At the last moment, Gerda Kronstein’s mother confessed she would not be going with her daughter to America after all. They never saw each other again.

Anna Pauline Murray was three years old when her mother died. Neighbors whispered that it was probably suicide, that she must have been driven to it by her husband, Will, whose deep depressions and violent “fits” had taken him to a hospital more than once. In fact, she died after a cerebral hemorrhage, but the facts of her life suggested a major contributing factor: She was in the fourth month of her seventh pregnancy in 11 years; she was married to a clearly sick man; and she was overworked as a nurse and mother of six. After she died, Will came apart, and relatives committed him to an asylum near their home in Baltimore for what turned out to be the rest of his life. The children went to relatives. Anna Pauline was sent alone to Durham, North Carolina, to live with her mother’s parents and the relative she knew best, her mother’s sister and her namesake, Pauline Dame, who legally adopted her and whom she came to call Mother.

The next time Anna Pauline saw her father she was almost nine. She could not wait to see him. Her relatives by then had told her why her mother had fallen in love with him, though little of the rest. Her picture of him was of a dashing, intelligent, Howard University graduate: a natural athlete, teacher by profession, pianist, poet, and omnivorous reader—a man with a seemingly endless appetite for intellectual growth. Anna Pauline admired that drive and wished to let her father know she had it too. “I could not wait to see him,” she wrote later. “I knew exactly how he would look, and I knew he would remember me because people said I looked so much like him and had his quick mind. I was bursting to tell him all about school and that I was on the Honor Roll in my class.” The haggard, unshaven man brought out to see her, however, was nothing like the father she thought she knew, and he clearly did not know who she was. That was her last living memory of him. The next time she saw him was a few years later, at his funeral, after he was beaten to death by a white orderly who found him “uppity.”

Anna Pauline Murray spent a great deal of her life as she spent her childhood, among disorienting losses and fissures in what she called a “confused world of uncertain boundaries.” Until her mother’s death and then at her grandparents’ home, she was raised in relative comfort, a child of the Black middle class. Her family were nurses, teachers, landowning professionals, and members of the Episcopal church. They had some of the advantages that came with light skin, but their distinctions of complexion, class, and ancestry also made for confusion. Her grandparents, Robert and Cornelia Fitzgerald, were descended from both slaves and slave owners, from Quakers and rapists. Robert had fought for the Union in the Civil War, while Cornelia was actually proud of her Confederate heritage—this despite the fact that her mother was a slave raped repeatedly by her owner’s two sons, one of whom was her biological father. For Anna Pauline, to live with these grandparents was to witness “a tug of war between free-born Yankee and southern aristocrat,” between a man who had been willing to give his life to end slavery and a child of rape who was proud that her father could afford 30 slaves. Murray herself was what she described later as a “borderline racial type,” darker than her grandparents but light-skinned enough to be resented and taunted by her Black schoolmates. “In a world of black-white opposites,” she wrote later, “I had no place.”

She lived with a more agonizing ambiguity as well. In her teens, she became convinced that something was physically wrong with her—that she was born to be a man. Over the years, she wrote to one physician after another seeking a medical reason for her confused gender. She could not identify as a lesbian because she was attracted most often to heterosexual women, which meant suffering a series of painful rejections. Among the ways she dealt with her conflicted gender was to try and embrace it. She changed her name to the gender-indefinite “Pauli,” and among her papers she left pictures of herself in her twenties in various poses and outfits, captioned “the Imp,” “Pixie!,” “the Dude,” “the Crusader,” and “Pete,” perhaps trying on identities, perhaps for self-assertion, perhaps both.

Her lack of certainty about race and gender defined the most intimate challenges Pauli Murray faced during her life. They also prompted the advances she made for civil rights and women’s rights during her long legal career, including the argument that ultimately persuaded the Supreme Court to outlaw discrimination on the basis of sex. Like other feminist pioneers at the time, her life was a hero’s journey decades long but little noted until the late twentieth century, when scholars began to retrieve a history that was missing in the Second Wave urtext, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique.

As the name implied, Second Wave feminism was taken to be the first upsurge of activism for women’s rights since 1920, when the suffrage movement and ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote. Forty years later, Friedan detected a resurgent impulse for liberation among women, which she described as “buried, unspoken,” confined to “a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction” that was nowhere evident “in the millions of words written about women, for women….”

In fact, the oppression of the “happy housewife” was a central message in numerous articles by the Columbia University sociologist Mirra Komarovsky and in her Women in the Modern World of 1953, which was also the year Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex was published in English. Almost a decade before those books, the connection between gender and racial discrimination was discussed in an appendix to Gunnar Myrdal’s historic study of racism, An American Dilemma, and in 1956 the plight of the educated woman was confronted directly by his spouse, Alva Myrdal, in her collaboration with Viola Klein, Women’s Two Roles: Home and Work. Three years later, Eleanor Flexner published her groundbreaking Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States. Given all that had been written already about “the woman problem,” the publisher of The Feminine Mystique actually worried that Friedan’s book would have to “fight its way out of a thicket.” Unlike those writers, however, Friedan was a practiced and articulate polemicist who was also used to writing for a mass audience, and she was not above a little cosmetic overstatement. “To women born after 1920,” Friedan wrote, “feminism was dead history.”

She knew better than that. As her biographer Daniel Horowitz disclosed in his 1998 biography, she had been advocating for the rights of women for almost 20 years before The Feminine Mystique was published. From her first job after graduation from Smith College in 1942, she was a journalist for left-wing unions that promoted Rosie the Riveter during the war, and she protested Rosie’s demotion to homemaker and domestic worker when the veterans came home and took her jobs. One of Friedan’s first articles in that first job was a salute to Elizabeth Hawes, a fashion designer turned UAW organizer and author of the new book Why Women Cry: Or, Wenches with Wrenches. “Men, there’s a revolution cooking in your own kitchens,” Friedan wrote in 1943, “a revolution of the forgotten female, who is finally waking up to the fact that she can produce other things besides babies.” Her position in The Feminine Mystique had been clear 20 years earlier in the way she spoke for Hawes:

No woman on God’s earth… wants to have her entire life swing around a solitary, boring, repetitive business which means exhausting herself washing the same dishes and clothes day in and day out—cooking food for the same people, seldom seeing a living soul other than a tired husband and her own children for more than a very short time.

At the Federated Press and later at the news service of the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America, Friedan’s writing on women’s issues was as radical as her employers would allow it to be.

In 1952, pregnant with her second child, Friedan was laid off, as was the only other woman on the writing staff. After that, she softened her rhetoric in articles for mass-market women’s magazines but even then advocated for the right of women to pursue fulfillment in the world of work and to defeat whatever stood in their way, including chauvinist husbands. Yet in 1972, a decade after finishing The Feminine Mystique, she wrote in the New York Times: “Until I started writing it [in 1957], I wasn’t even conscious of the woman problem.”

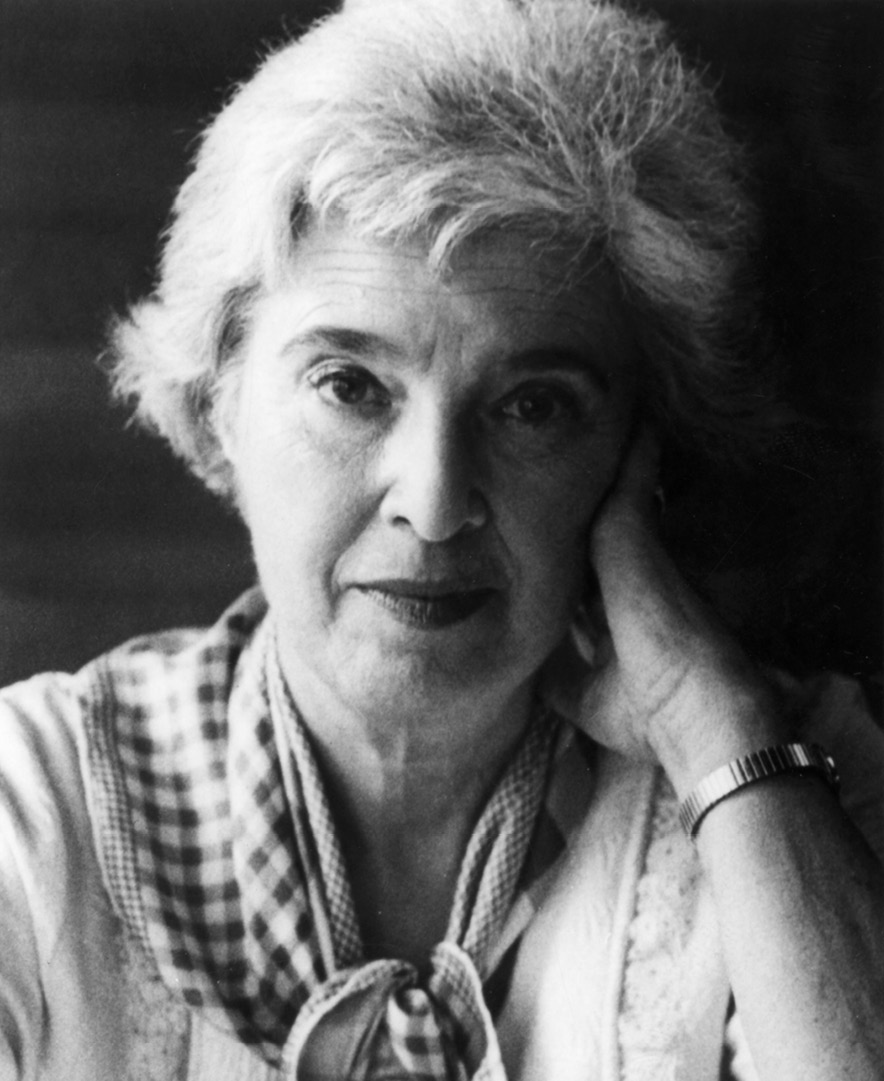

Years before Daniel Horowitz disclosed the early career of Betty Friedan, scholars were already beginning to rewrite the history of feminism, particularly the role played by distinctions of race and class. Any short list would omit many important works, but a historic beginning was made by Gerda Lerner, née Kronstein, the privileged daughter in an Austrian Jewish family who barely escaped Nazi-occupied Vienna. In 1939, at the age of 19, she managed to reach exile in the U.S., where her experience of anti-Semitism and identification with other oppressed people would lead her to the study of racial, ethnic, gender, and other discriminations. By the time The Feminine Mystique was published, she was teaching the first college course in the U.S. devoted to women’s history. She read Friedan’s book just days after it was published and decided immediately to include it in her course. She wrote Friedan to compliment her on her “splendid” book but also to point out what she considered its greatest flaw. “[I]t addresses itself solely to the problems of middle-class, college-educated women,” she wrote.

This was one of the pitfalls of the suffrage movement for many years and has, I believe, retarded the general advance of women. Working women, especially Negro women, labor under… disadvantages imposed upon them by both economic oppression and the feminine mystique…. To leave them out of consideration of the problem or to ignore the contributions they can make toward its solution, is something we simply cannot afford to do.

She could have been thinking of Fannie Lou Hamer, a 45-year-old sharecropper, wife, mother, and activist in the Mississippi Delta, who, in the same year Friedan’s book was published, was shot at, jailed, beaten mercilessly, and thrown off her plantation for trying to vote—a woman who, through it all, held to what her mother and her church had taught her: You had to keep loving even the worst white people because they were sick, and they needed a doctor. Thirty years later, the prominent civil rights activist Unita Blackwell remembered the first time she heard Hamer saying that, because she thought it amounted to letting racists off the hook: “I was so angry that day, listening to all her stuff…. I said, ‘This woman is crazy.’ ”

Pauli Murray and Gerda Lerner were crazy that way too: intuitive and brave enough to look directly at their most complex and painful challenges, to find their source, and then to act on what they saw, whatever the cost. Among other things, they saw that race, class, and gender were inseparable, mutually reinforcing sources of discrimination that could only be defeated on the basis of that understanding. Against the punishing, reactionary tide of 1950s America, they and others fought for that elusive goal with sufficient imagination, force, and foresight that, more than two decades later, a professor at the UCLA School of Law—Kimberlé Crenshaw—could articulate its legal force and give it a name: intersectionality.

Gerda Kronstein was 13 years old when civil war broke out around her family home in Vienna. The occupation of Austria by Nazi Germany was still four years in the future, but when Hitler declared his intention to unite all German-speaking peoples, Austria’s chancellor turned away from democracy, canceled freedom of the press, ended jury trials, ignored the legislature, and put protesters in jail. With that, a scattered movement for Austrian freedom and independence rose up in armed resistance.

At the last moment, Gerda Kronstein’s mother confessed she would not be going with her daughter to America after all. They never saw each other again.

Gerda would remember February 12, 1934, as the day gunfire broke out near her home. Minutes later, her father called from his pharmacy to tell them to light candles and fill the bathtubs with water. The trade unions had called for a general strike, he said, and the fighting was going to get worse. Just after he hung up, the telephone went dead, and then all the lights went out. The shooting went on all night and was joined the next morning by the sound of cannon fire. The radio played only Strauss waltzes and martial music all day long, occasionally interrupted by an announcement that the rebellion had been crushed, even as continuing gunfire declared the opposite. The artillery was aimed at the Karl-Marx Hof, a nearby housing project for workers. “There are women and children in there,” she heard her mother whisper to her father. “How could they do that?”

Like Pauli Murray, Gerda Kronstein lived in ambiguous, painful, potentially dangerous territory. She was raised in luxury, but she was Jewish in an expressly Roman Catholic and increasingly anti-Semitic country. Her parents lived together and apart, their marriage literally reduced to a signed, legal agreement. They had separate apartments in the family home, and each had another home as well. Her father lived with another woman, and her mother had a painting studio where she entertained. Her mother showed little interest in women’s traditional roles. She left the cooking and housework to maids and the children’s care to governesses. Her passion was her art—her friends and houseguests were artists—and she dressed the part, leaving aside the fashion of the Viennese haute bourgeois for hoop earrings, loose-fitting blouses, colorful floor-length skirts, and sandals. Gerda was closest to her father’s mother, who also had an apartment in the family home and who made no secret of the fact that she despised Gerda’s mother.

In self-defense, Gerda prepared herself for life in a theater of family conflict by becoming combative herself, even as she internalized the self-image of “a misfit, a freak, an outcast.” In secondary school, she began taking the long way on her walk to school, a detour through lives like those being lived in the Karl-Marx Hof. Though the families were poor, they seemed to her more vividly alive than her own. She envied even the children from the local orphanage, whom she saw laughing as they walked to school together: At least they had each other.

As Austria’s Nazi movement rose in influence, Gerda helped her parents get rid of every politically sensitive book and magazine in the family library, but away from home, she studied sedition. At a time when being caught reading literature from the Communist Party underground was a criminal offense, she cherished whatever she could find or borrow from friends, which kindled her passion for politics and her ambition to become a writer herself. At night, when no one could hear, she listened to Radio Moscow on the family’s shortwave radio to find out what was happening in Germany, how much worse it was there: the Nazis’ all-out war on Communists, the humiliations, roundups, and abuse of Jews. Her early sympathy with Communism, she wrote later, “allowed me to find a territory of my own.” In retrospect, it seemed to her “a desperate choice,” but “defining myself as an outsider and moving toward danger the way the swimmer moves toward the breaking wave—these two tendencies shaped my character and being.”

In March 1938, one week after Hitler’s forces arrived to occupy Austria, Gerda’s father left the country. He promised he would make a new life for them in Liechtenstein, and then, taking as much as he could carry, he made his way across the border. Not long after that, storm troopers came looking for him. To pressure him to turn himself in, they took Gerda and her mother to prison as hostages. Six weeks later, after the family pharmacy and other assets had been turned over, they were told they were free to go as long as they agreed to leave Austria and never return. Gerda’s mother quickly sold their home and possessions for pennies, and they left Austria, lucky to be alive.

By 1939, Gerda’s mother was in the South of France, having found a life like the one she left, as a painter in a community of fellow artists. Gerda managed to get a visa to the U.S. thanks to a boyfriend who had made his way there earlier and who sponsored her as his fiancée. She joined him in Harlem, where he had a steady job, but their marriage of convenience soon lapsed into an amicable divorce. At that, she sank into desperate poverty. Unable to get work in the last days of the Depression, she came close to starving. At the same time, as France fell to the Nazis, her mother’s letters became increasingly desperate, pleading for help that Gerda was powerless to provide. Her mother managed to survive life in a Nazi detention camp but died a few years after the war, and Gerda never saw her again except in guilty dreams.

Her only financial support was one low-paid temporary job after another. Friendless and shunned by the anti-Semitic German community, she found herself most at home with the African American women who were her neighbors. They too were shunned and denied the standing of citizens. They too were poor and displaced people in flight from discrimination and its cruel enforcements. They were suspicious of her at first, but she felt the distance between them close as she told the story of her own imprisonment, forced emigration, and ostracism in America.

She managed to find a place for herself in the left-wing theater community, which is where she met Carl Lerner, her husband until the day he died 33 years later. They were brought together by a script she had written for New York’s annual German American Day for Peace and Progress, which drew left-wing activists, including members of the U.S. Communist Party. Carl Lerner was then an out-of-work but experienced theater director, and he revised Gerda’s script in ways she had to admit were major improvements. Working together led to a mutual affection that led to marriage, two children, and a life of activism together, in and out of the Communist Party.

Carl had been a member of the Party for years when they married. Gerda was not, but the difference was almost a technicality. They volunteered, went to meetings and fund-raisers together, and believed, together with thousands of other Americans, that Marxism held the promise of greater equality and justice and the hope of a better world. It seemed to them that Communism was as American as the Declaration of Independence, and that Americans had simply lost touch with their revolutionary roots.

In a few years, it would be hard to imagine there was ever such a time, but during the Depression and the wartime alliance, the story of Soviet Communism was easy to love. By dethroning absolutism, so the story went, the Bolsheviks were ending the long oppression of Russia’s workers and peasants. Poverty, famine, and illiteracy were under sustained assault. The industrial base and economy of the Soviet Union were growing stronger every day, and the elite hoarders of wealth—like the rapacious U.S. financiers accused in the 1930s of fabricating the fool’s-gold 1920s—were said in Russia to be gone with the czars. Americans who went to Russia to see for themselves brought home to a nation of bread lines and despair the story of a bold, young country undertaking a great experiment: a new kind of democracy, a government that was truly of, by, and for the people, and an alternative to capitalism that promised increases in both equality and liberty, including freedom from want.

It was evident even then that there were problems with that story, but as the Soviet Union bore by far the greatest cost in human lives during World War II, even such staunch anti-Communists as the publisher Henry Luce allowed his magazines to speak well of it. In 1943, in a special issue on Russia, Luce’s Life magazine actually described Lenin as “perhaps the greatest man of modern times… a normal, well-balanced man who was dedicated to rescuing 140,000,000 people from a brutal and incompetent tyranny. He did what he set out to do.”

Gerda finally joined the Party in a spirit of defiance, at a time when friends who had supported the Soviet-backed Loyalists during the Spanish Civil War were being investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee as “premature anti-fascists,” presumed to be Communist dupes, comrades in hiding, or both. Carl’s film career was nearly destroyed by the film industry’s blacklist, but even then he and Gerda both persisted in Party work because they still believed in its ideals and refused to be intimidated by fear.

Gerda’s best memory of her Party work was helping to start the Congress of American Women (CAW), a branch of the Soviet-backed Women’s International Democratic Federation and the first feminist organization the U.S. Communist Party had ever supported. Before the war, the American Party had taken less than no interest in women’s rights, considering it a bourgeois distraction from the class struggle. The Daily Worker made its position clear on the “women’s page,” which was full of cooking and housecleaning tips and pictures of barely clothed models under headlines such as “Mrs. New York—And She Can Cook Too!” In the late 1930s, when a book-length reexamination of “the Woman Question” made the rounds of Party publications on the East Coast, every one of them refused to excerpt it. But as the war came to a close and women began losing jobs to returning veterans, the Party’s long-standing commitment to fight racism (“white chauvinism”) was linked to the cause of ending male supremacy, for which the Party coined the term “male chauvinism.”

At that, the Daily Worker transformed the woman’s page from household hints and recipes into a forum for ideas. Like the Party, the Congress of American Women strongly supported legislation against lynching and racial discrimination, but its feminist agenda otherwise ran ahead of the Party’s. Along with issues such as equal pay, government-sponsored day care, and job protections, CAW’s feminism was joined to its commitment to interracial leadership and membership. Theirs was a feminism not separate from but inclusive of civil rights, and no one did more than Lerner to model the kind of self-examination and candor necessary to overcome racial barriers to trust, as she had learned to do during her first days in the U.S. She wrote decades later that her time in CAW was the best political experience she had ever had.

Like others, she was heartbroken when, in 1950, CAW surrendered to the fate of other left-wing organizations. A report by the House Un-American Activities Committee denounced it as “a specialized arm of Soviet political warfare” whose true mission was to render the U.S. and its allies “helpless in the face of the Communist drive for world conquest.” After long debate, the board of CAW voted to disband rather than fight a prolonged, expensive, and almost certainly losing battle to avoid registering under the Foreign Agents Registration Act, which would subject its members to surveillance and charges of subversion.

Even after that, the Lerners continued for some time to brave the witch hunt and join every progressive cause and picket line—against the war in Korea, against nuclear weapons, and against the many outrages of McCarthyism. In their interracial community in New York City’s borough of Queens, Gerda’s activism included mobilizing her PTA to demand needed improvements to her children’s school building and to replace the principal who had presided over its decline. At the same time, she worked at home on a second novel, the first having failed to find a publisher. In other words, without setting out to do so, Lerner proved that a woman could have a close family, a consuming career, and a life of activism—that she could “have it all.” Besides her own fierce drive, her supports included a loving husband, a band of comrades, and the sage advice of a good friend: “If you want to be a writer, you have to be a sloppy housekeeper.”

By the middle of the 1950s, however, she was near despair. Her second novel, like her first, could not find a publisher, and she thought her years of work as a writer had come to nothing. At the same time, Nikita Khrushchev’s revelation of Stalin’s many crimes convinced both her and Carl, with deep regret, to leave the Party and their ever fewer comrades. As she had helped her parents purge their library in Vienna, she threw every evidence of her connection to the Congress of American Women into the fireplace, and after that she did not talk about her membership or work in the Party for decades.

At this point in her autobiography, Lerner paused to remember what it was like to climb the mountains of Austria when she was young, how much more difficult it was as the climb steepened near the top. That was when weather closed in, the trail disappeared in rock, and you knew that, as near the summit as you seemed to be, the most arduous climb lay ahead. “It is then that you take one small laborious step after the other,” she wrote. “Forget the goal, forget the possibility of failure…. This is the time when the mind forces the body to do more than it can.”

She began another book, this one a historical novel based on the lives of the sisters Sarah and Angelina Grimké, white women of the South who were pioneers for racial and gender equality in the nineteenth century, several years before the suffrage movement began. The subject spoke directly to racial conflict in the suffrage movement, but when she had written eight chapters of their story as a novel, she realized it needed detail she could only collect with the tools of a professional historian. So, in 1958, at the age of 38, she enrolled as an undergraduate history major at the New School for Social Research, where she began the climb to the summit of her career.

By 1962, she was teaching women’s history at the New School, which is said to be the first such college-level course taught in the U.S. Thanks to her personal history and her years in the Congress of American Women, she brought to her students a race- and class-inflected history of feminism that reached back to slavery and pointed beyond The Feminine Mystique. In just three years, she worked her way through both a master’s degree and a PhD in history at Columbia University, where she fashioned her own curriculum to concentrate on the history of women. She abandoned her novel to make the Grimké sisters the subject of her dissertation, which also became her first published book, the first of 12 books she wrote in the field she helped develop and championed for the rest of her life.

In her first full-time teaching job, as a professor at Sarah Lawrence, she and a colleague proposed to start the first postgraduate program in women’s history. “What I wanted to do,” she said later, “was to tell this generation that is now teaching and the students that, first of all, nobody gave us anything. It makes me furious when I hear that they gave us suffrage. Excuse me, it took 72 years of organizing, grassroots effort…. [W]e had to fight every inch of the way for every advance, and against constant resistance.” Lerner had to fight for the field of women’s history too. The faculty of Sarah Lawrence’s history department argued that there was no reason to divide history by gender, and in any case, they said, there were not enough primary sources for such a program. Columbia professor Alice Kessler-Harris, who was also early to women’s history studies, recalled that, at the time, that “seemed a perfectly good explanation.” As she also remembered, “Gerda would have none of it.”

Thanks in no small part to Gerda Lerner’s scholarship and persistence, the distinctive place of women in history would come to be well known, and there would be departments of women’s history and women’s studies in most major U.S. colleges and universities. Some of its leading scholars were her former students.

The picture taken of 20-year-old Pauli Murray as “Pete” actually appeared in Negro Anthology: 1931–1933, a collection of writings from the Harlem Renaissance. Her story, titled “Three Thousand Miles on a Dime in Ten Days,” was the first she ever published. The byline was “Pauli Murray,” but the photo, captioned “Pete,” appears to show a young man sitting on a concrete block in workers’ clothes and a sailor’s cap, smiling broadly and leaning into the picture, hands clasped around one knee. Decades later, the story could clearly be read as a portrait of Murray’s divided self. “Pete” was the hero of the story, but the narrator’s voice was that of an easily frightened traveling companion, a genderless observer but one who clearly admired Pete’s fearless confidence.

The story was inspired by a train-hopping cross-country trip that Murray had made with her friend Dorothy Hayden. That trip began and ended in New York City, where Murray had lived since graduating high school. In 1933, at the age of 23, she got her BA at the then tuition-free Hunter College for Women, but she also got an education where she lived, at Harlem’s new YWCA, on 137th Street. The building took up an entire city block and was a center of the Harlem Renaissance. There, she found mentors for her writing in Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen, and she became friends with women who would be leaders in the civil rights movements of the 1950s and ’60s, including Ella Baker, Anna Arnold Hedgeman, and Dorothy Height. Baker introduced her to left-wing Depression-era politics by sending her downtown to the radical Worker’s School and night classes with its founder, Jay Lovestone, the former leader and now enemy of the Communist Party. Lovestone taught Murray enough to know that neither the Party nor Lovestone’s oppositional variant were appealing to her, even if some of their values were.

Only odd jobs kept Murray alive in the ’30s, when her thoughts and free time were preoccupied by her conflicted sense of gender. She spent days and weeks in the New York Public Library, researching the subject. Even then, some of the latest books and papers were proposing that gender was not binary but a spectrum from male to female, an idea that was intellectually satisfying to her but emotionally useless against the repeated agony of her rejection by heterosexual women. She found one plausible explanation of her gender confusion in Havelock Ellis’s definition of the “pseudo-hermaphrodite,” which also did little to help. Her letters appealing to physicians and psychiatrists left no doubt of her desperation, but they also demonstrated a lucidity and level of detail that spoke to her fearlessness in grappling with her predicament rather than retreating into denial.

Finally, in the late 1930s, she found a job she valued for the work itself, and one that would lead directly to her future. She was hired by A. Philip Randolph’s Workers Defense League to generate financial support for the appeal of a Virginia sharecropper named Odell Waller, who had been sentenced to death for murdering his white sub-landlord over his family’s rightful share of the harvest. Waller claimed self-defense, and there was little evidence to contradict him, but the verdict and sentence were decided in the usual southern manner—in a matter of minutes, by an all-white jury. Like other southern states, Virginia created such juries by limiting its pool of jurors to registered voters and by imposing a poll tax that kept most Black and poor white citizens from registering. The NAACP took on Waller’s appeal as a way of attacking the poll tax, which had denied him a jury of his peers. For most of a year, Murray traveled the country with Waller’s mother to plead his case, in the course of which she became fluent in arguing from the Fourteenth Amendment’s promise to every citizen of “equal protection of the laws.” All along their cross-country tour, she recalled later, “I kept saying to myself, ‘If we lose this man’s life, I must study law.’ ”

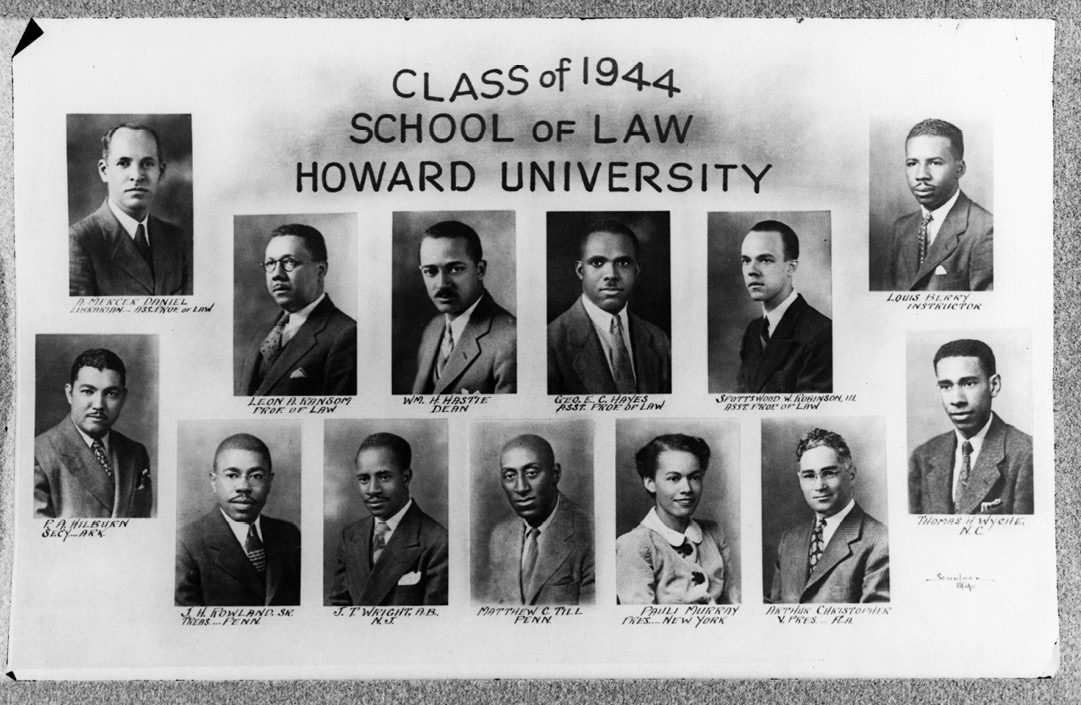

One night in Richmond, Virginia, she made her appeal to a meeting of Black ministers. Among the speakers, and among the audience for her presentation, were the celebrated civil rights attorneys Thurgood Marshall and Leon Ransom, who was then the acting dean at Howard University’s School of Law. Intimidated by their presence in the audience but also simply exhausted from her time on the road, she remembered, “I get out two words, then just utterly collapse in tears trying to tell the story of this young sharecropper.” When she recovered, she obviously made her case, because she came away with $23 from the ministers and Ransom’s offer of a full scholarship to Howard’s School of Law.

Being the only woman in her all-male class at Howard University School of Law gave Pauli Murray her fateful exposure to gender discrimination.

It was there, in the early 1940s, that Murray recognized the kind of discrimination she would later help to make illegal. Her graduating class was not only exclusively Black but was also, with the sole exception of herself, all male. Until then, she had traced every discrimination against her to racism. Now, as the lone female, and perhaps especially as one who identified as a Black man, she began for the first time to recognize the sting of sexism and gender discrimination. On the first day of classes, a professor remarked how strange it was to have a woman there. He guessed they would all just have to get used to it, he said, which brought out a burst of laughter that left her “too humiliated to respond.” After that, she noticed that fellow students sometimes seemed to be laughing at her behind her back, and it was clear in all her classes that she was called on less often than others. At first, she thought it was the softness or high pitch of her voice, but she found that trying to make it lower and louder did not help.

What finally defined the issue for her was being told, by Ransom, that she could not belong to a professional fraternity on campus because she was a woman. He denied that the decision had anything to do with Howard. A national legal fraternity was recruiting members for a new chapter on campus, he said, and it was their policy to accept only men.

At the time, Ransom and Howard’s law school were at the center of the legal struggle for civil rights. It was at Howard where some of the most important challenges to racial discrimination were devised and rehearsed. Because she respected Ransom and knew that he respected her, his response was especially, painfully meaningful. As she put it in her autobiography,

The discovery that… men I deeply admired because of their dedication to civil rights, men who themselves had suffered racial indignities, could countenance exclusion of women from their professional association, aroused an incipient feminism in me long before I knew the meaning of the term “feminism.”

That was her introduction to “Jane Crow,” the name she adopted for a set of prejudice-based customs and attitudes that asserted male supremacy and disempowered women as surely as Jim Crow laws asserted white supremacy and disempowered people of color. For the moment, gender discrimination was too personally loaded to become her mission, and those few advocates for civil rights who paid attention to it saw it as competitive with the fight against racial discrimination. At that point, Murray herself was conflicted about that and had already taken her place in the vanguard of the civil rights movement.

In 1940, the year before she began law school and 15 years before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of a city bus, Murray and her roommate Adelene McBean chose to go to jail rather than move to a broken seat at the back of a bus. It was an especially brave gesture given that Murray was traveling dressed as a man, which must have made for an interesting conversation when she insisted on sharing McBean’s cell. When they were fined and released, Murray appealed to the NAACP, which was already looking for a case to challenge segregated seating on interstate trains and buses. The NAACP chose its plaintiffs very carefully, however, and her cross-dressing may have been among the reasons they declined.

During her last semester in law school, in the spring of 1944, she led one of the first civil-rights demonstrations based on Mahatma Gandhi’s model of nonviolent resistance. With her help, seventeen years before the history-making sit-in at Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, Howard students mounted a direct-action campaign to desegregate the restaurants of Washington, D.C.

Murray’s historic contributions to the fight against both racial and gender discrimination began with her law-school thesis, which took on what even the NAACP’s best legal minds believed to be invulnerable: the “separate but equal” doctrine set down in 1896 by the Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. Until Brown v. Board of Education, the NAACP would take only cases in which “separate” facilities were not “equal” to those for whites, which left the issue of segregation per se unchallenged. Murray’s thesis laid out an assault on the “separate but equal” doctrine based on the Fourteenth Amendment, which was passed during Reconstruction precisely to ensure that the southern states would give Black Americans the rights accorded to all whites. Her argument revisited Justice John Marshall Harlan’s eloquent but as yet widely dismissed dissent in Plessy. In it, Harlan defined segregation as a legacy of slavery, exactly what the Fourteenth Amendment and its Equal Protection Clause were meant to prohibit. The Constitution recognized “no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens,” Harlan wrote, and it forbade putting “the brand of servitude and degradation upon a large class of our fellow citizens, our equals before the law.” Murray’s theory also had a contemporary source in Gunnar Myrdal’s just-published study of racism, An American Dilemma, which cited recent research to show that segregation left a legacy of long-term psychological and practical damage to its victims and the society that perpetrated it.

Years later, as Thurgood Marshall was readying his argument in the racial-discrimination cases consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education, Murray’s professor Spottswood Robinson remembered her thesis and gave it to Marshall, who incorporated it in his argument to the Supreme Court. By then, Murray had also finished a project for the Methodist Church, which had asked her to review the segregation statutes of all 48 states so that they could legally integrate as many of their local offices as possible. The result was her first book, a 776-page treatise titled States’ Laws on Race and Color. It was published in 1952, more than a year before Marshall made his argument in Brown. He bought a copy of her book for everyone on the NAACP legal team and called it their “bible” for civil rights litigation.

Despite all that she had done, Murray found that getting a good job actually practicing law was nearly impossible. At the best law firms and corporate law departments, women lawyers were scarce, and Black women were invisibly few. In 1951, she found a job possibility that matched her ambition: to work under a State Department contract to help the government of Liberia develop its legal code. Just then, however, the witch hunt caught up with her. During the application process, she got a copy of Congress’s just-released “Guide to Subversive Organizations and Publications.” Hundreds of organizations were listed, on 150 pages of small type, and Murray calculated that she had belonged to at least seven of them. She also learned that some of her references—including Eleanor Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall, and A. Phillip Randolph—were considered politically suspect. So she was bitterly disappointed but not surprised when she was disqualified on the basis of “past associations.”

Rather than continuing to hunt for a job she would not want, she decided to undertake a project she had been thinking about for years: to write a historical portrait of race in America through the story of her grandparents and their slave and slave-owning ancestors. Her friends and mentors all encouraged her to write it, and she found an agent, Marie Rodell, who believed in the idea. On the basis of an outline and sample chapters, Harper & Row gave her a $1,300 advance.

To supplement that as deadlines came and went, Rodell found her work as a typist for some of her other clients. One of them was Betty Friedan, who by then was writing for mainstream women’s magazines. Murray left no record of her reactions to what she typed for Friedan, but the magazines’ main audience of suburban housewives suggests she would have been underwhelmed. Her own subject was the South in the time of slavery and, by implication, its legacies to women of color, which she could witness in person on any weekday at what were known as New York City’s street-corner “slave markets.” There, Black women lined up for inspection every morning with their working clothes in paper bags, hoping to be hired for housework by the hour or the day.

When her book was published in 1956, Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family won lavish praise everywhere but the South, where its sale was widely banned. By then, a mentor at a prestigious law firm had managed to get her a job as an associate, but she soon tired of what she thought of as assembly-line advocacy. She left for a job in the newly independent Republic of Ghana, which had just opened a law school in Accra. There, she taught a new generation of lawyers the first course on their new constitution. She also coauthored the first textbook on Ghana’s legal history and worked to bring order from the chaos of a newborn judicial system without casebooks, trained judges, or legal precedents. She left behind a curriculum, coursework materials, and the gratitude of students and faculty.

She came home not to New York City but to New Haven, Connecticut, where she had been admitted to a doctoral program at Yale Law School. Though she intended first to focus on evolving legal systems in the newly independent African states, she was diverted by the urgency of change in U.S. laws related to race and gender. In the end, her doctoral dissertation, titled “Roots of the Racial Crisis: Prologue to Policy,” ranged well beyond law to examine the roots of racism in the “social pathologies” of American society. She set out to understand how the promise of equality and “inalienable rights” in the Declaration of Independence could possibly coexist with the cold-blooded barbarism visited on African Americans in the time of slavery and after. How could slave owners in good conscience have even signed their names to such a declaration? To square that with her belief in the founding principles, she arrived at a view of American democracy not as a fixed reality but as a hope and ambition, a promise whose fulfillment was the nation’s reason for being. In final form, her dissertation ran to 1,200 pages in five volumes and comprised a legal and social history of the U.S. that was pointedly relevant more than half a century later.

In December 1961, at the end of his first year in the White House and Pauli Murray’s first semester at Yale, President John F. Kennedy signed an executive order creating the President’s Commission on the Status of Women, and he named Eleanor Roosevelt to be its chair. She and her vice-chair, Esther Peterson, recruited some of the most powerful, connected, and smartest women in the country, creating a network among them that a few years later would help to establish the National Organization for Women.

Roosevelt recruited Murray and assigned her to the committee whose job was to find the best way to establish gender equality as a matter of law. One solution was the Equal Rights Amendment, which had been bitterly divisive ever since it was first proposed by Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party in 1923. The roots of that divide went deep. Though founded by abolitionists in 1848, the early suffrage advocates had split over the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave the vote to Black men in 1870. Infuriated by the idea that Black men would have a right denied to women, some leading suffragists were outspokenly opposed. That discord in the early movement was resolved only when it became clear that new immigrants and indigenous American women would not get the vote because they were not citizens—and that Black women, like theoretically enfranchised Black men, would be kept from the polls by bureaucratic artifice and the threat of violence.

Over time, the National Women’s Party and supporters of the Equal Rights Amendment became increasingly white, Christian, middle- to upper-middle class, and infected by racism and anti-Semitism—in other words, in sympathy with the southern Democrats who held power in Congress. That alliance of feminists and segregationists gave the Women’s Party its best chance to pass the ERA since the 1920s, but it faced an equally awkward but powerful pair of enemies: a Congress in which male dominance was the one thing southern Democrats and Republicans agreed on, allied with a strong coalition of working women who thought the ERA could ensure equality only by giving away all the gender-specific protections they had won through long, hard negotiation. So it was that the strangest of bedfellows—abolitionists and white supremacists on one side, feminists and male supremacists on the other—conspired to divide and delay the struggle for women’s rights.

When the President’s Commission on the Status of Women began its work in 1962, two of the most ardent opponents of the Equal Rights Amendment were among the Commission’s most powerful members—Esther Peterson, head of the Woman’s Bureau in the Department of Labor, and Judge Dorothy Kenyon, a social activist since the Progressive Era and a board member of the ACLU since its inception in 1930. They were Murray’s allies in the attempt to find a strategy that squared the ERA with protections for women in the workplace and that did not once again put women’s rights and civil rights at odds.

During the summer of 1962, Murray researched and drafted a proposed compromise: The President’s Commission would give tacit support to the ERA while pursuing an aggressive litigation strategy that would link discrimination by race and by gender. Despite some heated debate, Murray’s plan made it out of her committee and was adopted unanimously by the full commission.

A month before the commission presented its final report to the president, however, it was clear that legal reform would not be enough. In the list of speakers at the upcoming March on Washington and in the delegation that was to meet with President Kennedy, there was not one of the many women who had given themselves unsparingly to the civil rights movement: no Daisy Bates, leader of the long and treacherous fight to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas; no Diane Nash, leader of the Freedom Rides of 1961; no Ella Baker; no Rosa Parks.

Murray, among others, was furious. A week before the March, she sent her frank objection to the March’s leader and her onetime mentor, A. Phillip Randolph:

The time has come to say to you quite candidly, Mr. Randolph, that “tokenism” is as offensive when applied to women as when applied to Negroes, and that I have not devoted the greater part of my adult life to the implementation of human rights to now condone any policy which is not inclusive.

When her protests to Randolph and others elicited nothing but platitudes, she spent the day and night before the March writing an eight-page, single-spaced manifesto titled “The Role of the Negro Women in the Civil Rights Revolution.” She did not rant. She built her argument carefully, beginning with the oppression of American colonists by England that led to the American Revolution. African Americans were the present-day inheritors of their righteous demand for freedom, she argued, and Black women were the most egregiously oppressed of all. They were victims of discrimination by white society as well as by Black men, including the foremost champions of civil rights. The fact that no women would speak the next day was “not an oversight,” she wrote, nor was Randolph’s appearance the day before at the National Press Club, where, by tradition, women were forced to sit in the balcony. “Obviously,” Murray wrote, “Mr. Randolph and Company drew no parallel between the humiliating experience of being sent to the balcony and being sent to the back of the bus.” Black women were now being “frozen out of the positions of leadership in the struggle which they have earned by their courage, intelligence, militance, dedication, and ability.”

Her last and most pointed argument to the male leadership was that the exclusion of the movement’s Black women leaders could be fatal to the drive for civil rights. Tolerance for male chauvinism in a movement against white chauvinism, she wrote, only proved that every form of discrimination was connected to every other one, and that none of them could be defeated unless all of them were.

In 1963, no civil rights campaign can be permanently successful which does not stand foursquare for all human rights. Civil rights for Negroes cannot be won at the expense of rights of labor or rights of women or by ignoring the rights of the impoverished whites and the problems of the aged and handicapped…. [All] non-merit discrimination is immoral and should be made illegal.

The day after the March on Washington, Dorothy Height, Murray’s friend since their days together at the Harlem YMCA and now president of the National Council of Negro Women, presided over a meeting to consider how to respond to the absence of women on the March’s program. The outcome was the realization that, even in a civil rights movement, women would not get their own rights without taking them, an insight Murray later said was “vital to awakening the women’s movement.”

Three months later, when the group met again in New York City, Murray electrified them with a speech blasting civil rights leaders for the “bitterly humiliating” neglect of the movement’s women leaders, at the March and elsewhere. She framed that humiliation as the best possible evidence that “the Negro woman can no longer postpone or subordinate the fight against discrimination because of sex to the civil rights struggle but must carry on both fights simultaneously.” Her speech, Height said later, began “a great debate,” out of which came the concept of an “NAACP for Women,” which is how Pauli Murray would later describe her vision for a women’s movement to Betty Friedan.

Even then, antidiscrimination measures were circulating in Congress that would be incorporated the following year in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As initially drafted, Title VII of the act, which established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), outlawed job discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, and national origin. Two days before the House vote, however, “sex” was added to the criteria by Rep. Howard W. Smith, a Virginia Democrat who had previously been opposed to all civil rights legislation. Some felt he was only trying to undermine passage of the bill, but in fact a plurality of those who voted for it were Republicans, along with some southern Democrats.

When the new Equal Opportunity Commission received its first complaint, however—the first of several from female flight attendants—the agency’s chairman, Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., simply ignored it. He called the sex provision “terribly complicated,” and his executive director wrote it off as “a fluke,” an idea “conceived out of wedlock.” Nothing did more to mobilize women in the President’s Commission network to undertake a civil rights movement of their own. More in anger than frustration, Murray wrote to a close colleague on the Commission:

What will it take to arouse the working women of this country to fight for their rights? Do you suppose the time has come for the organization of a strong national ad hoc committee of women who are ready to take the plunge?

The time had indeed come, and leaders were in place, including Dorothy Height, Anna Arnold Hedgeman, and Ella Baker. All of them had known each other since the 1930s and had worked together in New Deal welfare programs, the Workers Defense League, and Randolph’s original March on Washington movement in 1941. Decades later, it was clear that they were pioneers of a new, more inclusive feminist movement, with a Wave to call their own.

In The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan wrote, “I never knew a woman, when I was growing up, who used her mind, played her own part in the world, and also loved, and had children.” To the young women who volunteered in the South to work in the civil rights movement, that statement made no sense. They knew Fannie Lou Hamer.

“Mrs. Hamer,” as they called her in a sign of respect, did not call herself a feminist. Until she was in her forties, she said, she had never even heard the word. In that, she was not unlike other women of her generation, for whom the term “feminist” was used mainly in the National Woman’s Party, and even there sparingly. Elsewhere, it was sometimes called “the f-word.”

Hamer had spent most of her life as a sharecropper on a cotton plantation in the Mississippi Delta, the deepest of the Deep South. The last of 20 children, she began picking cotton after school at the age of six. She was already a prize-winning student when she had to quit school after sixth grade to join her parents in the cotton fields full-time. From then on, her working day ran from first light to exhaustion, “from can to can’t.” The family often lived on meals of bread and onions, sometimes without the onions.

Like all Black sharecroppers, her family also lived under the threat of white violence, which could come anytime and out of nowhere. One of her strongest childhood memories was of her mother “getting on her knees to pray that God would let all her children live.” Every morning when they left the house to go to work, her mother brought along a pail covered by a cloth. Fannie Lou never knew what was in it until one day she managed to take a peek and saw a 9mm Luger. “No white man was going to beat her kids,” she remembered her mother saying.

Hamer’s activism for civil rights did not begin until she was almost 45 years old, but she had been practicing other forms of resistance for years. Her maturity, work ethic, and good arithmetic skills led the landowner to make her the plantation’s timekeeper, responsible for noting each field hand’s hours worked, their daily weight in cotton, and the money they had earned. In that role, she managed to resist the owner’s habit of cheating the workers by shaving down their debts to him and otherwise bending the books toward justice, somehow without detection. In that way and others, she worked to undermine the system by which plantation owners kept Black laborers in their debt. “I was rebelling in the only way I knew how to rebel,” Hamer said.

She got that spirit of rebellion from her mother. “There weren’t many weeks passed that she wouldn’t tell me… you respect yourself as a Black child, and when you get grown, if I’m dead and gone, you respect yourself as a Black woman, and other people will respect you.” In the Mississippi of the 1940s and ’50s, the corollary to self-respect was rage at the disrespect of others, and Fannie Lou got angrier and angrier as she grew from childhood to womanhood. “It’s been times that I’ve been called ‘Mississippi’s angriest woman,’ and I have a right to be angry,” she said. For years, she had been looking for something more than cooking the plantation’s books to “really lash out and say what I had to say about what was going on in Mississippi,” but even civil rights organizations were reluctant to do that. Without support, it would be worse than useless.

Her chance came in 1962, when the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee came to Sunflower County and her hometown of Ruleville, which made an especially tempting target for SNCC’s voter registration campaign because it had a Black majority, and only one in a hundred were registered to vote.

One night in late August, at the William Chapel Baptist Church in Ruleville, where Hamer worshipped and sang every Sunday, SNCC held a meeting to recruit volunteers. They finished their talk by asking willing volunteers to raise their hands. Very few went up, but Fannie Lou Hamer’s did—“as high as I could get it,” she wrote later in an autobiographical pamphlet for SNCC.

I guess if I’d a had any sense I’d a been a little scared, but what was the point of being scared? The only thing they could do to me was kill me, and it seemed like they’d been trying to do that a little bit at a time ever since I could remember.

Four days after signing on with SNCC, she and 17 others got into a school bus for the 26-mile drive to the county courthouse in Indianola, where they tried to register to vote and, as always, failed. In one of the common methods of disqualification, the registrar tested them on the most obscure passages of the Mississippi constitution. Hamer drew a blank when asked to explain the theory of “de facto” laws, which she said she knew as much about “as a horse knows about Christmas.”

As they started driving back to Ruleville, they were stopped by police, whose transparent excuse was that the color of the school bus was off. The driver was taken into custody and back to Indianola. As his passengers waited to see what would happen next, they began to talk about why they needed to be home, what was keeping their driver, what they would do if he never came back, what might happen if they were put in jail themselves. As the anxiety mounted, Hamer began to sing. One of her favorites was the gospel song “This Little Light of Mine,” inspired by Matthew 5:14–16: “Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your father in heaven.”

At moments of high tension like this one, at the March Against Fear in 1966, Fannie Lou Hamer had a way of quieting nerves and inspiring solidarity with a gospel song.

It was for moments like these that her voice was always remembered—a strong, low contralto that cut through tension like a sharp knife. Harry Belafonte, who sang with her many times, said he could not really describe her voice “as a voice” because it seemed to be more than that. It was “the voice of us all,” he said, a voice that “transcended all other considerations at the moment.” She sang songs everyone could sing, because they were the spirituals they sang together in church on Sundays and in the cotton fields every day. SNCC was committed to leaving local causes in the hands of local leaders, and they knew after the trip to Indianola that they had found one in Mrs. Hamer.

Her plain, no-nonsense approach to activism made the leaders of the more traditional NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference uncomfortable, which she did not mind at all. She had indelible memories of being degraded by Black men and civil rights leaders more educated than she. She was far from alone in calling the NAACP “the National Association for the Advancement of Certain People,” and that animus remained when she took on a leadership role with SNCC. Before audiences of the powerful and the powerless, she spoke as she spoke at home, in the vernacular of a sharecropper but with the fluency and power of her singing. “I don’t think there was a wasted hum when she sang,” Belafonte said, and she spoke the same way—directly, without a pause or second thought, never from notes, always from the heart.

By the time she got home from trying to vote, the owner of the plantation where Hamer had worked for 15 years knew what she had done, and he gave her an ultimatum: If she would not withdraw her attempt to vote, she could no longer live or work there anymore. After talking to her husband and their daughters, she left and never went back.

Other people on the bus to Indianola paid a price as well. The bus driver was fired because his mother was one of those who tried to register. Homes whose owners were known to have taken in Mrs. Hamer and the SNCC workers were sprayed with gunfire. A farmer pulled his truck alongside two SNCC workers and threatened to shoot them if they ever came near his land.

After that year’s harvest, her husband and daughters left the plantation to join her, but they had to leave Ruleville for a while because of threats against them. Perry Hamer could get only occasional work after that because of his wife’s activism, but in time friends helped them to get a small house in Ruleville, and from then on they subsisted on food surplus, charity from friends and movement allies, and her ten-dollar-a-week stipend from SNCC.

Ruleville’s infamous mayor Charles Dorrough did everything he could to make her life miserable. He tried to disqualify her from the federal food program. He called her to his office when she was two days late on her water bill, which was for $9,000. She said she had been wanting to ask him how she could owe that much since they weren’t home most of the time and didn’t have running water in the house. She fought inflated utility bills for years after that.

Despite everything, she kept up her activism with SNCC and others. She worked in the Citizenship School program of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which taught would-be voters what they needed to know to pass the registration tests and whatever else they wanted to learn, from reading the newspaper to filling out forms for money orders. While working to solve practical problems in her community, she attended leadership programs and spoke widely about the problems of Mississippi and the nation, and as she grew in recognition and influence she became an ever-larger target for retribution.

In the spring of 1963, Mrs. Hamer and other SNCC workers attended a Citizenship School in Charleston, South Carolina. On the way home, during a long layover in Winona, Mississippi, a few of them got off the bus to use the bathrooms and get something to eat. Practicing what they had learned, they sat down at the lunch counter. Then they waited. After some time, they got the attention of a waitress, who said, “We don’t serve n-----s.” Then the Winona police chief and a highway patrolman arrived and started poking them off their stools with billy clubs and telling them to get out. They left peacefully but then stood outside discussing what to do. When the officers saw them writing down license plate numbers, they came outside and put them all under arrest.

Hamer never completely recovered from the beating she took at the county jail in Winona, Mississippi. She suffered especially from being beaten repeatedly on areas where she had had polio as a child. After Winona, however, her activism only increased.

At the Montgomery County jail, they were taken to individual cells and then brought out to be beaten, one by one. The first was June Johnson, then 16. The other prisoners could hear her trying to reason with the police, saying the waitress had broken the law by refusing to serve them.

“What do you think we’re supposed to do about that?” one of the officers said.

“You all are supposed to protect us and take care of us.”

All they heard after that was Johnson’s pleading and crying, and the sounds of a long, loud beating, including the sharp cracks of a billy club against her skull. When they saw her as she was walked back to her cell, most of her clothes were torn off, her head was beaten in, her left eye was swollen shut, and there was blood all over her. After a few minutes the police returned to make her get rid of the evidence. They told her to strip in front of them, then to wash her clothes and wipe away all the blood from her body. They called in someone else to clean the blood from the floor, then brought out another SNCC worker, 30-year-old Annelle Ponder. As they beat her, they kept insisting that she say, “Yes, sir” to their questions, but she never did, and they kept beating her.

Then it was Hamer’s turn. They knew who she was and told her, as she later testified, “We’re going to make you wish you was dead.” They took her to a room where Winona’s police chief and the arresting officers were waiting. With them were two Black prisoners. One of them, who looked as if he had been beaten himself, was ordered to beat her with a blackjack. He protested at first, then began to do as he was told, and she began to scream. “That man beat me ’til he gave out,” she testified. The officer who took over focused the blackjack on her head. Then others joined in, beating her all over. When they began beating her left side and left leg, which had never recovered from the polio she had had as a girl, she tried shifting her feet to protect herself, and at that the other Black prisoner was told to sit on them. Then she used her hands and arms to try to take the blows, but the beating continued, and she continued screaming and crying until she was going in and out of consciousness. Then she was literally thrown back into her cell and “just lay there crying,” Johnson remembered. “All night we could hear her crying.”

The beatings of the others went on for hours. When SNCC workers came from headquarters to check on them, they were arrested and beaten as well. Two days later, without a lawyer present, each of them was convicted of disorderly conduct and resisting arrest and fined $100. Before they were released, two agents from the FBI turned up to investigate. They seemed suspiciously friendly toward the police and soon left. After that, Hamer and her fellow prisoners were forced at gunpoint to sign statements saying they were beaten not by police but by each other.

The police were right to worry about the U.S. Justice Department getting involved. On the day of the arrests, Julian Bond, cofounder and then communications director of SNCC, wired Attorney General Robert Kennedy about what was happening in Winona. Once they were released, the Justice Department filed suit to overturn their convictions and sued five of the police officers for depriving those arrested of their civil rights. Their trial at the federal court in Oxford, Mississippi, however, featured the usual jury of 12 white men, and, as expected, ended in acquittals.

On their release, Hamer was taken to a hospital in Greenwood, which sent her on to Atlanta because of the severity of her condition. Her recovery took months, and it left her blind in one eye and with serious kidney damage and an even worse limp than she had had before, but the beatings only fired her determination to change things.

Around this time, Jane Stembridge, a white seminary student who had been recruited as SNCC’s first full-time employee, wrote a note to herself: “I have been thinking about this. Mrs. Hamer is more educated than I am. That is—she knows more.” Watching Mrs. Hamer gave Stembridge an insight about herself: “I went into society…. And that is where I learned that I was bad…. Not racially inferior, not socially shameful, not guilty as a White southerner… not unequal as women… but Bad.” Stembridge was then in rebellion against the standards forced on her as “a good southern girl,” standards that she felt worked against feeling strong and whole. Hamer seemed to have no such problem, and Stembridge thought her distance from “society” had preserved her ability to be proud of herself. Without that sense of confidence, Stembridge wrote, “She couldn’t get up and sing the way she sings. She wouldn’t stand there, with her head back and sing!… She knows that she is good.”

To Stembridge and to other young white women from south and north, working for civil rights introduced them to a feminism different from their mothers’. They served local people for whom the civil rights movement was not just a good cause but a very personal fight for freedom. Their most impressive leaders were brave women, young and old, married and single, some of them raising children and working outside the home while defying the threat of racist violence every day to win equality for themselves, their family, and their community. To the daughters of Betty Friedan’s readers, the SNCC experience prompted less a “strange stirring” than an agenda.

As soon as she had recovered sufficiently from her wounds, Hamer redoubled her civil rights work, which took her into new, more ambitious forms of activism. In 1964, she dove into the voter registration project “Freedom Summer.” That spring, on a campus in Oxford, Ohio, she coached hundreds of student volunteers on how dangerous their undertaking was going to be, how far to go in resisting police, how to respond to white racists, and all the many things not to do. Her own story was warning enough for the volunteers, who were unpaid, 90 percent white, and most of them new to the South. She advised and comforted them all through that summer of violence, which began when the Klan and local police collaborated in the kidnapping and murder of three volunteers. The search for them clouded most of the summer, but their bodies were eventually found, and decades later, those old enough to be there could remember their names: James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner.

By the end of Freedom Summer, police had made a thousand arrests of civil rights workers and the local people who helped them. At least 67 churches, homes, and Black-owned businesses were bombed or burned out. By the end of the summer, there were only about 1,200 new Black voters in Mississippi, but national outrage over the violence of Freedom Summer led to two historic victories: It helped to convince President Lyndon Johnson to push through passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Even as Hamer worked to support the volunteers of Freedom Summer, she was also active in forming a new Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which tried to replace the state’s all-white delegation to that year’s Democratic National Convention. At that, President Johnson drew the line. When she was scheduled to make that argument in a televised meeting of the Credentials Committee, he called a newsless news conference so the networks would cut away from her. That proved worse than futile, however, since all three networks responded on the evening news that night by replaying her testimony, which included a graphic account of the beatings in Winona.

After that she focused her activism on poverty in the Delta, where 70 percent of the homes were no better than shacks, most had no indoor plumbing, and the median income for Black families was $456, at a time when the national poverty line was $2,000. Periods of near-starvation were not uncommon. Malnutrition was epidemic. She also worked with SNCC to start the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union, which led local field hands and domestic workers in a series of dangerous but ultimately futile strikes for better wages.

Her most ambitious program to address the sources of poverty was the Freedom Farm Corporation, which set out to rebuild the economy of Rulesville and Sunflower County from the bottom up. Freedom Farm initiatives included buying hundreds of acres of land and making them available to former sharecroppers and others. The organization developed animal-breeding programs to increase the meat supply. It bought homes to convert rents into mortgages and turn tenant families into homeowners. It built dozens of new houses, raising more than $800,000 in FHA loans to do it. Freedom Farm gave out student scholarships for vocational schools and college. It helped develop new local businesses, which included buying buildings for a sewing factory, a fashion shop, and a plumbing operation that could put in water lines and sewers. In the end, Freedom Farm helped more than 600 families get to the point where they could help themselves. Hamer hired a manager to run the day-to-day business while she approved and helped to design new projects and traveled all over the country raising money to pay for them. While doing all that, she won a lawsuit as the named plaintiff in a lawsuit to integrate the all-white schools of Sunflower County. That victory, 15 years after Brown, gave her the pleasure of escorting her daughter Vergie Ree into the previously all-white school in Ruleville.

Still, she was met more often by defeat than victory. In the end, Freedom Farms gave out more than it took in. She lost three races for local office, and in a race for state senator she lost by a margin so overwhelming she was probably right to call it fixed. She even failed to carry Ruleville. The Freedom Democratic Party was the only Mississippi delegation seated at the 1968 national convention, but by then Black women were no longer among the leaders. As Unita Blackwell recalled, the Party had “lost the truth… because all the guys were in again, the big wheels….”

That Hamer won any victories at all was a demonstration of fierce determination. That was tested when her 22-year old-daughter Dorothy Jean, the mother of an infant and a toddler, suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. Hamer was with her and rushed her to the nearest hospital, but she was refused admittance because she was Black. The next closest hospital turned her away for the same reason. By the time they found a hospital that would take her, they were in Memphis, 120 miles from home, and as they approached the front door, Dorothy died in her mother’s arms. Fannie Lou and her husband took in Dorothy’s two children. That was the year she started Freedom Farms.

In 1971, she became one of the first leaders of the National Women’s Political Caucus. In her inaugural speech she wanted them to know that she was more than just a feminist. In a way, her speech restated Pauli Murray’s letter to A. Philip Randolph the night before the March on Washington. To a group whose theme was “sisterhood,” she said women would never be sisters unless they joined hands in the cause of the Black man, “because nobody’s free unless everybody’s free.”

Years later, her comrade-in-arms Shirley Chisholm remembered that Hamer’s speech was “kind of harsh. A lot of women could not understand what [she was] railing about.” But Chisholm and other Black women at the conference backed her up, and Gloria Steinem resoundingly joined in. At the end of the day, the organization passed a measure pledging to support candidates both male and female, Black and white, but only those committed to eliminating the linked oppressions of sexism, racism, violence, and poverty.

A few months later, Hamer collapsed during a demonstration and was hospitalized for what was called a nervous breakdown. Later she lost a breast to cancer. She was never the same after that, but her legacy was secure, and she lived long enough to see it honored in a book of writings by Black women. The scholar who collected them saved Hamer’s for last. It was taken from a speech she made to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund that talked about the debt feminism owed to the civil rights movement. She talked about her empathy for white women, who had been put on a pedestal and given “this kind of angel feeling that you were untouchable.” That pedestal was going to be gone very soon, she said, and when that happened, white women were “gonna have to fight like hell, like [Black women] have been fighting all this time.”

She ended her speech with a kind of farewell to her generation of activists and an exhortation to the next one. It was the story of a wise old man, who was known for being able to answer even the most difficult questions.

So some people went to him one day, two young people, and said, “We’re going to trick this guy today. We’re going to catch a bird and we’re going to carry it to this old man. And we’re going to ask him, ‘This that we hold in our hands today, is it alive or is it dead?’ If he says, ‘Dead,’ we’re going to turn it loose and let it fly. But if he says, ‘Alive,’ we’re going to crush it.” So they walked up to this old man, and they said, “This that we hold in our hands today, is it alive or is it dead?” He looked at the young people, and he smiled. And he said, “It’s in your hands.”

That story comes at the end of more than 150 entries in Gerda Lerner’s groundbreaking collection of primary-source documents, Black Women in White America. There had never been a book like it. The title page read “edited by Gerda Lerner,” but it more accurately might have said “flung by Gerda Lerner,” because it gave the lie to all the university historians who had insisted there was not enough evidence that women, much less Black women, deserved a separate discipline of history. To find her sources, Lerner scoured old newspapers, public hearings, trial transcripts, libraries, files, and personal papers that she found gathering dust in churches, attics, local libraries, and courthouses all around the North as well as the South.

Her work accomplished its purpose. The year the book was published, after a struggle with faculty and administration at Sarah Lawrence that had gone on for years, she realized her dream of starting the nation’s first graduate program in women’s history. According to NYU professor Linda Gordon, her former student, the impact of Black Women in White America was “stunning, even thrilling…. A generation of historians of Black women felt empowered by that book.” One of them was Professor Darlene Clark Hine of Northwestern University, who never forgot seeing the book for the first time. She sat with it for hours that day, and she later called it a major influence on her career as a scholar.

For Lerner, the study of women’s history was her life of activism in its final form, successor to her move toward radicalism in Austria, her work for the Congress of American Women, and her advocacy of progressive causes in and out of the Communist Party. Her commitment to the field of women’s history was more than academic to her. She saw it as a way of building a better world. In the program she started at the University of Wisconsin, she required her doctoral candidates to produce public lectures on women’s issues, and presentations for primary and secondary school classes on women in sports, women in the workplace, women in politics. She saw scholarship as an agent of change.