THE FRAGRANCE THAT FLOATS ACROSS THE SHIMMERING acres of salt flats on the breeze in the Little Rann of Kutch is unmistakable.

‘These people are harvesting cumin, my lady.’

The speaker, Devidas, employee of the tourist board in Ahmedabad, capital of the north-western region of India, is charged with accompanying me, as a visiting journalist, to places that, in Devidas’s opinion, no sane person would wish to visit.

The Little Rann and the Great Rann of Kutch do not feature prominently on the list of India’s popular destinations for Western tourists – in spite of the rarity of the last remaining herds of wild Asiatic asses and the last of the Asiatic lions – but they are most certainly on mine.

For the first two days of our association, Devidas, rightly in his view, sees it as his responsibility to deliver the usual itinerary of temple-visiting and admiration of architectural splendours. I, on the other hand, wish for wilderness, markets and people.

‘I question the wisdom of this choice, my lady.’

I have already given up trying to convince Devidas that I have no claims to ladyship of any kind, inherited or earned. And since Devidas speaks very fast and supple Indian English, I am not always able to catch the subtleties of his drift.

Today I have had my way, and Devidas has agreed to inspection of the salt flats of the Little Rann in the company of Muzaid of Rann Riders, a new enterprise offering nature-lovers and birdwatchers accommodation in luxurious wattle-and-daub cabins modelled on the safari camps of South Africa.

Gujarat’s two great wildernesses, the tourist board decides, are suitable for development as luxury destinations for nature-lovers in much the same way as the safari parks of Africa present their game reserves. This decision is responsible for my presence with notebook and sketchbook on the salt flats of the Little Rann on behalf of the readers of Food and Travel.

Muzaid, as manager and part-owner of Rann Riders, has driven over from his home in Dasida, the nearest town, to open up the camp and provide overnight luxury accommodation unavailable elsewhere. Muzaid has also been at pains to point out, as he gives me a brief tour of the facilities, that it is his cousin the Rajah who actually owns the camp. This is not to say that this particular Rajah is one of your palace-dwelling Moguls of the type you find in Rajasthan, but a working citizen of the egalitarian state of Gujarat, doing the best he can for his family in the India of today.

‘This is how we are in India – hierarchical, given that there’s always an obligation to look after family – which is why it is myself rather than my royal cousin who is privileged to enjoy the beauty of this place and the pleasure of excellent company such as yours.’

Muzaid is charming, handsome and very much a son of the Mogul Empire, followers of the Prophet who ruled Hindu India for three hundred years before losing out to the garrisons of the Queen Empress.

Devidas, on the other hand, is a modern citizen of urban India, distrustful of the countryside, with a little too much good living under his belt, teetotal and vegetarian even though his favourite fast food is breaded chicken nuggets from Chicken Shack in Ahmedabad.

The two men are not destined, it seems to me, to be soul mates.

The salt-cured cumin of the Little Rann is harvested at the end of the dry season, just before the monsoon rains fall, as they do in roughly one year in three. The breeze from the salt flats blows through the ripening seed-heads when the salt dries out the pans to form a thick crust, which is raked by hand into glistening pyramids of crystallised salt.

Proximity to the salt flats delivers cumin of unusually high quality, esteemed for strength, fragrance, resistance to insects and an almost indefinite shelf life. In flavour and scent, this diminutive pink-flowered member of the aniseed family is unmistakable. A sunny blend of liquorice, cinnamon and clove, it is the fragrance that rises from every kitchen in India as well as throughout the Arabian peninsula and much of the Middle East.

Used medicinally, cumin encourages appetite and aids digestion. It is the basic flavouring for garam masala, the spice mix used to perfume everything from the sophisticated sauces and stews of the Mogul kitchen to the simplest dish of dhal and chapatti, the daily dinner of the poor and those who choose to live in simplicity. It’s also the flavouring in chai, India’s milk-based tea, sold from roadside stalls to the millions of travellers and pilgrims who wander the length and breadth of the land on foot.

Little else can be found in the Little Rann that’s useful to man or his domestic animals apart from the salt and ragged clumps of grass that serve as fodder for scattered herds of the last of the wild Asiatic asses. A dozen or so of the handsome little beasts, their coats a dusty pink picked up from the parched red earth of the desert, are grazing on new growth along the edge of what looks like a dried-up riverbed.

Survival, I say to Muzaid, seems a miracle in such a desolate landscape.

The river wasn’t always dry. When Muzaid was a boy the river never ran dry unless the rains failed for many years in a row. But now that the river has been taken further up the flow to irrigate farmland and supply water to the cities, the government pays money to the villagers to dig waterholes for the asses and satisfy the conservationists.

‘Conservation is a political issue in India. However much we’re told by you in the West to preserve our tigers in spite of the villagers they kill, it’s only when we ourselves decide we don’t want to lose what we have that our politicians take notice.’

The only commercial crop available from the Little Rann consists of vast deposits of sea salt, tip-tilted by the ocean when the earth’s tectonic plates clashed together to form the Himalayas. The care of the salt flats and the raking and drying is the ancestral right of a single family living in ramshackle huts by the pans for six months at a time, rotating their tour of duty with fellow family members.

‘The work is hard and the pay is low but the labour is hereditary – and that counts for much even in the India of today. Perhaps it could be compared with your miners who couldn’t bear to leave the coalmines whatever the dangers and wanted their children to work as they did.’

Today in the last of the summer sunshine, the cumin is ready for harvesting. Brightly dressed women and children working in pairs are tossing forkfuls of golden seed-heads high in the air with wooden pitchforks, separating the grain from the chaff as it falls in a glittering arc into shallow woven baskets. The scent carried towards us on the breeze is of new-mown hay, fresh and sweet and dry. The winnowers work together in silence, keeping the rhythm, bending and swaying like dancers. Meanwhile their menfolk, reed-thin in loincloths and heavy boots, are raking a thick crust of snow-white salt from the mud-rimmed pans into shimmering heaps of crystals.

‘These people are tribals,’ Devidas announces with confidence. ‘Tribal is what we in India call people who live traditionally because the other word is not polite.’ There are many such linguistic pitfalls to trip up the unwary as India rids itself of its socially divisive caste system. We both know that the other word is ‘untouchables’, an outdated caste to which no one belongs.

Devidas, born and bred in Gujarat’s densely populated capital, has a town-dweller’s distrust of inhospitable places. Surely by now, two days into our trip, I would agree there was no need to leave the city at all? There are so many pleasures available in Ahmedabad that there can surely be no need to travel elsewhere.

‘All in due course, Devidas,’ I answer soothingly, flicking paint on to paper.

Devidas heaves a sigh of resignation, and borrows my bird-watcher’s binoculars to inspect the group of harvesters and deliver his verdict on their activities.

‘These people are throwing the cumin up in the air and catching it in baskets.’

Meanwhile, Muzaid has already swung long khaki-clad legs out of the vehicle and is striding purposefully towards the harvesters. It’s clear from the enthusiasm of the greeting that the relationship is warm.

In the old days, Muzaid admits when he returns to rejoin his passengers, the arrangement was undeniably feudal. But there was mutual respect, and even as India changes, respect remains and the relationship continues. As middleman for the sale of the harvest, Muzaid makes sure the crop fetches good prices in the marketplace and that the villagers benefit from the income derived from the tourists who come to spend their holiday dollars with Rann Riders.

The rains came early this year and the cumin is plentiful and well ripened and will fetch a good price.

‘Taste this – see what you think.’

In Muzaid’s outstretched palm is a little heap of greeny-yellow grains. I set down my sketchbook, accept a pinch and rub the grains between my fingers, releasing the fragrance. The scent is fresh and grassy, but the flavour, when tasted, is peppery and rank, unfinished, as if the raw material is not yet cooked.

‘What’s missing?’

Muzaid smiles. ‘You’re right. I’m used to eating them fresh – it’s the taste of my childhood.’ The final stage is yet to come, he continues, when the seeds are spread in the baskets and left to dry in the sun, a slow process compared to what happens when cumin is prepared commercially. The cumin of the Little Rann is sought after not only for its excellence but also its rarity, since only a few bushels are harvested every year.

‘We Gujaratis love to trade; we’re always looking for the best price in the best place. It’s in the blood. When I came home from boarding school in England for the holidays, my father took me to the marketplace every evening to listen to the dealers talking about where they went and the deals they did. Their stories were magic.’

Gujarat’s merchants travelled east along the Silk Road, through the passes of Afghanistan and west to the shores of the Mediterranean and into Africa. Gujaratis were trading with Portugal well before Marco Polo found his way to China. Cumin from Gujarat was used to perfume dishes served to the diners of imperial Rome.

These reminiscences are interrupted when the vehicle rolls to a halt beside an untidy clump of dried-out plant stalks just before we turn into the campsite.

Muzaid reaches through the wound-down window and snaps off one of the stalks. It is thick-walled and hollow and the scent of aniseed is unmistakable.

‘When I was a boy, my father used a hollow stalk like this to carry hot coals to light the campfire when we were hunting in the desert.’

In a moment, he is out of the vehicle and scraping the earth around the root of the clump with a hunting knife. A slash of the blade produces a trickle of milky sap.

‘It’s what we call hing – asafoetida. I don’t like it myself, but I am Muslim and this is used in Hindu cooking to give the flavour of onion. If you ask me, onion is better.’

‘This is not exactly so, my lady,’ Devidas remarks without raising his voice above a whisper. ‘But because Mr Muzaid is our host and courtesy is due, we will not quarrel when the milk is already spilt.’

This evening, for my further instruction in the ways of Gujarat’s countryside – though possibly because the kitchen’s closed – Muzaid has arranged for us to take our evening meal in one of the scattered communities of Rabari, desert nomads who settled the Little Rann many centuries ago and still live much as their ancestors did, keeping goats and gathering foodstuffs from the wild.

‘Perhaps so, but I am presenting my excuses, my lady,’ says Devidas.

Muzaid ignores this negative appraisal. Rabari cooking is of particular interest for its inclusion of herbs and berries as flavourings that even one who has lived here all their life cannot identify for certain.

Devidas remains unimpressed. ‘These people eat only roti and dhal.’

We must arrive at the village after sundown, Muzaid continues, which is when the fires are lit and the pots are set to simmer in the communal cooking area.

‘This, my lady, is because these people have no toilet facilities inside their houses but must do their business without privacy where they do not like people to watch,’ says Devidas. And anyway, it is his duty to check the itinerary with head office and make sure everything is ready for tomorrow’s departure for an even bigger and more desolate region, the Great Rann of Kutch.

It’s as plain as the nose on his face that Devidas is not an admirer of deserts and those who dwell therein. I, on the other hand, am delighted with our day in the salt pans with the cumin-harvesters and even more so with the prospect of an informative evening and the company of my courteous host.

On the way to the village as the sun dips towards the horizon, Muzaid pulls into the side of the track and trains his binoculars on a reed-fringed pond. A raft of waterbirds – mostly mallard and garganey – are drifting tranquilly on the dark surface. To me, this is an extraordinary sight in a desert region, but Muzaid is unimpressed by the gathering.

While the main draw for nature-lovers in the Little Rann is the wild asses in the breeding season, in a good year, when the rains have filled the reed-fringed pools from the edge of the desert, the wilderness provides a haven for nesting birds. Rosy-feathered flamingoes migrate from the deserts of Africa to build their drip-nests from the red earth turned to mud by the monsoon rains. Egypt’s sacred ibises and China’s demoiselle cranes take up residence among the reed beds to feast on hatches of tadpoles and frogs.

‘Such a pity we’ve just missed the crowd. I was hoping the ibises and flamingoes would still be rearing their young. My ancestors used to hunt them with golden eagles. Eagles are fearless hunters – I once saw one attack a wolf.’

‘Who won?’

Muzaid considers the question with a smile. ‘Let’s just say that both held retreat to be the better part of valour, as your Mr Kipling says. I wish our politicians would do the same.’

Muzaid is in thoughtful mood as we rattle along the dusty track, bouncing in and out of the ruts. There are divisions between Muslim and Hindu opening throughout India once again. There is no solution to an intractable problem. If Pakistan is Muslim and India is Hindu and no one wants to be the first to offer compromise, sooner or later war is inevitable. Meanwhile, Gujarat is a frontier region, as it has always been, with friends and family on both sides of the border.

‘Perhaps you will see this in the Great Rann, when you travel there tomorrow, or perhaps not. My father always told me there’s no place safer in all the world than a hundred miles behind a warzone. And trouble never starts in the countryside but in the cities where many people gather.’

I am relieved that Devidas is elsewhere, or he might well have tried to cancel the trip. Muzaid, having delivered himself of this gloomy assessment, is once again in good humour.

‘Enough of politics and talk of what most certainly will not come to pass. What you and I who are both travellers will share tonight is travellers’ food. Rajasthan, where my ancestors settled, has meat-eating warriors’ food. Gujaratis are peaceful vegetarians and their food is suitable for a nomadic way of life. Did you know our trading partners were the Portuguese, the greatest travellers the world has ever known?’

He glances across at me, smiling. ‘We are not newcomers to your world. Our dhows were sailing into the West long before the Portuguese or even you British found us. Our ancestors protect us – even I who follow the way of the Prophet believe our forefathers will return in time of trouble to guide us. We are not afraid of anything in this world or the next.’

My host falls silent, as do I, both of us lost in our own thoughts as night falls and the stars begin to appear in the sky. Desert horizons slip over the curve of the earth to infinity by day. At night, when the moon rises, the arc of the heavens is as brightly lit as day.

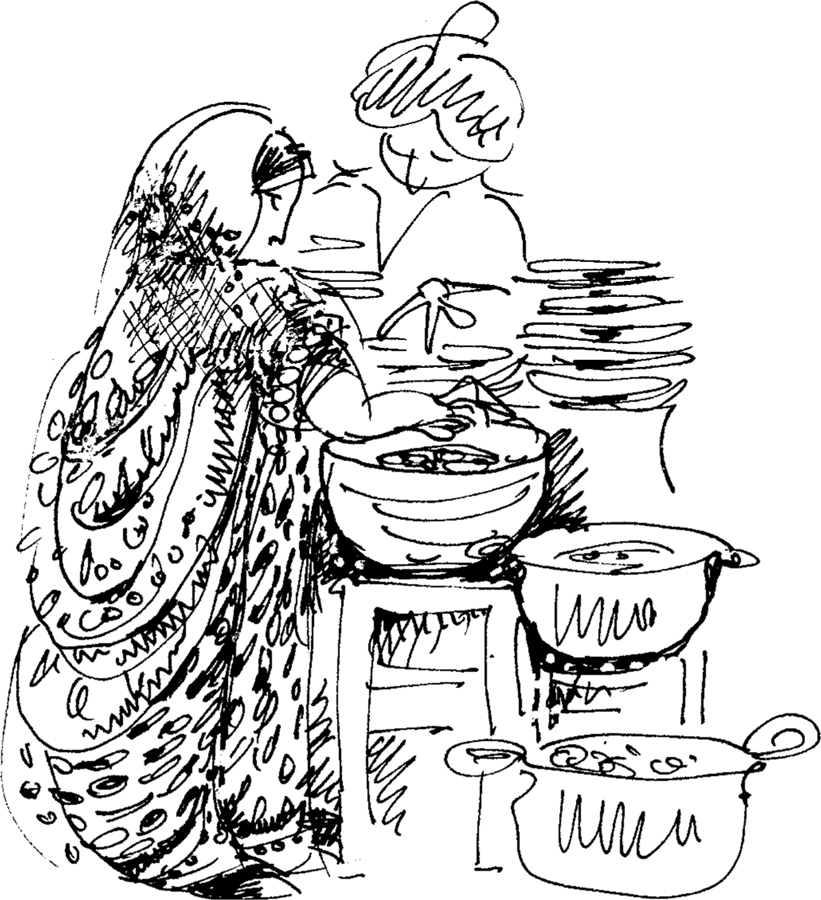

The village is in darkness but for the glow of embers from the cooking fires. The air is already heavy with scented steam and the appetising fragrance of roasting grains. Rabari women, bright as butterflies in crimson silks and beaded bangles, squat down beside the coals, patting out millet dough for roti and keeping a watchful eye on the cooking pots. Goats, sheep and wild-haired children are everywhere.

One of the cooks, a young girl with long dark hair tied back with a flower-printed kerchief, rises gracefully to offer me a freshly cooked roti wrapped round a little scoop of dhal. I hesitate, reluctant to take food out of the mouths of people who have so little.

‘Eat,’ says Muzaid. ‘Sharing food with a stranger is an obligation and a blessing.’ I accept gratefully. I’m hungry. The roti tastes good – chewy, rough-textured and blistered by the fire, and the scooping dhal is sweet and soft and flavoured with cumin. There is, too, a dish of chickpeas stirred with mustard greens, and something simmering in a double-handled, raw-iron skillet, which I don’t recognise at all.

‘This is a dhal made with roti,’ Muzaid explains. ‘I will ask Sarina to explain how she makes it.’

At first the information is given reluctantly, and then, as Sarina demonstrates the action with her hand, with increasing confidence as she waits courteously for her words to be translated.

‘Sarina would like you to know that she learned this dish from her mother, who learned it from her mother and from her mother before her, so you can be sure it’s very old indeed.’

Sarina nods and smiles, watching the effect her words are having as her hands continue to work the roti dough, pushing with the palms, fingers held delicately aloft. Tearing off a piece of dough to demonstrate the texture, she pats it smooth, talking all the while.

Rolling up her sleeves, Sarina rinses her hands in a bowl of water set ready, and indicates I do the same. Muzaid continues with the translation as Sarina slows her movements to allow me to follow her instruction. ‘First the flour must be clean and dry when you measure it into the bowl. To make sure there are no lumps, rub it between your fingers, like so.’ Sarina’s fingers are supple and the flour rises and falls in an airy shower. ‘Now you must add warm water just hot enough for your hand to feel the heat, and work it with the heel of the hand till it comes together softly, like so. Now you must work it like this with your fists till it’s smooth as a baby’s cheek.’

Sarina kneads the dough on the board with her knuckles, fingers bent to make a fist.

‘Now you break it into little pieces – like so – and roll them out like so. See? There’s the first one. Now you try.’

I knead and pat and roll. Mine is not perfect: it comes out a little too thick and oval rather than perfectly round. I try another, an improvement on the first.

‘This is what Sarina says you must know if you want to prepare a dhal with roti,’ continues Muzaid. ‘First you must make some roti-bread, as you have done just now, and dry it in the sun. When you are ready to cook, you must tear it into small pieces. Then you must cook the pieces in a little oil with onion and chilli and cumin. Then you may add a little water and whatever vegetables you please. And you must finish it with this herb – I think you know it well.’

I taste. The herb is cilantro, leaf-coriander. When added to the roti, it occurs to me that there’s a similarity in flavour and texture with açorda, a bread-risotto prepared in Portugal.

Muzaid is watching me with amusement. ‘Sarina would like to know if you have enjoyed your meal?’

Indeed I have, I answer with enough enthusiasm for my words to need no translation.

‘If this is so, perhaps you might care to express appreciation with a token. It has to be something of your own as money is never acceptable in exchange for hospitality.’

I hesitate. I have left all my possessions back in the camp and I have nothing to offer except, I suddenly remember, a faded silk flower pinned on to a pull-on cotton hat of the kind you can fold up and tuck away. The flower belonged to my daughter – Francesca was not yet thirty when she died – and I take it with me whenever I travel, thinking to carry her with me in my heart. It’s time and not before time. I unpin the blossom and hold out my hand.

Muzaid asks me no questions about the gesture, but his silence is companionable as we drive home through the darkness of the night. For my daughter’s sake and mine, I am glad of the company of strangers and the silence and the stars and curve of the heavens and the night.

Early the next morning, with scarcely time to snatch a mouthful of croissant and coffee – Muzaid explains that he likes his guests to feel at home first thing in the morning – Devidas announces our immediate departure.

The reason, he explains, is that we have great distances to cover before we reach the city of Bhuj, capital and gateway to the Great Rann of Kutch, and we must find safe haven before nightfall.

‘I believe no time must be lost, my lady.’

Devidas shakes his head vigorously, head-shaking in India being an indication of agreement rather than dissent.

I am beginning to understand that Devidas does not share his countrymen’s appetite for travel. He is a homebody. In the city he lives with his mother, brother and sister-in-law in one of the more sought-after of Ahmedabad’s suburbs. The women of his household are all excellent cooks, more than capable of preparing the traditional dishes of Gujarat without stepping outside their own front doors, as can be observed from Devidas’s expanding waistline.

‘This is a most important duty, my lady. As I am sure you understand since you are yourself no doubt an excellent cook when you are in your own kitchen and cooking for your family.’

We agree that there is nothing more important than setting good food on the table to feed your family – or anyone else’s, for that matter.

‘Cooking is not a skill I possess, my lady. This I believe to be fortunate since it allows me to truly show my appreciation of what my mother and my aunts and my sister-in-law do so well.’

The balance of our relationship restored with Devidas’s customary blend of charm and good manners – he has his prejudices, but these are never overtly expressed – we proceed on our journey from the Little Rann to the Great Rann in good humour. The journey takes six hours by road and is well peppered with hazards. The middle of the two-lane highway is frequently occupied by a herdsman carrying his shoes on a pole over his shoulders behind a flock of goats, or an ox-cart swaying beneath a skyscraper of cotton-balls, or – once – a group of beautifully dressed women carrying stones in baskets on their heads.

Devidas slows down for a closer look.

‘These women are starvation women. They must pay for their rations from the state – the millet for root and mung beans for the dhal – with work on the roads. These people are poor and the men do not work. These are not good men. What can you do?’

Last year the city centre of Bhuj, regional capital of the Great Rann of Kutch, a glory of eighteenth-century palaces, was reduced to rubble by an unusually violent clash of the earth’s tectonic plates. Thousands of lives were lost. Rehousing is in progress, though this time the buildings are single-storey dwellings outside the city walls. The citizens, however, prefer to camp among the rubble – lighting cooking fires in the street and cooking among the ruins – and have refused to take up residence in the brand-new houses, preferring the devil they know to the one they don’t.

The old city – as much of it as is still standing – is entered through a triple-arched gateway that marks the limits of where people were permitted to build before the earthquake.

Headquarters have advised Devidas of the need to acquire permits from the military in Bhuj before continuing into what is now a militarised zone aimed at discouraging incursions into Indian territory from Pakistan, which is in dispute with its neighbour over Kashmir. If it’s not Kashmir, says Devidas gloomily, it’s Bangladesh. And if it’s not Bangladesh, it’s Pakistan’s support of the Taliban in Afghanistan.

But mostly it’s Kashmir, an insoluble problem left by the British when they drew pencil lines on the map and left the nations of their Empire to fight it out among themselves.

The army office that issues permits to enter the military zone is open for business – never a certainty in India – so I hand over money and passport and watch Devidas vanish into the prefabricated warren of government offices.

Negotiations, Devidas adds with relish, will be protracted and the outcome uncertain.

I settle down to sketch the avifauna – sand-martins darting in and out of the walls, a white-ruffed vulture with bright-pink wattles perched on a dead branch of an upturned tree. One of the humpbacked cows that are everywhere in India watches me through lowered lashes, chewing thoughtfully – although heaven knows what there is to eat in this parched and barren landscape.

I am just dipping my brush in the water-container, ready to make the first mark, when a door opens to release a crowd of excited children let out from school for the mid-morning break.

‘English lady, how are you?’

‘Very well indeed. And how are you?’

‘How you! How you! How you!’

Delighted mimicry gives way to enthusiastic phraseology.

‘Jump up! Jump down! Nose, ears, head, feet!’

This is demonstrated several times before the mood switches to more practical matters.

‘Who are you? How old are you? What is your name?’

As soon as I answer, my young audience is delighted to discover that the fillings in my Western teeth are made of gold. Real gold, the stuff that shines like the sun and is an essential element of every young bride’s dowry.

Word travels like wildfire that here is a visitor of unimaginable wealth and prestige who not only carries her savings in her mouth but shares a name with the Queen of England, and may well, considering her independent air, be Her Majesty herself.

‘Again! Again!’

I open and shut my mouth on demand. Noblesse obliges: my namesake would have done no less. Fortunately – or I might well have found myself obliged to spend the rest of the day with a gaping jaw – the bell in the schoolroom clangs to summon the children back to their lessons at the moment that Devidas re-emerges waving a fistful of papers.

My guide’s negotiating skills have triumphed over all obstacles. Our permits are secured and permission granted to proceed. This is something of a surprise, I point out, since – without wishing in any way to diminish his success – as far as I am aware our itinerary was established in advance and all the necessary authorities notified. Official questions had to be asked and answers verified with his employees in Ahmedabad. Information has been flying around like birds on the wing on a warm evening in search of insects in the desert. Devidas is capable of quite a poetic turn of mind when the need arises.

‘You are not taking account that this is India, my lady,’ says Devidas happily. ‘It is the problem of left hand and right hand. This is most certainly important problem in Gujarat when we are so far away from Ahmedabad.’

I ignore the propaganda and examine the permissions. These extend as far as the villages of the Banni, the limits of the inhabited region of the Great Rann, and allow us to travel within the no-fly zone that separates India from Pakistan. Devidas is looking increasingly cheerful. Warzones, like storm clouds, come with silver linings. Owing to the presence of the military, the road will be in a good state of repair, the villages have access to water from a tap, and mobile phone reception is known to be the best in the state.

As we proceed smoothly down the miraculously bump-free highway, we pass a flock of goats followed by their herdsman talking animatedly on a mobile phone. The goats, practised in the ways of the military, move tidily off-road to allow a convoy bristling with hardware to pass at speed. The tranquillity of the desert is disturbed at intervals by the whine of warplanes patrolling the no-fly zone from the safety of the skies.

The border is a hundred miles to the north of us, the situation is currently stable, and Devidas has taken to winding down the window and waving cheerfully as more military transports speed past.

There is, however, a curfew in place and Devidas is anxious to arrive at our destination, the tourist village of Hodko, before dark.

A curfew imposed by the military?

‘Not because of the military, my lady,’ Devidas answers cheerfully. ‘Because of the wolves.’

There are wolves?

‘This is true, my lady. And lions, too, but they are very far away and the government protects them.’

And does the government protect the wolves?

Devidas frowns. ‘This is a question I am not able to answer, my lady.’

Questions Devidas is not able to answer, I have observed during our week’s acquaintance, indicate political hot potatoes. There are many of these that emerge when the interests of the city do not coincide with those of the countryside, such as predation by protected species – tigers, the last remaining Asiatic lions of the Great Rann, and possibly, presumably, wolves – which is a problem for the rural population that does not affect those who live in the cities and wield political power.

The sun is already setting when we arrive at our destination, the tourist village of Hodko, an enclave of mud-brick dwellings surrounded by a thick wall of acacia thorn that mirrors – at least architecturally – the non-tourist village of Hodko, whose self-sufficient way of life it is designed to support.

The manager of tourist-Hodko, a pretty young woman in jeans and white T-shirt emblazoned with the name of the village, appears from her office to greet us. She has been informed of our arrival and announces herself delighted to welcome us. Her name is Nicole Patel and she is, she explains, a volunteer worker on a fellowship from the University of Chicago who will be happy to demonstrate the good work her NGO is doing to improve health and well-being among the impoverished villagers of the area. One of the attractions of tourist-Hodko to outsiders within India itself, she adds, is the chance to experience the traditional cooking of the self-sufficient villagers of the Banni at a time when India is enthusiastically exploring her roots.

There is paperwork to be completed, continues Nicole, as she leads the way into an office by the gate. No doubt I will already be aware that nothing in India happens without everything in triplicate.

Meanwhile, there is literature available to read at my leisure to explain that the mirror-village of Hodko is a pioneering example of the kind of low-impact, high-value tourism the regional government is anxious to promote. The enterprise offers local employment as a practical solution to the problem of staffing in a remote location such as the Great Rann, at the same time as providing non-tourist Hodko with a share of the profits from visitors.

It is as well for the regional purse, adds Nicole, that the enterprise is funded and run by a non-governmental organisation such as hers, as the cost would otherwise be prohibitive.

The mirror-village of Hodko, she adds as she completes her form-filling, attracts internal rather than international tourism, as it does throughout Gujarat, although there are hopes that this will change. Today, it being Friday and the start of a holiday weekend, there are visitors from Delhi taking a weekend break. The attraction is an exotic location that can be experienced without leaving the country. Facilities, thanks to the presence of the military’s fast broadband and excellent television reception, allow guests to maintain contact with the outside world in safety and comfort.

Devidas expresses his pleasure with a happy shake of the head.

Nicole leads the way across the courtyard of beaten earth towards our accommodation, a cluster of what look like traditional village boma, dome-roofed, mud-walled dwellings much like others we have passed along the road.

‘I’m sure you must be tired and in need of a shower.’

The exteriors have been freshly whitewashed and newly decorated with elegant stylised patterns picked out in mirror-work, but the interiors have been fitted out with everything that might be expected of a modern hotel in Ahmedabad, right down to the hand-woven bedspreads and jasmine-scented toiletries in the adjacent shower-room.

Nicole points out the attention to detail in the cool interior. The traditional fretwork – piercings in the walls – lets in light and air, and the hand-stencilled borders are in traditional leaf-and-flower patterns.

My readers, Nicole continues, might like to know that the enterprise also offers instruction weeks in mirror-work, jewellery-making, weaving, pattern-painting and pottery led by experts from the sister village, non-tourist Hodko. There are plans for marketing the villagers’ skills on the internet, including lessons in mud-work and the construction of dwellings such as these, which have proved remarkably resistant to earthquakes.

‘I hope you will be comfortable. We are proud of our guestrooms, all hand-built by local craftsmen from the villages. Dinner is in an hour and we have a special surprise for our visitors. Please listen for the bell.’

Traditionalists would certainly not approve of the copycat dwellings, but comfort – at least for me and certainly for Devidas, who disappears into his own mud-walled dwelling with a cheerful wave of the hand – is reason to be grateful.

I shower, change swiftly and set off to enquire of Nicole the whereabouts of the kitchen. I am hoping for a chance of hands-on tuition in the traditional cooking of the villages of the Great Rann.

Nicole is busy unloading boxes from a van on to the communal table under a tarpaulin. She sets down the box and turns to me with a smile. ‘You’ll be happy to hear we have a wonderful surprise for you and the rest of our guests this evening – a traditional Kutchi balti.’

I agree this does indeed sound wonderful. Perhaps it could be arranged for me to witness – or even assist – in the preparations?

Unfortunately this is not possible, as the meal arrives ready-cooked from non-tourist Hodko. On the other hand, says Nicole, observing my disappointment, I might like to watch the preparation of the roti, the flatbreads that are cooked fresh and are always the most important element in any meal in India.

The roti-maker of the evening is known to be particularly skilled at producing the perfect balance of chewiness, nuttiness and elasticity in her flatbreads, and she will be cooking on the open fire on an earthenware bake-stone, just as she does in her village.

I return with my sketchbook and paint box at exactly the moment when a battered army vehicle with ‘Hodko Tourist Village’ over-painted on the military insignia rattles through the gate.

The driver begins to unload silver trays on to a wooden table under a tarpaulin beside the dining area while our bread-maker, a motherly old lady in an impeccably pressed blue-and-white overdress, spreads a cotton sheet on the ground in front of the fire and begins her preparations. As she works, I make notes in my sketchbook. Wholemeal roti is the simplest of all flatbreads, and as with all such simple preparations, excellence depends on the skill of the cook. While I’m well used to baking yeast-raised bread in my kitchen at home, unleavened bread is a skill I’ve never mastered – and probably never will.

Rapidity and sureness of touch can only come with a lifetime’s experience, as I know well from accepting many an invitation to emulate a skill. My notes, when deciphered by the light of a hurricane lamp in the boma after the generator is switched off at midnight, are lengthy and detailed.

First there must be the correct proportion of hand-milled flour to salted water, to make a soft dough that can be worked to silky smoothness with the heel of the hand. When the texture is judged correct, the baker breaks off pieces the size of a pullet egg and swiftly works them smooth. Speed is essential. Then, with rapid movements of a rolling pin on a wooden board, each piece is rolled in turn with perfect accuracy to a size convenient for the hand.

Once all are prepared, the bake-stone is set over the campfire – actually a stick-fire lit in the cooking area in the middle of a sandy depression – and heated to the correct temperature. Once this has been tested with a hand held horizontally over the surface, the flattened discs of dough are flipped on one by one. Each is toasted on one side only and stacked in pairs, brushed between the layers with melted white butter. The task is completed with extraordinary swiftness and grace.

‘Bravo! Such expertise is wonderful to behold, is it not?’

It seems I am not alone in my admiration of the bread-maker’s skill. One of the other guests, an elegant middle-aged woman in a beautiful dark-red sari, has been watching the work with equal interest. Her English is perfect and I’m glad to find a friend who shares my enthusiasm.

‘You are the journalist from England, are you not? You are the only one of us who isn’t – how shall I put it politely? – one of the natives. And I can see you’re interested in the cooking.’

She presses her palms together and bobs her head in the traditional greeting between strangers.

‘My name is Indira and I am from Delhi. If you are alone, perhaps you would care to sit with us, my friends and I, so we can enjoy the meal together.’

I accept the offer gratefully.

Devidas has already disappeared, in search, I suspect, of access to fast broadbrand and a well-earned rest from his charge’s endless questionings.

He has my sympathy. My maternal grandmother, irritated at having to take care of a schoolgirl when she was having her clothes fitted in Paris, told me that curiosity killed the cat. She was wrong. Curiosity is a gift, a treasure, a compass by which to set a course.

A bell rings to summon the rest of the guests, some of whom – a family group with two well-behaved teenage children, a young couple and half a dozen smartly dressed middle-aged women, including Indira – are already clustered around the table where the trays are laid out in rows.

Each tray has been provided with an array of little bowls. Indira guides me through the recipes. Here is okra, bindi, cooked with chilli and cumin; these are fritters, pakora, prepared with millet and onion. Here is potato with cumin, and this, a soupy yellow dhal with nigella seeds, has been stirred with the white goats’ milk butter used to brush the roti. And this little pile of bony joints is chicken stewed with cinnamon and chilli.

I might be surprised, she continues, by the presence of chicken since I will already be aware that most Gujaratis follow Gandhi’s example and stick to a vegetarian diet. This is not so in the big cities such as Mumbai and Delhi, where all but the strictest Hindus eat chicken and fish.

In the tribal areas of the Great Rann, she continues, some villages are Hindu and some are Muslim. Hodko is a Muslim village that serves a balti. Had Hodko been a Hindu village, the meal would have been a thali. This can be confusing for the visitor, Indira explains, but there are other indications of differences.

Among these are certain spices when treated in a particular way. I can assume that if the cumin is toasted in a dry pan and used to finish a dish, the family is Hindu. Cumin tossed in hot oil before the cooking liquid is added is the Muslim way of doing things. This culinary rule is by no means set in stone and every household has its own preferences, but as a general rule, preliminary frying and the use of an iron pan is Muslim and simmering with a liquid in a cooking pot is Hindu.

Devidas, arriving late to the party, inspects the array with disapproval. He has already told me that Muslim food is too greasy for a Hindu. His face brightens, however, when he spots a dish of what looks like hand-rolled noodles in a caramel-coloured sauce.

‘This is what we call idli. It’s very special. All Indians love it,’ says Indira, observing Devidas’s enthusiasm with a smile. ‘Please to help yourself.’

Devidas cups his hand, bends his head and, in a flash, the mouthful is gone. ‘This is very good, my lady, very good. There is nothing more delicious in all India. Do as I do, cup your hand.’

‘Like so?’

Obediently I cup my hand.

‘Not quite.’ Indira places her right hand beneath mine to form a double cup and squeezes gently. ‘You must close the fingers tight, like so. Now take it up with the hand, like so. Now bend your head and take it with your tongue, like so.’ I do as I am bid. When I raise my head, most of the buttery sauce has trickled through my fingers and into the bowl.

Indira laughs. ‘It will come. This is hard for you but easy for us. It’s natural because it’s how we use our hands, like making roti – our fingers just make the shape.’

Later that evening, with Devidas retired early to his billet, I join Nicole and Indira and fellow guests for a nightcap round the hearth-fire. The temperature drops sharply in the desert at night, and the warmth of embers is welcome.

All the other guests are from Delhi, mostly in finance. Hodko is expensive, so only the rich can afford it, and talk soon turns to ways in which the villagers can be encouraged to earn money for the things they need. English is the common language – the rapid-fire colloquial Indian version that can be hard to follow for those unaccustomed to its cadences – although this may well be a courtesy to my presence as the only member of the group with no alternative.

Poor people such as the tribals, there’s general agreement, don’t want to live in the old way once they experience the new. Television and mobile phones are undeniable improvements to the traditional way of life in the villages, and to pay for service, once the military are no longer providing it for free, you need an income, however small.

For an income, everyone agrees, you need a business. For a business you need a bank. Indira herself is in microfinance. Even her name is an indication of the desire for change: many girl babies of her generation were named for Mrs Gandhi. Micro-finance, she continues, works well because it is paid to the women. Women are social entrepreneurs, as she is herself.

‘Is this not also true in Britain?’

I hesitate. Women are nowhere near parity in Parliament and as leaders of industry, and this, I admit, is proving hard to change.

Indira laughs. ‘We in India are showing you the way. Some of us here are independent women, are we not? We are travelling alone and we have no fear.’

She holds up her hands. ‘Look at me. I have gold rings. I own my own house. My first micro-loan bought me a basket. Then I bought a pushcart. Now I own my own shop. If you help one woman, you help the whole family. And women can reach other women. It affects everything – health, childbirth, education. We are making progress. There is no alternative. Women can no longer be treated as the property of husbands and fathers, worthless unless protected by a man – this is the source of all our problems.’

Another member of the group of middle-aged women travelling on their own, Sonali, is not sure that change is always for the better. Even here in the Great Rann, where life is still lived much as always, pleasures are no longer as simple as when she was a girl.

‘I myself was from one of the villages of the Banni, but I was fortunate to marry a husband who made enough money for us to live in Delhi. I am grateful he left me well provided for in my widowhood. But I still have pleasant memories of my childhood. I remember when my grandmother made butter, her arm bracelets made a special sound as she churned, and then we always knew there’d be something delicious for dinner. This was her role, and I never heard her wish for any other.’

Sonali smiles and glances round at her audience. ‘And I remember that my grandmother taught me that when a woman goes to meet her husband before she is married, she walks on tiptoe so her anklets don’t betray her.’

Indira smiles. ‘And when she goes to meet her lover, what then?’

Sonali rises to the challenge. ‘This won’t happen. She will be too busy churning the butter.’

I wake late to the rattle of the returning army truck. This time there are two vehicles. The second, open-topped with benches for passengers on either side, looks like a safari jeep. An excursion to the real Hodko is available for those who wish to take advantage of the opportunity. Safari jeeps bring thoughts of wolves.

Devidas anticipates a busy morning on the internet. ‘You need have no fear, my lady, that I will not be accompanying you,’ he tells me. ‘This place is very wild but the army will protect us.’

Nicole shepherds the rest of her guests into the vehicle. We must understand, she explains when we are all settled in our seats, that the villagers do not usually welcome outsiders. But she has managed to convince the villagers that since each village specialises in a particular handicraft, direct selling will be to everyone’s advantage by cutting out the middleman. Some of the villagers are potters, some weavers, some metalworkers and others, Hodko among them, specialise in embroidery.

‘I advise everyone to open their purses,’ she adds with an encouraging smile. ‘There will be many bargains.’

First we should know a little of the remarkable construction methods of the village. Hodko’s round-walled, mud-brick bomas are roofed with tiles supported on wooden struts drawn together like the closed petals of a flower – a construction that ensures the petals fall outwards when shaken by an earthquake, leaving the inhabitants unharmed. The traditional building material, mud strengthened with fibrous cow-dung, is similarly earthquake-proof, crumbling when the walls collapse and re-usable after the monsoon. From an architect’s point of view, though the mud walls would be no defence against bombs should war break out in earnest, since all the building materials are recyclable, reconstruction would be quicker, easier and cheaper than with conventional buildings.

There are many additional lessons to be learned from traditional methods of construction. Interior walls are lime-washed, a natural disinfectant. Pigments traditionally used for decoration are prepared with home-grown chilli and turmeric and recyclable mirror-work, allowing restoration of beauty as well as shelter.

Technology has already changed ways of building. The struts that support the petal-shaped roofing are made of beaten metal rather than peeled branches bent to shape, and the tiles are industrially moulded concrete rather than hand-made pottery. The traditional patterns of intertwining chillies, flowers and leaves and sprouting wheat-grains – the paisley pattern – are painted around windows and door with shop-bought paints.

Change is here to stay. Money is needed not only to buy materials for construction, but for mobile phones and televisions as well as oil, salt and spices. And even an idealist such as Nicole cannot disagree with the value of medical attention and the provision of care in childbirth. The young are hungry for what’s advertised on their screens, even though their parents are still self-sufficient in the basic necessities of food and shelter.

Preparations for meals, as in the Rabari village of the Little Rann, take place in the open air. The cooking fire is lit in an earthenware fire-bowl which is open on one side, the heat of the flame controlled by pushing the sticks into the coals. Others are double-bowled, shaped like a footprint but with one wall taller than the other, allowing the cooking utensils to be placed closer or further from the fire. The vegetables which make up the bulk of the meal – potatoes, aubergines, radish greens, tomatoes, garlic – are grown in an enclosure just behind each boma, protected from the goats with a barrier of cut acacia thorns.

I abandon the rest of the party to their bargaining for the beautiful embroideries to inspect the contents of the cooking pots, making notes in my sketchbook. My rough sketches, I have found, are a diversion for those involved in the more serious business of the cooking itself, ensuring a friendly welcome and answers to questions.

Today I am taking note of the ingredients and the way they’re used. Little yellow potatoes stored in a wire basket hung on a hook on a rafter are set to simmer in a sauce of peanut oil, garlic and tomato to produce a scooping-dish, aloo ki kari, to eat with roti. At another fireplace, radish greens, well rinsed and shredded, are stirred into hot oil with crushed cumin seeds and a handful of salt and allowed to soften in the heat. In the scraped-out ashes of a third cooking fire have been set half a dozen aubergines, a double-purpose crop since they can be dried for storage, which are left until soft and squishy and blistered black.

‘Bharta, my favourite,’ says Nicole, leaning over my shoulder to inspect the quick rough sketch of aubergines roasting over the flame. ‘When they’re ready, you scrape the pulp of the skin and mash it in hot oil with garlic and ginger and maybe a little chilli. It’s delicious.’

Nicole volunteers as translator of my questions to the cooks in exchange, she suggests laughingly, for the aubergine sketch. I agree without hesitation – I can always take a copy and goodwill is more valuable than marks on paper.

Millet is grown as a crop-share with the landowner because the tribals are not traditionally land-owning – a political weakness, Nicole adds in a quiet aside, which allowed others to claim ownership, a situation which suits the state since landowners can be taxed.

Three or even four crops a year are possible in Great Rann. In a year when the rains are good – three in every five on average – four acres and one crop-share is enough to supply a household of six adults and their children and pay the landowner.

In a bad year, the state steps in and pays famine money to families in distress, demanding work for the public good in return. If the rains have failed, mothers and daughters – the famine women passed on our journey – repair the roads. The milling of the grain is paid for in cash. Households keep their own grain and bake their own supplies of roti, both dried for storage and fresh. Three milk-goats, productive for half the year, are sufficient to supply a household with fresh milk and curd cheese, and for the preparation of butter stored as ghee. The buttermilk provides minerals and protein, and the ghee is used to enrich rather than fry.

Goats’ milk is particularly rich, more so than cows’ milk, but less than buffalo. A litre of goats’ milk can be turned into half its own weight of butter in less than a half-hour if the churner is skilled.

When the butter comes, adds Nicole, you’ll hear a soft bumping sound. The churn is a metal pot with a wide-mouthed neck that supports a wooden paddle attached to a spindle – a string wound round the paddle like a yo-yo – pulled back and forth until the fat separates from the liquid and the butter comes as lumps of semi-solid butter melted down for storage as ghee. The buttermilk is drunk fresh and cool, or hot and spiced. Nothing is ever wasted. Goat dung, the other end of the milking-cycle, is used to heat the bake-stone for the flatbreads – roti or chapatti, it’s all the same.

The interiors of the bomas are dusted, swept and spotless. Prized possessions and cooking implements are stacked round the walls on shelves moulded from the same building material as the walls. Possessions are a visible show of wealth. Embroidered covers for beds and furniture are a young woman’s dowry. Work begins as soon as a little girl is able to hold a needle, and the embroideries are folded and stacked on a shelf against her marriage day, a source of wealth.

As she watches her visitors bargain for the beautiful handiwork spread out for sale on sun-bleached cotton sheets in front of each boma, Nicole admits to mixed feelings about the influence the tourists will have on village life if her plans succeed.

‘Tourists bring money and choose what they buy as well as what they eat and wear and take home as presents. In Hodko, for instance, where the handiwork is Muslim, the embroidery has lots of little bits of mirror. In a Hindu village, it’s plain. If the one sells better than the other, the one that’s not successful loses popularity with the embroiderers, whatever their traditions, and in time it will disappear, just as the culinary differences between Muslim and Hindu are already disappearing. Perhaps this is good, perhaps not. Religious prohibitions preserve a way of life but the consequences are unpredictable.’

Indira breaks off from her bargaining to join the discussion.

While her family are devout Hindu and never eat meat, there are many who do, and she herself has many Muslim friends who are happy to enjoy the vegetarian dishes she sets on the table. The same is true of embroideries. Everyone knows the difference between Muslim and Hindu handiwork and she herself has an outlet in Delhi which can sell everything she buys from both sides of the religious divide. The money the villagers receive, particularly the women, can give them independence and political influence. Western tourists, she says, can also be an influence for good. Westerners don’t take sugar in the chai available by the glass at every roadside stall, and although Indians have a very sweet tooth, they follow suit because they think it’s more modern. As a result their teeth are much improved and dentists are no longer kept busy repairing the damage. Instead they offer their services to whiten teeth because even the poorest want to look like Bollywood stars.

The villagers of the Banni have never had rotten teeth. Honey from wild desert bees has always been the sweetener and this is always in limited supply and not at all easy to gather.

While this may be true, reasons Nicole, what is also true is that, as more money comes into the villages, people prefer to buy jaggery – cooked-down crystallised palm-syrup – and the new generation of village children have to be sent to hospital with toothache and rotten teeth.

Next day we are due to return to the capital. The journey will be long and tiring but is eagerly anticipated by Devidas, who is up bright and early – long before anyone but Nicole and Indira are about.

On Indira’s suggestion, I snatch a quick breakfast of leftover roti with ghee. By the time I reappear with my luggage to take my leave and send messages of appreciation to my fellow guests, Devidas is already filling the car with petrol at the expense of the NGO under Nicole’s watchful eye. More forms will need to be filled in, as every penny must be accounted for.

Back in Ahmedabad – a journey that seems to take a quarter of the time it did on the outward journey – and safely delivered to my hotel, I am greeted by Devidas the following morning, the last day of my visit, with an invitation.

As promised, his mother, sister-in-law and brother, two nephews and their wives and three grandchildren will be delighted to welcome me to the midday meal in the family home. This is exactly what I had been hoping for, a chance to experience the urban cooking of the region in its proper setting. There is always a difference between the culinary habit of the city and that of the countryside, since urban cooks, shopping daily in the marketplace, have a wider choice of seasonal produce than country-dwellers.

I am invited into the busy lean-to kitchen, joining the senior ladies of the household – mother, aunts and daughter-in-law – to observe the preparations. Much is already under way. As a present, I have brought a pocket-sized cookbook of my own – Classic French Cooking – which carries my own illustrations. We lack a common language, so I take out my sketchbook and paints to show how the pictures were made.

The most important dish – apart from the flatbreads – is a pilau dhal – rice and lentils, the classic double act of the Indian kitchen – already prepared and awaiting its finishing ingredients: stems of green garlic, toasted cashews and fresh green lentils, tender and sweet as new peas.

Devidas’s sister-in-law, Sarina, a handsome young woman with sparkling eyes and a ready smile, sets me a task. I am permitted to pod the lentils, two to each pod. My fingertips turn brown from the juices and Sarina, laughing, rubs off the stain with lemon juice.

The dhal and rice are ready. Last to be prepared is the bindi bhaji, okra fritters made with lentil and gram flour and flavoured with dried onion. Devidas is summoned to explain the onion. Spiced, fried, sun-dried onion flakes acquire some of the characteristics of hing, an expensive ingredient which keeps more or less indefinitely when stored in lump form and doesn’t release its pungent odour until crushed and heated in oil, when it becomes wonderfully mild and gentle. Dried onion, while not permitted to high-caste Hindus, delivers mildness and gentleness but without the expense.

There are two kinds of chutney to be prepared, one fresh and scoopable, and one dry and suitable for sprinkling. The two together, explains Devidas as the fragrance of mint and sesame rises from pestles and mortars, is for balance and additional protein that can be lacking in a vegetarian diet. The sprinkling chutney, roasted sesame seeds pounded with chilli and salt, is for savour. The wet chutney, a raita, is prepared with home-made yoghurt stirred with little shards of fresh mint from the garden.

The meal, once set on the table and the family assembled, is consumed with remarkable rapidity. On a normal day the men, as the main breadwinners, are served first to allow them to return to their place of work without delay. Today, in deference to my presence as a female guest, we all eat together.

Sarina takes her place by my side and guides me gently in the delicate art of eating with my fingers from the communal dish set in the middle of the table. Ordinary households do not serve their food in separate little dishes, as happens with the thali. Eating must be done without finger-licking or straying into anyone else’s portion. Everything is placed on the table at the same time and participants are expected to eat only as much as they need. Taking more than a single mouthful at once is bad manners, and heaping your plate, should this be provided, is even worse.

Eating with the fingers without giving offence has been a steep learning curve, and I’m pleased that my ability to scoop and suck is improving rapidly. Quite soon my table manners will no longer be a source of amusement and I might be almost presentable in polite company. When I share this thought with Devidas he laughs delightedly, translating my words for the benefit of the rest of the family, even though the younger members have a good grasp of my native tongue.

This is an important occasion, Devidas continues proudly, when an ordinary Gujarati household of modest means is honoured to welcome a distinguished journalist such as myself at the family table, thereby confirming the friendship between our two nations by the sharing of good fellowship – a situation all too uncommon in the world of today, when those who have lived in tolerance and mutual respect for many centuries find themselves at the mercy of the will of others.

I rise to my feet and reply with equal circumspection that I too am proud to represent my own great nation, which continues to celebrate a close relationship with a civilisation far older than her own. A civilisation, I continue, warming to my theme, that has proved so resilient over the centuries that the rest of the world cannot but admire and hope to emulate the philosophical and practical principles by which so many have lived in harmony with nature as well as their fellow man. This, I conclude, is the most important of the many lessons that India can teach the world as she moves into the new millennia.

With the speeches concluded and the meal finished and cleared – as an honoured guest, I am forbidden to help – Devidas suggests a tour of his mother’s pride and joy, her vegetable garden. This turns out to be a double row of five-gallon oilcans stacked round a small paved courtyard just outside the kitchen door. The crops – fat little tomatoes ripening red on the stalk, clumps of golden lemongrass stalks, and bright-green bonsai trees of little-leaf basil – are chosen for physical and spiritual balance. The tomatoes, being sweet and juicy, are for pleasure; the lemongrass is used in a soothing infusion for health; while the basil is grown as a temple offering to ensure the household’s spiritual welfare.

‘It is natural among Hindus of north India such as ourselves to follow the principles of Ayurveda. These, as you will certainly know, my lady, mean that consideration is given to happiness, health and spiritual welfare whenever food is set upon the table, even if this is only roti and a pinch of salt. My mother has followed these principles all her life. And to make sure everything she cooks is fresh, she shops every day – sometimes twice a day, if the weather is hot. Everything must be carefully judged, as no food can be kept from one day to another, so there is very little waste.’

Furthermore, even the women who go out to work every day cook everything fresh at least once and sometimes twice a day.

Meals, however, are not usually the lavish feast we have just enjoyed. Sometimes the only hot food might be freshly baked chapattis to eat with a spoonful of yoghurt stirred with mint, and maybe a little chutney of ripe tomatoes. And anyway, in a household such as this, there is always a grandmother to help out with all the things for which nobody else has the time or patience. This must also be so in my own country, is it not? Is it not true that grandmothers are the most useful member of any household?

My reply – that I know this because I am seven times a grandmother myself – is greeted by the sisterhood of the kitchen with admiration and a warm embrace.

I rise to take my leave and offer gratitude and thanks. Sarina accompanies me to the door and walks with me a little way to find a tuk-tuk. She wants to reassure me that their meals are not always so luxurious.

‘When it’s just the family and we are not receiving visitors, we will eat perhaps one dhal and two or three vegetable dishes, something simple.’

I must understand, too, that nothing left over from a feast such as ours will ever be wasted.

‘Anything we do not eat is given to the holy men and beggars who come to our door at sundown. It is a privilege to be generous, and we must be grateful to those who accept alms from our hands.’

If Gujarat is the poorest and least favoured by nature of India’s regions, she is surely the richest in spirit.

GARAM MASALA (SEASONING SPICE)

This all-purpose seasoning mix – garam is ‘hot’ and masala is ‘spice’ – is the secret ingredient of the Indian kitchen, adding savour at any point in the cooking process but particularly as a finishing sprinkle. Feel free to experiment with the balance until you get it to your liking. Commercial blends are not a patch on your own, since there is no guarantee of the freshness of the spices and they often include unnecessary thickeners. Buy and store your spices whole and they’ll last for a year.

Makes about 175 g

3 tablespoons cardamom pods

2 tablespoons coriander seeds

2 tablespoons cumin seeds

1 tablespoon whole cloves

1 tablespoon black peppercorns

1 finger-length piece of cinnamon stick or cassia bark

Crush the cardamom pods and extract the seeds, discarding the shells. Crush the coriander seeds and blow away the chaff.

Pack all the ingredients into a clean coffee-grinder and pound to a powder. You can do this by hand with a pestle and mortar, but the grind will not be so fine and it takes a lot of patience. Store in an airtight tin or jar for no longer than three months.

To use in a sauce, release the aromatic oils by toasting the mix for a few seconds in a dry pan, then add to whatever needs to be spiced – curries, chutneys, chai.

Possible additions are ground ginger, grated nutmeg, chilli powder, crushed fennel seeds and crumbled bay leaf. In savoury dishes, cassia is preferred to cinnamon. For sauces thickened with yoghurt or cream, omit the coriander and cumin. To spice a milk chai to accompany a festive dish of sweet rice, noodles or idli, the basic mix is nutmeg, cardamom, ginger and saffron. To use with clarified butter, ghee, allow the butter to brown a little before you add the spices.

Unleavened scooping-breads – roti and chapatti – served fresh and hot from the bake-stone are the most important element in any meal in India, eaten in the morning, at midday and in the evening. In a well-ordered household, it’s the privilege of the senior wife to prepare them herself and send them out as soon as they’re done. You can vary the recipe with a handful of chickpea flour (besan) or any other milled pulses; for millet-bread, replace a quarter of the wheat flour with ground millet (bajri), a robust, sun-loving grain which flourishes in desert conditions and delivers a chewy, toasty flavour. The higher the proportion of wheat flour, the lighter the bread, though this is not always desirable, since chewiness and solidity is good when you’re hungry and there’s not much else on the menu.

Makes 16

500 g stoneground wholemeal flour

½ teaspoon salt

250 ml warm water

1 teaspoon vegetable oil

To finish

2–3 tablespoons melted ghee

Sift the flour with the salt into a large bowl. Make a well in the middle and add the water and oil in a steady stream, mixing with your hand, until you have a softish, sticky dough.

Dust the table with a little flour, tip out the dough and knead it thoroughly for at least 10 minutes. Or let the processor do the work: add the water gradually to the flour and stop as soon as it forms itself into a lump (a minute or two), then finish kneading by hand until silky and smooth.

Work the dough into a ball, cover with cling film or a damp cloth, and set aside for an hour or so – overnight is even better. Knead the dough for another minute or two, cut it in half and roll each piece into a rope as thick as your thumb. Break off a nugget the size of a walnut, work it into a little ball and pop the ball into a plastic bag to keep it soft until you’re read to cook. Continue until the rope is all used up. Wait to bake until just before you’re ready to eat, so that the breads are fresh and hot – now you understand why the women don’t sit down with the men.

Dust a dough-ball with a little flour, press to flatten, and roll or pat into a thin pancake, about 15 cm in diameter – this is easiest if you sandwich it between sheets of cling film. Roll from edge to edge, beginning with the side nearest to you, pressing and pushing with a firm back-and-forth movement, until you reach the other side, then turn the dough a quarter circle and roll it again. Dust lightly with flour, drop it back in the bowl and cover with cling film. Continue until all the dough-balls are rolled out.

Heat a heavy iron pan or griddle and rub lightly with a scrap of linen soaked in oil or ghee. Drop the first flatbread on to the hot metal and wait until little brown blisters appear, about 1 minute – if the surface blisters black immediately, the griddle is too hot; if no black bits appear at all, it’s too cool.

Turn and bake the other side for another minute, pressing the edges with a folded tea-towel to trap the air in the middle and create bubbles. Transfer to a basket lined with a cloth, and keep everything covered. Continue until all the flatbreads are cooked.

If you cook on gas, the roti can be puffed up before serving. Hold the roti in the flame for a few seconds, then turn it to toast the other side: magic. Good with a fresh tomato chutney: chopped ripe tomatoes with a little finely chopped onion and coriander leaf.

MOONG DAL KI ROTI (MUNG-BEAN WRAPPERS)

Poured pancakes made with a purée of mung beans, a variation on the usual scooping-breads, to be eaten with spiced yoghurt and a ginger and chilli paste.

200 g yellow moong dal (mung beans)

½ teaspoon asafoetida (optional)

1 small green chilli, de-seeded and chopped

1 walnut-sized piece fresh ginger, peeled and roughly chopped

oil, for frying

Rinse, wash and soak the mung beans for at least 6 hours. Drain thoroughly, transfer to a food processor and grind to a smooth paste. Add the asafoetida (if using), chilli and ginger and blend thoroughly. Add enough water – about 150 ml – to make a thin cream.

Heat a heavy iron pan or griddle and rub with oil. Pour half a ladleful of batter on to the hot metal, wait for 3–4 seconds to allow the underneath to set a little, then, using the back of the ladle, spread the batter out in concentric circles, forming a pancake as wide as your hand. Trickle the surface with a little oil. Wait for 2 minutes until the top begins to dry, and then turn it carefully to cook the other side. Transfer to a cloth to keep warm. Continue until all the batter is used up and you have a pile of warm pancakes. To reheat, wrap in foil and heat in a low oven.

Serve as a starter with a yoghurt dip and a chilli-ginger paste, or as a main course with your favourite vegetable curry. Perfect, too, as a high-protein wrapper for vegetarian barbecued food.

BHARTA (SMOKY AUBERGINE DIP)

The secret is in the smokiness delivered by the roasting process – easily achievable over a campfire or barbecue, possible on a gas flame, impossible on an electric hob, and just possible under a grill or for a couple of hours at bread-baking heat in the oven.

Serves 4

3–4 large firm aubergines

2–3 garlic cloves, peeled and thinly sliced (optional)

1 teaspoon ground cumin

salt and pepper

Wipe but don’t hull the aubergines. Make a few slits in the skin, push in the garlic slivers (if using) and set them to roast very slowly over an open flame, turning them regularly, until the flesh is perfectly soft and the skin blistered black. Cut the aubergines in half, scrape the flesh from the skin and pound it with a pestle and mortar along with the garlic (if using) until you have a perfectly smooth paste. Season with cumin, salt and pepper.

PILAU DHAL (BUTTERED RICE AND DHAL)

A simple combination of grains and pulses – also known as khichree – is spiced and enriched with butter to make it a festive dish. Dhal and rice counts as poor folks’ food in the rice-growing area of India, but in Gujarat, which is not a rice-growing area, it’s a dish for a celebration.

Serves 4–6

250 g yellow moong dal (mung beans)

250 g long-grain rice

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon garam masala

1 teaspoon cracked black peppercorns

½ teaspoon ground turmeric

2 tablespoons ghee (clarified butter)

Soak the mung beans and rice together for half an hour, then drain.

Transfer the drained mung beans and rice with the salt, garam masala, pepper and turmeric to a large saucepan and add 500 ml water. Bring to the boil, turn down the heat, cover with a cloth and lid, and simmer until the rice and mung beans are perfectly tender – 30–40 minutes – adding more boiling water if necessary. The finished dish should be juicy but not soupy.

Stir in the ghee. Taste and correct the seasoning – you’ll most likely need more salt.

ALOO KI KARI (POTATOES IN SPICED TOMATO SAUCE)

A spicy sauce for plain-cooked potatoes made with fresh tomatoes ripened in the sunshine of the Great Rann is cooked down until nearly caramelised with onion, garlic, chilli and cumin.

Serves 4–6

1 .5 kg new or old potatoes, scrubbed and cut into chunks

1 large mild onion, peeled and finely chopped

2–3 garlic cloves, peeled and finely chopped

2 tablespoons ghee

1 kg perfectly ripe tomatoes, scalded, skinned and diced

1 teaspoon cumin seeds, crushed

½ teaspoon dried red chilli

salt

To finish

coriander leaves (optional)

Set the potatoes to soak in plenty of salted water while you prepare the sauce.

Fry the onion and garlic very gently in the ghee in a large saucepan, stirring regularly, until the vegetables soften – allow at least 20 minutes and don’t let them brown. Add the chopped tomato, cumin and chilli, salt lightly and leave to cook right down over a very low heat into a thick, almost caramelised sauce – allow at least 40 minutes depending on the wateriness of the tomatoes. This sauce – also known as gravy, a relic of the Raj – can be prepared in advance.

Cook the potatoes in salted water until perfectly tender – allow 20 minutes. Drain, reserving a cupful of the cooking water. Dilute the sauce with enough of the reserved water to coat the potatoes. Finish with a sprinkle of fresh coriander leaves – or not, as you please. Save any leftovers to set out in the desert as an offering to whoever might be in need, human or otherwise.