Released October 4, 1970 (U.K.); 91 minutes (U.K.), 89 minutes (U.S.); Technicolor; 8188 feet; a Hammer Film Production; Released through MGM/EMI (U.K.), American International (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Elstree Studios; Director: Roy Ward Baker; Producers: Harry Fine, Michael Style; Screenplay: Tudor Gates, based on J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s novel Carmilla; Director of Photography: Moray Grant; Music: Harry Robinson; Music Supervisor: Philip Martell; Editor: James Needs; Art Director: Scott MacGregor: Production Manager: Tom Sachs; Sound: Roy Hyde; Costumes: Brian Box; Recording Supervisor: Tony Lumkin; Continuity: Betty Harley; Makeup: Tom Smith; Hairdresser: Pearl Tipaldi; Wardrobe: Laura Nightingale; Construction Manager: Bill Greene; Dubbing Mixer: Dennis Whitlock; Camera: Neil Binney; Sound Recordist: Claude Hitchcock; Assistant Director: Derek Whitehurst; U.K. Rating: X, MPAA Rating: R.

Ingrid Pitt (Mircalla/Marcilla/Carmilla), Pippa Steele (Laura), Madeline Smith (Emma), Peter Cushing (General Von Spielsdorf), Dawn Addams (The Countess), Kate O’Mara (Madam Perrodot), Douglas Wilmer (Baron Hartog), Jon Finch (Carl Ebbhart), Kirsten Betts (First Vampire), John Forbes-Robinson (Man in Black), Harvey Hall (Renton), Ferdy Mayne (Doctor), George Cole (Roger), Janey Key (Gretchen), Charles Farrell (Kurt).

Baron Hartog (Douglas Wilmer) attempts to destroy the vampiric Karnstein family after they take his sister, but one of them escapes. Later, General Spielsdorf (Peter Cushing), while hosting a lavish party, greets the Countess (Dawn Addams), and her daughter, Marcilla (Ingrid Pitt). The Countess leaves unexpectedly, and the General offers to shelter Marcilla. She and Laura (Pippa Steele), the General’s niece, become friendly—and more. After coming between Laura and Carl (Jon Finch), her fiancé, Marcilla seduces her and takes her blood, eventually killing her.

Now calling herself Carmilla, Marcilla reappears at Roger Morton’s (George Cole) estate and, as she has done so often before, “befriends” a beautiful young girl. Emma Morton (Madeline Smith) soon falls under Carmilla’s spell, as does Madam Perrodot (Kate O’Mara). Renton (Harvey Hall), a servant, suspects the worst and contacts his traveling master, who joins forces with Baron Hartog and the General. The vampire hunters, now aware that Carmilla is a Karnstein, track her to her castle where the General drives stake through her heart and cuts off her head.

The Karnsteins are now thought to be destroyed, but a mysterious Man in Black (John Forbes-Robinson) has been watching.

The Vampire Lovers was based on J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1871 Carmilla, which served as the basis for Vampyr (1931), Blood and Roses (1960), and Terror in the Crypt (1963), among others. Film censorship and the public’s taste had changed so much by 1970 that the lesbianism hinted at in earlier versions could be shown with little reticence. Harry Fine told author Bruce Hallenbeck (Little Shoppe of Horrors 4): “With great difficulty, I managed to find a copy of LeFanu’s original story after finding stills from a stage adaptation of Carmilla.” He approached Tudor Gates to write a treatment which was sent to James Carreras, who was entranced by the title. “The Vampire Lovers!,” he said. “I think I can set it up right away.” Fine and Michael Style finalized an agreement with Hammer on November 25, 1969, and a month later, Carreras secured financing through American International Pictures. Former AIP head Samuel Z. Arkoff told the authors (May, 1992),

Behind-the-scenes on The Vampire Lovers—Ingrid Pitt primps as Peter Cushing looks on (photo courtesy of Ted Okuda).

We went to England in 1964 to do the second half of our Poe series, and Roger Corman got tired of it all. We stayed in England because of lower production costs, and might have approached Hammer, but we didn’t. We had always done them ourselves. We finally joined together with The Vampire Lovers—which Jimmy sold to us over a meal! Hammer always had a great style for their horror films. They were fundamentally adult, not geared toward teenagers. Jimmy never gave ground to teenagers!

The Vampire Lovers began production on January 19, 1970, at Elstree, with location work at the Moor Park golf course. Filming ended on March 4, with a September 3 trade show at Metro House followed by an October 4 premiere at the New Victoria. Paired with Angels from Hell on the ABC circuit, the package broke several attendance records and made The Kinematograph Weekly’s Top Moneymaker list for 1970. One might wonder if the crowds were attracted by the film’s horror or lesbian sex. “The permissiveness of the sixties,” Harry Fine said (Little Shoppe of Horrors 4), “finally caught up with Hammer at the end of the decade.” As so often happened in these early days of film nudity, those involved found it necessary to justify their involvement. “If the film requires nudity,” Ingrid Pitt told Al Taylor (Filmfax 15), “I’m not against it. The nudity was there to make a point.” She told the authors (July, 1994), “Sex and nudity are very natural for human beings and nothing to be ashamed of.” Pitt enjoyed her scenes with Peter Cushing, despite his cutting off her head! “It was a bit unnerving,” she said, “to have my family see stills of Peter holding my severed head.” Unlike Pitt’s casual attitude towards the nudity, Madeline Smith (Bizarre 6) felt differently. “I hated doing it. I would never do it now.” Oddly, Valerie Gaunt (in Dracula) managed to be far more sensuous while wearing far more clothing. The Vampire Lovers is a bit obvious and far too earnest in its attempt to titillate.

Reviews were kinder than Hammer may have expected: The Sunday Times (September 6, 1970): “The days of aesthetic horror seem remote”; The Kinematograph Weekly (September 5): “This spooky nonsense is really very good fun on its own level of entertainment”; and The New York Times (February 4, 1971): “A departure from a hackneyed bloody norm.”

Peter Cushing double-checks his diction in this behind-the-scenes shot from The Vampire Lovers (photo courtesy of Tim Murphy).

Ingrid Pitt dominates this retelling of the Carmilla story.

Although The Vampire Lovers is one of Hammer’s best seventies films, it cannot stand with the company’s initial horror efforts, proving that it takes more than nudity and blood to grab an audience. Despite a good cast and crisp direction from Roy Ward Baker, production values were down, and Hammer continued to move farther away from the days of The Hound of the Baskervilles.

Horror of Frankenstein

Released November 8, 1970 (U.K.); 95 minutes; Technicolor (U.K.), DeLuxe Color (U.S.); 8589 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Anglo-EMI Release (U.K.), a Continental Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Elstree Studios; Director: Jimmy Sangster; Producer: Jimmy Sangster; Screenplay: Jimmy Sangster, Jeremy Burnham; Director of Photography: Moray Grant; Music: Malcolm Williamson; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Art Director: Scott MacGregor; Production Manager: Tom Sachs; Editor: Chris Barnes; Assistant Director: Derek Whitehurst; Sound Recordist: Claude Hitchcock; Sound Editor: Terry Poulton; Camera Operator: Neil Binney; Continuity: Betty Harley; Makeup: Tom Smith; Hairdresser: Pearl Tipaldi; Wardrobe: Laura Nightingale; Construction Manager: Arthur Banks; Recording Director: Tony Lumkin; Dubbing Mixer: Bill Powe; U.K. Rating: X, MPAA Rating: R.

Ralph Bates (Victor Frankenstein), Kate O’Mara (Alys), Veronica Carlson (Elizabeth), Dennis Price (Bodysnatcher), Joan Rice (His Wife), Graham James (Wilhelm), Bernard Archard (Professor), Jon Finch (Officer), Dave Prowse (Monster).

Young, handsome, intelligent, and amoral, Victor Frankenstein (Ralph Bates) murders his father and inherits his title, wealth, and mistress Alys (Kate O’Mara). After a brief stay at Vienna University, he returns home with Wilhelm (Graham James), bent on creating a being from the dead. With parts supplied by the local bodysnatcher (Dennis Price) and his wife (Joan Rice), he proceeds, but Wilhelm has misgivings and is conveniently electrocuted.

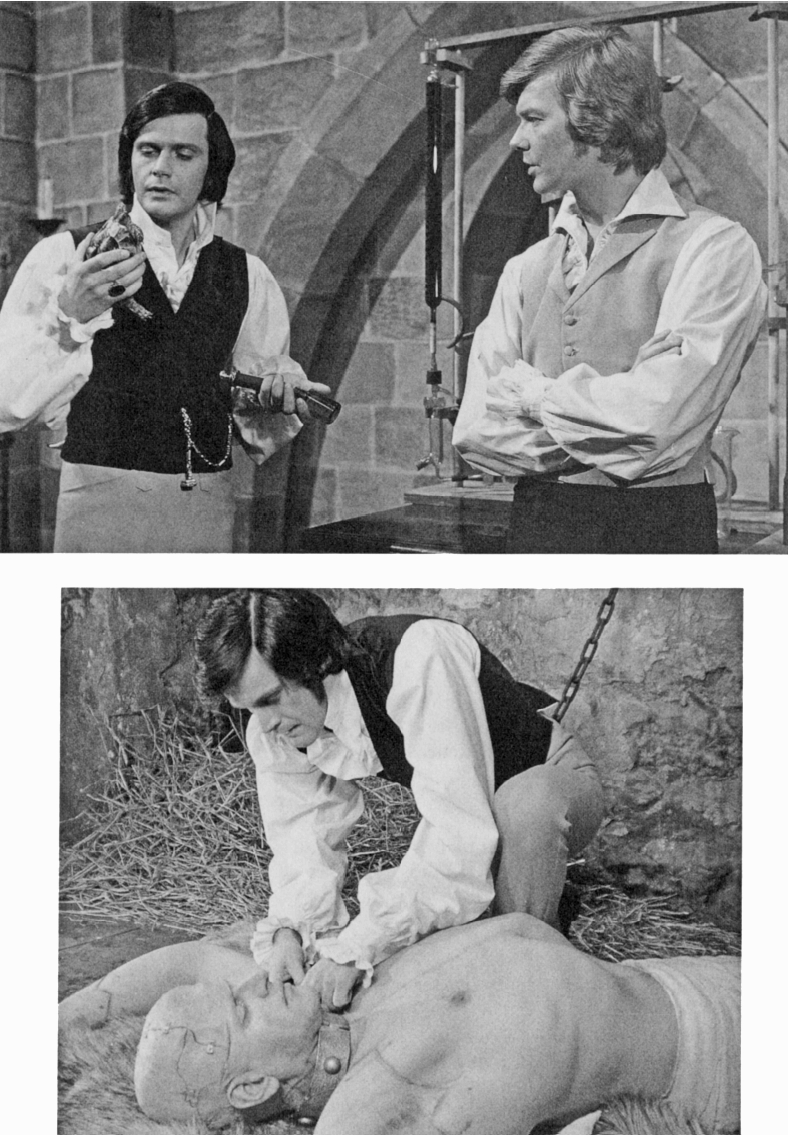

Top: Ralph Bates (left) and Graham James in Jimmy Sangster’s tongue-in-cheek Horror of Frankenstein. Bottom: Frankenstein (Ralph Bates) secures the restraints on his uncooperative creation (Dave Prowse) in Horror of Frankenstein.

Victor murders a neighboring professor (Bernard Archard) for his brain, but his “code of conduct as a gentleman” forces him to shelter his victim’s daughter Elizabeth (Veronica Carlson), who has loved him since childhood. As he transplants the brain into his man-made man, the bodysnatcher—whoops!—drops it, but Victor pushes on after disposing of the blunderer in an acid tank. A chance bolt of lightning brings the creature (Dave Prowse) to life after which he escapes into the forest. After capturing his creation, Victor silences the jealous Alys and the nosy wife of the body snatcher, courtesy of the monster.

A long way from The Curse of Frankenstein.

The police (led by Jon Finch) arrive, bringing with them a child who claims to have seen a monster. The Baron has hidden his creature in an empty acid vat, but not for long; the child accidentally releases the acid, destroying the monster and freeing Victor of any charges against him.

Jimmy Sangster described the picture to the authors as “The one nobody liked.” While it is difficult to defend the film on any level, it does qualify as a “guilty pleasure” and, if seen in the right mood, is quite amusing. After establishing itself as a “horror” specialist by remaking the Universal classics, Hammer’s next logical step was to make sequels to its own movies. But, by 1970, this was beginning to wear thin, and Hammer found itself remaking its own remake!

Jimmy Sangster said (Fangoria 10), “Hammer first told me that they were going to remake The Curse of Frankenstein and wanted me to write the script, but I turned the assignment down. Then they offered to let me produce, but again I said no. When I told them I might be interested if they would let me direct as well, Hammer said that I could. Hammer wanted to do a straight remake, but I thought it would work better as a satire. That idea was ultimately a mistake.” Befitting Sangster’s approach, Peter Cushing was never considered to star. Chosen as his replacement was Ralph Bates, who had recently scored in Taste the Blood of Dracula. “Purists” seldom include Bates or the film in discussions of Hammer’s Frankenstein series, and the film is an entertaining “one—off” and nothing more.

Since Hammer never concentrated on the monster character, there was never a problem in replacing any actor in the role. Their five previous Frankenstein movies had five different monsters played by five different performers. Dave Prowse’s casting disturbed no one because, except for Freddie Jones, all of the previous monsters were played by “unknowns.” Prowse, 6'7" and 260 pounds, was a former British weightlifting champion (1962–64). He told the authors (May, 1993),

It was a lot less formal working for Hammer than for other companies. They had their own stable of actors and crews, and one got to know everyone. I’d seen earlier Hammer movies and, after getting involved in the acting scene, I went to their Wardour Street office. “Would you be interested in me doing one of your Frankensteins?” I asked. Well! I got thrown out of the office! They asked me to leave! The next time I went back was four to five years later—when they signed me for the monster. I’ve done all sorts of movies—worked with Stanley Kubrick, comedies, James Bond, Star Wars—but I don’t think I’ve ever had so much fun or worked in such a pleasant atmosphere as I did with Hammer.

Since Jimmy Sangster was fulfilling three roles, he found himself in an unusual situation. “Writers are never welcome on the set,” he told the authors. “Anywhere. In my case, I was also the producer and the director. I still was not welcome on the set!”

Ralph Bates had no illusions about the role or about replacing its originator. “It’s nice to be asked to play such a famous role,” Bates said in the EMI pressbook, “although people are already asking me if I shall play it in subsequent films and am I afraid of being typecast. I just don’t know. Peter Cushing played the role five times, and I do not consider him typecast. Peter is a very comforting example to me.”

Veronica Carlson, after two excellent roles opposite Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, was not enthralled with the film but enjoyed working with the people. She told the authors (July, 1992):

Peter took it very seriously. Christopher Lee took it seriously, too, and you have to respect that. Neither Ralph nor Jimmy took it seriously. They had a jolly good laugh! Some of the lines, well, you couldn’t take them seriously, could you? If I had my choice, I’d prefer the serious. But, either way, I was working with great people. I think Hammer wanted to see if a “young Frankenstein” could work. If they could reintroduce the character and get more mileage out of him. Maybe they realized it wasn’t as successful as the traditional ones that everybody loved. As for my character, she certainly wasn’t as substantial as Anna in my previous Frankenstein film! I did quite a bit to help publicize the film—radio, TV, public appearances. The crew in this—and all the Hammer films—was wonderful. It was just like family. There was no tension, no aggravation. It was just happy! Everyone did their job well, got on with each other very well. They all made me feel very special. You couldn’t hope for a nicer group of people to work for!

Horror of Frankenstein went into production on March 16, 1970, concluding on April 29. Reviews, following the October 15 trade show at Metro House, were more positive than one would expect. The Express (October 30): “Synthetic blood and tongue in cheek horror”; The New York Times (May 18, 1971): “The first hour is not only painless, but also fun. The screenplay is as bright as could be”; Variety (October 21, 1970): “Lighthearted.”

The picture certainly did not do Hammer or Frankenstein much good, but what can one say about a movie in which a severed hand gives the finger when charged with electricity?

Released November 8, 1970 (U.K.), December 23, 1970 (U.S.); 94 minutes, Original Running Time: 96 minutes; Technicolor; a Hammer Film Production; an Anglo-EMI Release (U.K.), an American Continental (Levitt-Pickman) Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Elstree Studios, England; Director: Roy Ward Baker; Producer: Aida Young; Screenplay: John Elder, based on Dracula by: Bram Stoker; Director of Photography: Moray Grant; Art Director: Scott MacGregor; Music: James Bernard; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Special Effects: Roger Dickens, Brian Johncock; Assistant Director: Derek Whitehurst; Editor: James Needs; Construction Manager: Arthur Banks; Makeup: Wally Schneidermann; Makeup Assistant: Heather Nurse; Sound Editor: Roy Hyde; Dubbing Mixer: Dennis Whitlock; Sound Recordist: Ron Barron; Recording Supervisor: Tony Lumkim; Production Manager: Tom Sachs; Continuity: Betty Harley; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: R.

Christopher Lee (Dracula), Jenny Hanley (Sarah Framsen), Dennis Waterman (Simon Carlson), Patrick Troughton (Klove), Christopher Matthews (Paul Carlson), Anoushka Hempel (Tania), Wendy Hamilton (Julie), Michael Gwynn (Priest), Delia Lindsay (Alice), Bobb Todd (Burgomeister), Michael Ripper (Landlord), Toke Townley (Elderly Wagonmaster), David Lealand, Richard Durden (Officers), Morris Bush (Farmer), Margot Boht (Landlord’s Wife).

Dracula (Christopher Lee), revived once again, renews his reign of terror, killing a village girl. A mob of townsmen led by the local innkeeper (Michael Ripper) storms the castle, manhandling servant Klove (Patrick Troughton) and setting fire to the structure. But during the men’s absence from town, Dracula’s army of bats attacks and kills their wives and children.

Christopher Lee in Scars of Dracula.

In nearby Klinenburg, Sarah Framsen’s (Jenny Hanley) birthday is celebrated by Simon (Dennis Waterman) and his brother Paul (Christopher Matthews). The Burgomeister’s servants arrive in search of Paul, who compromised the officials’ daughter. Paul escapes, and after an involved series of events, he finds himself a guest of the Count at Castle Dracula. Paul beds Tania (Anoushka Hempel), one of Dracula’s vampire brides, but just as she is about to sink her fangs into his throat, Dracula appears and stabs the girl to death. Paul is made a prisoner.

Simon and Sarah follow Paul’s trail to the Castle and Dracula invites them to spend the night. As Sarah sleeps she is approached by Dracula, but is saved by the cross around her neck. Dracula orders Klove to remove it, but the lovestruck Klove refuses to obey.

The next morning, Klove warns Simon about Dracula and urges him to take Sarah away. Simon and Sarah make it back to the village where Simon tries to enlist the aid of the villagers to find Paul. They refuse, but the priest (Michael Gwynn) offers his assistance. En route to Castle Dracula, the priest loses his resolve and Simon continues alone. He finds Dracula in his coffin and positions his wooden stake but the vampire’s powers, even in sleep, stay Simon’s hand.

Back in town, the doors of the chapel suddenly swing open and Sarah and the priest are attacked by a bat who swoops down on the priest, killing him. As Sarah rushes toward the Castle, Simon finds Paul’s body impaled on a metal hook.

Paul (Christopher Matthews) romances Tania (Anoushka Hempel) and is about to realize his mistake in Scars of Dracula.

Dracula tries to place Sarah under his hypnotic spell but Klove warns her in time and she holds off the vampire with her cross. The vampire flings Klove off a cliff. Simon impales Dracula with a metal spike, but it misses his heart. Dracula pulls out the spike and is leveling it at Simon when a bolt of lightning strikes it, setting fire to Dracula’s cloak. Simon and Sarah watch as fire consumes Dracula and he topples from the precipice.

By the time Scars of Dracula began production on May 7, 1970, the series was showing hints of burnout that this picture would confirm. Although audiences were still attracted, they were growing weary of the rehashed themes and Christopher Lee’s limited screen time. So was Lee, who said (The Films of Christopher Lee), “Scars of Dracula was the weakest and most unconvincing of the Dracula stories. Instead of writing a story around the character, they wrote a story and fit the character into it. A really bad film in my opinion.” He added (Photoplay, March, 1973), “What I really object to is the gratuitous violence packaged into films as a deliberate policy to appeal to the sadistic in people.”

Roy Ward Baker was wisely hesitant to direct, but not wise enough to resist. “I’d been asked to do Dracula or Frankenstein before, but I always declined, saying politely that I didn’t think I knew anything about horror pictures,” he told Little Shoppe of Horrors. “Violence is, I think, a question of taste and a question of style,” he added.

“When I made Scars, films were becoming increasingly violent, so it was expected by the audience, and Hammer was trying to keep up to date.” One of the few things Baker found to be proud of about the film was a scene out of Stoker’s novel shot for the first time. “I realized,” Baker said (Fangoria 36), “when I re-read Dracula, that there was that gripping description of Dracula climbing down the tower wall, crawling down face first. That to me is the magic of Dracula, part of his fatal fascination. So I filmed that.”

The beginning of the end.

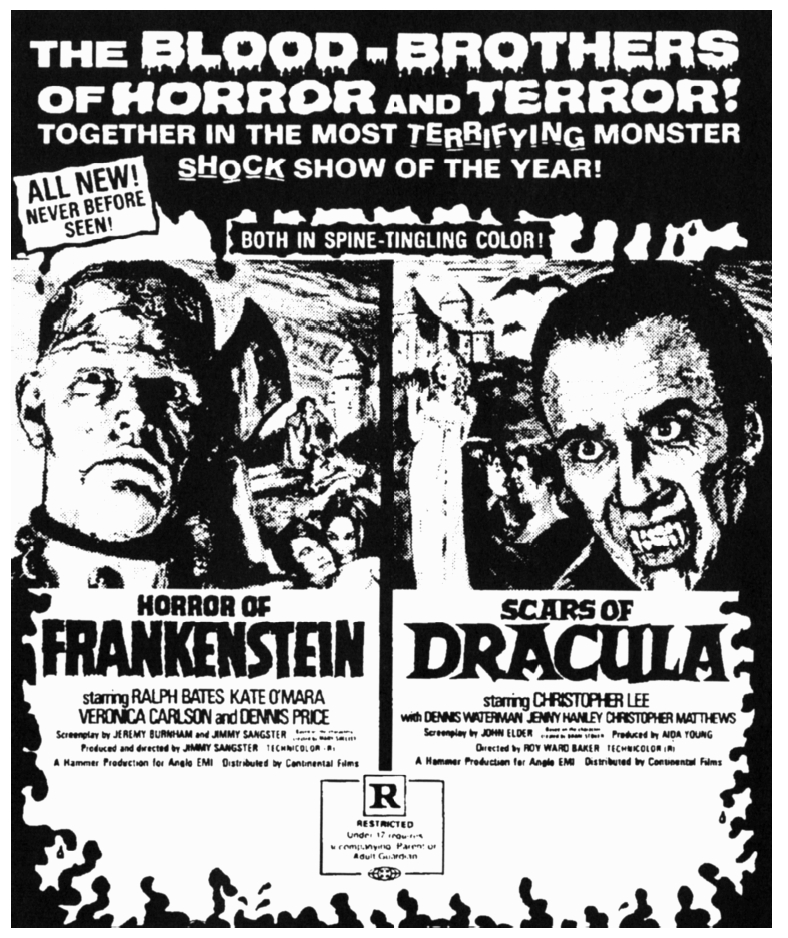

Scars of Dracula and co-feature Horror of Frankenstein were part of a multi-picture deal with Associated British Picture Corporation. James Carreras and Bernard Delfont’s agreement marked the first time in over a decade that a Hammer film was totally financed in Britain. “With one hundred percent British finance,” Carreras said (Today’s Cinema, March 17, 1970), “the world receipts will come direct to Britain.” Each film was budgeted at under £200,000, and both were shot at Elstree. Scars of Dracula ended production on June 23, 1970, and was trade shown on October 23 at Metro House. Oddly, the film premiered on the same day at the New Victoria. The pair did respectable business following a November 8 release on the ABC circuit, but reviewers were unimpressed. Today’s Cinema (October 23, 1970): “I fear the Count must have been drinking blood of the wrong group; otherwise, he would never stoop so low as to stab a woman to death or burn a disobedient servant with a red hot sword”; and The New York Times (June 18): “It’s garish, gory junk.”

Other than James Bernard’s typically outstanding score, Scars of Dracula has little to recommend it. The sets look cheap, the photography is muddy, the young leads are miscast, and Christopher Lee looks more uninterested than ever before. The “plot”—which drops Dracula into the middle of another story in which he does not belong—is awash in unappetizing sex and violence. The film is totally lacking in artistry, and any comparison to the company’s 1957 classic would be unkind. Combined with its Frankenstein co-feature, Scars of Dracula was a sad indication of the direction Hammer was taking in the seventies.

Released April 18, 1971 (U.K.), September, 1971 (U.S.); 95 minutes; Technicolor; a Hammer Film Production; a Columbia Release; filmed on location in Southwest Africa in the Namib Desert; Director: Don Chaffey; Producer & Screenplay: Michael Carreras; Director of Photography: Vincent Cox; Production Designer: John Stoll; Editor: Chris Barnes; Music: Mario Nascimbene; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Art Directors: Roy Taylor, Josie MacAvin; Makeup: Bill Lodge; Special Effects: Syd Pearson; Stunts Arranged by: Frank Hayden: Sound Editors: Roy Hyde, Terry Poulton, John Streeter, Ken Barker; Wardrobe: Rosemary Burrows, Roy Ponting; Makeup: Bill Lodge; Hairstyles: Jeanette Freeman; Production Manager: Jack Martin; Assistant Director: Ferdinand Fairfax: Second Unit Photography: Ray Sturgess; Lighting: Mole Richardson; Second Assistant Director: Simon Peterson; Continuity: Lolly Walder; Assistant Art Directors: Josie McAlvin, Roy Taylor; Location Management: Sun Safaris; Technical Advisor: Adrien Boshner; Stills Cameraman: Albert Clarke; Casting Director: James Liggat; Special Effects: Sid Person; Animals: Uwe D. Schulz; U.K. Certificate: A; MPAA Rating: GP.

A film best forgotten! The abysmal prehistoric drama Creatures the World Forgot.

Julie Ege (Nala), Brian O’Shaughnessy (Mak), Tony Bonner (Toomak), Robert John (Rool), Sue Wilson (Noo), Rosalie Crutchley (Old Crone), Marcia Fox (Mute Girl), Gerard Bonthuys (Young Toomak), Josje Kiesouw (Young Mute Girl), Don Leonard (Old Leader), Beverly Blake, Doon Baide (Young Lovers), Frank Hayden (Murderer), Rosita Moulan (Dancer), Fred Scott (Marauder Leader), Ken Hare (Fair Tribe Leader), Derek Ward (Hunter), Hans Kiesouw (Young Rool), Leo Payne (Old Tribal Artist), Tamsin Millard, Christine Hudson (Rock Women), Heinke Thater, Cheryl Stewardson, Trudy Inns, Samantha Bates, Debbie Aubrey-Smith (Rock Girls), Joan Boshier (Rock Widow), Audrey Allen (Rock Mother), Vera P. Crosdale, Mildred Johnston, Lilian M. Nowag (Old Rock Women), Jose Rozendo, Jose Manuel, Mark Russell, Dick Swain, Alwyn Van Der Merwe, Manuel Neto, Mike Dickman (Rock Men).

In prehistoric times, a volcanic eruption destroys the encampment of the Rock People. The chief (Don Leonard), trapped under a fallen boulder, is killed by his own son (Frank Hayden), who smashes his head with a rock. He later challenges his own brother Mak (Brian O’Shaughnessy) for the right to rule the tribe. The two men fight, and Mak kills his brother with a spear.

Now the Rock Tribe’s chief, Mak leads his people across the desert, seeking a new land. Along the way they encounter the Fair Tribe. Mak and the chief of the Fair Tribe (Ken Hare) are prepared to fight until they see their own children playing peacefully together.

Mak is offered, Noo (Sue Wilson), one of the young women of the Fair Tribe, by the leader. Mak, Noo and the Rock People continue on the search and find a fertile valley where they make their new home.

Noo dies giving birth to twin sons. Years later, Toomak (Tony Bonner) is good and his brother Rool (Robert John) is evil, and the two compete for a mute cave girl (Marcia Fox). When Rool tries to rape the girl, she flees and is captured by the leader (Fred Scott) of another tribe. Toomak and his warriors follow the abductors to their camp and defeat them in a pitched battle. Toomak claims the dead chief’s daughter Nala (Julie Ege) as his mate.

Mak is attacked by a wildebeest and, dying, names Toomak his heir. Rool challenges his brother’s right to rule but is crippled and bested by Toomak in battle. Toomak, Nala and some of his warriors abandon the tribe and set off to find a new colony. Knowing that he will never have the respect of his people while Toomak lives, Rool and his followers track Toomak to his camp and carry off Nala. Toomak follows his brother alone.

Unknown to either man, the mute girl follows Toomak and arrives to find the brothers once again locked in combat. As Rool raises his knife to kill Toomak, she stabs Rool, who falls from a precipice.

This, the last film in Hammer’s “prehistoric trilogy,” is best left forgotten itself. Spurred on by the success of One Million Years B.C. and When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth, Hammer apparently forgot that dinosaurs had been the lure of the first two pictures. Producer/writer Michael Carreras left London in March, 1970, to scout locations in South West Africa and covered nearly 12,000 square miles until concentrating on the Namib Desert. He then checked on hotel accommodations, got government permission to film in the desert, hired a safari company to provide on-site facilities, and consulted with the curator of the Museum of Man and Science. It is sad that all this effort produced such a mediocre picture. While Carreras was toiling in Africa, his father busied himself with a more enjoyable job—finding the “sex symbol of the seventies” in a contest sponsored by Hammer and Columbia. From over 3,000 candidates, the winner was Julie Ege, a beautiful Norwegian non-actress. “The moment Julie Ege walked through my door,” Carreras said (Columbia press release), “we knew our search was ended. She had the same utterly feminine, earthy, sexy quality as Raquel Welch.” The only thing missing was talent, as director Don Chaffey soon found out.

The film audiences would like to forget!

Filmed entirely on location, Creatures the World Forgot began production on July 1, 1970, with an eight week schedule that dragged on until October. A trade show was held on March 19, 1971, and it premiered at the New Victoria on March 28, where it took an excellent £2,959 in the first week. Carried by audience expectations and great advertising, Creatures the World Forgot packed in crowds after its general release on April 18, but word-of-mouth soon caught up. Offering semi-nude women in lieu of dinosaurs, action, and suspense, this is one of Hammer’s worst pictures, as duly noted by the critics. The Daily Express (March 3, 1971): “What we get here is a lot of hairy chaps dressed in bits of fur rushing about bashing each other over the head with rocks, and numerous ladies without even rudimentary brassieres”; and The Monthly Film Bulletin (May): “A feeble excuse for arbitrary sadism and brutality.” The movie is absolute torture to sit through, and is made even worse by its being completely lacking in humor—unless one finds mediocrity funny.

Released January 17, 1971 (U.K.), September, 1971 (U.S.); 95 minutes; Technicolor; 8574 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Associated British Picture Corp. Release (U.K.), an American Continental Films (Levitt-Pickman) Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Studios, Elstree, England; Director: Jimmy Sangster; Producers: Harry Fine, Michael Style; Screenplay: Tudor Gates, based on the characters created by: J. Sheridan Le Fanu; Director of Photography: David Muir; Art Director: Don Mingaye; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Assistant Director: David Bracknell; Editor: Spencer Reeve; Costumes: Laura Nightingale; Production Manager: Tom Sachs; Camera: Chic Antiss; Continuity:

Betty Harley; Sound: Ron Barron; Hairdresser: Pearl Tipaldi; Makeup: George Blackler; Music: Harry Robinson; Song: “Strange Love,” sung by Tracy, lyrics by Frank Godwin; Boom Operator: John Hall; Construction Manager: Bill Green; Recording Director: Tony Lumkin; Dubbing Mixer: Len Abbott; Choreographer: Bobbie McMannis; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: R.

Ralph Bates (Giles Barton), Barbara Jefford (Countess Karnstein/Heritzen), Suzanna Leigh (Janet Playfair), Michael Johnson (Richard LeStrange), Yutte Stensgaard (Mircalla/Carmilla), Mike Raven (Count Karnstein/Dr. Froheim), Helen Christie (Miss Simpson), David Healy (Raymond Pelley), Michael Brennan (Landlord), Pippa Steele (Susan Pelley), Luan Peters (Trudi), Christopher Cunningham (Coachman), Judy Matheson (Amanda McBride), Eric Chitty (Prof. Hertz), Christopher Neame (Hans), Harvey Hall (Inspector Heinrich), Caryl Little (Isabel Courtney), Jack Melford (The Bishop), Erica Beale, Jackie Leapman, Melita Clarke, Patricia Warner, Christine Smith, Vivienne Chandler, Sue Longhurst, Melinda Churcher (School Girls).

Every 40 years the vampiric Karnstein family returns to terrorize the village sitting in the shadow of Karnstein castle. Richard LeStrange (Michael Johnson), a writer of horror stories, arrives to research a book on the Karnsteins and visits the Castle where he meets Giles Barton (Ralph Bates), schoolmaster of a nearby girls’ school. At the school, LeStrange meets the principal, Miss Simpson (Helen Christie), and gym instructor Janet Playfair (Suzanna Leigh). LeStrange is attracted to a new student, Mircalla (Yutte Stensgaard), who arrives with her aunt Countess Heritzen (Barbara Jefford). That night at the local inn, after a serving girl dies suddenly (with puncture wounds on her throat), LeStrange runs into Biggs, the school’s incoming English Literature teacher, an unpublished writer who admires LeStrange’s work. In order to take Biggs’ place at the school (and be close to Mircalla), LeStrange suggests they collaborate on a novel and pays his expenses for a research trip. Lying to Miss Simpson that Biggs is laid up with a broken leg, LeStrange gets the job.

Unusual goings-on ensue as LeStrange realizes that Barton is obsessed with the Karnsteins and Barton finds the body of murdered student Susan (Pippa Steele) and hides it in an abandoned well. Barton knows that Mircalla is actually the vampiress Carmilla, restored to life and youth with the blood of another recently murdered girl. Barton meets her in the castle ruins and begs her to make him her undead slave. When his blood-drained body is later found, the Countess’ personal physician Dr. Froheim (Mike Raven)—actually Count Karnstein—lies that he died of a heart attack.

LeStrange realizes that Mircalla is actually Carmilla but makes love to her anyway. Meanwhile, Police Inspector Heinrich (Harvey Hall) has learned of Susan’s disappearance and, discovering the well, lowers himself by rope into its depths. He discovers her body but as he climbs up, the rope is cut and he falls to his death. Janet, who is in love with LeStrange, tries to enlist his help, but LeStrange, who loves Mircalla, ignores her pleas. Mircalla later attempts to attack Janet, but the teacher is saved by the crucifix around her neck.

Susan’s father, Mr. Pelley (David Healy), arrives with Professor Hertz (Eric Chitty) to look into his daughter’s death. The Countess tries to convince them that Susan died a suicide but Pelley and Hertz soon hear the locals rumbling about vampires at large. They later join a mob of villagers in a march on Karnstein Castle. When the mob sets fire to the edifice, LeStrange rushes inside to try to save Mircalla. Count Karnstein orders her to destroy him, and under his power, she closes in menacingly, but a fiery beam drops from the ceiling and impales her. Pelley rushes in and saves LeStrange just before the ceiling crashes down upon the vampires.

Lust for a Vampire is one of the few Hammer horrors to have nothing to recommend it. The film was a low point for the company and is embarrassing—or should be—for all concerned, including the audience. Part of the trilogy of Karnstein pictures, it glorified the worst excesses of its predecessor, The Vampire Lovers, while lacking any of that film’s positives. Although Peter Cushing was scheduled to star and withdrew due to his wife’s illness, it is doubtful that even he could have elevated the movie to an acceptable level. Screenwriter Tudor Gates told Randy Palmer (Fangoria 40), “Peter is an actor of great stature, and I think this was one thing that caused Lust for a Vampire not to be the picture it could have been. Of course, when Peter Cushing canceled, I re-tailored that part of the script to suit Ralph Bates who was hired to replace him.” Poor Bates came in at the last minute to rescue the film due to his good nature. “I did it,” he said (Bizarre 3), “as a favor to Peter and Jimmy Sangster. I thought it was a tasteless film, and I regret having anything to do with it. But again, Jim is a close, close friend, and so is Peter, so as a friend, I was happy to get them out of a very unhappy situation.”

Teachers Giles Barton (Ralph Bates, left) and Richard LeStrange (Michael Johnson) are both in love with the same student in Hammer’s disastrous Lust for a Vampire.

Sangster also had his regrets. “Terry Fisher was supposed to direct Lust for a Vampire,” he said (Fangoria 10). “Suddenly, Terry broke a leg, and Hammer was right up the proverbial creek. I was on the lot, and they asked me if I’d like to do it. Feeling rather flush having just finished directing my first picture, I said, ‘Yes, sure.’” He had only one week to prepare before the film’s start on July 6, 1970. Saddled with a supporting cast of non-actors (Yutte Stensgaard, Mike Raven), the tongue-in-cheek approach taken was the only way out. The production ended on August 18, and, on the same day, James Carreras signed an agreement with Associated British to make nine movies over the next three years. Associated British would finance the films and provide space at Elstree, with Anglo EMI to handle the domestic releases. It was up to Hammer to find overseas distributors or, in some cases, not. Due to this and other arrangements, Bray became expendable, mainly since Hammer had not used it since 1966. James Carreras estimated its value to be £250,000, but the company would have to split any profits from a sale with Columbia and EMI.

Lust for a Vampire was trade shown on December 8, 1970, at Metro House, and was released on January 17, 1971, on the ABC circuit. Reviewers were justifiably dismissive. The Kinematograph Weekly (December 19, 1970): “Fairly routine vampire stuff, using the well-worn props”; and Variety (September 15): “Tepid horror film of interest to the least discriminating of audiences.” The film’s combination of nudity, lesbianism, gore, bad acting, and a ludicrous theme song added up to something no one needed to see.

Garbage!

Released February 14, 1971 (U.K.), October, 1972 (U.S.); 93 minutes; Eastman Color (U.K.), DeLuxe Color (U.S.); a Hammer Film Production; a Rank Organization Release (U.K.), a 20th Century–Fox Release (U.S.); filmed at Pinewood Studios, England; Director: Peter Sasdy; Producer: Alexander Paal; Screenplay: Jeremy Paul, based on a story by: Alexander Paal, Peter Sasdy, and an idea by Gabriel Ronay; Director of Photography: Ken Talbot; Art Director: Philip Harrison; Music: Harry Robinson; Music Supervisor: Philip Martell; Production Manager: Christopher Sutton; Assistant Director: Ariel Levy; Camera: Ken Withers; Costumes: Raymond Hughes; Editor: Henry Richardson; Makeup: Tom Smith; Sound Mixer: Kevin Sutton; Special Effects: Bert Luxford; Sound: Al Streeter, Ken Barker; Choreography: Mia Nardi; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: R.

Ingrid Pitt (Countess Elizabeth Bathory), Nigel Green (Captain Dobi), Sandor Eles (Imre Toth), Maurice Denham (Master Fabio), Patience Collier (Julie), Lesley Anne Down (Ilona), Peter Jeffrey (Captain Balogh), Jessie Evans (Rosa), Andrea Lawrence (Ziza), Leon Lissek (Bailiff Sergeant), Susan Brodrick (Teri), Ian Trigger (Clown), Nike Arrighi (Gypsy Girl), Peter May (Janco), John Moore (Priest), Joan Haythorne (Cook), Marianne Stone (Kitchen Maid), Charles Farrell (The Seller), Sally Adcock (Bertha), Anne Stallybrass (Pregnant Woman), Paddy Ryan (Man), Michael Cadman (Young Man), Hulya Babus (Belly Dancer), Leslie Anderson, Biddy Hearne, Diana Sawday (Gypsy Dancers), Gary Rich, Andrew Burleigh (Boys), Ismed Hassan, Albert Wilkinson (Midgets).

At the funeral of Count Nadasdy, his elderly widow, Elizabeth Bathory (Ingrid Pitt), is attracted to handsome young Imre Toth (Sandor Eles), son of the Count’s best friend. Elizabeth later attends the reading of the will and is outraged to learn that she is to share her inheritance with her daughter Ilona (Lesley Anne Down).

That night, one of Elizabeth’s serving girls is cut by a blow from the cruel Countess, and blood spatters across Elizabeth’s face. As the girl flees, Elizabeth makes a startling discovery: In the places where blood touched her, her face glows with youthful freshness. Elizabeth orders her maid Julie (Patience Collier) to bring back the girl. Not long afterward, Captain Dobi (Nigel Green), Elizabeth’s steward and longtime lover, stares incredulously as Elizabeth, young again, confronts him. Elizabeth arranges to have her own daughter Ilona abducted and plans to assume her identity.

The now-youthful Countess pursues Imre, who believes her to be Ilona. Whenever her youthful appearance begins to fade, her maid finds another victim. When Elizabeth announces her engagement to Imre, Dobi is overcome by jealousy. He reminds the Countess that each time she loses her beauty, she grows more hideous.

Widow Elizabeth Bathory (Ingrid Pitt) and Captain Dobi (Nigel Green) attend the reading of Count Nadasdy’s will in Countess Dracula.

After a night of revelry, Dobi and Imre return to the castle with a serving wench. Elizabeth has confined herself to her room, once again aged. Dobi taunts the Countess and brings her to Imre’s room where she sees him in bed with the serving girl. Furious, Elizabeth murders the girl, but bathing in her blood has no effect. Dobi and the Countess go to the library to consult an occult volume. Fabio (Maurice Denham), the castle librarian, confronts them, holding the book they were seeking and reads a passage pertaining to the magical properties of virgin blood. The serving wench was not a virgin, and therefore her blood failed to produce the desired effect. The Countess offers to reward Fabio in exchange for his silence. Fabio appears willing but later is overheard by Dobi trying to warn Imre. Imre soon finds Fabio’s body, and accuses Dobi of the murder. Dobi takes Imre to the Countess’s rooms, where the young man witnesses the Countess bathing in the blood of another victim. Elizabeth assures him that she and “Ilona” are one and the same, and threatens to have him falsely accused of Fabio’s murder if he exposes the truth.

Investigating Fabio’s death, Police Captain Balogh (Peter Jeffrey) orders a search of the castle and uncovers the bodies of several missing girls. Balogh orders everyone but “Ilona” and the Countess placed under house arrest. Without access to victims, the Countess begs Dobi to find someone for her. On the day of Elizabeth’s wedding, the real Ilona is brought to the castle by Dobi to be the next victim. Julie, who raised Ilona since birth, brings Imre to her and pleads with Imre to save the girl. Imre tells Julie to bring the girl to the stables during the wedding; he will arrange safe passage for her. Ilona pleads with him to leave with her, but Imre knows that he has implicated himself and that he will never be able to escape.

During the wedding ceremony, Elizabeth loses her beauty as all in attendance witness the horrible transformation. Elizabeth, now insane, sees Ilona and tries to stab her, and Imre is killed in a struggle. Later, as the Countess awaits the hangman, the villagers whisper the new name they have given her: Countess Dracula.

Hammer’s version of the “Blood Countess” is far more tame than the real Elizabeth Bathory!

Hammer proclaimed its latest picture as “The first Horror film to be based completely on a true story.” Actually, Elizabeth Bathory—the “Blood Countess”—had lived a life of such depravity that not even Hammer dared to tell her story. Composer Harry Robinson told Little Shoppe of Horrors’ Bruce Hallenbeck that, originally, director Peter Sasdy was not interested in making a horror picture. “They were making a historical drama. The only thing was, I think they just got lost. Somebody from the front office said, ‘This is supposed to be a horror movie, so they put something in. It would have been more horrific if they’d actually stuck to what Elizabeth Bathory did.” Ingrid Pitt told Sam Irvin Jr. (Bizarre) that the film was “absolutely butchered by various people. It wasn’t really much of a horror film. I didn’t think it was cruel enough, horrifying enough. It needed more cruelty, throat slashing, blood hounds, blood! She ripped girls apart with her blood hounds; she froze them in the snow. She did incredible atrocities.” The Countess was accused of having killed over six hundred fifty people and is listed in The Guinness Book of World Records.

Production began on Countess Dracula on July 27, 1970. The screenplay was a combination of ideas from Sasdy, producer Alexander Paal, and Gabriel Ronay who later published The Truth About Dracula based on his research. The picture was Hammer’s first of three to be co-produced with Rank, although 20th Century–Fox handled the overseas distribution. Countess Dracula wrapped on September 4. While it was being edited, Peter Sasdy described to The Kinematograph Weekly how he perceived the “Hammer audience” by splitting it into three groups. “One: the large number of people who go to the films to be frightened; Two: those who go for a certain kind of laugh; and Three: the type of audience that goes for sexual thrills.”

Countess Dracula was trade shown on February 3, 1971, at the Rank Theatre and premiered on a double bill with Hell’s Belles on February 6 at the New Victoria. The package took £3,718 the first week, but business tailed off quickly. Michael Carreras later admitted that the company lost money, and the reviewers were more impressed than the audiences. The Kinematograph Weekly (February 6, 1971): “Ingrid Pitt manages to give her two ages notably different personalities”; The Monthly Film Bulletin (March): “At its best the film employs the kind of romantic imagery one associates with Keats”; The New York Daily News (October 7, 1972): “A pleasant surprise in the horror film genre”; and The New York Times (October 12): “Better than most in a sea of trashy competition.”

Although Countess Dracula does have its merits, it was another step down and miles away from “real” Hammer movies like The Brides of Dracula. Sadly, this was Nigel Green’s last film. He committed suicide on May 15, 1972.