THE second victim of 30 September 1888 was Catherine Eddowes of 55 Flower and Dean Street, another common lodging house. She also used the names Kelly (her current man-friend was John Kelly) and Conway (her ex-common-law husband was Thomas Conway). Catherine was a native of Wolverhampton and was born to George Eddowes, a tinplate worker, and his wife Catherine (née Evans) on 14 April 1842. She was one of eleven children. John Kelly was described as ‘a peculiar looking man … of perhaps 40 years, with a fresh coloured face, bronzed by a recent hop-picking excursion, a head of thick black hair, a somewhat low forehead, and moustache and imperial. He wore the fustian clothes of a market labourer with a deep blue scarf round his neck, and spoke with a clear, deep, sonorous voice.’1

John Kelly and Eddowes had been hop picking in Kent up until Thursday 27 September. They both slept in the casual ward at Shoe Lane that night.2 On Friday she found a bed in the casual ward at Mile End, while Kelly slept at 55 Flower and Dean Street. Kelly saw Eddowes next at 8 o’clock on Saturday morning. They had some tea and coffee, bought after he pawned the boots he stood in. Kelly last saw Eddowes alive at 2 p.m. that day in Houndsditch. They had no money to pay for their lodgings and she told him that she was going over to Bermondsey to see her daughter Annie (whose father was Conway) with a view to getting some money. She said she would be back by 4 p.m. but did not return. Kelly was later told by two women that Eddowes had been locked up in Bishopsgate for ‘a little drop of drink’. He checked that she would be out on Sunday morning. In his statement to the police Kelly admitted that she was ‘occasionally in the habit of slightly drinking to excess’ but he made a point of saying that he ‘never suffered her to go out for immoral purposes’ – ‘She has never brought money to me that she has earned at night.’ This seems to indicate that he was anxious to avoid accusations that he was a pimp. However, when giving his evidence at the inquest on 4 October, Kelly stated that Eddowes was trying to borrow money so that ‘she need not walk the streets’. Mr Crawford, the City solicitor, pointed out that Kelly had said that she did not walk the streets. Kelly then admitted that they were short of money at that time, virtually implying that she was indeed ‘walking the streets’, i.e., engaging in casual prostitution; see The Times, 5 October 1888.

A contemporary likeness of Catherine Eddowes that appeared in the Penny Illustrated Paper of 13 October 1888.

Frederick William Wilkinson, the deputy of their lodging house at 55 Flower and Dean Street, told police that the pair lived as man and wife. He said he had known them for the past 7 or 8 years and added that she had made a living by hawking ‘about the streets’ and cleaning for Jews. They had paid their rent pretty regularly. Eddowes did not drink often, he said, and she was a ‘very jolly woman’. Wilkinson last saw her alive, with Kelly, between 10 and 11 a.m. on Saturday 29 September. He made a point of saying, ‘I did not know her to walk the street. I never knew or heard of her being intimate with any one but Kelly. She used to say she was married to Conway and her name was bought and paid for.’ Wilkinson said that Kelly had returned to the lodging house between 7.30 and 8 p.m. and he had asked him ‘Where’s Kate?’ to which Kelly had replied, ‘I have heard she’s been locked up.’ The records show Eddowes was not arrested until 8.30 p.m., so Wilkinson’s timing was incorrect – Kelly must have returned after 8.30. Kelly took a single bed for 4d, half the price of a double. It had been four or five weeks since Kelly or Eddowes had slept at Wilkinson’s because they had been away hopping. Wilkinson told police he was positive Kelly did not go out again that night.

At 8.30 p.m. on Saturday 29 September PC 931 Louis Robinson of the City Police was on patrol in Aldgate High Street when he saw a crowd of people outside no. 29. He went to investigate and found a woman, later identified as Eddowes, lying on the footway, drunk. He asked if anyone knew her or where she lived but received no reply. Robinson picked her up and carried her to the side of the path near the shutters. She fell sideways so he sought help from another officer to deal with her. She was taken to Bishopsgate Street police station, arriving at 8.45 p.m. They were seen by the Station Sergeant, James Byfield. At this time Eddowes was supported by the two constables. She was asked for her name and replied, ‘Nothing.’ She smelt very strongly of drink.

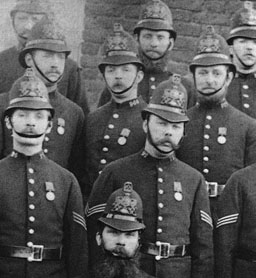

John Kelly, who had lived with Catherine Eddowes as her common law husband for seven years. She often adopted his surname, as well as that of her ex-partner Tom Conway.

Bishopsgate police station, c. 1910.

Prisoners brought into the station for drunkenness were not searched but a handkerchief or anything else they could use to injure themselves was taken from them. This is in stark contrast to modern practice where all prisoners admitted, whatever the offence, are thoroughly searched and their property taken from them and noted down. From a list of the property later found on Eddowes’ body, we know she was carrying a handkerchief, a table knife and needles and pins (among other things) but we don’t know whether these were taken from her at the police station. She was placed in a cell. Robinson last saw her in the cell at 8.50 p.m. and noted that she was wearing an apron.

PC 968 George Henry Hutt came on duty as gaoler at 9.45 p.m. He saw Eddowes who was then asleep. Hutt visited her about every 30 minutes from 9.55 p.m. At 12.15 a.m. she was awake and singing to herself. At 12.30 she asked Hutt when she was going to be let out. He replied, ‘When you are capable of taking care of yourself.’ She said that she was then quite up to taking care of herself. At 12.55 a.m. Hutt decided she was sober. She was then taken from the cell and asked Hutt what time it was. Hutt said, ‘Too late for you to get any more drink.’ She replied, ‘Well what time is it?’ He said, ‘Just on one.’ She said, ‘I shall get a damned fine hiding when I get home.’ Hutt replied, ‘And serve you right, you have no right to get drunk.’

They then went to the office where, at 1 a.m., Byfield agreed she was sober. (It was usually left to the discretion of the inspector, or acting inspector to decide when a drunk was in a fit condition to be discharged.) She gave her name and address as Mary Ann Kelly, 6 Fashion Street, Spitalfields, and said that she had been hopping. Byfield discharged her. Hutt pushed open the swing door leading to the passage and said, ‘This way, Missus.’

She passed along the passage and to the outer door. Hutt asked her to pull it after her. She said, ‘All right. Good night, old cock.’ She went out, pulling the door to within 6 inches of closed and turned left in the direction of Houndsditch.

Like Robinson, Hutt noticed that she was wearing an apron. At the inquest he estimated that it would have taken her about 8 minutes, walking at an ordinary speed, to get to Mitre Square.

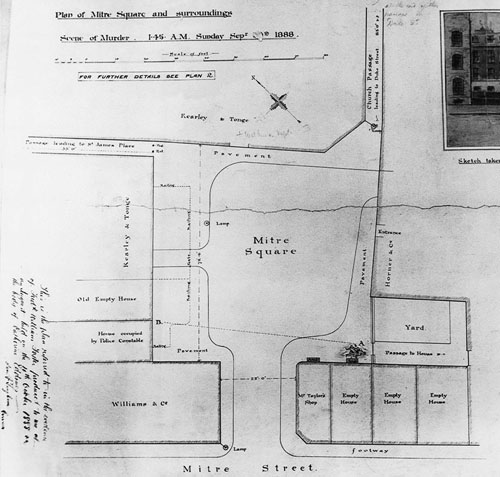

Since August 1888 the City commissioner had put out extra night patrols in plain clothes to police the eastern area of the City, hoping to prevent further murders and to keep close observation on all prostitutes frequenting public houses and walking the streets. At 1.30 a.m. PC 881 Edward Watkins, a seventeen-year veteran of the City Police, passed through Mitre Square, Aldgate, on his beat; all was quiet and in order. He returned 14 minutes later, entering the square from Mitre Street. Turning right into the gloomiest corner of the square, the south one, Watkins shone his bull’s-eye lantern and instantly saw a woman lying on her back, her feet towards him. It was Catherine Eddowes, so recently released from police custody in Bishopsgate Street.

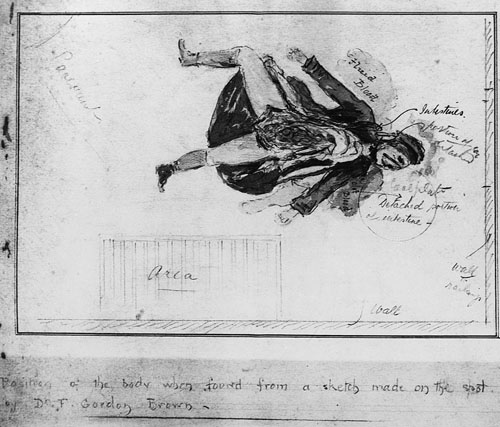

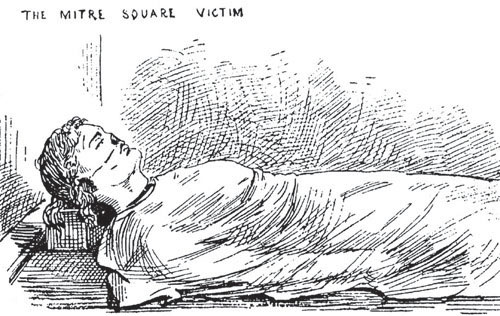

Her throat was deeply cut, her clothing shredded and thrown open, exposing her abdomen which had been opened up from the pubic area to the sternum. Her head was turned to her left, towards the wall of a house, and she was lying in a pool of liquid blood. Her arms were by her sides, spread out slightly away from her body, palms upward and fingers slightly bent. A 2-foot piece of intestines had been detached and was lying on the ground between her body and her left arm, apparently deliberately placed there. More intestines, smeared with feculent matter, were draped up from the abdominal cavity and over the right shoulder. There were also various cuts on her face. The lobe and auricle of the right ear were cut obliquely through. She presented a ghastly spectacle that shocked Watkins. He immediately ran to the east side of the square where the door to Kearley & Tonge’s warehouse stood slightly ajar. The nightwatchman, 54-year-old George James Morris, an ex-Metropolitan Police officer, was inside, sweeping the steps down to the door. It had been ajar only 2 or 3 minutes, according to Morris, when Watkins pushed it open.

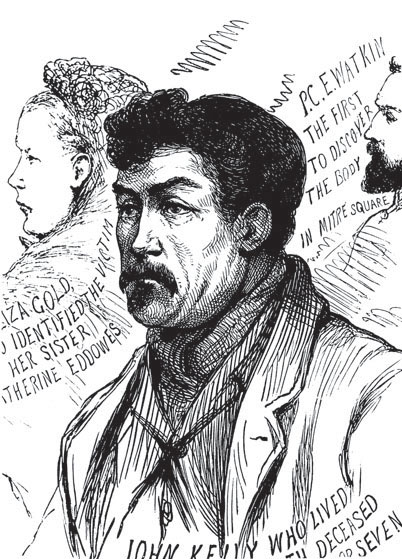

55 Flower and Dean Street, where Catherine Eddowes lodged with John Kelly. If she had returned here on her release from Bishopsgate police station she would not have met the Ripper that night.

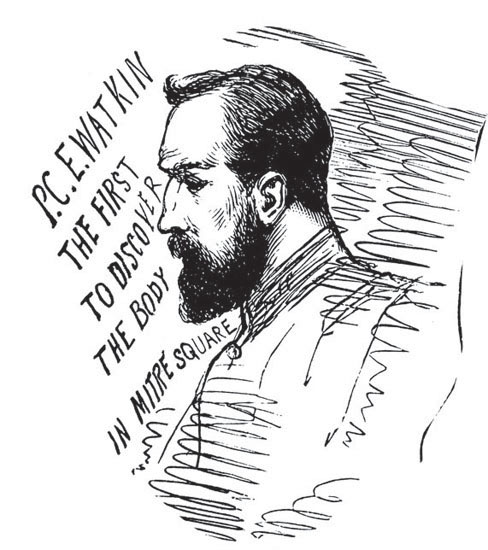

PC 881 Edward Watkins of the City of London Police. He discovered the body of Catherine Eddowes in Mitre Square.

A contemporary drawing of the scene of the Eddowes murder.

A contemporary drawing of the victim’s body at the murder scene.

Mitre Square. The door at the far right (open at the time of the murder) led into Kealey & Tonge’s warehouse where the warehouseman, George Morris, was sweeping the floor.

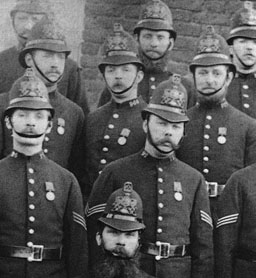

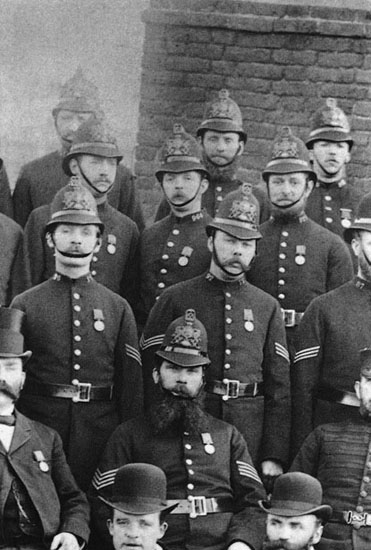

An enlargement of a detail from a City of London Police group photograph shows PC 964 James Harvey (middle of second row of three from top). He was almost certainly the police officer who came closest to catching the Ripper red-handed, in Mitre Square at 1.40 a.m. on Sunday 30 September 1888.

Mitre Square, Aldgate, looking west towards the corner where Eddowes’ body was discovered. Mitre Street can be seen through the gap in the buildings. This photograph was taken from a spot just in front of where PC Harvey must have turned at the bottom of Church Passage while the Ripper was undoubtedly in the square with his victim.

Watkins said, ‘For God’s sake, mate, come to my assistance.’ Watkins was so agitated that Morris thought he might be ill. Morris asked what was the matter and Watkins said, ‘There is another woman cut to pieces.’ She had been ripped up like ‘a pig in a market’, he said, and her entrails ‘flung in a heap about her neck’. Morris took his lamp and looked at the body, then ran up Mitre Street towards the main road blowing his whistle for assistance. He was soon joined by two police constables whom he sent to Mitre Square. One of them was PC 964 James Harvey. Morris followed and returned to the warehouse. He said he had neither heard nor seen anything prior to Watkins’ arrival.

PC Harvey said he had been down the narrow Church Passage as far as Mitre Square at about 1.40 a.m. and had seen and heard nothing untoward. He returned up the passage and back into Duke Street. There is no reason to suppose that Harvey shone his lamp into Mitre Square nor even took much notice of it because the area was PC Watkins’ responsibility. However, when Harvey’s account is combined with evidence from three Jewish witnesses located by later house-to-house inquiries, it seems the murder was committed after 1.35 a.m. (when the Jewish men passed by) and before 1.45. The murderer and his victim were probably already in the square as PC Harvey turned at the bottom of Church Passage and retraced his steps. He had been within yards of catching the killer literally red-handed. It was very shortly after 1.45 that Harvey responded to Morris’s whistle in Aldgate.

Detective Constables Daniel Halse and Edward Mariott, and Detective Sergeant Robert Outram, had been engaged in the immediate neighbourhood, searching the passages of houses where doors were left open all night. After hearing of the murder at about 1.55 a.m. they set off in various directions to search for suspects. Halse went towards Whitechapel via Middlesex Street and then into Wentworth Street where he checked two men. He then passed through Goulston Street at about 2.20 a.m., saw nothing and returned to Mitre Square.

Sketch plan of the murder site in Mitre Square on 30 September 1888, the night of the ‘double event’. Catherine Eddowes’ body is in the southern corner marked ‘A’. The sketch was prepared by Frederick W. Foster, the City Surveyor.

A few private houses in Mitre Street backed on to the square’s south corner. On the north-west corner of the Square, no. 3, was occupied by a City of London Police Constable, PC 922 Richard Pearce, who had retired to bed at 12.30 a.m. He heard nothing until he was called by a fellow officer at 2.20 a.m. and informed of the murder. The murder site was visible from his window. No. 5 Mitre Street was occupied by George Clapp who was caretaker of the premises. He and his wife had gone to bed at 11 p.m. and their bedroom, on the second floor, also overlooked the murder site. They heard nothing of the attack until between 5 and 6 a.m. At 3 a.m. the police checked the lodging house at 55 Flower and Dean Street.

The three Jewish witnesses already mentioned had been at the Imperial Club, 16–17 Duke Street, Aldgate, that night. They were Joseph Lawende, a 41-year-old commercial traveller in cigarettes of 45 Norfolk Road, Dalston; Joseph Hyam Levy, a 47-year-old butcher of 1 Hutchinson Street, Aldgate; and Harry (Henry) Harris, a furniture dealer of Castle Street, Whitechapel. At 1.30 a.m. they decided to leave the Imperial Club and actually departed the building at 1.35. It was raining. Lawende walked a little distance from the others. He noticed a man and a woman apparently conversing quietly on the opposite side of the road. They were about 30 feet away at the corner of Church Passage, 30 yards or so from Mitre Square. The spot was badly lit. The woman, who appeared to be about 5 feet tall, had her back to Lawende and he did not see her face, although he did notice that she was wearing a black jacket and a black bonnet. Her hand was on the man’s chest. Lawende also said that, despite the description he gave, he doubted whether he would know the man again. The police also noted that the identification of the woman as Eddowes was by her clothes only, which Lawende later saw at the mortuary, and this was a ‘serious drawback to the value of the description of the man’. However, as the body of Eddowes was found in Mitre Square 10 minutes later, the police thought it ‘reasonable to believe that the man he saw was the murderer’. Lawende passed by on the opposite pavement without looking back.

Levy thought he and his friends had left the club about 1.33 or 1.34 a.m. and he too saw the man and woman standing at the corner of Church Passage. He said to Harris, ‘Look there, I don’t like going home by myself when I see those characters about.’ Later, in answer to a question from the coroner, Levy said there was nothing about the man and woman which caused him to fear them and added he had not said he feared for his safety. He took no further notice of them, thinking that ‘persons standing at that time in the morning in a dark passage were not up to much good’. He thought the man was about 3 inches taller than the woman but noticed nothing else. He walked on along Duke Street and into Aldgate, reaching home by 1.40 a.m. Levy was not used to being out so late at night – he said he was usually home by 11 p.m. – and it must have been fairly apparent that the two were prostitute and client, which probably explains his concern. Although Harris also saw the couple the police did not deem it necessary for him to give evidence at the inquest, so we must assume that he noted less than his companions.

The City night duty inspector, Edward Collard, was in charge of the division. He was at Bishopsgate Street police station when he received news of the Mitre Square murder at 1.55 a.m. He telegraphed the information to headquarters at 26 Old Jewry and sent a constable for the City Police surgeon, Dr Frederick Gordon Brown of 17 Finsbury Circus. Collard then made his way to Mitre Square, estimating that he arrived at 2 or 3 minutes past 2 a.m. Several police officers were there along with Dr George William Sequeira. The body was not touched until Dr Brown arrived at about 2.18 a.m. There was no sign of a struggle at the scene. Sergeant Jones picked up three small black buttons of the kind used on women’s boots, a small metal button, a metal thimble and a small mustard tin containing two pawn tickets. He found these objects at the left side of the body and handed them to Collard. The body was examined. It was quite warm and there was no rigor mortis. The doctor found no bruising, no secretion of any kind on the thighs, and no spurting of blood on the bricks or surrounding pavement. There was no blood on the front of the clothes and no traces of recent sexual intercourse.

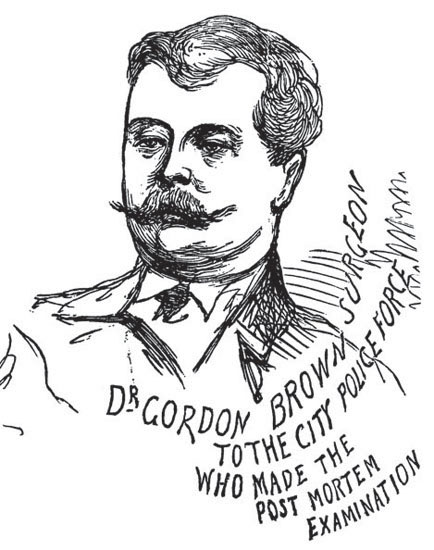

Dr Gordon Brown, City of London Police surgeon and the doctor who examined Catherine Eddowes and the ‘Lusk kidney’.

Eddowes was wearing a loosely tied black straw bonnet trimmed with green and black velvet. It had partially fallen from the back of her head and was lying in a pool of blood that had run from her neck. She had a black cloth jacket with imitation fur round the collar and sleeves and two outside pockets trimmed with black silk braid and imitation fur. A large quantity of blood was found inside the jacket, which was very dirty and bloody on the back. Eddowes also wore a chintz skirt with three flounces and a brown button on the waistband. This had a jagged 6½-inch cut from the left side of the front of the waistband. The edges of the cut were slightly bloodstained and there was blood on the bottom, front and back of the skirt. She had a brown linsey dress bodice with a black velvet collar and brown metal buttons down the front; there was blood inside and outside the back of the neck and shoulders and a clean 5-inch cut at the bottom of the left side, running from right to left. She wore a grey stuff petticoat with a white waistband which bore a 1½-inch cut with bloodstained edges in front. There were bloodstains on the front of the petticoat at the bottom. Eddowes also had a very old green alpaca skirt with a 10½-inch jagged cut made downwards through the front of the waistband. The garment was bloodstained inside under the cut. In addition, Eddowes had a very old, ragged blue skirt with a red flounce and a light twill lining. It had a 10½-inch jagged cut downward through the waistband and was bloodstained inside and out on the front and back. She had a white calico chemise which was bloodstained all over and cut in a zig-zag in the middle at the front. She also wore a man’s white vest with buttons down the front and two outside pockets. It was torn at the back and there were blood and other stains on the front. She was wearing no drawers or stays. She had men’s lace-up boots with mohair laces; the right one had been repaired with red thread and bore six blood marks. On her neck was a piece of red gauze silk which had various cuts in it. She also had a bloodstained white handkerchief; two unbleached calico pockets with tape strings which had been cut through – the top left-hand corner had been removed from one; one bloodstained, blue-striped, bed-ticking pocket with the waistband and strings cut; a white cotton pocket handkerchief with a red-and-white bird’s-eye border; a pair of brown ribbed stockings, the feet mended with white thread; twelve pieces of white rag, some bloodstained; a piece of coarse white linen; a three-cornered piece of blue-and-white shirting; two small blue bed-ticking bags; two short black clay pipes; two tin boxes, one containing tea and the other sugar; a piece of flannel and six pieces of soap; a small-tooth comb; a white-handled table knife; a metal teaspoon; a red leather cigarette case with white metal fittings; an empty tin matchbox; a piece of red flannel containing pins and needles; a ball of hemp and a piece of old white apron.

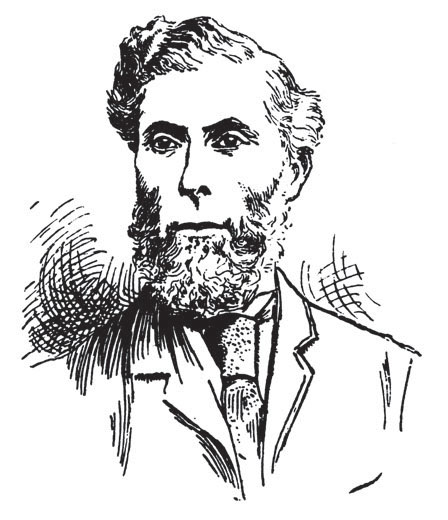

Inspector James McWilliam, head of the City of London Police Detective Department. He led the investigation into the Mitre Square murder.

An ambulance arrived to take the body to Golden Lane mortuary. Collard ordered the neighbourhood searched. Detective Inspector James McWilliam, head of the City detectives, arrived shortly afterwards with a number of men who were detailed to search streets and lodging houses. Several people were stopped and searched but without result. Later, many people flocked to Mitre Square to satisfy their morbid curiosity. Inspector Izzard, and Sergeants Phillips and Dudman were there to keep the crowds in order.

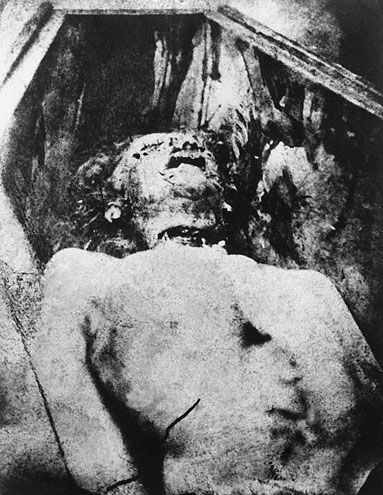

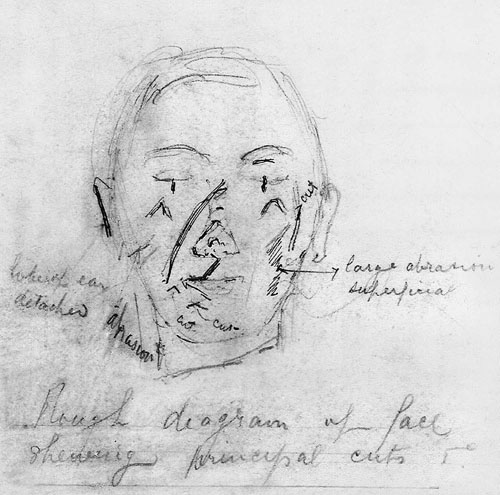

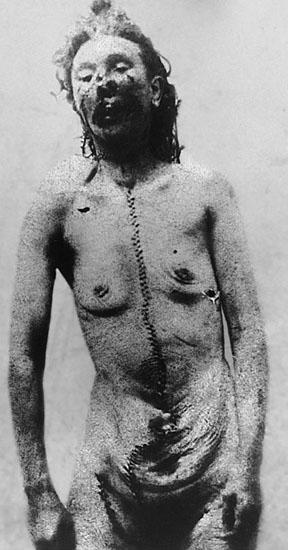

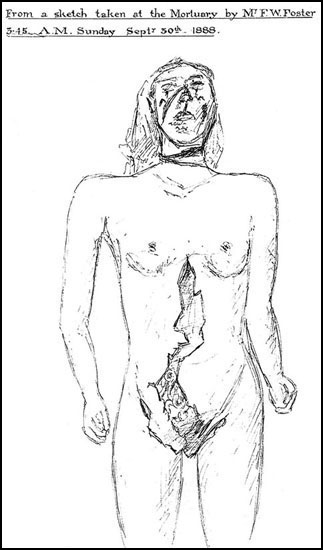

At the mortuary the body was carefully stripped and the property listed. A piece of Eddowes’ ear dropped from the clothing. There was a portion of the apron which was cut through and the woman had apparently been wearing it on the outside of her dress. Dr Brown performed the post-mortem examination at 2.30 p.m. on Sunday 30 September in the presence of Dr Sequeira, Dr William Sedgwick Saunders (the City Public Analyst) and Dr Phillips. Brown recorded that rigor mortis was ‘well marked’ but the body was not quite cold. There was a green discolouration over the abdomen. When he washed the victim’s left hand Brown found a recent red bruise the size of a sixpence on the back between the thumb and first finger. There were old bruises on the right shin. The hands and arms were bronzed by the sun. There was a ¼-inch cut through the lower left eyelid, dividing the structures completely. On the upper left eyelid there was a scratch through the skin near to the angle of the nose. The right eyelid was cut through to about ½ inch. There was a deep cut over the bridge of the nose, extending from the left border of the nasal bone down across the right cheek to near the angle of the right jaw. This cut was so deep that it went into the bone and divided all the structures of the cheek except the mucous membrane of the mouth. The tip of the nose was detached by an oblique cut from the bottom of the nasal bone to where the wings of the nose joined the face.3 This incision also divided the upper lip and cut through the gum over the right upper incisor. There was a cut on the right angle of the mouth which appeared to be made by the point of a knife and extended 1½ inches parallel with the lower lip. Cuts on each cheek peeled up the skin and formed a triangular flap of about 1½ inches. On the left cheek there were two abrasions to the epithelium (the outer layer of skin). There was a little mud on the left cheek and two slight abrasions to the thin tissue under the ear. There was a 6- or 7-inch wound across the throat. A superficial cut began about 1½ inches below the left earlobe and about 2½ inches behind it, running across the throat to about 3 inches below the right ear. The big muscle across the throat was divided on the left and the large vessels on that side of the neck were severed. The larynx was cut below the vocal chords and all the deep structures were severed to the bone – the knife had marked the intervertebral cartilage. The sheath of the vessels on the right side was just opened and the carotid artery was pierced by a fine hole. The internal jugular vein was opened 1½ inches but was not divided. The vessels contained clotted blood. All the injuries, it was reported at the inquest, had been ‘performed by a sharp instrument, like a knife, and pointed’. The cause of death was haemorrhage from the left common carotid artery. Death was immediate and the mutilations were inflicted afterwards. Brown believed the wounds on the face were made to disfigure the corpse.

The abdomen had been ripped open with a jagged cut from the pubes to the breast bone. The cut began opposite the ensiform cartilage (the pointed base of the sternum) and went upwards; it divided the cartilage but did not penetrate the skin over the sternum. The knife must then have cut obliquely at the expense of the front surface of the cartilage. Behind it the liver had been stabbed, apparently by the point of a knife. There was another incision in the liver measuring 2½ inches and below this the left lobe of the organ was slit by a vertical cut. Two cuts were indicated by a jagging of the skin on the left side. The abdominal walls were divided in the middle line to within ¼ inch of the navel. The cut then took a horizontal course for 2½ inches towards the right side. Next it passed round the left side of the navel and made a horizontal incision parallel to the previous one, leaving the navel on a ‘tongue’ of skin. Attached to the left side of the navel were 2½ inches of the lower part of the rectus muscle. The incision then ran obliquely to the right and down the right side of the vagina and rectum, ending ½ inch behind the rectum. A stab wound on the left groin measured about 1 inch. It had been made by a pointed instrument. Below it was a cut of approximately 3 inches through all the tissues: this wound had damaged the peritoneum to about the same extent. An inch below the crease of the thigh, a cut extended from the front spine of the pelvic bone obliquely down the inner side of the left thigh. It separated the left labia and formed a flap of skin up to the groin. The left rectus muscle was not detached. A flap of skin was formed from the right thigh and the right labia; this extended up to the spine of the pelvic bone. The muscles that meet the poupart’s ligament on the right were cut through. The skin was retracted through the whole of the cut in the abdomen but the vessels were not clotted, nor had there been any appreciable bleeding.

Catherine Eddowes.

Catherine Eddowes.

An artist’s impression from the Pictorial News, Saturday 6 October 1888, of the body of Catherine Eddowes lying in the mortuary. It shows the nose was severed as well as the throat cut.

Catherine Eddowes, a police photograph.

Mortuary photograph of the body of Catherine Eddowes discovered by Donald Rumbelow in ‘the filthy attic room’ at Snow Hill police station in the 1960s. This was one of a set taken of the body for the City Police.

Brown removed the contents of the stomach and placed them in a jar for further examination. There seemed to be very little food or fluid in the stomach, but some partly digested farinaceous food escaped from the cut end. To a large extent the intestines had been detached from the mesentery (the tissue that attached them to the wall of the abdomen). About 2 feet of the colon was cut away. The curved end of the S-shaped part of the large intestine, where it leads into the rectum, was invaginated, or folded back on itself, very tightly into the rectum. The right kidney was pale and bloodless and there was slight congestion of the base of the pyramids (part of the internal structure of the kidney). There was one cut from the upper part of the slit on the under surface of the liver to the left side and another at right angles to this; both incisions were about 1½ inches deep and 2½ inches long. The liver was healthy and the gall bladder contained bile. The pancreas was cut, but not right through, on the left side of the spinal column. A piece of the lower edge of the spleen measuring 3½ inches by ½ inch was attached only to the peritoneum. The peritoneal lining was cut through on the left side and the left kidney had been carefully taken out, the left renal artery being severed. Dr Brown felt that someone who knew the position of the kidney must have done this. The membrane over the uterus was cut through and the womb was divided horizontally, leaving a 3/4-inch stump. The rest of the womb had been taken away with some of the ligaments. The vagina and cervix were uninjured. The bladder was healthy and uninjured; it contained 3 or 4 ounces of water. There was a tongue-like cut through the front wall of the abdominal aorta. The other organs were healthy. There were no indications of sexual intercourse.

Sketch of the body of Catherine Eddowes, drawn by Frederick W. Foster, the City Surveyor, for the inquest.

Dr Brown believed that the first wound was to the throat and that Eddowes must have been lying on the ground when it was inflicted. The injuries to the face and abdomen were inflicted with a sharp, pointed knife, the abdominal wounds indicating that it must have been 6 inches long. Brown also felt that the perpetrator must have had ‘considerable knowledge of the position of the organs in the abdominal cavity and the way of removing them’. It required a great deal of knowledge to know where the kidney was located and how to remove it. Such knowledge might be possessed by someone in the habit of cutting up animals, he said. The fact that the lower eyelids had been nicked indicated to Dr Brown that the killer had time to carry out the attack and that the whole act took about 5 minutes. He was certain there had been no struggle and that only one offender had been involved. The throat had been so instantly severed that the victim can have made no noise. He did not think that the perpetrator would have much blood on him. Dr Brown concluded that the abdominal cut had been made after death and that there would not have been much blood on the murderer. He said that when the murderer made the cut he was kneeling on the victim’s right side (that is on the side away from the house wall) and below the middle of the body.

Brown’s attention was drawn to a piece of apron – a corner of the garment with a string attached and bearing blood spots of recent origin. It was impossible to say whether the blood was human.4 Brown had seen another portion of apron, produced by Dr Phillips, that was found in Goulston Street and was marked with blood and what seemed to be faecal matter. He fitted the two together and their seams corresponded; the pieces also matched at a repair where a new section of material had been sewn in.

Dr George William Sequeira agreed with the evidence given by Dr Brown at the inquest.5 He added that he knew the locality and although the corner of Mitre Square in question was its darkest, there would have been sufficient light for the perpetrator to commit the deed. When questioned by the coroner, he said he did not think that the murderer had any design on any particular organ or that he was possessed of any great anatomical skill. He did not think that the offender would necessarily have been spattered with blood.

Dr William Sedgwick Saunders of 13 Queen Street, Cheapside, the Public Analyst for the City of London, examined the stomach contents. He was especially looking for narcotic poisons but the results were negative. Like Dr Sequeira, he said he believed the murderer had no significant anatomical skill and was not looking for a specific organ. It seems odd that both Sequeira and Saunders should come to this conclusion when the left kidney and part of the womb were taken away by the murderer. Some excellent crime scene drawings and plans of the Mitre Square murder were prepared for the inquest by the City Surveyor, Frederick Foster. These are preserved at the Royal London Hospital.

Eddowes’ daughter, Annie Phillips, aged 23, of 12 Dilstone Grove, Southwark Park Road, gave evidence to the inquest. She said she had not seen her father Thomas Conway for ‘15 or 18 months’. She described him as a teetotaller and reported that he had been on bad terms with Eddowes because she drank so much and had left her on account of this some 7 or 8 years previously. She had seen her mother frequently and Eddowes was in the habit of asking her for money. She said Conway was aware that Eddowes was living with Kelly.

The police felt that the three Jewish witnesses had probably seen the murderer. Lawende was required to treat his evidence as confidential until he appeared at the inquest. The same would have been true of Levy but Harris was not called, so he was probably not under the same restriction. That the police believed Lawende had seen the most, and could probably describe the murderer, is clear from the fact that the force paid all his expenses. According to the Evening News of 9 October:

one if not two detectives are taking him about.… Mr. Joseph Levy is absolutely obstinate and refuses to give the slightest information. He leaves one to infer that he knows something but that he is afraid to be called on the inquest. Hence he assumes a knowing air. The fact remains, however, that the police, in imposing their idiotic secrecy, have allowed a certain time to elapse before making the partial description these three witnesses have been able to give public, and thus prevent others from acting upon the information in the event of the murderer coming under their notice.

Because it was proving difficult to obtain information from Lawende and Levy, the keen representatives of the Evening News approached Harris and found him more communicative. However, he was merely of the opinion that neither Lawende nor Levy saw anything more than he did, ‘and that was only the back of the man’.

Some researchers and writers have read a great deal into police treatment of the three witnesses and have suggested that one of them, probably Levy, was able to recognise the man, or even knew him.6 There is little reason to believe they knew or saw anything more than their statements indicate. The secrecy and ‘knowing air’ the frustrated press encountered in Levy was probably little more than self-importance.

Lawende gave his testimony on 5 October and Mr Henry Crawford, the solicitor for the City Police, asked that the details he gave of the suspect’s description be withheld. However, the police had already issued a brief description of the man which appeared in The Times of 2 October: ‘He was described as of shabby appearance, about 30 years of age and 5ft 9ins. in height, of fair complexion, having a small fair moustache and a cap with a peak.’

Perhaps one of the most controversial aspects of the Eddowes murder was the subsequent discovery of the freshly soiled section of her apron and some chalked writing at the entrance to a tenement building in Goulston Street. PC 254A Alfred Long had been seconded from Whitehall to supplement H Division, so he was patrolling an unfamiliar beat. He stated:

I was on duty in Goulston Street on the morning of 30th September at about 2.55 a.m. I found a portion of an apron covered in blood lying in the passage of the door-way leading to nos. 108 to 119 Model Dwellings in Goulston Street.

Above it on the wall was written in chalk ‘The Juews are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.’ I at once called the PC on the adjoining beat and then searched the stair-cases, but found no traces of any person or marks. I at once proceeded to the station, telling the PC to see that no one entered or left the building in my absence. I arrived at the station about 5 or 10 minutes past 3, and reported to the Inspector on duty finding the apron and the writing.

The Inspector at once proceeded to Goulston Street and inspected the writing.

From there we proceeded to Leman Street, and the apron was handed by the Inspector to a gentleman whom I have since learnt is Dr. Phillips.

I then returned back on duty in Goulston Street about 5.

It was here that the controversy began. There can be no doubt that Warren’s decision to erase the writing caused much consternation and provoked much criticism, but what did the message mean? Had it in fact been written by the murderer – this could never be satisfactorily proved – or was it just a piece of fresh street graffiti.

Initial controversy was sparked by the question of why Warren, who attended the scene, did not wait for the message to be photographed but instead approved Superintendent Arnold’s suggestion that it be erased immediately. Arnold, on his first day back after a month’s leave, mentioned it in his own report:

my attention was called to some writing on the wall of the entrance to some dwellings No. 108 Goulston Street Whitechapel which consisted of the following words ‘The Juews are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.’ and knowing that in consequence of a suspicion having fallen upon a Jew named ‘John Pizer’ alias ‘Leather Apron’ having committed a murder in Hanbury Street a short time previously a strong feeling existed against the Jews generally and as the Building upon which the writing was found was situated in the midst of a locality inhabited principally by that Sect I was apprehensive that if the writing were left it would be the means of causing a riot and therefore considered it desirable that it should be removed. having in view the fact that it was in such a position that it would have been rubbed by the shoulders of persons passing in & out of the Building.

One of the most enduring and elaborate of the Ripper fantasy theories involves a royal/masonic conspiracy. A royal connection with the crimes was suggested in the 1960s and developed in the 1970s to involve Freemasons too. The popularity of this tale was greatly increased by the fact that Warren was a high-ranking Freemason and he was responsible for erasing the message. This led some to interpret the writing as a ‘Masonic message’ incorporating ritual and legend.

According to author Stephen Knight and others, there was a Masonic conspiracy behind the murders. They say there was a plot to protect the Crown from the consequences of a supposed marriage between Prince Albert Victor (later the Duke of Clarence), second-in-line to the throne, and a Roman Catholic commoner named Annie Crook. Their theory has it that the word ‘Juwes’ was the collective name for Jubelo, Jubela and Jubelum, the mythical murderers of the equally mythical Hiram Abiff, master-mason of Solomon’s Temple. Supposedly, the three men were caught and killed by having their throats cut and their bodies mutilated in a manner imitated by the killer of Annie Chapman and Catherine Eddowes. Unfortunately for this idea, the word ‘Juwes’ is not a Masonic one and the three murderers are referred to collectively in the third degree Masonic ritual as ‘ruffians’. The names Jubelo, Jubela and Jubelum were used in the late eighteenth century but were dropped during a major revision of the ritual in 1814–16. In the USA the three are still named but, as in England, they are collectively referred to as ‘ruffians’ and the word ‘Juwes’ is not known. An explanation is given by the Grand Lodge:

the three ceremonies of Craft Freemasonry are based on the Biblical story of the building of King Solomon’s Temple. They do not claim to be historical truth but are allegories to present in a dramatic form the principles a Freemason is expected to practice. In the ritual Hiram Abiff represents the principle of fidelity to a promise. He was attacked and killed by three Fellowcrafts who demanded of him the ‘secrets’ of Master which he refused to divulge.

The killing of Hiram Abiff is still central to the third degree but his body was not mutilated by his attackers as Knight and others have suggested. The mutilations of the Ripper’s victims do not parallel the symbolic physical penalties that are formally part of the obligations taken by a Freemason.

Part of Knight’s theory depends upon his belief that all the key players were Freemasons, bound by oaths to protect one another. The reality is that the only Freemasons involved in Knight’s story were the Prince of Wales, Sir Charles Warren and a man that he missed, George Akin Lusk, President of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee. (Neither did Knight notice the Lodge of Instruction in Hanbury Street.) It is also necessary to point out that Freemasons do not swear to protect one another regardless of the circumstances. The opposite is true. In the third degree ritual the candidate swears: ‘that my breast shall be the sacred repository of his secrets when entrusted to my care – murder, felony, and all other offences contrary to the laws of God and the ordinances of the realm being at all times most especially excepted’.

Warren founded the Quatuor Coronati Lodge, the first in the world devoted to Masonic history and research, and it might be assumed that he had a great knowledge of the subject. It might also be thought that he read something into the Goulston Street message which others missed and this would explain why he ordered it to be erased. However, it seems Warren did not have deep antiquarian knowledge of the Craft; at a lodge meeting he said he was only a novice in such matters. On other occasions he regularly confessed that he had not ‘as yet studied the medieval legends’ of Freemasonry, and knew ‘very little of modern Masonry’.

If there is no Masonic connection, Warren must have had another motive for rubbing out the message and it seems he feared anti-Jewish riots. He explained his actions in a letter to the Home Office on 6 November 1888:

The most pressing question at that moment was some writing on the wall in Goulston Street evidently written with the intention of inflaming the public mind against the Jews, and which Mr. Arnold with a view to prevent serious disorder proposed to obliterate, and had sent down an Inspector with a sponge for that purpose telling him to await his arrival.–

I considered it desirable that I should decide this matter myself, as it was one involving so great a responsibility whether any action was taken or not. I accordingly went down to Goulston Street at once before going to the scene of the murder: it was just getting light, the public would be in the streets in a few minutes, in a neigh-bourhood very much crowded on Sunday mornings by Jewish vendors and Christian purchasers from all parts of London. – There were several Police around the spot when I arrived, both Metropolitan and City. – The writing was on the jamb of the open archway or doorway visible to anybody in the street and could not be covered up without danger of the covering being torn off at once. – A discussion took place whether the writing could be left or covered up or otherwise or whether any portion of it could be left for an hour until it could be photographed, but after taking into consideration the excited state of the population in London generally at the time the strong feeling which had been excited against the Jews, and the fact that in a short time there would be a large concourse of the people in the streets and having before me the Report that if it was left there the house was likely to be wrecked (in which from my own observation I entirely concurred) I considered it desirable to obliterate the writing at once, having taken a copy of which I enclose a duplicate.

As we have seen, PC Long said he found the piece of apron ‘lying in the passage of the door-way … above it on the wall written in chalk “The Juews are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.”’ After a hasty search, if it can be called such, Long hurried away to the police station. All this happened in less than 15 minutes. In his report Superintendent Arnold said the writing ‘was on the wall of the entrance’ at shoulder height and could have been rubbed by people passing in and out of the building. City of London Detective Daniel Halse corroborated Long, adding that the message was on the black fascia of the wall; at the Eddowes inquest he said: ‘The writing was in the passage of the building itself, and was on the black dado of the wall.’7 Halse returned to Goulston Street and sent a message by a colleague to Inspector McWilliam to have the writing photographed. Directions were given for this to be done but the writing was rubbed out by the Metropolitan Police before it could be carried out. Halse claimed that he protested at what was being done and wished the wording kept until it could be seen by Major Smith, at this time Acting Commissioner. This series of events is one of the puzzles of the night. And where, indeed, was Major Smith? According to his own account:

The night of Saturday, September 29, found me tossing about in my bed at Cloak Lane Station, close to the river and adjoining Southwark Bridge. There was a railway goods depot in front, and a furrier’s premises behind my rooms; the lane was causewayed, heavy vans were constantly going in and out, and the sickening smell from the furrier’s skins was always present. You could not open the windows and sleep was an impossibility.

Suddenly the bell by his head rang violently and putting his ear to the tube, he was told there had been another murder. Inspector Collard at Bishopsgate police station was told at 1.55 a.m. and telegraphed headquarters immediately. Smith, according to his own account, jumped out of bed and ran into the street a couple of minutes later. Then he was in a hansom cab – designed for two, but with a 15-stone superintendent beside him and three detectives hanging on behind. They hurried to Mitre Square with the cab rolling like a ‘seventy-four’ in a gale. From there Smith went with Inspector Collard and Detective Halse to the mortuary before returning with Halse to Mitre Square. There they were told that a piece of apron had been found in Goulston Street. Later, he claimed, he went to Dorset Street where he saw bloodstained water in a street sink; he believed the murderer had washed his hands there but no indication of this survives in police reports. Even if it were the case, there were so many slaughter-houses in Whitechapel, the discovery of a bloody sink might be expected. Smith ends his report by saying that he wandered around the station houses hoping that someone might be brought in and ‘finally got to bed at 6 a.m., after a very harassing night, completely defeated’.

The astonishing feature of this account is that Smith makes no mention of going to Goulston Street where one of his own detectives was waiting and had made arrangements with Inspector McWilliam for the writing to be photo-graphed. Nor was Halse on his own – Warren himself said that when he arrived at the scene there were several police officers around, both Metropolitan and City. And it was less than ¾ mile from Mitre Square to Goulston Street – even less from Dorset Street. The writing was not rubbed out until 5.30 a.m. and Smith had at least two hours in which to be told of and view the message before its obliteration. He had already been in bed for about an hour when Warren, accompanied by Superintendent Arnold, went to the City Police headquarters to liaise with Inspector McWilliam. According to Smith, McWilliam told Warren that rubbing out the message was a ‘fatal mistake’.

A City of London Police constable guards the entrance arch to the City of London Police headquarters at 26 Old Jewry. Note the duty armband worn on the left sleeve. Sergeants wore them on the right sleeve.

Warren’s statement that ‘the house was likely to be wrecked’ by people rising up against the Jews if the message was not removed is certainly misleading. The building, still standing, is not a house but a five-storey apartment block. There is, of course, always the possibility that the wall writing was simply a piece of graffiti totally unrelated to the murders. It is likely that both Long8 and Halse had initially missed the piece of apron discarded by the murderer as he fled from Mitre Square around 1.50 a.m.

What is clear from statements made by Warren and others is that a genuine fear of disturbances, possibly developing into riots, prompted the erasing of the wall writing. If Smith is accurate in his assertion that Inspector McWilliam told Warren that by the rubbing out he had made a ‘fatal mistake’ then there may have come the belated realisation that by not photographing the message he had given the press yet another stick with which to beat him. Nor would he have been wrong. The news that Warren had destroyed what seemed to be the first genuine clue left by the murderer was eagerly pounced upon and he was seriously criticised for what he had done. The Pall Mall Gazette, malicious as ever, hoped that he would be censured by the coroner.

The City Police fared little better than the Met in the press. Superintendent Foster told a Star reporter on the morning of 2 October that he believed they were dealing with a man who was far too clever to go about boasting of what he was going to do. Every drunken man was likely to seek temporary notoriety by proclaiming himself the Whitechapel murderer, he said. Many reports of men claiming to be the killer were taken up by the detectives immediately, not so much because they expected to get a clue out of them but rather because it might be unsafe to ‘neglect anything of that character’. When the Star’s man made his rounds of the police stations that morning ‘the detectives had come to a standstill’. A man with a strong Birmingham accent was arrested in the City late on Monday 1 October and was detained at the police office in Old Jewry. He had been seen ‘behaving in a mysterious manner’ in the streets and when he was stopped by the police he refused to give an account of himself. He gave ‘unintelligent answers’ to their questions and as a result was thought to be insane. He was examined by two doctors. At 1.45 a.m. on Tuesday 2nd the attention of police on duty near Holborn Circus was attracted by screams and cries of ‘Murder’. They found a woman who was apparently in great distress and arrested a man whom she said had tried to induce her to go up a neighbouring court. He had threatened to kill her if she did not comply with his demands. The man was a portly German with a heavy moustache who gave his name as Augustus Nochild, a tailor, of 86 Christian Street, Whitechapel. Sergeant Parry took him to Snow Hill police station. No knife was found on him.

After the sensation of two East End murders in one night, the newspapers were full of reports on the events in Whitechapel and its environs. Needless to say there were further stories of suspects. The Star boasted the ‘largest circulation of any evening paper in the kingdom’ and on Monday 1 October 1888 its coverage of the murders was extensive. Of the 24 columns in its 4 pages, more than 8 were devoted to the murders. The Star was critical of the authorities and not short of suggestions about what should be done. Needless to say, the newspaper considered many theories and suggested its own. The journalists were quick to dismiss the theory recently put forward by coroner Wynne Baxter:

And, first, let us examine the facts, and the light they throw on any previous theories. To begin with it is clear that the BURKE and HARE theory is all but destroyed. There is no suggestion of surgical neatness, or of the removal of any organ, about the Mitre-square murder [sic – in fact, the uterus and left kidney had been taken]. It is a ghastly butchery – done with insane ruthlessness and violence. The gang theory is also weakened, and the story of a man who is said to have seen the Berner-street tragedy, and declares that one man butchered and another man watched, is, we think, a priori incredible. The theory of madness is on the other hand enormously strengthened. Crafty blood-thirst is written on every line of Sunday morning’s doings. The rapid walk from Berner-street to Aldgate, to find a fresh victim, the reckless daring of the deed – in itself the most dangerous and cunning of all the murderer’s resources – these all point to some epileptic outbreak of homicidal mania. The immediate motive need not trouble us now, except so far as it suggests the invariable choice of the poor street-wanderers of the East-end. It may be, as Dr. SAVAGE supposes, a plan of fiendish revenge for fancied wrongs, or the deed of some modern Thug or Sicarius, with a confused idea of putting down vice by picking off unfortunates in detail. A slaughterer or butcher who has been in a lunatic asylum, a mad medical student with a bad history behind him or a tendency to religious mania – these are obviously classes on which the detective sense which all of us possess in some measure should be kept. Finally, there is the off-chance – too horrible almost to contemplate – that we have a social experimentalist abroad determined to make the classes see and feel how the masses live.

This rather insightful article contained many ideas that have been adopted by modern theorists. It considered possible methods of the murderer, including that he had some rough knowledge of anatomy, that probably only his hands would be smeared by blood, and that after doing the deed he would don gloves. It was thought that he must have done so to ensure Eddowes did not see the blood, if, indeed, the two deeds were the work of one hand. (This is an interesting reference to the fact that there may have been two murderers.) As a further precaution, the Star said, he might have put an overcoat on after the deed. As he apparently stopped nowhere to wash his hands, he probably did not live in a lodging house or hotel, but in a private house where he had ‘special facilities – perhaps the chemicals and a wash-hand stand communicating directly with a pipe – for getting rid of bloody hands and clothes’. The journalist thought that the murderer must be inoffensive, probably respectable in manner and appearance, or else how could woman after woman have been decoyed by him? Two theories had been suggested to the Star: that he wore women’s clothes or that he was a policeman. These ideas appear repeatedly in letters to the police from the public.

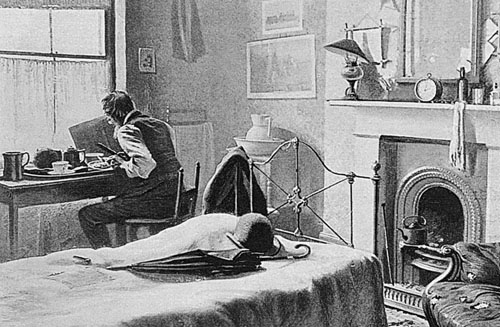

Many Ripper theories are built on the idea of the Ripper being a lodger living in the privacy of his own rented room. Here is an illustration of a Victorian lodger in his bed-sitting room in the East End.

A very significant development – from press, public and police points of view – occurred at this time. The ‘Jack the Ripper’ correspondence began with the publication of the infamous ‘Dear Boss’ letter. This letter, written in red ink, purported to have come from the murderer and was addressed to ‘The Boss’ at the Central News Agency in the City. It was dated 25 September 1888 and posted on the 27th. The agency forwarded the letter to the police on Saturday 29th, the eve of the ‘double event’ and on the Monday following it was made public. It read:

25 Sept: 1888.

Dear Boss

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha. ha. The next job I do I shall clip the lady’s ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldn’t you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work then give it out straight. My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good luck.

Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Dont mind me giving the trade name

[Then at right angles to above:]

wasnt good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it.

No luck yet. They say I’m a doctor now ha ha

This letter was forwarded to the police by Thomas John Bulling, a 42-year-old Central News reporter. The sensation created by the letter, coupled with the sale of the story to the newspapers, generated added income for the agency, a fact that was commented on at the time.

The ‘Dear Boss’ letter was quickly followed by the equally notorious ‘saucy Jacky’ postcard sent to the same agency on 1 October:

I wasn’t codding dear old Boss when I gave you the tip. youll hear about saucy Jackys work tomorrow double event this time number one squealed a bit couldn’t finish straight off. had not time to get ears for police thanks for keeping last letter back till I got to work again

Jack the Ripper

These two items of correspondence are the origin of the name ‘Jack the Ripper’ and this incredibly apt and sensational moniker for the unknown killer was immediately universally adopted. It has never been out of use since. If it was the work of the pressmen, which seems more than likely, it was a master stroke. According to Chief Inspector John George Littlechild, head of the Special Branch, senior officers at Scotland Yard believed Tom Bulling, and possibly his manager, Mr Moore, penned the letter.9 Indeed, seasoned journalist George R. Sims wrote in his ‘Mustard and Cress’ columns in the Referee of 7 October:

The fact that the self-postcard-proclaimed assassin sent his imitation blood-besmeared communication to the Central News people opens up a wide field for theory. How many among you, my dear readers, would have hit upon the idea of ‘the Central News’ as a receptacle for your confidence? You might have sent your joke to the Telegraph, the Times, any morning or any evening paper, but I will lay long odds that it would never have occurred to you to communicate with a Press agency which serves the entire Press? It is an idea which might occur to a Press man perhaps; and even then it would probably only occur to someone connected with the editorial department of a newspaper, someone who knew what the Central News was, and the place it filled in the business of news supply. This proceeding on Jack’s part betrays an inner knowledge of the newspaper world which is certainly surprising. Everything therefore points to the fact that the jokist is professionally connected with the Press. And if he is telling the truth and not fooling us, then we are brought face to face with the fact that the Whitechapel murders have been committed by a practical journalist – perhaps by a real live editor! Which is absurd, and at that I think I will leave it.

The publication of the letter and the postcard heralded a flood of similar correspondence that was to plague the police investigation and further muddy the waters. There is no doubt that Warren himself viewed the ‘Dear Boss’ correspondence as a hoax. Writing to Lushington at the Home Office on 10 October, he said: ‘At present I think the whole thing is a hoax but of course we are bound to try & ascertain the writer in any case.’10

The Star of Tuesday 2 October 1888 contained further lengthy coverage of the murders, including extracts from letters received concerning the case. ‘A Laborer’ suggested that the perpetrator of the murders might be a woman, a Kate Webster11 who had gained anatomical knowledge while learning midwifery. Fred W. Ley suggested that the murderer was a religious fanatic. Mr T. Barry thought that the man must be one who, ‘having been ruined by dissipation, was having his revenge’. ‘A Reader’ thought the murderer would be found ‘among a class well known to the unfortunates themselves’ because he escaped so easily. C.J. Solomons of Hanbury Street, Spitalfields, had come to the conclusion that the murders could not have been committed by any person living in a common lodging house because signs of blood would certainly have been noticed on him: it must be someone who had a room where he could go unnoticed at any time and make a change of clothing. ‘Justice’ thought the perpetrator might be a fanatical member of the Society for the Suppression of Prostitution or of a vigilance committee, who was murdering to frighten prostitutes from the streets.