In that place there stood a mighty oak tree, much beloved by Brigid, indeed blessed by her. The trunk survives to this day and none dare cut it with an axe. It possesses a property so great that any person able to break off a part of it with their hands can hope thereby to win God's aid. Many miracles, by the blessings of Blessed Brigid, have been received through that oak tree.

—ANIMOSUS, C. 980 C.E. Description of an oak tree, presumably the one at the Shrine at Kildare, dead at the time of Animosus's writing.

One fog-drenched night on my first visit to Ireland, I stood on the back patio of a rented cottage with two friends. As each mist-billow passed, the line of trees at the edge of the property seemed to move closer to us. We stood frozen, admitting we were seeing the same thing. Could trees really walk like they did in the stories we heard as children and was it really happening in front of us? We finally ran back into the cottage when it looked as though the trees had advanced to the line where the patio met the grass. In the morning light, the trees were back on the other side of the lawn. We were confused, scared, and completely thrilled. Something magickal had happened. It hadn't been substance; we had all been quite sober. Maybe it was an optical illusion created by the fog, or a touch of lingering jet lag. Or maybe Ireland is just magickal enough a place that trees walk across lawns in the middle of the night. I still have the muscle memory of petrified terror and delight, and probably always will.

From the base of Gog, the more than 2,000-year-old oak tree in Glastonbury.

There is something profound to ancient trees and their presence in Celtic culture of old. When I visited Glastonbury for this book's research, I also visited the famous ancient oaks, Gog and Magog, each over 2,000 years old. One is now dead but its trunk still stands. The other is still alive. These oaks are believed to have been part of an entryway to the Tor, perhaps part of a long ceremonial walk, used by the Druids. I wept when I first touched the great trunk of one of the oaks. I can be stoic and analytical about these kinds of things. My profound moments trickle in over periods of time and reflection, but this one smacked like a wave. I've never had such an immediate and visceral reaction to any object without any context at all before or since. Something about oak is profoundly significant. Oak may be a lesser-known area of patronage for Brigid, but it is perhaps what most reveals her Druidic legacy.

With sacred mistletoe the Druids crown'd

Sung with the nymphs, and danc'd the pleasing round.

—WILLIAM DIAPER

In the ancient Celtic world, the land was covered with thick forests and the oak trees were massive. The oak was considered the Druid's tree. Some have even argued that the very word “Druid” is derived from an old term for oak. Having yet to be cleared, the oaks had grown to proportions dwarfing most of the oaks alive today. Its size, antiquity, and remarkable resistance to fire, disease, and insects may have inspired the Druidic title for the oak as the King of the Trees or The Magickal Tree. For reasons unknown to me, the oak is more likely than other trees to be struck by lightning. Because of this, the Druids may have connected the oak to thunder and sky Gods. Oak acorns found on the forest floor fattened domestic pigs, ensuring healthy livestock, and oak bark could tan leather. The sturdy, water-resistant wood of the oak provided construction of sea-worthy ships for trade and travel. Naturally, the oak was greatly revered by the Celts and, in particular, the Druids themselves.

Whether for their power and strength, the seemingly indestructible quality of the rootless mistletoe growing out of oak bark, or the food supply for their livestock, the oak had a profound significance in Celtic spirituality. Oak received special veneration from Druids, who had fixed dates and prescribed ceremonies for cutting the sacred mistletoe with a golden hatchet. Both oak and mistletoe were primary focuses of Druidic worship. The boughs of the great trees provided the temples for their rites. Some earlier writers suggested that religious rites occurred in urban areas while some writers, particularly those who wrote of the mythical shrines on Anglesey Island in Wales, claimed the Druidic rites only ever happened in dark, thick forest and sacred groves. This might indicate that the increased Roman influence pushed the Druid and the Celtic religious practices farther into remote areas, or it may simply indicate different sects of Druids practicing in different areas.

Regional oaks marked the center of community worship and were pillars of honor and local cultural identity. Some myths indicate the felling of an oak was a political blow, such as one myth in which the King of Tara Hill cut down a massive oak in another region to humiliate that region's ruler. The mighty oak was also an obstacle for the ancient Celts. Because of its size, it was probably a very difficult tree to clear, which limited the spread of agriculture. The oak was known as a barrier between the realm of the humans and that of the land spirits and Gods.

Natural oak groves were honored as a sanctuary for the local land spirits. Trees growing by sources of water, such as over a wells were of particular importance and considered portals to the Spirit world. Shrines were likely built near such places. Later, when these very shrines were converted to Christian churches and magick wells to holy wells, often the oaks were left in peace rather than cut. Time eventually felled the oldest of the oaken groves and few remain. But even the early Celtic Christians recognized the prominence of the oak as a spiritual entity and enveloped it into the new religion.

It is also not insignificant that the Dagda, “the Good God,” sometimes carried the title of Daire, a name meaning “oak” as well as “fruitful one.” The Dagda had an oak harp that would never play without him being present. To get it to play, he would say to the instrument:

Come, oak of two cries!

Come, hand of fourfold music!

Come, summer! Come, winter!

Voice of harps, bellows, and flutes!

The two names for the harp, “Oak of Two Cries” may have meant the oak in flower and the oak in wither. “Hand of Fourfold Music” may have referred to the oak's presence at the four fire festivals marking the four Celtic seasons. The Dagda as the earthen provider held a link to the regeneration of the earth and its bounty through this oaken instrument. In the hands of the Dagda, the oak was a consistent symbol of life. In a myth of the hero Cuchulainn, the antagonists known as the children of Cailitin attack Cuchulainn's fortress with dead oak leaves—not a terribly vile weapon in its own right, but the symbolism of the dead oak leaves evokes images of death and decomposing. A live oak was a blessing. Dead oak may have meant a curse.

In a Welsh myth, the God Gwydion, helped by his brother Amaethon, the God of agriculture, and his son Lleu fought the “Battle of Trees”: a war meant to secure three bounties for man: the dog, the deer, and the lapwing. It was a battle of man against advancing trees. The smallest trees were the easiest to “conquer,” but the oak stood in defense of all of the others. This battle serves as an illustration of humanity's encroachment on the forest, “taming it” for agriculture and settlement building. Yet, the oak was the most difficult to tame. It was the great gatekeeper between the world of men and the world of Gods. The tools of the time were no match for a giant oak's strength and girth. In today's increasingly environmentally sensitive world, it may be hard to celebrate a battle against trees or nature. Yet, at the time these myths and poems took form, nature was still very much a force to fight and tame as humans were still quite vulnerable to it. Oak meant life. Oak meant challenge. Oak was both the provider of health for communities, and also drew a strong line where humanity's realm ended and that of the land spirits began. In that sense, the oak was the land's image of the great land Goddess. For its mighty position, the oak demanded the greatest respect of the Celts and as we will also see, the greatest sacrifice.

The presence of oak in Brigid lore seems inexplicable if the Druidic history is not considered. The world of the ancient Celts was fraught with terrifying things. Appeasing the Gods required immense sacrifice. When a new settlement was founded, a domesticated animal (often a bull or a horse) was often sacrificed and buried in the center of the dwelling to appease the local Spirits, invoking their favor on the burgeoning community. Some animal sacrifice occurred at socio-political-religious festivals, where the animals were consumed as part of a ritual feast. But in some instances . . ., animal sacrifice wasn't considered enough to appease the Gods. The best of the sacrificial offerings was man, and bloody rites in the name of pleasing the Gods were performed in the oak groves of the Druids.

One account of a Druidic oak grove was anything but the romantic or peaceful images commonly seen in paintings or literature. “No birds or beasts dared enter it, and not even the wind, but the branches moved of their own accord and water fell from dark springs.” The frightened writer then described the groves as dark and gloomy, oak branches woven tightly together to block out the sun, and in the center, a series of altars heaped with human remains, with blood deliberately splattered on the surrounding oak trunks. Horrifying heads were carved into the oak stumps to ward off the uninvited. Trees could fall and rise again, phantom flames would appear among the trunks, and serpents glided between them. No humans planning to leave the grove ever entered it, aside from its Priests.

Other stories include the sacrificial victims being nailed to the oaks, the Druids then divining events of the future through the death throes, positions of entrails, and where the blood landed on the grove trunks. These victims might have been shot with arrows or impaled in the shrines and then suspended on the trees, their final movements deciphered as oracles. Some victims were burned alive with oak timber as fuel, as in the legendary Wicker Man. The Gods could not be fully appeased until human life was offered and some have said that the deaths meant the bounty of the harvest. Whatever the method, oak had a role in these rites. Some scribes wrote that the Druids refused to perform their rites if, at the very least, oak leaves were not present. Others wrote that oak wood was the primary fuel for flames in the Druidic shrines.

These stories of sacrifice are undoubtedly nasty, but before anyone runs away screaming, it is important to keep in mind that the Romans had plenty of need for propaganda against the Celts. Roman people historically did not support the destruction of religions shrines, perhaps out of fear of the foreign Gods’ retribution, but likely also out of respect for the shrines, themselves. Politically, it was in Rome's best interests to annihilate the Druidic caste, which would dismantle the core of the Celtic world and therefore make the lands easier to conquer. Portraying Druidic shrines as horrific places of human slaughter would rally support—and possibly more willing tax money—for shrine—and therefore, Druidic—destruction. It may also have been fear. Victims were frequently captured soldiers or community criminals, although they routinely included persons of prestige, willingly giving their lives over to the Gods for the benefit of their communities. It is highly likely that details are exaggerated. Yet human sacrifice was a regularity in religion in most parts of the world at that time in human history. Romans did quite a bit of it themselves. Some Roman writers reported that the Celts only practiced human sacrifice during times of extreme danger or perceived emergency. Toward the end of the sovereign Celtic era, circumstances across the land may have been so stressed and chaos-laced as the Roman occupation increased that it might have inspired more actions as such. While the lurid nature of the tales is possibly overblown, the reality of human sacrifice in the ancient Celtic world was not—nor is the connection between these practices and the oak. The Lindow Man, a sacrificial victim who was preserved in the bogs of England for nearly two thousand years, is one of the more famous archeological discoveries. He was found with traces of mistletoe resin in the stomach of his ancient corpse, confirming the suspicion that the great oaks were connected with great sacrifice.

So, why oak? Why did these trees bear the brunt of Druidic sacrifice? The oak was an embodiment of the spirit of the land—a living face of the Goddess herself. Performing the rites on oak or with oak lumber provided the most direct link for the Druids to make their sacrifices for the land Deities. The Celts may have also recognized the sacrifice the land made naturally for the betterment of the living via the dropping of the oaks’ leaves and acorns. Perhaps in the expansion of agriculture and reaping of iron ore, the Celts were aware of their impact on the environment and believed that only a sacrifice of a human could compare to the sacrifice the earth made. A cryptic phrase derived from these rites describes, “Eyes to the sun, breath to the wind, life force to the atmosphere, ear to the cardinal points, flesh to the earth,” which may speak of dismantling the human body to return it to the Divine source, possibly in a manner consistent with how the Celts saw the land being dismantled for their own use. To use the King of the Trees both as fuel for the rites and as subject of placation showed the Celts'deference to the Gods as well as their determination to surmount any obstacle the Gods could throw. The seemingly immortal nature of the oak may have also played a part. Perhaps the Celts wished to garner some of the ageless quality of the tree for their own people. The questions are complex and deserve their own book. If it suffices to say that oak remained a paramount fixture in the Celtic spiritual lore and its connection to sacrifice an indelible one, its image allows us to understand more about Brigid's relationship to sacrifice as well.

Brigid's myths speak heavily and frequently of her powers over fire and water and completion of important tasks, but oak isn't readily found. In fact, the only tree mentioned in Brigid myths is apple, not oak:

Once a woman had a bounty of apples in her orchard. Not a branch could be found that wasn't bowed with the weight of the plump fruit. A woman gave Brigid a blooming basket of apples, seeking her blessing and praise. Soon after, a pair of hungry and downcast people came to Brigid to ask for food. She immediately gave them the basket of apples, along with a blessing and praise, and sent them on their way. The woman was angry. “I brought these apples for you! Not for those people. Why did you give away my gift?” Brigid smiled and bid the woman goodbye and quietly cursed the tree from which the apples had come. Still angry, the woman walked home to discover an empty orchard. All the apples had fallen from the trees and lay rotten on the ground. The orchard never bloomed again as Brigid saw to its barrenness.

—TRADITIONAL TALE

Despite its absence from her myths, oak surrounds Brigid's image in churches, statues, and in stained glass portraits. Even the name Kildare where Brigid's famed shrine continues to be kept, comes from the name Cill-Dara, literally meaning “Church of the Oak.” At this shrine, the ancient oak mentioned at the start of the chapter survived until nearly the tenth century, when it likely died of natural causes. Like the Glastonbury oaks, it could have easily been a thousand years old, or older. For centuries after the shrine's conversion to a church, the oak stood and its reverence continued in Celtic Christianity. The shrine's perpetual fire is believed to have been fed oak timber as fuel. When Bishop Delany restored the Brigidine order in the nineteenth century (after its Reformation suppression) to help continuity of the Brigidine order, he brought an oak sapling from Kildare to plant at a new Brigidine convent in County Carlow.

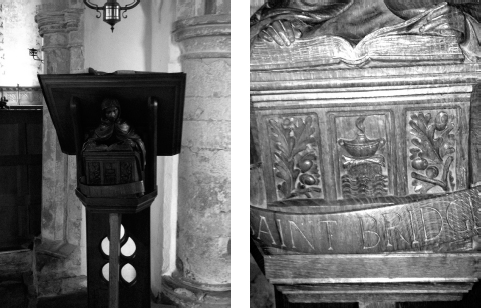

Over the centuries, Brigid has not strayed from her connection to the oak tree. Many of the older churches named for St. Brigid had roofs, slats, and pews made from oak. In some of the Norman-era St. Brigid churches the clergy's vestments are detailed with oak leaves, such as the famous Skenfrith Cope, which is also stored in an oak case. Some of these garments are centuries old. Also at the St. Bridget church at Skenfrith, an image of Brigid hewn completely out of solid oak greets parishioners from the pulpit. In Voudon, some stories suggest that Maman Brigitte lives in an oak tree in the cemetery. Over the last few decades, oak saplings have been planted at St. Brigid's church in Kildare, encouraging the tree to reclaim its rightful place.

Images of St. Brigid, hewn completely out of oak, on the pulpit of the St. Bridget Church in Skenfrith, Monmouthshire.

While the apple tree story does not indicate Brigid's patronage over oak, it does indicate her abilities as a land Goddess. The Goddess of Land can and will give, but will also take away at random. The tree connection reveals her as a fierce protector of the poor, much in the way that the oak was known for being the defender of the smaller, weaker trees as in the mythic battle. The story also illustrates the nature of true sacrifice—giving for the betterment of others, not of the self. The oak's roots are deep and run wide, dropping enough acorns to create a family of trees. If the oak tree was a symbol of the living embodiment of the land, it is natural that it would be connected to a Deity such as Brigid whose living embodiment was the land—including the topography and foliage. It is through her embodiment as the land Goddess that Brigid is connected to oak and it is through oak that she embodies the Sacrificial Goddess.

Reflection: What is the nature of giving unconditionally? Why do we give? Is response in kind expected? Is sacrifice a willing exchange or an assumed one? For what would we be willing to sacrifice and what do we expect in return? Can we even expect a result of sacrifice?

When Brigid was young, her beauty was renowned. But she had promised chastity to the Christian God, who would lay a curse upon any man who tempted her to break her vow. One day a young man caught sight of her walking alongside the road and began to follow her. Fearful for the man's life should he be the cause of Brigid's broken chastity, she hurried away. The man turned and mounted a horse, pursuing her relentlessly through the hills and valleys. Brigid ran faster and ducked beneath a bridge, kneeling by a stream. She plucked out her eyes out to avoid being recognized. The man, horrified by the sight, turned on his horse and fled. Brigid then healed herself in the stream, her eyes renewed, and she continued about her journey.

—TRADITIONAL TALE

This story is an easy sore on contemporary readers. We so often are exposed to horrifying stories of women being punished for the “crime” of being raped or abused by assailants, the idea of a woman literally plucking her own eyes out for the sake of a potential assailant's soul may feel like a thorn in that rightfully painful place. But if we look at this through the lens of Brigid as the Earth Goddess, Brigid is making a sacrifice to ensure the well-being of the earth's inhabitants, like the harvest Goddess Tailtu, who died clearing the forest for the fields to be planted, or Boann, who gave her body to be the river. As the eyes of Celtic sacrificial victims were offered up to the sun, Brigid's plucking them out could be protecting the man from dangers he does not recognize himself, perhaps reminiscent of a sacrifice to the Sun Gods believed to protect the community from the dangers that come from long winters. In the end, like the Earth Goddess she is, Brigid regenerates herself.

Reflection: When have you had to make a sacrifice that others did not understand? Have you had to sacrifice for others, without their even knowing about it or that there was a need to do so in the first place? To what depths would you go to give of yourself, completely, without credit or acknowledgement?

Was Brigid ever the desired recipient of the bloody sacrificial gifts? Or did worship of Brig the Exalted One not require such appeasement? In truth, we'll never know, but in probability, sacrifice happened for Brigid. Even the most comely practices surrounding Brigid, be she saint or Goddess, carry definitive links to a time when the greatest gift to give was that of the human life. Some older rites include the offering of chicken blood at a crossroads at Imbolc. The pattern of the blood on the ground would indicate whether Brigid was displeased, a connection to the rumored practice of Druids watching for signs in the death throes of their victims.

A series of rites known as the Threshold Rites took place for centuries in rural Ireland, honoring Brigid as sacrificial Earth Mother in a subtle way. More comprehensive information can be found in The Rites of Brigid, Goddess and Saint by Seán ó Duinn. In the Threshold Rites, rushes were gathered and bundled on the eve of Imbolc (January 31). Sometimes, the rushes were formally shaped into a human form and wrapped in cloth to look like a dress. If one member of the house had a particularly dangerous line of work, such as fishing, their clothing was often used to dress the doll, further aiding in their protection. The rush bundles were left on the doorstep before the sun set while a supper was prepared inside. When supper was ready, someone (usually the “man of the house”) would go to the step, close the door, and take the bundle of rushes in his arms while reciting something called a threshold dialogue with everyone inside, announcing Brigid's arrival and requesting that she come in. Sometimes, the bundle was carried around the house three times until someone inside called out Cead Failte Romhat, a Bhrid! (roughly, “Brigid Is Very Welcome!”).

Finally, the “woman of the house,” wearing a veil of some sort, opened the door and Brigid, symbolized by the bundle of rushes, was welcomed into the home. The rush bundle was set near the stove and if the dinner were being cooked in a large pot, the pot would be set on top of the bundle. The family then served themselves from the pot. After the supper, the pot was removed and the rushes divided among the family, each person forming them into a St. Brigid's cross. The crosses were often nailed to the beams inside the home for protection. The breaking of Brigid's rush-body, the ritual feast, and the weaving of the dismembered doll into protective amulets was a gentle descendant of the earlier rites, when a human would be the sacrifice. In the Threshold Rite, Brigid was honored as Earth Mother and her sacrifice was recognized and celebrated, and energies of peace and protection invoked against dangers present outside of the home.

Through its recurring image in Brigid iconography and their mutual myth and history connected with sacrifice and protection, oak quietly symbolizes Brigid's identity as the Earth Goddess who gives so that living creatures may flourish. The oak can also be seen as a symbol of Brigid's endurance through time. It is a plant of immense longevity, nearly bordering on immortality. The curious mistletoe is its own testament to Brigid's enduring presence—blossoming after leaving its base, and as Irish descendants took her image around the world. Like mistletoe, she blooms without root.

The oak is an inspiration. Its stillness and strength continue to mystify humans in a largely de-mystified world. At the 9/11 Memorial in New York City, architects planted white oak saplings so that in a number of years, these beautiful trees will shade the area. Oak's ancestry of slow growth yet inevitable strength, and symbolic ability to stand through time is not lost on the contemporary. The reality that a small, fragile nut can find its way to root in any place (I've seen oak grow from bricks and concrete!) can almost seem fantasy. Oak's slow growth shares a commonality with Brigid. An oak grows slowly and takes decades to mature, much like the development of the Bard or the Smith. The oak must sacrifice its leaves and acorns and eventually its own self, its trunk becoming the food and fodder for other plants just as the Bard sacrifices years of their life to their training in hopes that their work will be a platform for subsequent Bards to learn their craft. The time, patience, and endurance of both the oak and the Bard weave into Brigid's ever-expanding cloak of influence. When passing by an oak, stop to say hello as you're also sending good wishes to Brigid as well.

Using oak in your Brigid Magick is a powerful way to connect with her as Earth Mother. It also calls to mind the connection to personal sacrifice. Brigid of Oak asks us to consider what we deem important—for ourselves, for our families, and for our communities. The kind of sacrifice Brigid as Oak and Earth Mother makes should not be confused with martyrdom. The earth gives only what is in its power and resources to give and all earthen resources are finite. When the earth is pushed beyond its capacity to give, it stops or even retaliates. For one example, if a forest is fully felled and cleared, some of the results include landslides that can wipe away hillside homes or other natural areas. Carbon harvested from the earth and burned continues to heat up the atmosphere, and the earth responds by increasing the number of violent storms, which may be a self-regulatory cooling method. The ancient Celts had individuals, willing or not, give the greatest sacrifice of their lives, but we also must keep in mind that such extremes weren't necessary for most people. There may come a time when an individual must sacrifice something that hurts to give, but the risk of not giving is even greater, such as a parent selling a home to pay for their child's surgery. Most sacrifice might mean picking up an extra work shift or working a slightly longer day a couple of times a week, a sacrifice of some leisure time in order to enrich a home's prosperity. Sacrifice doesn't automatically mean taking a full-on second job and sacrificing all sleep, unless the situation was dire enough to call for it. Among my clients, students, fellow members of the community, and even myself, big sacrifices are given all too easily and quickly for things that are insignificant in the long run, but we are reticent to sacrifice for things that matter to us greatly. I am equally guilty of this, and I have no idea why any of us do such nonsense. We might be willing to sacrifice sanity and time and emotional energy on reflecting, ruminating, and verbally disseminating the actions of a rude co-worker or former flame, yet be unwilling to sacrifice time or other resources to help a community cause, even if the sight of a shoeless person in winter hurts our hearts. Regular acts of small sacrifice strengthen the Spirit. They teach us where our boundaries and abilities to give are. Before communing with Brigid's Oak energy, participate in a small act of sacrifice to enter into that energetic understanding.

If you live in an area where oak grows, collecting acorns for your altar or magick space is helpful in connecting you with this side of Brigid. If you happen to live or work with people who are energetically or emotionally draining, carrying three acorns will help fortify you against these influences. (Note: If you are in a situation where you are being outright abused, do not rely on acorns—seek help.) If you are in a position in which you have to sacrifice something important to you, such as a home as in the example above, having acorns present with you will lend strength to your sacrifice and also serve as a reminder that, like the oak who sacrifices acorns that ultimately will lead to a rebirth, so can our initial sacrifice lead to new things.

When you collect the acorns, make sacrifice in honor of the oak when you do it. Many magick practitioners leave hair, saliva, or even blood, or a food or drink offering. Food scraps will ultimately compost and make for new soil, if they're not toxic to local animals. An excellent and simple sacrifice a human can make in honor of oak, or any tree, is collecting trash or volunteering with a parks or forestry department. When writing this chapter, my partner and I spent an afternoon collecting garbage in a park near our apartment. It was indeed a sacrifice of time and stomach stability as the stench of NYC park trash is rarely paralleled by anything, anywhere. After we finished our work, I spent some time with a beautiful young oak slightly off the park's beaten path. I wanted to take some of the acorns strewn on the ground home to my Brigid altar and, while touching the tree's truck, opened my senses to feel if this would be all right. In my head, I heard a resounding, “NO.” I had an image of a mother being separated from her baby and felt a grip of panic. It seemed odd. There were so many acorns lying around that it couldn't hurt the whole forest if I took a couple home. Why did I get such a sensation? I heeded the feeling, however, and did not take the acorns. Later, on doing some more research, I learned that the time of year we'd picked to do this work was when the acorns were more likely to take root than any other time of the year. It made sense as to why the tree did not want the acorns removed.

It may sound bizarre that a tree could share such a message, but keep in mind that a tree is a living thing—most trees are much older than you or I—and a tree has electrical impulses of its own and responds to injury (think of sap rising when a hole in a tree is tapped). It is probably very aware in its own way when a part of itself is in danger. Maybe it was my own head doing the tree-talking and an ancestral part of me knew this was a bad time to take the acorns, or maybe evolution has provided the oak with a vibe of “Get away from my acorns . . . I must regenerate” during the season of the year when regeneration is most likely to happen. It is important to be mindful when performing your sacrifice that you don't assume that the tree owes you its seed. Humans have already taken away a great deal from trees and forests and we're not owed much more. It's not a case for anxiety, but a suggestion to stop, feel, and trust your instincts. Your own instincts may tell you the collection of wood or acorns is perfectly justified, and in that case, you are probably right. If you don't live in an area where oak grows, consider the qualities of the tree—slow growing, old, shedding, and renewing, and work with the energies of a similar tree in your area.

Before taking your acorns or oak, spend time with the tree and see if this is what is right for it. (I encourage taking from branches or limbs that have fallen. It isn't necessary to cut a living tree unless it's in danger of falling and injuring someone.) If you feel that it is right for the tree to take something from it, a suggested recitation is as follows:

Brigid of the Oaken Grove,

My sacrifice please now behold,

I seek protection, strength, and life,

Oak bar the door from pain and fright.

Do your work, be it collecting trash or another method. The simple act of sacrifice may open the door for greater sacrifices that you are able to make outside of the forest. If the timing seems wrong to collect wood or seed, try again at another time.

The following meditation is designed to explore personal sacrifices in exchange for manifestation of deeper desires, one's own Will, and identifying sacrifices necessary to make it happen.

Sit quietly with closed eyes and even breathing. Acknowledge the sounds you hear or thoughts that flow through your mind. Try not to fight or follow them. Imagine the dark behind your eyes is a black mist. Imagine you stand on a soft path. Although you cannot see, allow yourself to trust in the dark and to walk forward. You carry a small bag. In time, the mists begin to thin. The full moon and stars begin to appear in the sky above you. You are in a forest. Shortly, you will begin to hear the sound of water, but it is not the ocean. You can hear waves gently lapping against land.

In the distance, you can see the moon's reflection on the water. As the trees thin further, you find yourself at the edge of a great lake. There is just enough light to reveal your reflection on the surface. Sit with your image for a moment.

The waves startle. A boat approaches and gently scrapes against the shore. If the boat seems sturdy enough, climb aboard. The vessel pulls away from the land and heads across the water for the land on the other side, just barely in your sight. The mists have fully settled and the stars shine bright. The land ahead contains a flickering orange dot, passing in and out of sight. As your boat approaches the land, you see that it also is covered with forest, even thicker than before. In the distance, you can hear the sound of a flute playing.

The boat reaches the shore at last and you step out onto land, covered with dried leaves. Clutching your bag, you begin to walk across this new shore, the leaves crunching loudly beneath your feet. Two gallant trees mark a clearing in the forest. Begin walking toward them. Acorns litter the ground as the leaves turn to soil. You recognize the two trees as majestic oak. Pass between them and continue on the path, which gently rises. Past these two trees, you pass another two oaks, larger than the first. In passing those, you pass two more even larger than before, and then two more. The trees create a canopy of rustling leaves above your head. You feel acorns crackle beneath your feet as these ancient trees direct a path through the forest. Continue to walk uphill.

In time, the path will turn gently to your left and continue to rise. The oaks have become enormous, their limbs bowing toward the ground, but their tops so tall they vanish into the night sky. The flickering orange has reappeared. The path between the trees grows wider.

Eventually, the oaks give way to a massive clearing. In the center, a giant fire roars. The clearing is ringed by the largest oaks you have ever seen, their top branches knitted together and their limbs entangled so that you are completely surrounded by tree and leaf. Each trunk has a face all to its own, carved into the trunk. You enter the clearing, still clutching your bag.

Standing by the fire are two figures dressed in fur and hide. A third figure, covered from head to toe in a cloak of fur, stands facing the fire.

This figure turns—it is a woman. The fire behind her creates shadow and you cannot see her face, but only her eyes.

She leads you around the fire. Behind it is an altar. At this time, share with the woman your true Will. What is your true Will? What is it you desire most? Speak your truest Will and do not lie—she will know.

If you are able to articulate your truest Will, tell her then what you are willing to sacrifice to see this Will come to manifest.

Open the bag and inspect what is inside. Decide if you are willing to lay these on the altar, for these things will be sacrificed for your Will to manifest. Are you willing to lay them down?

Then, the woman takes you by the hands and lays you on the altar. Stretched out with the stone slab beneath you and the stars above you, the roaring fires to your side, the woman asks you a question. Answer honestly.

Be present with her as she does her work.

When the work has completed, thank her for any messages, assistance, or otherwise. You exit the circle, traveling back down the path through the oak avenue to the boat. You travel back across the water to the place where you started. The stars fade, the darkness once again becomes the blackness behind your eyes. When you feel you are settled back in your present world once more, open your eyes. Record thoughts in a journal.

Ideally, this meditation would be performed on a full moon and the subsequent ritual performed six days after the following new moon. Some important areas to note include your reflection on the water. It may indicate your soul's current image, although some who do this meditation report it being difficult to see an image. This may happen during a time of change or transformation, or it simply may not be something your mind is in need of grasping. The motion on the water can be indicative of the emotional state: stormy, still, murky, bubbly. If at any point the boat is not seaworthy or if the path is too difficult or even unavailable, it might be best to try the exercise again later. Note also the animal fur. As in the exercise at the start of the book, this may indicate a power animal.

The following ritual can be performed immediately following the meditation. Doing them in tandem will increase the experience for both.

Romans wrote that the Druids collected mistletoe on the sixth day following a new moon, cutting the mistletoe from its oak host with a golden sickle. Mistletoe and its miraculous qualities of growth without root often required a sacrifice of importance such as a bull or a human. The herb was considered all-healing, one of the few to keep its berries in winter, and for that reason was believed to cure infertility. Kissing under mistletoe is believed to have derived from this belief. Mistletoe is a good herb to use in personal or group rites requiring sacrifice. It grows directly out of the oak, but despite its seemingly parasitic nature, it is a bedrock of stability for ecosystems, being a primary source of food for animals, and birds in particular. Mistletoe is, however, poisonous to humans and should be used symbolically, never ingested.

Gather the following supplies and perform this rite on the sixth day after a new moon. Due to the need for mistletoe, this rite will most likely be easiest to do during the Christmas season. This ritual is designed for a group, hopefully with at least one person who can drum. It can be performed alone, but you may want to have a recording of a drumbeat playing for extra emphasis.

Sprigs of mistletoe, one for each person in the rite.

Three red candles.

Brigid oil (see Chapter 10).

A decadent treat and tasty drink. Must be something all parties can agree upon and consume.

Prior to the ritual, perhaps by doing the previous meditation, examine what is blocked. The need for sacrifice does not come from a vacuum. Participants should then write or draw on paper or construct a symbolic image of the habit or thing requiring sacrifice.

Place the red candles and the sprigs of mistletoe on a small table or altar in the center of your working area and cast sacred space in a method familiar to your practices. (See Chapter 10 for a suggested invocation of using Brigid to cast a sacred circle.) Participants should stand outside of the working space.

Once the sacred space has been set, begin the drumbeat and raise energy with the chant: Brig is come, Brig is welcome . . . Brig is come, Brig is welcome. As the chant continues, one person should approach the space and call out, “O, Oak of Seven Cries! Open the door! O, Oak of Seven Cries! Summon the Brig! O, Oak of Seven Cries! Clear the avenue for the sacrifice is now to begin!” (If you are doing this rite solo, chant until the energy has been raised, and then stop and petition the oak yourself.)

When the energy has risen to a prickly point, each participant should proceed—one at a time—into the sacred space, carrying the paper or effigy of their sacrifice. Each will approach the altar, introducing themselves aloud and announcing their true Will (e.g., “I am Brian! My Will is for a promotion at my job!”). The participant should then anoint himself or herself with the oil, and then step aside for the next person to approach.

After all participants have approached the altar and anointed themselves, the announcing of sacrifice begins. One at a time, each person announces his or her sacrifice. Examples might be: “I sacrifice my time on social media so as to dedicate myself to my best performance at work.” “I sacrifice a portion of my salary to charity so that I may give more and heal my heart that suffers.” “I sacrifice some gym time so that I may be more helpful at home and improve my marriage.” “I sacrifice one night of social outings per week so that I may have more time to rest and focus on me.” After all have been declared, whittle each sacrifice down to one or two words and, taking turns, speak the thing that needs sacrifice: “Social media.” “Salary portion.” “Gym time.” “Social outings.” Repeat several times, going faster through each round until the energy again has reached a peak point. You may want to experiment with volume levels, if your area allows. If you are doing this work alone, state your sacrifice and immediately transition into the one or two word description.

Some groups may opt to continue chanting for this next section, and some may wish to go silent. Each member takes up their paper and a sprig of mistletoe and, in unison, stabs through the paper with the stem of the plant. Set all papers and mistletoe back on the altar space and leave while the candles burn down. Share the decadent treats and drinks and, if willing, share experiences or thoughts. If doing this work alone, now is the time for reflection and journaling.

Release the sacred space, giving thanks to Brigid and the Spirit of the Oak.

After the rite, participants may want to place their mistletoe sprigs, still through the paper, in their personal ritual space or in another prominent area to be mindful of what they've given up in order for their Will to manifest.