As soon as he graduated high school in 1943, Medgar Evers enlisted in the Army. He saw combat from D-Day to the end of the war in Europe, including service with the famous “Red Ball Express.”

On February 12, 1946, after three years in the Army and the last 15 months in the Pacific, Isaac Woodard picked up his honorable discharge papers at Camp Gordon, Georgia. He had served with the segregated 429th Port Battalion in the Philippines and New Guinea until the end of the war. He enlisted as a private and came home as a decorated tech sergeant.

Once he had his papers, he boarded a public bus with other Black and white soldiers and a few local civilians. For the first time in three years, he was going home to Winnsboro, South Carolina, where his family had lived for generations and where his wife, Rosa, was waiting for him. They had married not long before he was drafted and had not seen each other since the day he left. He would not see her this day either, because it was his misfortune to be a Black man in full uniform, with sergeant’s stripes and medals, back in the unreconstructed Jim Crow South.

A large majority of the million-plus African American troops in World War II came home to the South, where Black soldiers’ homecomings were better known for insults, threats, and guns than the thanks of a grateful nation. Despite the cautionary example of Black GIs after World War I, who were given less than no credit for their service, the World War II generation thought this time would be different. The war had created bonds that crossed the color barrier, connecting Black soldiers to the people they fought for and those they fought beside. The memory of what that felt like—what General Colin Powell later called “a breath of freedom”—changed them, just as the unchanged racists in their unchanged nation expected it might.

At a stop for gas, Woodard asked the driver if he could get off and use the bathroom. Greyhound drivers were told to accommodate such requests, but this one did not. “Hell no, God damn it, go back and sit down. I ain’t got time to wait.” Woodard responded in kind—“God damn it, talk to me like I am talking to you. I am a man, just like you!” At that, the driver told Woodard to go ahead, but he did not leave it there. At the next stop, in Batesburg, South Carolina, the bus was met by the town’s entire police force, which consisted of Chief Lynwood Shull and Officer Elliot Long.

The driver told Woodard to get off the bus to talk to them. He had just started explaining himself when Shull told him to “shut up” and hit him in the head with his police baton, a special club that came with a head filled with metal for extra weight and a spring-loaded handle for force of impact. Shull then put Woodard under arrest, twisted his arm behind him, and started walking him to the town jail. When they rounded a corner, out of sight of the bus, Shull asked him if he had just been discharged from the Army. When he said, “Yes,” Shull started beating him again, saying the correct answer was “Yes, sir.” At that, Woodard fought back and managed to get control of the club, but just then Officer Long appeared with his gun drawn and told him to drop it, “or I will drop you.”

When Shull got his baton back, he beat Woodard with it harder than before, so hard he broke it and left Woodard briefly unconscious. When Woodard regained consciousness and tried to get to his feet, Shull began beating him again and dragged him to jail.

At some point during their struggle, Shull ground his baton precisely into each of Woodard’s eyes, blinding him for the rest of his life. It was a particularly eloquent brutality, suggesting that Woodard had forgotten or consciously violated the Jim Crow code that prohibited looking white people in the eye. In any case, Shull’s intent was clear, as a later ophthalmology report concluded: There was hemorrhaging and pus behind both of Woodard’s eyelids, but his nose was undamaged. The prognosis for the return of his eyesight was unequivocal: “hopeless.”

Before taking him from his cell the next morning, Shull wiped all the dried blood off his face, then walked him to the courtroom of Judge H. E. Quarles, who was also the mayor of Batesburg. Woodard was charged with “disorderly conduct.” He had no lawyer or witnesses with him that day, and the word of a Black man carried less than no weight against that of a police chief. As soon as Shull told the judge that Woodard had grabbed his police baton, the judge declared him guilty (“We don’t go for that kind of thing around here”) and said he could pay a $50 fine or serve 30 days in jail. Woodard had $44, the judge waived the $6, and with that he was free to go, except of course he was blind. On a doctor’s advice, Shull dropped him off at the Veterans Administration hospital in Columbia, South Carolina, where he spent the next two months. His wife left him as soon as she learned that he was blind, and when he was able to leave the hospital, his sisters picked him up and brought him to their father’s house in the Bronx.

What Woodard suffered after the war was not the worst violence that met African American soldiers, who came home hoping more for than just a breath of freedom. The betrayal of that hope prompted every response Langston Hughes imagined in 1951: It festered, it stank, it exploded, and it did so with special force because it had happened more than once before. After Emancipation in 1863, Black men enlisted for the Civil War by the thousands. Frederick Douglass heartily approved: “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is not power on earth which can deny that he had earned the rights to citizenship in the United States.” Reconstruction suggested he was right, but Lincoln’s successor and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan helped put a violent end to that.

When the U.S. entered the First World War, NAACP cofounder W. E. B. DuBois followed Douglass’s lead, urging African Americans to enlist—to “close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens” in order to demonstrate their patriotism, their courage, and the right to equal standing in American society. Once again, that hope was crushed by violence. Inspired by D. W. Griffith’s virulent The Birth of a Nation, the Klan swelled from thousands of members to millions, and the prospect of Black soldiers emboldened by their service—in the word of the moment, “biggety”—inspired a wave of racist violence. In 1919, Black men were lynched at a rate of one every five days. No victim was a more inviting target than the Black man in uniform, who was presumed to have slept with white women in Europe and so invoked the white supremacist’s nightmare vision of “social equality.” Among the first to return from the Great War to Blakely, Georgia, Pfc. Wilbur Little was met by a group of whites as soon as he stepped off the train. They forced him to strip off his uniform and warned him he would be killed if he ever wore it in public again. A few days later, he was found in uniform and murdered. For all the service and lives they gave in war, as one Black newspaper put it, “It seems that the Negro’s particular decoration is to be the ‘double-cross.’ ”

On the other hand, they came home trained for war. Between the spring and fall of 1919, race riots broke out in more than 20 cities in the North and South. The first outbreak came in Washington, D.C., where Black veterans created a security cordon around Howard University and occupied the rooftops of Black neighborhoods, waiting in ambush for a band of Navy sailors who had been on a days-long spree of drunken violence, snatching Black citizens from the street and lynching them for no reason at all. In that “Red Summer” of 1919 most of the riots were started by whites—in the North most often over jobs and housing, in the South to reinvigorate Jim Crow justice and shore up white supremacy. But Black veterans were not easily cowed, and they inspired in others the determination to use force in their fight for freedom and equality.

Twenty-seven years later, driven by the same anger over their scorned sacrifices, Black veterans of World War II set out to do the same.

Until the late twentieth century, the story of the civil rights movement was neatly bordered by the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. By the start of the twenty-first century, however, the historians Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Athena Mutua, Nikhil Pal Singh, and others called for retrieving a longer history of the movement. Reframed as the Black Freedom Struggle, that story included racial injustices and Black responses going back to the time of slavery and ahead to the present day.

One of the tensions resolved in this recast history was between nonviolent and violent resistance. In the classic Brown-to-Voting-Rights-Act timeline, they appeared to be hotly debated alternatives. In the longer view, nonviolence and armed resistance were joined in tactical alliance, which had a long history of its own. In the early 1900s, W. E. B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and untold numbers of other Black citizens accepted as fact that the Klan and other white terrorists would have to be met with force. Rosa Parks was six years old when the last Black veterans of World War I came home to Alabama, and she never forgot sitting up nights with her grandfather, who kept a shotgun on his lap, waiting for the Klan. She remembered him saying, “I don’t know how long I would last if they came breaking in here, but I’m getting the first one who comes through the door.” She stayed up with him because “I wanted to see it,” she said. “I wanted to see him shoot that gun.”

After World War II, Black veterans were among the leaders in every civil rights organization in the South, from Sgt. Medgar Evers, Sgt. Aaron Henry, and Cpl. Amzie Moore of the Mississippi NAACP and Sgt. Hosea Williams of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Georgia to Sgt. Robert F. Williams, who actually transformed a North Carolina chapter of the NAACP into a well-trained militia. All of these and many other leaders kept guns close at hand at all times. Even Martin Luther King’s home was sometimes transformed into an armory. Bob Moses, who led the work of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Mississippi, accepted armed self-defense as a fact of life. “Self-defense is so deeply ingrained in rural southern America that we as a small group can’t affect it,” he said. “It’s not contradictory for a farmer to say that he’s nonviolent and also to pledge to shoot a marauder’s head off.” Among Black veterans of World War II and in the longer history of the Black Freedom Movement, nonviolence without the threat of armed resistance to racist violence amounted to surrender.

As soon as he graduated high school in 1943, Medgar Evers enlisted in the Army. He saw combat from D-Day to the end of the war in Europe, including service with the famous “Red Ball Express.”

Two weeks after Woodard was blinded, a group of Black veterans in Columbia, Tennessee, took up arms against local police after an altercation between a white store clerk and a Black woman. The woman’s son, a recently discharged Navy veteran, intervened, and the ensuing scuffle ended when he threw the clerk through the shop window. The son and his mother were each fined $50 for disturbing the peace, but the clerk’s father insisted the veteran be charged with attempted murder.

That night, a white mob gathered in the business district where the incident had taken place. Black veterans were waiting for them, and they shot out the streetlights for cover. As four policemen approached, they were warned to stop, and when they kept coming the veterans opened fire, wounding all of them, only one seriously, but effectively eliminating half of the Columbia police force. In the next few hours, highway patrolmen and state guardsmen surrounded the area. The next morning, they moved in and indiscriminately arrested close to a hundred Black men, many more than had had any part in the standoff. Twenty-five were eventually charged with attempted murder, but only two were ever tried, and only one of them was convicted, thanks to the work of a defense team led by the NAACP’s Thurgood Marshall. When the trial was over, Marshall was followed and arrested by Columbia police on a patently false charge. They drove him to a remote, wooded area, and he was saved from lynching only by a brave colleague who followed the police car close behind and was ultimately able to drive away with him.

George Dorsey, a veteran of the war in the Pacific, also became a target just after his discharge. His crime was sheltering his brother-in-law, a sharecropper who got into an altercation that ended when he stabbed the son of his landlord. The son survived, but sometime later, Dorsey, the brother-in-law, and their wives were driven into a mob ambush, and all of them were murdered. “Up until George went into the Army, he was a good n----r,” one of the suspected assassins said later, “but when he came out, they thought they were as good as any white people.” No one was ever convicted or accused of the murders.

In an Oval Office meeting some weeks later, the NAACP’s longtime executive secretary Walter White and other Black leaders told the new president, Harry Truman, about the blinding of Isaac Woodard, the murder of George Dorsey, and other racially motivated attacks on Black veterans. Truman had been a captain during World War I in France, and the bloodshed he saw and casualties his unit took gave him a strong bond with the millions of soldiers who were just then returning from World War II. Truman was facing midterm elections at the time, and his polls were discouraging, especially in the South. Even so, he could not ignore what he heard. He was especially moved by the Woodard case, and he was never much for polls anyway. “I wonder how far Moses would have gone if he’d taken a poll in Egypt,” he wrote in a memo around that time. That midterm election turned out to be diastrous for Democrats in both houses, but there is no record that Truman ever regretted his decision to respond forcefully to what he heard that day.

After his meeting with the civil rights leaders, he wrote to his attorney general, Tom Clark, saying he was “very much alarmed at the increased racial feeling all over the country, and I am wondering if it wouldn’t be well to appoint a commission to analyze the situation.” Later, he announced just such a commission, and the Justice Department actually leveled criminal charges against Batesburg police chief Lynwood Shull. One year later, by then facing reelection himself, Truman released his commission’s ambitious, no-nonsense report, To Secure These Rights, and he gave his full support to its agenda, which included long-stalled anti-lynching legislation; abolition of the poll tax; laws to ensure equal access to housing, education, and health care; and an extension of the wartime Fair Employment Practices Committee, whose job was to guarantee equal access to jobs.

That won Truman few friends in his home state of Missouri or with southern Democrats in Congress. A letter from an old friend in Kansas City told him to “let the South take care of the N-----s… and if the N-----s do not like the Southern treatment let them come to Mrs. Roosevelt.”

Truman’s response was blunt. “The main difficulty with the South,” he wrote, “is that they are living eighty years behind the times and the sooner they come out of it the better it will be for the country and themselves.

I am not asking for social equality, because no such thing exists, but I am asking for equality of opportunity for all human beings and, as long as I stay here, I am going to continue that fight…. When a Mayor and a City Marshal [sic] can take a Negro Sergeant off a bus in South Carolina, beat him up and put out his eyes, and nothing is done about it by the State Authorities, something is radically wrong with the system.

For the 1946 midterm elections in the South, there was no issue more flammable than the right to vote. Two years before, in the case of Smith v. Allwright, the Supreme Court had declared the South’s all-white primaries to be unconstitutional. With the Great Migration to the North, the Black vote could now theoretically swing the electoral vote in 16 states. Inspired by the Supreme Court decision and the prospect of changing the racial balance of power, Black veterans led voter-registration drives all across the South. In Georgia, more than a thousand Black veterans engaged in a statewide, door-to-door campaign whose greatest ambition was to turn out the racist three-term governor, Eugene Talmadge. By the day of Georgia’s primary, July 17, they had managed to register 135,000 new Black voters, but thanks to intimidation, primary-day trickery, and illegal ballot purges, at least 50,000 Black votes were uncounted. Statewide, 98 percent of the African American vote went to Talmadge’s opponents, but he won anyway, even in 33 Georgia counties where Black citizens were in the majority. In 14 of those counties there were no Black votes counted at all. The first African American who had ever cast a primary vote in Taylor County, Army Pvt. Maceo Snipes, was shot two days later and died in the hospital, having been refused a transfusion because there was no “Negro blood” on hand.

In the even more racially inflamed state of Mississippi, Army Sgt. Medgar Evers was determined to vote in that year’s primary. He had been discharged only three months before, after a tour of duty that ran from D-Day to the Battle of the Bulge. Like others who survived the landing on Omaha Beach, he had waded through a sea of dead bodies, Black and white, toward a beach covered with casualties. Though he saw a great deal more bloodshed during his years in Europe, that memory would never leave him, and it fed his fury at the homecoming that he and his fellow veterans received. On his way home, with his discharge papers in hand and still in a uniform decorated for his service in combat, he had to sit at the back of the bus. On the same ride, for the first time since he had left the U.S. for France, he was refused service at a restaurant.

To understand just how deep the resentment and pain of returning veterans could go, James Baldwin wrote in The Fire Next Time,

You must put yourself in the skin of a man who is wearing the uniform of his country, who watches German prisoners of war being treated by Americans with more human dignity than he has ever received at their hands. And who, at the same time, as a human being, is far freer in a strange land than he has ever been at home. Home! The very word begins to have a despairing and diabolical ring. You must consider what happens to this citizen, after all he has endured, when he returns—home: search, in his shoes, for a job, for a place to live; ride, in his skin, on segregated buses; see, with his eyes, the signs saying “White” and “Colored” and look into the eyes of his wife; look into the eyes of his son; listen, with his ears, to political speeches, North and South; imagine yourself being told to “wait.”

Medgar Evers was beyond angry, and he was well prepared for a fight. He identified closely with the overthrow of colonial powers in Africa and actually began amassing an arsenal with his brother, Charles, for a war on white supremacy at home. In time, they abandoned the plan, but the anger remained.

For a Black man or woman, trying to vote in the Mississippi of 1946 was an audacious, dangerous, and likely futile undertaking. During the war, among the 900 registered voters in Evers’s hometown of Decatur, not one was Black. No Black person had even tried to vote there before. The Evers brothers had been able to register only because all GIs were exempted from the poll tax that year, but in the days leading up to the election, their parents were visited by white locals warning them to get their sons to stay away from the polls on Election Day. Their parents did not try to talk Medgar or Charles out of going, but they did let them know of the threats.

Walking to the courthouse to vote, Medgar and Charles shared the fondest hope of other Black citizens in Mississippi that day: to defeat the outspokenly racist two-term U.S. senator Theodore Bilbo. Bilbo knew that, of course, and he used it to incite his supporters to keep Black citizens from voting. As the election neared, in case they missed the point, he said: “I call for every red-blooded white man to use any means to keep the n----r away from the polls. If you don’t understand what that means you are just plain dumb.” The best way, Bilbo added helpfully, was “to see him the night before.” The Jackson Daily News said much the same in an Election Day story headlined simply, “DON’T TRY IT.”

When the Evers brothers and a few fellow vets reached the polling place that day, they were surrounded by a group of armed white men. Among them were a few they had known as boys. Another was the doctor who had delivered them. “Dr. Jack, I’m surprised at you,” Charles Evers said. “You the person that brought us here, and you’re standing there trying to deny me the right to vote.” The doctor’s response, he remembered, was that there were just “some things that n-----s ain’t supposed to do.” Evers and company regrouped, went home, and armed themselves, but when they returned the crowd arrayed against them had grown. Outnumbered and outgunned, they gave up and started walking home, accompanied all the way by a carful of white men, one of whom kept a shotgun trained on them. “Around town, Negroes said we had been whipped, beaten up, and run out of town,” Medgar Evers recalled. “Well, in a way we were whipped, I guess, but I made up my mind then that it would not be like that again, at least not for me.”

In that midterm election of 1946, Congress made a hard right turn. Democrats lost 54 seats in the House and 11 in the Senate, and Republicans took over Congress for the first time since FDR’s first election in 1932. Among the freshmen of the 80th Congress were Rep. Richard Nixon and Sen. Joseph McCarthy, whose witch-hunting would do so much to sharpen the edges of American politics. Yet even on that Election Day there were signs of hope.

Despite his call to threaten or murder would-be Black voters, Bilbo won reelection to a third term in the Senate by his narrowest margin yet. The NAACP led a campaign to have him disqualified for having conspired to disenfranchise Black voters, and, remarkably, a Senate subcommittee actually held several days of hearings on the issue in Jackson. Almost 200 Black veterans crammed the hearing room and were virtually all the witnesses against him, even though they knew their protest had almost no chance to prevail. Witnesses ostensibly on his side included county registrars who testified without embarrassment about how they prevented Black citizens from registering—by requiring white references, by holding them to a higher literacy standard than whites, by asking them to explain the most obscure clauses in the state constitution, or just by giving them “good advice” not to register. The outcome of the hearings was as expected, but as the historian Charles Payne noted, the Black veterans who turned out for the chance to testify represented “perhaps the most significant act of public defiance from Negroes the state had seen in decades.” And in the end, Bilbo never got his third term because he died before the new Congress began—a poetically just death, some observed, from cancer of the mouth. “Few would predict in the winter of 1946 that victory was in sight,” John Dittmer wrote in his luminous history of Mississippi’s civil rights struggle, Local People, “but in that crowded federal courtroom in Jackson the shock troops of the modern civil rights movement had fired their opening salvo.”

Another hopeful sign appeared that election day in Charleston, South Carolina, when, in the courtroom of Judge Julius Waties Waring, the police chief who blinded Isaac Woodard actually came to trial. What had happened to Woodard was by then a cause célèbre. He had done a national speaking tour sponsored by the NAACP, and his case had won the support of Orson Welles, who returned to the subject repeatedly on his popular radio show. The trial did not have to be held on that Election Day. The federal prosecutor assigned to the case actually petitioned Waring for a continuance, saying he had not had enough time to prepare. Waring denied his request, suspecting that the case would be dropped right after the election and had only been filed as a cynical play for Black votes. “I do not believe that this poor blinded creature should be a football in the contest between box office and ballot box,” he wrote to himself at the time.

Waring was a lifelong resident of Charleston, the son of one of its first families, whose ancestors settled there in the seventeenth century. He was also a power in the state Democratic Party, at least until his rulings began to diverge from community standards, especially with regard to its Black citizens. Waring’s later rulings were inspired in part by the Shull trial, which ended after the Justice Department’s local prosecutor actually apologized in his closing statement to the all-white jury, saying he was just doing his job. After Waring gave his instructions to the jury, he took a long walk, just to make sure the jurors would have to wait for their acquittal. When he returned, he announced the verdict from the bench without evident disgust, but his wife, who was sitting in the courtroom, broke down in tears.

From that case onward, Waring departed radically from his friends, family, and judicial peers, doing everything he could to dismantle the formal and informal ways in which Black citizens were denied their rights. He opposed the southern states’ attempt to bring back the white primary with his decision in Elmore v. Rice, and his shocking dissent in a key school desegregation case, Briggs v. Elliott, helped Thurgood Marshall frame his argument in Brown v. Board of Education. He also made changes in his court—hiring the first Black bailiff in South Carolina history, integrating his courtroom gallery—and in his everyday behavior, welcoming Black citizens to his home, his dinner table, and his circle of friends.

His rulings for civil rights cost him political allies, old friends, and even extended family members in Charleston. Both he and his wife became social outcasts and targets of the Klan, who firebombed their home one night as they ate dinner. They were not injured, but in 1952, when Waring retired from the bench, the couple moved to New York City, where they made their home for the rest of their lives. Waring returned to Charleston briefly in 1954 for an NAACP-sponsored celebration of the Brown decision but not again until he was buried there in 1968. His burial site was set apart from those of his family, and very few whites turned up for the service, but it was attended by a large crowd of African Americans.

By the time he tried to vote, Medgar Evers had already enrolled at Mississippi’s Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College, where he earned his BA in business administration and showed just how ambitious he was to do more. A scholar-athlete, he made dean’s list grades while being editor of the college newspaper and yearbook, playing varsity football and track, and becoming president of his junior class. While excelling at all of the above, he fell in love with a classmate, Myrlie Beasley.

Before he asked her to marry him, he told her all the reasons they should stop seeing each other—for instance, that she should keep her freedom and not tie herself down to an older man. She thought he was breaking up with her of course, and as he went on, she became furious. “How kind of you to think about me!” she said. “Is there someone else?” No, he said, “It’s for your benefit.” At that, she tore into him, and when she was finished, he produced a diamond engagement ring. She was still furious, but they were married shortly after.

His mother warned Myrlie that Medgar had always been “a little strange.” As a boy, she said, he had always been quiet and contemplative, always somewhere else, caught up in his thoughts. “I don’t want you to get upset with him if he pulls away from you,” Mrs. Evers told Myrlie,

because it won’t be because he doesn’t love you, but that’s just the way he is…. He’s my strange child…. He needs to be by himself at times…. Sometimes I look out the window and I see them all out there playing, and I look again a few minutes later and he’s nowhere to be found and I’d go out and I’d look for him and I’d find him in his favorite spot under the house. And I asked him… what’s wrong? [And] he’d say, “nothing, Mama, I’m just thinking.”

When they graduated in 1952, Evers was taken on as a protégé of T. R. M. Howard, a wealthy physician in the Delta town of Mound Bayou. In addition to his large medical practice, Howard owned a farm, a construction firm, and the Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company, where he gave Evers a job as a salesman and introduced him to the world of civil rights activism. The year before, Howard had founded the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL), a group that organized itself uniquely as a civil rights group with the means for self-defense and mutual protection. Because Black men who worked for whites could not join the RCNL without jeopardizing their livelihoods, Howard recruited Black veterans who owned their own businesses to run the organization. One of them was Amzie Moore, who owned a gas station in Cleveland. Another was Aaron Henry, a pharmacist with a drug store in Clarksdale.

He hired Evers to sell insurance to Delta sharecroppers, who like all agricultural workers were ineligible for Social Security benefits. During long days making sales calls and collecting premiums, he listened to their struggles, counseled them, and brought their stories home to Myrlie. Decatur was only 175 miles from his new home in the Delta, but the plantations were a world neither of them had ever known, a world where debt kept families in bondage to the owner of the land and where entire families, including young children, worked from before dawn to after dark. The sharecroppers’ children had no shoes, and their homes were not even shacks. Evers passed by many of them at first, thinking no one could possibly be living there. Families got their meager food and clothes from a local store, often belonging to the plantation owner, where they bought on the “furnish” they were given at the start of the growing season. At the end of the season, their “share” would often be calculated at whatever would keep them short of paying it back. Many were illiterate and bookkeeping was loose, so the sharecroppers’ debt could be whatever the plantation owner said it was. In any case, they were in no position to argue, since there were always other Black families willing to take their place. The slightest sign of self-assertion could lead to a beating, and failed escapes could lead to the end of a rope.

After that first summer of 1952, with Howard’s approval and despite the risks, Evers began spending less of his time selling insurance and more of it helping sharecroppers escape through Memphis to the North by various ingenious means, once even in a casket. He volunteered with the NAACP to sign up new members, at first with very little success, but over time he, Amzie Moore, and Aaron Henry managed to revive the chapters in Mound Bayou, Cleveland, and Clarksdale respectively.

Inspired by Jomo Kenyatta’s defiance of colonial forces in the fight for Kenya’s sovereignty, Evers began to fantasize again about forming a secret army of Black guerrillas in the South. At the end of 1952, Myrlie was pregnant with their first child, and he wanted a son he could name Kenyatta. He got the son in July 1953, but Myrlie named him Darrell on the birth certificate, moving Kenyatta to his middle name.

By then, she wrote later, her husband had become radicalized, at least by Mississippi standards at the time. One night at a meeting of the RCNL, he declared his intention to integrate the law school at the University of Mississippi—nine years before James Meredith finally managed to integrate Ole Miss, and then only with the aid of federal troops. Over the objections of his wife, her parents, and his own, Evers pursued admission to that bastion of the white South relentlessly. His assault made headlines in both white and Black newspapers, with special note of the fact that the NAACP’s top lawyer, Thurgood Marshall, represented him in the attempt. The process dragged for more than a year as university officials manipulated the admission criteria to meet their desired end, but his persistence in the face of every barrier and threat brought him to the attention of the NAACP’s national leadership. It also got the attention of the FBI.

Then, in the spring of 1954, the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education ordered the South’s “separate but equal” schools to be integrated, and the white South’s reaction verged on hysteria. Two months after “Black Monday,” as the date of the first Brown decision came to be known in the states of the old Confederacy, 14 men met in Indianola, Mississippi, and started the first White Citizens’ Council, a Klan without robes, which spread quickly across the South and beyond. Eventually the State of Mississippi covertly funded its state council, whose gentler methods of foiling integration included tactical firings, calling in loans, and boycotts of Black-owned businesses. The measures most feared, taken in concert with the Klan, were shootings, firebombings, rape, and lynching.

Before this, the NAACP had been reluctant to have a presence in Mississippi because of the danger, but the upsurge in race-motivated crime also opened new opportunities for litigation. Five months after the Brown decision, Evers was rejected by Ole Miss on the basis of admission requirements newly invented for that purpose, but because of the courage he had shown in his campaign, he was appointed the NAACP’s first field secretary in Mississippi. His responsibilities included building up the state’s branches, reporting crimes against Mississippi’s Black citizens to NAACP headquarters, and investigating the crimes as needed. That of course made him a target of the Klan and the White Citizens’ Councils. After that he carried a .45 revolver with him when he traveled around the state and slept with a shotgun at the foot of his bed. He also built up a small armory at home to protect his family in the event of attack. T. R. M. Howard’s property had by then become an arsenal, and Amzie Moore’s house in Cleveland was another one. At times of tension, their homes were lit up like daylight all night long.

Evers opened the NAACP’s headquarters in Jackson in January 1955, at the start of never-ending days trying to do the impossible. One of his jobs was to convince Black victims to bring charges against white rapists, vigilantes, and murderers: in other words, to put their jobs, livelihoods, and lives on the line as soon as their names turned up on the NAACP’s membership rolls, which were published regularly in local newspapers as “a public service of the Citizens’ Council.” And all he could promise in return was the NAACP’s legal support in cases with little chance of winning. Evers’s job also included circulating petitions calling for school desegregation. Not surprisingly, most of those who signed withdrew their names after threats of economic or violent retaliation. In Yazoo City, for example, 51 of the 53 people who signed such a petition withdrew their names. The other two left the state.

What bothered Evers more than those who feared the consequences were the quislings, the Blacks in white pockets, who accepted “the way things are” and said that nothing could be done about it, that whites had always won and always would. Since the Supreme Court had now clearly denied that, in Brown and related cases, Evers considered this complacency a kind of racial treason.

The Brown decision met a wall of official defiance in the South even before the second decision in the case, which defined the standard for progress in implementation as “all deliberate speed” and called for “a prompt and reasonable start.” Two months before that, more than a hundred southern members of Congress had signed what came to be known as the Southern Manifesto, which promised to defy the attempt of any branch of the federal government to override state laws on segregation. That brought “deliberate speed” to a dead stop. Two years after Brown, there was not a single integrated school in eight southern states.

At the same time, across the South, the White Citizens’ Council and the Klan mounted ever more determined attacks on civil rights initiatives and the NAACP, which shrank dramatically as its members’ homes were firebombed, whole neighborhoods were burned out, and civil rights activists were tortured and killed. Preachers and schoolteachers were beaten and murdered just for speaking well of integration. It was a time of cross burnings and night riders, a virtual 1950s remake of The Birth of a Nation, complete with the Klan’s vivid, self-induced fantasy of rapacious Black men hungry for white women.

By the time Evers opened the NAACP headquarters in Jackson, Mississippi, civil rights activism focused on racial violence and the registration of Black voters. One of Evers’s branches was in Belzoni, where the most prominent members were the Rev. George Lee and branch president Gus Courts. Lee was the first Black man since Reconstruction to become eligible to vote in that county, and between 1953 and 1954 he and Courts managed to get as many as a hundred more Black men on the rolls. None had yet managed to vote, however.

One afternoon in April 1955, after another conversation with Courts about how to change that, Lee said he had just been warned in writing to take his name off the rolls, or else. He had been warned before, but never in writing, and he told Courts he had “a feeling” that things were about to get violent. Late that night, as he was driving through Belzoni’s Black neighborhood, he was hit twice by a shotgun. His car ran out of control and crashed into a shack. He managed to crawl out of the car, and a taxi driver who heard the shots came to rescue him, but he died before he reached the hospital. The next day, Courts was told face-to-face that he would be next. His response was to accompany 22 would-be Black voters to the county courthouse to ask for absentee ballots, the safer way to vote. He was shot sometime later but not killed, and with the NAACP’s help, he moved to Chicago.

Not long after that, another Belzoni activist, Lamar Smith, walked out of the Lincoln County Courthouse, where he was teaching Black voters how to fill out absentee ballots. He was shot and killed on the courthouse’s front lawn. There were dozens of witnesses to the shooting, including the local sheriff. Though the FBI investigated all the murders, no one was ever charged, much less convicted of the crimes.

Evers was still investigating Smith’s death when, in the tiny Delta town of Money, Mississippi, 14-year-old Emmett Till bragged to some friends about having a white girlfriend back in Chicago. He said he wasn’t as scared of that as they seemed to be, so they challenged him to talk to the pretty young white woman behind a store counter. Apparently he did, but it was never quite clear just what he said or what happened there. The woman, Carolyn Bryant, testified to a grand jury that he had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities. (Decades later, she confessed that she was lying about that.) She also claimed she had said nothing about the event to her husband, but someone must have said something, because he responded in the worst southern tradition. He and his half-brother found Till, tortured him, tied him up, weighted him down, and threw him to his death by drowning in the Tallahatchie River.

The Emmett Till case presented Evers with his greatest challenge to date. The first was simply managing to keep the case alive when local authorities were determined to make it go away. Evers gathered evidence, found witnesses, identified suspects, and laid the basis for a prosecution. In the end, the grand jury refused to issue indictments, and a few months later, confident that they would never be brought to trial or charged again, Till’s murderers sold their vividly appalling account of the crime to Look magazine.

Months before it was published, however, Evers had transformed Emmett Till from the pitiful victim in a sensational story to the case in point for a historic reckoning, thanks in no small part to a photo. He had seen the effect of an open casket at the funeral of Rev. Lee, where people could not mourn without witnessing firsthand the brutality of his murder. As a result, he persuaded Till’s mother to leave her son’s casket open to mourners and to let in a few photographers, including one from Jet magazine. To the nation and around the world, David Jackson’s picture of Till’s wrecked, bloated body became an icon of America’s original sin.

The Till murder only tightened the spiral of racial violence in Mississippi. Membership in the state’s White Citizens’ Council swelled to 60,000 members, Klan activity surged, and Evers and other RCNL members joined hands in a virtual paramilitary force. T. R. M. Howard began sleeping with a machine gun, his home became an armory, and guards accompanied him as he embarked on a nationwide speaking tour to spread outrage at the murders in Mississippi and to raise a public outcry for some federal response.

Two weeks after the grand jury refused to indict Till’s killers, Howard’s tour reached Montgomery, Alabama, where he spoke to a mass meeting at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. The new pastor, the 26-year-old, as yet unknown Martin Luther King Jr., was there, and so was Rosa Parks, by now a seasoned investigator for the NAACP and no stranger to the most awful forms of racist violence. Howard and others spoke about the murders of Rev. Lee, Lamar Smith, and others, but Parks later remembered being particularly “disgusted” by what she heard about Emmett Till that night. Four days later, on her way home from work on the night of December 1, 1955, she kept her seat on the bus—not because she had sore feet, as the story sometimes went, but because she had had enough. As Dr. King put it on the first night of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, in his informal inauguration as leader of the civil rights movement, “There comes a time when people get tired.”

Drafted by the Army too late to fight in World War II, Robert F. Williams enlisted in the Marine Corps ten years later. His only battles then were with his commanding officer, but he learned combat skills he would deploy against the Klan back home.

Around the time Emmett Till was murdered, Robert F. Williams had just been dishonorably discharged from the Marine Corps after a fight with his commanding officer. It was his second tour of duty, this one his solution to a long period of unemployment. He had been drafted almost a decade before, but he started his service just a month before Hiroshima, and he was mustered out within the year. By the time he joined the Marine Corps, it was desegregated in theory but not yet in spirit, and Williams’s instinctive response to racial insult was to fight. As a result, that two-year stint was a series of verbal and physical confrontations that earned him months of brig time and other disciplinary actions until he was finally booted out.

Between tours, back home in Monroe, North Carolina, after V-J Day, he and some fellow veterans went to war with the Klan. A boyhood friend of theirs, Bennie Montgomery, had gotten into a fight that left his landlord dead. Arrested and spirited away by authorities to protect him from a lynch mob, he was convicted of murder, executed, and returned to Monroe for burial. When the Klan made it known they were coming for the body, Williams recruited his friends to make a stand outside the funeral home and stop them. The gunfight never happened because when the line of cars filled with Klansmen drove up, they faced 40 Black men with rifles and just kept driving. “That was one of the first incidents,” Williams wrote later. “That really started us to understanding that we had to resist, and that resistance could be effective if we resisted in groups, and if we resisted with guns.”

By the time Williams was released by the Marine Corps and returned to Monroe, however, the local White Citizens’ Council had managed to reduce the local NAACP membership to six brave souls—and as soon as they admitted Williams, five of the six quit. The one who stayed was a World War I veteran named Dr. Albert Perry. A militant advocate for civil rights, Perry was already a prime target of the Klan. Williams made him his vice president and began looking for members.

The NAACP’s most common target for membership was the Black middle class, but Williams began at the town’s pool hall and barber shop. His recruits were “laborers, farmers, domestic workers, the unemployed and any and all Negro people in the area,” he wrote later. He also applied to the National Rifle Association to form a local shooting club. Its first members were his fellow veterans, including three of the men who had stood beside him to protect their friend’s body from the Klan. He dubbed Monroe’s newest NRA chapter the Black Armed Guard. He needed that core of veterans, he said, because he needed people “who didn’t scare easy.”

In another cycle of progress and violence, the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott at the end of 1956 encouraged more Black activism, which in turn invited more action by the Klan. In Monroe, the worst of the trouble began in the summer of 1957, when yet another Black child drowned in yet another local swimming hole because the one public pool was for whites only. The city refused to set aside even one day a week for Black children to use the pool, arguing that the water would have to be drained and replaced each time they used it. So Williams and Perry organized protests, which lost them the few white supporters they had.

Some of Monroe’s white citizens drew up a petition declaring that both Williams and Perry should be forced to move out of Monroe “with all deliberate speed,” having “proven themselves unworthy of living in our City and County.” Carloads of Klansmen began shooting their way through Black neighborhoods, taking especially careful aim at Williams’s and Perry’s houses. The Klan caravans were invariably preceded by police cars—just to keep order, said the chief of police, who was a Klan member himself. Williams, Perry, and others in the chapter received regular death threats as Klan membership and attendance at Klan rallies enjoyed a new growth spurt. “A n----r who wants to go to a white swimming pool is not looking for a bath,” Klan leader Catfish Cole told one such rally. “He is looking for a funeral.”

A telephoned bomb threat to Perry’s wife when he was at an NAACP meeting was the turning point. The meeting quickly adjourned, members went home to grab their guns, and after that they guarded Perry’s home 24 hours a day. Eventually their number grew to 60 men, and when the next Klan motorcade came to shoot up Perry’s house, they faced a withering barrage from makeshift fortifications and sniper positions. “We shot it out with the Klan and repelled their attack,” Williams said, “and the Klan didn’t have any more stomach for this type of fight. They stopped raiding our community.”

Decades later, B. J. Winfield, one of Williams’s oldest veteran comrades in Monroe, talked about the effect of his leadership, that night and later:

The Black man had been thinking it all the time, but too scared to say it, scared to do anything. Rob Williams, after he come out of service, we thought he was talking too much. But after we found out he was getting it from the big book—I mean, it was our rights—then we went with him. After we seen him do all these things and accomplish these things, we said, “Well, he must know what he is talking about.”

Not long after Medgar Evers gave up trying to integrate higher education in Mississippi, Clyde Kennard of Hattiesburg tried it again. He too was a veteran, having enlisted in the World War II Army as soon as he graduated high school. By the time he got to Germany the war was over, but his seven years in uniform went on to include service as a combat paratrooper in Korea, where he earned a Bronze Star and other decorations. After his discharge, he enrolled at the University of Chicago as a political science major but had to withdraw before the end of his junior year, when his stepfather died. At that, he returned to Hattiesburg to help his mother start a small chicken farm on land he had bought for her with savings from his wartime pay.

Kennard’s time in the military had been relatively free of the problems faced by other Black soldiers. By the time of the German occupation, Black soldiers in Germany actually had some useful benefits, including access to secondary school classes that would serve them well in the peacetime job market. Part of Kennard’s service in Germany was to teach a course in democracy to young Germans as part of the “denazification” program, and by the time he got to Korea, Truman’s desegregation order had begun to take effect, mainly because of the sudden need for a massive buildup of troops. The post–World War II military had shrunk to 500,000 worldwide, when more than a million would be needed in Korea alone. Training bases in the U.S. were forced to confront the fact that keeping parallel units was going to be all but impossible and so began to integrate the trainees, in bunks and mess halls as well as in classes and drills. To the pleasant surprise of Gen. Omar Bradley, first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the transition turned out to be virtually painless, and by the end of 1951 the entire U.S. military was being desegregated.

When he returned to Hattiesburg in 1955, Kennard was a mature, accomplished 28-year-old college student, but he had not lived in Mississippi since he was 12 years old. That was when his mother, for the sake of his education, had sent him to live with an older sister in Chicago. To finish his senior year of college, Kennard decided to apply to Mississippi Southern, which was just a few minutes’ drive from home. Given the volume of correspondence between him and the college, he clearly expected reason to prevail, but Southern, like Ole Miss, had been segregated since its founding.

For four years, Kennard kept applying, and the college kept inventing new reasons why he could not be admitted—changing the rules, rejecting him on spurious grounds, making false claims meant to disqualify him, and portraying him as a disruptive malcontent. By the standard of the day, he had encouraged that charge. He had tried to register to vote. He lodged a complaint when a Black school closed near his home, forcing the children to travel 11 miles to another school. He had been to NAACP meetings.

In 1959, the college president, a committee of Black leaders, and even the governor of the state met with him to urge him to give up, but he would not, and Southern had run out of reasons to deny him admission. At that point, his insurance company canceled his policy, his mortgage company foreclosed on his farm, and state investigators searched for dirt in every corner of his past, without success. Finally, the head of the Hattiesburg White Citizens’ Council suggested another solution: “Kennard’s car could be hit by a train or he could have some accident on the highway, and nobody would ever know the difference.”

Instead, he was framed as an accessory to the theft of five bags of chicken feed worth $25, a felony that would disqualify him for admittance to Southern. The real thief, who testified that Kennard had put him up to it, got probation, but the judge gave Kennard the maximum sentence: seven years at hard labor. Evers was quoted in the press calling the verdict “a mockery of justice,” for which he was cited for contempt of court, fined $100, and sentenced to 30 days in jail. Evers’s conviction would be overturned, but Kennard’s was not, and in November 1960 he began serving his sentence at Mississippi’s infamous state penitentiary, Parchman Farm.

Kennard had been working six days a week in Parchman’s cotton fields for almost a year when chronic stomach pains became increasingly severe, then debilitating. At that, he was sent to a hospital in Jackson, where the pain was traced to a lesion in his colon that was presumed to be malignant. His chance of living another five years was estimated at 20 percent, which turned out to be optimistic. No treatment was prescribed. He was returned to Parchman and to his work in the fields. As he continued to weaken and lose weight, guards made his fellow prisoners carry him out to the field and back every day.

Evers was his close friend by then and led the campaign to free him. One night he was to speak about the case at an NAACP dinner, but he had just been to see Kennard’s mother, and as he began to talk about his friend, he had to stop. “Sitting next to him at the head table, I could tell he was choked with emotion,” Myrlie remembered. “I prayed he’d be able to continue. Medgar had always looked on crying as a weakness in men. Over and over he had told Darrell, ‘Men don’t cry.’ Regaining control, he started again, then stopped. It happened three times. Finally tears streamed down his face as he spoke, and he just gave way.” The audience began to sing a spiritual to cover his grief.

Robert Williams’s breaking point came at the courthouse in Monroe in the spring of 1959. He was a national figure by then, renowned for his armed standoffs with the Klan. During speaking and fundraising tours in the north and south, he had made important allies among civil rights activists, including Malcolm X, who invited him to speak at his Nation of Islam Temple No. 7 in Harlem. Later, Williams proudly quoted Malcom’s introduction: “Our brother is here from Carolina, and he is the only fighting man that we’ve got, so we have to help him so he can stay down there.”

Up to then, Williams had advocated nothing more than armed self-defense. Even that made him controversial at a time when nonviolence was the defining tactic of the civil rights movement, but after witnessing court proceedings that day, he crossed a line.

The first case concerned a Black housekeeper at the Hotel Monroe who had been thrown down a flight of stairs by a white guest. The other was the case of another white man, Louis Medlin, who was accused of trying to rape a Black woman, then eight months pregnant, in front of her five young children. Several of the women in Williams’s NAACP chapter told him that Medlin should be killed before he went to trial because, as awful as his crime was, he would never be convicted of it. Williams told them that if he resorted to that kind of violence, which amounted to lynching, he would be “as bad as the white people.”

Black women packed the courthouse that day. The first case was dismissed, as they knew it would be. The defendant had not even bothered to be in court, knowing in advance the charges were going to be dropped. In the rape case, Medlin’s wife was seated at the defense table beside her husband. As Williams swore in testimony years later to the Senate’s Internal Security Subcommittee, the victim of the crime and the women in the courtroom that day had to listen to Medlin’s lawyer argue this:

“Your Honor, you see this pure white woman, this pure flower of life, God’s greatest gift to man, this is Louis Medlin’s wife…. Do you think that he would leave God’s greatest gift to humanity, this pure flower, for that.” And then he pointed to the Black woman as if she [was] on trial. She broke down and started crying….

As expected, after a brisk trial and a few minutes out of the courtroom strictly for show, a unanimous white-male jury acquitted Medlin. With that, the women who had wanted him killed before trial turned on Williams, saying he was responsible. A wire service reporter nearby heard his response: The time had come for African Americans in the South to “meet violence with violence.”

That set bells ringing in newsrooms across the country: “NAACP Leader Urges ‘Violence.’ ” Within hours, Williams got a telegram from Roy Wilkins suspending him as an NAACP official, but Williams became only more convinced of his position and articulated it in interviews with reporters for newspapers, magazines, and television stations.

A decade later, he explained himself in testimony to the Internal Security Subcommittee, which was still run by the shrinking segregationist remnant in Congress. The chair was Strom Thurmond, and its members included former Klansman Robert Byrd of West Virginia and Sam Ervin of North Carolina, author of the “Southern Manifesto.” Williams was questioned by the subcommittee’s chief counsel, J. G. Sourwine.

The election of President John F. Kennedy in November 1960 marked a hopeful end to the 1950s. By then, school integration had come to Little Rock and other cities in the South, raising hopes that the promise of Brown, if not yet realized, someday would be. A new generation of civil rights activists had emerged by then as well: The lunch-counter sit-in by students in Greensboro, North Carolina, in February 1960 prompted a wave of sit-ins in every Southern state, the founding of SNCC, and the progressive political agenda of a new generation.

Even then, to Evers’s frustration, national leaders of the NAACP continued to resist the urge to activism among its youth councils, especially in Mississippi. Evers disagreed diplomatically, saying that although a sit-in might be unwise, “some form of protest was necessary” when “everyone else is protesting Jim Crow.” Soon after that, 200 Black students circulated handbills calling for a boycott of white merchants on Capitol Street, who would not hire Black workers and treated Black customers with disrespect. Aaron Henry undertook a similar boycott in Clarksdale. Like Henry, Amzie Moore, who led the Cleveland chapter, was tired of waiting for the NAACP and saw the future in SNCC. “Nobody dared move a peg [in the NAACP] without some lawyer advisin’ him,” he told the journalist Howell Raines later, but “SNCC was for business, live or die, sink or swim, survive or perish. They were moving, and nobody seemed to worry about whether he was gonna live or die.” Evers was diplomatic enough not to let headquarters know he felt the same way, and it hurt that he could lend such activism only tacit support.

On March 27, 1961, nine students from the NAACP’s youth council at Tougaloo College staged a sit-in at Jackson’s segregated public library. In short order, they were arrested for “breaching the peace,” and as they sat in jail overnight waiting for bail to be posted, they became a story, headlined the “Tougaloo Nine.” The next day, students at Jackson State boycotted classes in solidarity and marched toward the jail, where they were met by police who drove them back with clubs, dogs, and tear gas, another trigger for their fellow activists as well as the press.

The impact of the library sit-in exceeded Evers’s greatest hope. At trial, the nine were fined $100 each and given suspended sentences of 30 days in jail. That night, more than a thousand Black citizens turned out to show their support for the Tougaloo Nine, including parents who had previously told their children not to get involved in “that mess,” as civil rights protest was sometimes called. A few days later, the NAACP’s national headquarters joined in, authorizing an all-out campaign called “Operation Mississippi.” After that there were student-led anti-segregation protests at every sort of public facility in the state, from the swimming pools of Greenville and the movie theater in Vicksburg to the Clarksdale train station and the public zoo in Jackson.

And then, in May 1961, came the first Freedom Riders, two buses full of activists, white and Black, most of them young, determined to test a recent Supreme Court decision in Boynton v. Virginia, which made segregation of public buses and bus terminals unconstitutional. Starting out from Washington, D.C., and bound for Jackson, the first 13 Freedom Riders made it only as far as Anniston, Alabama, where they were met and beaten by a mob of Klansmen. As the bus’s tires were being slashed, the driver sped away, but carloads of Klansmen followed until flat tires stopped the bus. Klansman then surrounded it, broke open windows, and threw in a firebomb that forced out all the passengers for the beating of their lives. The Klansmen then went back to get the second bus, leaving their victims writhing and watching their bus burn. The second busload took their beatings in Anniston but met an even more vicious mob in Birmingham, where they were beaten by Klansmen organized and supervised by Birmingham’s infamous commissioner of public safety, Bull Connor, who had made sure no police would be there when the bus arrived. This gang went after the riders with iron pipes and baseball bats while Connor looked on.

The call for help went out to Attorney General Robert Kennedy and activists from SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), who began pouring in to take over for the original Freedom Riders. Kennedy sent in an assistant, John Siegenthaler, to investigate and advise them, but another mob met the Freedom Riders when they arrived in Montgomery, and Siegenthaler was among those left lying unconscious. Kennedy then sent in federal marshals, but only enough to guard the church where Martin Luther King Jr. was speaking, while a crowd of some 3,000 whites surrounded the building, harassing and attacking Black audience members as they came and went, while local police just watched.

Given all that the Freedom Riders could face on the next stops before Jackson, Kennedy called for a “cooling-off period,” but CORE’s James Farmer refused. Black Americans had been “cooling off for a hundred years,” he said, and the Freedom Rides continued.

Over that summer and fall, wave after wave of Freedom Riders drove through Alabama and Mississippi, taking more beatings and filling the jails along the way. At one point there were hundreds of Freedom Riders in Parchman Farm alone. One was John Lewis, the young future president of SNCC. Another was a young Howard student who would succeed him in that role, Stokely Carmichael.

By that fall, Evers was plainly suffering from overwork. Negotiating with NAACP headquarters, coordinating actions with CORE and SNCC, and helping a constant stream of people into his office who needed help of some kind, all while investigating murders and demonstrations where people were beaten and shot: He was putting in 18-hour days and drowning. His successes were also making him an ever larger target of the Klan, and he began to talk openly with Myrlie about being assassinated. Around that time, Myrlie told him he should get himself a new suit, and he said he did not think he would have time enough left to wear it.

That summer, SNCC’s James Forman was worried less about Evers in Mississippi than Robert Williams in North Carolina. By August 1961, SNCC had sent some of its volunteers from Mississippi and elsewhere to set up pickets around the courthouse in Monroe, demanding that the city desegregate all public facilities. Every day, the demonstrators attracted a growing and ever more threatening crowd of white onlookers. Soon, picketers were being singled out and beaten. Police arrested only those who fought back, while Monroe’s chief of police stood by watching. As the picketers walked home at the end of each day, carloads of Klansmen followed them, throwing bricks and bottles, brandishing weapons, and shouting death threats.

On Sunday, August 27, some 2,000 whites were waiting for the picketers outside the courthouse and attacked as soon as they began to arrive. Those who got away fled to Williams’s neighborhood, which was quickly fortified. Dozens of rifles, two machine guns, and other weapons were handed out; snipers climbed trees; sentries were posted; and barricades went up. When Williams called the police chief for help, as witnesses overheard and as he later testified to the Senate subcommittee, the response was: “Robert, you have caused a lot of race trouble in this town. Now state troopers are coming, and in thirty minutes you’ll be hanging in the courthouse square.”

That was the night Williams, his wife, and their three sons fled Monroe. He thought their time away would be temporary, a cooling-off period, but the chief confected criminal charges, and they did not return for seven years.

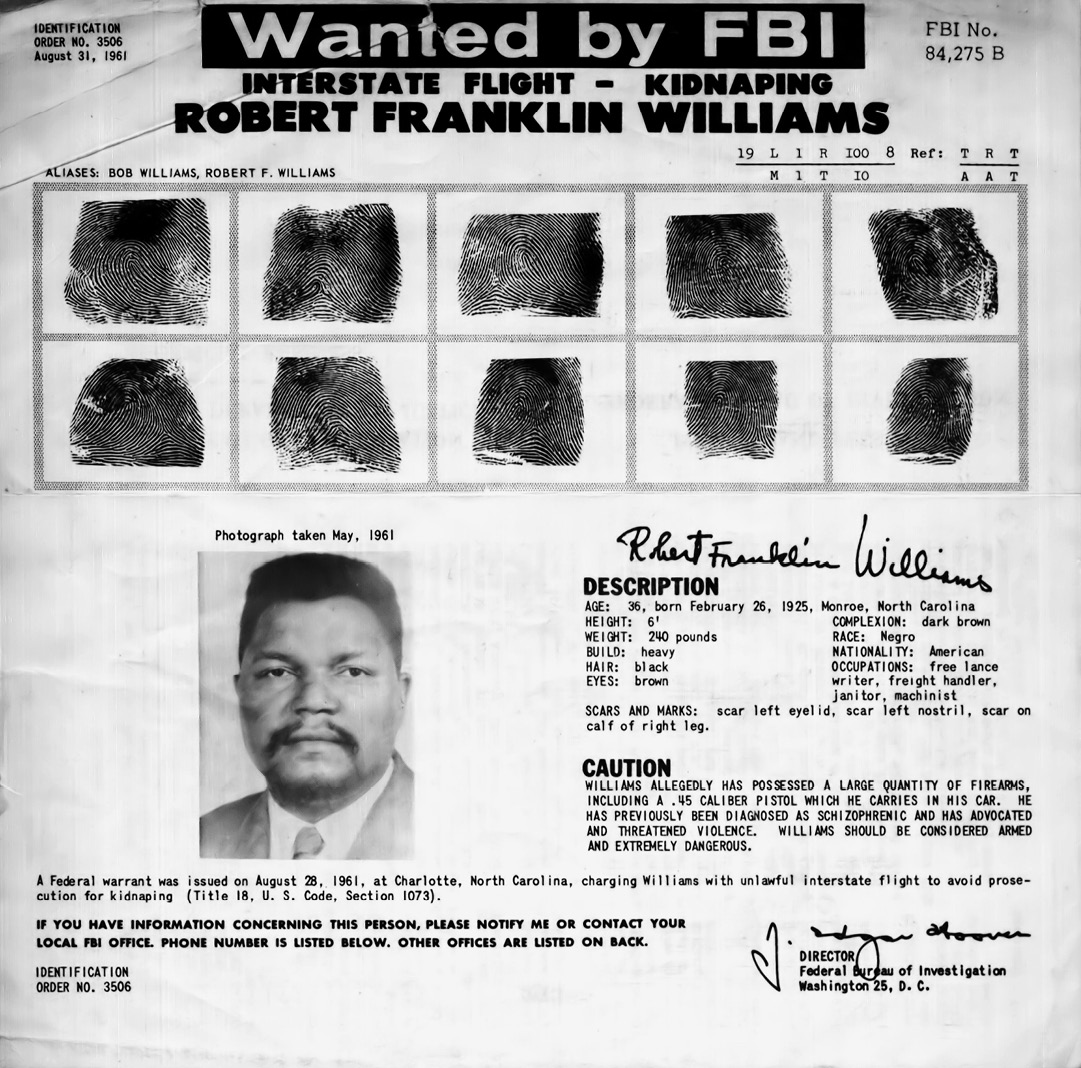

By the time the FBI’s wanted poster was in circulation, Robert F. Williams and family were living in Cuba.

They made their way first to Canada and then, at the invitation of Fidel Castro, went on to Cuba. During four-plus years there, Williams broadcast a radio show to the U.S. called “Radio Free Dixie,” a mix of rock, avant-garde jazz, and commentary on the latest civil rights news. All was well in Cuba for a time, but, as his wife, Mabel, put it, “Rob never stopped being Rob.” At a meeting with the Cuban foreign ministry, he noticed that all the staff were white and said, “It looks like Mississippi in here.” After that, she felt they were lucky to be able to leave. “I thought they would shoot him for sure.”

The Williams family’s next destination was a brief stop in North Vietnam on the way to China, where Mao Tse-tung gave the family a comfortable asylum. Williams was by no means forgotten in the U.S., however. In his absence he was lionized by the leaders and ground troops of the Black Power Movement. But when he finally returned, in 1969, his admirers would be sorely disappointed.

For all the hope of progress the presidency of John F. Kennedy inspired, his administration tried for three years to discourage the activism and so stop the bloodshed of the civil rights movement, to no avail. On May 2, 1963, some 700 school-age children streamed out of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church to demonstrate against segregation. Trained in the principles and techniques of nonviolent resistance, they were beaten, arrested, and imprisoned. The next day, hundreds more took their place. This time Bull Connor turned his police loose on them and stood by watching as they were hit with high-powered fire hoses, beaten with clubs, and set upon by police dogs snarling and straining at their leashes. Hundreds more were arrested that day, but televised coverage, newsreel footage, and especially still images of German shepherds about to sink their teeth into young students, had an effect on the country like no civil rights demonstration had had before. President Kennedy dispatched federal riot control troops to bases near Birmingham and promised to keep the peace, but there was no peace.

Two weeks later, Governor George Wallace made his infamous “stand at the schoolhouse door,” a confrontation with federal troops in which Wallace made a show of trying to stop two Black students from integrating the University of Alabama. Several hours passed as he refused to step aside, but then Kennedy federalized the Alabama National Guard, whose troops dutifully escorted the first two Black students, Vivian Malone Jones and James Hood, into the university.

A few hours later, Kennedy spoke to the nation from the Oval Office and finally placed the full force of his administration behind the cause of civil rights. His speech seemed at times to be almost quoting from Dr. King’s just-published “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” “It ought to be possible,” Kennedy said, “for American students of any color to attend any public institution they select without having to be backed up by troops….

We preach freedom around the world, and we mean it, and we cherish our freedom here at home, but are we to say to the world, and much more importantly, to each other, that this is the land of the free except for the Negroes; that we have no second-class citizens except Negroes; that we have no class or caste system, no ghettoes, no master race except with respect to Negroes?… [T]he time has come for this Nation to fulfill its promise… We cannot say to ten percent of the population… that your children cannot have the chance to develop whatever talents they have; that the only way that they are going to get their rights is to go into the streets and demonstrate. I think we owe them and we owe ourselves a better country than that.

Dr. King was stunned as he watched Kennedy speak. When it was over, he said, “Can you believe that white man not only stepped up to the plate. He hit it over the fence!”

Yet no day’s events went further in proving how inextricably bound together wrong and right could be: Wallace’s stand for white supremacy in the afternoon, Kennedy’s forceful commitment to social justice at 8 p.m., and, just after midnight, the assassination of Medgar Evers.

Evers watched Kennedy’s speech at his office, and after that he had the usual deferred, end-of-day work to finish. People who saw him that night described him, despite Kennedy’s speech, as “very sad and very tired.” He was all but finished with the NAACP, which continued to favor legal challenges over direct action. Even so, he could look back on major accomplishments. He had realized his long-held dream of integrating Ole Miss by helping Air Force Sgt. James Meredith fight the yearslong battle for admission. Whenever Meredith’s resolve faltered, Evers was there with moral support until the night he was killed, three months before Meredith’s graduation. Among the last victories Evers got to see was another, larger boycott of the merchants on Capitol Street in Jackson, which turned students into seasoned activists, who in turn inspired the older generation that had so disappointed Evers before. On the last night of his life, Evers could feel that the Black community of Jackson was more united than it had ever been.

Looking back on that day, Myrlie Evers said her husband seemed to know what was coming. After breakfast he came back into the house twice before he left. “Myrlie, I don’t know what to do,” she remembered him saying. “I’m so tired I can’t go on, but I can’t stop either.”

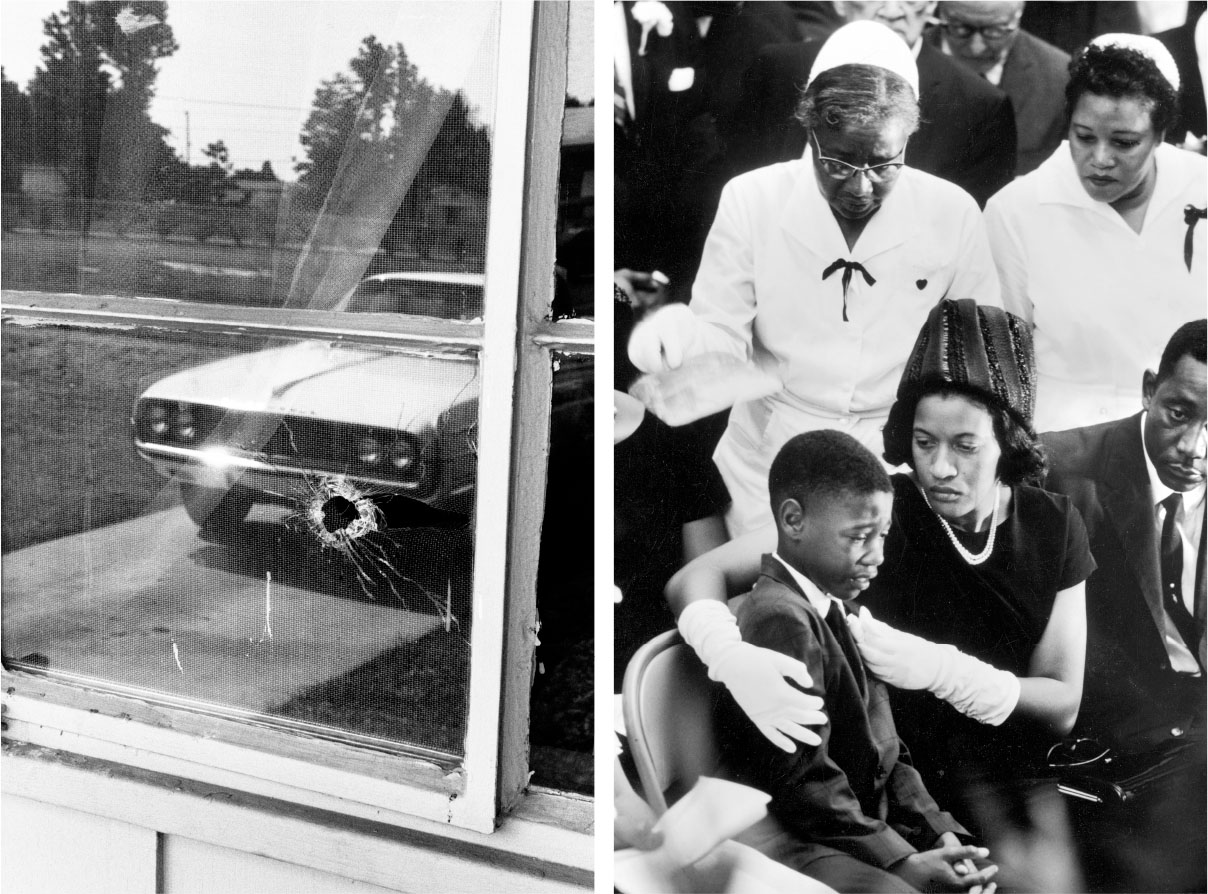

It was just after midnight, four hours after Kennedy’s speech, when he pulled into his driveway, got out of his car, and was killed by a shot in the back from a high-powered rifle. Byron De La Beckwith, who had fired from bushes across the street, was tried twice for the crime, his defense secretly funded by the state of Mississippi, but the all-white juries in both trials failed to reach a verdict. Finally, in 1994, with the same physical evidence but this time presented to eight Black and four white jurors, Beckwith was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. He died in jail seven years later at the age of 80.

Evers’s death at 37 was a seismic event whose aftershocks were felt nationwide. An enormous crowd gathered outside the funeral in Jackson and defied an order of silence when someone started and the rest lifted their voices in “Oh Freedom,” then “This Little Light of Mine.” After the church service, they marched downtown, where they were met by fire trucks, police dogs, and a line of heavily armed police, who charged when someone in the crowd began throwing rocks. The outcome would have been far worse than the arrests and minor injuries that followed if John Doar of the Justice Department had not risked his life by coming between them and shouting at both sides: “My name is John Doar. D-O-A-R. I’m from the Justice Department in Washington. And anybody around here knows that I stand for what’s right!” Then he asked for the crowd to disperse, and for some reason, perhaps his show of courage or the solemnity of the moment, they did. Evers’s body was taken by train to Washington, D.C., where, thanks to his service in World War II, he was buried with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

The volley from a high-powered rifle that killed Medgar Evers in his driveway also hit his car and his home, where his wife and children were waiting up for him. Four days later, at the funeral, Myrlie Evers tried to comfort their son Darrell Kenyatta Evers.

The day Evers was killed was the thirty-sixth birthday of Clyde Kennard, who died three weeks later. To avoid the publicity that would follow if he died in Parchman, Governor Barnett had released him four months before. Free to seek medical care, he flew to Chicago for emergency surgery, but it was too late to slow the advance of his cancer. When the author John Howard Griffin visited him just days before his death, he weighed less than a hundred pounds. During their visit, he kept “a sheet pulled up over his face so no one could see the grimace of pain,” Griffin wrote. Kennard told him that all his suffering would be worth it if his story “would show this country where racism finally leads, but they’re not going to know, are they?” His service would have qualified him for Arlington as well, but he chose to be buried in Hattiesburg.

In late August 1963, the Black veterans of World War II and Korea performed another service to the civil rights movement, providing security for the March on Washington. The Kennedy administration had tried to get the organizers to call it off to prevent the violence that seemed all but inevitable. The veterans knew there would be police in riot gear, and they knew that that sight alone could be an incitement. To ensure the March would not end as feared, the veterans used what they knew. They formed a regiment of three battalions, five companies in each. Company commanders guarded the route, keeping in touch by radio with each other, their headquarters, and the D.C. police; and in a demonstration by some 250,000 people, they kept the peace. The day was, in fact, so peaceful that the Voice of America later broadcast the speeches in a dozen languages, and the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) made a documentary of the event for export.

Not everyone found that coverage useful. SNCC’s Michael Thelwell was sickened when he went by the USIA tent and saw the propaganda in progress. “So it happened,” he wrote later, “that Negro students from the South, some of whom still had unhealed bruises from the electric cattle prods which southern police used to break up demonstrations, were recorded for the screens of the world portraying ‘American Democracy at Work.’ ”

Celebration was indeed too soon, arguably by decades. In the five weeks before and after Evers’s death, according to Martin Luther King’s biographer Taylor Branch, there were 758 racial incidents in 186 American cities, none more moving than the murder of four young Black girls in Birmingham, who were dressed in white for the Sunday service at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church when the bomb went off. But neither the many murders of known and unnamed civil rights advocates nor the Civil Rights Act of 1964 nor the Voting Rights Act of 1965 led to “democracy at work” for Black Americans. Neither would Malcolm X’s assassination and the Watts riots in 1965 nor the founding of the Black Panther Party in 1966, nor all the the many other peaceful and unpeaceful initatives that followed.

After Malcolm X was murdered, Robert F. Williams was the most prominent living standard-bearer for militant activism. He was named in absentia to honorific posts with the Black Panthers and the Revolutionary Action Movement. He was also named president and minister of defense in the Republic of New Afrika (RNA), whose agenda included establishing a Black nation in the Deep South with its own army, funded by reparations for slavery. Williams was nothing if not realistic. His willingness to take on the group’s presidency must have come from a motive apart from commitment to its cause, and speculation about that was the talk of the RNA at the time.

He seemed to be a changed man when he came home in September 1969, and the fact that he was arrested when he got off his chartered plane but immediately released suggests advance negotiations with the U.S. government. He clearly brought useful intelligence with him, having established relations with Mao, Deng Xiaoping, and other leaders of the Chinese Communist Party. In no time, he was being debriefed by the Office of Asian Communist Affairs and by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s briefers on what he had learned in China, including its role and intentions at the height of the Vietnam War. Williams was also given a job teaching in the University of Michigan’s Center for Chinese Studies, a position funded by the Ford Foundation.

Following a press conference two days after Williams got home, a story in the Washington Post noted that Williams had taken “gentle exception to the emotional appeals of some Black nationalists.” Two months later, Williams quietly resigned from one such group, then another. “I had always considered myself an American patriot,” he said at the time. “They didn’t see it that way. I always stressed that I believed in the Constitution of the United States and that I thought it was the greatest document in the world. The problem is that [people] didn’t respect it.”

Later, he was more direct: “They have a lot of young teenagers who might have looked at The Battle of Algiers or something, and they get combat boots and berets, and they grab a gun and go out and say, ‘Off the pigs.’ We had veterans who had been trained to use military equipment…. We always tried to avoid a fight. [They] think a weapon is the first alternative.”

For the next twenty-five years, Robert and Mabel Williams lived in tiny Baldwin, Michigan, a vacation spot tucked into a national forest in the western part of the state. Mabel became a social worker and later project director of a program for seniors. Robert gave some paid speeches at first, then worked with inmates at a nearby prison. Among other things, he urged them to follow the model of Malcolm X, who used his prison years to read and reinvent himself.

Robert’s son Dr. John Chalmers Williams was grateful for his father’s decision to keep a low profile and give to his family the protection he had given to the Black community in Monroe. “The Black leaders our youth know most about—Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Medgar Evers—died young,” Dr. Williams told one interviewer. “The message is like, if you choose to follow these people’s path, this is what happens to you in America. My dad chose to live.”