Extremadura

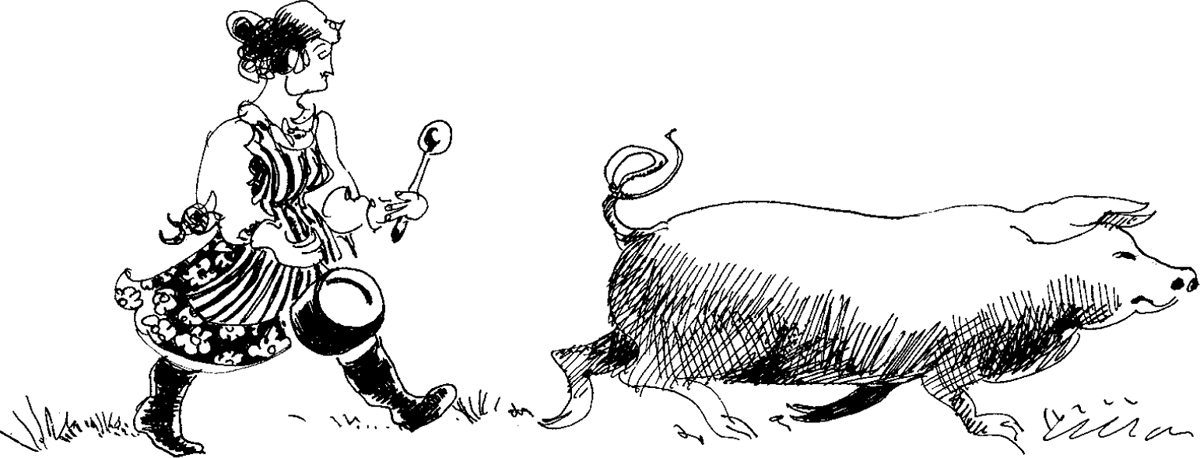

THE HUMPBACKED BLACK-FOOT PIGS OF THE Iberian Peninsula, last of the semi-wild foraging herds of Europe, fatten in autumn on the acorns of the scrub oaks of the dehesa in Extremadura, the dry lands, red and hot, that run down the Portuguese border. Their haunches, lean and muscular, are used to prepare pata negra, the salt-cured, wind-dried mountain hams of the region.

These herds, it’s fair to assume, survived in the forests of Iberia largely because of the prohibitions on the eating of pig meat during seven centuries of Muslim ascendancy. The followers of the Prophet crossed from the deserts of the Maghreb to the fertile shores of Andalusia, and set up home until the caliphate of Granada fell in 1492 to the combined might of Isabel of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon.

Thereafter Christian pork replaced Muslim lamb in the cooking pots of Al-Andaluz – and if it didn’t, the Inquisition would want to know the reason why. Religious backsliding could be identified by an unwillingness to stock the store cupboard with chorizo, ham and all the other pork products used for flavour and richness in winter stews. Many of the questions recorded in the Inquisition’s meticulous records held in Seville and Madrid have to do with the composition of the contents of the cooking pot. Questions were subtle enough to include method as well as ingredients – whether or not the meat was fried before the addition of a liquid. Until the arrival of the Moors, with their metal cooking pans, the traditional cooking pot of the Iberian peninsula was earthenware, a material more suitable for slow-simmered stews than frying over a high heat.

The name of the region itself – Extremadura, land beyond the river Duero – indicates that this is a land apart, no-man’s land, the sun-blistered, wind-blasted limits of the granite-strewn meseta, Spain’s tip-tilted central plateau.

Geographically, the territory stretches along the border with Portugal from the banks of the river Duero in the north to the Sierra Morena in the south. Sparsely populated, emigration was the only choice in medieval times for those who couldn’t scrape a living from the harsh terrain or were caught by the romance of the lands of the setting sun. The soldiers of Extremadura held the Christian line of defence against the caliphs of Al-Andaluz, and many of the conquistadores who took ship for the New World – Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro among them – were sons of Extremadura.

Culturally, the region takes its lead from the great university city of Salamanca, halfway house between Seville, capital of the Spanish Main, and Santiago de Compostela, centre of Christian pilgrimage that ranks with Jerusalem and Rome.

Travelling in a camper van in the 1970s and ’80s with my children between the ferry-port of Santander on the Bay of Biscay and across the plains of Extremadura to our home in a remote valley overlooking the Pillars of Hercules, we followed the ruta de la plata, the silver road, which runs from the pilgrim city of Santiago de Compostela in the far north-west to the great harbour port of Seville in the south. We pitched camp along the way whenever darkness overtook us, and took our midday meal in one of the little ventas, rural restaurants, where the truckers parked up in the heat of the day for a plateful of whatever was simmering on the back of the stove, the day’s ration of pulses – chickpeas or lentils or white beans – cooked in a single pot, an earthenware olla, flavoured with a chunk of ham-bone and enriched with olive oil.

At that time, our neighbours in the valley kept goats for milk and meat, a sty-pig to eat up the scraps, and ran herds of the old Iberico breed to forage for acorns in the cork-oak forest round about. While the valley’s climate was too damp to cure the hams, these were sent on donkey-back to the mountains of Ronda or, if someone’s cousin offered the service, to Jabugo in the Sierra Morena in the mountains above Seville, where Extremadura meets Andalusia.

The hams, all from the black-foot Iberico breed, packed in grey sea salt harvested from the salt flats of Cadiz, travelled up on the narrow mountain paths in paniers made of esparto-grass, prickly dwarf palms, used as cheese-drainers and mats. By the time the haunches arrived at their destination – a week or so on foot – they had already absorbed enough salt to prepare them for the next step in the curing process: wind-drying in the cold mountain air.

As a family we kept our own sty-pig to eat up the household scraps, and when the day came for slaughter – men’s business, much to my relief – preparing the meat was women’s business. I learned from my neighbours how to salt down the bacon, tocino, and melt down the fat for storage as lard, manteca, used as an enrichment in stews and to spread on bread. The main business of the day for the women was cleaning the intestines in the stream as the casings for blood sausage, morcilla, and chorizo – hand-chopped pork pushed through a hand-turned mincer, spiced and flavoured with marjoram and garlic and hung on a pole to dry.

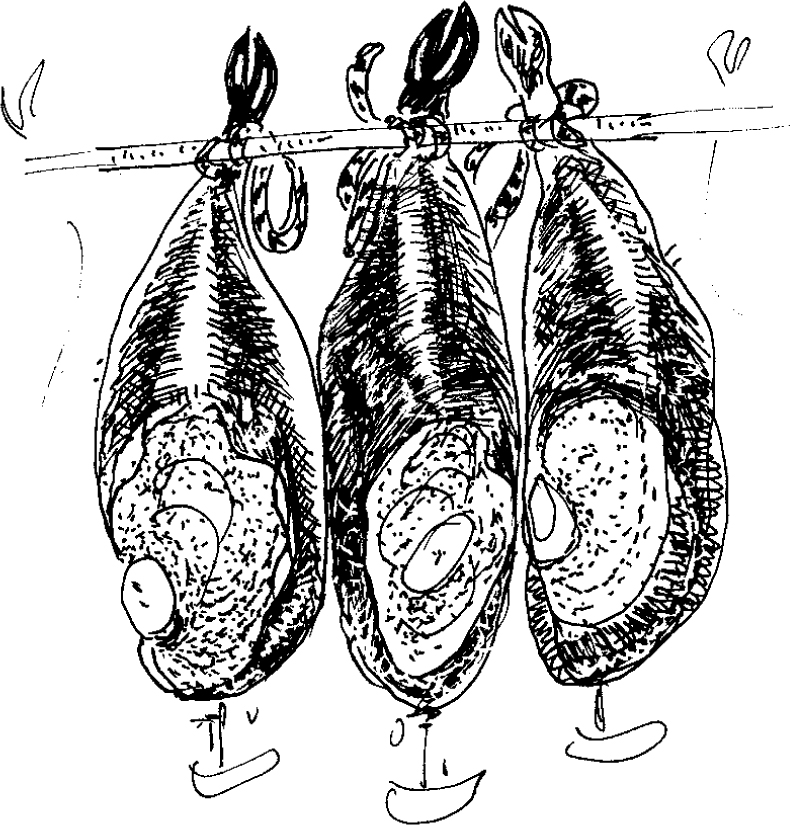

The final task was the preparing of the haunches for their journey into the mountains, the Christmas treat. A salt-cured, wind-dried ham, hung on a hook in a dry kitchen, will keep sweet and good right through the summer. The scraps and sawn-up bones were – and are – used in much the same way as a stock cube, to add depth and richness to sauces and bean-pots.

Later, when my children were grown and gone and I began to write about food and cooking, I set about rediscovering what had given me such pleasure in youth – my own and my children’s. While we in the valley salted down the meat of the annual matanza for our own winter stores, the free-ranging herds of black-foots that roamed the cork-oak forest provided an additional source of income for the self-sufficient farming community of the valley. The forest also provided charcoal for heating and cooking, and a cash-crop from the sale of the cork itself – a thick layer of silvery bark stripped from the trunks every five or seven years, depending on the age of the tree.

But that was then, and things have changed in the post-Franco years – the old dictator finally left the planet in 1975 – evident not least in the depopulation of communities such as that of our valley. Meanwhile, the introduction of the more docile breeds of domesticated pig, particularly the Large White, turned the production of serrano ham into a commercial enterprise, supplying a mass market in Spain and elsewhere. Nevertheless, the preparation of pata negra with the hams of the Iberico pigs remains very much in the hands of artisan producers, among them the curing-houses of Salamanca.

The university city of Salamanca is one of the most beautiful in all of Spain. It is also something of a gastronomic place of pilgrimage for the gourmets of Madrid, a hundred miles to the east across the plain, owing to its reputation for the excellence of the pata negra and a wealth of tapa bars and family-run restaurants in the city’s main square, Plaza Mayor.

On a fine evening in autumn a stroll through the city centre, newly polished and pedestrianised, reveals one glorious golden building behind another. The architectural outlines are simple – perfect proportions and soaring height – but a closer look reveals intricate decorative carving in the silversmith style, platero. The carvings are the work of artisans from Seville, capital of the trade with the New World, where the galleons that sailed the Spanish Main unloaded the silver and gold that replenished the coffers of the Catholic kings after the struggle to unseat the caliphs of Al-Andaluz. With the spice route closed to the east, it was no accident that, in the same year that Granada fell, Columbus set sail into the west to search out a new spice route, returning with stories of fabulous wealth in what was named the New Indies.

History dictates the gastronomy of Spain as nowhere else in Europe. It is impossible to disentangle the legacy of the past from everyday life – even now – whether in architecture, art, literature or music, but above all in her culinary habit. Even today, the gastronomy of Spain – both traditional and the modernist cuisine of Catalonia’s Ferran Adrià – owes as much to the cooks of the sybaritic Moors as it does to the wheat fields of La Mancha, the olive groves of Jaen, the fishing grounds of Galicia, the irrigated gardens of Granada, or the mountain-cured hams of Extremadura.

No one knows more about the excellence of Iberico pigs as the raw material of salt-cured, wind-dried pata negra ham than José Luis, owner and cellarer-in-chief of the city’s most celebrated ham-curing house. The enterprise exports all over the world under its trade name, Joselito, named five generations back for the founding father.

‘The eldest son is always called José,’ announces José Luis cheerfully as he orders a plateful of his own magnificent ham at a bar in the Plaza Mayor. ‘This can be confusing, so I have to have two names so that when my mother scolded me, everyone knew it wasn’t my father she was shouting at, even if it was his fault that I had stayed out late with him in the tapa bars.’

José Luis is a prosperous businessman in his middle years, charming, impeccably tailored in Savile Row suiting, if a little portly owing to his evident enjoyment of the good things of the table. He is as proud of Salamanca’s status as the oldest university in Spain as he is of the hams which – and I am in no position to argue since I’m invited to sample his wares – have no rival in all the land.

Furthermore, he continues, there’s no possibility I will be allowed to pay my own way, even though our tour of the Plaza Mayor’s many eating places is scheduled to last all evening. There’s a strong tradition of hospitality throughout the Iberian peninsula – Portugal as well as Spain – and while it’s rare to be invited into someone’s home for a meal, even as a fellow Spaniard, hospitality extends to public eating places, where picking up the bill as host is a matter of orgullo – personal pride – a rule that applies to all non-locals, men as well as women.

José Luis raises his glass in the Spanish equivalent of ‘cheers’ – ‘salud, amor y pesetas’ – a toast to health, love and money, to which I reply with the courteous ‘y tiempo para gastarlos’ – and may there be time to enjoy them. While the toast is delivered in well-rounded Madrileño, the precise speech of the educated Spaniard, my own slips easily into Andaluz, a distinctive accent that swallows the ends of the words, causing much merriment among the natives when delivered by a Spanish-speaking foreigner.

The Plaza Mayor, main square, is a handsome quadrangle of arcades, balustraded windows and perfectly proportioned eighteenth-century buildings, many of which are given over to the provision of good things to eat and drink.

Salamanca’s university was founded in 1215 – Oxford dates from 1167 – and much of the city’s reputation for culinary excellence comes from the need to satisfy the appetites not only of impoverished students but of pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela.

Since Salamanca is herself a pilgrim destination, the tapa bars of the Plaza Mayor are kept busy all year round with the provision of the little mouthfuls which come free with a glass of wine. More substantial dishes are provided for those who can afford a ración – a paid-for dish for sharing between four. Citizens as well as visitors drop in at sundown for refreshment after the day’s work, including a few slivers of pata negra. Even though it’s wildly expensive, even in Spain, there’s a fine appreciation of excellence in the pleasures of the table, and even the poorest will save up for a few slivers of the best at Christmas.

What distinguishes the hams of black-foot Iberico pigs, while no longer as free-range as they once were, is that the beasts are fed at least in part on bellotas, acorns. Serrano hams are prepared with the meat of domesticated breeds fed on grain, so the meat is softer and less dense in flavour and texture. The secret of the flavour lies in the frill of golden fat which must on no account be trimmed from the meat.

So how, I enquire of Don José Luis, do you tell if the ham on the hook in the market is really a pata negra, considering that my own experience tells me that not all Iberico pigs have ebony trotters.

At first sight, you can tell from the slenderness of the haunch, the narrowness of the ankle and the colour of the veil on the exterior fat, replies José Luis. And if you’re in any doubt, the metal tag affixed to the trotter is the best guarantee of origin. Gone are the days, he adds, when it was possible to pass off one for the other.

As for the detail, the process by which the miracle is achieved, all will be revealed when I accompany him and his compañeros of the pig-curing fraternity on a tour of Joselito’s ham-curing cellars the next day. This is an invitation of considerable generosity, since few non-professionals are allowed to witness the inner workings of a naturally secretive industry. How long the hams are left in salt, the length of time allotted before the hams are transferred to the maturing vaults, these are all a matter of skill, tradition and judgement.

Meanwhile, since the ham-curing industry guarantees a ready supply of variety meats to the tapa bars, our evening’s entertainment is a guided tour of the delicious things that can be done with the interior workings of the pig.

José Luis knows everyone in town and our progress round the square is a riot of well-wishers anxious to recommend the speciality of the house to a foreign food writer with such an admirable grasp of the native tongue. This leads to rather too many glasses of the sharp red non-vintage wines of Rioja and an inability to remember what came with it. Nevertheless, my notes on what I can remember of the lengthy tasting menu lists the highlights, each taken in a different eatery, each no more than a mouthful. The stars of the tapa show of the Plaza Mayor, I note, are chicharrones, bubbly chunks of pork-skin fried crisp; trotters and tripe slow-cooked with chickpeas and chilli, callos con garbanzos; morcilla – black pudding – flavoured with cumin and topped with softly cooked rings of onion, morcilla encebollada; frittered brains and sweetbreads – tortillitas de sesos; braised pork tongue, lengua de cerdo estofada; pigs’ ears shredded and crisped in olive oil with garlic, orejas de cerdo al ajillo; tails and snouts slow-simmered with tomato and peppers, chanfaina con tomate.

Next day, nursing a mild Rioja hangover not entirely mitigated by the cure, a tiny cup of very strong coffee with a shot of anis, I arrive for instruction in the process of curing pata negra – a considerably more sophisticated version of what happened in our cork-oak forest. I keep quiet about previous experience of the artisan hams of the valley. My Andaluz accent is already a source of amusement since everyone in Spain knows that Andalusia drinks well and eats badly – Andalucía bien bebida y mal comida, as the saying goes.

José Luis, after a restorative nip of pácharan, a particularly lethal sloe gin from the Basque country, leads the way into a vast underground cavern with serried ranks of haunches in various stages of blossoming moulds.

First, explains José Luis, I should understand that the hams of Spain, both serrano and pata negra, are unlike all other raw-cured hams in that, once salted and wind-dried, they are cellared – aged in much the same way as wine – a process that allows a thick blanket of technicolour mould to develop on the exterior of the haunch, though this shrinks to a thin veil as soon as the ham is brought back to air and light.

Preliminary salting and wind-drying takes advantage of variations in climate from one ham-curing region to another. Salamanca is particularly well favoured in this respect since the breeze in the uplands in which the hams are cured is flame-hot by day and ice-cold at night. When the hams are hung in the attics after salting, the buttery fat melts by day and firms up again at night, massaging itself into the lean. The Ibericos that forage the dehesa of Extremadura, scrubby oak forest, have the advantage of plenty of exercise, delivering lean, muscular haunches well provided with exterior fat. When a ham is judged ready for cellaring – from nine to twenty months – it is transferred to the caverns to begin the maturing process, a slow procession from one room to another according to the judgement of the cellarman.

Certain moulds – crimson, snow-white, ultramarine and ochre – are available in one part of the cellars and not in another, but each is essential to the maturing process. The larger the ham, the longer it can be matured. A ham from a well-grown beast can be cellared for seven years, improving every year.

‘We use the nose for testing,’ explains José Luis, tapping a nostril. ‘This is done by using a bone-needle, a sinew from the haunch.’ He holds up a long, thin, ivory-coloured poking-stick and shoves it into a particularly well-blossomed haunch as far as the bone.

‘Here.’

Obediently I sniff. The fragrance is sweet and delicate, a little caramelised, with a scent of hay meadow.

José Luis nods appreciatively. ‘You’re right. This is exactly the fragrance we look for. After a little practice – say twenty years – we could offer you a job.’

I agree that ham-testing would be the perfect occupation for a food writer, and in my case, could be combined with an appreciation, as a painter, for the magnificent technicolour bloomings on the haunches.

The tour is over. But fortunately for me – and the compañeros of the ham fraternity waiting in the tasting-room upstairs – a seven-year-old ham is ready for sampling. It is indeed a magnificent sight, settled in its wooden cradle in the middle of a long table round which the fraternity is already enjoying a preprandial glass of oloroso, a dry golden liquid which has already served seven years in the barrel. Sherry is matured from barrel to barrel on the solera system, picking up flavour and depth as it moves from the topmost and youngest barrel to the oldest, until it’s judged ready for bottling. Our oloroso, a gift from one of the fraternity, a winemaker from Jerez, is declared the perfect companion for a seven-year-old ham.

We are provided with an expert carver, José Luis himself. Ham-carving, he explains as he sharpens the slender blade of a long flexible knife, takes many years of experience. Twenty at least, he adds with a grin – as long as it takes to appreciate the fragrance.

There are rituals to be observed in which I need instruction. Before cutting after cellaring, two or three days must be allowed for the inside temperature of the ham to reach room temperature. After cutting, the ham must be kept as dry and warm as a newborn baby – any trace of humidity in the air can spoil even the most perfectly cured ham. Long thin hams weigh heavier than short plump hams – it’s all to do with the ratio of bone to flesh. The more a ham weighs in proportion to its size, the better it will be.

The way to carve a ham, he continues, is to start at the shoulder. When carving, the little black trotter must be pointing upwards. Only the portion of the haunch to be carved should be trimmed of skin and a little of the outer fat – not too much, as it’s the fat that carries the flavour.

José Luis wishes each stage to be appreciated in full, so I busy myself with my notebook.

Hand-cutting is much preferable to machine-cutting, when the ham needs to be de-boned, losing much of its natural character. Machine-cutting is better than no ham at all, but this is not what José Luis considers appropriate. When cutting, the first to arrive on the plate is the meat from the top cut, the tapa – the lid or covering – the best and sweetest and most buttery because of the process by which the fat is massaged into the meat. The contra – the other side of the ham, when the top has been carved and the haunch is turned over – is less fatty and the meat is darker and denser. Within these divisions, each section changes flavour and becomes less exquisitely buttery as the knife gets nearer to the bone. The hock, the last piece to be carved, is sinewy but very delicate in flavour, while the culata, the piece nearest the trotter, though well flavoured, is a little salty and suitable only to flavour the olla.

Iberico, as with all serrano or mountain hams, must be carved from the bone in short curls, lonchas. Strong men come to blows over the correct order of carving, but the cardinal rule is that carving should be with rather than against the grain. Parma ham, being softer and less dense, and therefore inferior – an opinion endorsed by the rest of the fraternity – is sliced against the grain. Once sufficient ham has been carved, the cut surface must be protected with a layer of carved-off fat and a cotton cloth, and hung in a dry current of air. If the ham is kept in the fridge, as some do who know no better, it will grow a furry green jacket in two shakes of a pig’s tail.

So how do you tell, I enquire, if what’s on the plate is the real thing?

This is easy. Iberico fat melts at blood temperature, which is about the same as a warm evening in a tapa bar such as those of the Plaza Mayor. To check that your jamón ibérico is as it should be even before you taste it, pick up your plateful and hold it sideways. If the ham sticks to the plate, it’s Iberico. If the meat drops, you’ve been sold an imposter and you should demand the return of your money.

José Luis demonstrates the truth of his words. Sure enough, the carved curls of ham, neatly spread out in a single layer, remain firmly in place on the plate. With pata negra, he continues, look first for the little white crystals no bigger than a pinhead that confirm the beast has fattened on acorns. Now pick up a curl – advice eagerly followed by the rest of the fraternity – and let it gently feel the warmth of your fingertips while you admire the burgundy transparency when you hold it to the light.

Meanwhile the carving continues. Each loncha, a ruby curl fringed with pale golden fat, is tenderly placed among its fellows on a large china plate. Pata negra, while it’s possible to appreciate it as a private pleasure, is best eaten in company, accompanied by wine and stories and the good fellowship engendered by the enjoyment of something supremely delicious.

Now it’s time to appreciate texture and flavour. Here, too, instructions must be followed. Each morsel must be delicately placed on the tongue, allowing the fragrance to reach the sensors at the back of the throat. The first bite delivers the faint crunch of the crystals. Now for the flavour, which is sweet, clean and nutty. Next comes appreciation of the texture: a little chewy but velvety and dense. The final pleasure is a little catch just behind the molars and an aftertaste of dry grass hot from the sun.

The lesson is over and conversation round the table turns to accounts of other haunches similarly appreciated under circumstances which range from romantic to practical. Wind-dried ham is travellers’ food – convenient for the pocket when slipped inside a couple of slices of sturdy country loaf with a thick brown crust from the high heat of a wood-fired oven. José Luis himself admits that he fell in love with his wife over her appreciation of a hand-carved feast of ham – pata negra, of course. Table talk is always romantic in Spain, given that there’s enough food to fill the belly. Days of plenty are doubly appreciated in a region where hunger came not only with the failure of harvest but most painfully with war – civil and otherwise – when the soldiers emptied the store cupboards, fields were left fallow and the population starved.

Next day, I have a date with Joselito’s herdsman, Juan Antonio, among the prickly holm oaks of the dehesa – the name given to the desolate lands of the west – where semi-wild herds of Ibericos, black-foot pigs, still survive in much the same way as they did in our cork-oak forest in Andalusia. Ibericos are well adapted for survival in regions where other breeds would fail, storing up fat in the good times to carry them through the lean.

The pigs of Extremadura are huge, humpbacked beasts – grey or reddish or black – stronger and heavier than our cork-forest foragers. Their feeding grounds are among stony pastures dotted with scrubby little trees with prickly leaves whose acorns, bellotas, are as fat and sweet as chestnuts. In the season on our way south, we would buy paper cones of the fresh nuts offered for sale by the roadside.

Anyone travelling through the dehesa at the beginning of autumn when the pigs are in their foraging grounds might not even notice the grey ghosts among the silvery rocks, cropping acorns and tubers, under the watchful eye of the herdsman keeping an eye out for pig rustlers and wild boar, jabalí, a love interest for the Iberico sows. Wild-boar piglets are stripy rather than plain, and any piglets born with stripes are likely to end up on the spit sooner rather than later.

There are forty million pigs in Spain, of which a million are Ibericos. Some, as I know well, forage the cork forests of the province of Cadiz, others crop the lower slopes of the mountains of Granada, and more fatten in the chestnut woods of the Sierra Morena, but the most magnificent are those that forage for bellotas and sweet roots among the prickly scrub oaks and rough red earth of Extremadura.

If the pig was philosophically important in re-Christianised Spain, it took on almost magical importance when times were hard, particularly in wartime. Even the carved-out ham-bone was handed – or rented – from one household to another when soldiers had slaughtered the livestock and emptied the store cupboard. The herdsman who cared for the pigs and followed them round their feeding grounds knew what they ate and where and when. What’s good for pigs is also good for people, making the difference between life and death.

Juan Antonio, herdsman to the Joselito Ibericos, is tall, lean, fit, weather-burned – and taciturn. He spends his days – spring, summer, autumn and winter – in the company of his pigs. Actually, he says, he prefers pigs to people. You know just where you are with a pig. All their faces are different, each has its own personality, and his pigs, he has to admit, provide all the companionship he needs.

I decide to share my pig-keeping experiences in Andalusia. Recognising a fellow pig-enthusiast, Juan Antonio softens a little. He too remembers the days when the matanza was the most important event of the year for all the family. They did indeed keep a sty-pig of the Iberico breed when he was a child. Even though he knew that the matanza was inevitable, it was not a happy event for a child who had fed and nurtured a pig from babyhood. But he was happy enough to eat the hams his mother prepared for the Christmas treat. She salted the hams and hung them to take the wind in the attic. His grandmother and the aunts also prepared chorizos, but his mother never did, though she salted the shoulder meat as well as the haunches. Certain households did certain things and others didn’t. It was a question of personality, just like the pigs.

We have established common ground. I take out my sketchbook and paints as Juan Antonio leans on his crook and watches his charges. At rest, he becomes almost invisible, immobile in the landscape with face and hat and cloak matched to the colour of earth and trees and the rocks. He begins to talk, perhaps because he feels I can be trusted not to ask silly questions or romanticise a way of life that has always been hard. In the old days, the pigs were left to roam the dehesa at will. Nowadays the terrain is roughly divided into fields by dry-stone walls topped with thorn branches, and the herds are moved season by season from one field to another, allowing the young oak saplings time to grow into mature trees. The foraging pigs in the fields are all castrated males. This, too, is different from the old days, when the herds were allowed to move in family groups. The females are all kept as breeding stock and safely corralled at home. A sow takes one hundred and fourteen days to gestate and, given opportunity with the boar, will be pregnant again on the next full moon after the piglets are weaned.

The scrub is cleaned bare beneath the trees where the Ibericos are feeding. Foraging is rotated, leaving a neighbouring field where oak seedlings are given time to gain hold. The Ibericos eat roots as well as acorns, turning over the earth and leaving it bare, but since nothing else will grow on the dehesa, the land has no other use. Acorns are available for just three of the winter months, from November to January, and the young pigs are allowed into the fields to forage when they’re ready – between a year and a half and two years – when their teeth have grown enough to allow them to crack the acorn shells.

Juan Antonio picks up a handful of bellotas, smaller and darker than the ones I remember from the cork oaks, cracks one between his teeth and shows me the nut-brown flesh. ‘This is good.’ He pops it back in his mouth and chews appreciatively.

‘What’s good for pigs is good for people. I like the bellotas but I don’t like the criadillas de tierra.’ Criadillas are truffles. Juan Antonio shudders. ‘I’m told you can take them to market and they pay good money for them in France, but I don’t like them at all, even though my grandmother said they were glad of them in wartime because they give the taste of meat when you have nothing else to flavour the pot.’

Criadillas de tierra – earth testicles – is the country people’s name for one or other of the dark-fleshed truffles that look, at first sight, like lumps of coal. One, the more valuable of the two, second only to the Piedmont white, is the Périgord black, Tuber melanosporum. The other, T. aestivum, is the more widespread summer or Burgundy truffle. I know both of them well and have, on occasion, given the right territory and time to explore, been able to gather my own. The summer truffle matures at the moment when it is of interest to both pigs and people – from May to December. The high-value black – melano, as it’s known to those who pay high prices in the markets of the Périgord – doesn’t come to maturity until late November, and has been in cultivation in Soria, not far to the south of us, since medieval times. Truffles are host-specific and symbiotic – they exchange nutrients with a suitable tree through a mycelium, a delicate web of thread-like roots. The presence of truffle mycelium on a host tree – oak, beech and hazel are all suitable for the black – is signalled by a circle of bare earth round the trunk and the unmistakable fragrance released when the subterranean tuber is ready to spread its spores.

If the truffle is close to the surface, it is possible to feel the outline through bare feet or even thin-soled shoes, while a keen nose will pick up the scent in a handful of soil. There is also a small red fly that lays its eggs on ripe truffles and jumps to safety when approached, but can be relied upon to return rapidly to its laying grounds.

The most reliable method of searching, however, is to find someone who knows the territory: Juan Antonio.

The chances of finding melano at this time of year are slim – truffles only release their scent when ripe – but there might well be aestivum in the fallow land where the holm-oak saplings are left to sprout and the pigs are not permitted to forage.

Perhaps, I enquire of Juan Antonio, he might have noticed the signs?

It’s possible, he admits, that something might be found, as long as he’s not required to smell it. The pigs certainly love the nasty little things and gobble them up whenever they find them.

He swings his legs over the rough wall that divides the foraging grounds from the fallow field and motions me to follow. Sure enough, around a sorry-looking scrub oak, the ring of bare earth is unmistakable. I can scarcely breathe for excitement. I drop to my knees and move slowly round the circle, rummaging beneath the carpet of leaves, feeling for the loosening of the earth and the slight change in temperature that might indicate the treasure beneath.

Juan Antonio watches me without comment, though I know well enough what he’s thinking – why should this absurd foreigner who knows all about the matanza want to find, let alone eat, something fit only for pigs?

My fingertips feel the telltale bump and the warmth of the earth. I close my fist around a pocket of the red dust, bend my head and inhale the unmistakable scent – a fragrance of rare roast beef, heady and fresh, and – well – to put it daintily, the appeal of the mating sow to the boar.

And here it is in my hand, a little nugget no bigger than a walnut, coal-black and rough-surfaced under its coating of earth, the treasure itself.

I cup the truffle in my hand and inhale. A truffle just lifted from its bed is irresistible. A subterranean tuber dependent for ecological success on a spore-spreader must not only be found, eaten and passed through its predator’s digestive system – pigs, people and (in my own observation) hedgehogs – but must imprint itself on the memory as well as the taste-buds. And the truffle is indeed endowed with a memory trigger. They’ve done the chemistry.

No one ever forgets the experience of where and when they tasted their first truffle, or with whom. Mine – I was a gastronomically adventurous child – was at the age of twelve at the Tour d’Argent in Paris, courtesy of my gambling grandfather, a bon viveur of the first rank, who made up for a run of bad luck at the tables with dinner at a place of his choosing with his granddaughter. The star of the show at the Tour d’Argent was pressed duck prepared at table, a performance my grandfather found much too much of a fuss. More modest in presentation was their famous poulet en demi-deuil, chicken in half-mourning, a poached bird entirely covered with fine slices of black truffle slipped between the meat and the skin. I was too young to appreciate the subliminal message, but I never forgot the fragrance.

The truffle, I decide, will make a delicious little supper this evening, when I drive south to keep an appointment in Seville.

If it were me, I tell Juan Antonio, I would eat my truffle with a loncha of your wonderful Iberico ham.

If it were him, says Juan Antonio, shepherding me back over the wall in case I find another, he would hand it over to his favourite pig. But if I want to know what his grandmother would have done, she would have put it into the olla with the beans.

And Juan Antonio would have to go hungry to bed?

Not at all. The bellotas he holds in his hand – and will take home to eat with a glass of wine while his wife prepares his supper – are as delicious as freshly roasted almonds, and just as nourishing.

I push my precious little nugget into my pocket. Later, I shall eat it all by myself with a sliver of pata negra – possibly, though not necessarily, since I fear another rough red hangover, in the company of José Luis and the compañeros of the tapa bars of the Plaza Mayor.

For now, I follow Juan Antonio’s example and gather a handful of acorns.

It’s been many years since I’ve tasted a fresh bellota. With the first bite of the crisp sweet flesh, memories of my days travelling back and forth from our home in the valley return in a rush.

Even in the 1970s, thirty years after the end of the Civil War that brought Franco to power, memories of the war were still sharp, and never sharper than at the time of the matanza. The feast of liver and lights that followed the day’s work – the men of the valley went from household to household, each on its allotted day – triggered stories of the days of deprivation.

Pepito Moreno, chief slaughter man at the matanzas of the valley, and supplier of sty-pigs in spring when his own foraging pigs produced their litters, set his herds free to roam the forest as soon as the army – Republican or Nationalist – was reported on the move.

‘We called the soldiers “bisoños” – people with needs. We couldn’t deny them. They were our fathers or husbands or brothers – some on one side, some on the other.’

If the old saying in the countryside is that hunger is the best sauce, then the cooking of Extremadura reflects the simplicity and lack of pretension of a land in which famine was never far from the door.

Richard Ford, writing in the 1850s in Gatherings from Spain, defines the flavour of Spain’s traditional olla, a one-pot meal of beans or chickpeas flavoured with garlic and enriched with olive oil, named for the implement in which it’s cooked. The beans and the fat together thicken the sauce, but the flavour comes from the bone.

‘The importance of the sauce,’ explains Ford, ‘is that it carries that rich burnt umber, raw sienna tint which Murillo imitated so well; and no wonder, since he made his particular brown, negro de hueso, bone-black, from baked olla bones, as is done to this day by those Spanish painters who indulge in meat.’

Buried among the beans for colour and sweetness, there must be dried peppers, ñora – the raw material of pimenton, Spanish paprika – and the cooking liquid is water, never stock or wine. The enrichment I prefer is olive oil stirred in at the end, when the beans are perfectly creamy and soft, but in our house in the valley it was often a spoonful of manteca, the lard from the matanza.

But the element that gives the dish its distinctive flavour and colour is mountain ham – serrano or pata negra, never mind the name – and it doesn’t have to be much, just a few scraps from the knuckle and a sawn-up length of bone.

Pepito, the herdsman of the valley, was in no doubt of the importance of the bone. In wartime, he remembers, the ham-bone was used again and again – even the faintest hint of its presence was enough to give savour to the sauce.

Myself, I’ll settle for Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s shimmering negro de hueso – I have admired it myself in the great collections of the Prado – source of that earthy fragrance that links the artists of Spain to my own and my children’s childhood.

LENGUA DE CERDO ESTOFADA (BRAISED PORK TONGUE)

Tongue, most delicious of all the variety meats, is finished in a braising sauce of onion, cinnamon and wine. For a more substantial dish, serve with thick chips fried crisp in olive oil (chips served with stews is a very Spanish habit).

Serves 6–8 as a tapa

1 kg pork tongue

1 carrot, scrubbed and chopped

1 onion, peeled and quartered

1 celery stick, chopped

1 bay leaf

12 peppercorns

salt

For the braising sauce

2 large onions, peeled and finely sliced

4–5 tablespoons olive oil

1 small cinnamon stick

1 tablespoon pimenton (Spanish paprika)

1 glass oloroso sherry or dry cider

salt and pepper

Scrub the tongue under the tap and leave to soak in salted cold water for an hour or two. Drain and transfer to a saucepan with enough water to cover generously. Bring to the boil, skim and add the aromatics – carrot, onion, celery, bay leaf, peppercorns – and a little salt. Cover with a lid and leave to simmer for 40–50 minutes, until the tongue is still firm but cooked through. Reserve the broth and drain the tongue. As soon as the tongue is cool enough to handle, slip off the skin – it comes off quite easily – and remove any little bones and extra fat from the root end. Slice thickly and reserve.

Meanwhile, prepare the braising sauce. Set the onions to fry very gently in the olive oil in a frying pan, salting lightly and allowing 30 minutes for the onion to soften without browning. Add the cinnamon stick, pimenton, sherry or cider and bubble up to evaporate the alcohol. Transfer to a casserole with the tongue slices, and add enough of the reserved broth to submerge everything completely.

Bring to the boil, then turn down the heat, cover with a tight-fitting lid and leave to simmer gently for about an hour, until the juices are reduced to a thick sauce and the meat is perfectly tender (check and add more broth if it seems to be drying out). Taste and season.

CALLOS CON GARBANZOS (TRIPE WITH CHICKPEAS AND CHILLI)

Tripe, liver and lights – rejects from Salamanca’s salt-cured Iberico trade – are the raw material of the little tapa which comes free with a glass of wine in the bars of Salamanca’s Plaza Mayor.

Serves 4–6

350 g chickpeas, soaked for 8 hours or overnight

500 g ready-cooked tripe, cut into matchsticks

1 tablespoon serrano or pata negra scraps

2–3 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

2 bay leaves

½ teaspoon crushed black peppercorns

For the sauce

4 tablespoons olive oil

1 large mild onion, peeled and finely chopped

1 red pepper, de-seeded and chopped

500 g tomatoes, skinned and diced (or tinned)

1 or 2 dried chillies, de-seeded and torn

1 glass red wine

salt and pepper

Drain the chickpeas and put them in a large pot with the tripe, ham, garlic, bay leaves and peppercorns, and add enough water to cover everything generously. Bring to the boil, skim off any grey foam which rises, and leave to bubble gently for 1½ hours until the chickpeas are perfectly soft. Some chickpeas take much longer than others. If you need to add water, let it be boiling.

Meanwhile, warm the olive oil in a frying pan, then add the onion and red pepper. Fry gently until the vegetables soften. Add the tomatoes, chillies and wine. Boil the mixture to evaporate the alcohol, and season with salt and pepper.

Now reduce the heat and cook uncovered for 20–25 minutes, until you have a thick, spicy sauce. Stir the sauce into the chickpeas and tripe and cook everything together gently for 15 minutes to marry the flavours.

TORTILLITAS DE SESOS (SWEETBREAD FRITTERS)

Offal – brains, sweetbreads and all those bits and bobs known as ‘variety meats’ – is the food of the urban poor. Country people rarely had access to any fresh meat at all, unless at the annual pig-killing or matanza, when the tender and spoilable innards were cooked and eaten immediately.

Serves 6–8 as a tapa

250 g sweetbreads

250 g pig’s brains

1 tablespoon sherry or white wine vinegar

1 bay leaf

salt and pepper

For the batter

4 tablespoons self-raising flour

½ teaspoon salt

6 tablespoons water

2 tablespoons olive oil, plus extra for frying

1 teaspoon pimenton (Spanish paprika)

1 tablespoon very finely chopped onion

1 tablespoon chopped parsley

Soak the sweetbreads and brains for an hour or two in cold water with the vinegar. Drain, rinse and bring to the boil in enough lightly salted water to cover, plus the bay leaf. When the meats are firm and cooked through – about 20 minutes – drain and leave to cool, weighted between two plates. Once cool, skin and dice.

Prepare the batter when you’re ready to cook. Sieve the flour and salt into a bowl, and gradually blend in the water and oil until you have a thin batter. Stir in the paprika, onion and parsley. Fold in the diced sweetbreads and brains.

Heat 2 fingers’ depth of oil in a frying pan. When the oil is lightly hazed with blue, drop in the batter by the tablespoonful – not too many at a time or the oil temperature will drop. Fry the fritters until golden and crisp, turning once. Serve piping hot straight from the pan, with a chilled glass of wine to cool your tongue.

MORCILLA ENCEBOLLADA (BLACK PUDDING WITH SLOW-COOKED ONIONS)

The secret to this simple combination of spicy Spanish black pudding and onion is the soffritto – thinly slivered mild Spanish onion gently fried without browning for at least half an hour until meltingly soft and golden. Spain likes its blood puddings flavoured with paprika, garlic, cloves, pepper, marjoram, coriander and cumin, with or without small cubes of pork fat. Rice is added as well. Simmering the loops of black pudding in a cauldron over a wood fire in the yard is the last chore of the traditional matanza (the annual pig-killing).

Serves 6–8 as a tapa

4–5 tablespoons lard or olive oil

500 g mild onions, peeled and finely sliced in half-moons

500 g morcilla (Spanish black pudding), cut into short lengths

salt and pepper

Heat the lard or oil in a wide, heavy pan, add the onions and let them cook very slowly for at least half an hour, until they are perfectly soft and only lightly caramelised.

Remove and reserve the onion, reheat the pan with the drippings and fry the morcilla pieces on the cut sides until they crisp a little (morcilla is already cooked, so really only needs heating up). Serve with the onion.