Tonight was a first for all of us. As each family entered the room and took their seats, there was an undercurrent of tension. No one knew what to expect. Least of all me. Would the parents be inhibited by the presence of their teenagers? Would the kids hold back knowing their parents were watching them? Could I help both generations feel comfortable with each other?

After welcoming everyone, I said, “We’re here tonight to explore ways of talking and listening that can be helpful to all members of the family. Now, that doesn’t sound as if it should be hard, but sometimes it is. Mostly because of the simple fact that no two people in any family are the same. We’re unique individuals. We have different interests, different temperaments, different tastes, and different needs that often collide and conflict with one another. Spend enough time in any home and you’ll hear exchanges like:

‘It’s so hot in here. I’m opening the window.’

‘No! Don’t! I’m freezing!’

‘Turn that music down. It’s too loud!’

‘Loud? I can hardly hear it.’

‘Hurry up! We’re late!’

‘Relax. We’ve got plenty of time.’

“And during the teen years, new differences can develop. Parents want to keep their children safe, protected from all the dangers in the outside world. But teens are curious. They want a chance to explore the outside world.

“Most parents want their teenagers to go along with their ideas about what’s right or wrong. Some teenagers question those ideas and want to go along with what their friends think is right or wrong.

“And if that isn’t enough to fuel family tensions, we also have to deal with the fact that parents these days are busier than ever and under more pressure than ever.”

“You can say that again!” Tony called out.

The teenager sitting next to Tony muttered, “And kids these days are busier than ever and under more pressure than ever.”

There was a chorus of “yeahs” from the other teenagers.

I laughed. “So it’s no mystery,” I continued, “why people in the same family, who love one another, could also irritate, annoy, and occasionally infuriate one another. Now then, what can we do with these negative feelings? Sometimes they come bursting out of us. I’ve heard myself say to my own kids, ‘Why do you always do that?’ … ‘You’ll never learn!’ … ‘What is wrong with you?’ And I’ve heard my kids say to me, ‘That’s stupid!’ … ‘You’re so unfair!’ … ‘Everyone else’s mother lets them’ … “

There were smiles of recognition from both generations.

“Somehow,” I went on, “even as these words are coming out of our mouths, we all know, on some level, that this kind of talk only makes people more angry, more defensive, less able to even consider one another’s point of view.”

“Which is why,” Joan sighed, “we sometimes sit on our feelings and say nothing—just to keep the peace.”

“And sometimes,” I acknowledged, “deciding to ‘say nothing’ is not a bad idea. At the very least, we don’t make matters worse. But fortunately, silence is not our only option. If ever we find ourselves becoming annoyed or angry with anyone in the family, we need to stop, take a breath, and ask ourselves one crucial question: How can I express my honest feelings in a way that will make it possible for the other person to hear me and even consider what I have to say?

“I know what I’m proposing isn’t easy. It means we need to make a conscious decision not to tell anyone what’s wrong with him or her, but to talk only about yourself—what you feel, what you want, what you don’t like, or what you would like.”

I paused here for a moment. The parents had heard me expound on this topic many times before. The kids were hearing it for the first time. A few of them looked at me quizzically.

“I’m going to hand out some simple illustrations,” I said, “which will show you what I mean. To me, they demonstrate the power that both parents and teenagers have to either escalate or deescalate angry feelings. Take a few minutes to look at these examples and tell me what you think.”

Here are the drawings I distributed to the group.

Sometimes Kids Make Parents Angry

When parents are frustrated, they sometimes lash out with angry accusations.

Instead of Accusing … Say What You Feel and/or Say What You’d Like

Teenagers are more likely to hear you when you tell them how you feel, rather than how rude or wrong they are.

Sometimes Parents Make Kids Angry

When teenagers are insulted, they’re sometimes tempted to return the insult.

Instead of Counterattacking … Say What You Feel and/or Say What You’d Like

Parents are more likely to listen when you tell them what you feel, rather than what’s wrong with them.

I watched as people studied the pages. After a few minutes I asked, “What do you think?”

Tony’s son Paul was the first to respond. (Yes, the tall, skinny boy was Tony’s son.) “I guess it’s okay,” he said, “but when I get mad, I don’t think about what I should or shouldn’t say. I just shoot my mouth off.”

“Yeah,” Tony agreed. “He’s like me. Quick on the trigger.”

“I understand,” I said. “It’s very hard to think or speak rationally when you’re feeling angry. There have been times my own teenagers have done things that have made me so furious, I’ve yelled, ‘Right now, I’m so mad, I’m not responsible for what I might say or do! You’d better stay far away from me!’ I figured that gave them some protection and gave me a little time to simmer down.”

“Then what?” Tony asked.

“Then I’d go for a run around the block or take out the vacuum and do all the floors—anything physical, anything that would keep me moving. What helps you cool off when you’re really, really angry?”

There were a few sheepish grins. The kids were the first to respond:

“I shut my door and blast my music.”

“I say curses under my breath.”

“I go for a long bike ride.”

“I bang on my drums.”

“I do push-ups till I drop.”

“I pick a fight with my brother.”

I gestured toward the parents. “And you?”

“I go right to the freezer and finish off a pint of ice cream.”

“I cry.”

“I yell at everyone.”

“I call my husband at work and tell him what happened.”

“I take a couple of aspirin.”

“I write a long, mean letter, and then I tear it up.”

“Now imagine,” I said, “that you’ve already done whatever it is you do to take the edge off your anger and that you’re a little more able to express yourself helpfully. Can you do it? Can you tell the other person what you want, or feel, or need, instead of blaming or accusing them? Of course you can. But it does take some thought, and it does help to get some practice.”

“In the cartoons I just handed you, I used examples from my own home. Now I’d like to ask all of you to try to recall something that goes on in your home that bothers, irritates, or upsets you. As soon as you think of it, please jot it down.”

The group seemed startled by my request. “It can be a big thing or a little thing,” I added. “Either something that has happened or even something that you imagine could happen.”

Parents and kids glanced at each other self-consciously. Someone giggled, and after a few moments everyone started writing.

“Now that you’ve zeroed in on the problem,” I said, “let’s try two different ways of dealing with it. First write down what you could say that you suspect would only make matters worse.” I paused here to give everyone time to write. “And now what you could say that might make it possible for the other person to hear you and consider your point of view.”

The room fell silent as people grappled with the challenge I had set for them. When everyone seemed ready, I said, “Now, will each of you please take your papers and find a parent or a child who is not your own and sit next to him or her.”

After a few minutes of general confusion—amid sounds of shifting chairs and shouts of, “I still need a kid!” and, “Who wants to be my parent?”—people finally settled down with their new partners.

“Now,” I said, “we’re ready for the next step. Please take turns reading your contrasting statements to each other and notice your reactions. Then we’ll talk about it.”

People were tentative about getting started. There was much discussion about who would begin the scene. But once the decision had been made, both parents and teenagers assumed their new roles with conviction. They spoke softly to each other at first and little by little became more animated and louder. A mock fight between Michael and Paul (Tony’s son) drew all eyes in their direction.

“But you always put it off till the last minute!”

“I do not! I told you I’ll do it later.”

“When?”

“After dinner.”

“That’s too late.”

“No, it isn’t.”

“Yes, it is!”

“Just quit hassling me and leave me alone!!”

Suddenly they both stopped, aware that the room was silent and everyone was looking at them.

“I’m trying to get my kid to start his homework earlier,” Michael explained, “but he’s giving me a hard time.”

“That’s because he won’t get off my back,” Paul said. “He doesn’t realize that the more he bugs me to do it, the more I put it off.”

“Okay, I give up,” Michael said, “now let me try the other way.” He took a deep breath and said, “Son, I’ve been thinking … I’ve been pushing you to start your homework early because that’s what feels right to me. But from now on, I’m going to trust you to get started when the time seems right to you. All I ask is that it get done sometime before nine-thirty or ten at the latest, so that you can get a decent night’s sleep.”

Paul flashed a big grin. “Hey, ‘Pop,’ that was much better! I like that.”

“So I did okay,” Michael said proudly.

“Yeah,” Paul replied. “And you’ll see, I’ll do okay too. I’ll do my homework. You won’t have to remind me.”

The group seemed galvanized by the demonstration they had just witnessed. Several teams of parents and kids volunteered to read their contrasting statements aloud. We all leaned forward and listened intently.

Parent (accusing):

“Why do you always have to give me an argument when I ask you to do anything? You never offer to help. All I ever hear from you is, ‘Why me? Why not him? I’m busy.’”

Parent (describing feelings):

“I hate getting into an argument when I ask for help. It would make me so happy to hear, ‘Say no more, Mom. I’m on the job!’ “

Teen (accusing):

“Why didn’t you give me my messages? Jessica and Amy both said they called, and you never told me. Now I missed the game and it’s all your fault!”

Teen (describing feelings):

“Mom, it’s really important to me to get all my messages. I missed out on the game because they changed the day and I didn’t find out until it was too late.”

“All I ever hear from you is ‘Give me…,’ ‘Get me…,’ ‘Take me here,’ ‘Take me there.’ No matter what I do for you, it’s never enough. And do I ever get a thank-you? No!”

Parent (describing feelings):

“I’m happy to help whenever I can. But when I do, I’d like to hear a word of appreciation.”

Teen (accusing):

“Why can’t you be like the other mothers? All my friends can go to the mall by themselves. You treat me like a baby.”

Teen (describing feelings):

“I hate being home on Saturday night when my friends are all having fun at the mall. I feel I’m old enough now to take care of myself.”

Laura, who had been listening with special interest as her own daughter read the last statement, suddenly let out a shriek. “Oh no, Kelly Ann! I don’t care what you say or how you say it, I am not letting a thirteen-year-old go to the mall at night. I’d have to be crazy—with what’s going on in the world today.”

Kelly turned red. “Mom, please,” she entreated.

It took us all a moment to figure out that what had been a practice exercise for the group was a very real and current conflict between Laura and her daughter.

“Am I wrong?” Laura asked me. “Even if she’s with friends, they’re still kids. It’s just plain irresponsible to let young girls go wandering around the mall at night.”

“Ma, nobody wanders,” Kelly retorted heatedly. “We go into stores. Besides, it’s perfectly safe. There are tons of people around all the time.”

“Well,” I said, “we have two very different viewpoints here. Laura, you’re convinced that the mall is no place for an unsupervised thirteen-year-old at night. You foresee too many potential dangers.

“Kelly, to you the mall seems ‘perfectly safe,’ and you feel that you should be allowed to go there with your friends.” I turned to the group. “Are we deadlocked here, or can we think of anything that would satisfy the needs of both Kelly and her mother?”

The group didn’t waste a minute. Both parents and teenagers waded in to solve the problem.

I was impressed by what I had just witnessed. Even more striking to me than the swift resolution of the conflict was the way the group had responded to the standoff between Laura and Kelly. No one took sides. Everyone showed great respect for the strong feelings of both mother and daughter.

“You’ve all just given a clear demonstration,” I said, “of a very civilized way of dealing with our differences. It seems we have to override our natural tendency to prove ourselves right and the other person wrong: ‘You’re wrong about this! And you’re wrong about that!’ Why do you suppose it isn’t just as natural for us to point out what’s right? Why aren’t we just as quick to praise as we are to criticize?”

There was a short pause and then a flurry of responses. First from the parents:

“It’s a lot easier to find fault. That doesn’t take any effort. But to say something nice takes a little thought.”

“That’s true. Like last night my son turned his music way down when he noticed I was on the phone. I appreciated his doing that, but I never bothered to thank him for being so considerate.”

“I don’t know why kids have to be praised for doing what they’re supposed to do. Nobody praises me for getting dinner on the table every night.”

“My father thought praise was bad for kids. He never complimented me because he didn’t want me to get a ‘swelled head.’ “

“My mother went to the other extreme. She never stopped telling me how great I was: ‘You’re so pretty, so smart, so talented.’ I didn’t get a swelled head, because I didn’t believe her.”

Teenagers joined the discussion:

“Yeah, but even if a kid did believe her parents and thought she was so special, when she goes to school and sees what other kids are like, she could be in for a big letdown.”

“I think parents and teachers, they say stuff like, ‘Terrific,’ or ‘Great job,’ because they think they’re supposed to. You know, to encourage you. But me and my friends, we think it sounds phony.”

“And sometimes grown-ups praise you to get you to do what they want you to do. You should’ve heard my grandmother the time I got this really short haircut. ‘Jeremy, I hardly recognized you. You look so handsome! You should keep your hair that way all the time. You look like a movie star!’ Yeah, right.”

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with a compliment if it’s sincere. I know I feel great when I get one.”

“Me too! I like it when my parents say something nice about me to my face. Actually, I think most kids can use a little praise—now and then.”

“I have news for you kids,” Tony said. “Most parents can use a little praise—now and then.”

There was a burst of applause from the parents.

“Well,” I said, “you’ve certainly expressed a wide range of feelings about praise. Some of you like it and wouldn’t mind hearing a lot more of it. And yet for some of you it’s uncomfortable. You experience praise as either insincere or manipulative.

“Could the difference in your responses have something to do with how you’re being praised? I believe it does. Words like, ‘You’re the greatest … the best … so honest … smart … generous …’ can make us uneasy. Suddenly we remember the times we weren’t so great or honest or smart or generous.

“What can we do instead? We can describe. We can describe what we see or what we feel. We can describe a person’s effort, or we can describe his achievement. The more specific we can be, the better.

“Can you hear the difference between ‘You’re so smart!’ and ‘You’ve been working on that algebra problem for a long time, but you didn’t stop or give up until you got the answer’?”

“Yeah, sure,” Paul called out. “The second thing you said is definitely better.”

“What makes it better?” I asked.

“Because if you tell me I’m so smart, I think, I wish, or, She’s trying to butter me up. But the second way, I think, Hey, I guess I am smart! I know how to hang in there until I get the answer.”

“That does seem to be the way it works,” I said. “When someone describes what we’ve done or are trying to do, we usually gain a deeper appreciation of ourselves.

“In the cartoons I’m handing out now, you’ll see examples of parents and teenagers being praised—first with evaluation, then with description. Please notice the difference in what people say to themselves in response to each approach.”

When Praising Kids

Instead of Evaluating …

Describe What You Feel

Different kinds of praise can lead kids to very different conclusions about themselves.

When Praising Kids

Instead of Evaluating …

Describe What You See

Evaluations can make kids uneasy. But an appreciative description of their efforts or accomplishments is always welcome.

When Praising Parents

Instead of Evaluating …

Describe What You Feel

People tend to push away praise that evaluates them. An honest, enthusiastic description is easier to accept.

When Praising Parents

Instead of Evaluating …

Describe What You See

Words that describe often lead people to a greater appreciation of their strengths.

I noticed Michael nodding his head as he looked over the illustrations.

“What are you thinking, Michael?” I asked.

“I’m thinking that before tonight I would’ve said that any kind of praise was better than none. I’m a big believer in people giving each other a pat on the back. But I’m beginning to see there are different ways to go about it.”

“And better ways!” Karen announced, holding up her cartoons. “Now I understand why my kids get so irritated when I tell them they’re ‘terrific’ or ‘fantastic.’ It drives them crazy. Okay, so now I’ve got to remember—describe, describe!!”

“Yeah,” Paul called out from the back of the room. “Cut out the gushy stuff and say what you like about the person.”

I seized upon Paul’s comment. “Suppose we all do exactly that—right now,” I said. “Please return to your real family. Then take a moment to think about one specific thing that you like about your parent or teenager. As soon as it comes to mind, put it in writing. What could you actually say to let the other person know what it is that you admire or appreciate?”

There was a wave of nervous laughter. Parents and kids looked at each other, looked away, and then down at their papers. When everyone had finished writing, I asked them to exchange papers.

I watched quietly as smiles grew, eyes filled, and people hugged. It was sweet to see. I overheard, “I didn’t think you noticed”…“Thank you. That makes me really happy”…“I’m glad that helped”…“I love you too.”

The custodian poked his head in the door. “Soon,” I mouthed to him. To the group I said, “Dear people, we have come to the end of our final session. Tonight we looked at how we can express our irritation to each other in ways that are helpful rather than hurtful. And we also looked at ways to express our appreciation so that each person in the family can feel visible and valued.

“Speaking of appreciation, I want you to know what an enormous pleasure it’s been for me to work with all of you over these many weeks. Your comments, your insights, your suggestions, your willingness to explore new ideas and take a chance with them have made this a very gratifying experience for me.”

Everyone applauded. I thought people would leave after that. They didn’t. They hung around, talked to one another, and then each family lined up to say good-bye to me personally. They wanted me to know that the evening had been important to them. Meaningful. The kids as well as the parents shook my hand and thanked me.

When everyone had gone, I stood lost in thought. Almost everything in the media these days gives a picture of parents and teenagers as adversaries. Yet here tonight I had witnessed a very different dynamic. Parents and teens in partnership. Both generations learning and using skills. Both generations welcoming the opportunity to talk together. Happy to connect with each other.

The door opened. “Oh, we’re so glad you didn’t leave yet!” It was Laura and Karen. “Do you think we could have one more meeting next Wednesday—just for parents?”

I hesitated. I hadn’t planned to go on.

“Because we were all talking in the parking lot about the stuff going on with our kids that we didn’t think we should bring up tonight with them sitting there.”

“And you wouldn’t have to worry about contacting people. We’d take care of that.”

“We know it’s last-minute, and some people said they couldn’t make it, but it’s really important.”

“So would that be okay with you? We know how busy you are, but if you have the time …”

I looked into their anxious faces and mentally rearranged my schedule.

“I’ll make the time,” I said.

a quick reminder

TO YOUR TEENAGER

Instead of accusing or name-calling:

“Who’s the birdbrain who left the house and forgot to lock the door?!!”

Say what you feel: “It upsets me to think that anyone could have walked into our home while we were away.”

Say what you’d like and/or expect: “I expect the last person who leaves the house to make sure the door is locked.”

TO YOUR PARENT

Instead of blaming or accusing:

“Why do you always yell at me in front of my friends? No one else has parents who do that!”

Say what you feel: “I don’t like being yelled at in front of my friends. It’s embarrassing.”

Say what you’d like and/or expect: “If I’m doing something that bothers you, just say, ‘I need to talk to you for a second,’ and tell me privately.”

TO YOUR TEENAGER

Instead of evaluating her:

“You’re always so responsible!”

Describe what she did: “Even though you were under a lot of pressure at your rehearsal, you made it your business to call when you knew you were going to be late.”

Describe what you feel: “That phone call saved me a lot of worry. Thank you!”

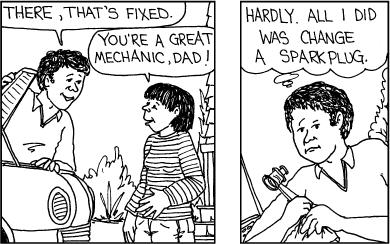

TO YOUR PARENT

Instead of evaluating him:

“Good job, Dad.”

Describe what he did: “Boy, you spent half your Saturday setting up that basketball hoop for me.”

Describe what you feel: “I really appreciate that.”