TASMANIANS, MANY OF THEM PROUD DESCENDANTS of the rougher end of the convict trade, are accustomed to taking life more or less as it comes with tolerance and without complaint. As inhabitants of an island a few degrees north of the Antarctic, on the receiving end of the Roaring Forties, this policy is sound.

There is, however, the problem of the great abalone robbery. Abalone is a giant limpet of considerable commercial importance when sold into the right market. The right market is not Tassie.

‘Bastards don’t even pay tax,’ mutters the man in front of me in the queue for a cab to Launceston, Tasmania’s second township and site of the island’s only airport. ‘It’s a bloody disgrace.’

If tolerance is one thing, tax-free limpet-thieving is quite another.

‘Citizens of Tassie! Let’s get real about the great abalone rip-off!’ bellows the Hobart Examiner on a ten-foot-high billboard strategically placed opposite the exit to the airport. ‘What can we do to stop the thieving crims?’ Tasmania’s state newspaper is rightfully outraged by the criminals depriving Tassie of one of her most profitable exports.

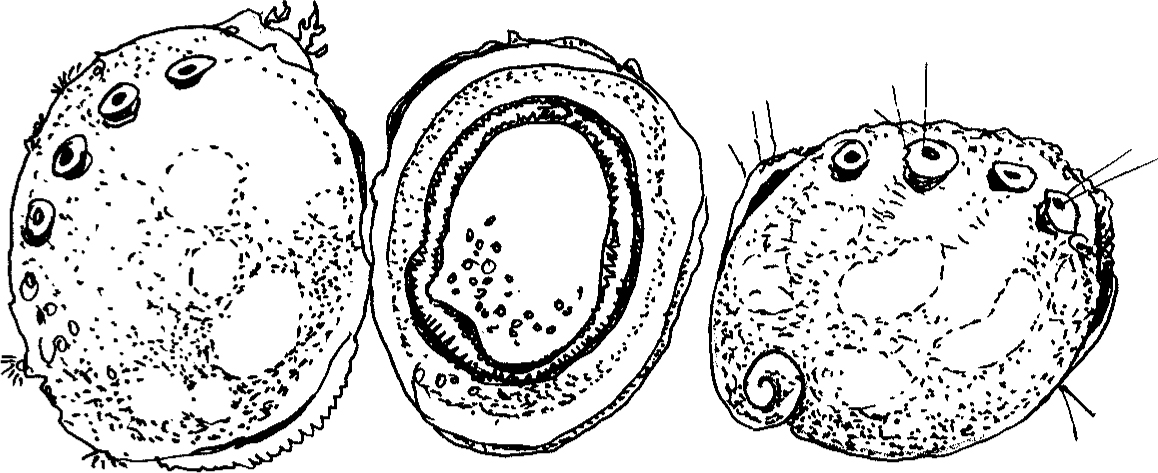

Abalone is an unusually large and succulent single-shell mollusc that attaches itself to rocks by a long rubbery foot, the edible part, in the deep waters off the coast of Tassie. The meat, fresh or dried or canned, is much prized in Japan and China, where it fetches as high a price as shark’s fin and the gluey little swifts’ nests used to make bird’s nest soup.

The islanders don’t want to eat it or even gather it, since abalone is extremely tenacious when fixed to a rock. But there are unscrupulous traders prepared to pay others to do so, and a rip-off is a rip-off. To add insult to injury, the catch is never landed on Tassie’s shores, enabling the crims to operate scot-free.

Tasmania is a holiday destination for the citizens of southeastern Australia, Melbourne, Adelaide and Sydney. The draw is partly her history – pride is taken in her convict ancestry, and Tassie was home to a particularly brutal penal colony that provided labour for sawmills to build ships for her colonial masters. And partly a wild and beautiful landscape with untamed wilderness, virgin rainforest and a climate in which fruit and vegetables ripen to perfection.

The Dutch were first to make landfall, but didn’t settle. First to till the soil were the British, arriving initially as farmers and shepherds and later as convicts and jailers. The first penal colony was established in 1802 through orders from Sydney on instruction from London. Instruction from London explains many things on the dark side of the history of Tasmania.

Darkest of all is the loss of an indigenous race of sweet-natured lotus-eaters, small of stature and golden of skin, the original inhabitants of the island.

Early settlers describe a mysterious people who ran naked in the woods, somewhat more African than their mainland cousins in appearance, amiable and tolerant, who had long since forgotten – or never needed to know – how to make fire or cure animal skins or fish in the sea. Having no need of material goods of any kind, they lived contentedly by the shore, eating shellfish and sea vegetables.

The colonisers found them unfit for any useful purpose, indifferent to the demands of their self-appointed masters and lacking in any work ethic that might be of use for logging and ship-building, the main responsibility of the colonisers. Having no need of food or clothes or money, if they didn’t wish to do what they were told, they simply melted into the woods, reappearing with equal suddenness in unexpected places, alarming the children and scaring the dogs.

The result, inevitably for the time, was that Tasmania’s First Nation was wiped from the earth without regret. Their skulls were collected by Victorian anthropologists. Their solemn faces recorded in life – blunt-nosed, dark-skinned, etched with sadness – are preserved for posterity in engravings labelled Male, Female, Infant. They left behind no carvings or artefacts or words or even thoughts, although there’s evidence that they appreciated beauty in their surroundings in a few shell-middens observed by walkers along the western cliffs at exactly the points where the view of the sunset is at its most magnificent.

The contents of these depositories, in the absence of any living witness, tell of a diet of clams, mussels, oysters, razor-shells and seaweeds. All sea creatures and sea vegetables are edible, though some make better eating than others and a good number of the seaweeds are too tough to chew. And since the original inhabitants didn’t swim, it’s probable that the Hobart Examiner’s contentious abalone escaped their attention unless washed ashore on the beach.

Those of the settlers who were sensible enough to enquire what the natives gathered from the woods learned that certain leaves, roots and seeds were used for food or medicine or both. Most widespread of these and the only one whose edibility was guaranteed by the settlers is pigweed, Portulaca oleracea, a sprawling mat of greenery with fat juicy leaves and pretty little purple flowers which develop into tiny, black, highly nutritious seeds.

The colonies had to be profitable enough to warrant support from their investors in London. Colonial governors, responsible to British politicians, had to ensure their territories earned their keep through the provision of raw materials and labour. In the absence of an indigenous workforce on Tassie, convicts were brought in to work in the shipyards that provided Sydney with ships for the ocean crossings. Supplies of timber for the yards were floated downriver from ancient pine forests logged by convict labour.

The convicts, unlike the natives, did at least speak the same language as their overseers, wore clothes rather than running around naked, feared the forest worse than the whips wielded by their masters, and if they did manage to escape, were considered unlikely to survive. The few who did were given safe haven in the settlements, accepted into households where every strong arm was a godsend, and the authorities in Sydney were none the wiser.

High summer comes to Tassie when it’s winter in the northern hemisphere. I am on the island with a brief from a country magazine whose adventurous urban readership might be encouraged to follow the tourist trail from the town of Launceston to Hobart, the capital. It’s my first visit and I’m curious to explore.

Tassie’s tourist trade has been stimulated by newly established wineries and innovative young chefs trained in Sydney and Melbourne opening restaurants within them. The clientele, on the whole, are weekenders from the mainland, where the craze is for bush-foods gathered from the wild. The locals are not convinced. Tassie may be well endowed with wilderness but those who knew how to live on forest gleanings are gone, and the incomers who replaced them are suspicious of unfamiliar eatables wrapped in paper-bark and flavoured with bush-pepper.

Launceston is Australia’s third oldest town and sits four-square in the middle of the farmland of the north. While Hobart has a reputation for prosperity and attracts investment, the same is not true of Launceston.

Once out of the airport and through the suburbs, it’s evident that Launceston’s residential centre, two-storey balconied houses forming elegant town squares, is unaltered since the days of the Prince Regent, when the extravagant architecture of the Brighton Pavilion was all the rage. Iron fretwork canopies supported on dilapidated pillars provide shade for those who take their leisure after work, catching the last of the summer sunshine and watching the world go by.

My bed-and-breakfast is in a Victorian quarter built for immigrant workers, pretty little cottages with roses round the door. Some of the cottages, says my landlady, are holiday rentals or retreats for retirees from the mainland. Front yards are bright embroideries of English cottage-garden flowers. Wooden benches provided for rest and recreation are set against billowing hedges of blue-flowered plumbago, with jasmine and honeysuckle to scent the air. Reminders of high summer are everywhere: plump cushions of marguerites, tall stands of Madonna lilies, bottlebrush bushes awash with butterflies.

People eat early in Launceston. You’re not too early at six, and later than seven-thirty is unthinkable. Tassie’s culinary habit is basically English with a touch of Scots and Welsh. Workers and schoolchildren pick up pies and pasties from the bakeries at midday, but the evening’s culinary entertainment belongs to the Mediterranean immigrants, mostly Italians and Greeks.

Shortly after seven on a quiet Monday, Launceston’s fine-dining destination, the Gazebo, is heaving with families eating pasta with seafood from the blackboard menu.

I choose a seared seafood salad.

‘Good choice,’ says the cheerful Italian waitress.

The seafood – a pyramid of tiny scallops, monster prawns, infant squid and lemony salad leaves – is as bright and sparkling as a rock-pool just filled by the tide. Whatever else happens in the watering-holes of Launceston – and I have heard dire tales of English stodge – this is high-class Mediterranean, the kind of cooking you might find at a beachside restaurant in Portofino but without the yachts and the prices.

As the blue-beaked crow flies, a mere fifty miles separates the capital, Hobart, from Launceston, and I am on my way south on a tour bus promising the gastronomic experience of a lifetime, taking in overnight stops and wineries. I am not much of a wine-buff – my interest lies in how the wine tastes with food. And I find that very good wine – which I can certainly recognise (and I have an excellent nose for anything corked) – is for those who drink wine on its own, which cuts the enjoyment by half. The only exception, as far as I’m concerned, is what Australian winemakers call the ‘stickies’ – dessert wines, particularly the sweet wines of Valencia or Monbazillac, nothing grand, which taste of summer in winter.

The island grows most of its everyday food – meat, fish, vegetables and fruit – with market gardens concentrated in the warm north and orchards in the south, while the dairy herds of King Island, a few miles off the western tip, provide milk that tastes of hay meadow as well as delicious butter, cheese and cream.

The road follows the river at first, a broad, slow-moving ribbon that makes its way through Launceston and continues on its way through fertile farmland with orchards, wheat fields and pastureland. Black and white cows and brown-fleeced sheep alternate with enclosures of emu and ostrich.

Margie, our tour guide, is also incensed by the abalone scandal highlighted in the Hobart Examiner. It is, she says, disgraceful that such a high-value export is of no benefit to the islanders, and there must be corruption in the capital. There is always corruption, in Margie’s opinion, wherever politicians are in the pockets of big business.

This is fighting talk. Margie is a staunch admirer of her namesake, Margaret Thatcher, and holds equally robust opinions. The abalone problem, she says, is no more than the tip of the iceberg in terms of loss to community coffers. The criminals – familiarly known as ‘crims’ – have stolen around seventy million Australian dollars, almost as much as the seventy-five million billed by the lawyers to the State to uphold the law. And the State, in the Examiner’s own words, has done bugger all about the thieving bastards.

The rest of the tour bus – about thirty locals in holiday mood exploring the culinary delights of their own island – agree with Margie, but with reservations. Tasmanians admire toughness and cunning and a willingness to ignore the law, as did those who survived the penal colonies. A view widely held among the islanders is that disobeying the law requires much the same skills as upholding it. And besides, says the man in the seat over the aisle, in the old days, when the island was awash with Sydney’s overflow of hardened criminals from Britain – the ones who’d committed crimes a bit more serious than stealing a loaf of bread – the real villains were the bankers of London keen to ship out an expendable, unpaid labour-force to protect their investment in the colonies.

I pull my sunhat over my ears and bury my nose in my guidebook. As the only Pom on board, and a Londoner at that, I’ve no desire to put myself in the firing line in defence of my ancestors.

Gastronomic excitements anticipated on the way south – which is really north to a Pom like me – include the catering facilities newly opened in the wineries. Tassie’s vineyards are clustered together in the warm north rather than the cold lands of the south, last port of call before the ice floes.

At midday, right on schedule, we turn in through electronically operated gates and proceed by way of an avenue of mulberry trees. Round each tree is a carpet of claret-coloured fruit gently turning alcoholic, attracting the attention of a flock of wine-sipping butterflies. Insects are as susceptible as any barfly to the mood-altering qualities of strong drink, and capable, in my observation in the cider orchards of my homeland, of behaving just as badly towards their fellow insects. There are serious amateur wine-buffs amongst our number, and I keep these thoughts to myself.

The winery is a long low steel and glass building dwarfed by huge steel storage tanks. Stretching out on either side are neatly tended vines heavy with ripening fruit. Lunch is a help-yourself buffet and will be followed, Margie assures us, by a tasting of the vineyard’s finest wines and an opportunity to buy.

Mindful of having missed my chance to lose a pound or two at Launceston’s Roman baths, I head straight for the salad buffet but am diverted by a basket of freshly baked muffins with olives and sun-dried tomatoes, both, Margie assures us, grown on the island.

The muffins are very good. I slip round to the kitchen to congratulate the chef and beg him to talk me through the recipe. The chef has ‘Surfers Do It Standing Up’ emblazoned on his T-shirt and ‘Sheilas Rule’ tattooed on one muscular biceps. Cheffing, surfing and women go hand in hand in Oz.

‘Muffins? Nothing to it,’ he says with a grin. ‘Take your standard muffin batter, mix it up with whatever you want, tip it in your usual muffin tray, chuck ’em in the oven and take ’em out when they’re done.’

This is more than I usually get when begging a recipe. Chefs are canny fellows and don’t usually hand it out step by step. On the other hand, I’ve been in the kitchen for a good few years myself and can usually pick up the threads.

The really useful stuff, however, is not the recipe itself but what the chef has noticed while he cooks.

‘Any advice,’ I enquire cautiously, ‘for Poms who reckon a muffin is a crumpet without the holes?’

Another grin is followed by just the advice I’m looking for: ‘Mix the wet and dry stuff separately, leave the mix lumpy, heat the tin before you tip in the batter, fill the dips just short of the top and bake ’em really high.’

‘Gotta go,’ he adds cheerfully. ‘Surf’s up and sheilas wait for no man.’

The wine-tasting is judged a success by our amateur wine-buffs, which is pretty much the whole busload apart from me. I sip and suck and spit discreetly, as I always do at wine-tastings. The wines are workmanlike and unassuming – to use professional wine-talk – rough enough to taste good with shepherd’s pie or cut the richness of an oxtail stew. English cooking is the norm in Tassie, and there’s no doubt that the wines, more a touch of the claret than Burgundy, suit the style.

Back in the bus, notes are compared and views exchanged, some quite heatedly. The vineyard grows Pinot Noir and Riesling, the grapes that – in considered opinions – make the only respectable drinking wine produced in the vineyards of Tassie. Tassie’s vintages, there’s general agreement, are not yet anything serious but well able to hold up their heads with similarly priced wines on the mainland.

Holding up heads with the mainland is important in Tassie. Tasmanians, in the view of the mainland – how to put it delicately? – are born with more than one head as a result of being overly affectionate with their sisters. Or, in the absence of female relatives, their sheep.

The islanders retaliate with good humour and equal indelicacy. You won’t find any Pommie-type whinging in Tassie. The first settlers, being Poms, built bread ovens and baked cakes. As a result, Tasmania’s bakeries, mostly family enterprises which have opened shops along the old drovers’ roads, bake better bread, cakes and scones than you’ll find anywhere on the mainland and – come to think of it – anywhere else where Englishwomen set up house.

If the main difficulty on the island is obtaining fresh fish – apart, apparently, from the Gazebo in Launceston – oysters are no problem and nor is farmed salmon, but ocean fish goes straight to the markets of Melbourne and Sydney and the fishermen won’t divide the catch for small-time customers. Even in Hobart, which is a fishing port in its own right, ordinary folk have to buy from the smaller boats, which means the supply is not reliable.

Island sensibilities are fine-tuned to suggestions of lack of excellence. What’s more, no one on the tour bus is in any doubt that the best butter and cream in the world comes from King Island, just off the north coast of Tassie, and the islanders prepare excellent preserves since the climate is perfectly suited to orchard fruits and ripens berries to perfection.

Bread, butter and jam – and cakes, naturally – are undoubtedly what Tassie does best. Pit-stops along the road are timed to allow passengers to sample the skill of a local bakery, always well signposted and offering takeaway hot pies and conveniently sized cookies and cakes in the form of fist-sized iced fancies, muffins, fruit slices and Anzac biscuits.

Anzac biscuits, famously baked by Australian women for their men at the front in both world wars, are another reminder of bad behaviour by the Poms. After the movie Gallipoli arrived on Antipodean screens, Poms travelling anywhere down under are well advised to avoid discussion of lions led by donkeys.

Stone-fruit orchards and berry farms are a development of the kitchen gardens of the settlers, with no need to bring plants or expertise from outside. One such is Kate’s Berry Farm, our destination for the afternoon. The bus slows and turns uphill into a side road at the hand-painted sign.

Kate herself awaits her visitors, hands on hip, outside of a pretty, white-painted farmhouse with roses round the door. Kate herself is auburn-haired – evidence on the island of Scottish descent – sturdy, dungareed, muscular and of the breed of island women who not only keep the home fires burning but chop the wood which heats the oven which bakes the bread and keeps the household fed.

Kate digs, plants and manages a hundred acres of blackberries, raspberries, strawberries and loganberries, with a side interest in a new orchard of stone fruits. Today’s visitors are in luck as Kate’s sister, her partner in the enterprise, has just picked the first crop of cherries.

‘It’s women like us who’ve always done the work on the farm,’ says Kate, surveying her domain with pride. Stretching into the distance are neatly hoed strawberry beds and rows of raspberry canes, all laden with ripening fruit.

The men, she continues, take paid work somewhere else whenever they can find it to bring in the money. On a labour-intensive farm such as this all the women – daughters, wives, sisters – work. Most of the crop is sent fresh to market, but in times of glut, what cannot be sold is frozen for the time of year when the plants are dormant and there’s time to prepare preserves. In the old days this had to be done straight away or the fruit would rot. Freezers are a godsend – an enterprise like this wouldn’t work without them.

All business takes place in the farmhouse’s front parlour, where guests can take a cup of tea with a home-made scone or a slice of cake. In the cold months, when there’s time to do other things, Kate’s mother makes the jam, and her sister makes the ice cream to sell to visitors in the summer. Kate’s Berry Farm ice cream is famous all over the island, exported to the smart restaurants of Hobart and Launceston, including the Gazebo.

The latest addition to Kate’s botanical mix are apple-tree clones.

If we don’t mind a short walk, Kate will take us on a tour of the glasshouse.

Our hostess is as proud of the lines of identical young shoots cosseted in the greenhouse as a mother with her newborn baby. Their living space is tightly controlled and growth restricted until they’ve grown into tiny trees and look like bonsai. The clones don’t like being handled. There’s no need to repot or replant until they’re strong enough to take the stress.

Stress is the new buzzword among Tassie’s producers. Word has spread from the growers of the Mediterranean that fruits and vegetables subject to stressful conditions are sweeter, denser-fleshed and more fragrant than those grown in greenhouses under perfect conditions. In Sicily, for instance, tomatoes produced under extreme conditions – minimal watering, poor soil and constant battering from wind and sea – can be sun-dried in half the time it takes elsewhere.

The little apple trees have a bright future, Kate continues. Bug-resistant and capable of producing perfect fruit throughout the growing season, there are opportunities for export worldwide. China has just discovered apples and can’t get enough of them. No question but cloning is the future. Cherries will be next, and maybe even peaches.

‘Time for chow!’ shouts Margie, poking her head through the door and interrupting Kate’s reverie.

Chow is what we are here for. We follow Kate into the new tearoom, a large airy addition to the front of the family’s home. Today there is a choice of home-baked scones to spread with thick yellow King Island cream and Kate’s mother’s award-winning raspberry jam. There are also apple slices with a jug of home-made egg custard, or lamingtons – coconut-dusted squares of chocolate cake – to eat with a scoop of freshly churned strawberry ice cream made with berries picked that very morning. And to cheer us on our way on the bus, a pound or two apiece of the beautiful dark-red cherries.

On our return to the bus, cheeks bulging, I slip into a vacant seat next to a well-upholstered middle-aged woman travelling alone like me, who has been partaking of Kate’s lamingtons with particular enthusiasm.

Her name is Muriel and she is indeed an expert on what can be considered Australia’s national cake. The cake’s invention, continues Muriel, can be credited to Lady Lamington, wife of a Governor of Oz in the days of old Queen Vic. There’s an affection for British royalty in Tassie, though this does not extend to British politicians responsible for the carnage of both world wars in which so many of Her Majesty’s loyal subjects came to grief.

I must not take such references to heart, she continues kindly, since it’s well known that many English soldiers suffered the same fate. I agree that this is true. Anzac biscuits and lamingtons are just two of the many reminders of wartime that pop up when nobody’s looking.

We move to safer territory, recipe-swapping, and embark on an in-depth discussion of whether or not a drop of vinegar or a pinch of salt increases the volume of the whisked egg whites when baking soft meringue for a pavlova. Muriel goes for vinegar and I vote for salt. Passion fruit is a must for the filling; kiwi fruit can only be considered acceptable in New Zealand.

This evening – the high spot of the journey – is a night in a lodge in the wilderness, convict territory.

To prepare us for the experience, Margie decides to alert us to the perils of the wild lands of the west with a dissertation on what really happened in those far-off days when Tassie’s cuisine was not all about strawberry ice cream and chocolate cake.

Let there be no misunderstanding: the convicts were starving so they ate each other.

Never mind if nobody else wants to talk about it; Margie considers it her duty to do so.

Teachers don’t talk about it in school, but it’s there for anyone to read in the diaries, the stories people kept in a locked box under the family Bible so nobody knew the truth.

And this, proposes Margie, is a truth that needs to be acknowledged, whether people want to believe it or not. Much as Nelson Mandela obliged his nation to acknowledge both sides of the story, truth and reconciliation is a two-way conversation.

‘We all know what we did to the people who were here before us. What we don’t want to know is what we did to ourselves.’

Margie offers this insight into island history, she continues, because the blame goes both ways. Feed a man on slops not fit for pigs and make him work till he drops and he’ll die. And if he doesn’t die, he’ll eat whoever dies ahead of him. And if he’s not yet dead, he’ll help him on his way.

‘If you treat a man worse than a dog he’ll behave worse than a dog. The ones who managed to escape into the forest had to eat to live.’

We are still and silent, hoping the story will end right here. It doesn’t.

‘What else could they do? What would any of us have done?’

We hope the question is rhetorical. It isn’t.

‘First they took out the outsiders, then the weaklings, and then it got so bad none of them slept at all in case they woke up basted on the barbie.’

Margie waits for a reaction to the joke. Nobody laughs. Basted on the barbie is not what any of us would wish to wake up to.

‘What we need to acknowledge is that the ones who got out were cannibals and everyone knew it. Any of them could have been your granddad or mine.’

Margie takes a deep breath and returns to the fray. She is not a woman to let us off the hook just yet. The story has a happy ending – of sorts. The last ship to be built was stolen by the last of the convicts, who sailed the vessel all the way to the coast of Chile. This was all the more remarkable since the ship’s stores were no more than were sufficient for the short voyage round the coast to Sydney.

The story doesn’t end here. As soon as the ship docked by the quayside in Valparaíso, the Spaniards clapped the convict crew in irons and sailed them right back. Meanwhile, word got out and by the time the ship sailed into Sydney harbour, the crowds went wild and carried the convicts up to the courthouse in triumph. The judge congratulated all present on an excellent result, everyone went home for dinner and the delicate subject of the ship’s stores was not mentioned at the time or thereafter.

What happened can be taken, says Margie, with a sideways glance at me as the representative Pom – I’m used to this by now and react with a cheerful wave – as a prime example of Aussie virtues of resourcefulness and willingness to flout authority. This is as much a part of Tassie’s true identity as the jokes about growing two heads.

Laughter breaks out. The atmosphere lightens just in time for our arrival at our billet right in the middle of the very forests through which the cannibal convicts escaped.

Sunsets are spectacular everywhere on the island, but in the west, a coastline rimmed by pink granite cliffs capped by dense green forest beneath which blue waters churn white, the sun drops like a stone in a blaze of ruby and gold to the end of the world.

The stormy west coast is mountainous, heavily forested and still sparsely inhabited, attracting backpackers and nature-lovers to camp out on the beach or take advantage of the little settlements of rough shelters left over from the days of the convict shipbuilders. One or two of the abandoned settlements have been converted into boutique hotels, where adventurous chefs from the mainland are experimenting with forest gleanings.

As soon as the bus turns off the highway on to a bumpy forest track through eucalyptus woods, it comes to a halt at a pretty whitewashed lodge surrounded by a cluster of log cabins. When we descend from the bus and make our way into the lodge to collect our room keys, Margie has an announcement. There is news, both bad and good.

The bad news is that the chef is away on the mainland at a bush-tucker conference, where his expertise in forest gleanings is expected to cause a sensation. The good news is that, to make up for any disappointment caused by the unavailability of the featured expertise, drinks are on the house and dinner is on the barbie.

Mention of the barbie gives pause for thought. But with good humour and Tassie’s appetite for indelicacy restored, the announcement triggers a short burst of tasteless barbie jokes.

Dinner on the barbie, Margie continues with a frown at the more unruly of the jokesters, will feature hamburgers and sausages with – accompanied by a quick glance in my direction – a vegetarian option.

I laugh appreciatively as a demonstration of a Pom’s ability to take a joke.

‘Good on you,’ whispers Muriel, patting my hand. Muriel is an enthusiastic admirer of The Two Fat Ladies, recycled on loop on Tassie’s TV station. When I admit to a passing acquaintance with the famous ladies, both sadly deceased, our friendship is sealed.

The mood among the group is further lifted by cans of cold beer and glasses of chilled white wine embellished with small blue flowers. These I know to be a member of the flax family, one of the few edible plants recognised by the settlers, valued for its oily little seeds as a source of frying-oil.

Muriel, asked for confirmation, agrees that this is indeed so, although her mother told her that pounding the tiny seeds was hard work for little gain. Her grandmother, she adds, used the fibrous stalks for weaving sturdy linen cloth of a far higher quality than is available today.

Refreshed and cheerful, the company disperses to inspect the accommodation in anticipation of unlimited free drinks and a hot meal of recognisable provenance.

The cabins have been comfortably modernised and equipped with en-suite shower rooms. A shower is more than welcome, and by the time I rejoin the group, the party is already in full swing. Inspecting the offerings on the barbie, I skip the meat and go for the vegetarian option sizzling in a pan set over the coals. This, a combination of eggs, cream and greens cooked like a Spanish tortilla, is dished up on a thin sheet of paper-bark. This is the only forest gleaning – other than the flax flowers now in evidence as pretty little arrangements on the tables – not subject to government inspection unless certified by an expert such as the absent chef.

Looking for somewhere to sit and eat my portion of frittata, I see Muriel wave me to her side, patting a vacant place on the bench.

‘Sit here, my dear, and tell me all about yourself and why you’re here.’

I explain about forest gleanings and how much I had been looking forward to sampling the chef’s much-praised menu on behalf of the sophisticated readership of Country Living, the magazine to which I contribute a cookery column. The magazine is popular in Tassie and Muriel is pleased by the connection. This exchange pleases us both, the frittata is very good, and I retire to my bed under the eucalyptus trees to the strains of ‘Waltzing Matilda’ rendered by a male-voice choir that would not have disgraced itself at a sing-along in my local pub in Wales.

I wake just before dawn. My fellow explorers are still asleep, so I set out in the direction of the ocean with my sketchbook, intending to catch the sunrise. In the forest around the cabins, my bird-watching binoculars pick up the quick movements in the branches of unfamiliar birds with familiar names – pink-breasted robin, forest raven, magpie-lark. Once out of the woods, the landscape opens up into rolling dunes in which sunburst clumps of enormous grasses bunched together like Martian wedding-bouquets have found a foothold in the sand.

The grasses have needle-sharp tips, tearing flesh and skin. I’m glad to reach the safety of the shoreline. In my days as a botanical and bird artist, I spent many happy hours at the Natural History Museum in London, where I made drawings of the stuffed birds and animals on display. Among the panoramas of Australia’s marsupials, I made a particular study of those that had vanished soon after the settlers set about eliminating the competition. The most haunting of these was the Tasmanian Wolf, the island’s largest predator, last of its kind, snarling from behind the glass at the species responsible for its fate.

I tread cautiously, conscious of reports of recent sightings of a hyena-like creature rattling dustbins in urban backyards. The Hobart Examiner, carried with me on the bus as a source of more up-to-date information than my guidebook, indicated that abalone thieves were not the only source of anxiety among the populace. Tasmanian Devils had to be hiding out somewhere, possibly right here.

Muriel greets me with some anxiety on my return from my dawn raid on the flora and fauna to join the breakfast queue. She too had been worried about the possible presence of man-eaters in the woods – two-legged or four – and I am happy to have found a friend.

Better still, Muriel promises to send me her prizewinning recipe for lamingtons as soon as she gets home, and I, in turn, promise to include it in my column, editor willing. Editors, we agree, are as bad as tour guides when they get the bit between their teeth.

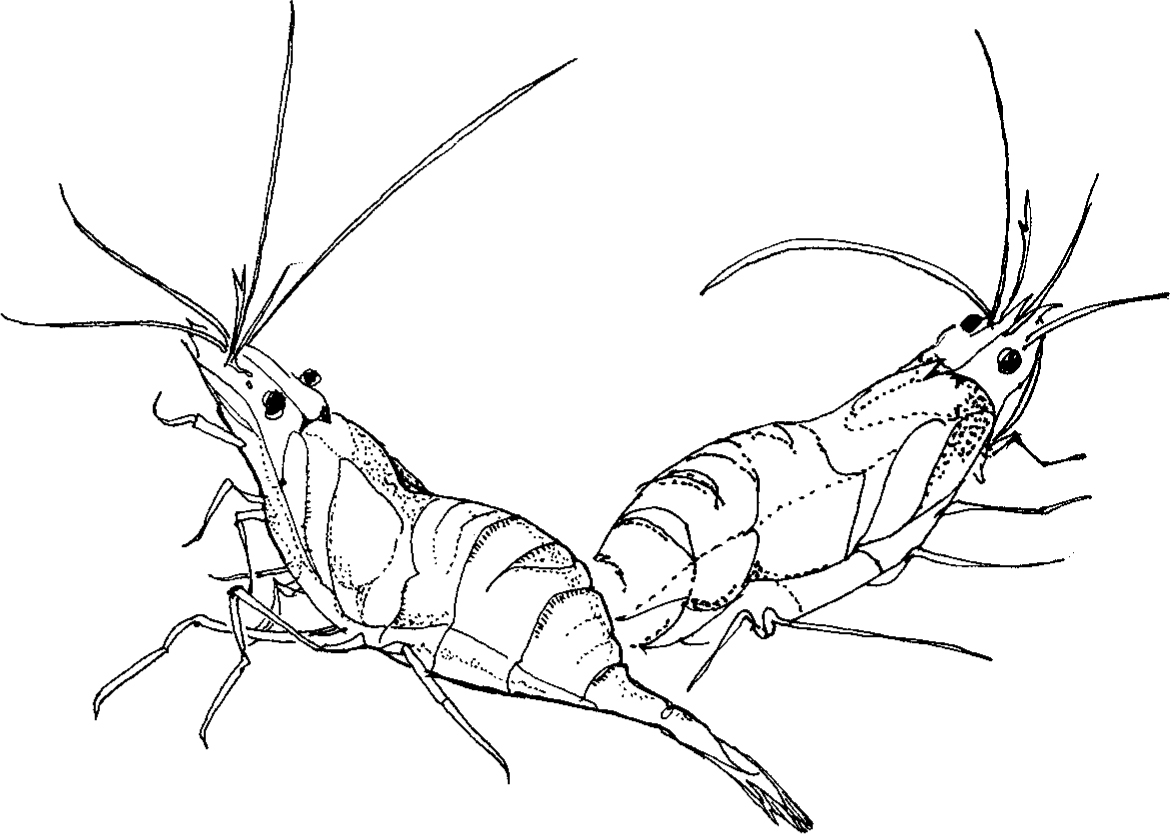

We are on our way bright and early in the bus, rattling back to the main road through the eucalyptus forest and down the coast through fertile farmland until we turn towards the ocean. Today’s excitement is Jim’s Oyster Farm and we have a date to go out on the oyster flats to collect the raw materials of lunch with the proprietor himself.

Muriel is not convinced by the notion of eating anything raw, let alone alive and quivering, and is hoping for something in the way of oyster fritters, or possibly oysters in cheese sauce bubbled up under the grill, as her mother prepared them on the rare occasions when wild oysters were available in Hobart. Oyster farming has greatly improved the availability of fresh oysters, so she is looking forward to recreating a recipe from Constance Spry for macaroni cheese with oysters which she remembers from her childhood in the 1950s.

I, on the other hand, like my oysters as nature delivers them, freshly opened on the half-shell with a squeeze of lemon and a fistful of Black Velvet – a pint of Guinness and champagne in equal measure – while perched on a high stool at the bar in Wheelers in Soho in the old days, when the world and I were young. We all have our memories, and this is mine.

Right now, decanted from the bus, we are braving the windswept estuary to meet the proprietor of Jim’s Oyster Farm. Margie has already put her charges in the picture. Supplier of the most succulent bivalves ever tasted to eager customers as far away as Sydney and Melbourne, Jim is a hero whose mission is to change the world. He may be a man of few words, continues Margie, and he doesn’t talk about himself, but even though he may not wield financial muscle or make speeches or lobby politicians, what he does is already a game-changer among those who do the real work of farming the sea.

The man in question – arms akimbo over his oilskins, luxuriantly bearded, weather-beaten and young for a man who has already achieved such a formidable reputation – is leaning by a battered hut with ‘Oyster-shack – visitors welcome’ roughly scrawled in blue paint above the door.

Tassie’s oyster farmers – Jim himself and a few hardy entrepreneurs established along the coast – co-operate with the tourist industry by offering trips to the oyster beds to sample the shellfish freshly shucked in situ. The idea has been a success. Popular with the tour-bus operators, it provides an additional source of income for the oystermen both in and out of the tourist season.

First we are to inspect Jim’s oyster nursery, a line of tanks in the shed.

Jim breeds his own stock, harvesting the tiny spat – infant oysters no bigger than a pinhead – and coaxing them tenderly to toddlerhood, moving them on to the flats only when conditions are right.

For a man of few words, Jim is surprisingly eloquent when it comes to baby oysters. Young oysters don’t like sudden surprises – anyone who understands the oyster’s natural life-cycle can see the stress-marks on their shells. They’re like children, not ready to leave home until they’re teenagers, and even then you have to keep an eye on them.

Now, for those of us who wish to take advantage of the authentic experience of oyster gathering, our chariot awaits. Jim quickens his pace as we reach the oyster-barge. The vehicle, a rusty platform resting on tank-treads, is clearly his pride and joy.

‘It may be ugly but it does the business,’ he says, patting what looks like a steering wheel with obvious affection. ‘We modelled it on a D-Day landing craft in the movie with Tom Hanks.’

We climb aboard, arrange ourselves cautiously on the wooden benches that line the sides, the engine splutters and the vehicle moves forward with surprising smoothness on to the mud flats without a shudder.

I take out my sketchbook and settle back contentedly to record the scene as best I may – never mind that the paper is already speckled with droplets of rain, this is what I came for, an experience I can write about and the readership will love. I am already working out the shape the article will take, describing in my head the wild beauty of the place, seabirds sailing overhead, the silence of this windswept estuary between reed beds and wooded hills and the jagged outline of twin headlands, the distant murmur of waves breaking against invisible rocks.

Spars of ancient shipwrecks punctuate the muddy shoreline among the reed beds, reminders that this is the final resting place of the Roaring Forties, the winds that sailors dread. For those who survived to make landfall, Tassie is the last port of call before the ocean turns to ice. One of our number, an experienced yachtsman, tells us that, even with modern navigational aids, ships lose all knowledge of where they are. There are stories of shipwrecked sailors convinced they’ve made landfall on the shores of Africa.

We reach the water’s edge. Jim cuts the engine and waits for his passengers to hear the silence.

When he speaks, his voice is soft. ‘Now you can see it as we do. This is who we are and why we’re here.’

As if to confirm his words, the sun – until now no more than a soft glow on the southern horizon – breaks through the bank of cloud and turns the ocean into dancing pools of light.

‘We chose this place, just as the Old Ones did before us. We come for the beauty of it, the cleanest waters, the freshest breeze.’

When he speaks again, he’s smiling, no longer the taciturn fisherman reluctant to engage in idle chitchat, but a man who knows his place and finds it good.

‘Sometimes I come here when there’s no need to work the beds or gather the crop, and stand on the edge of the ocean where the Old Ones stood, and feel their presence, and know just as they did that the world is beautiful and strange.’

Another pause and a smile, broader this time. ‘And of course we come here for the oysters – the best you’ll ever taste.’

Laughter greets this sudden flash of salesmanship. The spell is broken. Jim swings over the running board, hauls up a netful of rough-shelled, saucer-shaped bivalves, takes a head count of his passengers, removes a short-bladed knife from a holder on his belt, and begins to shuck.

One by one his passengers accept their offering, tip back throats, and swallow. I am last to receive my shell, preoccupied with tucking away my sketchbook safely in my pocket.

‘Here. Taste.’

Jim leans towards me, smiling. Gently cradled in his outstretched hand is an opened oyster on the half-shell, pearly and luscious and almost translucent. The flesh is soft and sweet and salty in my mouth, and the taste is creamy and silky and a little metallic, incomparably delicious.

Jim sees the pleasure on my face, and laughs.

‘That’s good.’

The engine ignites, our companions are waiting and the rain is falling in earnest.

Later, back at the rearing shed where the infant oysters are coddled in their tanks, he finds me. Muriel has told him I’m writing an article for a magazine. Tourism is important to the oyster farmers and he wants to make sure I get the story right.

‘It’s not only what we can do for the oysters but what they can do for us. They teach us to be patient. They come to maturity in their own time, reminding us to enjoy what we have, of our good fortune in living here in peace and tranquillity in this beautiful place.’

The future is as uncertain for the farmers as it is for the fishermen. ‘Everyone knows what’s happening out in the wild. Everyone in the industry, wild or farmed, knows it’s bad. And everyone knows what needs to be done.’

He shakes his head. ‘We can all see the changes. We see it in the estuary when we look at the oyster shells. We can read what’s happening out there like a book. We all know what works and what doesn’t. And we know that if what we do works for us, it works for the oysters.’

When he continues, his voice is sombre.

‘It’s not ignorance. It’s not that we don’t understand what has to be done. But we have to take action right now, before it’s too late. The technology is already in place for farming the seas and restocking the wild.’

Jim’s enterprise is already breeding scallops and bringing on young lobsters for release into the wild, and, he adds, there’s work being done in the North Atlantic on turbot and cod. If the sea is farmed in ways that don’t wreck the seabed or poison the oceans or interfere with breeding in the wild – and there’s no doubt it can be done – fish stocks will restore themselves with or without human assistance.

Marketing is the key. As long as farmed fish is seen as inferior and restaurateurs continue to list line-caught and wild as a desirable element in the seafood they sell, things won’t change.

‘There is a middle way. Salmon farming has moved in the right direction – a lot of it is now free-range and organic. We start our own young salmon in the shallow water in the estuary and then move them gradually into big pens in the ocean where they swim against the tide. With the marketing it’s a matter of how you see it. Everyone accepts rope-grown mussels and no one expects wild oysters, so we know it can be done.’

There is also a need to bring farmed fish to market – not only oysters and mussels – at a price that makes it uneconomic to source them from the wild. Abalone is a case in point. If there was enough farmed abalone to satisfy the market – and no one has yet worked out how this can be done – there’d be no money in stealing and the thieves would vanish overnight.

Farmed scallops are still expensive to produce and sell, but one day – not this year but maybe next – oyster farmers will be able to bring farmed scallops to market at a price which will send the dredgers packing.

More controversial is the farming of seahorses for export to China’s oriental medicine trade. Dainty little creatures with long snouts and enquiring eyes that float upright among coral reefs, seahorses are already being successfully grown in tanks in disused warehouses by the quayside in Hobart and sold at high prices into an ever-expanding market. The problem, much like the trade in rhino horns and elephant ivory, is that seahorse stocks are already seriously depleted in the wild, and once they’ve disappeared from the wild, any hope of using their charms to encourage conservation of their habitat will soon vanish altogether.

‘We need to do what we have to do and we need to do it now – all of us, all over the world, or those who come after us will never forgive us.’

Jim’s impassioned plea is still ringing in my ears as we reach our final destination, the waterfront at Hobart. By the end of the journey, we are no longer a busload of strangers but family. We will all miss Margie, but her message has been taken to heart. I am no longer the alien Pom but an honorary Tasmanian, as will soon be confirmed when I take a glance in the bathroom mirror this evening and find I’ve grown two heads. Muriel has acquired a dozen of Jim’s finest and is already planning a party to sample her macaroni dish and promises a full account of its reception.

The Hobart waterfront sparkles in sunshine. I provide myself with the latest issue of the Hobart Examiner and settle down at a harbourside café for a slice of home-made cheesecake and a cup of strong English tea.

Hot news in Hobart is that the harbour’s deep-water dock is now open for business and will be celebrated by the arrival this very evening of a three-thousand-passenger cruise-ship. The visitors will be welcomed with a brass band, an exhibition of sheep-shearing and a market with local produce, as well as free tastings of the best the wineries can offer. This is my last day on the island; I can live without the wine and, as a long-time resident of shepherding country, have witnessed enough sheep-shearing to last me a lifetime.

The inside pages of the Examiner bring news of a matter close to my heart – and by association, I hope, the magazine’s readership. A truffle-oak plantation has come into production after seven years of anxious expectation. Truffles, a high-value crop for those who have the patience to wait, require the restoration of woodland, even if the trees are not native.

It is confidently believed, the paper reports, that the tubers – melanosporum, the Périgord black, second in value only to magnato, the Piedmont white – are of sufficient quality to fetch high prices as far away as Italy and France. Seven years is a long time to wait for a commercial crop to come to maturity, and even then, in the Examiner’s opinion, such time-wasting methods of production may not be advisable or even excusable. There are grants available for promoting new products that might be, on mature consideration by the powers-that-be, better spent on seahorses.

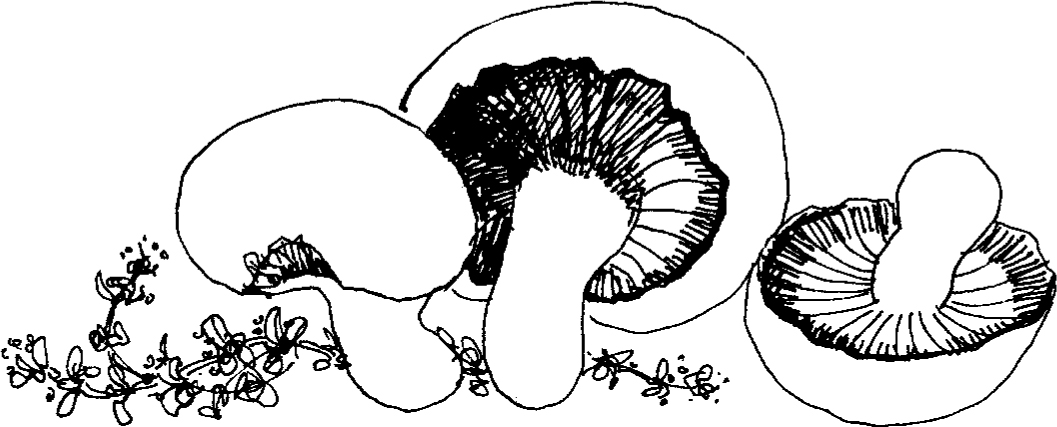

The man who can provide the information on all things to do with exotic fungi is Dougie, Hobart’s mushroom king. Dougie, I am informed by a helpful lady in tourist information, will be able to tell me everything I need to know about the truffle harvest. If I wish to consult him and even take a tour of his mushroom sheds, this can be arranged this very day.

Dougie, summoned to provide information on Tassie’s mushroom production for an important visiting journalist, is willing to oblige. The very picture of a successful Tassie entrepreneur in smart business suit, shirt unbuttoned at the neck to denote a relaxed way of life, Dougie arrives in a brand-new four-wheeler and opens the door with a flourish.

‘Pleased to meet you, lady. Stash the clobber in the back and we’ll take a tour.’

I mention my interest in truffle plantations. To be specific, I add as we speed through the suburbs, the black Périgord truffle, the only one of its genre in successful cultivation.

‘Rubbish,’ says Dougie. ‘Pardon my French, but rubbish.’

Dougie delivers this assessment with such vigour that I decide to leave my questions until later – possibly never.

As we leave the outskirts of Hobart, the four-wheeler swings into a concrete yard and comes to a halt beside a huge and windowless warehouse which could easily swallow a whole forest of truffle oaks.

‘This is it,’ announces Dougie, waving a hand around the concrete battlements. Three more enormous warehouses form the other three sides.

‘Follow me, young lady. You’re going to have an experience you’ll never forget.’

He shoots a heavy iron bolt on the sliding door and stands aside to allow me to enter. The open door releases a cloud of mushroom-scented warmth.

‘Smell that,’ he says, sniffing appreciatively. ‘Pure profit.’

Profit shines moon-white in the darkness, eerie and silent. The scent is fresh and clean and faintly antiseptic.

Light from the open doorway falls on lines of plastic pillows stacked roof-high on slatted shelves.

‘Recycled waste,’ Doug adds, breathing in the aroma. ‘Shit or crap or whatever you call it. Wonderful stuff. The Chinese have been on to it for centuries. Admirable people. Ever been there? No? You should. You’d be amazed by what they can do.’

The door clangs shut behind us and a switch flicks, bathing the stacks in a soft blue light. I follow as Doug strides down the aisles, halting to inspect first one stack and then another.

‘This lot is the white-caps, standard stuff. We pick to order for button, mature or open-cap. Over here, we do the exotics. Oyster, straw, shiitake, the ones the Chinese have been growing for centuries and the rest of us are just catching up on.’

The straw mushrooms are slender little toadstools crammed together on artificial logs in clumps. The chefs love them, but the main market is Japan, though Dougie has yet to achieve the volume for export.

Cropping is monitored electronically, dictating the number of pickers bussed in every morning from the line at the employment office in downtown Hobart, mostly immigrant Chinese on minimum wage.

Dougie has come to a halt at a pile of logs. ‘See these,’ he says, poking at a bundle of what looks like reddish tree-fungi. ‘We’re working on a new variety the chemists have just come up with. We’re calling it beefsteak. It looks and tastes a lot like meat.’

I don’t point out that beefsteak mushrooms have been gathered in the wilds since my ancestors and his were running round the wildwood, painting their faces with woad.

Dougie sighs contentedly. ‘Treat a mushroom right and you know where you are. Not like that other rubbish. Sure it’s romantic. But who gives a recycled excrement for romance?’

Well, Jim, for one.

‘We can do anything we want in here. Anything the chemists come up with, we can grow it. You won’t even know we’ve done it. Remember that next time you pick up a box of what says it is wild woodland mushrooms in the supermarket; don’t think that’s what you’re getting.’

He doesn’t take risks, protects his investment, feeds it, waters it and cares for it, providing everything it needs to make his money grow. Politicians understand the power of money. Money dictates the future. And the future is right here, right now in this glowing mass of man-made nutrients, this precious source of money shimmering in the darkness.

Soon there will be no more need for unskilled labour in the sheds. Everything will be done by robots and profits will soar.

I listen in silence. All at once the warmth of the recycled air feels cold on my skin and I need light and air and sunshine.

Dougie follows me as I head for the door, snapping the heavy padlock in place, leaving his windowless growing-machine to return to silence and darkness.

As we drive back together into Hobart, Dougie is no less certain than Jim about the need to change the world.

‘Our children will thank us for what we’ve done. Hunger will be unknown, our seas will be clean and our landscapes unpolluted. This is the future – we’re too far gone to turn back.’

Dougie may well be right and Jim wrong. When all our food is grown in a man-made circle from production shed to powerhouse to water-pump and back to its own beginnings, our children’s world is saved. Romance is no match for reality. There may well be no room for romance in a world where half go hungry and the rest stuffs itself to bursting, I reflect as I watch the towering cruise-ship discharge a thousand well-fed tourists for the evening’s gastro-entertainment.

Cast the bones, read the runes, consult the oracle. But if the battle is already lost and the inhabitants of this beautiful planet find no further use for the good things of land and sea, the sun will spread its warmth over barren pastures and spill its light into an empty ocean. And our children, yours and mine, will never know the sweetness of a ripe strawberry still warm from its bed, or pluck a cherry from a tree, or taste the soft salt flesh of an oyster fresh from the sea.

A fresh seafood salad made with just-cooked shellfish and crustaceans (except crab, which is not firm enough) is briefly marked on the grill and served warm. Ready-cooked seafood won’t cut the mustard.

Serves 2 as a starter

2 tablespoons olive oil

100 g raw prawns or shrimp, heads on

100 g shucked queen scallops, sliced if large

100 g small squid or cuttlefish, cleaned but left whole

100 g firm-fleshed fish fillets

juice of ½ lemon, plus ½ lemon to serve

pinch of chilli flakes

12 mussels or large clams, in their shells, soaked to de-sand

2 generous handfuls of rocket or other mustardy leaves

sea salt

Preheat a heavy iron griddle pan.

Toss the prawns, scallops, squid or cuttlefish and fish fillets in a little olive oil – just enough to give them a shine. Cook them quickly in batches in the hot pan, allowing only 30 seconds on each side. Transfer to a bowl and dress with a little more olive oil, a squeeze of lemon, a pinch of sea salt and a scattering of chilli flakes.

Meanwhile, cook the shellfish – mussels or clams – either on the griddle pan or in a splash of water over a high heat in a closed pan.

Toss the seafood, including the mussels or clams in the shell, with the rocket, dress with a little more olive oil, heap on 2 plates and serve each portion with a quartered lemon.

MACARONI CHEESE WITH OYSTERS

The oyster’s not much to look at in the hand: a pair of rough-ridged shells clamped tight shut. To prize these apart, you need a strong fist, a thick cloth and a short stubby knife to go in through the hinge. And suddenly there you have it: a mouthful of pearl-grey flesh bathed in salty juices to cook in a cream sauce folded with macaroni and crisped beneath the grill under a crust of parsley, butter and breadcrumbs.

Serves 4–6

8–12 oysters

350 g macaroni or any tubular pasta

salt

For the sauce

75 g unsalted butter

50 g plain flour

600 ml full-cream milk

1 tablespoon double cream

few drops Worcestershire sauce

salt and pepper

2 tablespoons fresh breadcrumbs

1 tablespoon grated Cheddar cheese

1 tablespoon finely chopped parsley

1 large knob unsalted butter

Open the oysters and loosen them from the half-shell, saving the fish and the juice.

Set the macaroni to cook in plenty of boiling salted water for 18–20 minutes – or according to the instructions on the packet – until just tender.

Meanwhile make the sauce. Melt the butter in a heavy-based saucepan. Stir in the flour and let it fry for a moment until it looks sandy – don’t let it take any colour. Allow the pan to cool while you heat the milk in another pan, removing it from the heat just before the milk boils. Whisk the hot milk slowly into the butter and flour, return the pan to a gentle heat and stir with a wooden spoon until the sauce is smooth, no longer tastes of raw flour and coats the back of the spoon. Stir in the reserved oyster juices and the cream. Taste and season with salt, pepper and a shake of Worcestershire sauce.

Preheat the grill to its highest setting.

Drain the macaroni, fold half of the sauce into it and spread it into a large pie dish. Make indentations in the surface with the back of a spoon and drop an oyster into each dip. Top with the remaining sauce, sprinkle with breadcrumbs tossed with the grated cheese and parsley, and dot the surface with butter. Slip the dish under the grill or in a very hot oven to crisp and brown and bubble.

Oatmeal and coconut biscuits baked hard and crisp for ease of transportation were sent to men as iron rations by the wives of Australian soldiers fighting in both world wars. Anzac biscuits are still a popular snack in the bakeries of Tasmania.

Makes 12

100 g plain flour

100 g caster sugar

75 g rolled oats

75 g grated coconut

100 g butter

1 tablespoon golden syrup

½ teaspoon bicarbonate of soda

Preheat the oven to 140ºC/Gas 1.

Combine the flour, sugar, oats and coconut in a large bowl. Melt the butter with the syrup. Dissolve the bicarbonate of soda in 2 tablespoons of boiling water and stir it into the melted butter.

Fold the wet ingredients into the dry to make a softish mixture (you may need more water or oats).

Drop teaspoons of the mixture on to a buttered baking tray. Bake for 30 minutes, until firm and golden.

Transfer to a baking rack to cool. Store in an airtight tin and serve, re-warmed in the oven if they’ve lost their crispness, with a good strong cup of tea.

A buttery cake mixture with a handful of oats for crunch, baked with a layer of cinnamon-dusted apple through the middle – simple but good, particularly with thick clotted cream or a spoonful of home-made strawberry ice cream.

Makes 12

225 g softened butter

225 g soft brown sugar

2 eggs

225 g self-raising flour

2 tablespoons rolled oats

1 tablespoon wheatgerm

2–3 tablespoons milk

For the apple filling

3–4 cooking apples or 4–5 crisp green eating apples, peeled, cored and diced

4 tablespoons soft brown sugar

1 level tablespoon ground cinnamon

Preheat the oven to 180ºC/Gas 4.

Beat the butter and brown sugar together until light and pale, and gradually beat in the eggs. Fold in the flour along with the oats and wheatgerm. At this point the mixture will be quite dry.

Press half the mixture into a Swiss-roll tin. Spread with the diced apple and sprinkle with half the sugar and half the cinnamon. Add enough milk to the remaining cake mixture to make a dropping consistency. Spread this mixture over the apples and sprinkle the top with more cinnamon and sugar.

Bake for 25–30 minutes, until well risen and brown. Cut into a dozen squares and serve warm.

Fist-sized sponge cakes – call them fairy cakes at your peril – covered in chocolate icing and dusted with coconut. Their invention is ascribed to the wife of Baron Lamington, Governor of Queensland when the Queen Empress was on the throne. Lamington fund-raisers are a regular feature of Australia’s charity circuit. The method works best in a food processor and requires all the ingredients to be warmed to the temperature of the blazing Queensland summer before they’re combined for the batter.

Makes 24

4 large eggs, unshelled

250 g self-raising flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

250 g caster sugar

250 g butter, softened

½ teaspoon vanilla extract

1–2 tablespoons milk

For the coating

175 g butter, softened

250 g icing sugar

2 heaped tablespoons cocoa powder

100 g desiccated (shredded) coconut

Preheat the oven to 180°C/Gas 4, and butter and line a rectangular cake tin measuring roughly 25 x 15cm (or equivalent).

Warm the eggs by placing them in a bowl of hot but not boiling water. Wait for exactly 2 minutes and then crack them into a measuring jug. Whisk until thoroughly mixed.

Sift the self-raising flour with the baking powder into the pre-warmed mixing bowl of the food processor and stir in the sugar. Make a well in the middle, drop in the softened butter, half the egg mixture and the vanilla. Beat in the processor for one minute, when the mixture should change to a lighter colour and become thick and creamy. Add the remaining egg mixture and beat for another 30 seconds. Add a tablespoonful or two of milk if the mixture is too stiff to drop easily from the spoon.

If preparing by hand, whisk the eggs in a warm bowl until light and fluffy. Combine the flour with the baking powder and sugar and fold it into the whisked-up egg. Melt the butter and fold it into the mixture with the vanilla extract. Fold in a little milk if the mixture doesn’t drop easily from the spoon.

Spread the cake batter into the tin and level the top with a spatula. Bake for about an hour, until well risen and firm to the finger, testing for doneness with a skewer or a sharp knife – it should come out clean rather than sticky. Leave to cool a little, then tip the cake out on to a rack. When perfectly cool, use a sharp knife to cut the cake into a dozen perfect cubes.

Meanwhile, make the coating. Beat the butter in a warm bowl until really soft. Sift in the icing sugar with the cocoa powder and beat until light and fluffy.

Cover the tops and sides of the sponge cubes with chocolate icing and dust with coconut.