CHAPTER XVI

ITALY, SPAIN AND THE FUTURE

The call was from Signora Gnolli, the photographer of an Italian magazine, asking me if I would like to work in Florence for the collections. I agreed like a shot and arrangements were made for me to fly to Florence to meet her. We were to spend ten days photographing the Italian couture collections. I was thrilled with the idea and wrote immediately to Emilio Pucci, who had a couture house in Florence and Rome. (He had come to London to show his collection a few months before, and I had been on the committee organizing it; I had also taken part in the show at the Savoy Hotel, after which he asked me to do his show for him if I ever came to Italy.) He wrote that I would have to go over a few days earlier to do some fittings. When I arrived in Florence, Emilio met me, looking like an Italian Byron in his open-necked white silk shirt. He took me out to lunch in his Alfa Romeo, after which I had to do a lot of fittings.

When Signora Gnolli arrived I had to work harder than I’ve ever done before; we had to get up at five o’clock in the morning to be out photographing by six o’clock so as to catch the early morning sunlight as by eleven the sun was already too strong to take good pictures; we went on photographing again in the late afternoons until the light failed, and sometimes all day indoors which was stifling as it was the hottest summer ever. My sightseeing of Florence was done the hard way, posing for Signora Gnolli on the Ponte Vecchio, the famous shop-lined bridge or by the statue of David, or in the various Palazzi and hills around Florence. Wherever we went the Signora shouted and screamed at me in a mixture of Italian, French and English like an old fish-wife, in front of the inevitable crowds that gathered every time we stopped to take a picture, which rather spoilt my first impressions of Florence. We also worked a lot in the Strozzi Palace where photographers from all over the world were photographing clothes. Some of them had not brought their own mannequins so they would come up to me and say: ‘Please can you spare just five minutes to pose in this red cocktail dress (or this black suit), I’ll pay you double.’ Every time I had to say: ‘I can’t, I’m under contract.’ Signora Gnolli had put me under contract for ten days which meant that I couldn’t do photographs for anyone else, although I could do shows if she happened not to be using me. If I had not been under contract to any photographer or magazine I could have worked all day long at the Strozzi Palace for different photographers and made a small fortune.

In the afternoons if I was not posing for photographs I did shows at the Pitti Palace. I loved the way the Italian model girls showed: they have a wonderfully lazy animal walk. I have seen English models try and walk like that but they don’t succeed—it just makes them look rather cheap, because it is not instinctive with them.

The show that Pucci arranged was to be a midnight gala at the Tennis Club, which is the chic place in Florence. The women all wore evening dress and the men were in dinner jackets. It was an almost tropical night with a beautiful full moon, a Neapolitan orchestra playing and candle-lit tables set outside—altogether very romantic.

The clothes we had to show were really beautiful and I wanted to have them all: heavenly slacks, cut like nobody else can cut them in the world, bathing costumes that really ‘did’ something for one’s figure, and beautiful silk shirts and shorts, all in the most gorgeous colours and materials. Unfortunately, we had to model round the edge of the swimming pool, and as it had been floodlit, the light blinded us and it felt like walking on a tightrope. I was terrified of falling in the deep end!

On the last day of working in Florence I asked Signora Gnolli to pay me the money she owed me. ‘Come to the station with me,’ she said, ‘I’ll give it to you there.’ At the station she handed me some money and stepped on to the already moving train. I soon learnt why she was so anxious to pay me at the very last minute—she had given me exactly half the amount agreed upon, which after paying my hotel bill for ten days and various other expenses, left me with practically nothing. I could have willingly murdered her; as it was, I couldn’t even touch her. She was safely on her way to Paris. I had worked for at least ten hours a day for ten days, and put up with heaven knows what rudeness, only to be swindled at the end. The maddening thing was that she had cleverly not written a letter to me confirming the booking, but had done it all by telephone, so I had absolutely no proof of the contract. Even writing about it now makes my blood boil. Everyone I told about it afterwards said Signora Gnolli was well-known for her crooked dealings, and that no one who knows her would work for her without first having the terms in black and white. The worst part about it all was that I had hoped to take a holiday in Italy on the money I made; now I wouldn’t be able to afford the hotel bill. This particular matter was solved fortunately by a friend called Maureen Williamson, who at that time was the fashion editress of The Queen, and who had taken a villa in Taormina, where she was having her friends to stay as paying guests. I went there and for a few weeks had the most wonderful holiday, falling in love with all the beautiful Sicilians and forgetting all about my recent unpleasant experience.

The following spring I worked in Rome for various Italian houses, showing at the Excelsior Hotel. One morning I went wandering round the town and up a small side street I discovered a little shop where they made to measure the most wonderful shoes at about £5 a pair; I ordered a pair, feeling very pleased with my discovery. Some time later I happened to be wearing them at a party in London, Edward Rayne, the Queen’s shoemaker, was also there. He admired my shoes and said: ‘Those could only be made by “Dalco”.’ ‘That’s right,’ I replied, ‘but how on earth did you guess because it’s a little shop I’ve discovered in Rome.’ ‘He only happens to be the best shoemaker in the world,’ was the unexpected answer, which from one shoemaker about another was extremely generous praise. All the same I was disappointed to realize I had not discovered ‘a little man around the corner’.

Some time had passed since I had asked Mrs Juda to release me from going to show in St Moritz for her, and now three years later I was booked to do another show there, this time by Deanfields, the London and Paris furriers. As it was February, it was the height of the season in St Moritz, with millionaires springing up like mushrooms all over the place, and caviare and champagne as common as cauliflower and cheese sauce. Mr Deanfield had booked two models from Paris, two from Zurich and two of us from London (a new model called Ginia Blakeley and me.) We stayed at Suvretta House and had a wonderfully gay time, with only two gala shows, a rehearsal and a few photographs to do during our whole week’s stay—the rest of the time we spent sunbathing and watching the bob sleighs on the Cresta run, or dining and dancing at the Palace Hotel. Jean Cocteau was staying at our hotel, he broke his golden rule of going to bed before 11 p.m. by staying up to watch our midnight gala show. I met him later and he said he would never waste time watching a dress show normally, but as it was a fur show, that was very different, as furs were so beautiful. Among the furs I showed was the mink jacket that Price Rainier gave to Grace Kelly as a wedding present. The jewels we wore were flown from Paris with two men guarding them. One necklace of fantastic dark rubies was alone worth more than all the furs put together. The whole week in St Moritz was the sort of dream job that people always imagine models have, but which they rarely do—mostly play and very little work, except for slinking around in a few sables— absolute heaven!

Soon after the St Moritz show I was off to Barcelona in Spain to work for Rodriguez, the leading Spanish house there. I had always longed to work in Spain and each time I had been going something had happened to stop me. This time nothing stopped me, and I was soon adjusting myself to the Spanish way of life—to dinner at ten o’clock or later, to siestas in the afternoon, to flamenco dancing and bullfights—although at first I couldn’t get used to the show starting at five o’clock each day.

The fashion world in Spain is practically non-existent. There are very few fashion magazines and the few they have are of a very low standard, mostly with badly produced pictures from foreign magazines. The only good fashion photographer is Ramon Batlles and he is first class with a studio as up-to-date as tomorrow. He takes the most terrific colour pictures, and I worked for him soon after I arrived.

The Spanish mannequins are the worst paid in the world and are rather looked down upon in Spain. They get paid about 800 pesetas a month which is about £2 a week, in addition to being given two outfits from each collection. So a model from another country must obviously have a special contract with the couturier and take some of her own foreign allowance, which is what I did as I thought it was worth the experience, and I wanted to see Spain.

There are no model agencies, as there are no freelance models. The only models there are, work in the couture houses of which there are about thirty, twenty in Madrid, seven in Barcelona and a few in San Sebastian. Most Spanish women buy material for their clothes and either make them themselves or have a dressmaker. Only the very rich and visiting foreigners patronize the couture houses. Rodriguez told me he had a terrible time getting customers to pay. I was not surprised when I heard his prices, which were extremely high for Spain, from £80 for a suit or dress.

After I had been in Barcelona some weeks, I decided I must go somewhere quiet and get on with writing this book. I heard that Formentor in Majorca was very peaceful and cut-off; it sounded the ideal place. Off I went and stayed at the one and only hotel. About ten days after I arrived, there was great excitement in the little bay, as the yacht Deo Juvante arrived, completely unexpectedly, bearing Prince Rainier of Monaco and his Princess, on their honeymoon.

The night after they anchored in the Bay of Formentor, they accepted an invitation to be guests of honour at a dinner in the hotel; when the Monégasque anthem was played, the Prince and Princess were the only people who recognized it and stood to attention, whilst everyone else busily surged around photographing them and standing on chairs to watch. The next day Henriques Garriga, the Vice-President of the Clube Nautico, invited the newlyweds to drive round by horse-drawn carriage with a view to showing some land which would be presented to them by Formentor. He asked me to come too, saying jokingly that I could represent the Queen of England. So I had a first-hand account instead of the twisted newspaper versions of the famous wedding in Monte Carlo, which MGM had filmed and the BBC had televised. Princess Grace was living up to her new title of the Serene Highness. She really was serene, even when people ‘bobbed’ to her and called her ‘Ma’am’, she took it all in a stride, as if it had been happening all her life. It was wonderful to be included in the invitation for lunch on their yacht the following day and I had an amusing time, comparing views with the Princess on wearing spectacles. We both agreed we couldn’t hear so well without them! There had been a lot of complaints about the large white hat she had worn on arrival in Monte Carlo from New York. She explained: ‘You know how it is when one’s buying hats. At first a new line looks awful, then gradually your eye gets accustomed to it and eventually with all the salesgirls telling you it looks divine you get talked into buying something you hated at first sight.’ So that was how I came to be lunching with them at the beginning of this book.

From sixteen to sixty most women are intrigued by models and modelling. As a career it has increased enormously in popularity since the war, and the labour exchanges and employment agencies are getting worried by the countless girls who want to become models when they leave school.

In an age when time is all important, everyone seems to be looking for short cuts in life and getting something for nothing with the least effort involved. Superficially modelling seems to fulfil these requirements, needing nothing beyond a pretty face, good figure, and very little training. But make no mistake about it, being glamorous every day is hard work and modelling, far from being a world of fantasy, is one of harsh facts.

Would I be a model all over again? I think of all the drawbacks, the insecurity, the stiff competition, the long irregular hours spent often in extreme temperatures, the disappointments when one is cancelled or not booked for jobs, and the fact that modelling in itself is not a satisfying career after a time, it leaves one feeling frustrated. Then I think of the credit side, the variety and chances to travel compared with the boredom of sitting in an office all day, the good money and freedom from authority and routine, the poise and dress sense one acquires—it’s fun wearing the latest fashions before anyone else—and the number of other jobs it leads to. But after all it is not a question I can answer impartially because I have been one of the lucky ones and obviously I’m influenced by my personal experiences.

I think that there is an awful lot of luck involved in being a successful model—luck in being available for a particular job, luck in having the right measurements for a certain assignment. But I also realize there comes a point when luck ends and one’s own efforts and personality take over. No one can give another person ambition and perseverance if it isn’t in their character, and modelling certainly needs that.

What am I going to do now that I am retiring from modelling?

The other day a friend of mine said: ‘Now that you’ve written a book, Jean, when are you going to plant your oak and start your nursery?’ I was rather mystified until she explained that it was a saying of Confucius that ‘Everyone should write a book, plant a tree and have a child, so that when they die they leave something of the mind, something of the body and something of the earth, to live after them,’ and although I’m sure Confucius wasn’t thinking in terms of models writing books nevertheless I think I’ll follow his advice and settle down.

Jean Dawnay wearing an evening dress with ermine stole and clutching a bottle of champagne, photograph by John French, November 1956

Jean Dawnay with photographer John French and assistant, 1950s

Jean Dawnay applying make-up before a shoot, photograph by John French, 1958

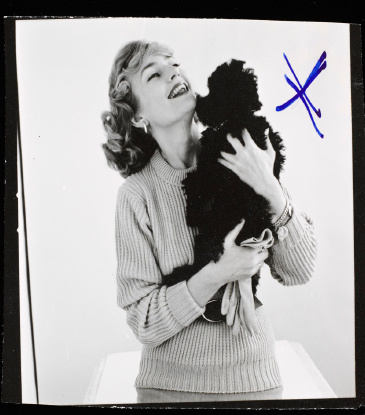

Jean Dawnay and dog – marked selection from a contact sheet, photograph by John French, 1956

Jean Dawnay photographed by Baron, the frontispiece to the original Weidenfeld & Nicolson edition of Model Girl, 1956