THE police response to the double murder on 30 September 1888 was swift. Within hours Warren had 10,000 leaflets printed asking for information about the killings between 31 August and 30 September. Clearly he did not consider the Smith and Tabram murders to be part of the pattern that was now developing. Next day, even before Eddowes had been identified, the lord mayor, on the recommendation of the City Police commissioner, offered a reward of £500 for information leading to the arrest of the unknown killer.

Just how the City Police investigation was shaping up did not become clear to the Home Office until it asked for a report from the City Police commissioner almost four weeks later. The reason for this lack of information was the unusual nature of the City’s relationship with the Home Office: the cost of the force was borne entirely by the Corporation of the City of London. Because there was no government funding for the City Police, the Home Office had no say in how the force was run nor any authority over either it or its commissioner.

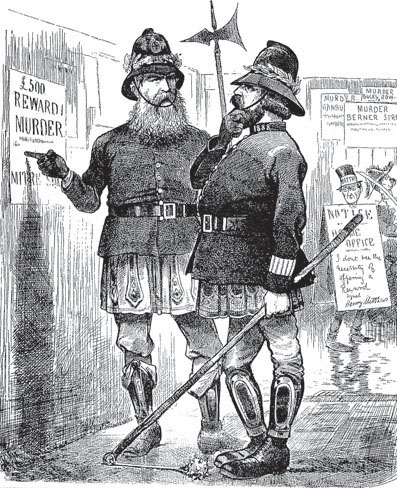

‘Gog and Magog on their Mettle.’ ‘I say, matey, we’ve a share in this murder business now, and we’ll have to act in a different way to those Metropolitan fellows’, says one City of London Police constable to another in this Funny Folks cartoon of 6 October 1888. The Eddowes murder had brought the City Police into the investigation.

Two City of London Police constables check an old City graveyard at night. Similar scenes took place during the Ripper scare.

A lengthy report from Detective Inspector McWilliam1 was received on 29 October giving details of the investigation to date and the coroner’s inquest. He also told the home secretary that he had sent officers to all the lunatic asylums in London seeking details of people recently admitted or discharged; because it was the opinion of many that the crimes were too revolting to have been committed by a sane person. The Home Office minute sheet accompanying this report2 is particularly interesting as William Byrne, a Home Office clerk and a barrister, noted on it: ‘This report tells very little’ and: ‘The printed report of the Inquest contains much more information than this. They evidently want to tell us nothing. ?Shall we ask them.’ This is a little unfair as the City Police were under no obligation, unlike the Metropolitan Police, to report to the Home Office. Indeed, McWilliam’s report is quite detailed and useful. (It is certainly fortunate that it was submitted in view of the later loss of the bulk of the City Police material.)

A detective, Sergeant Robert Sagar, was one of the liaison officers deputed to represent the City in meetings with senior detectives in nightly conferences with the Metropolitan force at Leman Street police station. A report from Chief Inspector Swanson explained that the investigations conducted by the two forces had merged into one another, ‘each force cordially communicating with the other daily the nature and subject of their enquiries.’

The Whitehall Mystery – the discovery of a female torso in the basement of New Scotland Yard on 2 October 1888. The building on the Victoria Embankment was then under construction. A mystery indeed, but not another Ripper murder. (Penny Illustrated Paper)

So far the murders had been confined to one small area of the East End and City but on the afternoon of Tuesday 2 October a headless and limbless female torso was found in the basement area of the new Norman Shaw building under construction on the Victoria Embankment. (It was to be the new Metropolitan Police headquarters – New Scotland Yard – to replace the old buildings at Whitehall Place.) The body’s right arm and hand had been found in mid-September on the foreshore of the Thames. This case became known as the ‘Whitehall Mystery’. Inevitably, the press became alarmist at the news, trying to forge links with the Whitechapel murders by suggesting that the killer had moved further west and was extending his boundaries, making no woman safe in London. There were even attempts to claim that the torso had been put into the basement as a way of taunting Warren and Matthews for their lack of success in catching the culprit. Some newspapers firmed up the connection with Whitechapel by claiming this unknown person was the Ripper’s seventh victim. There was more embarrassment for the police when two amateur detectives using a sniffer dog dug up a human leg, severed just above the knee, in the cellar where the torso had been found. Constant rehashing of the Whitehall Mystery kept the newspapers busy until the story was knocked off the front page by more sensational news.

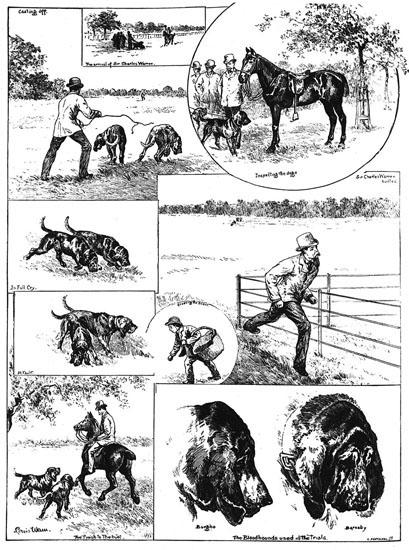

The bloodhounds used in trials – Burgho and Barnaby. Illustration by the famous animal artist Louis Wain.

The introduction of dogs into the hunt for the Ripper resulted in press cartoons of dogs as policemen, like this example from the Penny Illustrated Paper.

Suggestions had come from several sources that bloodhounds should be deployed to capture the killer and in the early hours of 9 October Warren witnessed a private trial of the dogs in Hyde Park. The bloodhounds belonged to Edwin Brough, who had been breeding the animals for several years. At the police’s request he brought two bloodhounds, one named Champion Barnaby and the other a black-and-tan called Burgho, from Scarborough to London. They were tested over two days in Regent’s Park and Hyde Park, with Warren himself acting as the hunted man on two occasions. The cost of the bloodhounds became something of a problem and Warren could give no definite assurance that the police would purchase the dogs. The intention was to take them to the site of the next murder, should it happen. Eventually they were returned to Scarborough but not before the newspapers had with great glee reported a totally fictitious story that they had been lost in a fog!

The double murder of 30 September prompted local demands for a further strengthening of police numbers in Whitechapel. Warren replied by return to the clerk of the Board of Works, which had passed a resolution to this effect, that he could not do more to guard against such murders ‘so long as the victims actually, but unwittingly, connive their own destruction’. London, he went on, was the safest city in the world in which to live but increasing police strength would not help prevent this particular type of murder when the unfortunate victims appeared to take the killer to some isolated spot where they could be slaughtered without a sound being heard. He asked the board to try to dissuade women from going into these dark and lonely places with anyone, be they acquaintance or stranger. He pointed out the poor street lighting and resulting darkness, which did not help. Extra police had already been drafted into the area but only at the expense of other divisions – and normal police work still had to be done. He concluded by correcting a number of misconceptions which had arisen in the public mind and asked the board to dismiss ‘as utterly fallacious, the numerous anonymous statements as to recent changes to have been made in the police force, of a character not conducive to efficiency’. There was no truth in the statement, which he had seen repeated many times, that constables were constantly being moved from district to district and therefore had no local knowledge. The system in use had existed for the last twenty years and constables were only moved on promotion or for some other reason. As far as the detectives were concerned, he had recently made arrangements which further reduced the necessity of transferring officers from one district to another. He ended by saying that one member of the board had said that a revision of police arrangements was necessary: perhaps the clerk would let Warren know what these necessary revisions were and he would give them every consideration.

A member of Parliament suggested to the home secretary that a cordon should be placed around Whitechapel and compulsory house-to-house searches made. When this idea was forwarded to Warren he threw it back, almost certainly tongue in cheek, saying that he was quite prepared to take the responsibility of adopting such drastic or arbitrary measures which would capture the murderer, ‘however illegal they may be’, but since the Home Secretary could not order him to do an illegal act, the responsibility must remain his. In the circumstances he wanted a government guarantee that there would be an indemnity for such an action: ‘I have been accustomed to work under such in circumstances in what were nearly Civil wars at the [missing] & then the Government passed Acts of indemnity for those who have gone beyond the law.’ He then went on to rub Home Secretary Matthews’ nose in the suggestion by showing just how ludicrous it was. Of course, he said, in performing such an illegal act, Warren would be criticised if the murderer were not found. Such an illegal act might bond the Social Democrats together and he would then be accused of causing a riot. Houses ‘could not be searched illegally without violent resistance & blood shed and the certainty of one or more Police Officers being killed’. There was the added possibility of a police officer being tried and hanged if a death resulted from an illegal search. Matthews sent a swift reply by return of post: the MP’s suggestion was ‘too sweeping’. In a postscript he pointedly asked if Anderson, absent now for a month and just returned from Paris, was well enough to resume his duties.

Warren had no intention of antagonising the people of Whitechapel. He needed their help and successfully arranged and carried out house-to-house searches in suspect areas with their cooperation. Two weeks later, after this exchange of letters with Matthews, Warren was able, through The Times, to thank publicly the people of the East End for the way they had helped the police with their inquiries. He felt that some acknowledgement was due ‘on all sides for the cordial cooperation of the inhabitants’. He similarly acknowledged the immense volume of correspondence he had received and asked the writers to accept this statement in lieu of individual replies.

The Pall Mall Gazette, hostile as ever, now mounted a series of attacks in articles called ‘The Police and Criminals of London’ and with subtitles like ‘The Headless C.I.D.’ and ‘Why Detectives Don’t Detect’. They were very much pro-Monro and anti-Warren. Their tone was alarmist and they warned that unless a change was made (i.e. Warren and/or Matthews removed) there would be not only ‘a widespread panic as to the growing insecurity of life and property in the metropolis’ but a police strike resulting from disaffection over pay and pensions. ‘All kinds of explanations, excuses, apologies had been made for the failure of the police to catch the murderer’ except the obvious one that they had failed because the CID no longer had a head. In fact, Anderson had returned two days before the article appeared. Unaware of this, the reporter continued that Monro’s position after four years had become intolerable. But Dr Anderson, his successor, a millenarian and writer of books, was only there in spirit: ‘You may seek for him in Scotland-yard, you may look for him in Whitehall-place, but you will not find him, for he is not there. Dr. Anderson, with all the arduous duties of his office still to learn, is preparing himself for his apprenticeship by taking a pleasant holiday in Switzerland!’

Police mocked in this Punch cartoon of 22 September 1888.

The article ended with a not unexpected attack on Warren who was blamed for decapitating the CID and making Scotland Yard a laughing stock. The police themselves were accused of destroying clues, in particular the grape stalks which had been recovered by the Vigilance Committee’s private detectives and which, whether the newspaper knew it or not, were a part of Packer’s fictional and discredited account of the Stride murder. More laughable still, the writer complained of Warren’s doubling of police patrols which meant the doubling of the sound of policemen’s footsteps to warn the murderer of their approach! There was nothing but praise for Monro who had resigned because ‘Sir Charles Warren would interfere, over-rule and dictate in matters which had heretofore been regarded as the legitimate province of the Assistant Commissioner’ and who now had ‘to face the situation which his overbearing and tactless interference had created’.

Warren replied to these and other charges in a statement to The Times on 10 October. The piece was headed ‘Sir Charles Warren and the Detective Force’. Warren explained the basic height regulation, age limits, rules governing pensions and applications to the CID. He said that as a general rule it had been ascertained by the Criminal Investigation Department that candidates who had applied to be appointed directly to the CID without serving first in the uniform branch had not possessed any special qualities which would justify their acceptance. The tone of the statement was reasonable but it was not enough to stop the criticism. Newspaper coverage of the murders and the determination of some, including the Gazette, to exact revenge for the ‘Bloody Sunday’ riots had made of Warren a national hate figure. In Sheffield, where he had stood just a few years before as a Liberal candidate, the mention of his name at a Liberal meeting was received ‘with hisses and cries of disapprobation’. Asquith was the speaker and reflected that ‘he could not help thinking there were moments when the Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police would look back with vain but unavailing regret to the time when, as one of the Radical candidates for Sheffield, he was the stalwart and outspoken champion of popular rights’.

Despite the £1,200 now being offered by the City, the Financial News and private individuals, the Home Office still refused to offer a reward for information or capture of the murderer. Until 1884 it had been policy to offer rewards from £200 to £2,000 – the highest ever was £10,000 for the Phoenix Park murders. The system of rewards was abandoned in early 1884 when a conspiracy was formed to cause an explosion at the German Embassy before planting papers on an innocent man to accuse him of the crime and obtain the expected reward. Such ‘blood money conspiracies’ had been a common feature of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century law enforcement.

Warren was initially against offering a reward – in common with others he did not think that it would achieve much, except that the gesture might be a popular one. After thinking further he changed his mind, especially if in addition to the reward, a free pardon was offered to any accomplice who was not the murderer. Anderson, after taking soundings from the divisions and Williamson, agreed with him. Warren looked ‘upon this series of murders as unique in the history of our country’ and in a totally different category to anything that had gone before.

The suggestion of a pardon had been made by George Lusk of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee in a letter to the home secretary. Warren had the idea at about the same time, his reasoning being that if the murderer was sane, with periodic fits of insanity, relatives and neighbours may have unwittingly slipped into the position of becoming accomplices with no way of escape from their predicament except by the offer of a pardon. Or, if the murders were being committed by a gang with only one person doing the killing, the free pardon might tempt an informer. Coincidentally, Warren was at this time in touch with someone who claimed to be such an accomplice and was asking for a free pardon; communication between the two men was through an advertisement in a journal. Warren thought the whole thing might be a hoax but felt it worth following up.

Matthews, however, was privately consulting with Monro who was against rewards. So, too, Matthews informed Warren, was the commissioner’s predecessor, Colonel Henderson. Warren was having none of it and wrote back that while the home secretary had been given one set of views, he had a memoranda, which he enclosed, not only from both men but from Williamson too in favour of rewards. It may have been about this time that Warren discovered control of the CID had effectively moved from Scotland Yard to the Home Office. Every morning protracted conferences were held there between Monro, Anderson (Monro’s protégé), Williamson and the principal detectives, including Abberline. Only information of the ‘scantiest character’ was passed back to the commissioner. All of this could only be done with the backing of the home secretary. Matthews was subsequently to admit that throughout this period he benefited from Monro’s advice and discussed with him the organisation of the detective department. As Anderson was to say, the Home Office acted more like a blister than a plaster.

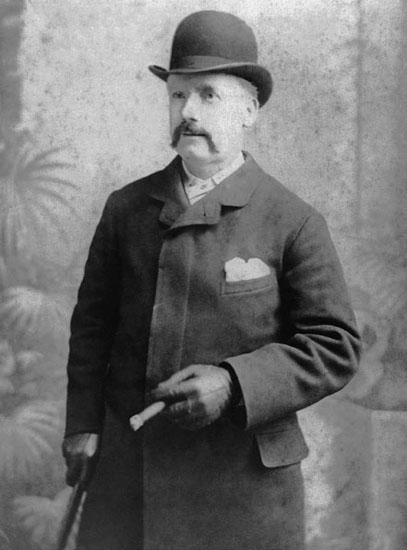

George Akin Lusk, c. 1885. (Courtesy of the late Leonard Archer)