IN THIS CHAPTER

Differentiating between appetite and hunger

Understanding body signals and hunger cycles

Explaining how health and lifestyle affect appetite

Looking at common eating disorders

Because you need food to live, your body has multiple ways of letting you know that it’s ready for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and maybe a few snacks in between. This chapter explains the signals that send you to the kitchen, your favorite fast-food joint, or that pernicious vending machine down the hall.

Underlining the Difference between Hunger and Appetite

People eat for two basic reasons. The first is hunger; the second is appetite. Hunger and appetite are not synonyms. In fact, hunger and appetite are entirely different processes.

Hunger is the need for food. It is

- A physical reaction that includes chemical changes in your body related to a naturally low level of glucose in your blood several hours after eating

- An instinctive, protective mechanism that makes sure your body gets the fuel it requires to function

Appetite is the desire for food. It is

- A sensory or psychological reaction (looks good! smells good!) that stimulates an involuntary physiological response (salivation, stomach contractions)

- A conditioned response to food (see the nearby sidebar on Pavlov’s dogs)

The practical difference between hunger and appetite is this: When you’re hungry, you eat one hot dog. After that, your appetite may lead you to eat two more hot dogs just because they look appealing or taste good.

In other words, appetite is the basis for the familiar saying: “Your eyes are bigger than your stomach.” Not to mention the well-known advertising slogan: “Bet you can’t eat just one.” Hey, like Pavlov (see that sidebar again), these guys know their customers.

Refueling: The Cycle of Hunger and Satiety

Your body does its best to create cycles of activity that parallel a 24-hour day. Like sleep, hunger occurs at pretty regular intervals, although your lifestyle may make it difficult to follow this natural pattern.

Recognizing hunger

The clearest signals that your body wants food, right now, are physical reactions from your stomach. An empty one has absolutely no manners. If you don’t fill it right away, it will issue an audible, sometimes embarrassing, call for food, the rumble called a hunger pang.

Hunger pangs are muscle contractions. When your stomach is full, these contractions and their continual waves down the entire length of the intestine — known as peristalsis — move food through your digestive tract (see Chapter 2 for more about digestion). When your stomach is empty, the contractions just squeeze air, and that makes noise.

This phenomenon was first observed in 1912 by an American physiologist named Walter B. Cannon. (Cannon? Rumble? Could you make this up?) Cannon convinced a fellow researcher to swallow a small balloon attached to a thin tube connected to a pressure-sensitive machine. Then Cannon inflated and deflated the balloon to simulate the sensation of a full or empty stomach. Measuring the pressure and frequency of his volunteer’s stomach contractions, Cannon discovered that the contractions were strongest and occurred most frequently when the balloon was deflated and the stomach empty. Cannon drew the obvious conclusion: When your stomach is empty, you feel hungry.

This phenomenon was first observed in 1912 by an American physiologist named Walter B. Cannon. (Cannon? Rumble? Could you make this up?) Cannon convinced a fellow researcher to swallow a small balloon attached to a thin tube connected to a pressure-sensitive machine. Then Cannon inflated and deflated the balloon to simulate the sensation of a full or empty stomach. Measuring the pressure and frequency of his volunteer’s stomach contractions, Cannon discovered that the contractions were strongest and occurred most frequently when the balloon was deflated and the stomach empty. Cannon drew the obvious conclusion: When your stomach is empty, you feel hungry.

Identifying the hormones that say, “I’m hungry” and “I’m full”

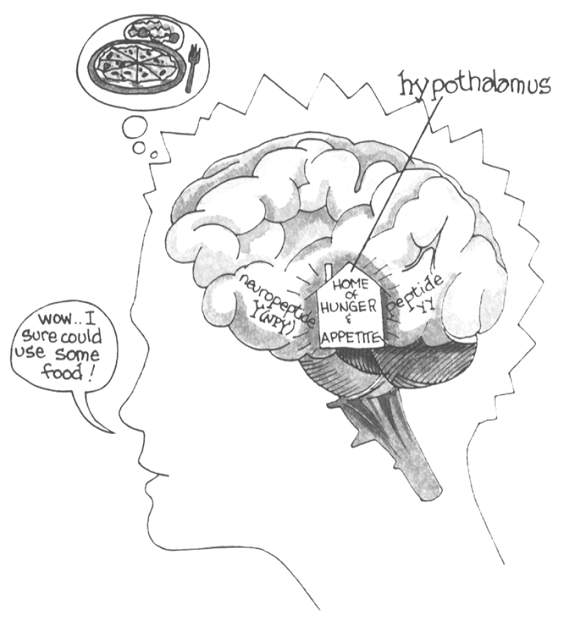

Like so many other body functions, hunger is influenced by hormones — in this case, ghrelin, insulin, PYY (peptide tyrosine-tyrosine), and leptin. These natural chemicals act on the satiety center in your brain (see Figure 14-1) to make sure you get enough to eat — and (perhaps) know when to stop.

- Ghrelin: Ghrelin (pronounced grel-in) is a hormone secreted primarily by cells in the lining of the stomach; smaller amounts are secreted by the hypothalamus. Ghrelin is an appetite stimulant that elicits messages from your brain that say, “I’m hungry.” If you’re fasting or simply cutting back on food to lose weight, your body responds by producing more than normal amounts of ghrelin, triggering a higher than normal desire to eat. This is one way to explain why dieters find it difficult to stick to a reduced-calorie regimen.

- Insulin: Every time you eat, your pancreas secretes insulin, a hormone that enables you to transform the food you eat into glucose, the simple sugar on which the body runs, and then to move the glucose into body cells. The higher level of insulin temporarily suppresses appetite, but when the amount of glucose circulating in your blood declines again, you may feel empty, which prompts you to eat. Most people experience the natural rise and fall of glucose — and the consequent secretion of insulin — as a relatively smooth pattern that lasts about four hours. Note: People with Type 1 (insulin dependent) diabetes don’t produce the insulin needed to process glucose, so the glucose continues to circulate around the body and is eventually excreted in sugary urine.

- PYY (peptide tyrosine-tyrosine): After you’ve eaten, this hormone, secreted by your small intestine and in lesser amounts by cells in other parts of your digestive tract, acts as an appetite suppressant that cancels out ghrelin’s appetite-stimulating effects. Some overweight or obese people seem to have an inability to receive PYY’s message, which is, “You’re full; stop eating.”

- Leptin: Leptin, identified in 1995 at Rockefeller University in New York, is produced in the body’s fat cells, a source of stored energy. Leptin is an appetite suppressant; if your body loses a lot of fat, you also lose leptin. The result? An increase in the desire for food to increase your store of body fat.

Beating the four-hour hungries

Throughout the world, the cycle of hunger (glucose and insulin rising and falling as described in the preceding section) prompts a feeding schedule that generally provides four meals during the day: breakfast, lunch, a mid-afternoon snack, and supper.

In the United States, a three-meal-a-day culture forces people to fight this natural eating pattern by going without food from lunch at around noon to supper at 6 p.m. or later. The unpleasant result is that when glucose levels go south around 4 p.m. (and people in other countries are enjoying afternoon tea), many Americans get really testy, growl at their coworkers, make mistakes they’ll have to correct the next day, or try to satisfy their natural hunger by grabbing the nearest food, usually a high-fat, high-calorie snack. (For a list of calorie-acceptable mid-afternoon snacks, see Chapter 18.)

The better way: Five or six small meals

In 1989, David Jenkins, MD, PhD, and Tom Wolever, MD, PhD, of the University of Toronto, set up a “nibbling study” designed to test the idea that if you even out digestion — by eating several small meals rather than three big ones — you can spread out insulin secretion and keep the amount of glucose in your blood on an even keel all day long.

The theory turned out to be right. People who ate five or six small meals rather than three big ones felt better and experienced an extra bonus: lower cholesterol levels. After two weeks of nibbling, the people in the Jenkins-Wolever study showed that people on the multi-meal regimen had lower levels of cholesterol and lost more weight than people who ate exactly the same amount of food divided into three big meals. (For more on lipoproteins and cholesterol levels, check out Chapter 7. For more on weight control, see Chapter 4.) As a result, some diets designed to help you lose weight now emphasize a daily regimen of several small meals rather than the basic big three. To be fair about it, though, several studies show no beneficial effect, so this is an if-it-works-for-you-do-it issue.

In 2015, scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, California, added another wrinkle: Nibble or gorge, eating within an 8-hour or 12-hour window makes for better bodies. At least in mice. When the researchers allowed their animals to eat anything they wanted but only in a specific 8- or 12-hour window, the mice stayed slimmer and sleeker than their brothers and sisters on the same amount of calories that were allowed to eat throughout the 24-hour day.

Now, most people know they should be sleeping 7 to 8 hours a night. That leaves 16 to 17 hours of wake-time for eating. Set a time limit, say breakfast at 8 a.m. and last snack at 8 p.m., or an hour later in the morning and an hour earlier at night on the 8-hour regimen.

Now, most people know they should be sleeping 7 to 8 hours a night. That leaves 16 to 17 hours of wake-time for eating. Set a time limit, say breakfast at 8 a.m. and last snack at 8 p.m., or an hour later in the morning and an hour earlier at night on the 8-hour regimen.

Maintaining a healthy appetite

The best way to deal with hunger and appetite is to recognize and follow your body’s natural cues.

The best way to deal with hunger and appetite is to recognize and follow your body’s natural cues.

If you’re hungry, eat — in reasonable amounts that support a realistic weight. And remember: Nobody’s perfect. Make one day’s indulgence guilt-free by reducing your calorie intake proportionately over the next few days.

A little give here, a little take there, and you’ll stay on target overall.

Responding to Your Environment on a Gut Level

Your physical and psychological environments definitely affect appetite and hunger, sometimes leading you to eat more than normal, sometimes less.

Baby, it’s cold outside

Think of the foods that tempt you in winter — stews, roasts, thick soups — versus those you find pleasing on a simmering summer day — salads, chilled fruit, simple sandwiches.

This difference is no accident. Food gives you calories. Calories keep you warm. Yes, you will need more energy if you’re running a marathon in the summer than if you’re sitting quietly all day in front of the TV while the snow piles up outside.

But as a general rule, to get the energy it needs to keep you warm, your body will say, “I’m hungry,” more frequently when it’s cold outside. In addition, you process food faster in a cold environment. Your stomach empties more quickly as food speeds along through the digestive tract, which means those old hunger pangs show up sooner than expected so you eat more and stay warmer.

Exercising more than your mouth

Everybody knows that working out gives you a big appetite, right? Well, everybody’s wrong. People who exercise regularly are definitely likely to have a healthy (read: normal) appetite, but they’re rarely hungry immediately after exercising because

- Exercise pulls stored energy — glucose and fat — out of body tissues, so your glucose levels stay steady and you don’t feel hungry.

-

Exercise slows the passage of food through the digestive tract. Your stomach empties more slowly, and you feel fuller longer.

Caution: If you eat a heavy meal right before heading for the gym or the stationary bike in your bedroom, the food sitting in your stomach may make you feel stuffed. Sometimes, you may develop cramps or — as Ken DeVault, MD, and I explain in Heartburn & Reflux For Dummies (Wiley) — heartburn.

- Exercise (including mental exertion) reduces anxiety. For some people, that means less desire to reach for a snack.

Taking medicine that changes your appetite

Some drugs affect your appetite, leading you to eat more (or less) than usual. This side effect is rarely mentioned when doctors hand out prescriptions, perhaps because it isn’t life-threatening and usually disappears when you stop taking the drug or simply because your doctor doesn’t know about it. Some examples of appetite uppers are certain antidepressants, antihistamines (allergy pills), diuretics (drugs that make you urinate more frequently), steroids (drugs that fight inflammation), and tranquilizers (calming drugs). Medicines that may reduce your appetite include some antibiotics, anticancer drugs, antiseizure drugs, blood pressure medications, and cholesterol-lowering drugs.

Not every drug in a particular class of drugs has the same effect on appetite. For example, the antidepressant drug amitriptyline (Elavil) increases your appetite while fluoxetine (Prozac) may either increase or decrease your desire for food.

Not every drug in a particular class of drugs has the same effect on appetite. For example, the antidepressant drug amitriptyline (Elavil) increases your appetite while fluoxetine (Prozac) may either increase or decrease your desire for food.

Revealing Unhealthy Relationships with Food

This chapter, as the title says, is about why you eat when you eat. Up until this point, the reasons have been physiological: Your hormones say you’re hungry or full, or perhaps the weather says you need more food (or less) for energy. But sometimes, the decision to eat or not eat is triggered by an eating disorder, a psychological illness that leads you to eat either too much or too little or to regard food as your enemy or your savior.

Indulging in a hot fudge sundae or two once in a while isn’t an eating disorder. Neither is dieting for three weeks so you can fit into last year’s dress this New Year’s Eve. Nor is the determination to eat a healthful diet. The difference between these behaviors and an eating disorder is that these are medically acceptable while eating disorders are potentially life-threatening illnesses that require immediate medical attention.

For some people, food is not simply a meal. It is the object of love or loathing, a way to relieve anxiety or an anxiety provoker. As a result, human beings may experience various eating disorders — obesity, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and binge eating — which I describe in the following sections.

Eating disorders are serious, potentially life-threatening conditions. If you (or someone you know) experience any of the signs and symptoms described in the following sections, the safest course is to seek immediate medical advice and treatment. For more info about eating conditions, contact the National Eating Disorders Association, 165 West 46th Street, Suite 402, New York, NY 10036; national helpline 1-800-931-2237; website

Eating disorders are serious, potentially life-threatening conditions. If you (or someone you know) experience any of the signs and symptoms described in the following sections, the safest course is to seek immediate medical advice and treatment. For more info about eating conditions, contact the National Eating Disorders Association, 165 West 46th Street, Suite 402, New York, NY 10036; national helpline 1-800-931-2237; website www.nationaleatingdisorders.org.

Obesity

Although everyone knows that there’s a worldwide increase in obesity (spelled out in Chapter 4), not everyone who is larger or heavier than the current ideal body has an eating disorder. Human bodies come in many different sizes, and some healthy people are just naturally larger or heavier than others. But an eating disorder may be present when

- A person continually confuses the desire for food (appetite) with the need for food (hunger)

- A person who has access to a normal diet experiences psychological distress when denied food

- A person uses food to relieve anxiety provoked by what he or she considers a scary situation — a new job, a party, ordinary criticism, or a deadline

Traditionally, doctors find it difficult to treat obesity, but in recent years, some studies have suggested that some people overeat in response to irregularities in the production of chemicals that regulate satiety (the feeling of fullness). This research may open the path to new kinds of drugs that can control extreme appetite, thus reducing the incidence of obesity-related disorders, such as arthritis, diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease.

Anorexia nervosa

Anorexia is voluntary starvation. As you may expect, anorexia is virtually unknown in places where food is hard to come by. Instead, this condition is often considered an affliction of affluence, most likely to strike the young and well-to-do, men as well as women, although more commonly women.

The signs of anorexia are weight less than 85 percent of the normal weight, a fear of gaining weight, an obsession with one’s appearance, and the belief that one is fat regardless of the true weight. For young women, anorexia can lead to the absence of menstrual cycles.

The signs of anorexia are weight less than 85 percent of the normal weight, a fear of gaining weight, an obsession with one’s appearance, and the belief that one is fat regardless of the true weight. For young women, anorexia can lead to the absence of menstrual cycles.

Up to 40 percent of people with anorexia develop bulimia nervosa; up to 30 percent develop binge eating disorder, the next two problems in this section. Left untreated, anorexia nervosa may be fatal.

Bulimia nervosa

Unlike people with anorexia, individuals with bulimia don’t refuse to eat, but they don’t want to hold on to the food they’ve consumed. They may use laxatives to increase defecation, or they may simply retire to the bathroom after eating to take emetics (drugs that induce vomiting) or stick their fingers into their throats to make themselves throw up. Like anorexics, bulimics may develop binge eating disorder.

Either way, danger looms. Repeated regurgitation can severely irritate or even tear through the lining of the esophagus (throat). Acidic stomach contents also damage teeth, which is why dentists are often the first medical personnel to identify a bulimic. Finally, the continued use of emetics may result in a life-threatening loss of potassium that triggers irregular heartbeat or heart failure.

Binge eating disorder

The criterion for a diagnosis of binge eating disorder is consuming enormous amounts of food — a whole chicken, several pints of ice cream, an entire loaf of bread — in one sitting twice a week for up to six months. Some binge eaters become overweight; others stay slim by regurgitating. Either way, binge eating, like other eating disorders, is hazardous behavior.

Binge eaters who regurgitate experience adverse effects similar to those associated with bulimia. Binge eaters who don’t regurgitate risk not only obesity but also, paradoxically, malnutrition. Why? Because the foods they choose may be high in calories but low in vital nutrients. (Think hot fudge sundae again, and again, and again.) More dramatically, the enormous quantities of food they consume may dilate or even rupture the stomach or esophagus, a potentially fatal medical emergency.

This phenomenon was first observed in 1912 by an American physiologist named Walter B. Cannon. (Cannon? Rumble? Could you make this up?) Cannon convinced a fellow researcher to swallow a small balloon attached to a thin tube connected to a pressure-sensitive machine. Then Cannon inflated and deflated the balloon to simulate the sensation of a full or empty stomach. Measuring the pressure and frequency of his volunteer’s stomach contractions, Cannon discovered that the contractions were strongest and occurred most frequently when the balloon was deflated and the stomach empty. Cannon drew the obvious conclusion: When your stomach is empty, you feel hungry.

This phenomenon was first observed in 1912 by an American physiologist named Walter B. Cannon. (Cannon? Rumble? Could you make this up?) Cannon convinced a fellow researcher to swallow a small balloon attached to a thin tube connected to a pressure-sensitive machine. Then Cannon inflated and deflated the balloon to simulate the sensation of a full or empty stomach. Measuring the pressure and frequency of his volunteer’s stomach contractions, Cannon discovered that the contractions were strongest and occurred most frequently when the balloon was deflated and the stomach empty. Cannon drew the obvious conclusion: When your stomach is empty, you feel hungry. Now, most people know they should be sleeping 7 to 8 hours a night. That leaves 16 to 17 hours of wake-time for eating. Set a time limit, say breakfast at 8 a.m. and last snack at 8 p.m., or an hour later in the morning and an hour earlier at night on the 8-hour regimen.

Now, most people know they should be sleeping 7 to 8 hours a night. That leaves 16 to 17 hours of wake-time for eating. Set a time limit, say breakfast at 8 a.m. and last snack at 8 p.m., or an hour later in the morning and an hour earlier at night on the 8-hour regimen. Not every drug in a particular class of drugs has the same effect on appetite. For example, the antidepressant drug amitriptyline (Elavil) increases your appetite while fluoxetine (Prozac) may either increase or decrease your desire for food.

Not every drug in a particular class of drugs has the same effect on appetite. For example, the antidepressant drug amitriptyline (Elavil) increases your appetite while fluoxetine (Prozac) may either increase or decrease your desire for food.