LONDON had in 1888, and still has today, two police forces: the City of London Police and the Metropolitan Police. Metropolitan Police headquarters, at the time of the force’s formation in 1829, was at 4 Whitehall Place.1 Its business entrance backed on to Scotland Yard, a legacy, in name only, of part of the Palace of Whitehall which had been destroyed in 1692. Scotland Yard soon became the public name for the police office and, with time, the public name for the force itself.

In 1888 the Metropolitan Police boundary extended over a radius of 15 miles from Charing Cross, excluding the City of London – an area of 688.31 square miles. It was policed by an establishment of 12,025 constables, 1,369 sergeants, 837 inspectors and 30 superintendents.

In 1839 a police force of 500 men under the command of a commissioner was appointed for the one square mile of the City of London. The Metropolitan Police had no jurisdiction within this area. Incredibly, it was not until 1844, 15 years after its formation, that the Metropolitan Police force was given jurisdiction over Trafalgar Square. This right had been refused until then because the area was Crown Property. An equivalent anomaly existed within the City with regard to the Temple in Fleet Street, which was home to two Inns of Court, the Inner and Middle Temple. Jurisdiction there was not granted until the Police Act 1964, and it was the personal experience of many City policemen to be ordered out of the Temple for trespassing even beyond that date by barristers wishing to demonstrate their authority.

There had been tremendous resistance to the formation of a metropolitan police force in 1829. It was widely believed that it would be modelled on the French system of spies and agents provocateurs. Among the many insults hurled at the men was that they were ‘Jenny Darbies’ (a corruption of the French gens d’armes, suggesting that they were spying not only on the streets but on the people). Other nicknames included ‘Raw Lobsters’, ‘Blue Devils’, ‘crushers’ (because of the way they hustled people), ‘Peel’s Bloody Gang’ and the more familiar ‘Bobby’.2 It would be several years before the public attitude towards them changed: they were not a well-liked body of men. Patrolling constables were sometimes beaten up, spiked on railings, blinded and on occasion held down on the road while a coach was driven over them. In 1831 an unarmed police constable was stabbed to death in a riot. Not only did the Coroner’s Inquest bring in a verdict of ‘justifiable homicide’, but an annual banquet was held every year to commemorate and celebrate the event. Unsurprisingly, four years later in 1833 only 562 men were left out of the 3,389 who had joined in 1829. Charles Dickens, a much quoted admirer of the police, was not so well disposed towards them in the early years after the force’s formation. His attitude, as reflected in his novel Martin Chuzzlewit, was probably a true reflection of public opinion in 1841. Old Martin Chuzzlewit’s nephew, Chevy Slime, after years of debts and debauchery, has purposely become a policeman to shame the family. His class has given him the rank of inspector. By joining he hopes that his uncle may feel some of the disgrace visited on the family by his being employed in such a way. For a working man joining the police force at this date seems to have been on a par with joining the army. Both were disgraceful professions. Public hostility is more understandable when it is appreciated that the recruits for both came from the same source of otherwise largely unemployable manpower.

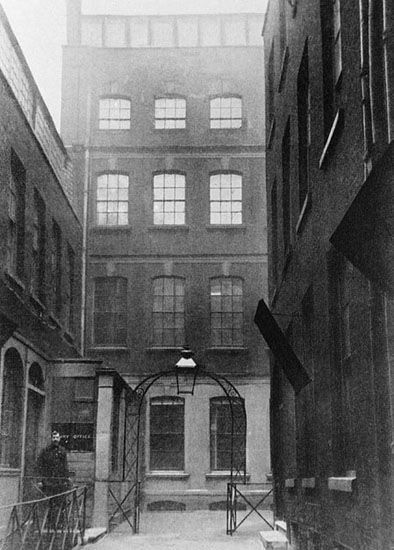

The entrance to Old Scotland Yard.

26 Old Jewry, headquarters of the City of London Police at the time of the murders. This ancient entranceway can still be seen, virtually unchanged, although the City Police headquarters have moved.

‘Men, dwarfs in height, and old in years, of divers bodily deformity, mentally weak, and with little or no character, had no hesitation to apply’, wrote the City Police Commissioner in 1861. His advertisement in 1861 attracted 570 applications for 43 vacancies; only 38 places could be filled, one of the main reasons for rejection being the poor physical condition of the majority of applicants. This was a problem that faced both London forces. In the first eight years of the Metropolitan Police 8,000 men were dismissed or forced to resign; the force’s average annual strength on paper, was 3,000. Contrary to popular myth, replacements were not chiefly from the army. In 1832 the two Metropolitan commissioners gave a breakdown of the former professions of those employed in order to rebut accusations that the police were nothing more than a disguised military force. These statistics make it clear that the police force was overwhelmingly working class. There were butchers, bakers, shoemakers, tailors, servants, blacksmiths, sailors, weavers, stonemasons and men from other trades. Over a third of the force comprised former labourers and the number of ex-soldiers was in the proportion of one to eight. The statistics also suggest that a high number had been unemployed when recruited. There were 20 Englishmen to every 10 Irishmen and 2 Scotsmen.

‘Curious looking policemen we were,’ said Thomas Arnold, who joined in 1855 and was superintendent of the Whitechapel Division in 1888, when reminiscing about the early days. The constable’s basic uniform was a blue swallow-tail coat with a high stand-up collar bearing his divisional letter and number, a tall chimney-pot hat, sometimes with a glazed leather top to aid identification when it was knocked off, a rattle and a 17-inch truncheon in the swallow-tail pocket. This was the same uniform issued to a 20-year-old clocksmith, Frederick George Abberline, when he joined the Metropolitan Police force in 1863. Only a year later his swallow-tail coat was changed to a frock tunic and the top hat swapped for a combed Britannia helmet. His wooden rattle was only to be sprung in emergencies. In 1884 the rattle was replaced by a whistle. The whistle and truncheon remained the beat policeman’s only aids until the 1960s.

To avoid the accusation of spy and agent provocateur, the London policemen had to wear their uniform both on and off duty. An armband showed whether a constable or sergeant was on or off duty. Constables and sergeants wore the duty armbands on their tunic wrists, for constables on the left wrist and for sergeants on the right. Metropolitan Police sergeants came to wear the band on the left wrist with the introduction of numerals on their collars which ran from 1 to 16. The Metropolitan Police’s armbands bore blue and white stripes, the City’s red and white. When washed the white stripes of the latter would, before the use of nylon, turn a delicate shade of pink, which the liberal use of chalk before a parade could never quite conceal. ‘Idling and gossiping’ was frowned upon and to avoid being caught City policemen would signal the sergeant’s approach by rubbing the right wrist in an exaggerated manner or the inspector’s approach by rubbing the tunic buttons up and down. In 1870 the uniform regulations were relaxed and for the first time in forty years policemen were allowed to wear their own clothes when at home or off duty.

Initially the recruiting age was between 19 and 45. A candidate had to be able ‘to read and write generally’, as contemporary advertisements put it. Physical strength was needed for the long hours of work and frequent changes of shift, which made recruitment from the working or labouring classes inevitable. Promotion could only be achieved rung by rung, upwards through the hierarchy. Officers were recruited from the sergeant-major class.

On appointment each man was issued with a training manual setting out his duties. The first policemen had no training school to teach them the basics and were literally pushed out on the street to learn the job for themselves. Some had to be stopped from carrying umbrellas! They were, however, under strict discipline, as there were fears for several decades that there would be no break with the past and that bribery and corruption would continue as they had done under the old watch and constable system. Discipline was imposed by drill and because this was carried out in public places it inevitably fuelled accusations that the police were a military organisation providing a bodyguard for the government. When he became Commissioner, Warren was frequently and unfairly criticised for militarising the police by excessive drilling. Part of the drill consisted of training in the use of cutlasses, a rack of which was normally kept in the inspector’s office for use in emergencies. That a policeman should use such a weapon is too bizarre to contemplate – the 1819 Peterloo massacre where the yeomanry cut down large numbers of peaceful demonstrators should have been warning enough. The one recorded instance of cutlasses being issued was in the Tottenham Outrage of 1909. Had the policemen involved tried to use them it would have been a somewhat unequal contest as the two gunmen were using Mausers.

Drilling, in fact, was necessary to ensure large numbers of men could get to an emergency in a hurry. It was equally important as a means of establishing that at the beginning of each shift men could be marched from the station and dropped off at their point or beat, and the beat man they had relieved could be marched back. Beats in the 1880s were worked at a regulation speed of 2½ miles per hour. The average length of a beat was 7½ miles for day duty and for night duty 2 miles. In densely populated areas this could be shorter still. In the City on the night of the Eddowes murder, it took PC Watkins just 15 minutes to patrol his beat. In the suburbs a beat normally took 4 hours. By day a policeman kept to the kerb side of the pavement; at night he took the inside to make him slightly less visible and to allow him to check doors and locks more easily. Inevitably complaints were made that officers could never be found when wanted and so, after 1870, fixed points were introduced where the public could find them and from which they were ordered not to move. The monetary fines that could be imposed meant such orders were rigidly obeyed and led to the ludicrous example of the Spitalfields constable who, when told of the Annie Chapman murder, refused to leave his post until relieved. By 1889 there were 500 fixed points where constables could be found between the hours of 9 a.m. and 1 a.m.

Victorian Metropolitan police officers filing out on patrol from Bow Street police station. Shifts left the stations and walked to their allocated beats in file, like this, both night and day.

Police officers were timed over their beats so that it was possible for the patrolling inspector or sergeant to go to a particular point knowing that the constable would be there too. This rigidity of practice meant, as noted by a City police officer writing anonymously to the Daily Telegraph in 1865, that a man could miss the chance of an arrest to guarantee that he kept the point with the patrolling inspector. A non-arrest would lead to the assumption that the constable was malingering or not correctly patrolling his beat, resulting in a fine which the ill-paid constable could not afford. Beat books were issued to City Police probationers until the 1960s. Each book contained a street map of every beat with the boundaries highlighted, together with a list of vulnerable properties on each beat. A constable was expected to check every building on the beats that he had been assigned and try the door-handles to make sure that the building was secure. A door found open on the next shift necessitated an explanation in writing by the first patrolling constable to the divisional superintendent. A later variation (no date has been found for its implementation) was for a constable to patrol his beats so many minutes one way and then walk a similar amount of time in the opposite direction. No break period was allowed during a shift and the unofficial practice, sanctioned by decades of use, was for the patrolling constable to take his refreshment at the back door of a convenient pub. At night, the practice was to take a tin flask of tea, shin up a lamppost on the beat and place it by the gas flare to keep warm so that a hot drink was available throughout the night. On high-value beats, night-duty constables were given bags of whalebone clips to insert in doors as wedges which would spring out if opened, giving warning of a possible illegal entry. Cotton marks were another way of seeing if illegal entry had been gained. The practice was still continuing in 1963 when Rumbelow was a probationer on ‘C’ Bishopsgate Division. As night-duty cyclist he had to check cotton marks throughout the division. That the practice was not taken seriously by the constables themselves was obvious: when Rumbelow went to his first building to cotton mark the protecting grille, which could not have opened in years, he found it so laced with threads that it would have been possible to use them as a ladder and climb in through the window. A City constable of an earlier generation recalled how when he went into Mitre Square, site of the Eddowes murder, to check his cotton mark, he found that one of his night-duty colleagues had pegged paper dolls along the thread.

By 1889 the policemen were being given one day’s leave every fortnight. There was no annual leave. One month’s day duty was followed by two months’ night duty. The day shift of 16 hours was split into four reliefs of 4 hours on and 4 hours off, beginning at 6 a.m. and finishing at 10 p.m. This engaged 40 per cent of the force. Night duty was 10 p.m. until 6 a.m. and 60 per cent of the force was available for this shift.

A policeman’s powers were limited to the area within his force’s jurisdiction, in other words, the police boundary. Outside that boundary, and within another force’s area, the only powers a policeman had were the ordinary rights of a citizen. As such, if he were sued, it would be as an ordinary citizen and not as a police officer. This did not change until the Police Act 1964 when jurisdiction was extended to the whole of England and Wales.

The most senior posts came under the patronage of the home secretary. According to historian David Ascoli, writing in 1979, ‘The six top posts in the Metropolitan Police are Crown appointments made on the advice of the Home Secretary, who is under no statutory obligation to consult the Commissioner. It is a potentially dangerous form of patronage, for there is absolutely nothing – other than the certainty of public retribution – to stop a Secretary of State from appointing three bus-conductors and three Methodist ministers of whatever impeccable virtue.’3 The dangers of such patronage were clearly evident when Howard Vincent was appointed Director of Criminal Investigations in 1878. His only superior at Scotland Yard was the chief commissioner but unofficially the home secretary told him that in his separate and independent department he could come and see him any time he liked. He should report direct to the Home Office and ‘not pay too much attention to what was said of him either by the chief commissioner, or anyone else at Scotland Yard’. This was a dangerous precedent; James Monro followed it in defying Commissioner Sir Charles Warren in 1888, an act that proved to be a major factor in the quarrel between the two men.

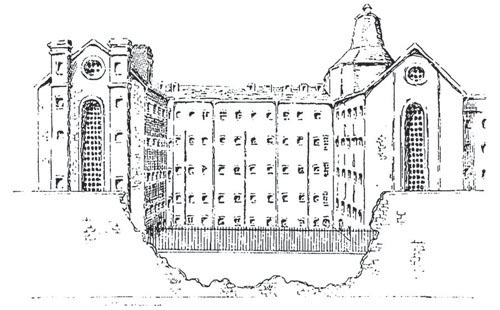

In 1867, while Warren was excavating in Jerusalem, outbreaks of Fenian disturbances disrupted the British mainland. The Fenians, the name derives from the old Irish fianna and means soldiers, were Irish nationalists; their chief aim was to force British withdrawal from Ireland. They had been organised in 1858 as the Irish Republican Brotherhood and in 1867 in America as the Clan na Gael. During the mainland disturbances, a police sergeant was killed when he was caught up in a Fenian rescue of two members from a prison van in Manchester in 1867. One of those heavily involved in the manhunt that followed was plain-clothes sergeant Fred Abberline, then based at Caledonian Road in north London. According to his own reminiscences, he discovered in the capital one of the men who made the attack upon the prison van; this man, a coachmaker, was sentenced to death but had his sentence commuted to penal servitude for life. Three other Fenians were hanged for the murder of the police sergeant. To the Irish community they became the ‘Manchester martyrs’, victims of British injustice. In November 1867 two more Fenians were arrested, one of whom had planned and organised the prison van rescue. Both men were committed to the Clerkenwell House of Detention, where a plot was made to rescue them. A hole was to be blown in the prison yard wall when the men were taken out for exercise. News of the planned escape was leaked to the authorities but security remained lax. On the day, a barrel containing 200 pounds of gunpowder was placed against the prison wall and several attempts were made to light the fuse, which proved to be damp and would not ignite. The first attempt was aborted by the approach of a passing policeman who watched without interest as the conspirators wheeled the barrel away. They returned the next day with a bigger barrel and nearly three times (548 pounds) as much gunpowder, which not only demolished a 60-foot section of the prison wall but also severely damaged the working-class houses on the opposite side of the street. Chief Inspector Adolphus ‘Dolly’ Williamson said that with their front walls gone they looked like so many ‘dolls’ houses with the kettles still singing on the hobs’. In the event, the rescue operation failed because the prisoners had been moved deeper into the gaol. Some 12 people were killed or died indirectly as a result of the explosion and a further 120 were injured, some seriously. In May 1868 Michael Barrett, one of six Fenians tried for this crime, became the last person to be hanged in public in England. It is possible that Abberline, involved in the case and based close by, witnessed this execution. The official explanation for the police failure to foil the plot was that although they had been told that a prison break was imminent, they were looking for signs of tunnelling because their information was that the wall was to be blown up; they were unprepared for it to be blown down!

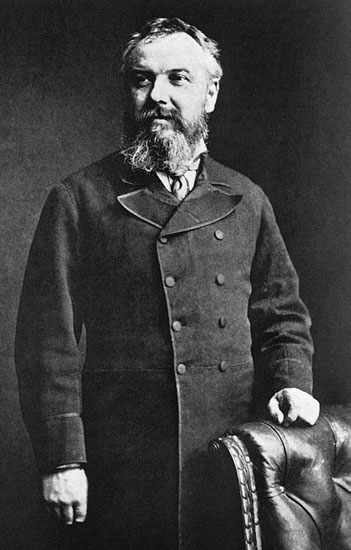

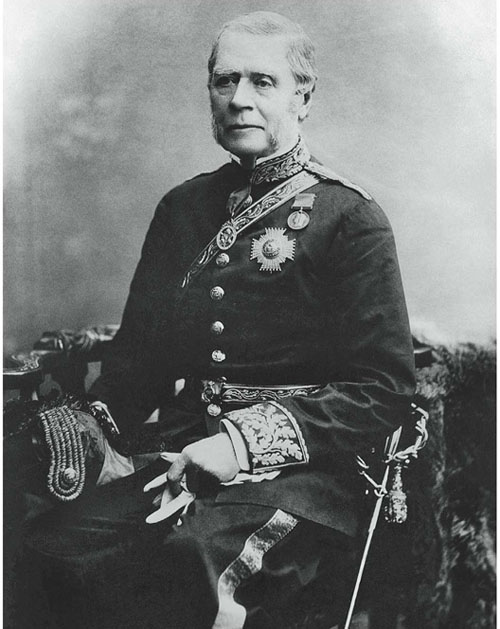

Chief Constable Adolphus (‘Dolly’) Williamson, aged 58 and ailing at the time of the murders, was probably the wisest and most experienced senior police officer in the Metropolitan Police force of the day. Anderson relied on him for advice. He died on 9 December 1889 and was replaced by Macnaghten. Williamson was the first career police officer to achieve this high rank and did so through merit.

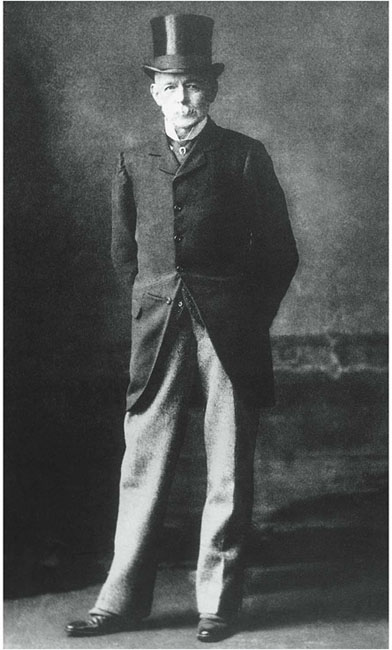

A warning of the planned break-out had been forwarded to the police by a young Irish barrister named Dr Robert Anderson who has been said by some to have drifted into secret service work. Anderson’s father was the Crown solicitor for Dublin and his brother had charge of all state prosecutions. These family connections led to his being asked to sift and sort a mass of foreign dispatches and reports, most supposed to be extremely secret, which were stored, unindexed and unregistered, in the chief secretary’s office. That was when, Anderson said, he took the queen’s shilling. The 24-year-old was entrusted with making a précis of the documents. His services were requisitioned again by the attorney-general when there was a Fenian uprising in 1867. Some 200 to 300 prisoners were marched into Dublin Castle and committed for trial on the charge of high treason. The problem the authorities now faced, nicely expressed, was that having caught so many hares, how would they cook them? Anderson was asked to look into each case and advise the Crown on which cases to prosecute. This gave him a rare insight into the workings and conspiracies of the Fenian brotherhood. His investigations allowed him to give London an early warning of the bombing campaign that was about to start but his warning was ignored.

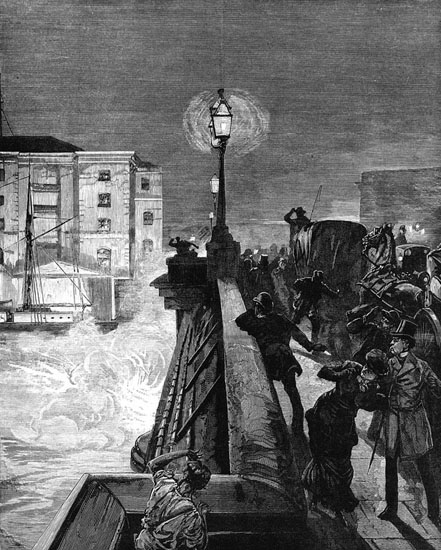

Sketch of Clerkenwell House of Detention after the explosion of Friday 13 December 1867, showing the 60-foot section of wall demolished in the failed bid to liberate two Fenian prisoners. Twelve people died and one of the Fenians tried for this crime, Michael Barrett, was the last man to be hanged in public in the United Kingdom.

In the panic that followed the Clerkenwell explosion, a police Secret Service organisation was formed and Anderson was summoned to England to take charge of it. The planned unit proved to be just a temporary expedient, lasting a mere three months, and Anderson was on the point of returning to Ireland to resume practice at the Bar when he was asked to take charge of Irish affairs at the Home Office. He was not only to advise on matters relating to political crime but was also given certain powers of investigation. Although his main work was to be centred on Fenianism and political crime, Anderson was given other tasks too. He became secretary to royal and departmental commissions, including the Prison Commission in 1877 and afterwards the Loss of Life at Sea Commission. In his spare time he dabbled in journalism, writing on ‘Criminals and Crime’ and ‘Morality by Act of Parliament’ as well as a number of religious books including The Bible and Modern Criticism, The Coming Prince: the Last Great Monarch of Christendom and A Doubter’s Doubts, which attracted the attention of Gladstone himself.

The death of Richard ‘King’ Mayne on Boxing Day 1868 brought to an end a 39-year reign. He was joint commissioner with Colonel Sir Charles Rowan when the Metropolitan Police force was created in 1829 and had ruled alone since Rowan’s death in 1852. Rowan was a soldier and Mayne a lawyer. The decision that had to be made now was whether the new commissioner should be a soldier or a civilian: in the event, a professional soldier with civilian experience was chosen. Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Edmund Henderson was a professional soldier by training, a Royal Engineers officer like Warren, but he also had a practical knowledge of the criminal classes acquired over thirteen years as comptroller of a convict settlement in Western Australia, followed by six years as director and surveyor-general of prisons at the Home Office. Described as a man of great personal charm he was able during his seventeen years as commissioner to work well with a succession of home secretaries. His early decision to allow policemen to wear beards and moustaches, so long as they did not cover the divisional numbers on their tunic collars, provoked a certain amount of public mirth. More importantly, under his regime men were allowed to wear plain clothes when off duty, although the blue-and-white duty armband continued to be an anachronistic piece of equipment until the 1970s.

This nice contemporary artist’s study of Dr Robert Anderson, the Assistant Commissioner, shows him at the time of the Whitechapel murders with his arm resting on his desk in his study at home.

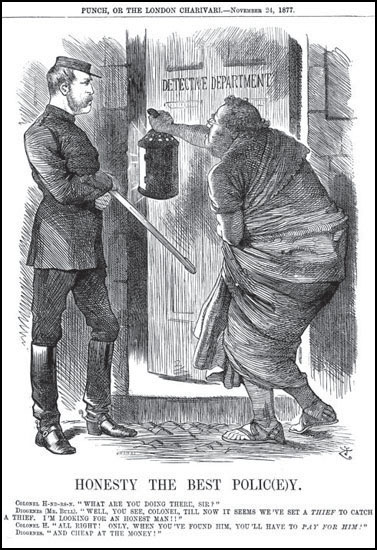

The year 1877 was a bad one for the Metropolitan Police. The scandal of corruption in the Detective Department resulted in the infamous ‘Trial of the Detectives’. Punch ran this satirical cartoon, ‘Honesty the Best Polic(e)y’, in October, showing Commissioner Henderson speaking with John Bull about honesty and the extra price that should be paid for it.

Inadequate pay for the lower ranks, however, was a major grievance and in 1872 a small number of policemen went on strike, holding meetings and public demonstrations to air their complaints. Initially Henderson said that he did not have the funds to pay for increases but when money was found it simply fuelled the men’s grievances about pensions and the lack of any sort of trade union to negotiate on their behalf, something the government refused to allow. Other improvements were made in living and working conditions. The size of the Detective Department was increased from 15 to nearly 200 men, eventually rising to nearly 260, which allowed detectives to be put into every division. There was still a great deal of public suspicion about plain clothes policemen, and, as Henderson recognised, a plain clothes detective was something ‘entirely foreign to the habits and feelings of the Nation’. In charge was Chief Inspector Adolphus Frederick Williamson, who had joined in 1852, and was eventually promoted to superintendent. Williamson was a second-generation policeman. When he joined in 1850 his father was the superintendent of the T or Hammersmith Division. He had a dry sense of humour, he was ambitious, and he spent his evenings learning French. His detective’s plain clothes were anything but plain: he normally wore a broad floppy hat and sported a large rosette in his buttonhole.

In 1877 public suspicions about detectives seemed to be justified when a scandal of epic proportions hit the headlines. It was corruption at the heart of the Detective Department. In the ‘Trial of the Detectives’ held at the Old Bailey three high-ranking men were shown to have been deeply involved with a gang of swindlers in turf betting frauds. The detectives had initially been able to protect their accomplices when investigations got too close, but eventually they over-reached themselves, were brought to trial and were given heavy prison sentences. One of the arresting officers was Detective Sergeant John Littlechild. He had been sworn to secrecy by Williamson himself who had begun to suspect his officers, one of whom was his immediate deputy. The sergeant found himself in the unpleasant situation of having to arrest three of his superior officers. ‘Dolly’ Williamson’s integrity was never in doubt. From their knowledge of the man it had been clear to the conspirators that he was someone who could not be bought but for a long time afterwards he, like others, was tainted by suspicion of corruption. Before the trial ended, a Home Office commission into the working of the Detective Department had already begun. Clearly there had to be a thorough overhaul of the department and it was necessary to bring someone in from the outside to head it. Even before the commission’s report was published it was widely assumed that the head of the reorganised department would have to be not just an assistant commissioner but someone who was also ‘an astute and experienced lawyer’. The successful applicant was a young barrister, Howard Vincent, who, seeing an impending opportunity, had gone to Paris and studied the French detective system. He then submitted a report, which he is said to have redrafted eighteen times, to the departmental committee investigating the scandal. Its members were persuaded by his arguments and accepted some of his recommendations. Vincent, however, was appointed not as a policeman but as a lawyer, ranking not as an assistant commissioner but as director, which made him responsible not to the commissioner but to the home secretary. Worse, he had no statutory or disciplinary powers over his department, although he could reform and reorganise it. Over the next six years he increased the size of the department to about 800 men.

Vincent’s assistant was Williamson, now promoted to chief superintendent. Vincent increased the detectives’ pay, improved the standard of training, compiled a police code and law manual which, with regular updates, became the policeman’s bible for another eighty years. More controversially, he brought in outsiders with special qualifications or skills, used agents provocateurs and courted press publicity. One reason for bringing in outsiders was that Vincent found the old divisional detectives, instituted by Henderson, to be mostly illiterate men, ‘many of whom had been put into plain clothes to screen personal defects which marred their smart appearance in uniform’. They were inefficient and did very little, living ‘a life unprofitable to themselves, discreditable to the service, useless to the public’. To emphasise the break with the past the old title of Detective Department was abandoned. The new name was the Criminal Investigation Department, or CID.

Between 1881 and 1885 there was a resurgence of ‘Fenian Fire’. A bombing campaign was carried out on mainland Britain with London the chief target. On 6 May 1882 the new Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and the Permanent Under-Secretary, Thomas Burke, were stabbed to death in Phoenix Park, Dublin, by four men. The weapons used were surgical knives. Similar knives were to be linked with the Jack the Ripper murders. In response to this ‘Fenian Fire’ (the term was used in Home Office circulars after the Clerkenwell explosion and is a reference to the incendiary Greek fire of classical times), Howard Vincent formed the Special Irish Branch (the ‘Irish’ was dropped in 1888) to combat this terrorism and the social unrest that was leading to large-scale demonstrations. Robert Anderson was one of those who advised on its creation. Anderson, who had remained in London after the Clerkenwell explosion to liaise between Dublin Castle and the Home Office, was still retained by the Irish government to look after its interests in London and to maintain contact with a network of informants on Irish and Irish-American conspiracies on both sides of the Atlantic. His role was now to liaise with ‘Dolly’ Williamson on a daily basis and brief him on intelligence matters.

Dynamiting London Bridge.

Initially the Special Irish Branch was a squad of four detectives and eight uniformed officers. Nominally in charge was Williamson but as he had command of the entire CID, day-to-day running was placed in the hands of John Littlechild, who had gone undercover for five months in Dublin after the Phoenix Park murders but was now promoted to inspector. In religion, Littlechild was a staunch Protestant and almost certainly anti-Catholic. His will would stipulate that no person professing or following any other than the Protestant religion would be entitled to reap any benefit under his will.

Special Branch headquarters was in a small two-storeyed building in the centre of Great Scotland Yard. An anonymous letter sent to Scotland Yard late in 1883 threatened ‘to blow Superintendent Williamson off his stool and dynamite all the public buildings in London on 30 May 1884’. Shortly after 9 p.m. on that date a bomb placed in the public urinal let into the ground floor of the building for the use of customers of the Rising Sun pub opposite blew away a corner of the Special Branch premises to a height of 30 feet, completely destroying Williamson’s office and extensively damaging the Rising Sun. Littlechild’s office was in the same building. He normally worked late but that evening a friend had given him two tickets for the opera and, as a musical man, he could not resist the temptation to use them. When he next saw his office it was in ruins, a large brick sitting on his desk chair. Other bombs were exploded that same night in central London. One unexploded device was found the next day at the foot of Nelson’s column.

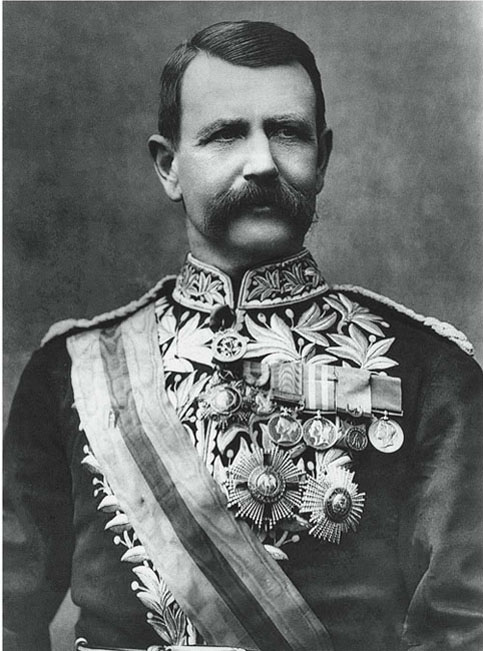

An unexpected consequence of this resurgent bombing campaign was the resignation of Howard Vincent as head of the CID. He had been anxious to retire for the past year but the home secretary had insisted on retaining him, much against his wishes. The bombing of the Special Irish Branch offices allowed him to break free, to enter politics as the Tory Member of Parliament for Central Sheffield. A successor was quickly found in the person of 50-year-old James Monro, who was home on leave from Bengal when the bomb destroyed the Special Branch offices. He was inspector-general of police in India. The home secretary was anxious to know whether his police experience in India had given him any practical experience in dealing with political crime. Monro was easily able to reassure him on that point. In 1864–5 he had been deeply involved in the detection and punishment of the Wahabi conspirators at Patna and was used to dealing with secret societies.

Moonshine, 25 February 1888, cartoons of Chief Inspector Littlechild of the Special Branch.

The Police Act 1856 had authorised the appointment of two assistant commissioners and in 1884 James Monro was appointed third Assistant Commissioner (Crime) to take over Howard Vincent’s role as Director of Criminal Intelligence, a rank that was now abolished and replaced by Assistant Commissioner (Crime). This new rank brought the appointee into the police hierarchy; he was a subordinate officer answerable direct to the commissioner. With his new position came the office of magistrate. Monro was sworn in as an executive justice of the peace which meant that he could swear in and command constables, and issue warrants and summonses. He could not, however, try criminal cases. Monro’s appointment regularised this situation but raised a more important issue: although as Assistant Commissioner (Crime) and Director of the Special Irish Branch (Section B) he was responsible to the commissioner, as head of Special Branch (Section D), which was imperially funded and not paid for out of Metropolitan Police funds, he was answerable only to the home secretary. This meant that the commissioner had no control over a subordinate officer, who, when acting as head of Special Branch (Section D), could draw on police manpower without giving any explanation as to how or why it was being used. This would have been an intolerable position under any circumstances.

Just after 9 p.m. on 30 May 1884 Old Scotland Yard was rocked by a Fenian dynamite explosion which severely damaged the north-east corner of the central building (which housed the Special Branch offices) and the Rising Sun pub opposite. There were five minor casualties, including the duty policeman, but Littlechild and Williamson were not in their offices.

The entrance to Old Scotland Yard, another view.

James Monro, Assistant Commissioner (Crime), 1884–8.

Monro was a Scotsman, born in Edinburgh in 1839, and educated at Edinburgh and Berlin universities. As a 19-year-old, he joined the Indian Civil Service (Legal Branch) in what his obituary notice describes as ‘one of the early batches of “competition-wallahs”’ in 1858. He was sent to Lower Bengal and after various district and secretarial posts was appointed inspector-general of police in 1877, a position he held until 1883, the year prior to his posting to the Metropolitan Police. According to The Times obituary of 30 January 1920, he had a tenacious memory for facts and faces, names and details of cases, which made him the terror of the criminal classes of Bengal and subsequently of London. The story was later told of an old Punjab Brahman who had been making a nuisance of himself and was brought to Scotland Yard and shown into a large office. Confronting him was a sun-tanned, military-looking man with grey hair and a moustache, who said sharply, ‘What do you mean, you shameless one, by coming into a sahib’s room with your shoes on?’ Hearing Hindustani, the man hurriedly shuffled off his shoes as he began his explanations to Monro whom he saluted throughout their brief conversation as ‘Protector of the Poor’ and ‘Incarnation of Justice’. He was cautioned by the Assistant Commissioner as to his future behaviour and led out.

On his appointment Monro learned that there was a kind of central bureau of intelligence collecting information on the Fenian dynamiters and acting as a clearing house for this material which was gathered chiefly from America and then circulated to police forces. Head of this department was Edward Jenkinson who was unofficially dubbed ‘spymaster-general’. He was Harrow educated and, like Monro, had been an Indian civil servant. After the Phoenix Park murders of 6 May 1882 he had been appointed assistant under-secretary for police and crime at Dublin Castle. Threats from abroad to blow up the London bridges and to explode a little dynamite near to the queen led to Jenkinson’s secondment from Dublin Castle to the Home Office in London in 1884. This gave him direct access to the home secretary and Anderson, and to Williamson at Scotland Yard. Jenkinson, originally in Dublin, and Anderson in London had begun their almost three-year working association in the autumn of 1882 and their relationship continued, it is said, on the basis of ‘mutual distrust and jealousy’. Both men protected the names of their informants from each other – Anderson went so far as to refuse to tell the home secretary when asked for informants’ names.

Jenkinson’s move to London, to the Home Office, on 7 March 1884 meant that Anderson was now working for both him and Vincent. At his insistence Great Britain and Ireland were to be treated as one. Not only was Jenkinson to be the one pair of hands through which all information gathered at home and abroad would pass. He could issue emergency orders without consulting the minister (something that Anderson had never claimed nor tried to do), only informing him afterwards of what action he had taken, and he could spend secret service money at his own discretion. The centre of his web at the Home Office was room 56. He had a low opinion of Anderson’s abilities and lack of informants, about which he regularly made criticism to the home secretary. Within three months of Jenkinson’s move to London, Anderson was stopped from liaising with Williamson and retained only on the understanding that he would increase his number of informants. The evidence suggests that he had only one. When this did not happen, the home secretary gave him a brutal dressing down, which should have precipitated his resignation but Anderson said he could not do without the money. A way out of this impasse was found by compensating him with a gift of £2,000 and relieving him of all his duties relating to Fenianism in London. He was then consigned to the bureaucratic wilderness as secretary to the Prison Commissioners.

Monro was initially prepared to work with Jenkinson until he discovered that Jenkinson was going far beyond his brief to collect intelligence. Although he was not a policeman and had no police authority, he had his own private force of Irish policemen stationed in London, acting under his directions and without any reference to the London forces. Jenkinson’s abuse of his position, even before Monro took up his post, was already causing friction between the two and Monro’s irritation soon became evident when he realised that while he was expected to give Jenkinson all the information that came into his possession, the arrangement was not reciprocal.

This enlarged detail of the Leman Street police station group photograph shows the bowler-hatted, mutton-chopped detective with a stick that Donald Rumbelow feels fits the sketches and descriptions of Inspector Abberline, of whom no photograph has been found thus far.

A Victorian group photograph of police officers of H Division at the rear of Leman Street police station. This photograph would appear to pre-date January 1887, when truncheon cases were abolished (one is visible in the photograph), therefore Abberline would still have been at Leman Street.

The frustrations under which Monro was labouring peaked in 1885. On 2 January an underground train was bombed at Gower Street. On 24 January Monro was at Scotland Yard when he was told that a bomb had exploded in the chamber of the House of Commons and another at the Tower of London. Grabbing hold of Williamson he asked him to put out an all-ports alert and then go to Westminster while he, Monro, went to the Tower. The explosion there had been in a room below the armoury and the blaze had already been extinguished by the time of Monro’s arrival. Immediately after the bomb went off the Tower gates had been shut, and tourists and visitors had been held for security checks. Already on the scene was Inspector Abberline – the Tower was H Division’s responsibility – and he was questioning an Irish-American suspect. Dissatisfied with the man’s replies, he took him to Monro for further questioning. While the interview was taking place a succession of telegrams, three in all, arrived for Monro from an increasingly irate Home Secretary, Sir William Harcourt, who demanded the assistant commissioner’s immediate return to the Home Office. Monro ignored them until their increasingly hysterical tone forced him to comply. He hurried back to the Home Office only to discover that in his absence the home secretary had personally gone to Scotland Yard and sent fourteen of Monro’s detectives to the ports to watch for suspicious persons. In the assistant commissioner’s private opinion the man simply went ‘off his head’ whenever there was any talk of explosions. In Cabinet his violence of expression on one occasion led to the suggestion by a fellow minister that he seemed to want to expel all Americans including his wife. His hysteria was such that he had fifteen men front and back of his house to protect him as well as two plain clothes policemen.

Between them, Sir William Harcourt and Jenkinson drove Monro nearly frantic with their interference. Jenkinson was scathing of both Monro and Williamson, the former he thought had too little originality and the latter was ‘very slow and old fashioned’. At one point, in a sweeping denunciation of the Scotland Yard detectives, he even alleged corruption and the wholesale taking of bribes. He withheld, or would not exchange, information with Monro until eventually the home secretary had to threaten him with disobeying orders unless he told Monro what he knew. In 1888 Jenkinson’s role was ultimately reduced to a passive one and his Irish detectives sent home. The clash had been between two styles of policing: Monro and Williamson favoured the old Peelite style of preventive policing, similar to the role of the uniform police, where it was better to nip a scheme in the bud than allow it to become fully developed; Jenkinson favoured the spy system, which was the Irish method, allowing plans to become fully developed before closing in on them. At times the latter could be dangerously close to a system of agents provocateurs. Frequent changes of minister had allowed Jenkinson to continue his unjustifiable interference – they were never in office long enough to see how pernicious his system was.

More worrying was the continuing hostility of the press towards police generally. Criticism was not limited to the controversies of the police strike or the trial of the detectives but was part of a sustained campaign of general vilification. The policeman was pilloried ‘as a nincompoop, a figure of fun, or a downright brute. If he made a mistake it was reported at length, and probably made the subject of a leading article; if he did a good piece of work that was not news in those days.’4 Unfavourable comparisons were regularly drawn between Commissioner Henderson and his predecessor Sir Richard Mayne, who himself had been the target of a great deal of hostile criticism but who was now found to have virtues that had not always been recognised in his lifetime, and it was inevitable that sooner or later Henderson would be forced out of office. The campaign to oust him began on 8 February 1886 when small-scale rioting broke out in the West End of London. There were demonstrations in Trafalgar Square. A small mob broke away from the main meeting and marched through Pall Mall and St James’s (London’s clubland) to Oxford Street, hurling stones and breaking windows on the way. Henderson had been out in the square all day but the press reaction to his response was still hostile. A Punch cartoon showing a somnolent commissioner reclining in his office was labelled ‘The Great Unemployed’. The newly appointed Home Secretary, Hugh Childers, had no need for excuses to make Henderson the scapegoat for the riots on that ‘Black Monday’. Henderson knew it was inevitable that he would be ‘thrown over by the government’ and resigned before he could be dismissed.

A new commissioner was required. London was threatened from within and without by large-scale, working-class demonstrations and a continuing bombing campaign. A strong hand was needed to get a grip on the situation. Inevitably the choice was a military one.

When the Metropolitan police was formed in 1829, it was to be a police force for the whole of London with the glaring exception of the City of London. The square mile around St Paul’s Cathedral had been excluded as part of a political deal because of concerns about its ancient rights and privileges and fear of control passing from a democratically elected council, the most powerful in the country, to a minister of an unreformed Parliament. The consequences of this ill-judged separation, so it was said, would be that ‘Thieves would assemble in London as an asylum. When they threw a dog into the water, the fleas all got into the head to avoid drowning, and in the same way all the thieves would get into the City to avoid hanging.’ Not until 1839, ten years later, was the City to form its own police force of 500 men under the command of a commissioner with headquarters at 26 Old Jewry, close to the ancient Guildhall.

In 1863 Daniel Whittle Harvey, the City of London Police Commissioner, died. He had been the first commissioner and a controversial one. He was a Liberal Member of Parliament at the time of his appointment and had only taken up the position to relieve his debts. He was a powerful speaker and had expected to continue as an MP even after his appointment. It was too much for the government to have a police commissioner sitting in opposition and a clause was inserted into the City of London Police Act debarring the commissioner from having a seat in Parliament. Harvey was outraged but too far committed to withdraw and always said that he would never have applied to be commissioner had he known that such a rule would be passed. His time as commissioner was one of constant conflict with the City fathers and only relief was expressed when he died. His successor was a Scotsman, James Fraser, who had joined an English regiment at the age of 16, eventually rising to command it. He then exchanged to another regiment but seeing no prospect of active service had retired as colonel of the 72nd Foot less than a year before the Crimean War broke out in 1854. According to Henry Smith, who would eventually succeed Fraser as chief commissioner, he bitterly repented what he had done, for his decision was an irrevocable one, and he was unemployed for some months. In desperation, as the work was distasteful to him, he became governor of a female reformatory before successfully applying to be the chief constable of Berkshire where he spent some years before being appointed as Harvey’s successor as commissioner of the City of London Police. He was created a Companion of the Bath in 1869 and promoted to a Knight Commander in 1886.

‘The Great Unemployed’ – Sir Edmund Henderson, Metropolitan Police Commissioner, is shown in this Punch cartoon of 20 February 1886 reclining in his chair on 8 February 1886, the first day of the rioting.

One of the enduring myths of police history is the supposed conflict between the two London forces and especially between the two commissioners. The explanation given for the alleged friction by Henry Smith, who became Fraser’s deputy and then succeeded him as commissioner, was that on the death of Sir Richard Mayne, Sir George Grey sent for Fraser, who was then Chief Constable of Berkshire, and appointed him to the commissionership of the Metropolitan Police. Smith said Fraser returned to the congratulations of the county and was on his way to take up the appointment when he received a letter from the Home Office saying that there had been a change of mind and that Grey was appointing Colonel Henderson to the vacancy. Smith added that Fraser felt the injustice of his treatment very strongly but then within a few months gained the City appointment, which in some ways was a more desirable one. This account has often been put forward as a reason for Fraser to feel hostile towards the Metropolitan Police and as an explanation for why in a later incident, again told by Smith, he was prepared to turn back mounted Metropolitan policemen by force from the City boundary. The problem with the first part of the story is that Mayne died in 1868, five years after Fraser was appointed Commissioner of the City of London Police: Fraser could simply not have been appointed Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. As for the second part of the story, the idea that Fraser could have ordered Smith to the boundary with 200 City policemen to ‘stop by force, if necessary’ a Metropolitan-police-escorted procession from entering the City, with the possibility of a ‘free fight between the two police forces’, is too ludicrous even to consider.

Colonel Sir James Fraser, the 74-year-old City of London Police Commissioner, at the time of the murders. He had been in office since 1863 and retired in 1890, making way for Henry Smith.

Major Henry Smith, Acting Commissioner of the City of London Police at the time of the murders, was later promoted to commissioner. When the Mitre Square murder was committed Smith was ‘tossing about in his bed at Cloak Lane Station’; he was roused to join the hunt for the Ripper.

Henry Smith was born in 1835 and was 53 years old at the time of the Ripper murders. He had been educated at Edinburgh Academy and University and worked as a book-keeper until the death of his father. In 1869 he was commissioned in the Suffolk Artillery Militia but he was very much a social butterfly, first in London and then in Northumberland. London did not agree with his mother, which prompted a move in 1872 to Alnmouth on the coast of Northumberland. His mother died the following year but Smith kept the house on and stayed there for the next twelve years. His only employment during this time seems to have been the management of the local lifeboat. When he was not so engaged, his life seems to have been a social whirl of hunting, shooting and staying at friends’ houses for weeks at a time. One of his hunting friends, a former chief constable of Northumberland, asked this butterfly if he would like the job of chief constable because it was shortly to become vacant. Nothing would suit him better, Smith replied. Surprisingly (to him), he was not appointed to the post but his thoughts now turned to police work and he decided to prepare himself for another vacancy should one occur. A three-month stay with a Scottish chief constable (little work was involved) earned him a testimonial. This was followed by a month’s police work in Newcastle and with powerful backing he applied unsuccessfully for the post of detective superintendent in Liverpool. Somewhat crestfallen, Smith returned to Alnmouth where he received a letter from Major Bowman, Chief Superintendent, City of London Police, inviting him to the capital. At this time the chief superintendent was in effect the assistant commissioner of the force. Bowman told Smith that he was planning to retire and Smith would seem to be the sort of man that would suit the post. That was in 1879. In fact it was another six years before Bowman retired and Sir James Fraser made Smith his number two. Owing to his age, this was the only police appointment in Great Britain for which Smith was eligible. Those six years of waiting, said Smith, had been weary ones. He hunted, shot and played golf, but whenever he was summoned to the City to see Bowman he was ready to go. Quite shamelessly he called his autobiography From Constable to Commissioner.

About the same time as Smith’s appointment, Charles Warren was just recovering from his election defeat. For a half-pay officer, with no party backing, the costs would have been a heavy burden but the local Liberal Party was so delighted with his efforts that, knowing he had refused party funds to fight his campaign, raised a subscription on his behalf to pay off his election expenses.

Still unemployed, Warren now had more time for his Masonic interests.5 In January 1886 he was installed as first master of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge devoted to Masonic research. Shortly before the consecration of the lodge, Warren was astonished, in view of Wolseley’s threats, to receive a communication from the War Office telling him that he had been appointed to the Army Staff in Egypt with the local rank of major-general. He was amazed to be told that he had been recommended for the post by Wolseley. There were rumours that he was becoming something of a thorn in the side to Wolseley, but how it is not clear. The most obvious explanation for his appointment is that, although Warren was a failed Liberal candidate, the machinery of the party in government had swung behind him and quietly overruled Wolseley’s determination that Warren should never again be given a military appointment.

At Suakin, in early February, he found a garrison of mixed nationalities, British, Indian and Egyptian, which he swiftly reorganised. With the help of local Arabs they cleared a safety zone around the city and drove back inland the enemy Arabs who had been firing into Suakin every night. At Government House, Warren found that the servants and batmen were convicts, some murderers, on parole. Warren chose a well-known poisoner to make the coffee to serve to visitors and since, as host, he always had to drink the first cup, he made sure that he was preceded by the poisoner who had to taste the first brew.

However, within two months of taking up this appointment, Sir Charles was on his way back to England. The post of Metropolitan Police commissioner was vacant and there were over 400 applicants for the post. This list had been reduced to three officers and three civilians. Curiously Warren’s name seems to have been put forward without his being aware of it. Possibly his Liberal politics may have had some bearing upon his appointment as he and Home Secretary Hugh Childers were both staunch supporters of Gladstone and shared other interests in common besides politics. On 13 March 1886 he received a telegram from Childers offering him the vacancy. To his even greater astonishment, it seems that Wolseley had once again intervened on his behalf by recommending the 46-year-old soldier in preference to the other applicants. If this was Wolseley’s way of permanently removing Warren from the army, then Sir Charles must have been more of a thorn in the side than is generally supposed. The Pall Mall Gazette described his appointment as ‘the succession of King Stork to the throne of King Log’.

One of the more curious anecdotes Warren told of his time excavating in Palestine is about a recurring nightmare that might be interpreted as a warning of things to come in his future appointment as head of the Metropolitan Police. Not surprisingly it generally followed a late heavy supper:

I have now and then been visited by the unwelcome intruder, which usually, on these occasions, took the form of my being surrounded in a defile and attacked hand to hand: invariably it was attended with the same result; my revolver never missed fire, my cudgel never swerved from the head of my victims, one after another they were shot down or laid low, until, flushed with victory, I would awake, pleased to have done my duty towards my fellow-men, and in a healthy glow settle to sleep again, feeling all the better for my supper and at peace with the world. It was not only when well-guarded that my dreams took such a pleasant course, it was just the same when among thievish villages with no other companion than the cook, the muleteers having gone to a more secure place; and again it was the same when in a tent on a lonely spot the west of Jerusalem, the reputed haunt of thieves there, where even my servant left me and my little dog disappeared, I tucked my clothes under the mattress to prevent their being stolen, buckled my revolver round my night-shirt and slept as pleasantly as though I had been in the most secure position. The insecurity of this spot was so well known that I was urgently advised to come into the hotel: I had no sooner done so than all my combats were reversed in their results. The revolver would not go off, my club hung in mid-air, I was cudgelled by my assailants and slain over and over again. It was ever the same with me, I slept miserably in thick-walled houses but happily in a tent.6

Looking back to his postings as a colonial administrator, to Griqualand and Bechuanaland, the Sinai Peninsular and Suakin, postings where he could act independently, and because of the distances involved, unchecked by the hand of authority, and where his on-the-spot decisions and actions could go unchallenged, it would seem clear that any job that limited this freedom and independence of action might provoke a violent reaction. The contrast in his dream between the country and the city could hardly be clearer. By 1886 he had been untrammelled by authority for nearly two decades. That he would be determined to have his own way in anything he did is clear from his autobiographical Underground in Jerusalem. His instructions from the Palestine Exploration Fund were that he was to excavate around the Temple Mount but a vizierial letter forbade such work: ‘yet in the teeth of this letter, in direct opposition of the Pacha’s order, and contrary to the advice of the Consul’ and entirely contrary to the wishes of the local Muslims he persisted. A native said his words were like pebbles, smooth and hard. Warren’s attitude to officialdom can best be witnessed in his relations with Nazif Pacha, the Governor of Jerusalem; Warren admitted that he was ‘constantly under the necessity of acting in opposition to his wishes and pushing my way in spite of efforts to restrain me’. Warren’s object was never ‘simple opposition, it was pressure continued until my adversary began to yield, and then when he felt he must give way, endeavour to make arrangements by which he should have the appearance of bestowing gracefully, and this before he should feel bitterly disposed by the prospect of the exposure of his failure’.

Sir Charles Warren, Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police at the time of the murders in 1888. Many of the letters were addressed personally to him.

Such insistence on having his own way was bound to cause resentment and provoke controversy. It is a pattern of behaviour which reappeared again and again throughout his career – in Jerusalem in 1869, with Lord Wolseley in 1885, with the home secretary in 1888, and with Sir Redvers Buller in the Boer War. When he was made Metropolitan Police commissioner, controversy seemed inevitable from the beginning. In the cockpit of Whitehall and Whitechapel, Warren’s quarrels with his political masters and troublesome subordinates might have been foreseen.