How to deal with frustration when memorizing

No matter how regularly you practice, and no matter how systematically you go about memorizing, there will always be occasions when the process of committing a piece to memory causes frustration.

For instance, you may have learned a certain piece very well, and are able to spontaneously play it by memory – except for that one passage where you more often than not “mess up”, and that throws you off track.

How can you successfully deal with such passages?

First of all, you should keep track of any parts that constantly slip your mind. Isolate them, and analyze them well, in order to discover just why it is that you can’t seem to memorize them easily.

Obviously, compositions such as Bach fugues may be full of such passages. Even advanced pianists commonly have trouble learning fugues by memory. After all, a fugue will typically contain three or four independent voices, each of which must be carefully studied, phrased, correctly articulated, etc. How much easier it is to learn a piece by Mozart or Haydn by heart!

Yet at times even classical sonatas that are well within your technical grasp might contain a passage that for some reason or another, you simply have trouble memorizing well.

Recently, I began to learn a sonata in b minor by Joseph Haydn. Using my method of memorizing from the computer screen, and dedicating no more than twenty or thirty minutes a day to the piece, I had the first movement memorized in about five days, without any trouble – except for a single passage, one that was technically easier than most. Whenever I played that movement through by heart, I would, at least half the time, make a mistake in that passage, and was often at a loss to remember the right notes.

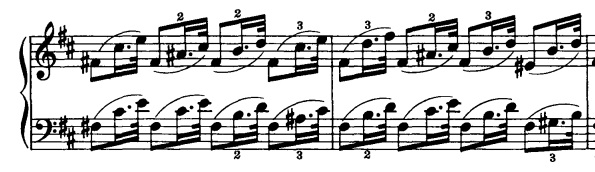

Here is the culprit:

The rhythms are all the same; technically, there is nothing difficult about this passage for me. The problem was remembering the sequence of harmonies:

Note that in the bass, the first chord is repeated on the second beat; in the upper part, on beat one, the notes are the same as those in the bass, though an octave higher; on beat two, however, the chord changes to an F-sharp major triad (F-sharp, A-sharp, C-sharp), whereas the bass repeats itself. Beat three has the two parts playing the same notes, but an octave apart, whereas beat four is the reverse of beat two: the bass part is the F-sharp major triad, whereas the treble has the same seventh chord that was played by the bass on beats one and two.

In measure two, the first beat has a 6-4 chord (second inversion of b minor) in the left hand, while the right also starts with F-sharp, but leaps to the sixth and the octave instead of the fourth and the sixth; beats two and three are an exact repetition of the same beats in the first measure.

Precisely because there is so much similarity in the upper and lower parts, it is easy to get confused, and play different notes with one hand. If the harmony played by one hand is compatible with that of the other hand, mistaken notes might even sound all right, which makes it all the trickier, since at times, you may think you are playing the passage correctly, only to find, upon re-examination of the score, that you have unintentionally changed some notes.

When you find a passage that holds up your progress, or that throws you off track, dedicate extra time to mastering it.

Learn each part (right hand and left hand parts, or, in the case of a fugue, each separate voice) separately by memory. And here, I of course don’t just mean “finger memory”: concentrate on memorizing the way each part sounds, for if you commit the passage to your aural memory perfectly, you will later immediately be able to hear any mistakes you make, and will have an easy time correcting them.

Naturally, problems memorizing certain passages aren’t always due to their deceptive simplicity, such as the one quoted above. On occasion, a certain section of a work may be hard to learn well due to the exceptional technical difficulties it presents.

Anyone who has played a number of Bach fugues will probably be aware that there is practically always an especially difficult measure or two in any given fugue, that is, a section that is at least two or three times as hard to play as any other measure in the piece. I don’t know whether Bach intended this, or whether it is just a coincidental phenomenon, created by the occasional technical demands that are the result of consequential contrapuntal voice leading, but having practiced the entire Well Tempered Clavier, I could easily point out such measures in each of the fugues.

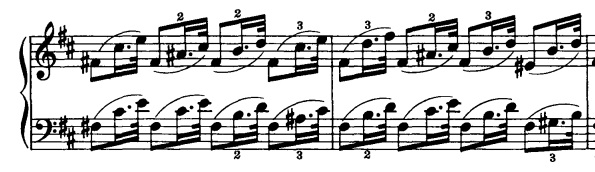

Here is just one example, taken from the first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, Fugue in g-sharp minor:

The two central measures here are anything but easy to play smoothly, even after one learns the notes. I had to isolate this section, and concentrate on conquering its difficulties before I was able to play it well. As so often with Bach, fingering is here the key, yet because this section is somewhat “clumsy” to play, it was necessary for me to repeat it many times before it went well, even with a very well-thought-out fingering.

The importance of constant repetition of certain passages in order to learn them well cannot be overemphasized. Some learners don’t like the idea of repeating the same passage ten, twenty, thirty times or more before moving on to the next, but it often is necessary.

What’s that you say? Repeating a section thirty times is simply too much? Well, let me tell you a little true story.

Years ago, I was reading a biography of the great Russian-American pianist, Vladimir Horowitz (“Remembering Horowitz”, by David Dubal; the following incident is on page 145). Horowitz was a legend, even in his life-time, being known for both his incredible technique as well as his highly individualistic style of playing that was reminiscent of the “great Romantic tradition” of piano playing.

One day, the accomplished pianist Leonid Hambro was walking by Horowitz’s house. He heard Horowitz playing a difficult passage in octaves; the master played it flawlessly. But then, Hambro, still listening outside, noticed that Horowitz repeated the passage; it went well the second time, too. After that, Horowitz continued repeating it, and the listener became curious as to how many times he would do so. He counted ninety-nine repetitions. In other words, the great Horowitz, who was already able to play the passage well, nonetheless repeated it nearly one hundred times!

Some time later, Hambro happened to meet Horowitz at a social occasion. He mentioned the incident, and asked Horowitz why in the world he practiced a section ninety-nine times, if he was able to play it well the first time?

Horowitz responded by saying that even though he knew the passage, there was always the possibility that during a recital, when one might be nervous, distracted, or whatever, one could easily mess up such a section; for that reason, Horowitz liked to practice such passages excessively, knowing that then, in the recital, his hands would quite automatically play them well, even if he did lose his concentration.

When I read that chapter, I asked myself the inevitable question: if the legendary Horowitz practiced difficult passages one hundred times, how many times should I practice those parts that give me trouble? A thousand? Ten thousand? A million??!!

Of course, life is too short for such ridiculous excesses. My only point here is that if even the greatest pianists find it appropriate to repeat technically demanding sections many times, then perhaps we normal mortals should take the hint, and follow their example!

Here, though, a danger can arise:

Can’t the excessive repeating of a single passage lead to becoming bored, losing focus, and ending up playing mechanically, due to the deadening of conscious concentration?

Yes, it can. But there are ways to repeat a section many times while maintaining interest, focus and concentration.