Released June 8, 1969 (U.K.), February 11, 1970 (U.S.); 97 minutes; Technicolor; 8771 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a Warner Bros.–7 Arts Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Elstree Studios, England; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Anthony Nelson-Keys; Screenplay: Anthony Nelson-Keys, Bert Batt; Music: James Bernard; Music Supervisor: Philip Martell; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Camera: Neil Binney; Editor: Gordon Hales; Production Design: Bernard Robinson; Production Manager: Christopher Neame; Makeup: Eddie Knight; Hairdresser: Pat McDermott; Continuity: Doreen Dearnaley; Sound Supervisor: Tony Lumkin; Assistant Director: Bert Batt; Supervising Editor: James Needs; Sound Recordist: Ken Rawkins; Sound Editor: Don Ranasingher; Construction Manager: Arthur Banks; Wardrobe Mistress: Lotte Slattery; Wardrobe Supervisor: Rosemary Burrows; Publicist: Bob Webb; Special Effects: Studio Locations, Ltd.; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: PG.

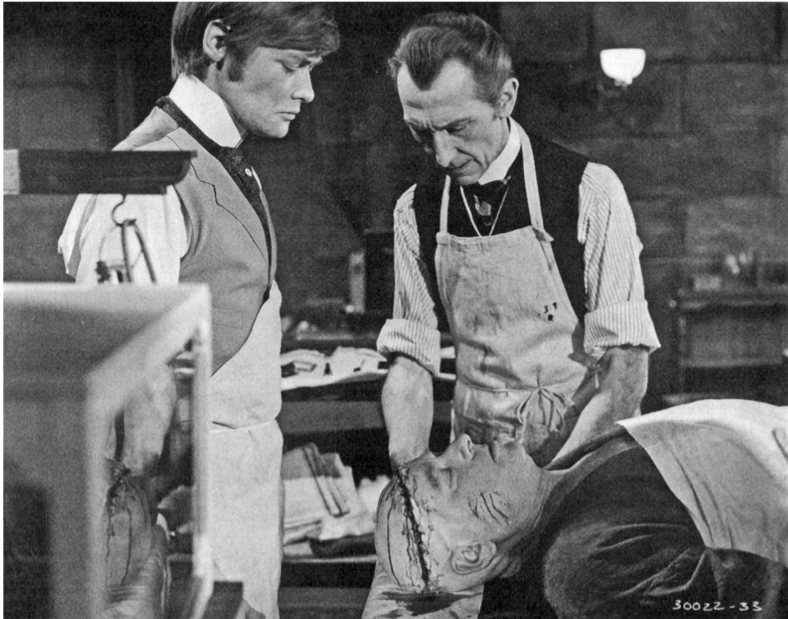

The Baron (Peter Cushing, right) and his unwilling assistant, Karl (Simon Ward), in Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed.

Peter Cushing (Baron Frankenstein), Veronica Carlson (Anna), Freddie Jones (Prof. Richter), Simon Ward (Karl), Thorley Walters (Inspector Frisch), Maxine Audley (Ella Brandt), George Pravda (Brandt), Geoffrey Bayldon (Police Doctor), Colette O’Neil (Mad Woman), Harold Goodwin (Burglar), George Belbin, Norman Shelley, Frank Middlemass, Michael Gover (Guests), Jim Collier (Dr. Heidecke), Alan Surtees, Timothy Davies (Policemen), Peter Copley (Principal).

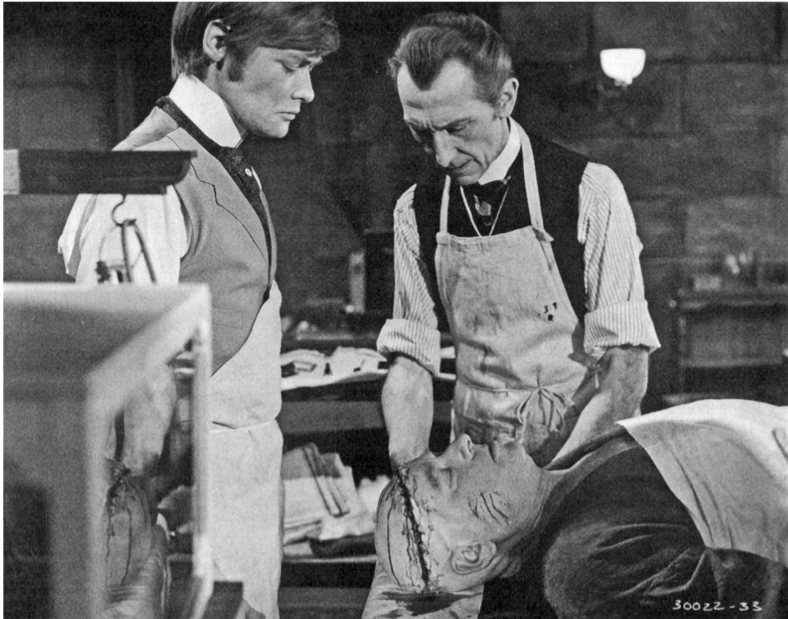

Terence Fisher is about to shout “Action!” in this third take from Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (photo courtesy of Tim Murphy).

After his secret laboratory is discovered by Inspector Frisch (Thorley Walters), Baron Frankenstein (Peter Cushing) is on the run. Calling himself Fenner, he takes a room at Anna Spengler’s (Veronica Carlson) boarding house. Overhearing a conversation between other lodgers, he learns that his colleague, Dr. Brandt (George Pravda), is incarcerated in a nearby asylum. Brandt developed a new transplant technique before going mad, and Frankenstein is determined to get it from him. Anna’s lover Karl (Simon Ward) is a doctor at the asylum and steals drugs to sell to pay Anna’s mother’s medical expenses. Frankenstein blackmails the couple into helping him kidnap Brandt. During their escape, Brandt suffers a heart attack and is near death. The Baron then abducts Dr. Richter (Freddie Jones), another asylum doctor, and plans to transplant Brandt’s brain into his healthy body. With the police—and Mrs. Ella Brandt (Maxine Audley)—in pursuit, Frankenstein and his victims hide in an abandoned house as Brandt/ Richter heals.

After “he” regains consciousness, the terrified Anna misinterprets his actions and stabs him. After “he” staggers away, Frankenstein kills Anna and tracks the creature to Brandt’s house with Karl not far behind. Ella is horrified and rejects the pathetic creature’s plea for understanding. After she leaves, he prepares a trap for Frankenstein with his notes, hidden in a kerosene-soaked room, as bait. As Frankenstein enters the inferno, Karl arrives and the creature shoots him. Clutching the notes, Frankenstein runs from the house but is tackled by the dying Karl. The creature lifts Frankenstein to his shoulders and carries him back into the blazing house.

Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed was the last Hammer film to combine the talents of Peter Cushing, Terence Fisher, James Bernard, and Bernard Robinson. It was also the only Hammer Frankenstein not written by either Jimmy Sangster or Anthony Hinds. Anthony Nelson-Keys was working on Lock Up Your Daughters when Hinds asked if he would like to produce another Frankenstein. “But this time,” Keys recalled in Little Shoppe of Horrors, “Hinds said, ‘You have to write the story.’” Also working on Daughters was Bert Batt, who, in addition to being an assistant director, had done some writing which Keys thought was “extraordinarily good.” Together they worked out an outline which Batt turned into a screenplay unlike anything Hammer had previously produced. In the past, the villain always got his due and the hero triumphed, but in Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, there were no heroes—only villains and victims. Even the pathetic Brandt/Richter creature does “the right thing” only for revenge, and not from any sense of duty. The times were changing, and Hammer was changing with them.

Filming began on January 13, 1969, on the company’s best film of the decade. Terence Fisher specifically asked for Freddie Jones as the film’s nominal “monster.” Like Michael Gwynn’s Karl in The Revenge of Frankenstein, Brandt is far more wronged than wrong. “To lend verisimilitude to a character who awakens to find himself in another body makes a powerful demand upon the actor,” Jones told the authors (March, 1992).

Incredibly, I recall the logical sequence I followed: fearful headache, therefore a desire to touch and perhaps discover some things. On its way up to the head, the hand naturally came into view. Shock!—as the hand was instantly unfamiliar! More spontaneous perfunctory investigation and then, I notice the shiny surface of a kidney-shaped bowl—a mirror! And the truth. I don’t recall any role making a greater demand.

Young Simon Ward had just left the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, and this was his first film. “I just didn’t know what was going on,” he confessed in Screen International (June 4, 1977). “Peter Cushing was absolutely marvellous, and I don’t know what I would have done without him.” Equally in need of his help was Veronica Carlson who, against almost everyone’s wishes, was pushed by James Carreras into performing a rape scene with Cushing. Carreras felt the film needed more sex, and Carlson told the authors (August, 1991) that “I couldn’t refuse to do it. Peter was disgusted with the scene, and he didn’t want to do it. Terence Fisher was very understanding, but it was totally embarrassing and humiliating.” It was also an afterthought and does not fit with the previously shot scenes which it renders false. “It gives my character no credence,” Carlson rightly complained. Fortunately, the scene was cut from American prints. Recently re-inserted by Turner Broadcasting, the scene does little for the film, although it was well acted and directed.

Hammer brings a new look to an old theme.

German ad for Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed.

During the picture’s production, Hammer was the subject of BBC’s Made in Britain, which acknowledged the company’s receiving the Queen’s Award to Industry. “We give the customers what they want,” he said, “and they want to be frightened out of their wits!” Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed wrapped on February 26. Not even a heavy snowfall interfered with additional outside filming as an army of workmen swept the street set so the continuity would not be compromised. The trade show was held at the Warner on May 20, and premiered at the same theatre on the 22nd. After a two-week run (during which it took £4208 and £3175), the movie went into general release on the ABC circuit on June 8. Despite the film’s pessimism and graphic horror, reviews were surprisingly positive. The British Film Institute’s Monthly Film Bulletin (June): “The most spirited Hammer horror in some time”; The Kinematograph Weekly (May 24): “The period atmosphere and lowering settings keep the excitement at a fine active simmer”; Variety (June 11): “There’s nothing tongue in cheek about Fisher’s directing”; and The London Times (May 22): “As nasty as anything I have seen in the cinema for a very long time.”

Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed was Hammer’s last outstanding film, with all concerned at the top of their form. Although set in period, the story caught the negativity of the Vietnam era, and wove in expertly the topicality of drug abuse. It is practically flawless and stands next to Dracula as Hammer’s greatest horror film, but is a difficult film to enjoy. Terence Fisher (Cinefantastique, Vol. 4, No. 3) called it “The one which nobody else seems to care for.” Peter Cushing was never better in a horror movie, and at the 1994 FANEX Hammer Convention in Baltimore, his performance was voted as the best given in a Hammer film.

Released October 26, 1969 (U.K.), March, 1970 (U.S.); 100 minutes; Technicolor; 8999 feet; a Hammer/Warner Bros./7 Arts Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), Warner Bros./7 Arts (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Elstree Studios; Director: Roy Ward Baker; Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Michael Carreras, from a story by Frank Hardman, Gavin Lyall, and Martin Davidson; Director of Photography: Paul Beeson; Art Director: Scott MacGregor; Music: Don Ellis; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Editor: Spencer Reeve; Sound: Roy Hyde; Sound Recordist: Claude Hitchcock; Special Effects: Les Bowie; Production Manager: Hugh Harlow; Choreography: Jo Cook; Assistant Director: Jack Martin; Costumes: Carl Toms; Special Photography: Kit West, Nick Allder; U.K. Certificate: U; MPAA Rating: G.

James Olson (Bill Kemp), Catherina Von Schell (Clementine Taplin), Warren Mitchell (J.J. Hubbard), Adrienne Corri (Liz Murphy), Ori Levy (Karminski), Dudley Foster (Whitsun), Bernard Bresslaw (Harry), Neal McCallum (Space Captain), Michael Ripper, Robert Tayman (Card Players), Sam Kydd (Barman), Keith Bonnard (Junior Customs Officer), Leo Britt (Senior Customs Officer), Carol Cleveland (Hostess), Roy Evans (Workman), Tom Kempinski (Officer), Lew Luton (Immigration Officer), Claire Shenstone (Hotel Clerk), Chrissie Shrimpton (Botigue Attendant), Amber Dean Smith, Simorie Silvera (Hubbard’s Girls).

The year 2021. After decades of space exploration, the glamour is gone for many space heroes, including Bill Kemp (James Olson), who with his sidekick Karminski (Ori Levy) is piloting a rundown ferry ship, the Moon Zero Two. In order to keep flying—against the wishes of Liz Murphy (Adrienne Corri), an antagonistic police chief—Kemp agrees to corral a sapphire asteroid. This will put him closer to J.J. Hubbard (Warren Mitchell), who runs things on the moon. But first, Kemp plans to help Clementine Taplin (Catherina Von Schell) to find her missing brother Wally, who turns up dead. Kemp and Clementine are attacked by Hubbard’s hired guns—he wants the Taplins’ claim as a landing site for the asteroid. Hubbard’s gunslinger Harry (Bernard Bresslaw) kills Liz and forces Kemp and Clementine to land the asteroid. They do—on top of Hubbard’s gang. Clementine now owns the sapphire and Kemp has reclaimed his former status as a hero.

Moon Zero Two is another example of Hammer over-reaching itself. Beginning with She, Hammer became involved in projects that required more money than the company was used to spending. There is nothing wrong with this film that a bigger budget would not have cured. Moon Zero Two was described as a “space western,” meaning that Western clichés were updated to the future—an idea that worked much better in Sean Connery’s Outland (1981). Production began with special effects work on March 8, 1969, and live action shooting started on March 31. Hammer launched the picture with a barrage of publicity and press luncheons, at which James Carreras (Kinematograph Weekly, April 15, 1969) enthused, “Nineteen sixty nine is the year of the moon—everyone’s going there. This lunch is to celebrate Hammer’s and Great Britain’s occupation of the moon.” The production wrapped on June 10, and the company made every effort to link their movie with the American moonshot scheduled for July—the best free advertising available! Unfortunately, the public was far more interested in the real thing.

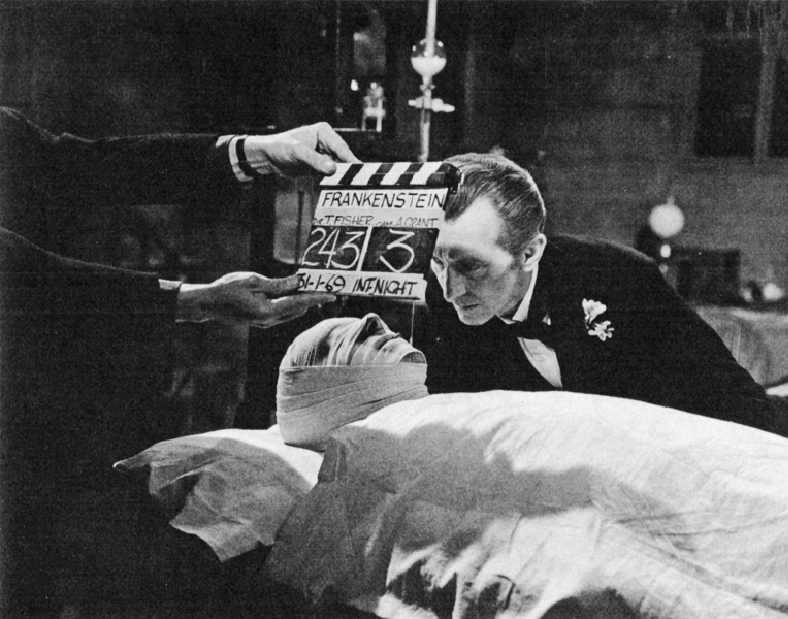

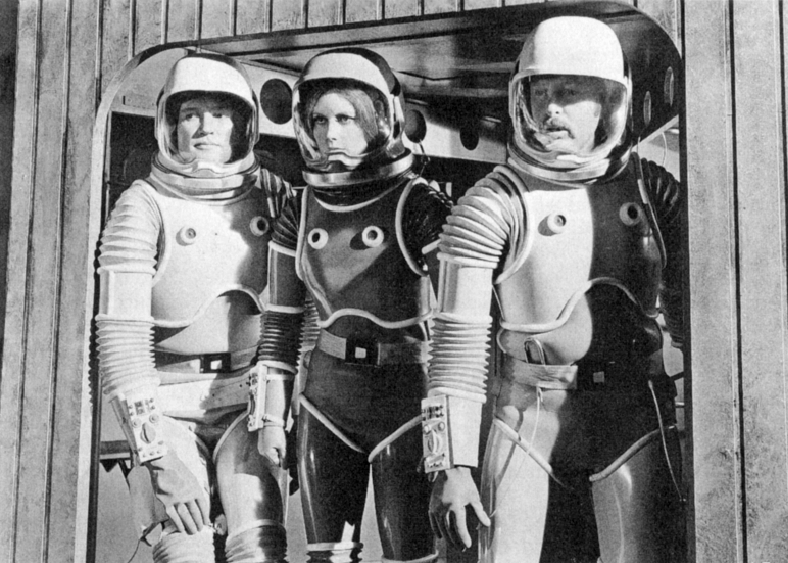

Top: Hammer’s ill-advised “space western,” Moon Zero Two. Bottom: A good idea done badly—and upstaged by NASA.

A special screening was held during the first week of October, followed by an October 8 trade show at the Warner and an October 26 release on the ABC circuit. Carreras predicted in The Kinematograph Weekly (April 5) that Moon Zero Two would be Hammer’s “biggest box office picture ever” and was even planning a sequel, Disaster in Space. Unfortunately, Moon Zero Two was enough of a disaster, as The Kinematograph Weekly (November 8) reported. It was “disappointingly below average in all situations.” The film might have succeeded a few years earlier, but it could not compete with an actual moon landing. Unlike 2001—A Space Odyssey (1968), Moon Zero Two was rooted in a semi-plausible reality which paled before the awesome truth. In short, James Olson was no match for Neil Armstrong.

Roy Ward Baker (Starlog 21), said, “Moon Zero Two was a bad picture. It was hopeless and never got off the ground.” Concerning Michael Carreras, Baker commented, “He’s a delightful man, but he was inclined to take on tasks that were much better left to other people. But, he took on a bit too much. Then, he took on the running of Hammer itself, and he really overstretched himself.” Critics generally agreed with Baker. The London Times (October 16, 1969): “The special effects are none too special”; The Observer (October 19): “As silly a piece of pseudo-science fiction as you could loathe to find”; and The Guardian (October 17): “It’s dreadfully made from start to finish.”

Moon Zero Two was definitely one small step for Hammer.

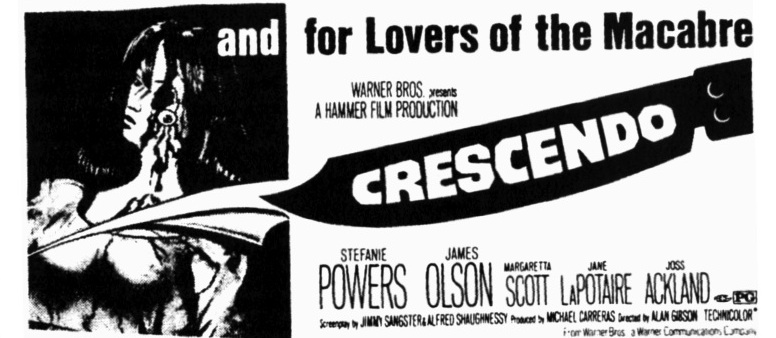

Released June 7, 1970 (U.K.), November, 1972 (U.S.); 95 minutes (U.K.), 83 minutes (U.S.); Technicolor (U.K.); a Hammer/Warner Bros./7 Arts Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a Warner Bros./7 Arts Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Studios, Elstree, England, and on location in France; Director: Alan Gibson; Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Jimmy Sangster, Alfred Shaughnessy; Director of Photography: Paul Beeson; Art Director: Scott MacGregor; Editor: Chris Barnes; Music: Malcolm Williamson; Music Performed by: The London Symphony Orchestra; Piano Soloist: Clive Lithgoe; Saxophone Soloist: Tubby Hayes; Production Manager: Hugh Harlow; Assistant Art Director: Don Picton; Assistant Director: Jack Martin; Camera: John Wilbolt; Continuity: Lillian Lee; Construction Manager: Arthur Banks; Makeup: Stella Morris; Hairdresser: Ivy Emmerton; Wardrobe: Jackie Breed; Property Buyer: Ron Baker; Set Dresser: Freda Pearson; Sound Mixer: Claude Hitchcock; Dubbing Mixer: Len Abbott; Sound Editor: Ron Hyde; Recording Supervisor: A.W. Lumkin; Sound: RCA Sound System; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: PG.

Stefanie Powers (Susan Roberts), James Olson (Georges/Jacques), Margaretta Scott (Danielle Ryman), Jane Lapotaire (Lillianne), Joss Ackland (Carter), Kirsten Betts (Catherine).

Is it Georges or Jacques? Stefanie Powers fights for her life in Crescendo.

Susan Roberts (Stefanie Powers), an American music teacher, comes to France to write a biography on the life of composer Henry Ryman. She has been invited to stay at the home of Ryman’s widow (Margaretta Scott), who lives in a country manor house with her wheelchair-bound son Georges (James Olson). Georges is addicted to pain-killing heroin which is administered by Lillianne (Jane Lapotaire), the maid, who seduces Georges behind closed doors, using the needed injection as a bribe to force his cooperation. As the painkiller takes effect, Georges slips into a deep sleep and relives once again a terrifying nightmare.

Hammer strikes a discordant note.

Susan comes across a photo of a young woman who looks like herself. Mrs. Ryman explains that her name was Catherine and that her son was in love with her. However, after his accident, she left him. Susan later realizes that Mrs. Ryman may be trying to make her into another “Catherine” to torment Georges.

Mysterious happenings ensue, like piano music in the night and the murder of Lillianne, who is stabbed to death in the swimming pool by an unseen assassin. Georges suffers a painful attack, and this time Susan administers the heroin he needs. Mrs. Ryman tells Susan that in France, not only is the drug addict subject to imprisonment, but also anyone administering the drug. Mrs. Ryman agrees not to press the issue if Susan marries her son.

Susan finds that Georges has a mad twin brother, Jacques (also James Olson), who is responsible for killing Lillianne and who thinks Susan is Catherine. Jacques stalks her throughout the estate and is about to shoot her when Mrs. Ryman appears and saves her, shooting Jacques in the back. Slipping out through the front gate, Susan runs for her life, leaving behind Georges and his mother, who had hatched an insane plot to carry on the Ryman musical legacy through the birth of Jacques’ child with Susan.

Crescendo was Hammer’s first psycho-thriller since The Nanny four years earlier, but the picture was not worth the wait. Filming began on July 14, 1969, turning one of Elstree’s largest sound stages into a French Provincial estate, complete with swimming pool and gardens. Directing was former actor Alan Gibson, who was given his first feature after his involvement with several BBC series. As he would further prove with Dracula A.D. 1972, Gibson had little understanding of what Hammer films were all about. After wrapping at Elstree on August 23, the production moved to the Camargue for location work. Crescendo was trade shown at Studio One on May 7, 1970, and premiered the same day at the New Victoria supporting Taste the Blood of Dracula. The pair went into general release on June 7, and the package was voted onto Kinematograph Weekly’s Top Moneywinner’s list. This was totally on the strength of the Dracula picture, as Crescendo had practically nothing to offer. Critics were united in their condemnation of this thrilless thriller. Today’s Cinema (May 22, 1970): “A run-of-the-mill suspense story”; New York (December 4, 1972): “It’s all clunking nonsense”; Newsday: “Witless—a reject from the ABC Movie of the Week”; and The New York Daily News: “Disintegrates under the direction of Alan Gibson.”

Not much could have improved Crescendo, which was critically injured from its inception. It had all been done before, and better. Stefanie Powers and James Olson give their expected professional performances, but they are not nearly enough. Powers remarked (Warner Bros. press release), “There is no Dracula or Frankenstein in the cast.” Maybe there should have been.

Taste the Blood of Dracula

Released June, 1970 (U.K.), September 16, 1970 (U.S.); 95 minutes; Technicolor; a Hammer Film Production; a Warner-Pathe Release (U.K.), a Warner Bros. Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Studios, Elstree, and on location in Hertfordshire, and Highgate Cemetery, London; Director: Peter Sasdy; Producer: Aida Young; Screenplay: John Elder, based on the character created by Bram Stoker; Director of Photography: Arthur Grant; Art Director: Scott MacGregor; Music: James Bernard; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Special Effects: Brian Johncock; Production Manager: Christopher Sutton; Assistant Director: Derek Whitehurst; Editor: Chris Barnes; Sound Recordist: Ron Barron; Sound Editor: Roy Hyde; Construction Manager: Arthur Banks; Makeup Supervisor: Gerry Fletcher; Continuity: Geraldine Lawton; Wardrobe: Brian Owen-Smith; Dubbing Mixer: Dennis Whitlock; Hairdressing Supervisor: Mary Bredin; Recording Supervisor: Tony Lumkin; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: GP.

Lord Courtley (Ralph Bates) calls upon the powers of darkness to resurrect Count Dracula in Taste the Blood of Dracula.

Christopher Lee (Dracula), Geoffrey Keen (William Hargood), Gwen Watford (Martha Hargood), Linda Hayden (Alice Hargood), Peter Sallis (Samuel Paxton), Isla Blair (Lucy Paxton), John Carson (Jonathan Secker), Martin Jarvis (Jeremy Secker), Anthony Corlan (Paul Paxton), Ralph Bates (Lord Courtley), Roy Kinnear (Weller), Shirley Jaffee (Betty, Hargood’s Maid), Michael Ripper (Cobb), Russell Hunter (Felix), Reginald Barrett (Vicar), Keith Marsh (Father), Peter May (Son), Madeline Smith (Dolly), Lai Ling (Chinese Girl), Malaika Martin (Snake Girl).

Christopher Lee and the Goat of Mendes from Taste the Blood of Dracula.

Stranded near Castle Dracula, Weller (Roy Kinnear), an antiques dealer, witnesses Dracula’s death by impalement on a crucifix and retrieves the Count’s ring, cloak, and a vial of blood.

Outside London, Hargood (Geoffrey Keen), Secker (John Carson), and Paxton (Peter Sallis) live outwardly as family men, but indulge themselves in monthly visits to a brothel. One night they meet Lord Courtley (Ralph Bates), a decadent who challenges them to sell their souls in exchange for “ultimate pleasure.” He takes them to Weller’s shop where they purchase Dracula’s remains. They meet in an abandoned chapel where Courtley mixes Dracula’s blood with his own, but the men refuse to drink it. Courtley takes his own dare and is convulsed in agony. As Courtley lies dying, Hargood returns home to his wife (Gwen Watford) and daughter Alice (Linda Hayden). Meanwhile, Courtley’s corpse metamorphoses into Dracula (Christopher Lee), who swears to avenge his servant’s death.

Hargood, who is hypocritically protective of Alice, forbids her relationship with Paxton’s son Paul (Anthony Corlan). His abusive behavior leads her to an encounter with Dracula, who uses her to destroy the three families, as she kills her father with a shovel and lures Paul’s sister Lucy (Isla Blair) into vampirism. When Paxton and Secker return to the chapel, they find Lucy’s vampiric corpse, but Paxton wounds Secker before he can stake her. He realizes his error too late—she kills her own father, as does Jeremy Secker (Martin Jarvis), under her vampiric spell.

Paul learns that Dracula is the cause of the deaths and sets out to save Alice. He traps Dracula in the chapel where he has substituted Christian symbols for the blasphemous ones on the altar. Dracula tries to escape through a window, but is overcome by the symbols of righteousness and falls to his death, releasing Alice from his power.

Due to the success of Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, Hammer planned to produce a sequel per year as long as the market demanded it. However, Anthony “John Elder” Hinds was now under pressure to come up with the new variations on a threadbare theme. Following the previous pattern, Hinds dropped Dracula into a situation that did not really warrant his inclusion and treated the Count as an afterthought. Assigned to direct Taste the Blood of Dracula was Peter Sasdy, a veteran of over 100 television shows. Sasdy had taught drama and journalism at Budapest University, but left Hungary during the 1956 revolution. He continued to teach in Britain before breaking into television. “One of the most pleasing things about this particular Dracula subject,” he said (Kinematograph Weekly, December 13, 1969), “is that for the first time (in a Hammer film), the setting is in London. This means the characters are not strange people in a foreign land—they are the sort of people whom audiences in Britain and America are going to recognize more readily.” One must certainly question Sasdy’s opinion about the “normality” of the Hargood family.

The beginning of the end of a great series.

Filming began on October 27, 1969, and due to Sasdy’s television experience, he averaged six minutes of screen time per day, finishing on December 5. “The basic advantage which television gives you,” he said, “is the ability to work at speed.” A trade show was held on May 6, 1970, at Studio One, and the film premiered at the New Victoria. Taste the Blood of Dracula went into general release in the U.K. on June 7 and in American on September 16, to mixed reviews. The London Times (May 10): “A surprise—well played and directed”; The Monthly Bulletin (May): “Absolutely routine”; Today’s Cinema (May 15): “Not as eerie as previous episodes”; New York Magazine (November 2): “Honors the tradition and kind of adds to it”; and the New York Post (October 29): “Directed and acted with the usual stylishness of Hammer Films.”

Christopher Lee, again, seemed to do a Dracula picture under protest. He said in his fan club journal, “On November 3, I start what I hope will positively be my last film for Hammer. As usual, words fail me as indeed they will also do in the film.” Lee later changed his mind, telling interviewer Bill Kelley, “I liked certain elements of the storyline; and apart from the absence of Peter Cushing, we had the best cast of any of the Dracula films.”

Ralph Bates, fresh from the BBC’s Caligula, made his splashy film debut as Lord Courtley in the first of his five Hammer films. The company was looking for young actors to assume the roles that would eventually be vacated by Cushing and Lee, and Bates seemed to be a perfect choice. But Hammer’s demise came faster than anyone could have imagined, and replacing the two stars never became an issue.

Hammer’s fifth Dracula was a huge financial success, making The Kinematograph Weekly’s “Top Moneymakers” list and was the last film in the series to have any merit. Despite demoting Dracula to a minor character, the film has much to recommend it, especially James Bernard’s outstanding score. The cast is above average, and Peter Sasdy managed to get across the perversion without resorting to the excesses that would soon become Hammer’s hallmark. Using Dracula, the ultimate in decadence, as the agent to destroy Victorian hypocrisy was one of the last clever ideas in the series.