THE DANUBE’S DELTA, ON A RAINY DAY IN EARLY autumn after a long dry summer, is grey and ragged and inhospitable even to the few hardy birdwatchers, myself among them, who take to the canals in rusting paddle-boats in the hope of a glimpse of the wetland’s wealth of waterbirds.

I have a particular interest in the avifauna of the last of Europe’s untamed wildernesses. Before I embarked on a career as a food writer, to supplement an uncertain family income, I provided watercolour paintings of birds of prey – owls, eagles and hawks – to a Cork Street gallery, and the flowering plants of Andalusia for the botanical record at Kew. My preference was always for the avian life of the wetlands – the spoonbills, flamingoes and herons of the marshes of the Coto Doñana when we lived in Andalusia and the children learned their lessons in Spanish, followed by wet weekends under canvas in the Camargue while our children endured a year of French schooling in the uplands of the Languedoc. In mitigation for such arbitrary educational decisions, my own early education was no different – and I had hopes that the intellectual gymnastics required by learning your lessons in three different languages would serve them well in later life. I have no idea if it did or not – unless that none of the three have made the same choices for their own children, my beloved grandchildren.

The Danube rises in the mountains of southern Germany and flows through – or around or along – the borders of Austria, Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania before emptying its waters into the Black Sea by the borders of Russia. Borders are of no importance to the river’s flow. The populations of the towns and cities along her banks are a raggle-taggle mix of people and nations, religiously and culturally diverse. Swabians drifted downriver to tend the vineyards of Hungary; Saxons came from Germany to farm the plains of Transylvania; Turks planted the rice paddies of the Wallachia and established the rose-water industry in the mountains of Serbia.

While the Rhône and the Rhine are accessible from the sea – both are watery highways leading directly into the heart of Europe – the delta of the Danube, though navigable throughout most of its length, is stoppered up at the mouth, serving as a barrier between East and West, protection against invasion from the fierce nomadic horsemen of the steppes of Russia. Perhaps, had her marshlands been more hospitable, the warriors of Genghis Khan, diverted towards the heart of Europe through the malarial plains of Hungary, might have settled along her banks and never gone home.

Centuries later, the armies of the Ottoman Turks ignored the delta, moving northwards to join the river where it broadens to water the orchards and grain fields of Bulgaria and Romania. Their garrisons, marooned in what they considered a gastronomic no-man’s land, taught local cooks how to prepare the sophisticated dishes they ate at home. It was the Turks who taught the subject nations how to wrap the sturdy German dumpling in delicate Ottoman pastry. It was the Ottomans, too, who introduced the gardeners of Bulgaria to the fiery New World chilli. The Bulgarians, the horticulturalists of the Balkans, bred the fieriness out of the chillies and exported their skills upriver to the paprika mills of Hungary. It was also the Ottomans who introduced the botanical riches of the New World to the Old. Within a century or two of their arrival on the quays of Seville, the revolutionary new crops of the Americas, including potatoes, maize, tomatoes, storable beans, marrow, pumpkins, fiery chilli-peppers – fast-growing and tolerant of latitude and climate – had spread throughout Europe, Asia and Africa. And if this seems geographically improbable, consider that an energetic water rat with a sense of adventure could travel from the delta of the Danube to the river’s source in the Black Forest, splash along mossy pathways to the headwaters of the Rhône, follow the river’s flow until the waters spill into the Mediterranean, slip along the northern shores of Africa and paddle home to the Black Sea through the Dardanelles – and all without the need to set furry foot on dry land.

The university of Pécs, founded on the banks of the Danube in southern Hungary in the fourteenth century, continues as best it may to fulfil its original function – the exchange of knowledge between East and West – in spite of the political turbulence endured throughout its history. At the time of my own brief visit, on a sunny Saturday in the autumn of 2013, I saw no evidence of disharmony between the congregations of the city’s handsome baroque cathedral and the worshippers in her beautiful blue-domed mosque – the very reverse, since all were queuing happily for a mid-morning street snack.

Where town and country come together in the marketplace, the instrument for change is the street stalls, where food is prepared fresh to order and sold cheap to traders and their customers. Where there are immigrant or student populations crammed into overcrowded accommodation lacking cooking facilities, little family-run outlets are set up to serve customers yearning for the flavours of home. At first, many of the ingredients have to be imported, until farmers, observing a gap in the market, begin to grow what the newcomers want.

In cities with hungry student populations such as Pécs, the fast food available in the market when the traders pack up for the day is cheap, nourishing and hot. Treats – mostly deep-fried – are often sold from the same stalls later in the day, in the afternoon and early evening.

The street snack drawing a queue on a sunny afternoon in the cathedral square in Pécs goes by the name of kürtőskalåcs. At first sight, what’s on offer looks like a cross between the German doughnut and the Spanish churro: a long thin rope of puffy dough wrapped round a tubular kebab-holder, hollow in the middle and slotted into a metal rod set over a charcoal brazier. Turned slowly, much like the method used to grill Turkish kebabs, the scent that attracts the customers is of vanilla, hot butter and caramelised sugar.

The queue includes students with overstuffed backpacks, churchgoers spilling out from the cathedral after a Saturday concert, and women in headscarfs with children who have just attended prayers in the mosque. Curious as to the method required to produce so unfamiliar a result, I join the line at the counter to watch the culinary process. As far as I can observe from the mixing, rolling and patting, the starting point is a yeast-raised bread dough enriched with egg and butter, much the same as Italy’s festive panettone or Russia’s wedding babka or the kugelhopf, the ring-cake that France’s Austrian-born queen, Marie Antoinette, recommended with blithe unconcern to the angry poor of Paris as a substitute for a baker’s loaf. The method of cooking, however, is distinctly Turkish. This may be coincidence or simply a solution to the problem of street-sellers everywhere – how to attract customers by appealing to eyes, nose and taste-buds.

At one euro for a fistful, it’s irresistible. As for taste, texture and flavour – well, I was as hungry as a woman can be who’s skipped breakfast in favour of a performance of something choral, tuneful and lengthy by the cathedral choir. My purchase is crisp, sweet and pleasantly doughy when dipped into a mugful of Turkish salep – hot milk thickened with powdered orchid-root – ordered at one of the little cafés that ring the main square.

As indeed – I reflect as I settle down with paints and paper on the steps of the war memorial to record the view of the university, cathedral and mosque – are the chips with ketchup available at the ubiquitous fast-food chain just opened for business in the old town hall on the far side of the square, attracting a rival queue, mostly teenagers.

The Danube served as both highway and larder to the people who settled along her banks. The river rises in the mountains of Germany, gathers strength in Austria, spreads itself into malarial marshland in Hungary, tumbles helter-skelter through the ravines of the Carpathians, meets the waters of its mighty tributary, the Sava, just below the fortress of Belgrade, before flowing onwards, broad and deep, through the orchards and wheat fields of Bulgaria and Romania until it turns north towards the Urals and vanishes at the edge of Russia into a vast wilderness of tamarisk, willow and roadbeds.

I met the river first in the early 1980s in Vienna, Budapest and Belgrade, while researching the cookbook I had long planned to write, European Peasant Cookery. And later – always with the joy of renewing old acquaintance – when travelling for similar purpose through Romania and Bulgaria. But it was not until the opportunity arose a couple of years ago to join a week-long river-cruise from Bucharest to Budapest that I had an opportunity to follow the river to her delta.

The delta of the Danube, unlike those of her sister rivers, Rhône and Rhine, remained un-navigable until half a century ago, when a chain of canals was hacked through the reed beds by convict labour from Russia and Romania. Even so, the narrow waterways need constant dredging and are navigable only when the rains have filled the upper reaches of the river to overflowing. The original purpose of the channel-digging was to link Soviet Russia with her satellite nations of the Balkans. Plans included a manufacturing centre to encourage settlement in the salt-mining town of Salinas; the establishment of rice plantations where rice had been grown in Roman times to avoid the need for imported rice from Turkey; and a nuclear power station on the Russian side of the delta at precisely the spot where the earth’s tectonic plates are at their most volatile. Ambitions were abandoned with the fall of Ceaus¸escu and are unlikely to be revived as democracy finds its feet in Romania and Russia is busy elsewhere.

At the point where the river meets the borders of Bulgaria and Romania, it flows steadily eastwards through fields of sunflowers and maize, apricot orchards and vineyards until it finally spreads its waters into the delta at Salinas, capital of the region, once prosperous from the sale of salt but, with the delta’s population reduced to a handful of fishing families, its industrial ambitions now abandoned as a jungle of concrete towers and warehouses.

This year, with the water level in the delta too low for navigation by our river-cruiser, we have been uploaded into buses in Bucharest for the drive through apricot orchards and maize fields until we reach the industrial edge of Salinas. Here some fifty of us brave souls, volunteers in spite of the unpromising weather, are decanted into the drizzle, ready for embarkation on a trio of rusting hulks roped together in the current by the quayside.

‘Dearest ladies and gentlemen, meine Damen und Herren – please to believe that you are most welcome!’

The gloom of the day and the dark bank of cloud waiting to discharge its load over the already sodden marshland has not damped the spirit of Iuliana, our guide to the delta, a sparkling ray of optimism at the end of the visitor season. In the winter, as she has already explained through the intercom on the bus, the marshes are left in peace to the few fishing families whose relationship with the wilderness endures. Iuliana, curvy and pretty with bouncing curls and a technicolour dress sense, sets foot on the first of the rickety gangplanks without a backwards glance.

‘Please all the people to follow me!’

This is easier said than done. The paddle-boats are roped together by wobbly gangplanks, and Iuliana jumps from deck to deck with the confidence of habit. Her charges, a small group of visitors and locals – three elderly British birdwatchers wearing binoculars round their necks, a family from Frankfurt and two young couples from Bucharest – make our way gingerly across the rocking planks holding on to rope handrails until we are all safely aboard the outermost boat.

Iuliana settles herself under the canvas canopy on deck and takes command of the microphone to deliver what turns out to be a trilingual explanation of what we are about to observe.

‘We are commencing our tour of the delta, ladies and gentlemen,’ Iuliana shouts into the crackling sound system. ‘You may sometimes be seeing some fishermen with red hair and long beards who are fishing on the banks sitting in a wooden canoe. The wife has a round face and freckles but you will not see her as she is at home in Salinas looking after the children. If the fisherman fishes some fishes, the family will eat fish soup for dinner.’

The engine cranks into life, the paddle-wheels turn and our transport noses its way out into the sluggish yellow current.

At this moment the rain begins to fall in earnest and everyone but the birdwatchers and Iuliana, plugged into the sound system on deck, disappear below to take refuge from the rain with a restorative coffee in the cabin. The scent of Turkish coffee mingles unappetisingly with the petrol fumes from the engine, softened by the sweet-salt breeze and the grassy scent of the marshes.

This is a wilderness like no other I have ever encountered – more desolate than the wetlands of the Camargue, with their nesting flamingoes, or even, many years ago on a three-month crossing of the desert in the tracks of David Livingstone, the papyrus reed beds of the Okavango patrolled by fish eagles, or, more recently in my travels, the tangled rafts of the Everglades, home to alligators and pelicans.

I take advantage of the abrupt clearing of the decks and the absence of audience to take out my sketchbook, hoping for a glimpse of cranes, egrets, herons, harriers and anything else that has managed to escape the twin hazards of pollution and predation.

Iuliana settles herself on the seat beside me, observing the process of transferring technicolour paint to rain-soaked paper.

‘You are an artist?’

Up to a point, I reply. I earned my living as a botanical and bird painter. But now I write about food and illustrate my own work when I get a chance. And when I travel, this is how I take notes, with images like this – sometimes detailed, sometimes just a reminder of where I am and what I see, but particularly what I eat.

‘This I like very much. My brother is studying art in Bucharest, and he will like to know how you work. So quick.’

At the back of the book is a little sketch of fishermen cooking soup in a pot set on a tripod over a campfire.

‘This is fish soup? What we Romanians call ciorba de peste?’

This, I confirm, is indeed the traditional riverbank cook-up found throughout the full length of the Danube, except that these fishermen are Hungarian and the soup is named for the bogracs, the iron cauldron in which it’s cooked.

‘You are making many such voyages?’

Whenever I can, I answer with a smile. But the sketch was made a few years ago when I was presenting a TV documentary on the paprika industry of Szeged. As demonstration of the excellence of the local industry, the fishermen were happy to cook their famous fish bogracs – the generic name for anything cooked in an iron cauldron over an open fire.

‘This is making a little money for the fishermen from the tourists?’

It is indeed. Szeged’s famous fisherman’s soup is a fixture on the Hungarian tourist trail, promoted by the tourist authority in Budapest.

Iuliana nods. ‘This is good business plan.’

Our conversation terminates abruptly as Iuliana springs into professional mode.

‘Please to look to your left, ladies and gentlemen!’

Right on cue, we pass our first fisherman. He does indeed have red hair and a long beard and is sitting in a boat made out of a scooped-out tree trunk. Iuliana and I wave enthusiastically. The bird watchers are looking the other way.

‘These people are Rus,’ crackles Iuliana over the microphone. ‘These people are Russian Orthodox and we Romanians are Eastern Orthodox.’ She pauses, clicking off the microphone, then resumes. ‘I can tell you that I was attending school with the children of the Rus when my mother was a schoolteacher in the delta. They have lived here for two hundred years because they were not allowed to worship as they wished under the Tsar. I say this because you must not think it was only Stalinists and Communists who oppress the people.’

This is a good joke and Iuliana laughs heartily.

‘These people come here and we don’t mind because they pay their taxes and of course they send their children to school.’

Romania is full of people who are not Romanian, continues our guide. There are Saxons in Sibiu, Hungarians in Timișoara, Slavs in Moldavia, and in Wallachia, by the Bulgarian border on the way to Turkey, there’s a group of Turks who eat Muslim food and keep Ramadan and are perfectly well integrated into Romanian society. Then there are the travelling people, the tsigane. Nobody can do anything about them. When they come to the door, Iuliana’s mother gives them money to go away, and that’s the best anyone can do.

Iuliana switches off the sound system and returns to settle back beside me.

‘You have many of these books at home?’

Indeed I do, hundreds. And I carry spares whenever I travel, some of which have sketches from previous visits.

‘If you don’t mind, please can I see?’

I hand over a nearly finished sketchbook carried for just such a reason, as a way of establishing common interest in how other people live and cook.

Iuliana flips through the pages with delight.

‘Hah! I think that this is milking of sheep in our mountains of Carpathia? Am I right? And here we are again in Sibiu – this is how they build their houses and here is the big church with the clock. Sibiu is where my father’s family lives. Did you taste their sarmale, the little rolls of rice and meat in cabbage leaf? This is what we prepare for weddings and other parties. In Moldavia they like their sarmale small enough to be eaten in a single mouthful. In Sighișoara they like them big enough for two bites, which is how my sister likes them. Her husband is from Moldavia, so every time they want to have a party, they have a fight.’

And Iuliana herself, how does she like her sarmale?

‘Myself? I like them how my mother makes them in Timișoara, which is just right. You know the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, which was the first book in English that I am reading? My mother makes sarmale just right, like the porridge of the middle bear, which is how she will make the sarmale when I am married, though I have not yet chosen a husband.’

Does she have anyone special in mind?

Iuliana laughs and shakes her head. ‘Perhaps I will find myself a nice polite Englishman who wears a bowler hat and carries an umbrella. You never know. Do you have a picture of a good husband for me in your book?’

I admit to a lack of nice polite Englishmen in my sketchbook. Fishermen maybe. And shepherds milking sheep. But none of these seem to fit the bill.

‘You are right!’

Iuliana’s peels of laughter send a pair of elegant little waders – redshanks by the look of their bright-orange bills and scarlet legs – skimming away across the water. I return to my sketchbook. When a bird is on the wing, the trick is to hold the image in the eye for long enough to put paint on paper.

Iuliana watches with interest.

‘So quick. You always work like this?’

Fast and rough? Yes indeed. It’s the only way to make sure I get what I need. Even though the images catch just one particular moment, the sketches tell me far more than the hundreds of images captured on a camera.

Better still, I add, sometimes they allow me to make a friend like Iuliana who can help me understand what I see.

Iuliana frowns.

‘I can tell you what you are seeing right now, right here in the delta. There are no more fishes. Maybe some little fish for soup, but the big fish, salmon and sturgeon, the caviar-fish that could be sold for money, is gone. What good is soup-fish to a fisherman who has to pay bills for his family?’

So what will happen if the big fish never return?

Iuliana shrugs. ‘The fishermen sometimes catch a little one, but they are too young to make caviar. The caviar-fish takes many years to make eggs, so the fishermen in the marshes will have to find other ways to earn a living. They don’t want to go back to Russia where they come from, and they don’t want to live anywhere else because that is their home.’

Iuliana pauses, then resumes. ‘I am not Rus but I too am from the delta. My mother was a schoolteacher in a village until the school closed because there were too few pupils, and now she lives in Bucharest. But still she makes the best fisherman’s ciorba, even though she has to buy the fishes in the market instead of waiting for my father to come home from the river, like your fishermen in the picture.’

She sighs. ‘All this talk of ciorba is making me hungry. I wish I had some now.’

Ciorba, the Turkish name for soup, Iuliana continues, is one of the culinary legacies of five centuries under the Ottomans who ruled all of Romania. Perhaps, she adds thoughtfully, the connection is marketable – they had a reputation for the delicious things they ate. The garrisons of the Turks brought coffee and sugar and pastries perfumed with rose water, and taught their cooks how to prepare the good things they liked. And sarmale, of course, which are also made with vine leaves in summer and cabbage in winter. You can tell where you are in Romania – or Greece or Bulgaria or Serbia or anywhere in the Balkans – just by asking people how they like to prepare their sarmale.

This opinion having been delivered and digested, Iuliana walks over to the rail where the birdwatchers are sweeping the banks with binoculars. A rarity has been spotted. A gang of four squaccos – smallest and prettiest of the heron family, with pinkish-purple backs and black-spotted golden crests – are examining the current for signs of prey from a perch on an overhanging branch.

Iuliana is not impressed by the diminutive fishermen.

‘These birds are eating many fishes.’

When I take up my brush and make a few strokes, Iuliana shakes her head in disapproval. ‘I do not like these birds.’

There are not enough fish in the delta to support the human fishermen who remain, and fishing-birds – of which there are, in Iuliana’s opinion, too many – represent the competition.

The birds whose diet is under scrutiny are members of the last remaining breeding colonies in all of Europe. I have observed them before in the Camargue in southern France and in the delta of the Guadalquivir in Spain, where their presence is always a delight. Sociable little fellows, squaccos nest in mixed heronries with their larger relatives, storks, spoonbills and egrets. When their nesting companions disappear, so do the squaccos, and the sight of four in a row on a branch are, the birdwatchers and I agree, worthy of a tick on anyone’s ornithological life list.

‘We have very many of these in the delta,’ says Iuliana dismissively. If fish stocks continue to be depleted, soon even the Rus would not be able to survive in the delta. No one else would put up with the rain, the mosquitoes and the general discomfort of life in the marshes. And then there would be no red-bearded fishermen to entertain the tourists, could anyone ever persuade them to do so. Even if not and the fishermen preferred to keep to themselves, the marshes would be all the poorer for their absence.

And in that case, Iuliana’s newly formulated plans for marketing fishermen’s fish soup as a tourist draw would be dead in the water, just like the sturgeon and the salmon and the birds and everything else that made the delta a pleasure for visitors and might, in time, be an opportunity to restore the delta to its former glory.

With the refugees in the cabin showing no signs of braving the elements and the birdwatchers contented with ticking their lists, Iuliana returns to musings on her childhood and that of her family before her. Life was better in the delta in her grandfather’s day, when there was a living to be made in the marshes. In her grandfather’s day, even in Iuliana’s own childhood, there were birds and animals everywhere, the river was full of fish and the delta was populated with Turks and Ukrainians as well as Romanians and Rus. It was safe, too. Strangers and thieves didn’t venture into the wilderness at night for fear of wolves and bears. Not that there were many of those left by the time the Russians went home, but the villagers encouraged the rumours.

By now we are proceeding at a steady pace through the mist and rain, sliding between chocolate-coloured banks on coffee-coloured water. In some places the bank has collapsed into the river, uncovering gigantic bare roots among which the white feathers of egrets shine like snow. A heron stands motionless at the edge of the water, one-legged and crook-necked, searching his mirrored reflection for prey.

‘These birds are also eating too many fishes,’ says Iuliana, switching on the microphone to alert the audience below as a marsh-harrier slips into view and disappears downriver. A flotilla of black and white guillemots rises untidily from the shallows and hurtles away, skimming low to the water.

‘See everyone, is kingfisher!’ shouts Iuliana, waving at a capsized tree.

Three pairs of binoculars – and my paintbrush – swing as one, catching a flash of metallic blue. The bird drops like a tiny torpedo into the water, emerges with a sliver of silver in its gunmetal beak and vanishes into the reed beds.

‘Kingfisher is very nice bird. Very pretty,’ says Iuliana approvingly. ‘This bird is taking only small fishes and baby frogs, tadpoles, and there are many of these so we do not mind.’

Iuliana clicks off the microphone and returns to reminiscence. Even when she was a child, the river was full of the sturgeon, enormous fish with plenty of roe. In those days, the Russians came over the border to buy the caviar for roubles, some from as far away as Moscow.

Sturgeon makes good ciorba. The Rus made good ciorba with sturgeon, but theirs was never as good as her mother’s.

‘My mother’s ciorba is made by putting plenty of bony little soup-fish in a big pot with water and not too much salt and boiling it up till the broth is strong. Then the small fish are taken out with a sieve and potatoes, and if you have big fish, this is cut in pieces and added to the broth. If there are no big fish, you add more potatoes. And since a ciorba must be a little sour, you must add a little vinegar.’

The vinegar, she continues, is not necessary if the cooking liquid is bors. This is not, as the name suggests, the Romanian version of Russia’s beetroot and cabbage soup, but a cooking broth made in much the same way as kvass, by fermenting a handful of bran in water with a little yeast.

I lay aside my sketchbook and concentrate on her story. Perhaps it is possible that a fish soup, ciorba de peste, might be available in Salinas today? According to the guidebook, this is market day, and there might be one or two of the little restaurants that cater to market traders and their customers after the day’s deals are done.

‘Market is not in schedule,’ says Iuliana decisively. Then, softening, ‘But I will see what I can do for you in Bucharesti.’

She busies herself on the mobile phone as our transport returns to the quayside, the Germans and Romanians emerge from the cabin, and the ornithologists pack up their manuals and binoculars. Once we are all safely stowed in our seats on the bus ready for the return journey to Bucharest, Iuliana comes to find me at my seat.

‘It is all arranged. You will meet with my cousin Codruta at the café at the British Council tomorrow at coffee-time. She works in the library there and teaches a class in English. I think you will like each other. She too is interested in the things that interest you – food and history – and she has a brother who is a chef in a restaurant.’

Romania and France have always had much in common, culturally and gastronomically. In the old days under the monarchy, Bucharest’s French restaurants were famous as far away as Paris, and French was the language of the intellectuals of Bucharest before the Russians took over. French pâtisseries were the first to reopen for business after the fall of the regime, to provide the citizens of Bucharest with the delicate cream-stuffed cakes and pastries they loved and had never forgotten.

The dictatorship was a terrible time for anyone who remembered the regional diversity of the old days. Under Ceaușescu, all Romanians had to eat the same food prepared to recipes provided by the state. Never mind about the cooking of the Saxons, Hungarians, Turks and Slavs, everyone had to eat the same food cooked according to the official cookbook – so many grams of meat, so many grams of potato, so many grams of salt. All food supplies were the property of the state and were diverted to schools and workers’ canteens. If you didn’t work or go to school, you didn’t eat. And to ensure no backsliding, all non-official cookbooks had to be turned in to the police station and burned in public in town squares. Naturally enough, the nation’s grandmothers hid their household manuals under the mattress until the dictatorship collapsed and life returned to normal – more or less.

These days, twenty-five years after the fall of the regime, Bucharest has restored itself to elegance and Frenchness. Gap has opened outlets in suburban shopping malls. Prada handbags, Louboutin heels and Hermès scarves are on sale in the smart boutiques of the capital. Nevertheless, the city is still in a state of permanent makeover. The main square is heaped with rubble, the result of repairs to the sewer system, as it was under Ceaușescu, when the joke doing the rounds was that the reason for the excavations was that the murderous old dictator was trying to find his mother. Romanians have a dry sense of humour that served them well under Communism.

Research, for me, starts in the pages of Victorian and Edwardian travel writers, some of whom – mostly women – recorded what their hosts put in their mouths. Thereafter, for me, it’s a matter of a willingness to talk to strangers encountered in places where natives as well as foreigners take refreshment. I usually settle down in a corner and paint. Sketchbooks and paint box are invaluable tools in opening up a channel of mutual interest.

Codruta comes to find me in the café attached to her offices. She is a history graduate, slender, pretty, dark-haired and earnest, employed by the British Council to catalogue the library and teach English classes to Romanians who wish to learn the language.

After preliminary introductions and talk of her cousin and her work as a guide to the delta, we turn to the main purpose of our encounter: the family’s traditional Sunday lunch, ciorba with meatballs. It is not possible to invite me to the family home, since they live a hundred miles away in Timișoara on the Hungarian border, but if I wish to experience an approximation of the real thing, Codruta will be happy to accompany me to lunch at the Hotel Phoenician, where her brother is the under-chef and can be relied upon to cook a ciorba de chiftea according to the family recipe.

The Phoenician, a vast new hotel built of concrete, steel and glass for Russian apparatchiks in the Communist era, is marooned in the outskirts of a shopping mall. The dining room has a festive air, with tables draped in shiny green damask and gilt table-settings among which a group of smartly suited dignitaries have already settled down to enjoy their platefuls.

Codruta advances purposefully towards the buffet, a magnificent self-service display in the next room, and searches through the bowls of cream-dressed salads, breaded chicken and chips in tomato sauce – ‘peasant potatoes’ says the helpful little label – until she finally lifts the lid of an ornate silver tureen.

‘This is just what I have asked of my brother,’ she says, inhaling the steam. ‘This is ciorba prepared with bors, very traditional, very correct.’

Ladling out two steaming bowlfuls, releasing a yeasty, mushroomy fragrance, she tops each portion with a spoonful of soured cream.

‘You must eat it like this, with apple-chilli.’

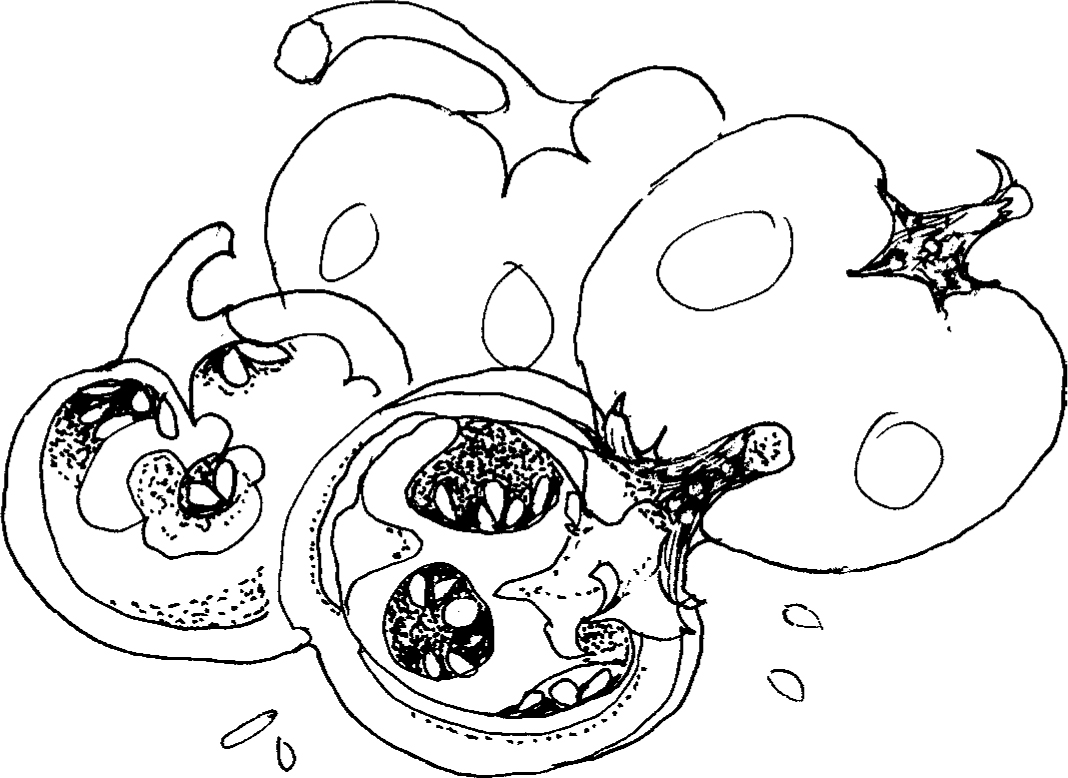

Apple-chilli, a small round capsicum, bright red and of a size to fit snugly in the palm, does indeed look like the roundest and rosiest of apples.

Codruta takes a mouthful of soup and a bite of chilli, and nods approvingly. ‘First you take some soup, then some chilli, then soup again. Apple-chilli is not so very hot, very juicy, very sweet, very good for stomach.’

I follow her example as soon as we settle down at a table. The famous soup is a clear straw-coloured broth with a pleasant rather beery sourness, in which have been poached tiny bite-sized meatballs speckled with grains of rice and something green and scented which my taste-buds tell me is lovage, a peppery relative of the celery family that grows enthusiastically in my garden in the Welsh uplands. The flavour of lovage is stronger and ranker than celery – though I sometimes include it sparingly in vegetable soups – but the sharpness of the broth and the delicate flavour of the meatballs suit it to perfection.

‘Delicious,’ I say, as I mop up the last drops from the bowl.

Codruta smiles. ‘I shall be happy to tell my brother of your appreciation.’

I should understand, she continues, that the method of souring a ciorba is important. If vinegar is used, the soup is Bulgarian, even though Romanians use it too. If lemon juice is used, it’s Greek. If the souring agent is sumac – a powder prepared from sour little fruits of a shrub endemic to the southern shores of the Mediterranean – it’s Turkish. If the sour flavour comes from bors, as now, it is Romanian or Russian or Turkish, where it is used to add depth to a cooking broth as one might add wine.

Since bors takes several days to prepare, it is possible, she adds, to buy it as a soup-cube. And when the cook is in a hurry, as her brother is today, a soup-cube is perfectly acceptable.

I agree that the ciorba is delicious, in spite of the soup-cube, and would be happy to be able to congratulate the chef in person. Unfortunately this is not possible owing to Romania’s strict interpretation of rules governing hygiene in commercial kitchens.

‘This comes from the time of the dictatorship,’ Codruta adds. ‘At that time, you must understand, everyone had to take their midday meal at their place of work – schools as well as factories – in government canteens. At that time the marketplaces were closed, government supermarkets were the only places you could buy food, and people were forbidden to cook at home. But Romanians don’t always do what we’re told, and people went on growing food in little patches of earth hidden behind the houses and carried on preparing the dishes they liked to eat according to who they were.’

Codruta glances around to see if we are overheard, then continues, ‘One day the government decided the people were disobeying orders to eat only Communist food prepared according to the government manual. They were still cooking Romanian ciorba or Hungarian goulash or Saxon dishes prepared with sausage and sauerkraut and all the other dishes that remind people who they are and where they belong.’

She pauses, smiling at me. ‘Can you possibly imagine what it would be like if English people were forbidden to eat shepherd’s pie, or roast beef with Yorkshire pudding? If you do, you will understand how angry it made the people. But we couldn’t protest because the secret police were everywhere. So when everyone was told to bring their household books to the police station – the handwritten ones that were like the family Bible – we did as we were told.’

‘That must have been hard.’

‘It was. Even though I was just a little girl, I knew how much pain it caused my mother and grandmother when the police made a big bonfire of all the books in the market square and the children were taken to watch. But what I didn’t know was that everyone gave the police a book that didn’t matter and hid the real one under the mattress. So when the revolution came and the dictatorship ended and the markets were open again, there was food to set on the table and everyone brought the books out from under the mattress and nothing was lost.’

She frowns, then lifts her head and smiles. ‘Perhaps, as a mother and grandmother yourself, you would have done the same?’

I hold out my hand to take hers. I feel it every time, I reply, whenever my own children or grandchildren are gathered together under my roof. The dishes that speak to the heart are those we remember from childhood, that remind us who we are and where we come from.

Codruta nods. ‘I hope you will not forget the meal we have shared today when you return home to your own country. There are many opportunities for friendship and understanding between the nations of Europe, and for that we have reason to be thankful.’

Another pause. Then, slowly: ‘This is why this dish we have shared today is so important to us, and why it should never be forgotten.’

CIORBA DE PESTE (FRESHWATER FISH SOUP)

A simple soup prepared using the Danube’s bony young river fish: pike, tench, roach, bream, catfish, carp, small sturgeon, whatever swims into the net. Save any larger fillets to poach in the broth at the end.

Serves 4–6

2 kg small river fish

1 kg onions, peeled and finely chopped

1 kg potatoes, scrubbed and sliced

1–2 tablespoons vinegar or lemon juice

salt

To serve

fresh red chillies

1–2 tablespoons hot paprika or chilli powder

Rinse and gut the fish but leave the heads on and do not scale. Remove and reserve any meaty little fillets.

Pack the small fish into a large saucepan with about 2 litres water and a teaspoon of salt. Bring to the boil, turn down the heat and simmer uncovered for 50–60 minutes until the fish is absolutely mushy.

Strain the broth through a sieve or mouli, pushing through all the little threads of flesh but leaving the bones behind. Return the broth to the pan and add the chopped onions and potato slices. Bring to the boil, turn down the heat and simmer gently for another 20–30 minutes until the vegetables are perfectly tender.

Taste and add salt – river fish have no natural salt, so extra salting is usually necessary. Stir in the vinegar or lemon juice, just enough to add savour. If you have any reserved fish fillets, slip them into the boiling broth just before serving.

Serve ladled into bowls with chopped chilli on the side. If using dried chill or paprika, stir it with a ladleful of the hot broth and hand round separately.

Bors, a mildly fermented wheat-bran beer, is used for sharpness and flavour in a ciorba (‘sour’ soup), much like wine in grape-growing regions. You can find commercially prepared bors sold in concentrated form as a soup-base in Polish, Russian and Turkish delis as well as in Romania. The flavour is surprisingly mushroomy, umami-laden, with a touch of sweetness and just a little sourness, as if someone had added a glass of sharp white wine.

Makes 2 litres

250 g wheat bran

1 hazelnut-sized piece fresh yeast or 1 teaspoon instant yeast

2 tablespoons cornmeal

2 litres spring water

Start 3–4 days ahead. Combine 2 tablespoons wheat bran with a cupful of warm water and add the yeast. Leave to froth for a couple of hours, then drain and reserve the bran, discarding the liquid. Put the remaining dry bran in a clean bowl with the cornmeal. Boil the water and pour it into the bowl. Mix and leave to cool to body temperature, then stir in the yeasty bran.

Cover with a clean cloth and set aside for 3–4 days in a cool place, stirring regularly, until delicately soured. Strain into a clean glass jar, store in the refrigerator and use as required.

To start another batch without yeast, reserve a cupful of the strained bran and proceed as above, adding the yeasted bran to the new batch at the stage when the bran-and-water mixture has cooled to body temperature.

CIORBA DE CHIFTEA (SOUR SOUP WITH MEATBALLS)

Tiny meatballs poached in a clear broth soured with bors – wheat-bran beer – this is a party dish to be eaten with a generous dollop of soured cream and a bite of apple-chilli.

Serves 4–6

For the meatballs

350 g finely ground beef, lamb or pork

2 heaped tablespoons (uncooked) risotto or pilau rice

1 small onion, peeled and grated

1 egg, beaten

1 generous handful of chopped dill or fennel tops

1 generous handful of chopped parsley

For the broth

600 ml chicken or beef-bone broth

600 ml wheat-bran bors, or water and white wine plus 2 tablespoons wine vinegar

1 heaped tablespoon shredded lovage or celery leaves

soured cream

fresh red chillies

Work the ground meat with the uncooked rice grains, onion, egg, half the dill and half the parsley until well blended and smooth. Roll into balls about the size of a walnut.

Bring the broth to a boil, gently slip in the meatballs, return the pot to the boil, turn down the heat and leave to simmer without bubbling for 30–40 minutes, until the meatballs are tender and the rice is cooked through.

Strain the bors into the broth (or add the wine, water and vinegar) and reheat to boiling point for a couple of minutes.

Finish with the shredded lovage and the rest of the parsley and dill. Ladle into bowls and add a dollop of soured cream. Serve the fresh red chillies separately, one for each person.

SARMALE (STUFFED CABBAGE ROLLS)

Sarmale is the generic name throughout the Balkans for little rolls of leaves – cabbage or vine – filled with rice and meat known as dolmades to the Greeks and dolmasi to the Turks. The wrappers are preserved under salt for the winter and the sizes of the rolls vary according to size of leaf and regional preference, as do the flavouring ingredients. Iuliana’s mother’s recipe includes tomato in the stuffing and is sauced with soured cream.

Serves 6–8

1 large green cabbage

2 carrots, scraped and finely chopped

2 sticks celery, finely chopped

4 tablespoons seed oil (sunflower or pumpkin)

1 medium onion, peeled and finely chopped

2–3 garlic cloves, peeled and chopped

250 g risotto or pilau rice

1 large ripe tomato, skinned, de-seeded and diced

1 tablespoon finely chopped dill

1 egg, lightly beaten (optional)

salt and pepper

To finish

300 ml soured cream

Trim the base of the cabbage and place the whole head in a large bowl. Pour in a kettleful of boiling water and leave it just long enough to soften the bases of the leaves, then drain. Remove about 18 of the large outer leaves and lay them flat, ready for stuffing, pressing down with the flat of your hand. Cut out the hard stalk and discard, shred the remaining inner leaves and put them in a large casserole with the carrot and celery.

Heat the oil in a frying pan and fry the chopped onion and garlic until soft and golden – don’t let it brown. Add the rice and stir it over the heat until the grains turn translucent. Season and add enough water just to submerge the grains. Bring to the boil, turn down the heat and simmer for 10 minutes, when the grains will be chewy but most of the water will have been absorbed. Tip the contents of the pan into a bowl. Work in the tomato, dill and egg thoroughly with your hand, squeezing to make a firm mixture.

Drop a tablespoonful of filling on the stalk-end of each leaf, tuck the sides over to enclose, roll up neatly and transfer to the bed of cabbage in the casserole. Continue until all the mixture is used up. Add enough water to cover the stuffed leaves, bring to the boil, turn down the heat, cover with a lid and simmer gently for about an hour, until nearly all the liquid has been absorbed. Spoon the soured cream over the top and serve warm.