Chapter 1

Better, Not Perfect

In April 2018, I was scheduled to be interviewed at an Effective Altruism conference at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, about three miles from my home in Cambridge, Massachusetts.1 Unable to attend the whole conference, I arrived about an hour before my interview. I entered a large room filled with a few hundred attendees, most of them under the age of thirty, and had the somewhat random, and definitely lucky, opportunity of hearing the speaker before me, Bruce Friedrich. I had not met Bruce before, but his talk rocked my world—personally and academically. A lawyer and the CEO of the Good Food Institute (gfi.org), Bruce introduced me to a new way of thinking about reducing animal suffering. He noted in his talk that the growth of vegetarianism—a commitment to eating no meat or fish—has been very limited. One clear reason for this is that preaching to your friends about the virtues of vegetarianism is not an effective way to change their behavior or maintain your relationships with them. So, what can a vegetarian do to help others also leverage the benefits of lower consumption of animals and improve society (by improving the environment and human health, making our food production more efficient so that we can feed the world’s hungry, and reducing the risks of a growing antibiotic crisis)?

Bruce answered this question by introducing a world of entrepreneurs, investors (some amazingly wealthy), and scientists who are working with the Good Food Institute to create and encourage the consumption of new “meats” that taste very similar to meat, without requiring the pain, suffering, or death of any animals. These alternative meats included new plant-based products already on the market (such as Beyond Meat and the Impossible Burger), as well as “cultivated” (also called “clean” or “cell-based”) meat that will be grown from the cells of real animals in a lab and produced without the need for more animal deaths. Bruce argued that producing meat alternatives that are tasty, affordable, and readily available in grocery stores and restaurants is a much more fruitful means of reducing animal suffering than preaching about the negative effects of meat consumption. It’s a profitable enterprise, too: within a year of Bruce’s talk, at its initial public offering, the relatively new company Beyond Meat was worth $3.77 billion. Months later, the company’s value soared billions higher.

Many management scholars define leadership as the ability to change the hearts and minds of their followers. But note that Bruce’s strategy had little to do with changing people’s values and everything to do with motivating them to change their behavior, with little or no sacrifice required. This is just one example of how we can adjust our own behavior—and encourage others to do the same—in ways that will create more net good. We’ll explore many more of them in this book.

THE SPACE BETWEEN

I have spent my career as a business school professor. Business schools aim to offer practical research and instruction on how to do things better. I often offer my students prescriptions for how to do better, from making better decisions to negotiating more effectively to being better more broadly. By contrast, ethicists tend to either be philosophers who highlight how they think people should behave, or behavioral scientists who describe how people actually behave. We will aim to carve out a space between the philosophical and behavioral science approaches where we can prescribe action to be better. First, we need a clear understanding of the foundations on which we are building.

Philosophy’s Normative Approach

Scholars from a range of disciplines have written about ethical decision making, but by far the most dominant influence has come from philosophers. For many centuries, philosophers have debated what constitutes moral action, offering alternative normative theories of what people should do. These normative theories generally differ on whether they argue for the maximization of aggregate good (utilitarianism), the protection of human rights and basic autonomy (deontologists), or the protection of individual freedom (libertarianism). More broadly, moral philosophies differ in the trade-offs they make between creating value versus respecting people’s rights and freedoms. However, they share an orientation toward recommending norms of behavior—a “should” focus. That is, philosophical theories tend to have very clear standards for what constitutes moral behavior. I am confident that I fail to achieve the standards of ethical behavior for most moral philosophies (particularly utilitarianism) on a regular basis and that if I attempted to be purely ethical from a philosophical perspective, I would still fail.

Psychology’s Descriptive Approach

In recent decades, particularly after the collapse of Enron at the beginning of the millennium, behavioral scientists entered the ethical arena to create the field of behavioral ethics, which documents how people behave—that is, it offers descriptive accounts of what we actually do.2 For example, psychologists have documented how we engage in unethical acts based on our self-interest, without being aware that we’re doing so. People think they contribute more than they actually do, and see their organization and those close to them as more worthy than reality dictates. More broadly, behavioral ethics identifies how our surroundings and our psychological processes cause us to engage in ethically questionable behavior that is inconsistent with our own values and preferences. The focus on descriptive research has not been on the truly bad guys that we read about in the newspaper (such as Madoff, Skilling, or Epstein), but on research evidence showing that most good people do some bad things on a pretty regular basis.3

Better: Toward a Prescriptive Approach

We’ll depart from both philosophy and psychology to chart a course that is prescriptive. We can do better than the real-world, intuition-based behavior observed and described by behavioral scientists, without requiring ourselves or others to achieve the unreasonably high standards demanded by utilitarian philosophers. We will go beyond diagnosing what is ethical from a philosophical perspective and where we go wrong from a psychological perspective to finding ways to be more ethical and do more good, given our own preferences. Rather than focusing on what a purely ethical decision would be, we can change our day-to-day decisions and behavior to ensure they add up to a more rewarding life. As we move toward being better, we’ll lean on both philosophy and psychology for insights. A carefully orchestrated mix of the two yields a down-to-earth, practical approach to help us do more good with our limited time on this planet, while offering insight into how to be more satisfied with our life’s accomplishments in the process. Philosophy will provide us with a goal state; psychology will help us understand why we remain so far from it. By navigating the space between, we can each be better in the world we actually inhabit.

ROAD MAPS FROM OTHER FIELDS

Using normative and descriptive accounts to generate a new prescriptive approach aimed at improving decisions and behavior is novel in the realm of ethics, but we’ve seen this evolution play out in other fields, namely negotiation and decision making.

Better Negotiations

For decades, research and theory in the field of negotiation was divided into two parts: normative (how people should behave) and descriptive (how people actually behave). Game theorists from the world of economics offered a normative account of how humans should behave in a world where all parties were completely rational and had the ability to anticipate full rationality in others. In contrast, behavioral scientists offered descriptive accounts of how people actually behave in real life. These two worlds had little interaction. Then Harvard professor Howard Raiffa came along with a brilliant (but terribly titled) concept that merged the two: an asymmetrically prescriptive/descriptive approach to negotiation.4 Raiffa’s core insight was to offer the best advice possible to negotiators, without assuming that their counterparts would act completely rationally. Stanford professor Margaret Neale and I, along with a cohort of excellent colleagues, went on to augment Raiffa’s prescriptions by describing how negotiators who are trying to behave more rationally can better anticipate the behavior of the other less-than-fully-rational parties.5 By adopting the goal of helping negotiators make the very best possible decisions, but accepting more accurate descriptions of how people behave, Raiffa, Neale, myself, and our colleagues were able to pave a useful path that has changed how negotiation is taught at universities and practiced the world over.

Better Decisions

A similar breakthrough occurred in the field of decision making. Until the start of the new millennium, economists studying decision making offered a normative account of how rational actors should behave, while the emerging area of behavioral decision research described people’s actual behavior. Implicit in the work of behavioral decision researchers was the assumption that if we can figure out what people do wrong and tell them, we can “debias” their judgment and prompt them to make better decisions. Unfortunately, this assumption turned out to be wrong; research has shown time and again that we do not know how to debias human intuition.6 For example, no matter how many times people are shown the tendency to be overconfident, they continue to make overconfident choices.7

Luckily, we have managed to develop approaches that help people make better decisions despite their biases. To take one example, the distinction between System 1 and System 2 cognitive functioning, beautifully illuminated in Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow, presents a useful distinction between the two main modes of human decision making.8 System 1 refers to our intuitive system, which is typically fast, automatic, effortless, implicit, and emotional. We make most decisions in life using System 1 thinking—which brand of bread to buy at the supermarket, when to hit the brakes while driving, what to say to someone we’ve just met. In contrast, System 2 refers to reasoning that is slower, conscious, effortful, explicit, and logical, such as when we think about costs and benefits, use a formula, or talk to some smart friends. Lots of evidence supports the conclusion that System 2, on average, leads to wiser and more moral ethical decisions than System 1. While System 2 doesn’t guarantee wise decisions, showing people the benefits of moving from System 1 to System 2 when making important decisions, and encouraging them to do so, moves us in the direction of better, more ethical decisions.9

Another prescriptive approach to decision making came from Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s influential 2008 book, Nudge.10 While we do not know how to fix people’s intuition, Thaler and Sunstein argued that we can redesign the decision-making environment so that wiser decisions will result by anticipating when gut instincts might cause a problem—an intervention strategy known as choice architecture. For example, to address the problem of people undersaving for retirement, many employers now enroll employees automatically in 401(k) programs and allow them to opt out of the plan. Changing the decision-making default from requiring people to enroll to automatic enrollment has been shown to dramatically improve savings rates.

These fruitful developments in the fields of negotiation and decision making offer a road map, borrowing the idea of identifying a useful goal from the normative tool kit (such as making more rational decisions), and combining it with descriptive research that clarifies the limits to optimal behavior. This prescriptive perspective has the potential to transform the way we think about what’s right, just, and moral, which will lead us to be better.

A NORTH STAR FOR ETHICS

Our journey seeks to identify what better decisions would look like and chart a path to lead us in that direction. Much of moral philosophy is built on arguments that stipulate what would constitute the most moral behavior in various ethical dilemmas. Through the use of these hypotheticals, philosophers stake out general rules that they believe people should follow when making decisions that have an ethical component.

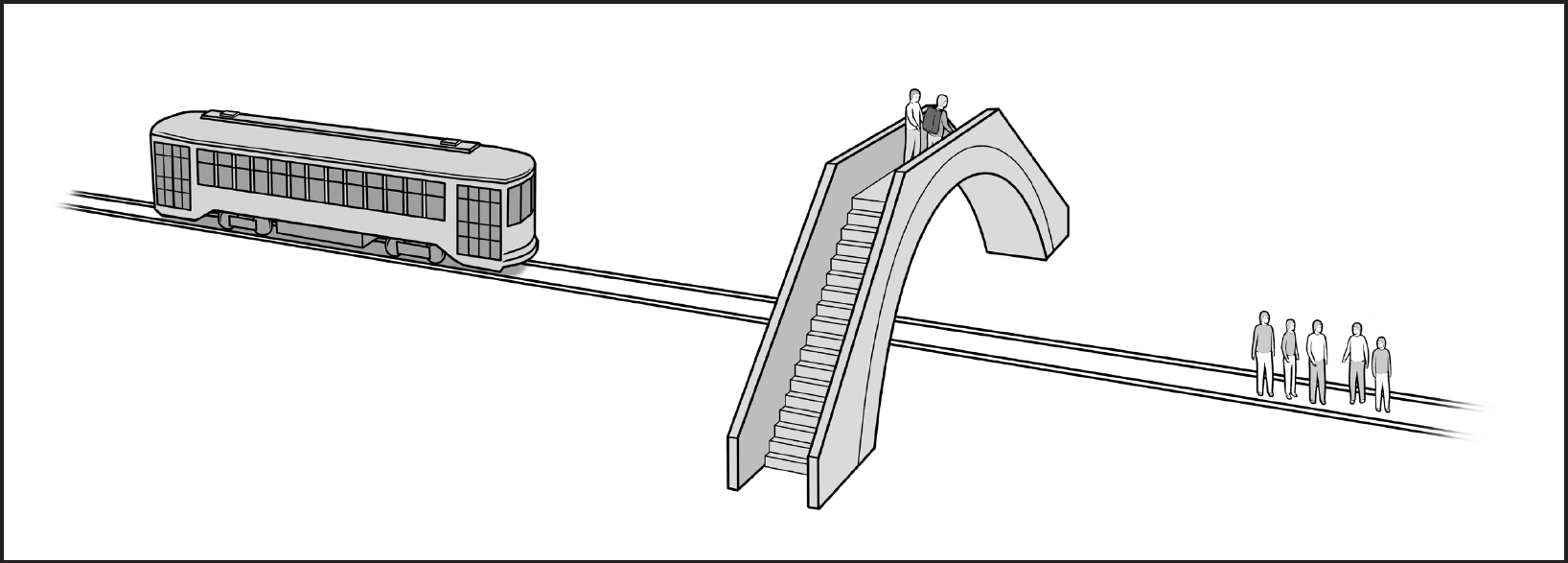

The most commonly used dilemma to highlight different views of moral behavior is known as the “trolley problem.” In the classic form of the problem, you’re asked to imagine that you are watching a runaway trolley that is bounding down a track. If you fail to intervene, the trolley will kill five people. You have the power to save these people by hitting a switch that will turn the trolley onto a side track, where it will run over and kill one workman instead. Setting aside potential legal concerns, would it be moral for you to turn the trolley by hitting the switch?11

THE TROLLEY PROBLEM

© 2019 Robert C. Shonk

Most people say yes, since the death of five people is obviously worse than the death of one person.12 In this problem, the popular choice corresponds to utilitarian logic. Utilitarianism, a philosophy rooted in work of scholars such as Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, Henry Sidgwick, Peter Singer, and Joshua Greene, argues that moral action should be based on what will maximize utility in the world. This translates into what will create the most value across all sentient beings. Of course, it is very difficult to assess which action will maximize utility across people. But for utilitarians, having this goal in mind provides clarity in lots of decisions—including the trolley problem.

For now, we use utilitarianism as a clear touchstone to help us navigate new terrain. Interestingly, many of us already endorse many of the basic moral constructs of utilitarianism:

- Creating as much value as possible across all sentient beings

- Behaving efficiently in the pursuit of the good that we can create

- Making moral decisions independent of our own wealth or status in society

- Valuing the interests of all equally

Most of my advice will hold up to criticisms of utilitarianism and be relevant even to readers who reject certain aspects of utilitarianism.

For practical purposes, maximizing aggregate value creation across all sentient beings will be the North Star of ethical behavior that we aim for in this book. Yet our behavior is not even close to alignment with these goals. Turning back to psychology, Herbert Simon noted that we have “bounded rationality.”13 That is, while we try to be rational, we face cognitive limitations to our ability to get there. Similarly, we are bounded in our ability to maximize utility in the world, as systematic cognitive barriers keep us from behaving in a more utilitarian fashion. In the chapters to come, we’ll explore those barriers and ways to get around them. Some of them are the same as those that keep us from being more rational, and greater self-awareness seeds change. Others require interventions to guard against our ethical blind spots. Either way, if you can do more good at no cost to yourself, it should be easy to move in that direction.

CLEARING SOME HURDLES

Before moving forward with utilitarianism as a North Star, it is useful to consider some of the baggage that comes along with this perspective. First, although many people agree with most, if not all, of the core components of utilitarianism, the term “utilitarianism” often angers people. Utilitarianism is hindered by a terrible name: the word suggests a singular focus on efficiency, selfishness, or even a disdain for humanism—all of which are entirely inconsistent with the intent of the creators. Clearly, Bentham and Mill didn’t have a very good marketing department. More recently, Josh Greene has advocated for replacing the term “utilitarianism” with “deep pragmatism.” “When your date says, ‘I’m a utilitarian,’ it’s time to ask for the check,” he writes in his book Moral Tribes. “But, a ‘deep pragmatist’ you can take home for the night and, later, to meet the parents.”14

Second, many people ask: Is striving for the greatest good even the right goal? Holding all else equal, virtually all of us want to do more good in the world. But all else isn’t equal, and the rights, freedom, and autonomy of other people matter to many, as a companion problem to the trolley problem illustrates.

In the footbridge dilemma, the runaway trolley is once again headed down the track and, if ignored, will kill five people. This time, however, you are standing on a bridge above the tracks next to a railway worker who is wearing a large backpack. You can save the five people by pushing the man (and his heavy backpack) off the bridge and onto the tracks below. He will die, but his body will serve as a trolley stopper to save the five. You cannot save the people yourself because you lack the trolley-stopping heavy backpack. Would it be moral for you to save the five people by pushing this stranger to his death?15

THE FOOTBRIDGE DILEMMA

© 2019 Robert C. Shonk

Most people argue against pushing the man, although the same five-for-one deal is being offered as in the trolley problem. The footbridge dilemma invokes a very different form of morality. When asked why they wouldn’t push the man, people tend to say things like, “That would be murder!” “The ends don’t justify the means!” or “People have rights!”16 These are common arguments of deontological philosophers. Thanks to the amazing work of Joshua Greene and his colleagues, we know that our divergent answers to these two problems reflect competing responses in different parts of the brain.17 In the footbridge problem, when we think about the rights of the potential “victim” being pushed to save five other people, our emotional response activates the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. But when some people override this emotional impulse and create value by saving the most lives possible, the decision is driven by controlled cognitive processes in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.18 The evidence strongly suggests that the act of pushing the person off the bridge invokes an emotional process that is missing in most of us when we confront the trolley dilemma. Even so, some people make consistent decisions across the two problems: they say they would hit the switch in the first problem and push the man in the second.

But there’s one more problem in this series, and this one pushes even avowed utilitarians over the edge, so to speak. It’s the surgeon problem, adapted from the late British philosopher Philippa Foot:19

Five patients are being cared for at a hospital and are expected to die soon. A sixth man is undergoing a routine checkup at the same hospital. A transplant surgeon in residence finds that the only means of saving the five ailing patients would be to slay the sixth person and transplant his healthy organs into the five. Would it be morally right to do so?

Not surprisingly, most people are appalled by this question and quickly reject this five-for-one deal. Just to be clear, I too am staunchly opposed. Why are so many of us willing to hit the switch in the original trolley problem, yet almost no one is in favor of harvesting the five organs from the healthy person in the surgeon problem? Because even strongly leaning utilitarians bring real-world baggage to their decision making. Namely, we realize that society’s many rights and rules create second-order value. That is, if an innocent person can be dragged off the street to save five people dying in a hospital, society will break down, and there will be fewer opportunities to create pleasure and minimize pain. Thus, we utilitarians also value rights, freedoms, and autonomy, but we do so because we believe that these attributes create long-term value. Other philosophies reject this indirect path as a reason to value rights, freedoms, and autonomy, insisting that they have intrinsic worth. Deontologists, for example, demand that in order to be ethical, we must value justice as an end in itself. They argue that the morality of an action should be based on whether that action itself is right or wrong, rather than on net consequences. Thus, deontologists believe no one has a right to push the guy off the bridge in the footbridge problem. Libertarians, meanwhile, believe that individuals are entitled to personal freedoms and autonomy, which outweigh the goal of creating the most good possible in the world.

Utilitarianism has been in conflict with deontology, libertarianism, and other ethical perspectives for a very long time. I’m fascinated by these debates within moral philosophy, while maintaining my view that aiming to create as much good as possible is generally a pretty good path, one that can be adjusted for concerns about justice, rights, freedom, and autonomy in specific situations. For our purposes, it’s important to note that you can maintain any value you place on justice, rights, autonomy, and freedom, and still find useful strategies here. The decisions recommended by utilitarianism usually align with those of most other philosophies because they share the goal of doing more good and less harm. When theories conflict, it is because of their contrasting views of morality, which I’m not interested in trying to resolve. It’s sufficient for our purposes—striving to be better human beings—to argue that many moral values have both intrinsic value and long-term benefits. And, if you have any skepticism about utilitarianism, it is sufficient to simplify the perspective of this book as being that when all other things are about equal, we should strive to create as much value as we can.

A third critique of utilitarianism is that fully maximizing utility in the world is a very tough standard against which to measure our moral decisions. Pure utilitarianism would mean valuing your pleasure and pain no more than the pleasure and pain of any other sentient being, as well as valuing the pleasure and pain of others close to you the same as you value the pleasure and pain of strangers, including those in distant lands. For virtually all of us, this is impossible. As a result, many reject the philosophy, throwing out the goal of moving toward this state with the proverbial bathwater.

As we discussed earlier, while decision researchers do not expect people to be fully rational, they use the concept of rationality as a goal state to help identify changes that will lead us toward more rational (but not perfectly rational) decisions. Similarly, utilitarianism can stand as a North Star for guiding ethical decisions—a goal state that we’ll never reach, but that can harness our energy for making better decisions. Utilitarianism serves as a useful guidepost for being better, not perfect.

Finally, one more critique of utilitarianism, and much of moral philosophy, is that it is too often based on strange problems that we would never encounter in real life. Yet “Trolleyland” does have parallels in contemporary reality. For instance, when autonomous vehicles take over the road in the not-too-distant future, they can be expected to eliminate most accidents that occur due to driver error, saving millions of lives in the process. Machine learning will help us create safer roads. But unavoidable accidents will continue, and along with them, unavoidable harm. Our cars will face dilemmas, such as whether to save its passenger or five pedestrians, and car companies will need to program vehicles with algorithms that prioritize such harms. Should the autonomous vehicle protect its passengers, pedestrians, older people, younger people (who could lose more years of life than older people), a pregnant woman (does she count as two people?), and so on?

These are real decisions that are currently being debated. Car manufacturers recognize that the owner of an autonomous vehicle is likely to prefer a program that prioritizes her and her family’s life over those of pedestrians she doesn’t know. In contrast, regulators might require decision rules that protect as many people as possible.

ETHICS ACROSS DOMAINS

I don’t know you, but my quick assessment is that you are a very good person in some domains, pretty good in others, and less good in others that you may not confide about to anyone. I can make that prediction without knowing you because you are human, and human behavior is inconsistent. People who are wonderful to their spouse may view deception in negotiation with a client or colleague to be completely acceptable.

Because it’s easier to assess the ethicality of famous people than to take a hard look in the mirror, let’s consider philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, whose moral inconsistencies journalist Elizabeth Kolbert documented in The New Yorker.20 After amassing a fortune in steel and railroads during the late 1800s, Carnegie gave away $350 million, about 90 percent of his wealth. He endowed the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Hall, the Carnegie Foundation, the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now part of Carnegie Mellon University), and more than 2,500 libraries. Carnegie also helpfully shared the reasoning behind his philanthropic decision making, including his belief that people should give their money away while they are alive and that more value is created by donating to the broader community than by leaving money to heirs. While effective altruists might quibble with some of Carnegie’s philanthropic choices, there is little doubt that his generosity created enormous value for society.

At the same time, this person who created so much value through his philanthropy also destroyed value by engaging in miserly, ineffective, and potentially criminal behavior as a business leader. Carnegie was very tough on his employees. In an attempt to bust the union at his Homestead, Pennsylvania, steel mill, Carnegie authorized his company, Carnegie Steel Company, to institute massive pay cuts. When the union rejected the new contract, management locked out the workers and brought in hundreds of agents from a detective firm to “guard” the facilities. A battle broke out between workers and agents in which sixteen people were killed. In the end, the union was destroyed and many workers lost their jobs. This 1892 cartoon captured the value-creating and value-destroying impulses of Andrew Carnegie.

A modern-day version of this dichotomy can be seen in the actions of the Sackler family. As a result of its philanthropy, this family’s name can be found on many important institutions, including the Sackler Gallery in Washington, the Sackler Museum at Harvard, the Sackler Center for Arts Education at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Sackler Wing at the Louvre, the north wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and Sackler research institutes at Oxford, Columbia, and many other universities. The family has also endowed numerous professorships and funded medical research.

Many view the same family as the leading culprit behind the opioid epidemic that has devastated American communities in recent years. The Sacklers’ family business, Purdue Pharma, launched the prescription painkiller OxyContin in 1996. The family has made many billions by marketing, and arguably overmarketing, the drug. In 2018, opioids were killing more than one hundred Americans a day, according to most estimates. Purdue is often accused of intentionally encouraging opioid addiction to maximize sales and engaging in a wide variety of unethical promotional practices. The Sacklers have also been accused of inappropriately funneling billions out of Purdue Pharma and hiding their fortune in offshore accounts to shield it from victims.21 When faced with thousands of lawsuits from cities, states, and other entities for their role in the opioid crisis, the Sacklers refused to accept responsibility and threatened to take Purdue Pharma into bankruptcy protection. Although it’s tough to quantify, it seems the Sacklers have created far more harm by selling opioids than the benefits they created through their charitable donations.

In his book Winners Take All, Anand Giridharadas argues that society too often lets philanthropists off the hook for the value destruction they cause.22 In fact, he argues that many of society’s biggest philanthropists give away their money precisely to distract citizens from noticing the harm they inflict. I find Giridharadas’s arguments to be a bit too cynical, yet I think he nicely highlights that we should judge people by the cumulative net value that they create or destroy, rather than giving them credit for an isolated aspect of their behavior. He also makes the important observation that most of us engage in some activities that create value and others that destroy it. Recognizing the multidimensionality of our behavior and caring about the value and harm we create can help us identify where change might be most useful.

Thus, we should think about our decisions as a whole, taking credit for where we do well, but also noticing where adjustments may be worthwhile. Unfortunately, we spend too little time on this latter task. We may need to accept some changes to our behavior to be more generous, making some personal sacrifices for the good of others. But in addition to sacrificing for the good of others, we can create more value by making wiser decisions. We can also create more value by thinking more clearly, negotiating more effectively, noticing and acting on corruption, and being more aware of opportunities to be better.