Released July 30, 1972 (U.K.); 88 minutes; Technicolor; 7920 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Anglo-EMI Release (U.K.); filmed at Elstree Studios, England; Director: Harry Booth; Producers, Screenplay: Ronald Wolfe, Ronald Chesney; Based on the television series; Director of Photography: Mark McDonald; Art Director: Scott MacGregor; Editor: Archie Ludski; Music: Ron Grainer; Production Supervisor: Roy Skeggs; Production Manager: Christopher Neame; Camera Operator: Neil Binney; 1st Assistant Director: Ken Baker; Continuity: Doreen Dearnaley; Sound Mixer: John Purchese; Wardrobe Mistress: Dulcie Midwinter; Makeup: Eddie Knight; Hairdresser: Ivy Emmerton; Casting Director: James Liggat; Publicist: Jean Garioch; U.K. Certificate: A.

Reg Varney (Stan Butler), Doris Hare (Mrs. Butler), Anna Karen (Olive), Michael Robbins (Arthur), Bob Grant (Jack), Stephen Lewis (Inspector Blake), Pat Ashton (Norah), Janet Mahoney (Susy), Caroline Dowdeswell (Sandra), Kevin Brennan (Mr. Jenkins).

Stan Butler (Reg Varney), bus driver and local terror, announces his engagement to Susy (Janet Mahoney). His mother (Doris Hare), her son-in-law Arthur (Michael Robbins), and her daughter Olive (Anna Karen), who sponge off Stan, are horrified. They ask Stan to postpone the wedding, but—with fellow driver Jack (Bob Grant)—contrive to get Arthur a driving position. Stan teaches Arthur to drive a bus, disrupting the company’s timetable. Labor relations are made worse by the arrival of Mr. Jenkins (Kevin Brennan), a new depot manager. Somehow, Arthur gets the job, but due to a raise in his rent, Stan still cannot marry. He tries to get a transfer to a better route, and blackmails the flirting Jenkins into arranging it. Unfortunately, the route is to Windsor Safari Park, and Stan’s unlocked bus attracts several lions and monkeys on a trial run. Adding to Stan’s misery, Jack is transferred, and Inspector Blake (Stephen Lewis), who accompanied him on the safari run, has been demoted. He is now a conductor on Stan’s bus.

Hammer celebrated its 25th anniversary in November, 1972, but the company’s productions that year gave little artistically to celebrate. On the Buses had been a major hit the previous year, earning back seven times its cost. Hammer got the sequel going by offering £1000 for the best title in a contest run in The Sun. Production began on February 21, 1972, with many of the original’s cast and crew returning. On the same day, the company opened its new office, Little Hammer House, at Elstree. Filming ended on April 1, and Mutiny on the Buses was released on the ABC circuit on July 30 with The Cowboys. At the Edgeware Road Cinema, the pair brought in a healthy £1868. Cinema TV Today (August 5) called the film “very big,” but U.S. distributors showed no interest in a sequel to a film based on a British television series. Reviews were uncomplimentary, but failed to deter anyone, as Mutiny on the Buses earned sizable profits. Typical was Cinema TV Today’s (July 1): “More tightly written and plotted than its predecessor, but the jokes are too obvious, and performances too exaggerated.”

Mutiny on the Buses poster (courtesy of Fred Humphries and Colin Cowie).

Although films like this did earn a profit, they did little to enhance the company’s reputation.

Released 1973 (U.K.), June, 1974 (U.S.); 91 minutes; Movie Lab Color (U.S.); a Hammer Film Production; an Avco-Embassy Release (U.K.), a Paramount Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Elstree Studios, England; Director, Producer, Screenplay: Brian Clemens; Producer: Albert Fennell; Director of Photography: Ian Wilson; Production Supervisor: Roy Skeggs; Music: Laurie Johnson; Musical Supervisor: Philip Martell; Editor: James Needs; Production Design: Robert Jones; Production Manager: Richard Dalton; Assistant Director: David Tringham; Continuity: June Randall; Casting Director: James Liggat; Fight Arranger: William Hobbs; Camera: Godfrey Godar; Makeup: Jim Evans; Hairdresser: Barbara Ritchie; Assistant Art Director: Kenneth McCallum Tart; Wardrobe Supervisor: Dulcie Midwinter; Sound Recordist: Jim Willis; Dubbing Mixer: Bill Rowe; Sound Editor: Peter Lennard; Recording Director: A.W. Lumkin; Sound System: RCA; Film Processing: Humphries Labs; Publicity: Jean Garioch; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: R. U.S. Title: Captain Kronos—Vampire Hunter.

Horst Janson (Kronos), John Carson (Dr. Marcus), Shane Briant (Paul Durward), Caroline Munro (Carla), John Cater (Prof. Grost), Lois Daine (Sara Durward), Ian Hendry (Kerro), Wanda Ventham (Lady Durward), William Hobbs (Hagen), Brian Tully (George Sorell), Robert James (Pointer), Perry Soblosky (Barlow), Paul Greenwood (Giles), Lisa Collings (Vanda Sorell), John Hollis (Barman), Susanna East (Isabella Sorell), Stafford Gordon (Barton Sorell), Elizabeth Dear (Ann Sorell), Joanna Ross (Myra), Neil Seiler (Priest), Olga Anthony (Lilian), Gigi Gurpinar (Blind Girl), Peter Davidson (Big Man), Terence Sewards (Tom), Trevor Lawrence (Deke), Jacqui Cook (Barmaid), Penny Price (Prostitute).

The tiny village of Durward has seen several of its local girls mysteriously drained of youth. Dr. Marcus (John Carson) sends for his friend Captain Kronos (Horst Janson), who arrives with his hunchbacked partner, the brilliant Professor Grost (John Cater), and Carla (Caroline Munro), a young woman they befriended on their way to the village. Kronos, a professional vampire hunter, tells Marcus that vampires come in many different varieties yet all drain the life from their victims in one way or another.

Grost and Carla set to work burying toads in small caskets along the roads outside the village. According to folklore, if a vampire passes near a dead toad, the animal will return to life. The vampire hunters return later and, unearthing the boxes, find a living toad. Kronos finds a set of fresh carriage tracks nearby, and he and the others follow the trail. Marcus notices that they are near the estate of the Durward family. He excuses himself and pays Paul Durward (Shane Briant) a call, hoping to find clues.

Both Paul and his elderly mother (Wanda Ventham) hold Marcus responsible for the death of Paul’s father, Lord Hagen, during a plague years before. Later, Marcus is attacked by a mysterious hooded figure.

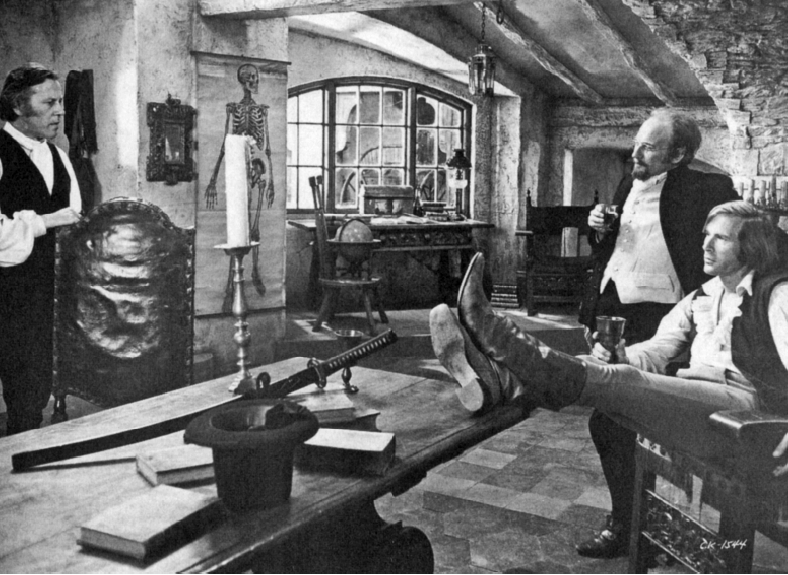

Dr. Marcus (John Carson, left) confers with the vampire hunters (Horst Janson, with boots, and John Cater) in Kronos.

Marcus, now young-looking, realizes that he has been made a victim of the vampire and begs Kronos to kill him. Kronos and Professor Grost try every known method, but none is successful. In a fit of rage, Marcus lunges toward the men and then dies, the doctor’s steel crucifix having been embedded in his chest during the struggle.

Kronos’ investigation leads him to suspect the Durwards. Carla infiltrates the mansion and is offered lodging by Paul and his sister Sara (Lois Daine). Later that night, Carla is visited by Lady Durward. Hearing Carla’s screams, Paul and Sara arrive and are astonished to see their mother no longer aged, but young and beautiful. Lady Durward explains that she was born a Karnstein—one of the infamous family of vampires. She also tells them that their father did not die of the plague, but was given a new existence as one of the undead. While Paul and Sara look on, Lord Hagen (William Hobbs) enters. It was he who preyed on the women of the village. Kronos intervenes in time to save Carla, engaging Lord Hagen in a swordfight and running him through with a steel blade. Lady Durward throws herself at Kronos and is also fatally impaled.

Having accomplished their mission, Kronos and Professor Grost depart, continuing their quest to rid the world of evil.

Kronos was a departure from Hammer’s standard vampire tale, much as The Kiss of the Vampire had been a decade earlier. The vampires are not of the usual blood drinking variety—they drain their victims of youth. Time honored methods of vampire extermination were discarded in favor of the magical properties of steel. Gone were detection by mirrors and crosses. They were replaced by the laying of dead toads in the suspected vampire’s path. If the suspect is undead, the toads are returned to life.

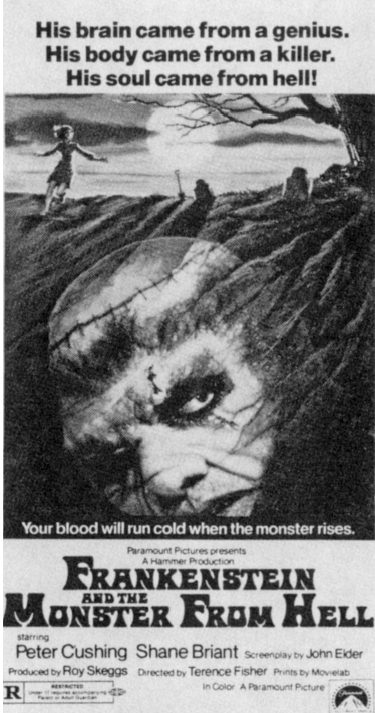

Poor promotion ended a potentially fine series of vampire hunter adventures; note amplified American release title for Kronos.

The film was Brian Clemens’ first as a director, and he had a definite plan. “The basic concept behind Kronos,” he told The Monster Times, “is a very deep one: to liberate horror pictures.” He asked to see other Hammer films to get a feel for the subject. “What I found,” he said, “was that by the time I got to the third Dracula, I couldn’t distinguish it from the first one.” Clemens had accurately pointed out Hammer’s problem—repetition—and sought to cure it. Concluding that Dracula had inadvertently been made a hero, Clemens said (Starburst 30), “You’re rooting for a villain, even though you know he’s going to end up staked through the heart. I thought it would be good to change the emphasis and have a proper hero.” Looking ahead, Clemens planned using Kronos (which is Greek for time) in a series of films in which he would move through the centuries. Unfortunately, although Horst Janson looked the part, he lacked the conviction (or the talent) to be totally believable. John Cater’s Professor Grost was an ideal sidekick, with his physical deformity a direct contrast to Kronos’ physical perfection. The supporting actors were well-cast, especially Shane Briant in another excellently played off-beat role.

Despite the film’s fresh approach, Michael Carreras was unimpressed. “The ‘Clemens team’ didn’t have the proper expertise with this type of material,” he said (Fangoria 63). “During the shooting, I discovered they weren’t making Kronos with the same reverence as the experienced Hammer team. It may be totally my own failing, but I wasn’t in tune with their approach.” Unfortunately, Carreras—who was seeking a new look for the company—failed to see that he’d found it.

After spending three weeks preparing the script, Clemens began filming on April 10, 1972, with a £160,000 budget and a seven week schedule, wrapping on May 27. The film was distributed in the U.K. by Avco Embassy, and Paramount released it in America in October in support of Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell.

Kronos suffered poor distribution in both Britain and America and received few reviews, but most were vaguely positive. Cinema TV Today (March 25, 1974): “An ingeniously different variation.” The New York Times (October 31): “Foolish, though elaborately produced”; and Variety (June 26): “Clemens keeps his plot going for 91 minutes with a sincerity which almost makes it work.” The film, even with its flaws, was one of the company’s most entertaining seventies productions. Janson might have grown into the part if a series had developed, but it was not to be.

Released 1973 (U.K.); 81 minutes; Eastman Color; 7315 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a Fox-Rank Release (U.K.); filmed at Pinewood Studios, England, and on location; Director: John Robins; Producer: Michael Carreras; Screenplay: Peter Lewis, based on the television series; Director of Photography: David Holmes; Editor: Archie Ludski; Art Director: Scott MacGregor; Production Supervisor: Roy Skeggs; Production Manager: Ron Jackson; Camera Operator: Chick Antiss; 1st Assistant Director: Bill Cartlidge; Continuity: Leonora Hail; Sound Mixer: Les Hammond; Wardrobe Supervisor: Rosemary Burrows; Makeup: Eddie Knight; Hairdresser: Jeannette Freeman; Casting Director: James Liggat; Publicist: Jean Garioch; Music: David Whitaker; U.K. Certificate: A.

Bill Fraser (Basil Bulstrode), Raymond Huntley (Emanuel Holroyd), David Battley (Percy), John Ronane (Mr. Smallbody), Dennis Price (Mr. Soul), Sue Lloyd (Miss Peach), Richard Wattis (Simmonds), Roy Kinnear (Mr. Purvis), Eric Barker (Pusher), Hugh Paddick (Window Dresser), John Sharp (Mayor), Michael Ripper (Arthur), Frank Thornton (Town Clerk), Geoffrey Sumner (Lord Lieutenant), Dudley Foster (Mr. Grimthorpe), Bob Todd (Funeral Director), Peter Copley (1st Funeral Director), Michael Robbins (2nd Funeral Director), Harry Brunning (Invalid), Geraldine Burnett (Petrol Pump Attendant), Stacy Davies (Grimthorpe’s Driver), Michael Knowles (Man with Car), Verne Morgan (Pensioner), Carol Catkin (Model in Window), Ken Parry (Porter), Clifford Mollison (Whiterspoon), Michael Sharvell-Martin (Policeman), John J. Carney (2nd Policeman).

After burying Mr. Grimthorpe (Dudley Foster), their longtime rival, the partners of the Holroyd Funeral Home—Emanuel (Raymond Huntley), Percy (David Battley), and Basil (Bill Fraser)—celebrate at the Undertakers’ Ball. Their joy, however, is short lived when a new competitor—The Haven of Rest—fills the vacuum. Eager for business, Emanuel jumps at the chance to bury Mr. Taylor, an important official. He runs into Mr. Smallwood, the Haven’s owner, at the train station when he goes to collect the body. Smallwood, actually a drug dealer, is waiting for a coffin filled with marijuana, and naturally, each takes the wrong coffin. Emanuel is now forced to “borrow” a wax effigy of Taylor for the viewing.

The two begin a grotesque battle over the coffin, and, totally confused, Percy and Basil take the wrong coffin to the crematorium. When they realize their error, they hand out the drugs to the mourners. Smallwood’s gang is arrested, and the ceremony is judged to be a great success. When Mr. Purvis (Roy Kinnear), the waxworks proprietor, comes to claim his effigy for bronzing, he ends up with Mr. Taylor’s corpse. The body is duly dipped and set in cement in the town square.

After spending many years terrifying audiences with corpses, Hammer decided to use one for laughs. Based on a popular television series, That’s Your Funeral was filmed between June 12 and July 7 at Pinewood by first-time Hammer director John Robins. Not surprisingly, this “lowbrow” effort was panned by the critics after its spotty release. Cinema TV Today (January 19, 1974): “A minuscule plot stretched too thin to conceal its weakness. The comic capers are repetitive and predictable, and the pace slows to a crawl at the end while all the loose bits of plot are gathered up into a bundle”; and The Monthly Film Bulletin (July): “Another nail in the British film industry’s coffin.”

The film’s premise was a bit thin, but Robins, a veteran of the Benny Hill series, was a perfect choice to get the most out of the script’s double entendres and bad puns. The veteran cast was a plus, as was an unexpected surprise for those “in the know.” Appearing under the opening credits as mourners were Robins, Roy Skeggs, and Michael Carreras, as well as members of the crew. The company’s love affair with spinoffs of low life television series is hard to fathom, and Hammer would have been wise to view the title of this one as a warning.

Released June, 1973 (U.K.); 86 minutes; Color; 7686 feet; a Hammer Granada Production; an Anglo EMI Presentation; an MGM/EMI Release (U.K.); filmed at Elstree Studios; Director: John Robins; Producer: Michael Carreras; Associate Producer: Roy Skeggs; Screenplay: Tom Brennard, Roy Bottomley, based on the television series by Vince Powell and Harry Driver; Director of Photography: David Helms; Production Manager: Ron Jackson; Art Director: Scott MacGregor; Editor: Chris Barnes; Assistant Director: Bill Cartlidge; Sound Recordist: Les Hammond; Sound Editor: Frank Goulding; Camera Operator: Chick Antiss; Continuity: Lorley Farley; Makeup: Eddie Knight; Wardrobe Supervisor: Rosemary Burrows; Hair-dresser: Jeanette Freeman; Assistant Art Director: Don Picton; Construction Manager: Arthur Banks; Dubbing Mixer: Gordon McCallum; Casting Director: James Liggatt; Music Composer: Derek Hilton; Music Supervisor: Philip Martell; Song “Nearest and Dearest” by Hylda Baker and Derek Hylton; Sung by Hylda Baker; U.K. Certificate: A.

Hylda Baker (Nellie Pledge), Jimmy Jewel (Eli Pledge), Eddie Malin (Walter), Madge Hindle (Lilly), Joe Gladwin (Stran), Norman Mitchell (Vernon), Pat Ashton (Freda), Bert Palmer (Bert), Peter Madden (Bailiff), Norman Chappell (Man on Bus), Yootha Joyce (Mrs. Rowbottom), John Barrett (Joshua Pledge), Adele Warren (Stripper), Carmel Cryan (Hostess), Sue Hammer (Scarlet O’Hara), Janie Collinge (Vinegar Vera), Donald Bisset (Vicar), Kerry Jewell (Claude), Nosher Powell (Bouncer).

Joshua Pledge (John Barrett), founder of Pledge’s Purer Pickles, is dying and wants to see Eli (Jimmy Jewel), his long lost son, one final time. His daughter, Nellie (Hylda Baker), traces Eli through a newspaper ad, and he returns home just in time to see his father die—and pop out his false teeth. Eli and Nellie now own the company, but Eli would rather have received money. He decides to modernize the plant despite Nellie’s objections.

When the plant closes for summer holiday, they go to a Blackpool boarding house run by the Widow Rowbottom (Yootha Joyce). She falls for Eli, who has eyes for only Freda (Pat Ashton). He plans to marry Nellie off to Vernon Smallpiece (Norman Mitchell) and have the business to himself. Vernon is shy, but urged on by Eli, makes his move. Complicating matters, Cousin Lilly (Madge Hindle) and her husband, Walter (Eddie Malin), soon arrive.

When the holiday ends, the plant reopens, and Vernon pops the question to the sadly ignorant Nellie, who is coached in “the facts of life” by Eli. When “The Day” arrives, the pickle people assemble as Eli walks Nellie down the aisle. Vernon is still undecided, but has his mind made up when he is arrested for his many unpaid bills.

Nearest and Dearest was yet another example of Michael Carreras’ attempt to remake Hammer. Although the company continued to make horror movies, it was relying more and more on comedies. A new type of advertising began to appear in the British trade papers, casting Hammer as a producer of “fun films” rather than trading off its Frankenstein/Dracula image. Like so many Hammer films before it, Nearest and Dearest had its beginning on television.

The film went into production on July 2, 1972, on a four week schedule, produced by Michael Carreras—only his fifth in this capacity in the seventies. The production was ignored by the trade papers, who were perhaps tired of the company’s television spinoffs. It is difficult to understand Hammer’s direction at this time. Although the comedies made money, they were unreleasable in America, and the once profitable horror movies were dying at the box office. Despite Carreras’ intentions, Hammer had not gone upscale. Instead of being associated with horror, the image of the company was now of a “low-life” producer of comedies.

Following an April 26, 1973, trade show at Metro House, Nearest and Dearest was released in June on the ABC circuit to indifferent reviews like Cinema TV Today’s (April 28, 1973): “Should prove popular whenever traditional variety shows are produced. Love it or loathe it.” A sequel, Nearer and Dearer, was planned, but like many seventies projects, it was cancelled along with a soccer comedy, Just for Kicks. A filmed-in-Australia thriller, A Gathering of Vultures, suffered the same fate.

Sadly, some projects that were cancelled seem more interesting than those actually filmed, as Hammer was laughing its way out of business.

Released May, 1974 (U.K.), October, 1974 (U.S.); 99 minutes (U.K.), 93 minutes (U.S.); Technicolor; 8921 feet; a Hammer Film Production; an Avco Embassy Release (U.K.), a Paramount Release (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Elstree Studios, England; Director: Terence Fisher; Producer: Roy Skeggs; Screenplay: John Elder; Music: James Bernard; Music Supervisor: Philip Martell; Violin Soloist: Hugh Bean; Director of Photography: Brian Probyn, BSC; Art Director: Scott MacGregor; Editor: James Needs; Sound Recordist: Les Hammond; Production Manager: Christopher Neame; Camera: Chick Antiss; Makeup: Eddie Knight; Continuity: Kay Rawlings: Wardrobe Supervisor: Dulcie Midwinter; Hairdresser: Maud Onslow; Assistant Director: Derek Whitehurst; Sound Editor: Roy Hyde; Dubbing Mixer: Maurice Askew; Construction Manager: Arthur Banks; Casting Director: James Liggat; Assistant Art Director: Don Picton; Processed by: Studio Film Labs. Ltd.; Sound Recording: RCA; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: R.

Peter Cushing (Baron Frankenstein), Shane Briant (Dr. Simon Helder), Madeline Smith (Sarah), David Prowse (The Monster), John Stratton (Asylum Director), Michael Ward (Transvest), Elsie Wagstaff (Wild One), Norman Mitchell (Sergeant), Clifford Mollison (Judge), Patrick Troughton (Body Snatcher), Philip Voss (Ernst), Chris Cunningham (Hans), Charles Lloyd Pack (Prof. Durendel), Lucy Griffiths (Old Hag), Bernard Lee (Tarmut), Sydney Bromley (Muller), Andrea Lawrence (Brassy Girl), Jerold Wells (Landlord), Sheila Dunion (Gerda), Mischa De La Motte (Twitch), Norman Atkyns (Smiler), Victor Woolf (Letch), Peter Madden (Coach Driver), Janet Hargreaves (Chatter), Winfred Sobine (Mouse), Tony Harris (Inmate).

Dr. Simon Helder (Shane Briant) is arrested for accepting delivery of a stolen corpse and sentenced to the Carlsbad Asylum. An admirer of Baron Frankenstein, Helder is looking forward to meeting his mentor there. However, when he tricks his way into the asylum director’s (John Stratton) office, the supervisor informs him that although the Baron was a former “resident,” he is now dead.

Two brutal warders drag Helder off and are hosing him down with a high-pressure water hose when the asylum director, Dr. Victor (Peter Cushing), appears. Helder recognizes him as the Baron. “Victor” orders that Helder be brought to his clinic where his mute assistant, Sarah (Madeline Smith), tends his wounds. Frankenstein offers Helder a position as his assistant.

Frankenstein later introduces Helder to his “special” patients Tarmut (Bernard Lee), a sculptor, and Durendel (Charles Lloyd Pack), a former mathematics professor. That night, Helder witnesses the burial of Tarmut and notices that the inmate’s hands are missing.

Helder finds Frankenstein’s secret lab where an incredible creature (David Prowse) is confined in a cage. More Neolithic than human, the creature is eyeless and has the hands of Tarmut. Frankenstein discovers Helder in his lab and explains that the creature was once an inmate who was committed for slashing people with broken glass. When the inmate attempted to commit suicide, Frankenstein kept him alive as a framework for a new creation, and has replaced his hands in hopes of eliminating his murderous traits.

After Durendel hangs himself, Frankenstein and Helder transplant his brain into the body of the creature. But Helder’s mounting suspicions concerning his mentor’s sanity are confirmed when the Baron confides his plan to mate Sarah with the monster. When the Baron leaves the asylum to purchase equipment, the creature escapes and kills the director. Surrounded by screaming inmates, the creature panics. Sarah, shocked back into speech, rushes to protect it but the inmates, fearing that the creature will harm her, attack the monster and tear it to pieces.

When the Baron returns, he quiets the patients and returns to his lab. While Helder stares in disbelief, Frankenstein says that he now knows where he went wrong and is ready to begin once again.

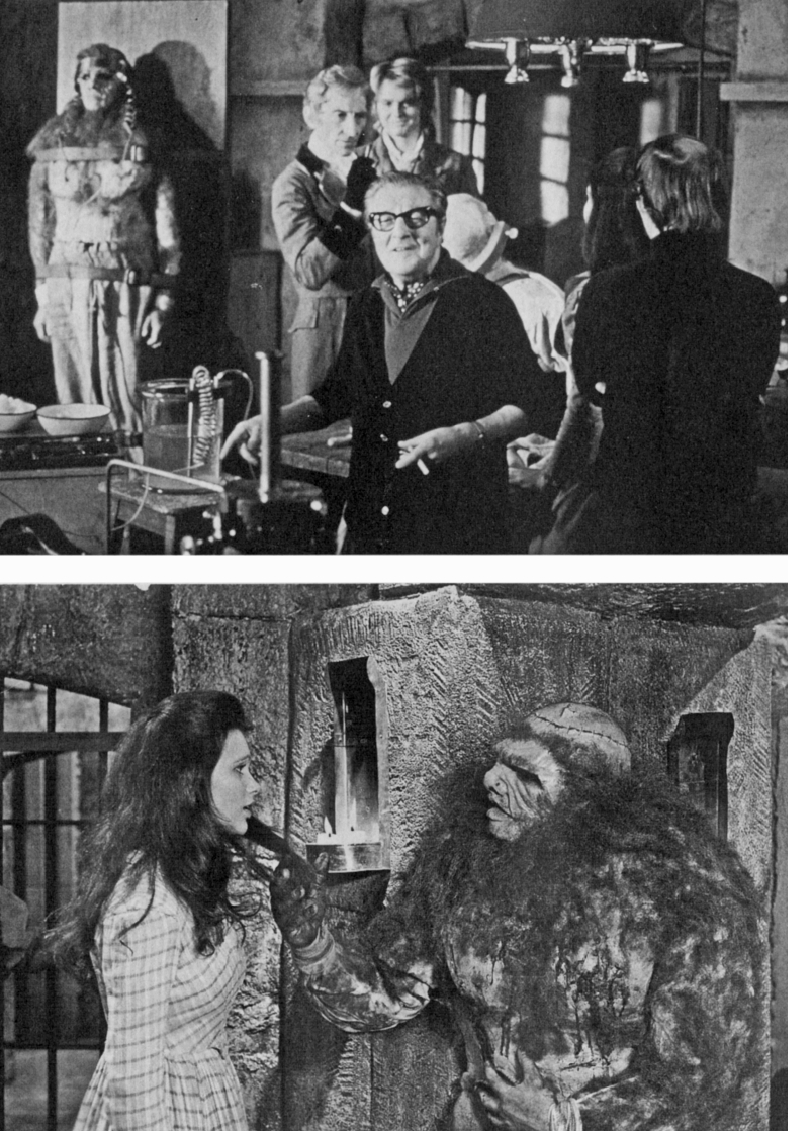

Top: Terence Fisher smiles as Peter Cushing and Shane Briant look on (photo courtesy of Ted Okuda). Bottom: The Baron has sinister plans for his assistant, Sarah (Madeline Smith) and his creature (Dave Prowse) in Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (photo courtesy of Ted Okuda).

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell ended a great deal of Hammer history. It was the last of Peter Cushing’s six appearances as the Baron and was the last Hammer film for both director Terence Fisher and writer Anthony (John Elder) Hinds. Although far from the best, it was an appropriate end to the sixteen-year-old series. The picture began production on September 18, 1972, and wrapped up on October 27. Back for a second—and much better—outing as the monster was 6'7" Dave Prowse, hidden under a Neolithic mask and hairy body suit designed by Eddie Knight and Les Bowie. Prowse painted a grim picture for the ABC Film Review. “I could only wear the costume for short periods. It was warm and thirsty work. The costume got terribly hot after a time working under all those studio lights, and, for part of the day, I couldn’t see where I was going as the mask covered my eyes.”

Fisher was opposed to this excessive makeup, and told interviewer Sam Irvin, “I disagreed with them from the start and tried my best to limit the makeup. However, they had sold Paramount on the idea that the monster would be this grotesque hairy beast, so I could not make him human, but I reduced him as far as I could without ruining what they had sold it on.” Prowse thought highly of his director and told the authors (February, 1993), “Terry was a wonderful person to work with—sort of the doyen of the horror film. He was really a wonderful guy and gave me a lot of help and direction—unlike many who give you nothing at all except to have you just get on with it. This film probably gave me more satisfaction than any other I’ve done—including Star Wars (1977). For example, Peter and I did a stunt; when we were finished, everyone on the set just stood up and applauded. It was the first time I’d ever seen anything like that! It was just great!” Fisher’s ability to install sympathy for his Frankenstein monsters is one of his enduring qualities as a director. “It is really a very sad story,” he said (Hammer press release). “He is a sad, pathetic creature.”

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell is the most symbolic in the series. The Baron has found refuge in the only place that truly fits him—a mental institution—for he is now truly insane. Gone is his goal to create “the perfect man,” as Prowse’s monster obviously illustrates. Each of the patients who “contribute” to its creation embodies a facet of Frankenstein’s own character: the delusion of being God, a brilliant intellect, the refusal to give up, and the ability to compensate for a physical infirmity. As in The Revenge of Frankenstein, the Baron again uses his patients for body parts, but this time there is no hint of concern for the afflicted.

Peter Cushing and Terence Fisher’s farewell to the Frankenstein series.

The picture was released on May 12, 1974, in the U.K., following premier engagements at the Astoria and the New Victoria, during which it took £1774 and £1308 in the first week. These modest figures reflected the public’s waning interest in the characters, and it was, apparently, time to put the series to rest. Critics were, however, split. The London Times (May 5, 1974): “Efficiently horrible”; The Daily Express (May 3): “Dr. Helder should learn a trade”; Cinema TV Today (May 11): “Peter Cushing’s Baron throws a cloak of elegance over the gruesome malarkey”; Variety (June 26): “An economy of filmmaking that is missed in more ambitious efforts”; and The New York Times (October 31): “Chock full of the old horror film values we don’t see much of anymore.”

Although the film has an open ending, there was really nowhere for the series to go. Unlike the Dracula series, Frankenstein went out with a bit of dignity. The series was never updated, and if one discounts Horror of Frankenstein (which really wasn’t a series entry), the Frankenstein pictures were all quality productions. The Hammer Frankenstein series went out as it came in, led by Peter Cushing’s typically fine performance and Terence Fisher’s sound direction.

Released January 13, 1974 (U.K.), November, 1978 (U.S.); 87 minutes; Color; 7830 feet; a Hammer Film Production; a Columbia–Warner Bros. Release (U.K.), Dynamite Entertainment (U.S.); filmed at MGM/EMI Elstree Studios; Director: Alan Gibson; Producer: Roy Skeggs; Associate Producer: Don Houghton; Screenplay: Don Houghton; Director of Photography: Brian Probyn; Camera Operator: Chick Antiss; Music: John Cacavas; Assistant Director: Derek Whitehurst; Continuity: Elizabeth Wilcox; Sound Mixer: Claude Hitchcock; Art Director: Lionel Couch; Wardrobe Supervisor: Rebecca Breed; Makeup: George Blackler; Hairdresser: Maud Onslow; Casting: James Liggat; Stills Cameraman: Ronnie Pilgrim; Editor: Chris Barnes; Production Secretary: Sally Pardo; Dubbing Mixer: Dennis Whitlock; Production Manager: Ron Jackson; Music Supervisor: Philip Martell; Special Effects: Les Bowie; U.S. Title: Count Dracula and His Vampire Bride; U.K. Certificate: X; MPAA Rating: R.

Christopher Lee (Count Dracula), Peter Cushing (Van Helsing), William Franklyn (Torrence), Michael Coles (Inspector Murray), Joanna Lumley (Jessica), Freddie Jones (Prof. Keeley), Barbara Yu Ling (Chin Yang), Valerie Ost (Jane), Richard Vernon (Col. Mathews), Maurice O’Connell (Hanson), Patrick Barr (Lord Carradine), Lockwood West (Gen. Freeborne), Peter Adair (Doctor), Richard Mathews (Porter), Maggie Fitzgerald, Mia Martin, Finnula O’Shannon, Pauline Peart (Vampires), Marc Zuber (Mod C), Graham Reese (Guard), Ian Dewar (Guard), and John Harvey, Paul Weston.

London, 1972. A secret branch of British Intelligence has five important officials under surveillance at Pelham House. The agent assigned to the case has gone mad, raving of Black Magic. Inspector Murray (Michael Coles) calls on Professor Van Helsing (Peter Cushing) for help. Murray and Jessica (Joanna Lumley), Van Helsing’s granddaughter, unwisely go to Pelham House and are taken prisoner. Van Helsing later recognizes an old friend—Professor Keeley (Freddie Jones)—in a surveillance photo. When he encounters Keeley, the man is raving, and confesses that he has been forced to develop a new strain of plague—with no antidote.

Van Helsing learns that the project is being funded by D.D. Denham, a reclusive billionaire never seen in daylight. After Keeley is murdered before his eyes, Van Helsing discovers that Denham is actually Count Dracula (Christopher Lee). Bored with his immortality, Dracula plans to destroy all life on earth, ending his blood supply. But first, to avenge himself against the Van Helsings, he plans to take Jessica as his “bride.” Taken to Pelham House by Dracula, Van Helsing finds that the officials are all under the Count’s power. When Porter (Richard Mathews) accidently drops a phial of the bacillus, Murray escapes in the confusion and sets the house ablaze, destroying the virus. After Murray frees Jessica, they are pursued into the forest by Dracula who dies when he becomes entangled in a hawthorn bush.

Compared to Hammer’s original Dracula, Lee’s final appearance as the Count was a disgrace, and one can easily sympathize with his decision not to play the part again. Dracula had simply been done to death. The updating idea had failed, and that was that. No series character can go on forever, and Dracula had a long run; but the race was over before The Satanic Rites of Dracula got to the starting line. “Every Dracula film beginning with Has Risen,” said Don Glut (Monsters of the Movies 2), “has not really been the Count’s story. Hammer’s writers design a tale about some secondary characters, then search their brains for some way in which to insert Dracula.” Lee told Glut, “I’m doing this one under protest. I don’t think people appreciate it either, because people who go to see a character like this go to see him seriously.” Hammer also seemed to be rudderless, announcing fifteen upcoming productions, none of which was made.

Trapped in a hawthorn bush, Count Dracula (Christopher Lee) awaits his inevitable demise in The Satanic Rites of Dracula.

The Satanic Rites of Dracula began filming on November 13, 1972, with location work in and around London. The working title—Dracula Is Dead and Well and Living in London was kept, incredibly, throughout the editing stage—as late as February 17, 1973. By this time, Lee had become disenchanted with horror movies in general. He told Cinema TV Today, “I have no desire to make any more horror films that are not good ones.” He clearly indicated the one just completed. Lee was not alone in his lack of enthusiasm for the film. After its completion on January 3, 1973, The Satanic Rites of Dracula could not find a distributor. A few years earlier, a Hammer Dracula with Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee would have had distributors standing in line. But, as Ron Borst pointed out (Photon 21), “These days of blind faith and confidence seem to be quickly disappearing.” A few things had happened since the picture was planned. Dracula A.D. 1972 had been a disappointment, and The Exorcist (1973) took the horror movie into another dimension. Suddenly, a new Dracula movie did not look like much.

The film finally opened at the London Rialto on January 13, 1974, earning a decent £4211 the first week. But as word of mouth spread the bad news, the tickets stopped selling, reaching a low point of £847 at the Columbia Warner. The scheduled spring opening in America was dropped, as was one planned for Halloween. The film eventually surfaced as Count Dracula and His Vampire Bride in 1978, released through Dynamite. Critics were not amused. Cinema TV Today (January 26, 1974): “A hodgepodge of incidents and bare-breasted girl vampires”; The Sunday Times (January 20): “It offers no great novelty”; The Los Angeles Times (November 24, 1978): “Routine Hammer horror fare”; and Variety (November 24): “Silly and dull.”

This was a sad way to end both Christopher Lee’s Dracula performances and his Hammer association with Peter Cushing, who found this one beyond even his powers to save.