, to the cast, to anyone, “I’m sorry! My alarm didn’t go off!” Someone—perhaps me—asked, “What time was your call?” “Call?” he responded. It was then gently explained that you only come to the studio when called.

The production ended on May 1, 1967, and A Challenge for Robin Hood was trade shown on November 28 at Studio One taking advantage of the Christmas school break, the film was released on the ABC circuit on December 24, to positive reviews. The Kinematograph Weekly (December 2): “Barrie Ingham has a fine presence as Robin Hood”; The Monthly Film Bulletin (January, 1968): “Lively rendering of the familiar legend”; and The New York Times (January 18, 1968): “Excellent. The picture moves with such intelligent speed, in fact, that the fairly modest budget seldom shows.” The film is a lighthearted romp with no pretentions or subplots. Its characters are clearly defined, and Pennington-Richards gave his actors a free hand. Comedy, thrills, and romances are evenly distributed in Hammer’s best Robin Hood.

The Anniversary

Released February 18, 1968 (U.K.), February 7, 1968 (U.S.); 95 minutes; 8505 feet; Technicolor (U.K.), DeLuxe Color (U.S.); a Hammer–7 Arts Film Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Studios, Elstree, England; Director: Roy Ward Baker (replaced Alvin Rakoff); Producer & Screenplay: Jimmy Sangster, based on a play by Bill MacIlwraith; Director of Photography: Harry Waxman; Art Director: Reece Pemberton; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Editor: Peter Weatherly; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Title Music: The New Vaudeville Band; Production Manager: Victor Peck; Assistant Director: Bert Batt; Camera: Gerry Anstiss; Sound Recordist: Les Hammond; Sound Editor: Charles Crafford; Continuity: June Randall; Makeup: George Partleton; Hairdresser: A.G. Scott; Wardrobe: Mary Gibson; Recording Supervisor: A.W. Lumkin; U.K. Certificate: A.

Bette Davis (Mrs. Taggart), Sheila Hancock (Karen Taggart), Jack Hedley (Terry Taggart), James Cossins (Henry Taggart), Elaine Taylor (Shirley Blair), Christian Roberts (Tom Taggart), Timothy Bateson (Mr. Bird), Arnold Diamond (Head Waiter), Albert Shepherd, Ralph Watson (Construction Workers), Sally Jane Spencer (Florist).

Mrs. Taggart (Bette Davis), a domineering matriarch, is celebrating the tenth anniversary of the death of her unloved husband. The eyepatch-sporting Mrs. Taggart has maintained a cruel hold over her grown sons, executives in the Taggart Home Construction company, by learning their weaknesses and using that knowledge to keep them in line. She emotionally blackmails her oldest son, Henry (James Cossins), a transvestite, by threatening him with the law. Terry (Jack Hedley) is determined to emigrate to Canada with his wife Karen (Sheila Hancock) in order to get away. Youngest son Tom (Christian Roberts) shows up with a new fiancée each year and announces his intention to marry his latest, Shirley (Elaine Taylor), who is pregnant.

Bette Davis celebrates in Hammer’s black comedy The Anniversary.

Mrs. Taggart venomously battles with her sons’ women in order to keep iron control. To remind Terry that it was his carelessness with an air rifle that cost her her eye, she leaves her glass eye between the covers of a bed to shock Shirley.

The sons and their lovers all stand up to the insidious Mrs. Taggart, but in the end she plays her final cards, binding her sons and their women even closer to her: She telephones her attorney and authorizes him to begin legal proceedings to collect money from Karen. She then authorizes the solicitor to terminate the service agreement Taggart Home Construction holds with Tom. Admitting that Shirley reminds her of herself, Mrs. Taggart also tells the attorney to authorize a check for £5000 in the bride’s name and speculates how long their marriage will last with Shirley holding the pursestrings.

Before retiring for the night, Mrs. Taggart locks up her deceased husband’s study and remarks that it has been a lovely anniversary after all.

James Carreras bought the rights to Bill MacIlwraith’s black comedy about the ultimate dysfunctional family shortly after its West End opening on April 20, 1966. While the stage version starred Mona Washbourne, Carreras hoped to get Bette Davis for the lead, and producer Jimmy Sangster’s screenplay was sent to her. Jack Hedley, Sheila Hancock, and James Cossins were signed to repeat their stage roles. Filming began on May 1, 1967, with Alvin Rakoff directing—for a week—before Davis demanded that he be replaced. “Rakoff didn’t have the first fundamental knowledge of making a motion picture,” she said in Mother Goddam, “let alone what an actor is all about.” Roy Ward Baker, Davis’ neighbor years before in Malibu, was Rakoff’s “lucky” replacement. “The change,” he said in Starlog, “was all done over one weekend. I didn’t even bother to see any of Rakoff’s footage. I threw it away, and we started fresh Monday morning.” Davis’ next move was to demand that the script be changed, and Baker agreed. “As a play,” he recalled, “it was a kind of slapstick comedy in which the mother set up the jokes for the other characters to crack.” Bette told Jimmy Sangster, “I must be the pivotal figure, and they have to set up the jokes for me to crack. Otherwise, they don’t want me!” The supporting cast were, naturally, concerned that their roles would be sacrificed to appease the star.

Originally set for eight weeks, The Anniversary wrapped on July 22, two weeks over schedule. The premiere was held at the Rialto on January 11, 1968, where the film earned £8000 in its two-week run. The film also did well in general release, which began in February, and made The Kinematograph Weekly’s Top Money Winner’s list. Reviews were mixed, as one would expect for a black comedy. The Sun (January 11): “A frequently funny black comedy”; The Sunday Express (January 11): “Unnerving, yet wickedly funny”; The Daily Telegraph (January 11): “Sloppy and uninvolving”; The New York Post (February): “So exaggerated that it shatters the credibility needed to be effective satire”; and Variety (January 24): “A vehicle for the extravagant tantrums of Bette Davis.”

As annoying off camera as on?

Sadly, her tantrums were not confined to the screen. Sheila Hancock recalled in Charles Higham’s Bette, “I wasn’t prepared for Miss Davis’ great entourage and for the fawning attitude it had towards her. I was shocked when the producer gave us a lecture saying that Miss Davis liked to be treated with great adulation.”

This was a far cry from Peter Cushing’s queuing behind an electrician in the Bray lunch line, and the fawning was hardly worth the trouble.

Released April 14, 1968 (U.K.), May 1, 1968 (U.S.); 101 minutes; Technicolor (U.K.), DeLuxe Color (U.S.); a Hammer–7 Arts Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Studios, England, and on location in Monte Carlo and Southern Spain; Director: Cliff Owen; Producer: Aida Young; Screenplay: Peter O’Donnell, based on the characters created by H. Rider Haggard; Music and Special Musical Effects: Mario Nascimbene; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Saxophone Solo: Tubby Hayes; Director of Photography: Wolf Suschitzky; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Production Designer: Lionel Couch; Costume Designer: Carl Tomo; Production Manager: Dennis Bertera; Editor: Raymond Poulton; Assistant Director: Terence Clegg; Camera: Ray Sturgess; Sound Recordist: Bill Rowe; Sound Editors: Roy Hyde, Jack Knight; Continuity: Phyllis Townshend; Makeup: Michael Morris; Hair Stylist: Mervyn Medalie; Wardrobe: Rosemary Burrows; Special Effects: Bob Cuff; Ritual Sequences Designer: Andrew Low; Recording Director: A.W. Lumkin; U.K. Certificate: A; MPAA Rating: G.

John Richardson (Killikrates), Olinka Berova (Carol), Edward Judd (Dr. Philip Smith), Colin Blakely (George Carter), Jill Melford (Sheila Carter), George Sewell (Captain Harry), Andre Morell (Kassim), Noel Willman (Za-Tor), Derek Godfrey (Men-Hari), Daniele Noel (Sharna), Gerald Lawson (The Seer), Derrick Sherwin (No. 1), William Lyon Brown (Magus), Charles O’Rourke (Servant), Zohra Segal (Putri), Christine Pockett (Dancer), Dervis Ward (Lorry Driver).

While dazedly wandering on the coast of Southern France, a young woman named Carol (Olinka Berova) is plagued by hallucinatory voices calling her “Ayesha.” A truck overtakes her and the driver (Dervis Ward) offers her a lift. When the driver tries to attack her, Carol flees. The driver pursues her through the woods but is run over by his own truck when it mysteriously slips into gear and careens toward the struggling pair. Carol seems unaffected by what has happened.

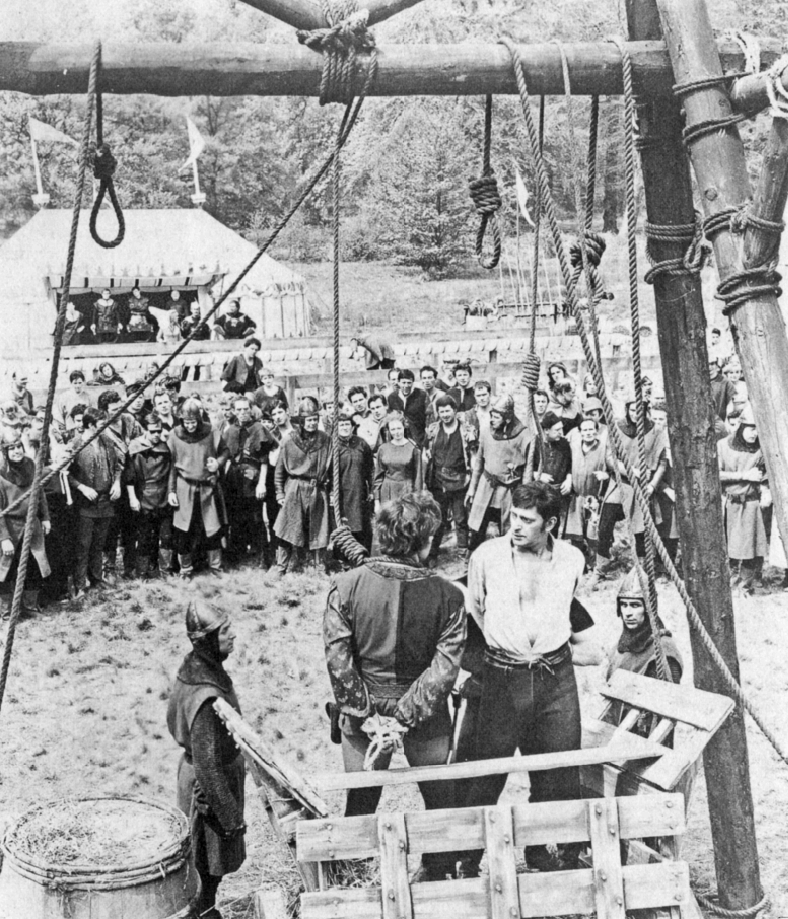

Top: Men-Hari (Derek Godfrey) and fellow citizens of the city of Kuma await the arrival of their reincarnated queen in The Vengeance of She. Bottom: Killikrates (John Richardson) believes he has found his immortal Ayesha (Olinka Berova) in The Vengeance of She.

Carol arrives at Monte Carlo and stows aboard a yacht bound for North Africa. On board she meets Dr. Philip Smith (Edward Judd), a psychiatrist who senses that some compelling force is pulling the tormented girl toward the East. Upon reaching Haifa, Carol flees into the desert and falls into the clutches of a pair of Arabs. Philip, who has followed, rescues her and decides to accompany Carol to her unknown destination.

A totally unnecessary sequel.

When they eventually reach the lost city of Kuma, Carol is greeted as the reincarnation of Queen Ayesha (She), the beloved of King Killikrates (John Richardson). After Philip has been imprisoned in one of the palace chambers, he is visited by Za-Tor (Noel Willman), the leader of a secret sect, who reveals that Killikrates has promised his High Priest, Men-Hari (Derek Godfrey), the secret of immortality if he can bring back Ayesha. Hypnotized by Men-Hari into believing that she is the lost queen, Carol prepares to enter the sacred flames that will render her immortal.

Philip, released by Za-Tor, persuades Killikrates that he had been betrayed and the king kills the villainous Men-Hari. Then, longing to join Ayesha, Killikrates walks into the flames. Carol and Philip watch in horror as Killikrates ages before their eyes and crumbles to dust.

Moments after Carol and Philip make their way safely out of Kuma, the dying Za-Tor invokes the gods of light to destroy the city. There is a gigantic explosion and all that is left of Kuma is rubble and ashes.

Hammer had planned a sequel to She within three months of its completion, but there was no further word until July, 1965. It was then announced that Ursula Andress had been signed to star in Ayesha—Daughter of She, but the picture was not on Hammer’s 1965 schedule. In January, 1966, a brief mention appeared in the trades about The Return of She, but Andress’ contract had expired, and so did Hammer’s plans. A new title, Vengeance of She, appeared in June, 1967, with, supposedly, Susan Denberg slated to star. She was dropped in favor of Andress look-alike Olinka Berova, who had eleven movies to her credit in Czechoslovakia. Filming began in Monte Carlo on June 26, 1967, with Hammer newcomer Cliff Owen directing. Aida Young, an associate producer on three previous Hammer films, took full production responsibilities, as she would for five future pictures for the company. Six weeks of interiors followed at Elstree, and on August 19, the unit left for more location work at Almeria, Spain. The production ended on September 16, and while the film was being edited, Hammer and 20th Century–Fox began negotiations for the co-production of a television series. Fox was to assume 75 percent of the financing for the tentatively titled Tales of the Unknown.

Vengeance of She was trade shown on March 21, 1968, at the Warner-Pathe. It went into general release on April 14, disappointing audiences and critics alike. The Sun (April 5): “A remarkably dull load of hokum”; The Morning Star (April 6): “A cheap and gaudy piece of mumbo-jumbo”; The Kinematograph Weekly (March 20): “The plot is a load of melodramatic rubbish”; and The Monthly Film Bulletin (May): “The dialogue is literally unspeakable.” The film fared no better in America, and it sank without a trace. The film seemed to exist solely to parade Olinka Berova across the screen and completely wastes it main assets—Andre Morell and Noel Willman. It is hard to believe that a picture with those actors could be this bad. Strangely enough, neither actor worked for Hammer again.

Released July 20, 1968 (U.K.), December, 1968 (U.S.); 95 minutes; Technicolor (U.K.), DeLuxe Color (U.S.); 8584 feet; a Hammer–7 Arts Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Elstree Studios; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay: Richard Matheson, based on Dennis Wheatley’s novel; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Music: James Bernard; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Supervising Art Director: Bernard Robinson; Supervising Editor: Spencer Reeve; Camera Operator: Moray Grant; Sound: A.W. Lumkin; Sound Recordist: Ken Rawkins; Sound Editor: Arthur Cox; Continuity: June Randall; Makeup: Eddie Knight; Hairstyles: Pat McDermott; Wardrobe Supervisor: Rosemary Burrows; Wardrobe: Janet Lucas; Casting: Irene Lamb; Special Effects: Michael Stainer-Hutchins; Choreographer: David Togure; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: G; U.S. Title: The Devil’s Bride.

Christopher Lee (Duc de Richleau), Charles Gray (Mocata), Nike Arrighi (Tanith), Leon Greene (dubbed by Patrick Allen) (Rex Van Ryn), Patrick Moyer (Simon), Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies (The Countess), Sarah Lawson (Marie), Paul Eddington (Richard), Rosalyn Landor (Peggy), Russell Waters (Malin). England, 1920s. The Duc de Richleau

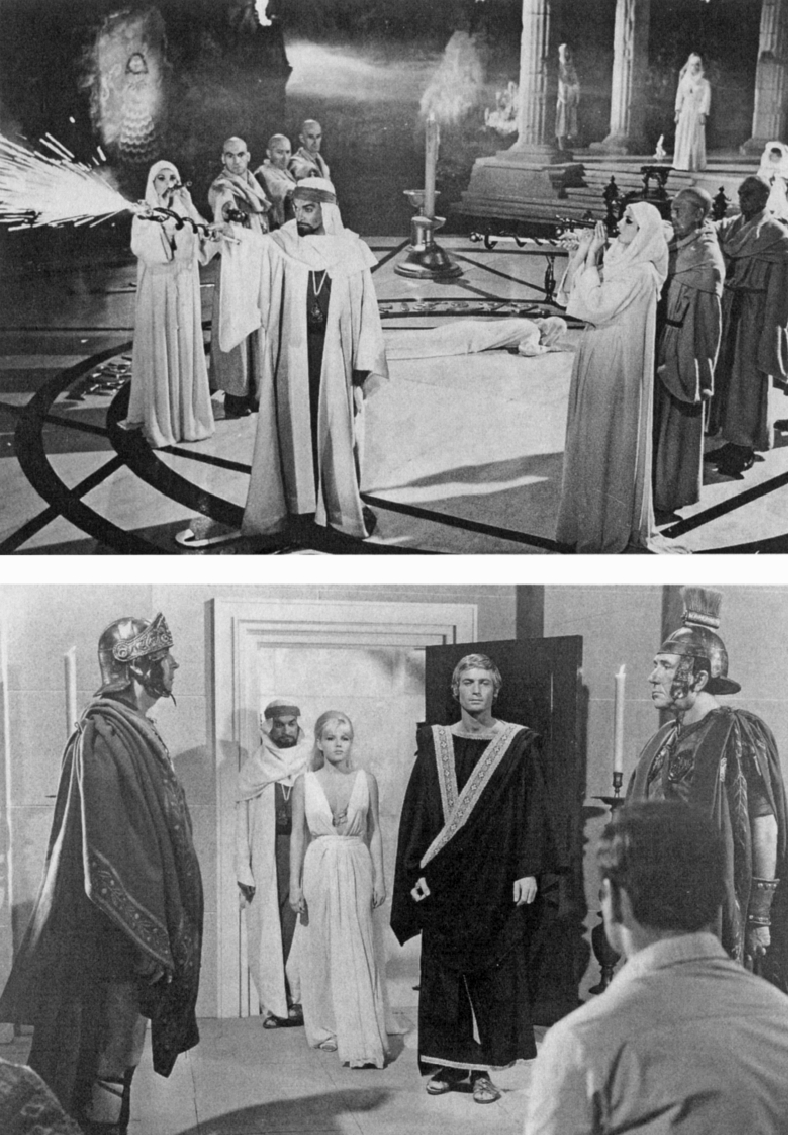

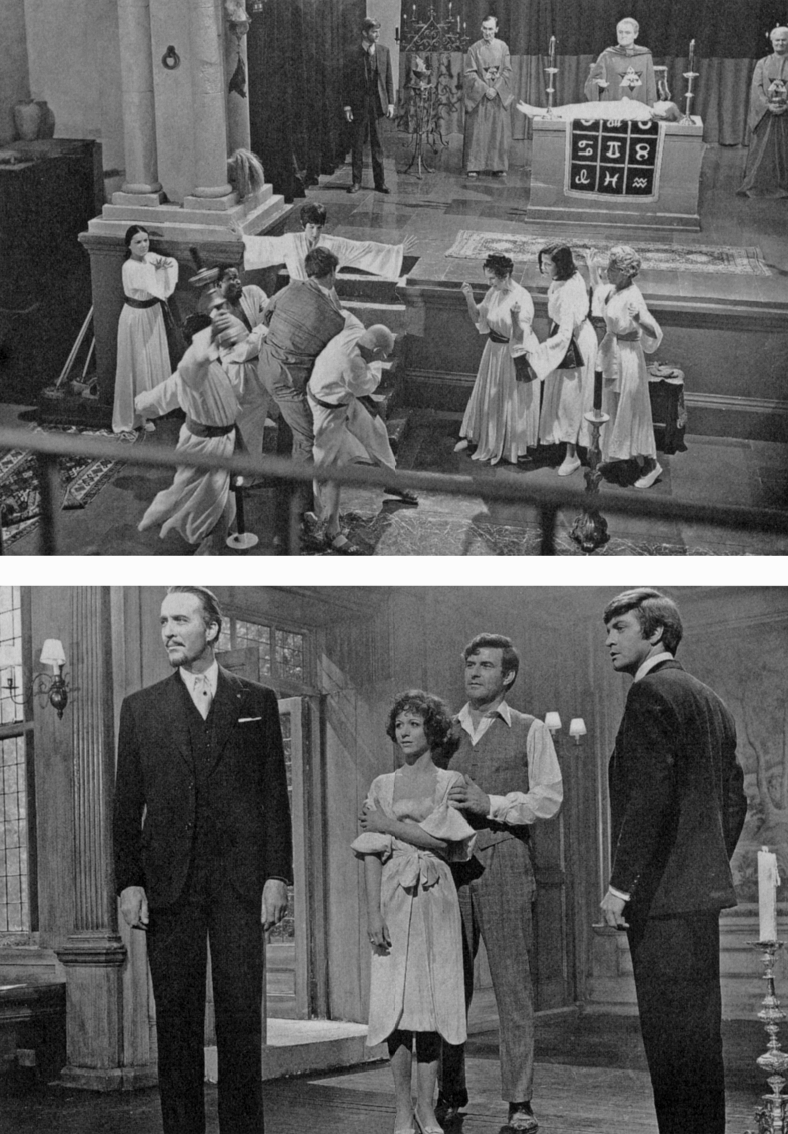

Top: On the set of The Devil Rides Out (note column braces and mop on left side of the stage). Bottom: Christopher Lee, Nike Arrighi, Leon Greene, and Patrick Moyer encounter the ultimate evil in this adaptation of Dennis Wheatley’s exciting novel The Devil Rides Out.

(Christopher Lee) and Rex Van Ryn (Leon Greene) are rebuffed when they visit their friend Simon Aron (Patrick Moyer) by his group of new “friends”—a devil cult headed by Mocata (Charles Gray). After discovering the truth about Mocata’s so-called “astrological society,” the Duc and Rex spirit Simon to de Richleau’s home, but Mocata’s power is too great and he regains control of his minion. When they return to Simon’s house, the Duc and Rex are greeted by a demon. Rex persuades Tanith (Nike Arrighi), a cult member, to go with him to the home of his friends Richard (Paul Eddington) and Marie (Sarah Lawson) Eaton, but Mocata lures her away. Rex follows her to a demonic ceremony in the forest—the conjuring of Satan. Joined by the Duc, he frees Simon and Tanith, and they return to the Eaton’s home.

While the men are away, Mocata arrives and places Marie under a hypnotic spell, broken by the entrance of her child Peggy (Rosalyn Landor). Later, to protect the others from Mocata’s power, Rex takes Tanith from the house. The Duc realizes that Mocata will stop at nothing to return Simon and Tanith to his fold and prepares for the worst by drawing a holy circle on the floor. He, Simon, and the Eatons are attacked by Mocata’s induced horrors—a huge spider and the Angel of Death, which kills Tanith. During the confusion, Peggy is abducted and taken to Mocata’s home. By using a potent ritual, the Duc and Marie destroy the coven and the friends return, unarmed, back at the Eatons’ home—including Tanith. Due to the ritual’s magic, time had been reversed, and Mocata was taken in her place.

Dennis Wheatley was—and still is—Britain’s leading writer of the occult, churning out over fifty best sellers, including The Devil Rides Out (1935). Wheatley took Black Magic quite seriously and warned his readers against even a casual involvement. The Devil Rides Out was the first filming of a Wheatley novel, and he was on the set at Elstree on September 15, 1967. Both he and his wife were impressed after meeting the cast and crew. Oddly, his Lost Continent was being shot by Hammer at the same time.The Kinematograph Weekly (September 23) felt that Wheatley had been “untapped by filmmakers until now because of the vast scope of the adventure stories and the supernatural content of the black magic books.” Hammer was, as usual, on the leading edge—not only with Wheatley but with filming Satanic subjects. Both The Devil Rides Out and The Witches were in production before Rosemary’s Baby, which is usually given “credit” for recreating interest in the occult. Actually, Hammer planned to filmThe Devil Rides Out as early as 1964.

The production began at Elstree on August 7, 1963, and was completed on September 29. After a May 17, 1968, trade show at the Warner-Pathe, the picture premiered at the New Victoria on July 20, and was released on the ABC circuit on July 20. It was well received by the critics—a rare event for Hammer in the sixties. The Daily Express (June 7, 1968): “The manner and period are faithfully reproduced”; The Daily Mirror (June 7): “As flesh crawling stuff it’s not bad”; The Kinematograph Weekly (May 25): “It has moments of chilling appeal”; The Daily Cinema (May 22): “Gripping excitement”; Variety (June 12): “Suspenseful”; and Films and Filming (August, 1968): “Hammer has returned to its original standard.”

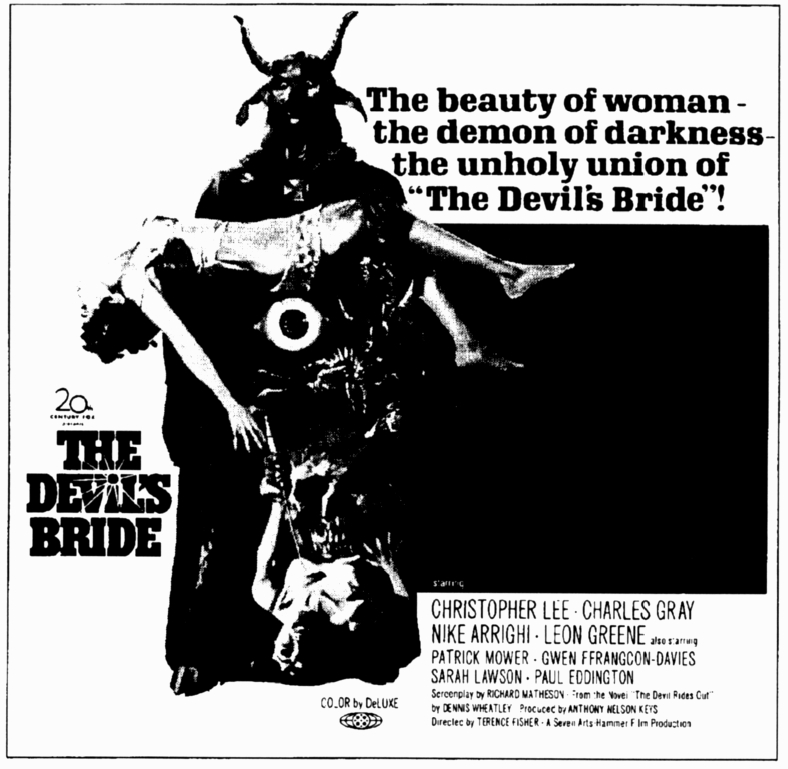

The screen’s first adaptation of a Dennis Wheatley work, The Devil Rides Out was presented in the United States as The Devil’s Bride.

Hammer would produce over thirty more films after this, but only Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed equalled its quality. Christopher Lee was perfectly cast, although purists may have felt he was too young. His stern demeanor usually does not lend itself to heroic roles, but in this case it worked. It is unfortunate that Hammer did not start a de Richleau series—there were certainly enough books, and Lee may have preferred the role to Dracula. This would be his last non–Dracula part for Hammer until Wheatley’s To the Devil—A Daughter (1976). As good as Lee is, the film is “stolen” by Charles Gray’s excellent job as Mocata. His appearances are brief and well-timed—not unlike Lee’s Dracula. The remainder of the cast is fine with former model Nike Arrighi a standout, but Leon Greene is disconcertingly dubbed by Patrick Allen.

Although the film is considered one of Terence Fisher’s best, he had some doubts. “The love angle,” he told Harry Ringel, “was very superficial. I don’t know why, probably my fault. The relationship between Nike Arrighi and Leon Greene never develops as it should have. The film would have been much stronger if it had.” Wheeler Dixon mentions in his study of Fisher that the director was moved by a telegram from Dennis Wheatley. “Saw film yesterday. Heartiest congratulations. Grateful thanks for splendid direction.” Fisher might have felt better about the film if it had not indirectly led to the end of his career. He was hit by a car while crossing a road after a post production session. His broken right leg kept him from directing Dracula as Risen from the Grave (taken over by Freddie Francis), and he would only direct two more films before his retirement in 1972.

The film has only one major flaw—the ordinary special effects. Richard Matheson (May, 1992) told the authors that during an earlier published interview he “spoke out of turn about the direction. There was nothing wrong with Fisher’s directing. I found a few of the actors subpar, Lee and Charles Gray certainly not among them. Some of the effects were a little chintzy, but all in all, it was quite well done.” Most of Hammer’s best films did not rely on special effects, but this one did, and the movie is badly let down. It is hard to take Mocata seriously through his conjuring—it is Gray’s performance that carries across the menace. Bernard Robinson’s sets beautifully recreated England in the 1920s, the antique cars are as good as anyone could see in a museum, and James Bernard’s score adds immeasurably to the tension.

Although the film has its weak spots, mostly caused by the budget, it manages to rise above them and is one of Hammer’s last great horrors.

Released July 27, 1968 (U.K.), June 19, 1968 (U.S.); 98 minutes (U.K.), 83 minutes (U.S.); Technicolor (U.K.), Color by DeLuxe (U.S.); 8830 feet; a Hammer–7 Arts Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), 20th Century–Fox (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Elstree Studios; Director: Michael Carreras; Producer: Michael Carreras; Associate Producer: Peter Manley; Screenplay: Michael Nash, based on Dennis Wheatley’s novel Uncharted Seas; Director of Photography: Paul Beeson; Music: Gerard Schurmann; Music Supervisor: Philip Martell; Songs by: Roy Philips; Sung by: The Pedlars; Production Design: Arthur Lawson; Special Effects: Robert Mattey, Cliff Richardson; Consultant: Arthur Haynaid; Modeller: Arthur Fehr; Editor: Chris Barnes; Camera: Russell Thomson; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Costume Design: Carl Toms; Assistant Director: Dominic Fulford; Continuity: Doreen Scan; Assistant Art Director: Don Picton; Casting: Irene Lamb; Makeup: George Partleton; Hairdresser: Elsie Alder; Wardrobe: Mary Gibson; Sound Editor: Roy Baker; Sound Mixer: Dennis Whitlock; Sound Recordist: A.W. Lumkin; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: G.

Eric Porter (Lansen), Hildegard Knef (Eva), Suzanna Leigh (Unity), Tony Beckley (Harry), Nigel Stock (Webster), Neil McCallum (Hemmings), Benito Carruthers (Ricaldi), Jimmy Hanley (Pat), James Cossins (Chief), Dana Gillespie (Sarah), Victor Maddern (Mate), Reg Lye (Helmsman), Norman Eshley (Jonathon), Michael Ripper (Sea Lawyer), Donald Sumpter (Sparks), Alf Joint (Jason), Charles Houston (Braemar), Shivendra Sinha (Hurri Curri), Darryl Read (El Diablo), Eddie Powell (Inquisitor), Frank Hayden (Sergeant), Mark Heath, Horace James (Men).

A “realistic” set from the indescribable The Lost Continent.

On uncharted seas, Captain Lansen (Eric Porter) is transporting illegal explosives and a motley collection of passengers: Harry (Tony Beckley), a drunken pianist; Dr. Webster (Nigel Stock), who is being sued for malpractice; Unity (Suzanna Leigh), his oversexed daughter; Eva (Hildegard Knef), former mistress of a South American dictator; and Ricaldi (Benito Carruthers), a security agent on her trail. A hurricane is coming, but Lansen ignores First Officer Hemming’s (Neil McCallum) warning. The crew mutinies, and the ship is abandoned. As their lifeboat drifts aimlessly, Webster is eaten by a shark and Ricaldi by an octopus before they miraculously are returned to the ship, now engulfed by intelligent—and hungry—seaweed.

After boarding the ship, they drift into a mysterious sea where countless survivors of previous disasters have gone, finding a land ruled by El Diablo (Darryl Read). With the help of Sarah (Dana Gillespie), Lansen sets the seaweed ablaze, and they escape their captors as the lost continent is destroyed by a volcanic eruption.

Just about everybody was lost on this one!

This was Hammer’s second Dennis Wheatley story, but the company was without a map as it adapted his Uncharted Seas. The film is a stylistic mess, totally absurd, but entertaining in a Plan 9 from Outer Space sort of way. The film was announced in The Kinematograph Weekly (June 17, 1967) as a “large scale action-adventure subject … to be made in the tradition of She and One Million Years B.C., and will take a full year to complete.” Hammer (supposedly) sent a team to London’s Natural History Museum to “consult marine biologists” to ensure accuracy. A month later, The Lost Continent was still being described as a large scale production, and Hammer was still engaged in “research.” The major roles were cast by September 3, 1967, and the only holdup was waiting for The Devil Rides Out to finish at Elstree. The “authentic” monsters were finished in time for an October start.

The Lost Continent ended Hammer’s three-year, seventeen-picture association with 20th Century–Fox. James Carreras told The Kinematograph Weekly (February 24, 1968), “No hard feelings. Hammer ought to get back to its former policy of playing the field.” He expressed his pride in Hammer’s continued independence, finding all of its pre-production costs from their own resources. Under consideration were a quick reunion with Fox, and the re-opening of Bray, for a proposed television series that became Journey to the Unknown for ABC-TV.

When The Lost Continent was released on the ABC circuit on July 27, 1968, audiences were not exactly treated to a “large scale subject” planned the previous year. But even the most negative reviewers grudgingly admitted to being entertained. Films and Filming (August, 1968): “This is one of the most ludicrously enjoyable bad films”; The New York Times (June 20): “Marvelously absurd”; Variety (July 3): “The result is quite a stew.” It’s –difficult to defend something like The Lost Continent—its special effects are not especially special, and they were planned as a major drawing point. But, it is fun.