Chapter 17

Choosing Wisely with Pyramids, Plates, and Labels

IN THIS CHAPTER

Evaluating nutritious diet diagrams

Reading the Nutrition Facts Labels

Putting Nutrition Facts to work for you

This chapter is devoted to pictures of pyramids, plates, and labels, all designed to serve as a kind of building blocks for grown-ups. Instead of letters in the alphabet, these blocks represent food groups you can put together in various ways to create the structure of a healthful diet.

Choose one, take notes, follow directions, and then choose another, create a different pattern, and so on. Any way you play, your reward is likely to be a better body.

Checking Out Basic Diet Pictures

The essential message of all good guides to healthful food choices is that no one food is either good or bad — how much and how often you eat a food is what counts. The food pictures, therefore, come with three important messages:

- Variety: The fact that each contains or describes several different foods tells you that no single food gives you all the nutrients you need.

- Moderation: Having one group drawn smaller than others on a food pyramid or dinner plate or showing clearly that there is less of one group recommended, as on the Nutrition Facts Label, tells you that although every food is valuable, some — such as fats and sweets — are best consumed in small amounts.

- Balance: You can’t build a diet with a set of identical blocks. Blocks of different sizes show that a healthful diet is balanced: the right amount from each food group.

Clearly, food pyramids, plate pictures, and labels make it possible for you to eat practically everything you like — as long as you follow the recommendations on how much and how frequently (or infrequently) to eat it.

The original USDA Food Guide Pyramid

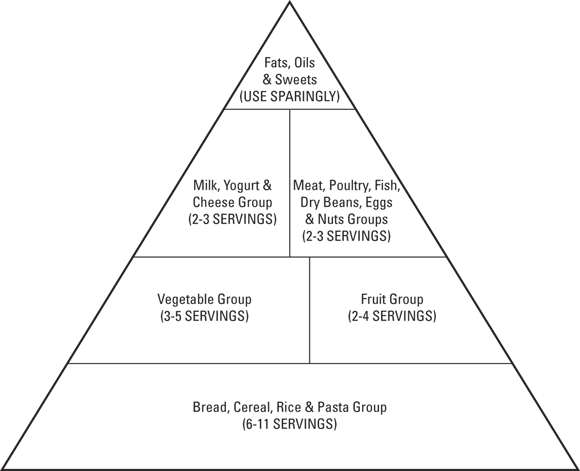

The first food pyramid was created by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 1992 in response to criticism that the previous government guide to food choices — the Four Food Group Plan (vegetables and fruits, breads and cereals, milk and milk products, meat and meat alternatives) — was too heavily weighted toward high-fat, high-cholesterol foods from animals.

Figure 17-1 depicts the original USDA Food Guide Pyramid. As you can see, this pyramid is based on daily food choices, showing you which foods are in what groups. Unlike the Four Food Group Plan, the pyramid separates fruits and vegetables into two distinct groups and lists the number of servings from each food group that you should have each day. (The number of servings is provided in ranges. The lower end is for people who consume about 1,600 calories a day, and the upper end is for people whose daily dietary intake nears 3,000 calories.)

From pyramid to plate: The evolution of the Food Guide

You may think that after the government came up with this apparently sensible way to decide what’s good to eat, everyone in the nutrition establishment would stand up as one to shout, “Huzzah!” You’d be wrong. The complaints began practically the minute the pyramid hit the street, so to speak.

On the one hand, critics said the pyramid was indecisive, lumping all fats — good, bad, and in-between — into one category and failing to distinguish between whole grains (good) and refined grains (not great). On the other hand, critics said the advice was decisive but in the wrong direction — for example, by allowing more red meat than considered optimal by the real (or at least the emerging) science. And everybody asked, “How come there’s no picture or sentence to tell us to exercise every day to control our weight?”

What to do? Nutritional acrobatics. In 2005, the USDA released a new Food Guide Pyramid, which was actually the first pyramid turned sideways. This version of the pyramid had the following:

- Unlabeled sections representing the foods in your daily diet, each identified by color: orange for grains, green for vegetables, red for fruits, yellow for oils, blue for milk, and purple for meat and beans

- An admonition to eat “lots of different kinds of foods to build a better diet” but no specific servings-per-day recommendations for any food group

- Directions on how to key certain data into a form to find out how many servings of each food group you should eat based on your age, sex, and level of activity but not — to everyone’s surprise — your height and weight

- Steps, actual steps, with a teensy gender-neutral human being climbing up the side of the pyramid to signify (1) physical activity, and (2) the fact that you don’t have to leap tall buildings in a single bound like Superman (or woman) to improve your nutrition because even small steps can make a big difference

All these things may have been new — but improved? Not so much.

Call me foolish. Call me old-fashioned. Call me a fan of the simplest solution, which, it seems, is no longer a pyramid. In May 2011, the USDA introduced the newest new thing, a plate that shows (sort of) how much of each type of food you should be consuming. It includes more veggies and fewer meats. So now you can go to the USDA website at www.choosemyplate.gov to see the latest version of the Totally Official Food Guide Pyramid — sorry, Plate.

Or you can check one of the diagrams from the loyal oppositions in the next section.

An assortment of pyramids and plates

Government documents, including food guides, are often one-size-fits-all — meaning they may not fit you.

Are you a fan of Asian food? Do you like your menu with a Central or South American accent? Does meat turn you off? If you answer yes to any of these questions, there’s a special food pyramid waiting for you. The Oldways Preservation trust, a Boston-based internationally known nonprofit organization devoted to improving people’s diet with “positive programs grounded in science, traditions, and delicious foods and drink,” has created a number of pyramids based on ethnic food plans, perhaps the best known being the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid. The following Oldways pyramids are a guide to good food in various languages. To see them, go to http://oldwayspt.org/resources/heritage-pyramids and choose what pleases you.

Note that if you prefer plates to pyramids, the Oldways website is pleased to offer various adaptations just for your dinner table.

The Asian Diet Pyramid and Plate

Oldways’s partners for this pyramid, introduced at the International Conference on the Diets of Asia in San Francisco in 1995, were the Cornell-China-Oxford Project on Nutrition, Health, and Environment and the Harvard School of Public Health. This pyramid codifies a primarily vegetarian diet historically linked to the generally low incidence of cardiovascular disease in Asian countries.

The Vegetarian Diet Pyramid and Plate

This pyramid, created by Oldways and the Harvard School of Public Health, was released at the International Conference on Vegetarian Diets in Austin, Texas, in 1997. It’s a traditional vegetarian plan with fruits, vegetables, grains, and dairy products but no meat, fish, or poultry. It’s described as promoting “agricultural sustainability.” Translation: Producing these foods takes up and thus wastes less use of natural resources — land, fuel, and water — than modern industrial food production. Good for you; good for the planet.

The Traditional Mediterranean Diet Pyramid and Plate

Oldways and the Harvard School of Public Health released the first Mediterranean Diet Pyramid in 1993; this updated version appeared in 2009. As you can see, it has lots of fruits and veggies, poultry and lean red meat, olive oil, cheese, and yogurt — all accompanied by moderate amounts of wine. In short, the traditional diet of, yes, the Mediterranean countries circa 1960 when, Oldways explains, “The rates of chronic disease were among the lowest in the world, and adult life expectancy was among the highest, even though medical services were limited.” Tastes good, too.

The Latin American Diet Pyramid and Plate

Oldways introduce this pyramid in 1996 at the Latin American Diet Conference in El Paso, Texas; the updated version appeared in 2009. The food plan in this pyramid is based on the traditional and modern-day diet of Central and South America, which Oldways describes as a melding of three distinct cultures: the indigenous Aztecs, Incas, and Maya; the 16th century Spanish explorer; and the Africans brought in first as slaves. The mixture produced a rich blend of local fruit (agave, avocado), vegetables (cassava, chayote), grains (amaranth, maize, quinoa), poultry, and meat (goat), once again accompanied by moderate amounts of alcohol. Plus exercise, of course.

African Heritage Diet Pyramid and Plate

In 2012, Oldways debuted the latest addition to its list of diet pyramids and plates, this one based on the fresh plant foods, healthy oils, homemade sauces and marinades of herbs and spices, fish, eggs, poultry, yogurt, and minimal consumption of meats and sweets common to the diets of African origin now common in places ranging from North and South America to the Caribbean and, of course, in Africa itself.

Understanding the Nutrition Facts Labels

Once upon a time, the only reliable consumer information on a food label was the name of the food inside. The 1990 Nutrition Labeling and Education Act changed that forever with a spiffy new set of consumer-friendly food labels that include

- A mini-nutrition guide that shows the food’s nutrient content and evaluates its place in a balanced diet

- Accurate ingredient listings, with all ingredients listed in order of their weight in the original recipe — for example, the most prominent ingredient in a loaf of bread is flour

- Clear identification of ingredients previously listed simply as colorings and sweeteners

- Scientifically reliable information about the relationship between specific foods and specific chronic health conditions, such as heart disease and cancer

The Nutrition Facts Label is required by law for more than 90 percent of all processed, packaged foods — everything from canned soup to fresh pasteurized orange juice. Food sold in really small packages — a pack of gum, for example — can omit the Nutrition Facts Label but must carry a telephone number or address so an inquisitive consumer (you) can call or write for the information.

Just about the only processed foods exempted from the nutrition labeling regulations are those with no appreciable amounts of nutrients or those whose content varies from batch to batch or those from very small food processors, such as the following items:

- Plain (unflavored) coffee and tea

- Some spices and flavorings

- Deli and bakery items prepared fresh in the store where they’re sold directly to the consumer

- Food produced by small companies

- Food sold in restaurants, unless it makes a nutrition content or health claim (Want to know how to eat well when eating out? Check out Chapter 18.)

Labels are voluntary for fresh raw meat, fish, or poultry and fresh fruits and vegetables, but many markets — perhaps under pressure from customers — have put posters or brochures with generic nutrition information near the meat counter or produce bins.

Getting the facts

The star of the Nutrition Facts Label is the Nutrition Facts Panel on the back (or side) of the package. This panel features three important elements: serving sizes, amounts of nutrients per serving, and Percent Daily Value (see Figure 17-2).

In recent years, with the rising concern about obesity often believed to be triggered by the overconsumption of sugary foods, a new Nutrition Facts Label has been evolving. This one wouldn’t simply list “sugars.” It would break the sugar component into two categories: The sugar that occurs naturally in foods (for example, the natural sugars in an apple) and the sugars added to a food (for example, the sugars added to packaged apple sauce). In addition, instead of showing simply the percentage of the RDA (Recommended Dietary Allowance) for vitamins and minerals and requiring you to guess what the total figure is, the new labels show the exact amount (for example, 260 milligrams calcium) plus the percentage of the RDA (20 percent). Note that these values are required only for certain vitamins and minerals — others are voluntary.

Figure 17-3 shows the two labels, original and proposed new, side by side.

Serving size

No need to stretch your brain trying to translate gram-servings or ounce-servings into real servings. This label does it for you, listing the servings in comprehensible kitchen terms, such as 1 cup or 1 waffle or 2 pieces or 1 teaspoon. It also tells you how many servings are in the package.

The serving size is exactly the same for all products in a category. In other words, the Nutrition Facts Panel enables you to compare at a glance the nutrient content for two different brands of yogurt, cheddar cheese, string beans, soft drinks, and so on.

When checking the labels, you may think the suggested serving sizes seem small (especially with so-called low-fat items). Think of these serving sizes as useful guides, which have become more realistic over time as the FDA brought them into line with what people really eat, which is to say, not one or two fries per serving, more like ten — with the resulting calories and such.

Amount per serving

The Nutrition Facts Panel tells you the amount (per serving) for several important factors:

- Calories in a new VERY BIG TYPE

- Total fat (in grams)

- Saturated fat (in grams)

- Trans fats (in grams)

- Cholesterol (in milligrams)

- Total carbohydrate (in grams)

- Dietary fiber (in grams)

- Sugars, total amount and the amount of sugar added during preparation (in grams)

- Protein (in grams)

Percent Daily Value

The Percent Daily Value enables you to judge whether a specific food is high, medium, or low in fat, cholesterol, sodium, carbohydrates, dietary fiber, sugar, protein, vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and iron based on a set of recommendations called the Reference Daily Intakes (RDI), which are similar (but not identical) to the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for vitamins and minerals discussed in Chapters 10 and 11.

RDIs are based on allowances set in 1973, so some RDIs now may not apply to all groups of people. For example, the Daily Value for calcium is 1,000 milligrams, but many studies — and two National Institutes of Health Conferences — suggest that postmenopausal women who are not using hormone replacement therapy need to consume 1,500 milligrams of calcium a day to reduce their risk of osteoporosis.

The Percent Daily Values for fats, carbohydrates, protein, sodium, and potassium are based on the Daily Reference Values (DRV). DRVs are standards for nutrients, such as fat and fiber, known to raise or lower the risk of certain health conditions, such as heart disease and cancer.

Relying on labels: Health claims

Ever since man (and woman) came out of the caves, people have been making health claims for certain foods. These folk remedies may be comforting, but the evidence to support them is mostly anecdotal: “I had a cold. My mom gave me chicken soup, and here I am, all bright-eyed and bushy-tailed. Of course, it did take a week to get rid of the cold.”

On the other hand, health claims approved by the USDA and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for inclusion on the new food labels are another matter entirely. If you see a statement suggesting that a particular food or nutrient plays a role in reducing your risk of a specific medical condition, you can be absolutely 100 percent sure that a real relationship exists between the food and the medical condition. You can also be sure that scientific evidence from well-designed studies supports the claim.

In other words, USDA/FDA-approved health claims are medically sound and scientifically specific. They highlight the known relationships between

- Calcium and bone density: A label describing a food as “high in calcium” may truthfully say: “A diet high in calcium helps women maintain healthy bones and may reduce the risk of osteoporosis later in life.”

- A diet high in fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol and a higher risk of heart disease: A label describing a food as “low fat, low cholesterol,” or “no fat, no cholesterol” may truthfully say: “This food follows the recommendations of the American Heart Association’s diet to lower the risk of heart disease.”

- A high-fiber diet and a lower risk of some kinds of cancer: A label describing a food as “high-fiber” may truthfully say: “Foods high in dietary fiber may reduce the risk of certain types of cancer.”

- A high-fiber diet and a lower risk of heart attack: A label describing a food as “high-fiber” may truthfully say: “Foods high in dietary fiber may help reduce the risk of coronary heart disease.”

- Sodium and hypertension (high blood pressure): A label describing a food as “low-sodium” may truthfully say: “A diet low in sodium may reduce the risk of high blood pressure.”

- A fruit-and-vegetable-rich diet and a low risk of some kinds of cancer: Labels on fruits and vegetables may truthfully say: “A diet high in fruits and vegetables may lower your risk of some kinds of cancer.”

- Folic acid (folate) and a lower risk of neural tube (spinal cord) birth defects such as spina bifida: Labels on folate-rich foods may truthfully say: “A diet rich in folates during pregnancy lowers the risk of neural tube defects in the fetus.”

Navigating the highs and lows

Today, savvy consumers reach almost automatically for packages labeled “low-fat” or “high-fiber.” But it’s a dollars-to-doughnuts sure bet that hardly one shopper in a thousand knows what “low” and “high” actually mean.

Because these are potent terms that promise real health benefits, the new labeling law has created strict, science-based definitions:

Because these are potent terms that promise real health benefits, the new labeling law has created strict, science-based definitions:

- High means that one serving provides 20 percent or more of the Daily Value for a particular nutrient. Other ways to say “high” are “rich in” or “excellent source,” as in “milk is an excellent source of calcium.”

- Good source means one serving gives you 10 to 19 percent of the Daily Value for a particular nutrient.

- Light (sometimes written lite) is used in connection with calories, fat, or sodium. It means the product has one-third fewer calories or 50 percent less fat or 50 percent less sodium than usually is found in a particular type of product.

- Low means that the food contains an amount of a nutrient that enables you to eat several servings without going over the Daily Value for that nutrient.

- Low calorie means 40 calories or fewer per serving.

- Low fat means 3 grams of fat or less.

- Low saturated fat means less than 0.5 grams trans fat per serving and 1 gram (or less) saturated fat.

- Low cholesterol means 20 milligrams or less.

- Low sodium means 140 milligrams sodium or less per serving; a diet plan with less than 1,000 milligrams of sodium per day is considered a low-sodium diet.

- Reduced saturated fat means that the amount of saturated fat plus trans fat has been reduced more than 25 percent from what’s normal in the given food product.

- Free means “negligible” — not “none.” In short, this is what counts as “free” preserving:

- Calorie-free means fewer than 5 calories.

- Fat-free means less than 0.5 grams of fat.

- Trans fat-free means the food has less than 0.5 grams trans fat and 0.5 grams saturated fat per serving.

- Cholesterol-free means less than 2 milligrams of cholesterol or 2 grams or less saturated fat.

- Sodium-free or salt-free means less than 5 milligrams of sodium.

- Sugar-free means less than 0.5 grams of sugar.

And if that isn’t enough to occupy your food brain, consider this: The FDA is currently seeking comments on how to define the word natural on food labels. The agency explains that “[f]rom a food science perspective, it is difficult to define a food product that is ‘natural' because the food has probably been processed and is no longer the product of the earth. That said, FDA has not developed a definition for use of the term natural or its derivatives. However, the agency has not objected to the use of the term if the food does not contain added color, artificial flavors, or synthetic substances.” Pass the “natural, organic” aspirin, please!

Listing other stuff

The extra added attraction on the Nutrition Facts Label is the complete ingredient listing, in which every single ingredient is listed in order of its weight in the product, heaviest first, lightest last. In addition, the label must spell out the true identity of some classes of ingredients known to cause allergic reactions:

- Vegetable proteins (hydrolyzed corn protein rather than the old-fashioned hydrolyzed vegetable protein)

- Milk products (nondairy products, such as coffee whiteners, may contain the milk protein caseinate, which comes from milk)

- FD&C yellow No. 5, a full, formal chemical name instead of coloring

Naming the precise source of sweeteners (corn sugar monohydrate rather than just sugar monohydrate) is still voluntary, but as is true of information about raw meat, fish, and poultry, manufacturers and stores just may respond to consumer pressure.

Using the Pyramid, Plate, and Label to Choose Healthful Foods

The Food Guide Pyramids and Plate are designed to help you balance meals and snacks. For example, although you know that fruits and veggies are good snacks, that doesn’t mean you’re stuck with boring carrot sticks or an apple. The pyramid says “fruits and vegetables,” not “totally raw fruits and raw vegetables.” Yes, a fresh apple’s fine. But so is a baked apple (100 calories), fragrant with cinnamon and decorated with no-fat sour cream (30 to 45 calories for 2 tablespoons). Carrot sticks are okay. So are vegetarian baked beans — yes, baked beans, which are considered both veggies and a member of the high-protein meat/beans group at 140 calories plus 26 grams of carbohydrates, 7 grams of protein, 7 grams of dietary fiber, and 2 grams of fat per ½ cup serving. As for the Nutrition Facts Label, you can use that to eat your cake and have it nutritiously by comparing products to choose the best alternatives.

Here’s a good example: You find yourself irresistibly drawn to double dark chocolate ice cream (lots of fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and a whopping 230 calories per ½ cup serving). But then, just as your hand is opening the freezer door, ready to reach for the ice cream, suddenly … out of the corner of your eye, you see the Nutrition Facts Panel on the label of the no-fat but equally irresistible chocolate sorbet. It says, “No fat, no saturated fat, no cholesterol, and only 90 to 130 calories per serving.” When you put the labels side by side, do you need to ask which one comes out the winner?

Because you get to indulge while protecting your nutrition status, you opt for the irresistible chocolate sorbet. Who could ask for anything more?

Because these are potent terms that promise real health benefits, the new labeling law has created strict, science-based definitions:

Because these are potent terms that promise real health benefits, the new labeling law has created strict, science-based definitions: