8Kiso Fukushima and Mount Ontake

Mountains on top of mountains.

This is ken [keeping still], and means to stop.

When it is time to stop, [the Gentleman] stops;

when it is time to go, [the Gentleman] goes.

Thus, motion and peace do not lose their moments.

That is the bright and clear way . . .

Therefore, the Gentleman does not let his thoughts

go beyond his situation.

—I-Ching, hexagram 54

KISO FUKUSHIMA: Elevation 2,370 Feet

Kiso Fukushima was and remains today the largest of the eleven post towns on the Kiso Road, not only because of the imposing barrier here, but also due to its lively commerce. Kaibara Ekiken noted that “all sorts of things are sold here,” and Okada Zenkuro reported the following:

This post town has the most commerce and products for sale in the entire Kiso Valley. The leaders of the community are wealthy. . . . Every year there is a horse market where various kinds of cotton and hemp goods, wooden tools and implements, preserved mochi, black pepper, dried bracken, rock mushrooms, and salted fish from both the southern and northern seas are sold. It is a prosperous and bustling town. Thus, even people of lower ranks carry on with their livelihoods in a good fashion.

I hobbled past the barrier, situated on the highest point of the northern end of the town, and slowly made my way down the hill into the town proper. The main road, which now joins, now separates from the old Nakasendo threads through a lively area of dry-goods shops, banks, bars, a high-end sake shop, two food markets, and a minipark where travelers can soak their feet in a three-foot-by-six-foot hot spring bordered by cedar planks while the Kiso River rushes by far on the right. Several bridges cross the river to the west side of town, but eventually, as the town thins out, the river broadens and flows rapidly along only a few feet from the road.

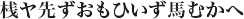

A little farther along was my inn, its entrance facing the road, its westernmost rooms right on the river itself. The Sarashina-ya had originally been established in 1872 near the barrier but was torn down and rebuilt at its present location in 1927. It is difficult to tell whether it is a two- or three-story building because of the curious way the stairways wind up and down, but all of the rooms—which are of various sizes—are traditional, with tatami floors and wooden beams. There is at least one scroll of either Japanese scenery or calligraphy on the wall in even the smallest of the rooms, which are generally for two guests. Other rooms will accommodate six to eight people. Mr. Ando, whose ancestors were samurai retainers to the local lord, is the sixth-generation owner of the inn, but his wife, Mineko, actually runs the place with a quiet but very efficient hand. Printed next to her name on her business card is

, pronounced o-kami, literally meaning “lady general.”

, pronounced o-kami, literally meaning “lady general.”

Mineko, a tall, handsome woman in her mid-fifties, greeted me at the entranceway with a warm but half-distracted smile. “Gomen nasai, Biru-san,” she apologized. “We have a full house—twenty construction workers from Nagoya—so I can’t put you in your favorite room over the river. I hope you don’t mind.” The room she referred to is a large one, enough for four people, overlooking the Kiso River. I once stayed there during a typhoon and watched the waves roil and leap over the boulders midstream, wondering if we weren’t all going to take a ride down to the next post town that night. At other times, it has simply been a swiftly flowing current, clear enough to see the bottom and for birds to play along the banks. On the wall of this room hangs a scroll of calligraphy from some Buddhist scripture, and over the door are amulets from Mount Ontake. With the window open at night, sleep comes to the voice of the river, soothing any aches and pains acquired during the day. It is my favorite room on the entire Kiso Road.

But this time I was led up to a small but comfortable room overlooking the road—a road, I reminded myself, people have walked for over a thousand years. Cars, for the most part, have taken the place of straw-sandaled feet, but there are still many of us who take this route on foot.

Soon, Mineko and her daughter appeared at my door with coffee and mikan, small Japanese tangerines, and we talked about the plans I had for climbing Mount Ontake. Her husband had arranged for a young artist, Yamashita Katsuhiko, who is also a mountaineer and a practitioner of the Ontake religion, to accompany me, but she had noticed my limp and wondered if I was in any condition for the climb. In her mother-general sort of way, she asked me to take off my socks for a look at my feet, and when I did, we all looked aghast at the sight: large red blisters on top of blisters, both right and left, and for the first time I understood the meaning of the word in Japanese—mame (meaning “bean”). Mineko gave me her most serious look, declared the climb to be off, and said that she would call Mr. Yamashita to let him know. I did not struggle with this decision, which had been creeping up on me for a couple of days.

When it is time to stop, the Gentleman stops;

When it is time to go, the Gentleman goes . . .

and does not let his thoughts go beyond his situation.

This done, we chatted for a while longer, coffee was refilled, and Mineko and her daughter—who had recently graduated from college and had come back to help with the inn—made polite apologies for taking up too much of my time (“Nagajiri itashimashita”—literally, “We have made long buttocks.”) and took their leave. Lunch is generally not served in Japanese inns, so I followed them down, gingerly put my boots back on, and slipped out the entranceway.

It is a short walk along the river back into town and into my favorite coffee shop there, the Jyurin. The proprietress greeted me with a “Welcome back!” and showed me to a seat at a wooden table overlooking the river. This is a small establishment, only five tables with seating for twenty at the most, and is perfectly situated for whiling away an afternoon. The west wall is mostly a sliding glass window, and just beyond the road across the river, the mountain angles up, allowing only a narrow view of the sky. Today, yellow leaves—ginkgo, maybe?—were falling into the clear current and being swept downstream over the blue-gray rocks beneath. A small black-and-white bird, the sekirei (a kind of wagtail), flitted quickly and nimbly over the rushing water and exposed boulders. Watching the yellow leaves flow away, I was aware of the maudlin thought of just how many years had gone by, just as fast, disappearing from sight.

The proprietress brought me a bowl of rice topped with shrimp tempura, and a cup of tea, and I quickly had other more immediate things on my mind. Opening my wooden chopsticks and mumbling, “Itadakimasu” (“I humbly receive”), I got to work.

Back at the Sarashina-ya, there was time for a bath. Again, it was early and the other guests were still out, so I could take my time, first washing off, seated on one of the low wooden stools, and then dipping into the one-man wooden tub. It would be easy to fall asleep here, and some people do, although it is not recommended. After thirty minutes, I roused myself, dried off, and got back upstairs for a long nap. Outside, the sky had begun to scud over with clouds, and the temperature had dropped. I turned on my gas heater and drifted away, one more leaf down the stream.

At six thirty, I awoke to Mineko calling me down for dinner. The Sarashina-ya has been a minshuku since it was rebuilt here nearly ninety years ago, so the guests all eat in a large tatami-floored room on the first floor. Cushions are placed around low wooden tables, seating is indicated by room numbers, and the usual numerous dishes are set out ahead of time. Beer and sake are available from a large upright glass cooler at the end of the room. The construction workers filed in and took their places, tired from a day of work. These were tough-looking men but polite and deferential to the lady-general, and I noticed that one of them was wearing a Hello Kitty sweatshirt and sweatpants. “Cute” here in Japan seems to know no social or gender boundaries.

We all eagerly worked through our dishes of fish, vegetables, rice, miso soup, soba, pickles, and tangerines, watched the news on the TV at the other end of the room, and, one by one, returned to our rooms to end the day. I noticed that a number of my inn mates were bringing large bottles of sake up to their rooms with them, but my one bottle of Asahi Draft with dinner would suffice for the night.

Back under the futon, I selected one of the books on local tales from the bookstore in Harano. It includes a short story about a fox at the Kozenji, the most famous temple in Kiso Fukushima.

In a hamlet just in front of the gate to Kiso Fukushima, there is a temple called the Kozenji. There is a beautiful garden in this temple, and, just inside the garden grounds, there stands a mortuary marker for a fox.

At the beginning of the Meiji period, a fox had shape-shifted into a human being and was serving as a young acolyte at the temple. The abbot was aware that this was really a fox but allowed him to stay in the temple anyway. Thus, when the little acolyte was taking a nap and carelessly let his tail into view, the abbot would lean down and whisper, “Hey, hey. Your tail is showing.”

One day, the abbot sent the little acolyte off with a message to someone in the hamlet of Hiwada. The fox/boy successfully delivered the message to its destination, but on the return road, he was shot with a rifle and killed. When seen with the naked eye, the acolyte had appeared just like a human being, but when sighted down the barrel of a gun, it could be seen that he was nothing but a fox. Because of this, the hunter had taken aim and fired.

The priest waited anxiously for the acolyte and finally became so concerned that he walked to Hiwada himself. On the mountain road, he found the body of the acolyte and carried it back to the temple. There, out of grief, he buried its bones and set up a mortuary marker.

This is said to be the story of the mortuary marker of the fox.

At midnight, I was awakened by Jon Braeley, a friend and independent filmmaker from Miami. He had just come in on the last train from Tokyo with two large suitcases full of camera equipment. I was in such a daze—my head full of foxes, priests, and temple gardens—that I could only welcome him in with a wave from the futon and indicate the closet where his own bedding was stored. I quickly returned back to intermittent sleep until dawn.

BREAKFAST CALL came all too early, and we headed downstairs for a surprise: a Western-style breakfast of eggs, sausage, and toast. Mineko had been thoughtful enough to prepare something more suited, she thought, than the usual fare for her two American guests, and I, for one, enjoyed the change. The Japanese version of toast is always cut about an inch and a half thick and is liberally coated with melting butter. I dug in.

Jon and I talked over the day with several cups of coffee—also there for our exclusive enjoyment. He had just arrived in Japan and had come to film the Japanese National Kendo Tournament but thought it might be interesting to first see some of the area I had recommended to him over the years. His schedule was tight, so we would just have time to look over this little country town before he headed back to Tokyo, one of the largest and most modern cities in the world. Jon is originally from England and is cheerful and talkative—an excellent companion after a number of solo days on the road. The old Japanese saying puts it very simply:

For journeys, a companion.

Travel is touted as expanding one’s experiences and outlook about the world, but I often fear that in walking alone for too long, my perceptions tend to feed upon themselves and to be satisfied with my own provincial habits and insularity. There is certainly no joy equal to walking through these mountains alone, but I can hardly count the number of times I’ve had my eyes opened by a casual remark dropped by a fellow traveler. On the other hand, hard experience has shown that you must pick your companions well. In his essay On Going on a Journey (1822), William Hazlitt wrote about the unfortunate effects of having the wrong traveling companion during significant moments on one’s journey:

These eventful moments in our lives’ history are too precious, too full of solid, heartfelt happiness to be frittered and dribbled away in imperfect sympathy. I would have them all to myself, and drain them to the last drop.

Jon, however, is a filmmaker and, aside from being good-natured and intelligent, has an eye open constantly for what is around him.

The temperature had dropped into the upper forties or lower fifties Fahrenheit, not uncommon for late October in the Kiso Valley, and it was going to be a cold and long walk carrying heavy camera equipment, when we were given another surprise. The preparation and serving of breakfast in the inn being over, Mineko had decided to leave operations to her daughter and suggested (lady-general-like) that we allow her to drive us through town and up the hill to the Fukushima sekisho, or barrier. The car was already out in front, she said, so please get in. There was clearly no room for us to argue, even if we had wanted to, and soon, her little car was winding up a very narrow road, bypassing the many stone steps up the 250-foot steep slope atop which the barrier sits. The open wooden building and gates occupy a flat stretch of ground no more than 220 feet long; to the east is the edge of Mount Seki, while to the west, the cliff cascades down to the Kiso River. This was not an easy place to get through unnoticed.

As Jon set up his camera equipment, Mineko, a part-time tour guide, explained that Kiso Fukushima, being just about at the center of the Kiso Valley and midway between Edo and Kyoto, occupied a strategic and essential site in the line of traffic. Thus, it was an extremely appropriate place for establishing a barrier. No one knows when the original barrier was built, but the Nakasendo was “opened” in 1601, so it was probably not long after that. During the period of the Kiso clan domination of the area, smaller barriers had been erected at Niekawa and Tsumago, and likely here, too; but when control of the valley passed into the hands of the Tokugawa, the buildings and gates were strengthened and put under the management of the Yamamura clan, who became the hereditary magistrates.

The length of the barrier runs north-south and hugs the western side of the mountain. Travelers, from warlords and their retinues to commoners, had to wait their turn to go before the official and receive permission to pass through, and at any other season than summer, the delay must have involved much shivering and stamping of feet against the cold. The sun had not yet peeked over the crest of the mountain, and it was more than just a little chilly this mid-autumn morning, so Mineko and I walked inside the unheated edifice, more just to keep moving than from any warmth it might provide.

The structure at this barrier is much like that at Niekawa, only larger and more imposing. We took off our shoes at the open entranceway, a display of various weapons used during Edo times at our left. These include spears, bows, staves, and a curious one with a long wooden handle and two-foot curled barbs at one end. This was for stopping people trying to run through the barrier by snagging their clothes rather than for inflicting any real harm. How people might have thought that they could get by soldiers armed with such weapons waiting at either end of the narrow pathway is not clear.

Inside the otherwise bare room are displays of the wooden passes issued to go through the barrier, documents, old illustrations, and firearms from the period. Originally, this had been an area for guards or servants to rest or simply to wait when they were on call. The next and largest room is open to, and about three feet above, a courtyard of small stones—sand when the barrier was in use—in which is a brazier, a flat cushion, a small desk, and an armrest for the official conducting the inspection of papers and passes. Travelers other than warlords, their retinues, and aristocrats would kneel in the sand awaiting the go-ahead from the official. The room on the farthest end is the small dark room where “boys” would be inspected by an old lady with a large magnifying glass if their sex was in question. There are other very small rooms for things such as delivering tea to the official and his assistants, and a short hallway to the rear of these. Two large wooden gates, north and south, allowed travelers to enter and exit.

On a busy day, the official’s tedium would only have been broken by the interesting variety of travelers who were applying to pass through: warlords, ronin, farmers on pilgrimages, traveling musicians, poets and actors, businessmen and their assistants, and people of all types just traveling because they could. The Kiso is known for having a culture with elements of both eastern and western Japan, and as the men and women of different classes were forced to wait together in the inns in post towns like Fukushima and Narai, there must have been interesting exchanges of ideas, styles, songs, stories, and even jokes, as travelers and their hosts got a taste of faraway places they would never themselves have passed through. Originally intended to discourage movement, barriers like the one here did more to encourage a flow of ideas and perhaps even a fuller sense of what it was to be Japanese.

Sunlight had started to appear across the river on the crests of Mount Seki, and Jon had finished with a series of photographs of the area, so we began to pack up. As we put Jon’s heavy equipment into the tiny trunk of Mineko’s car, she explained that this barrier was in operation until February of 1869 and demolished later in an attempt to rid the country of all vestiges of Tokugawa power and influence. The site of the barrier, however, had been excavated in 1975, and its remaining structure and full placement of buildings and design all confirmed by comparing documentary materials. Reconstructed in 1977, it was designated as a national historical site two years later. As we began to leave, Japanese tourists were beginning to climb up the long stone steps (punctuated every ten yards or so by a statue of the bodhisattva Jizo, the protector of travelers) to get a feeling for their own national history—but, no doubt, without the sense of anticipation that their Edo-period ancestors would have felt.

MINEKO’S NEXT STOP was the site of the mansion of the hereditary magistrates of Kiso Fukushima, the barrier, and much of the Kiso Valley in general—the Yamamura clan. The Yamamura were once the vassals of the Kiso clan, but they had fought bravely at Sekigahara and were consequently ordered to their elevated position by Tokugawa Ieyasu.

We crossed the Otebashi Bridge—the oldest concrete bridge in Japan—and parked in front of the old stone walls that once delineated part of Kiso Castle but now mark what is left of the lower mansion and garden. With the maps extant today, we can imagine the extensive size of the magistrate’s palatial mansion during the Edo period—only one-tenth of which remains today. In his travelogue of the Kiso, Kisoji kiko, the haiku poet Yokoi Yayu wrote under the year 1745,

In Fukushima today—the 12th—I was allowed to visit the Yamamura clan’s mansion. It was spotlessly clean, and the servants ran around with both upper and lower formal garments, asking what we would like. Spreading out trays of sea bream and yellowtail, it did not feel like a mountain home at all.

On the day of chopping blocks,

not a trace

of the cuckoo.

The cuckoo is a bird that seeks out solitary places and only sings when it has the leisure to do so.

Mineko, Jon, and I took off our shoes and walked through the preserved remains of the lower mansion, which was reconstructed in 1723 by the thirteenth-generation magistrate. The halls are filled with the costumes, armor, and art of the Edo period, several of the Yamamura having been scholars and artists of some note, and this section of the mansion had had an extensive library as its center. Turning through the hallway, we came upon displays of the meals that were offered to visiting dignitaries, including the fortunate Yokoi Yayu: every seafood imaginable—brought in fresh from both the Pacific and the Sea of Japan—river fish, mountain vegetables, and herbs served on red and black lacquerware trays, plates, and dishes attest to the wealth and prestige of the clan.

According to a map of the mansion dated 1823, there were some twenty-three gardens, and among those, there were five with miniature lakes. To the right, however, through the sliding glass doors, the only remaining garden opens up to the east. Although the leaves on the trees were gone at this time, making it look some-what forlorn, the garden has a small pond and uses the technique of shakkei, or “borrowing scenery,” with Mount Komagatake far in the distance. A waterfall falls in cascades into some rapids and then enters the pond, which is surrounded by a number of “guardian rocks.” A stone bridge crosses the pond to an island, where a “snow-viewing lantern” has been set. On a small stylized mountain to the left of the waterfall is a Fudo Myo-o stone, which guards the source of the water and watches over it as it passes. This stone also manifests lucky events for the household, which it did well for over two hundred fifty years, and protects the house itself. Behind the waterfall there is a shrine to Inari, and an old lantern is engraved with the date 1782.

The Yamamura seemed to have held Inari, the god of the harvest, in high regard, and one of the last displays to be seen as you walk through the mansion is that of a preserved two-hundred-year-old carcass of a fox—Inari’s messenger—enshrined in a small room of its own. As Okada Zenkuro pointed out in a number of places in his report, the Kiso Valley experiences cold temperatures, is surrounded by mountains, and has few level places for agriculture. Thus, the harvest god and her messengers were held in great esteem, and, no doubt, fried tofu—one of the foxes’ favorite dishes—was often set out in places where the furry animals were known to pass by.

Before we piled back into Mineko’s car, she pointed out the stone on the old fortifications on which the above haiku by Yayu was engraved. As I posed with Mineko for the de rigueur commemorative photograph, I couldn’t help thinking of the poet’s lucky day at this once-huge mansion. Yayu was a man of the samurai class, had founded a school of military science, and was a senior bureaucrat in charge of the castles at Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto. But the cultured Yamamura were likely most pleased to have him there in his capacity as a famous writer of haiku and later recited his commemorative poem with satisfaction and pride.

Another poem, with an introduction, by Yayu shows his more sensitive side and may indicate the direction of the conversation that day:

At the hottest time of the year, it was difficult to bear, and I hummed verses to myself about the cicadas and the heat. But the days passed by, and soon their voices grew weaker in the autumn wind, and I began to feel sorry for them.

May at least one of them

remain alive:

autumn cicadas.

We cannot say that people are really living if they are not also living within nature, that is, living within the garden. Gardens play an important role in our health, just as in olden times there was the saying, “In houses where gardeners come and go, there is no need for the doctor.” The garden is essential to our life, and not something we can do without.

—Mirei Shigemori, Modernizing the Japanese Garden

Our last stop for the morning was the Kozenji, one of the five temples in Kiso Fukushima and one of the three most famous in the Kiso Valley. Well known as the family temple for both the Kiso and Yamamura clans, it was built in 1434 by Kiso Nobumichi for the Buddhist memorial services for his ancestors, although the temple itself must predate this by centuries. Now under the Zen Buddhist order, it was likely first established as a Tendai or Shingon temple in the eleventh century, for in front of the main hall is a weeping cherry tree said to have been planted as a seedling by Yoshinaka himself. Mineko, Jon, and I slowly walked up the graded approach to the temple, passing by a huge flat rock, supposedly for practicing Zen meditation. On our left was a large statue of Jizo comforting two children and, farther up the walkway, six smaller statues of Jizo, one for each of the six realms through which we transmigrate.

Mr. Ando’s ancestors are also memorialized here, so Mineko passed through the gate separating the walkway from the temple, spoke quickly with the attendant priest, and on her return, informed us that there would be no entry fee.

On our way through the gate, a young priest with shaven head and informal beige baggy pants and upper garment stood in the entrance to the main temple on our right. He greeted us with a silent nod and withdrew into the dark interior.

Facing the main entrance to the temple is the expansive “dry garden” created by the garden master Shigemori Mirei in 1963, called the Kan’untei  , “Garden for Observing the Clouds.” Extending out from the front of the main hall, the garden contains a large flat area of small pebbles, broken up by three groups of fifteen rocks of various sizes. The pebbles are raked in broad curving patterns out into the four directions, suggesting a sea of clouds, while the dark rocks appear to be the peaks of mountains rising above those clouds. These “peaks” are arranged in asymmetrical groups of seven, five, and three—shichigosan in Japanese—the three ages considered critical for children and the ages when they are taken to a shrine on November 15 to ask for the gods’ protection. The entire effect is one of movement and change within empty, still space. The garden itself is enclosed by a white wall topped with dark tiles and, beyond that, a few large trees now with red and orange leaves. Even farther beyond are the mountains rising from the other side of the post town. Concerning his gardens, Mirei wrote,

, “Garden for Observing the Clouds.” Extending out from the front of the main hall, the garden contains a large flat area of small pebbles, broken up by three groups of fifteen rocks of various sizes. The pebbles are raked in broad curving patterns out into the four directions, suggesting a sea of clouds, while the dark rocks appear to be the peaks of mountains rising above those clouds. These “peaks” are arranged in asymmetrical groups of seven, five, and three—shichigosan in Japanese—the three ages considered critical for children and the ages when they are taken to a shrine on November 15 to ask for the gods’ protection. The entire effect is one of movement and change within empty, still space. The garden itself is enclosed by a white wall topped with dark tiles and, beyond that, a few large trees now with red and orange leaves. Even farther beyond are the mountains rising from the other side of the post town. Concerning his gardens, Mirei wrote,

If what the gods made is nature, then the garden is the part that the gods forgot to make. So it is up to us to take the place of the gods and make gardens. We ourselves must become gods.

Mirei was a native of Okayama Prefecture who studied tea ceremony and flower arranging in his teens. In college he studied Japanese painting, art history, and philosophy, courses and interests that would eventually lead him to a life of creating gardens. Almost all of his gardens—which grace shrines, temples, castles, and even a town hall—are in the style of karesansui, or “dry landscape,” Zen influenced but at the same time quite modern. On this cloudless day, the contrasts between the apparent movement of the white pebbles and the primordial stability of the dark rocks are astonishing. Confucius wrote,

When the foundation is established, intelligent movement is born.

Mountains and the flowing clouds: stability and movement. I tried to imagine how Mirei first conceived of this remarkable creation but brushed the thought aside. That is not the point here. The very name of the Kan’untei is instructive of how it should be viewed, after all: the first character  , kan, depicting a hand held over the eyes, like a person looking into the broad distance, not into a scramble of thoughts.

, kan, depicting a hand held over the eyes, like a person looking into the broad distance, not into a scramble of thoughts.

Jon and Mineko had finished up trying to take photographs of the garden. “I have lived here for so many years,” she exclaimed with mild exasperation, “but still can’t get it right.” Jon just screwed up his face with a funny smile as if to ask, “How do you get something like this?”

Before we left, we found the entrance to the much smaller Edo-period garden to the south and rear of the main temple. Compared to the Kan’untei, this garden is cramped and crowded with moss, bushes, trees, and even a tiny stream or pond—hard to tell which—with a stone slab bridge. The vegetation is meticulously cared for here—each bush and tree kept at a certain shape and size—and while the garden is clearly a harmonious whole, attention can be paid to each element that creates that whole. The eye moves from tree to bush, some red with autumn, others evergreen, but with composure rather than in haste. After a short quiet moment, we moved on.

IT HAD BEEN a long morning, and Mineko was expected back at the inn to begin preparations for the evening meal. With apologies, she dropped Jon and me off in the old part of the post town, an interesting area with winding narrow streets and wooden houses of traditional architecture. We passed by a fountain made of two wooden pipes emptying water into a wooden basin, which a faded sign declared it had been doing continuously for the last five hundred years. Around the corner was the site of the old signboard that advised travelers of what they needed to know about the town. The street—this was the old Kiso Road again—wound down the hill through lacquerware shops that have been in business since the Edo period and then past the city hall, the site of the old honjin. In the rear garden behind the city hall stands a stone slab engraved with a haiku from Basho.

Skinny crab

legs crawling

out of the pure water.

This monument once stood upright in the middle of a vegetable field where clear water bubbled up from the ground, but it was moved to its present site in 1953. When or why it was originally placed in the vegetable field is unknown.

In this part of town, or near it, is the site of the old castle built by Kiso Yoshiari. It was a typical Warring States–period fortification with a moat, winding streets, and a reservoir but was burned to the ground, and the site is now occupied by Kiso Fukushima Elementary School. Looking up this locale lost out to hunger, however, so the two of us made our way back to the coffee shop for lunch, watched the leaves carried by the river go by, and then headed home. Jon had editing work to do, and I was ready for another long, hot bath and a nap. On the way to the inn, I could not pass up buying some tasty Japanese tangerines, then in season, at a local grocery store. Mikan are sweet, the peel is loose and easy to remove, and we managed to finish the entire bag off soon after settling in to our room.

With early evening, we were called down to dinner with the construction workers, and Jon generously ordered a large bottle of sake, which went well with the grilled river fish, the thick, sweet miso sauce on steamed eggplant, rice, a variety of vegetables, and miso soup. Back up in our room, he ordered yet another bottle, and we finished off the evening exchanging stories of living and traveling in Japan, Miami, and elsewhere in the world. I was greatly entertained with his accounts of the recent Halloween being enthusiastically celebrated in bars and nightclubs in Tokyo and how young ladies there dressed as Raggedy Ann, Cinderella, and French waitresses, while the men wore costumes of pirates and Pokemon. We had started the day with the ancient traditional barrier and ended it up with tales of the modern and open urban life. Japan, it seems, cannot and will not be held in a single state of mind.

THE MORNING WAS BRIGHT AND CLEAR, with only a slight chill in the air. Jon and I ate a full breakfast with the workers from Nagoya—the one was still dressed in his Hello Kitty sweatpants and shirt—and then walked up the hill to the train station. Jon was heading back to Tokyo to film the National Kendo Tournament, and I was taking the day off from hiking and going the opposite direction, to the town of Nakatsugawa to cash some traveler’s checks. I arrived at my destination in an hour, and waiting for me was my old friend Ichikawa-san, nearly eighty now with long, thin hair, a sparse beard, and an almost-disarming twinkle in his eye. He has looked more and more like a sennin, or “mountain sage,” every time we’ve met—the effect, no doubt, of a lifetime spent hiking the mountains and reading classical Oriental literature.

After catching up, Ichikawa-san drove me to the bank, and I changed my traveler’s checks into Japanese yen, an increasingly difficult transaction. Although I was now ready for some good conversation at a coffee shop, when I stepped back into the car, my friend, ever the observant mountaineer, noticed that I was walking with a pronounced limp. So, instead of the comfort of a coffee shop, he drove me to a local clinic to check out the blisters and so ward off any future disasters.

When people who are not used to travel become tired or get blisters on their feet, it is entirely because they have put on their footwear indifferently. Get good footwear, have them properly worn in, and do not hurriedly put them on. Make sure that they are neither too tight nor too loose. Again, when your feet are desiccated, hot, and thus cause you discomfort, you will get blisters. At such times, loosen the ties of your footwear now and again, cool your feet, and rest in a proper posture.

—Ryoko yojinshu

Soon I was seated in a small office while a young Dr. Saito examined my feet. He was clearly impressed—as were the nurses—with the size and number of blisters but pronounced me to be OK and advised a full day of rest. Taking a good look at the callous on my left big toe, however, he expressed a bit of curiosity as to how it got there and asked how long I’d had it. I explained that I practiced kendo—Japanese fencing—back in Miami, and he nodded approval and laughed. The nurses looked quizzical, so he stood up from his chair, grabbed an imaginary bamboo sword, and, in white coat and stethoscope, lunged around the small room two or three times, pushing off appropriately with his left foot. “Daigaku no jidai, sandan deshita yo.” (“In college, I was a third-degree blackbelt.”) We all laughed, and I limped out into the waiting room, to find Ichikawa-san wondering what all the stamping was about. “Excellent technique,” I explained, and off we went to a local Indian restaurant—dal with spinach, chicken curry, and mango juice—accented with an hour’s worth of reminiscences about our climbs together. Then it was back to the station, a heart-felt good-bye, and the return trip to Kiso Fukushima. In less than two hours, I was back at the Sarashina-ya, where I washed and dried more clothes and took a nice soaking bath. Later that evening I had a quiet dinner—Jon and the Nagoya workmen were all gone—and was off to bed.

MOUNT ONTAKE: Elevation 10,067 Feet

Not far from Kiso Fukushima stands the 10,067-foot Mount Ontake, one of the holiest mountains in Japan. Although it is only distantly visible from a few points along the Kiso Road, it dominates the spiritual landscape and is in some way there in the consciousness of everyone living in the post towns along this ancient route. During the summer months, the trails leading to the various summits are dotted with white-clad pilgrims, praying as they climb—walking as a religious rite. Although a very few may make the journey to the foothills on foot from their homes elsewhere in Japan, most will take cars or buses to one of the stations from which the trails to the top begin. Such buses or hired cars can be boarded at the train station at Kiso Fukushima, the trip taking forty-five minutes to an hour.

In early October of 1979, I was invited by my friend Ichikawa-san, a seasoned mountaineer, to make a day climb of Mount Ontake and readily agreed. I was staying at the Sarashina-ya, and he picked me up soon after breakfast in his small but comfortable Suzuki sedan. It was a clear day, cool for September, and as we drove along the foothills, we chatted about the origins of Ontake-kyo, or the Ontake religion.

According to Ichikawa-san, Ontake-kyo is not so much a centrally organized religion but is divided into a number of spiritual fraternities, or kou  , each headed by a set of leaders and subleaders and often accompanied by a shaman. My friend further explained that, in this religion, belief is not as important as practice, and that practice centers around prayers to the gods of the mountains, recitation of various sutras, and climbing the mountain itself. At certain times, a group makes an ascent, and individuals will ask an accompanying shaman, who will become possessed by one of the gods and guided by a priest, questions of deep importance to them. These are deeply religious experiences, and the shaman is often physically and psychologically exhausted by such possession. On the way to the Kaida Plateau, where we parked the car and started our walk, we passed a number of small, clean graveyards containing the spirits of believers from the past.

, each headed by a set of leaders and subleaders and often accompanied by a shaman. My friend further explained that, in this religion, belief is not as important as practice, and that practice centers around prayers to the gods of the mountains, recitation of various sutras, and climbing the mountain itself. At certain times, a group makes an ascent, and individuals will ask an accompanying shaman, who will become possessed by one of the gods and guided by a priest, questions of deep importance to them. These are deeply religious experiences, and the shaman is often physically and psychologically exhausted by such possession. On the way to the Kaida Plateau, where we parked the car and started our walk, we passed a number of small, clean graveyards containing the spirits of believers from the past.

At the Kaida Plateau, the trailhead for the climb, there is a large concrete building complete with comfortable benches, tables, chairs, snacks, and coffee, and a stunning view of the four peaks of the mountain, which has been worshipped since at least the seventh century. Only monks were permitted to climb it until the eighteenth century, when it was “opened” by the ascetic Kakumei, who likely would have blanched at the convenience with which we approached the mountain today.

Kakumei’s feelings aside, Ichikawa-san and I left the car in the parking lot, climbed the steps up to the rest station, and indulged in one more cup of coffee to get us on our way. A sign next to the exit encouraged us to use the facilities so as to have no chance to pollute the sacred mountain. This is not just for the hikers’ comfort; the practitioners of Ontake-kyo believe that the natural phenomena they personally experience on the mountain—the rocks, grasses, trees, and even the clouds and wind—are the abode and work of the gods and buddhas. This is a deeply felt and sincere belief, and not one to be taken lightly.

Our ablutions complete, we headed out, our only gear being light packs containing water bottles and snacks of rice crackers. The trail from the Kaida Plateau begins as a rocky, mildly sloping incline but quickly becomes steeper and steeper; small stunted trees surround the path, their roots sometimes providing footholds or a kind of riprap. Not far along, there is a small wooden structure, where a priest sells various amulets, talismans, and scrolls depicting the gods of the mountain, one of which I purchased and tucked securely into my pack. Continuing to climb, we sometimes passed groups of various sizes, pilgrims clad in white—including young children and the elderly—all helping each other along. “Gambatte ne!” (“Keep at it!”) Farther up the trail, we came across five or six pilgrims making mudras—symbolic symbols with their fingers—chanting mantras, and clapping to get the gods’ attention at one of the many sacred shrines along the way. Over the centuries, Ontake-kyo developed from a mixture of ancient mountain worship, Shinto, and esoteric Buddhism, and the influences of all of these are apparent at these sites. Here, there is a shrine dedicated to a Shinto deity; farther up, one enclosing a Buddhist saint; yet beyond that will be a statue of En no Gyoja, the founder of the Shugendo sect. Perhaps most prominent, though not necessarily in size, are the sites holy to Fudo Myo-o, the “Brightness King of Unwavering Mind,” an avatar of the Mahavairochana, the “Great Sun Buddha.” Holding a sword in his right hand to cut through our ignorance, he also carries a rope in his left to tie up our passions. As Ontake-kyo is a religion that syncretizes Shinto and Buddhism, Fudo Myo-o is also mystically related to Amaterasu Omikami, the sun goddess from whom the Japanese emperors descend. Thus, almost every step on this mountain participates in a mysterious liminal realm.

Gambatte ne! Keep at it!

The two of us continued on, sometimes passing up other climbers and pilgrims, once or twice passed up ourselves by groups of three or four octogenarian ladies all dressed in white, grasping their walking sticks, tiny rucksacks slung over their backs. They smiled and encouraged us to carry on and then disappeared around the next curve.

Stopping at each shrine where there were no pilgrims praying, we clapped our hands reverently to the gods in gratitude and respect. The dwarf conifers and pines had given out some time ago, so we trudged on over the rocky surface under a clear blue sky. After about four and a half hours, we finally reached the caldera of the old volcano. I had been smelling something sour for a while and, looking down into the crater, now understood why: plumes of fine sulfuric steam were rising from three or four places down inside, creating a vision of an entrance to hell. I nervously asked Ichikawa-san if this “dormant” volcano was maybe just a little bit more than that, but he laughed and informed me that there had never been an eruption in recorded history and that geologic evidence suggested that the last volcanic activity had been over six thousand years ago. I did not find the number “six thousand” to be very reassuring in terms of geologic time and suggested that I was ready to go back down. But no, first we hiked over to the main shrine on the peak, prayed to the gods of the mountain (you can imagine what my prayer was about), and then all too slowly headed back down.

On the drive back to the inn, Ichikawa-san told me about the flora and fauna of the Ontake area, some of the former of which are collected and made into small pills called hyakusogan, taken for everything from headaches to hangovers to stomach problems. They are supposed to be quite effective, and we stopped at a local store and bought a bottle each. As to the fauna, the most interesting perhaps are the koi that live in a small pond located near the base of Mount Ontake. Thanks to the spiritual quality of the surroundings, they live unbelievably long lifespans. One of these carp, named Hanako, died here in 1977 at the great age of 227, making her the oldest known vertebrate animal in recorded history. I asked Ichikawa-san about maybe stopping to take a sip from the pond, but, alas, it was not on our route.

Back at the Sarashina-ya, we shared a bottle of sake and a fine dinner prepared by Mineko and talked about the day. Ichikawa-san then drove back home, and I took a good long bath and crawled under my futon.

Two weeks later, I was home in Miami, drinking a cup of coffee at my cluttered desk. Picking up the newspaper, I found an article that caught my attention. On October 28, the supposedly dormant volcano Mount Ontake erupted, sending huge clouds of black smoke into the sky, and was expected to continue volcanic activity for some time. I looked up at the scroll of Fudo Myo-o and the gods of Mount Ontake hanging on my wall, said a brief prayer of thanks, and decided that my break time was over.

A NUMBER OF YEARS LATER, I was back in the Kiso and once again staying at the Sarashina-ya. There was a knock on the door of my room announcing dinner, but rather than Mineko, it was her husband, Ando-san. (Mineko has explicitly requested that I call her by her given name; Ando-san is a bit more reticent and shy and prefers his family name.) Dinner was ready, he said, but added that sometime later there would be a service at the local Ontake-kyo temple and asked if I would like to attend. He himself, although a shaman, would be unable to enter the temple as his second granddaughter had just been born, making his presence taboo. I assured him that I would be more than pleased and followed him down to the dining hall.

The dining room was crowded that night, so for convenience’s sake, Mineko had put me at the same table as the only other foreigner there, a fiftyish man from the States. As we talked over dinner, he informed me that he was a travel writer and was preparing an article on the Kiso area. Although he spoke almost no Japanese and seemed to be picking at the local food, he was gamely following parts of the Nakasendo, so I quickly let him know about the service at the temple and encouraged him to come along. He was not particularly enthusiastic, but I persisted, and, after our repast, we found ourselves in Ando-san’s car, heading toward the temple on the outskirts of the post town. Soon, we were dropped off at the entrance to the temple, our gracious driver telling us that he would pick us up at the conclusion of the service.

The Hyakumataki temple is a wood and clay structure with a gray tiled roof, and not very large—certainly not as large as some of the more elegant Zen and Shin temples that dot the Nakasendo. Inside, cushions were set on the floor for perhaps forty to fifty people at the most and, facing these, a platform on which, this evening, along with two huge dark wooden statues of the men who “opened” the mountain, was a very large polygonal stack of cedar planks, each about a foot and a half long and an inch and a half square. Above this stack of planks hung the holy white folded papers indicating the sacred in the Shinto religion.

As we all entered the temple, we were each given a white jacket to symbolize purity of mind and a cedar plank of our own. This would be an o-harai, a ceremony of cleansing. My American acquaintance and I were ushered to the front row of cushions, on each of which was a booklet of sutras written in Sino-Japanese that would be chanted throughout the ceremony. Soon, when the last of the congregation had been seated, a white-robed priest and his attendants mounted the platform, and the chanting began. At first only the priest chanted, his attendants blowing conch shells and beating small drums, but later we were all to join in, and the chanting became faster and more intense. Suddenly, the cedar planks were ignited into a huge bonfire, the priest seemed to go into a trance, and the accompaniment grew louder and louder. I was doing my best to keep chanting along with the unfamiliar sutras, but they were being recited faster and faster, until finally we got to the Hannya shin-gyo, or Heart Sutra, with which I was familiar. Glancing over at my companion, I could see that he was staring straight ahead and looking more than a little uncomfortable.

Throughout the ceremony, the participants had been rubbing the cedar sticks they had received on the part of their bodies that had been causing them trouble—on their heads, for example, if they had had headaches or worries, on their abdomens in the case of stomach pains, or near their eyes if having sight problems. In my case, I had been rubbing my left leg with my stick as we chanted along, hoping to ease the limp I had developed on this hike.

Now, one by one, as the chanting grew more intense, each member individually mounted the platform, bowed to the fire, threw his or her stick into the leaping flames, and the priest then whispered to him some spiritual advice. My turn came. I crawled up in front of the fire, made my obeisance, tossed in my stick, and leaned toward the priest, as he whispered in my ear, “Kaze wo hikanai yo ni, ne. Kiso wa goku samui yo.” “Don’t catch a cold, now. The Kiso’s really cold!” This was not exactly what I expected, but it was certainly thoughtful of him, and I bowed and crawled back down to my cushion. Next it was my companion’s turn, but when I motioned to him to go up, he shook his head no. I encouraged him again but got the same stiff response and so explained to the usher that he would not be participating. The usher gave me a quizzical look but then moved on to the next member of the congregation, and I joined back in with the Heart Sutra—thankful that this was the one repeated over and over during the o-harai.

Finally, the flames died down, the priest gave a short homily, and the temple was empty again. Outside, Ando-san was waiting for us and drove us back to the inn as we chatted about our experience. On the way up to our rooms, I asked my American companion, who was still looking a bit stiff and silent, why he hadn’t joined in. This had been, after all, a great opportunity to get at travel writing from the inside. “No,” he said, “I’m an Episcopalian,” and shut his door.

Back in my own room, I couldn’t sleep. I felt oddly cleansed and, even though it was going on toward midnight, filled with energy. Sitting on my miniscule couch for a while, I thought over the evening’s events and wondered what difference it makes what a person worships, as long as it’s curative and for the good. Outside my window, the Kiso River rushed by in swirls and eddies, on its long way to the sea.

NOW THAT MY BLISTERS had gone down a bit, I was regretting that I would not be making the climb up Mount Ontake this year but was thankful for the rest. Kiso Fukushima is the halfway point of the Kiso Road, and although I hadn’t being breaking any speed records, I was happy to have had a day of catching my breath.

After the television weather report—predicting the day to be clear and unseasonably warm—there was a program on expert coffee making and competition, which I watched with intense interest, remembering my humbling lesson on tea making when I first arrived in Japan. My apartment had been in a small local neighborhood of Buddhist image carvers, a public bath, and a tiny tea store run by a middle-aged man who was missing a front tooth and with a perpetual three-day beard long before it became fashionable. Entering his shop, I had asked for some of his very best tea and been greeted by a blank stare and the question, “Do you know how to make it?” Slightly taken aback, I had replied, “Of course. You boil water and pour it over the tea.” He then asked me to wait a minute or two, patiently boiled water in a cast iron tea kettle, let the water cool until he could touch the bottom of the kettle with the palm of his hand, filled a small tea pot with gyokuro—the highest grade tea—and poured what seemed to be only two or three sips into a small porcelain teacup. “Don’t gulp,” he said, knowing that that was exactly what I was going to do. Slowly emptying the cup, I could taste nothing until a subtle aftertaste seemed to go right up the back of my head. I was dumbfounded. Apologizing for my presumptuousness and thanking him for taking the time to provide me with such an exquisite experience, I ordered a small paper bag of an appropriate tea for everyday drinking. As I bowed my way out of the door, he gave me a polite smile and continued his work. This had been the first but not the last lesson I would learn about the extreme care and thoughtfulness the Japanese take in what might seem to be the most commonplace affairs—making tea and coffee included.

After jettisoning some more superfluous clothes and repacking my backpack, I headed down to the foyer, where I met Ginny Tapley Takemori and her husband, Tadashi. Ginny had been one of my editors at Kodansha International and is now a translator and writer; Tadashi is a physicist teaching at a university north of Tokyo. Both are avid hikers. When Ginny had heard that I was coming to Japan for the walk, she volunteered to accompany me for a two-day portion, and I was pleased to have their cheerful company, but at the same time worried that I might slow them down. I explained about the status of my feet, but they were undeterred, and, after tea and cookies provided by Mineko, we thanked our hosts and walked out onto the Kiso Road.

The road out of Kiso Fukushima soon connected with the national highway, but the river was rushing along noisily down to our right, the mountains coming right down to the river were full of color, and the air was still cool and clear. As elsewhere, the Kiso Road now paralleled, now diverged from the national highway, and the three of us even found some smaller paths that had been a part of the original road in the distant past. After an hour of hiking, we came upon a juncture where the highway was being renovated—this was marked by a hundred or so football-sized yellow rubber ducks attached to the side rail—and we turned off to a smaller road marked by a wooden sign announcing it as the “Old Nakasendo.” There we discovered a narrow footpath through some vegetable gardens leading up to a tiny shrine enclosing a barely visible statue of Batto Kannon dedicated to Kiso Yoshinaka’s horse. This horse had been able to understand human speech, it is said, and had been remarkably powerful as well. But when Yoshinaka had given it the command to jump up to a cliff, he—Yoshinaka—had mistaken the distance. The horse jumped exactly as far as Yoshinaka had commanded but missed the cliff due to Yoshinaka’s mistake and had fallen to its death. Yoshinaka grieved for the horse and set up the Batto Kannon shrine to pray for its salvation. According to a signboard next to this diminutive edifice, the original shrine had been established a mile or so from its present location but then moved intact with the construction of the Chuo-sen.

After another half hour along the national highway, we arrived at another “Pray to Mount Ontake from Afar” location, but by this time clouds had gathered, and the sacred mountain could not be seen. Still, there were a few pilgrims who had stopped their cars and were praying, their joined hands clasping their rosaries, and their gazes off into the distance. Observing the dedication and faith of these people, I once again regretted not having been able to make the climb.

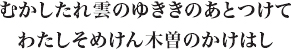

Finally, as the cliffs along the river became higher and higher, we arrived at the site of the Kiso Road’s most famous kakehashi, or “suspension bridge,” a “bridge” that did not span the river but ran along sideways, parallel to the precipice. From the year 1400 to 1410, a new road had been opened along the Kiso River, and it is said that three hundred fifty feet of wooden planks held together with vines and ropes had been suspended along the cliff. This kakehashi had been repaired repeatedly over the years, but in 1599, Toyotomi Hideyori commanded one of his generals to do major repair. This would be the bridge that had so frightened travelers that their knees shook as they crossed from one end to the other.

Then, in April of 1647, a wayfarer accidentally dropped a pine torch while crossing the bridge, and it burned up completely and collapsed. Consequently, the Yamamura and Chimura clans were given orders and monies from the Owari fief to build a stone wall along the cliff for the bridge, and this was completed the following year. Even today, there remains an engraving, visible in the cliff wall, that states, “This rock wall completed in the sixth month of 1648.” Rock wall or not, it must have continued to terrify those who walked across it. The poet Basho crossed the bridge in 1688 at the age of fifty-four and wrote,

The suspension bridge!

One’s life entangled

in vines and creepers.

His disciple Etsujin added,

The suspension bridge!

The first thing you think of:

meeting a horse halfway.

In 1741 there was yet another extensive repair and innovation. Then, in 1879, a certain Iseya Denbei built a bridge to the opposite shore, on which pilgrims to Mount Ontake from Owari and Mino paid a fee and were allowed to cross over. The bridge had been fashioned after the Great Bridge at Sanjo in Kyoto and had a balustrade in the elaborate Chinese T’ang dynasty style. The bridge itself was some 190 feet long and 11 feet wide. Unfortunately, it was washed away in a flood on the sixteenth day of the seventh month in 1884, and passengers were reduced to making the difficult passage across the river by boat once again.

Again, however, in 1910, another bridge was built by a private citizen on the same spot as the one that had washed away, using the newest construction techniques of wire ropes. The fare was set at two sen. Nonetheless, forty years later the bridge was deemed to be unsafe, and the authorities built a new bridge of the same design on the same spot. Finally, the current bridge was constructed in 1963, and it is this bridge that Ginny, Tadashi, and I crossed to the other side of the Kiso.

The area here is full of ancient trees—chestnuts and pine—and unopened chestnuts litter the path. Dominating the immediate view is a huge stone marker donated by Admiral Togo, noting that the emperor Meiji stopped to rest here. There are also two memorial stones engraved with haiku by Basho and Shiki. It is surprising to know that Shiki, whose health was always so delicate, could put up with the rigors of the Kiso Road, but in 1881, at the age of twenty-five, he traveled the road and wrote the following entry in his Kakehashi no ki.

Just at that time there was an early summer shower on my Kiso journey. As I stepped out of my inn, the rain temporarily let up. Taking this moment and hurrying along, I was still chased by passing showers; then, taking a break under the trees, the rain would stop again. At any rate, I went along, being made sport of by the rain, until I reached the suspension bridge. At the sight of them, both cliffs looked quite dangerous, appearing to have been axed out perhaps forty or fifty feet high like a folding screen. The moss seemed to have been growing there in the moist air since the age of the gods, its light green covering spotted casually here and there with azaleas—a scene that could have been painted by artists from the Kano or Tosa schools. Taking a step forward and looking down, the force of the river swollen by the early summer rains swirled in waves struck by currents of cloudy mists, the echoes of which reverberated against the huge crags so that when I returned to the teahouse, sat down on a folding stool, and closed my eyes, the ground continued to shake for a little while.

I went to pay my respects to old Basho’s stone monument and crossed the tiny rainbowlike bridge as though I myself were floating in the ether. The soles of my feet felt cold, and I was unable to step along with a good stride; but looking about, I was able to see the traces of the old suspension bridge. I had known about the place before, but today, with the rocks piled up one on top of another, coming and going was carefree from the very start. Still, the ancient scenery must have been one of twisting and crawling vines and creepers.

The suspension bridge!

At this dangerous spot,

mountain azaleas.

The suspension bridge!

The river is never filled:

early summer rains.

Long ago,

who would follow along

the coming and going of clouds?

But I’ll give it a try

on the Kiso no kakehashi.

About one and a half kilometers from the site of the old bridge, there is a confluence of the Kiso River and the Shinchaya River. During the Meiji period, there had been a teahouse here—the Yayoi Teahouse—where travelers would stop to drink tea and sample the local delicacy, bracken mochi. The following story is still told.

A long time ago, on the bank of the Shinchaya River, there was a teahouse called the Yayoi Teahouse, and one day a mendicant priest stopped to drink tea while resting from his travels. Just then, a man passing by stopped to talk with the master of the teahouse.

“Hey, did you see it? A pumice stone floating down the river again?”

“Sure, I saw it,” the master replied. “We’ll be lucky if something bad doesn’t happen again.”

The priest heard these remarks and promptly asked, “What’s this business about a pumice stone and the something bad happening?”

According to what the teahouse master said, there was a stone that floated along the river from the suspension bridge to Nezame no Toko, and just as you started thinking how strange that was, the stone would immediately return to the suspension bridge. The master then explained in detail how when this stone made its appearance in the river, someone would inevitably drown, or there would be some other unfortunate occurrence.

The priest then said, “I’ve done ascetic practices from journey to journey for a long time, but this is the first time I’ve ever heard of anything like this. I’ll try to do something to stop this stone with the strength I’ve gained from my training.”

So saying, he took a brush from the ink-and-brush case at his waist and wrote down a poem on a narrow strip of thick paper.

The thread connecting

the bridge and teahouse

stop the flow

of the floating

stone.

The words “bridge” and “teahouse” were written in secret words to help the spell.

Just as the priest had said, as soon as the words were written down, an invisible thread stretched out, the strange floating pumice stone no longer floated down the river, and unlucky events no longer occurred in the village.

It is said that the stone remains today in the upper reaches of the oni no fuchi, “Demon’s Abyss.”

The three of us followed along a narrow road overlooking the river, crossed a bridge parallel to one once used as an old narrowgauge railroad, and walked into Agematsu. There is a nice little restaurant across from the railroad station, and we stepped inside for sushi and beer to pick up our spirits. The master of the place was a little surprised to find that two of his three guests were foreigners with backpacks who spoke Japanese—Agematsu is not exactly a cosmopolitan town—but welcomed us with a smile and seemed to have understood our predisposition for cold beer even before we had walked in. In seconds, we were kanpai-ing to a good day’s walk. We made short work of our sushi and headed on to the Sakaju Inn and the ever-smiling o-kami-san, the seventy-nine-year-old Mrs. Hotta.

COURSE TIME

10 kilometers (6.25 miles). 3 hours.