Chapter 3

Making Wise Trade-offs

What is more important, your salary or the type of work you perform? The quality of the wine or the taste of the food? The location of a house that’s for sale or its size? Saving money or enjoying life day by day?

Weirdly, my experience is that most people will readily provide answers to such comparisons despite not knowing how much salary they’d have to sacrifice to get more job enjoyment or how much better the location of the house is as compared to its change in size. Decision analysts tell us that we shouldn’t answer these questions based simply on which attribute feels most important to us. Rather, we need to know how much of one attribute we are giving up to gain on the other.

It’s common for politicians running for office to promise to do everything possible to make sure that “your taxes will go down,” “you can have the doctor of your choice,” “the government will protect the natural environment,” “we will have the strongest armed forces possible,” “the national debt will not grow,” and so on. Voters like these simplistic promises—at least, they like the ones that are consistent with their politics. But wise leaders realize that there are trade-offs involved: if you grow the military, spend more on social services, and reduce taxes, the national debt is bound to increase. And often, the trade-offs that would be required to fulfill a promise just don’t make sense. On many trades, we would gain very little on one dimension while incurring great cost on other dimensions. We also overlook many trades that would create value and have broad support, such as making it easier for citizens to vote.

To pick the right job, house, or vacation, or to make a great public policy decision, we need to make wise trade-offs across various dimensions. When you make wise trade-offs, you are trading up and creating value. Some decisions are easy because the trade-off is obvious. If you’re choosing between a job that you think would be challenging and fun, and one that sounds boring but would pay $1,000 more per year, it may be easy to choose the more interesting job. Tougher decisions pit one criterion against another, and the options feel similar in overall value. If the less interesting of the two jobs would pay $20,000 more per year, and you still have a bunch of college debt, for example, the decision may feel much harder because the jobs each excel on different criteria. Too often, people rely only on their intuition to make such decisions and overweight emotional criteria as a result. That is why it may well be useful to compare the choices more methodically. You might create two columns with the two options at the top, then list the criteria on the left-hand side and assess how important each criterion is to you, as well as how each option does on each of the criteria. Sounds a bit formal, but allowing your System 2 thinking to check your System 1 intuition can often help you make smarter trade-offs.

When making our most important decisions, often those with implications beyond ourselves, we’ll create more value by making wise trades across a variety of criteria. Consider Charity Navigator, an online platform that provides useful information about the percentage of donated funds that nonprofits use for overhead. Charity Navigator is an extreme proponent of charities maintaining low overhead. I agree that low overhead is a good goal for nonprofits to pursue. But, like those in the effective altruism movement, I believe that other characteristics of charities are also relevant, including their effectiveness, the amount of good they do per charitable dollar, and the integrity and generosity of their leaders. For example, a charity might have a high overhead rate because it spends money on research and competitive salaries to attract and retain the best staff, just like many of the most successful businesses. If this staff can create a more effective organization, the higher overhead might be worthwhile. As an easy-to-use metric, a focus on overhead may prevent organizations from making wise trade-offs against other important criteria, such as their effectiveness or the net amount of value that they create.

In the prior chapter, we overviewed evidence that when we evaluate one option at a time, our intuitive system guides our decision making, we make worse decisions, and we create less value, in comparison to when we compare two or more options. Lucius Caviola and his colleagues use this research to show that we pay more attention to overhead rates when we assess one charity at a time, and focus more on overall effectiveness and make wiser donation decisions when we compare charities.1 We will return to the realm of philanthropy in much more detail in Chapter 9.

CREATING AND CLAIMING VALUE IN NEGOTIATION

The simplest kinds of trade-offs we can make are limited to our own personal decisions—where to live, which job to take, etc. When other people have a say in our decisions, we often need to negotiate. In negotiation, the potential for trade-offs is widespread: we face trade-offs between the multiple issues being negotiated, between competing and cooperating with our counterpart, and in making decisions that benefit our own group versus society at large. We create value by trading off issues that are of differential importance to the different parties. These problems have been well analyzed in negotiation and game theory. However, the analysis has focused on what is best for individual decision makers alone. To the extent that you care about others and society at large, your decisions should tilt toward creating value, cooperation, and thinking about ever-broader groups.

Imagine that it is Friday evening, and you and your significant other have agreed to go out but have made no specific plans. If you’re like many couples, when you start talking about dinner, your significant other prefers restaurant A, while you prefer restaurant C. Since you are both reasonable people, you compromise on restaurant B. Over dinner, you agree to continue on to a movie. Your significant other proposes movie D, and you counter with movie F. Again, being reasonable people, you compromise on movie E. The B-E combo makes for a fine evening. But on the way home, you both realize that your significant other cared more about the restaurant choice, and the movie choice was much more important to you. As a result, the A-F combo would have been preferable to both of you. The B-E combo failed to create the value that was available from the A-F choice.

This quaint, unimportant example highlights a way of thinking about negotiation—one that focuses on value creation. A very simple principle, taught in virtually any negotiation course, is that you can create value by making trade-offs across issues. This means that any time there are two or more issues in a negotiation (dinner/movie or price/financing terms/timing of delivery), it is critical to learn how important the various issues are to all parties involved so that you can seek trade-offs. Notice that even if you haven’t bought into the utilitarian tilt of this book, you would still want to find wise trade-offs in a given negotiation so that you could create a larger pie to divide up with the other side.

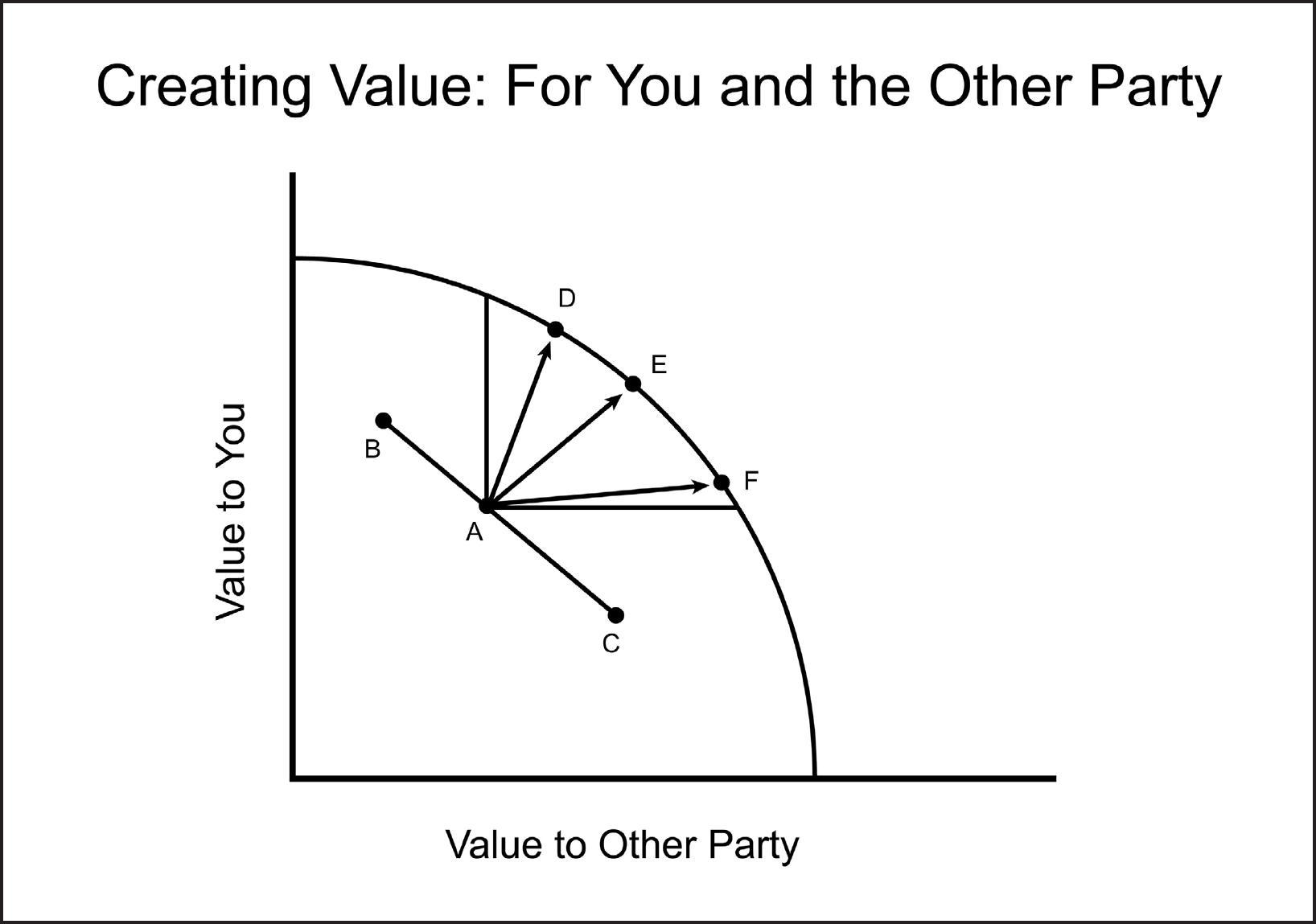

The importance of searching for trade-offs in negotiation is shown in the graph below. Based on my many years of teaching negotiation and consulting executives, I can tell you that it is common for parties to settle on deals that resemble Agreement A: the parties have reached agreement, and both are getting value from the agreement, but there are many other agreements available that would provide them with more value. Note that Agreements D, E, and F are all better from both parties’ perspectives than Agreement A, but that you would prefer D, and the other party would prefer F. This tension between you and your counterpart on claiming value often prevents the wise search for value and leaves parties with the pathetic Agreement A instead.

© 2019 Robert C. Shonk

When I teach negotiation, many students enter my course thinking of themselves as great negotiators. What they typically mean by this is that they are good at price haggling and do not keep track of how many deals they have blown by being too tough. Most of these self-described “great negotiators” have rarely thought about value creation. They often suffer from what we call the mythical fixed pie of negotiation. That is, they falsely assume the size of the pie to be carved up is fixed.

Now, many contests are win–lose, including athletic competitions, admissions to private schools, and corporate battles for market share, but in most negotiations, we have the potential to expand the size of the pie. We can do this by making value-creating trade-offs across issues so that both parties get more of what they care about most. We encourage negotiation students to create as much value as possible, or in more technical language, to negotiate along the Pareto-efficient frontier, which is defined as the set of possible agreements that exist such that there is no other agreement that would make both parties better off. Many negotiators remain concerned that if they share the information needed to create value, the other party may be able to claim more value from them, and they don’t want to be a sucker. Deepak Malhotra and I explore how you can create value while reducing the risk of losing out on the value-claiming side in our book, Negotiation Genius.2

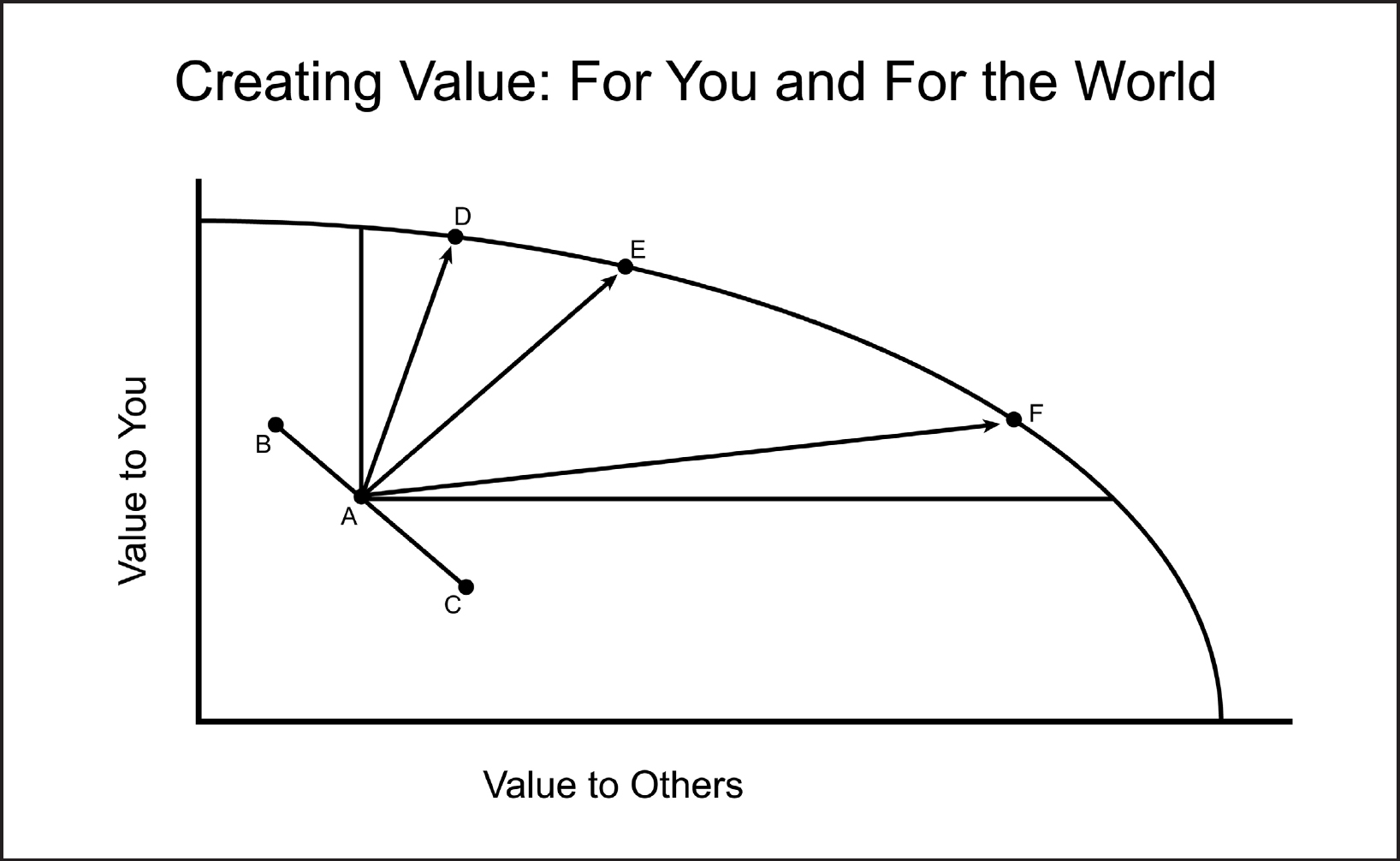

Sticking with this typical error of assuming a fixed pie, let’s look at a variation of the same graph below. Consider your current state of existence, where you are creating a bunch of good for yourself and a bunch of good for the rest of the world. In the following depiction, we will call your current state of existence “A.”

If you became less generous, you’d move from point A toward point B, and if you became more generous, you’d move from Point A to Point C. But what about the less costly and more powerful impact you can make by moving toward Points D, E, and F, where you can get more value for yourself while also creating more value for society? This chapter focuses on how you can do more good, not only by your generosity, but also by your effectiveness in moving to the northeast of this chart in how you make decisions, negotiate, and seek opportunities to find the trades that create value.

Finally, note that the horizontal axis in this representation is longer than the vertical axis (and that line A-F is longer than line A-D). This highlights that the amount of good you can do for others is far larger than the good you can do for yourself with the same level of resources. As utilitarianism highlights, a fixed sum of money is far more useful for the needy than it is for someone well-off enough to be reading this book. For our purposes, and from a utilitarian perspective, suffice it to say that it would be a shame if your concern about moving a bit from Agreement A toward Agreement C kept you from moving dramatically in the direction of Agreement E.

Even if you sometimes lose value, focusing more on value creation works out in the end. What you lose by focusing on value creation will occasionally cost you a bit, but is far more than made up for by the value you can create for others. In the process, you are using one more strategy to make the world better.

ON FREE TRADE

In the summer of 2018, I was asked by the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School, “What’s the biggest recent mistake you’ve seen in a negotiation?”3 The answer was obvious:

The biggest recent mistake I’ve seen was . . . the United States government’s negotiation with the Chinese government over trade. If you want to confront an economic competitor in a global economy, gaining leverage (by making sure other trading colleagues are on your side) is critical. In this case, the U.S. government alienated many countries prior to the negotiation, losing the power of our allies. The . . . overly simplistic and naively aggressive approach to negotiation just won’t cut it in our current global economic environment.

American trade policy in 2018–20 defines the mythical fixed-pie mindset, as it has been based on the assumption that what one side gains, the other loses. By 2016, the United States was recovering nicely from the 2008 recession and was well on its way to reestablishing its economic power. This recovery included a series of international free-trade agreements. Free trade creates value in numerous ways.4 It promotes efficiency through greater competition. It allows a country to specialize in what it is best at producing and trade with countries that can produce other goods where it lacks a comparative advantage. Due to free trade, consumers benefit from access to a great variety of goods and lower prices through competition. Free trade breaks up single-country monopolies by adding competition from outside that country. Free trade also promotes knowledge transfer and even reduces the likelihood of war, as countries rarely attack significant trading partners. Overall, free trade creates net value for all countries involved in a trade agreement. However, within specific countries, there may be losers as a result—often, industries and unions in areas where another country offers better or cheaper products.

There were multiple reasons for the United States to be unhappy with its trading status with China leading up to 2018. China had a consistent record of requiring foreign companies to enter local joint ventures with Chinese firms in order to enter the Chinese market. Foreign companies also submitted to having their intellectual property “inspected” by the Chinese government, which many U.S. officials view as a convenient way for Chinese entities to steal intellectual property. Many other countries shared such concerns but lacked the power to act on them.

While the trading regime that existed through 2016 may have created net value for both the United States and China, there was a case to be made that the existing set of agreements was closer to Point F in the graphs above and that the United States should force a renegotiation to get to Point E or even Point D. However, the United States falsely assumed a mythical fixed pie, which led the negotiations off the Pareto-efficient frontier, back toward Point A, or worse. Specifically, to try to secure unreciprocated concessions from China, America imposed tariffs on Chinese imports. Instead of concessions, China predictably retaliated with tariffs on U.S. exports to China.

If you want to start a trade war, it is wise to think about what the countries you pick your fight with will do in return. It is predictable that if China loses part of the U.S. market, China will reach out to other trading partners to replace U.S. demand. Interestingly, many of these other trading partners were annoyed with China for the same reasons that the United States was annoyed with China. Thus, any wise negotiator would see the need to coordinate trade strategy with our allies. Unfortunately, America chose to antagonize most key trading partners around the same time. As a result, many other trading partners focused on enhancing their relations with China at the very time that the United States could have benefited from presenting a united front. In the case of this trade war, the pain inflicted on China is far less than that experienced by the United States, and the value creation available through free trade was lost.

MANAGING THE TRADE-OFF BETWEEN COOPERATION AND COMPETITION

The trade war story highlights another puzzle to solve in terms of trade-offs and the global good: the tension between cooperation and competition. Let’s switch to some common choices you might confront. Should you help your peers at work succeed in their jobs or compete with them so that you are more likely to get the next promotion? Should you highlight the help you received from others when touting a success or claim the credit for yourself? These are just two examples of the very common trade-off we face between cooperating and competing.

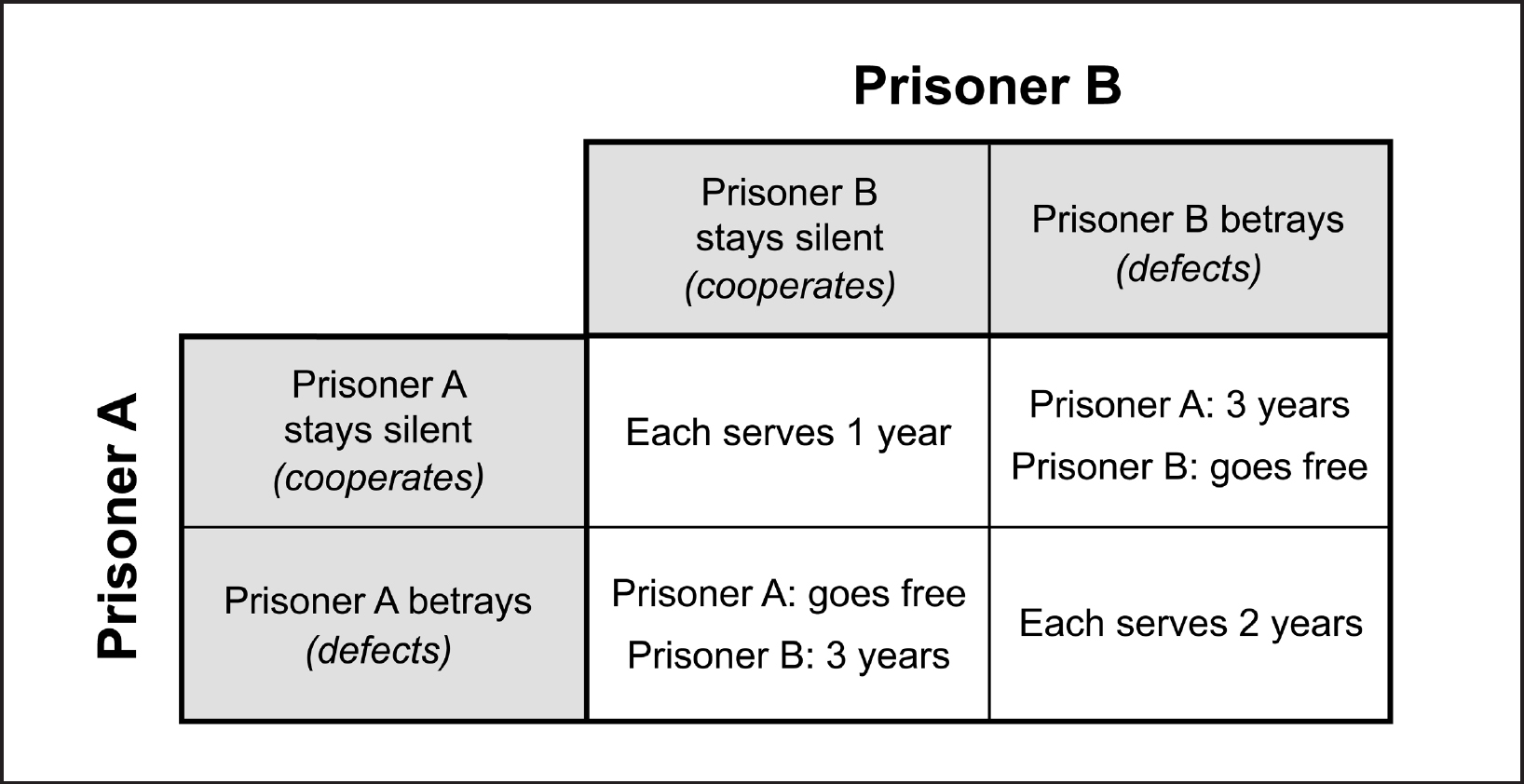

In fact, this trade-off lies at the heart of the most famous game theory problem ever created, one in which you and a “colleague” have been arrested. The police have enough evidence to convict you of a lesser crime and to send you both to jail for a year. However, the police believe (correctly) that the two of you committed a more serious crime. You, Prisoner A, and your colleague, Prisoner B, have been separated and placed in different rooms. The police have offered you a deal:5

If you confess and your colleague doesn’t, you can turn on your colleague, providing the police with the evidence that they need to convict your colleague. Your colleague will get three years in jail, and you will get no prison time.

Unfortunately for you, the police have offered your colleague the same deal (see the top figure below). They also have clarified that if you both confess, you will each get two years. You and your colleague are facing the same problem: together, you are both better off not confessing (you each get one year) than confessing (you each get two years), yet each of you is individually better off confessing, regardless of what the other party does. That is, if your colleague confesses, confessing results in you getting two years rather than one year, and if your colleague doesn’t confess, confessing results in you going free rather than serving one year. Thus, while you are collectively better off cooperating with each other, each of you has an incentive to defect, or compete.6

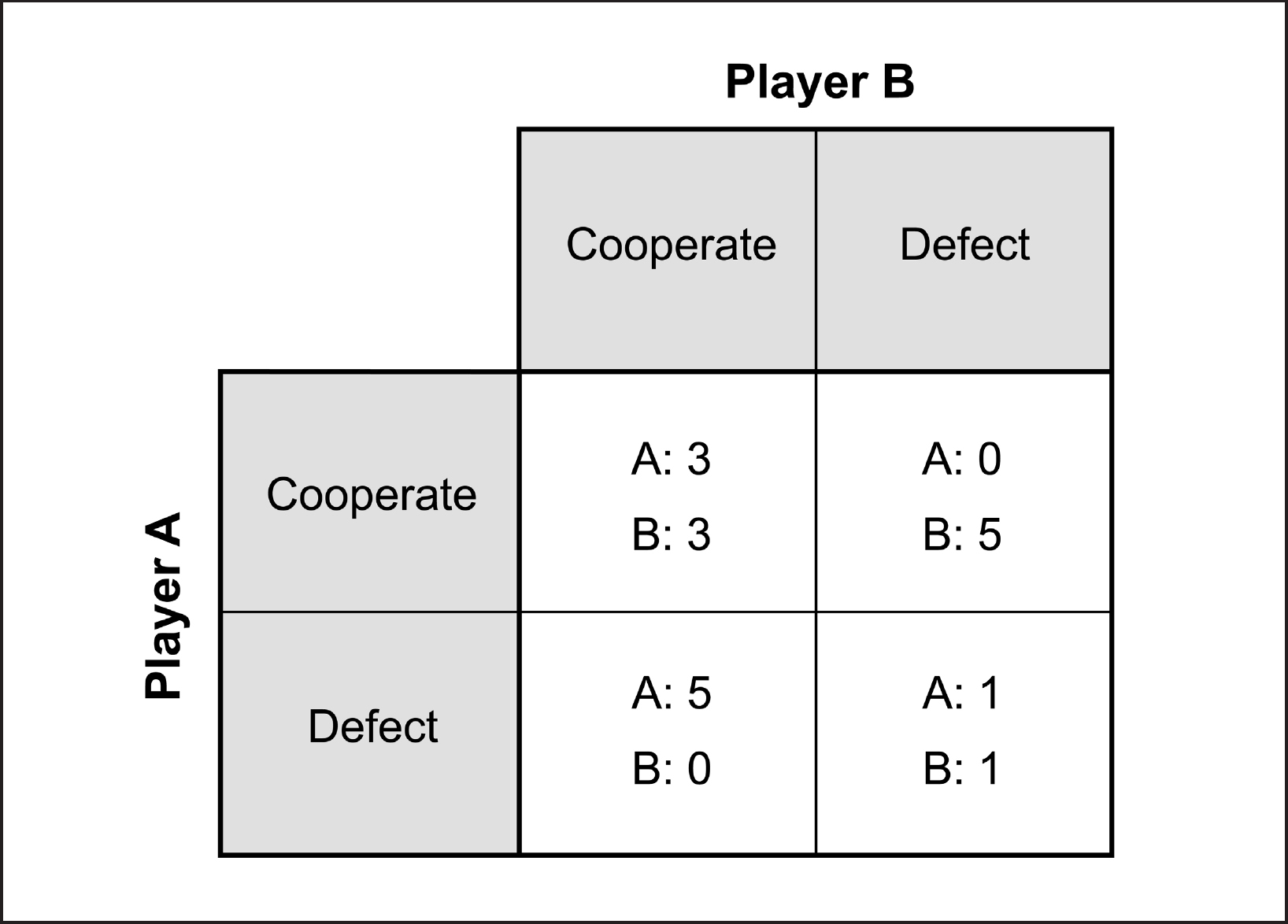

This “prisoner’s dilemma” game has become famous because it captures the essence of the trade-off between competing and cooperating. The game has become a prototype used to determine what factors affect the decision to cooperate and to identify how to think about trade-offs between cooperating and competing when you are not sure what others will do. The prisoner’s dilemma has been the subject of thousands of scientific papers. In the process, it has been abstracted to look more like the following problem (it’s useful to think of the units as money, such as dollars):

© 2019 Robert C. Shonk

© 2019 Robert C. Shonk

In many of these papers, participants play the game over and over again with the same “colleague,” and find out whether the colleague competed or cooperated on each prior trial. Would you cooperate or defect (compete) if you were playing one round of the game? How would your strategy differ if you were playing many rounds? A psychologist by the name of Anatol Rappaport advocated a strategy called “tit-for-tat” for prisoner’s dilemma games played a large number of times. This strategy called for a player to cooperate with the other player in Round 1 and then match whatever action the other player took in the prior round, for all subsequent rounds—that is, your colleague’s action in Round 1 determines your action in Round 2; your colleague’s action in Round 2 determines your action in Round 3, and so on, for as many as two hundred rounds.

Political scientist Robert Axelrod created a fascinating study to find out what strategy is most effective in multi-round prisoner dilemma games. Rather than using college students as participants (as most studies did at the time—this was before the internet existed), Axelrod invited experts on the prisoner dilemma game, namely academic social scientists, to submit their best strategy for a competition to determine which worked best. He told all potential participants in advance that each strategy would be tested against each other strategy in a two-hundred-round version of the game. Each strategy would accumulate points through the tournament and be ranked accordingly. There were fourteen entries, and Rappaport’s tit-for-tat strategy won. Axelrod published the results, and at the end of the article, welcomed entries for a second tournament. Once again, tit-for-tat won, this time in a competition with sixty-nine entries. Many additional prisoner’s dilemma tournaments have been held, and tit-for-tat, and some minor variations on it, continued to do extremely well.

But tit-for-tat is not the take-home message. Rather, for managing relationships in the real world and creating more value, Axelrod notes that the effective strategies were nice, simple, responsive, and forgiving. Nice strategies start out by aiming to create positive relationships. In iterated games, nice strategies cooperate in Round 1 and continue to cooperate as long as the other party also does. In real life, nice strategies look for the best in others and accept the small risk that not-nice people will take advantage of them. In addition, simple strategies make cooperation easier to understand than competition. Of course, being nice can also lead to being suckered. If you cooperate, and your colleague does not, you get the very worst outcome possible, but you are only suckered for one round. In the prisoner’s dilemma tournaments, some of the experts submitted strategies that went to great lengths to gain an advantage over “nice” strategies. They often got short-term gains, but did not succeed over the long term.

A third key to tit-for-tat’s success is that it is responsive: it communicates to the other party that they will not get away with competing for long. Finally, tit-for-tat is forgiving. It doesn’t hold a grudge. When the other side demonstrates new cooperative behavior, tit-for-tat is open to reestablishing an effective, value-creating relationship. Overdoing punishment can lead conflict to escalate. Tit-for-tat cannot score higher than its direct competitor. It can only do “as good as” the party it is playing against in a specific game, since it never competes unprompted. Yet it won the tournaments by consistently developing mutually beneficial relationships. While this book advocates for creating value beyond yourself, I would argue that tit-for-tat is more utilitarian than even the nice strategy of always cooperating, because it helps move the other party toward being more cooperative, which in turn helps create more joint value.

I work in a strange industry—academia. The professionals in this industry generally lay claim to the social missions of creating new knowledge and training the next generation of leaders. On many dimensions, Harvard competes with other fine universities, such as Stanford, Northwestern, and Oxford. We aggressively compete for the best entering undergraduate and MBA students. We compete to sell our executive education offerings. And we compete to be as highly ranked as possible. But one aspect of academia that I find fascinating is the degree to which we radically cooperate on lots of fronts. We share our research with competitive universities as fast as we can. We similarly share our pedagogical insights. Perhaps the most amazing cooperation occurs when one university spends a couple of hundred thousand dollars to train and mentor a Ph.D. student, with the expressed goal of placing that new Ph.D. in a job with one of our main competitors rather than hiring that student ourselves. From the perspective of almost any other industry, this choice of cooperation over competition is bizarre. Yet this norm allows academia as a whole to discover good ideas more effectively and to improve the quality of education across universities. In the process, it allows universities to create more societal value. I have always been proud of our cooperation across different member institutions.

We all experience tensions between cooperation and competition, tensions that involve real trade-offs. We don’t like to be suckered by someone who takes advantage of our cooperation. But from a long-term perspective, it is undoubtedly worth suffering the occasional one-time small loss in return for finding many long-term beneficial relationships. The key mistake we make, which leads us away from this insight, is to obsess about being suckered in our current situation when, from a long-term perspective, a life that seeks cooperation at every turn is likely to be far more effective. This is true even before we think about creating value for others. When we do think about and value the outcomes of others, the case for greater cooperation becomes overwhelming.

MAXIMIZING GLOBALLY OR LOCALLY

One common criticism of nonprofit organizations is that there are often too many of them working on the same problem. That is, there are five nonprofits doing the work that one integrated organization could do more effectively; as a result, they miss the opportunity to reduce combined overhead costs that could be used to do more good. We will return to this example when we discuss waste in Chapter 7. The more global concern, and the one I believe gets too little attention, is how this segment of the nonprofit world could be better organized to create as much value as possible for the social cause in question. A wise restructuring of the sector could do a great amount of good.

The key is to see that focusing on what is best for your organization may be at odds with creating the maximal benefit for the organization’s actual purpose. But reducing overhead by merging would mean that some organizational leaders would lose their jobs or could no longer be at the top of the organization. In addition, each organization will have strong views on minor topics, and their preferences will not always win out in the merged organization. Thus, while the recipients of the nonprofit organizations may be better off, the myopic needs of specific organizations and their members might be negatively affected. So, what trade-offs should we make between the needs of the current organizations and the recipients of the social services? I hope that the answer is obvious. In the nonprofit world, we should try to create the most good we can with the resources available. This means that nonprofit leaders should be willing to sacrifice prestige and freedom to create more effective organizations to serve their social goals. Too often, we fail at making these trade-offs.

This point about cooperation goes well beyond nonprofits. One of my favorite teaching tools is a decision-making simulation called Carter Racing, written by Jack Brittain and Sim Sitkin.7 The simulation puts participants in the role of owners of a high-level car racing team. The challenge facing the team is whether or not to race a race car, when success (placing in the top five) would create a major win in terms of getting additional funding, when failure would end the company, and when some members of the racing team are concerned about racing in the cold weather that is expected at race time.8

When I teach this simulation, executives first make an individual decision of whether to race or not race. I then send them off in groups of seven to make a group decision. When they come back to class, I ask them what goal they had as they headed toward the group meeting. Did they want to:

- gather insights from the other six members to make the best decision possible, or

- get three other members to agree with them so that they could outvote those in the minority?

Most executives admit to pursuing the latter goal, even as they recognize that the former goal is the best way to make an informed decision and achieve more effective outcomes.

One of the tasks of an effective leader is to focus all organizational units on meeting a common objective rather than on winning internal power contests. Focusing on the overall entity leads to greater effectiveness and moves the organization to the Pareto-efficient frontier, which ultimately creates value. Thus, while there may be some ambiguity about whether seeking the collectively best solution is best for you in a specific situation, looking for the best overall strategy is a good goal in life and a great way to maximize societal welfare.

We are often presented with the challenge of focusing on a smaller unit (our family, community, city, church, or department) or a broader unit (for example, the organization, rather than just your department). If our goal is to create as much good as possible, then we tend to focus too narrowly. From a utilitarian perspective, moral decisions come from asking what will do the most good rather than what will do the most good for a small group that happens to be closely connected to us.

When you consistently fail to make wise trade-offs between saving and spending money, very bad things can happen—to you. When you focus narrowly on claiming value, beating the competition, and securing a winning coalition, you may or may not do better for yourself in the short term, but there is a good chance you will suffer reputational damage. The failure to cooperate and think more globally will limit your ability to create value for you and the world. Like effective negotiators, those of us who want to achieve our maximum sustainable goodness need to harness the power of finding wise trades.