Diagnosing Food Allergies

Your immune system is designed to protect your body from harmful invaders, such as bacteria. Sometimes, however, the system responds to substances normally considered harmless. The substance that provokes the attack is called an allergen; the substances that attack the allergen are called antibodies.

A food allergy can provoke such a response as your body releases antibodies to attack specific proteins in food. When this happens, some of the physical reactions include

- Hives

- Itching

- Swelling of the face, tongue, lips, eyelids, hands, and feet

- Rashes

- Headaches, migraines

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Diarrhea, sometimes bloody

- Sneezing, coughing

- Asthma

- Breathing difficulties caused by tightening (swelling) of tissues in the throat

- Loss of consciousness (from anaphylactic shock)

Understanding how an allergic reaction occurs

When you eat a food containing a protein to which you’re sensitive, the protein reaches antibodies on the surface of white blood cells called basophils and immune system cells called mast cells either in your gastrointestinal tract or by circulating through the bloodstream.

The basophils and mast cells produce, store, and release histamine, a natural body chemical that causes the symptoms — itching, swelling, hives — associated with allergic reactions (some allergy pills designed to counter this are called antihistamines). When the antibodies on the surface of the basophils and mast cells come in contact with food allergens, the cells release histamine, and the result is an allergic reaction.

Investigating two kinds of allergic reactions

Your body may react to an allergen in one of two ways — immediately or later on:

- Immediate reactions are more dangerous because they involve a fast swelling of tissue, sometimes within seconds after contact with the offending food.

- Delayed reactions, which may occur as long as 24 to 48 hours after you’ve been exposed to the offending food, are usually much milder, perhaps a slight cough or nasal congestion caused by swollen tissues.

Most allergic reactions to food are unpleasant but essentially mild. However, as many as 150 or more people die every year in the United States from a severe reaction to a food allergen.

Identifying food allergies

A tendency toward allergies (although not necessarily the specific allergy itself) is inherited. If one of your parents has an allergy, your risk of having one is two times higher than it would be if neither of your parents had a history of allergic disease. If both your mother and your father have allergies, your risk is four times higher.

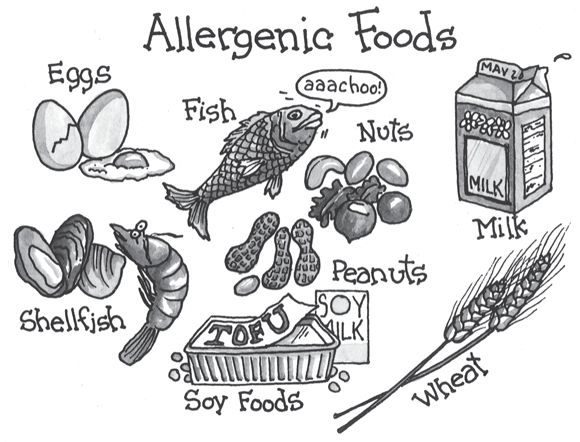

To identify the culprit causing your food allergy, your doctor may suggest an elimination diet. This regimen removes from your diet foods — most commonly milk, egg, soy, wheat, peanuts — known to cause allergic reactions in many people. Then, one at a time, the foods are added back. If you react to one, bingo! That’s a clue to what triggers your immune response.

To be absolutely certain, your doctor may challenge your immune system by introducing foods in a form (maybe a capsule) that neither you nor he can identify as a specific food. Doing so rules out any possibility that your reaction has been triggered by emotional stimuli — that is, seeing, tasting, or smelling the food.

Other tests that can identify allergens to specific foods include skin tests and two types of blood tests — ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) and RAST (radioallergosorbent test) — that can identify antibodies to specific allergens in your blood. But these two tests are rarely required.

If you’re sensitive to a specific food, you may not have to eat the food to have the reaction. For example, people sensitive to peanuts may break out in hives just from touching a peanut or peanut butter and may suffer a potentially fatal reaction after tasting chocolate that has touched factory machinery that previously touched peanuts. People sensitive to seafood — fin fish and shellfish — have been known to develop breathing problems after simply inhaling the vapors or steam produced by cooking the fish.

If you’re sensitive to a specific food, you may not have to eat the food to have the reaction. For example, people sensitive to peanuts may break out in hives just from touching a peanut or peanut butter and may suffer a potentially fatal reaction after tasting chocolate that has touched factory machinery that previously touched peanuts. People sensitive to seafood — fin fish and shellfish — have been known to develop breathing problems after simply inhaling the vapors or steam produced by cooking the fish. If you’re sensitive to one of these foods, the best way to avoid an allergic reaction is to avoid the food. And you can do that by reading the label to ferret out hidden ingredients — peanuts in the chili or caviar (fish eggs) in the dip.

If you’re sensitive to one of these foods, the best way to avoid an allergic reaction is to avoid the food. And you can do that by reading the label to ferret out hidden ingredients — peanuts in the chili or caviar (fish eggs) in the dip.