両国

RYŌGOKU

Ryōgoku is a major center for sumō. Host to three fifteen-day tournaments a year, the area is well known as home to many training stables. As you wander through the neighborhood, you may spot restaurants serving chankonabe, a dish traditionally eaten by wrestlers, and statues and monuments related to sumō, as well as rather large guys going about their daily business. The area is also known for the summer fireworks festival dating back to 1733, which is held on the last Saturday of July upstream from the bridge. If you need a break, there are many excellent restaurants in the vicinity of the arena and station. With its parks and museums, this area is a joy to stroll through.

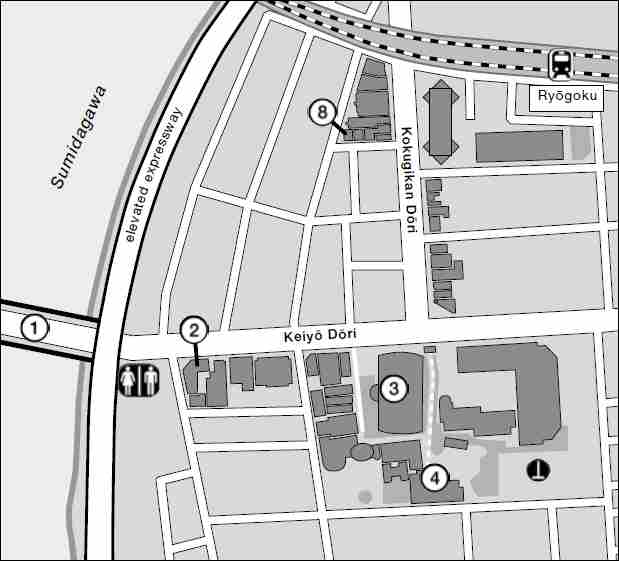

DETAIL 1

The original Ryōgokubashi, built in 1657, was the first bridge to span the Sumidagawa. Now that it was no longer necessary to rely on ferries, development greatly increased east of the river. Originally called simply Ōhashi, “Great Bridge,” it was the largest bridge in Japan, with a length of 574 feet (175 meters) and width of 23 feet (7 meters). The name Ryōgokubashi, “two provinces bridge,” came later, referring to the fact that it connected two provinces, Musashi on the west bank and Shimōsa on the east. The bridge was rebuilt of steel in 1904, destroyed in the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923, and rebuilt in 1932, with further renovation in 2008. Interesting design elements include the small decks that extend over the water from the pedestrian walkways, art deco globes at each end of the bridge, and a design motif on the rails in the shape of the fans used by sumō referees. If you cross the bridge to the west, you will find where the Kandagawa meets the Sumidagawa, an inviting stroll along the Kandagawa will take you to Akihabara. In the animated feature Hokusai’s Daughter, the bridge is crossed several times by various characters.

This restaurant founded in 1718 specializes in boar, bear, and deer meat. If you have a taste for wild game, you may want to visit. The name simply means a place that sells this kind of meat. Despite Buddhist prohibitions on meat consumption, such restaurants existed in several cities in the Edo period. The rationalization was that the meat was eaten for medicinal purposes. On the outside of the building is a simple sign with a sculpture of a boar above the name. They have English-speaking staff on hand.

Ryōgoku Fireworks Museum / Ryōgoku Hanabi Shiryōkan 両国花火資料館

Ryōgoku Fireworks Museum / Ryōgoku Hanabi Shiryōkan 両国花火資料館

Japanese fireworks are world famous for their spectacular beauty and variety. Fireworks were introduced into Japan by English merchant John Saris in 1613 and soon became popular. The famous annual Sumidagawa fireworks display began in 1733 as part of memorial activities for those who had died in a plague. Open since 1991, the museum has displays on how fireworks are made and on the devices used to launch them, as well as artwork and photographs relating to festivals.

This Jōdoshū Buddhist temple was established in 1657 as a memorial to the dead from the Great Meireki Fire who were unidentified or had no family to claim their bodies. There is a monument to them called the Banninzuka, or “Mound of a Million Souls.” Ekōin has also long been associated with memorials for animals. Shōgun Tokugawa Ietsuna’s horse was memorialized here, and Ōta Nampo’s Ichiwa Ichigen makes reference to six hundred cats buried here after an epidemic in Tokyo. One building, both unusual and controversial, is the three-story Ekōdō, a memorial hall for the remains of dead pets. Such memorial halls and sculptures are not the norm in Japan. There are memorial sculptures with animal themes including one for cats and one for fish. Another sad monument on the temple grounds is the Mizukozuka, “Mound of the Stillborn,” for infants who died in birth, miscarriage, or by abortion.

Ekōin was the location for many sumō tournaments from 1833 until the first Ryōgoku Kokugikan opened in 1909. The Chikarazuka, or “Mound of Strength,” is a large stone monument where part of the hair cut when famous sumō wrestlers retire is buried. Enter the grounds from the main street, Keiyo Dōri. Look for the red pillared gate with an unusual curved roof. While there is a back gate on the south side, it is often locked. This temple is on the Tokyo 33 Kannon Pilgrimage route.

RYŌGOKU WEST

RYŌGOKU EAST

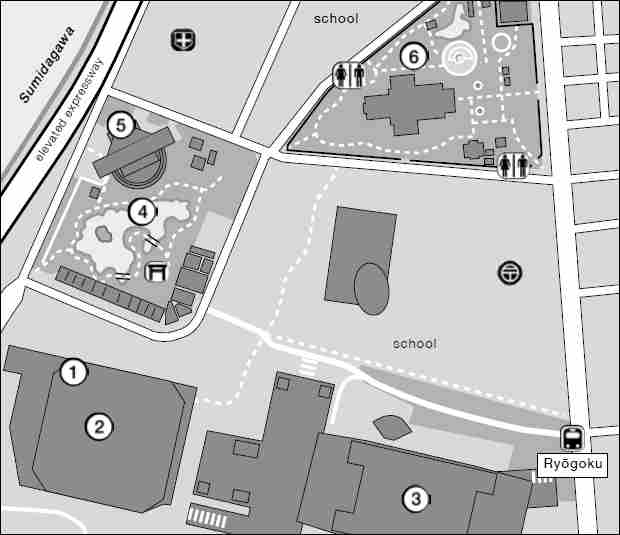

RYŌGOKU DETAIL 1 WEST

Honjo Matsuzakachō Park [Kira Residence Remains] / Honjo Matsuzakachō Kōen [Kira Tei Ato] 本所松坂町公園 [吉良邸跡]

Honjo Matsuzakachō Park [Kira Residence Remains] / Honjo Matsuzakachō Kōen [Kira Tei Ato] 本所松坂町公園 [吉良邸跡]

This small city park is the site of the famous revenge attack in the story of the Forty-Seven Rōnin, dramatized in puppet theater, kabuki, ukiyo-e prints, and over seventy live action movies. When the property was being subdivided and sold in 1934, a small corner of the extensive grounds was obtained by the neighborhood. It was donated to the city and opened as a park in 1935. While the rōnin are portrayed as heroes in the highly fictionalized dramas of the Forty-Seven Rōnin, their victim Kira was quite respected in this area. The grounds contain a small shrine and the well where Kira’s head was washed. A plaque lists those who died defending Kira in the attack, and each year on December 14 a ceremony is held in their memory.

RYŌGOKU DETAIL 1 EAST

Memorial to the Birthplace of Katsu Kaishū / Katsu Kaishū Seitanchihi 勝海舟生誕の地 記念碑

Memorial to the Birthplace of Katsu Kaishū / Katsu Kaishū Seitanchihi 勝海舟生誕の地 記念碑

This monument in a corner of Ryōgoku Park marks the birthplace of Katsu Kaishū, who played a major role in the Meiji Restoration and the opening up of Japan. Everything is in Japanese, but much of the exhibit consists of photographs and images, so those interested in mid-19th-century Japan will recognize a good deal of what they see.

The “Rat Boy” of Ekōin

One interesting monument at Ekōin is dedicated to Nakamura Jirokichi, more commonly known as Nezumi Kozō, “Rat Boy.” He was a bit of a Robin Hood character who robbed over one hundred wealthy samurai estates before being caught and executed in 1831. The memorial is easy to find as there are two stones; the second one is provided for people to chip off a piece as a good luck charm. This helps to prevent damage to the main stone, which has been replaced several times. There is a plaque with the outline of a thief sneaking away. There is also a memorial to another thief: a cat that would steal money and bring it to its impoverished invalid owner. The cat was caught and killed by staff at a store it had been stealing from. The store’s owner heard the story and helped pay for this memorial.

Lion-dō is a family business established in 1907, patronized mainly by the local professional sumō wrestlers. The store sells what would elsewhere be a very ordinary commodity, men’s everyday clothes. Nothing fancy, but they have an unusual specialty: the shop is filled with clothing for very, very large men. If you are looking to buy something for an unusually large person, be sure to have metric measurements handy.

In a neighborhood filled with chankonabe restaurants, this is considered one of the best and is likely the oldest as it was founded in 1937. Chanko Kawasaki serves proper chankonabe made with free-range chicken and lots of fresh vegetables. Founded by a former sumō practitioner, it is carried on as a family business. This is not a place to dash in for a bite as it takes a little time, so sit back and relax. The cooking is done in front of you and the owners will let you know when it is ready. The restaurant was rebuilt in 1949 and stands out from the newer buildings in the neighborhood by its age and one-story height, but also by the vegetation out front.

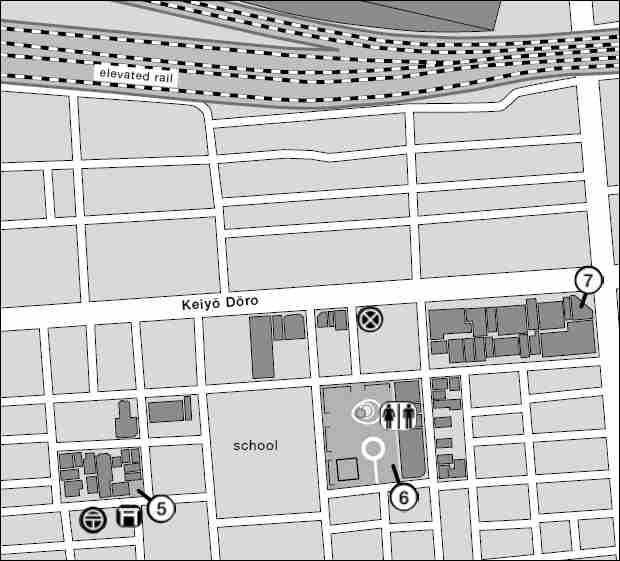

DETAIL 2

Sumō Museum / Sumō Hakubutsukan 相撲博物館

Sumō Museum / Sumō Hakubutsukan 相撲博物館

This is a small, free museum of professional sumō. The museum opened originally at the Kuramae Kokugikan in 1954. It was transferred to the present location when the Ryōgoku Kokugikan opened. On dispay are photos, woodblock prints, documents, books, referee’s lacquered fans, aprons worn by rikishi (sumō wrestlers) at tournament ceremonies, memorabilia, and more.

During the grand sumō tournaments and some other events, the museum is only open to ticket holders.

http://sumo.or.jp/EnSumoMuseum

http://sumo.or.jp/EnSumoMuseum

RYŌGOKU DETAIL 2

Ryōgoku Sumō Hall / Ryōgoku Kokugikan 両国国技館

Ryōgoku Sumō Hall / Ryōgoku Kokugikan 両国国技館

This facility is used for sumō tournaments, and at other times for other sports and events. Three major tournaments, called honbasho in Japanese, are held here each year: around the New Year, in the summer, and in the fall. The building seats over 11,000 spectators. In the Edo and early Meiji periods, sumō bouts were held mainly at Fukagawa Hachimangū and later Ekōin. This is the third location for the Kokugikan, the first having been built next to Ekōin in 1909. After World War II the Kokugikan was requisitioned by the occupying forces and sumō returned temporarily to being held at shrines. In 1954 a new Kokugikan was built in Kuramae on the other side of the Sumidagawa. Finally after several decades, the sport returned to the Ryōgoku neighborhood in 1985. The building also stores food and water for use in case of major emergencies.

▲ The dioramas of the Edo-Tokyo Museum lay out the city as it once was.

▲ The modern Sumida Hokusai Museum honors one of the area’s most famous artists.

Edo-Tokyo Museum / Edo Tokyo Hakubutsukan 江戸東京博物館

Edo-Tokyo Museum / Edo Tokyo Hakubutsukan 江戸東京博物館

I generally recommend a visit to this museum early on your trip to Tokyo to learn, or refresh your memory, about the city. Designed by Kikutake Architects and opened in 1993, the museum is laid out so you start at the founding of the city called Edo, then travel into the era when the city was renamed Tokyo and down to the present day. The exhibits will help you have a better conceptual framework to understand Tokyo and the transformations it went through over the centuries. You access the main display areas by taking the elevator to the entrance on the sixth floor, then cross a full-scale replica of the original Nihonbashi to a display of very large dioramas of the early days of the city. From there you go down to the next level, which has reproductions of shops, homes, and more from the Edo period. And more? Yep. Test your strength at hefting a pair of sewage collector’s buckets on a carrying pole, lift a fireman’s matoi, or perhaps enjoy a performance of shamisen, kabuki, or rakugo on the stage. Continue under the bridge and take the path on the left to see the history from 1868 to the present. The first floor is usually the site of special exhibits. The gift shop sells an attractive catalogue of the permanent exhibits.

There is a branch museum, the Edo-Tokyo Open-Air Architectural Museum, listed in the Day Trippin’ section of this book.

https://www.edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp/en/

https://www.edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp/en/

Former Yasuda Gardens / Kyū Yasuda Teien 旧安田庭園

Former Yasuda Gardens / Kyū Yasuda Teien 旧安田庭園

This former daimyō garden was given to the city by the family of financier Yasuda Zenjirō after he was assassinated in 1921. The park was almost completely destroyed by the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923 but was restored by 1927. It burned again in the firebombings of World War II. The heavy pollution of the postwar period did additional damage. It was again restored in 1971. A large portion of the center of the garden is devoted to a large pond. Originally the pond was connected to the river, so it rose and fell according to the tides. These days that connection no longer exists, but the pond still rises and falls via the action of pumps. This small garden has several benches and houses an old shrine.

Japanese Sword Museum / Tōken Hakubutsukan 刀剣博物館

Japanese Sword Museum / Tōken Hakubutsukan 刀剣博物館

Designed by Maki Fumihiko, the museum is operated by the Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords. Originally opened in Shinjuku in 1978, the museum was moved to this larger three-story location in 2018. Admission is free except for the third floor exhibition space. There is also a rooftop garden with a view overlooking the Kyū Yasuda Teien.

https://www.touken.or.jp/english/

https://www.touken.or.jp/english/

Yokoamichō Park / Yokoamichō Kōen 横網町公園

Yokoamichō Park / Yokoamichō Kōen 横網町公園

This park includes the Cenotaph Hall in memory of victims of the Great Kantō Earthquake, which later came to also memorialize the dead from the World War II firebombings of Tokyo. During the fires from the 1923 quake, tens of thousands fled to this location, which at the time was a large open area. The flames from the surrounding area were so hot that some 38,000 are estimated to have perished here. Starting at midnight of March 9, 1945, Sumida Ward was again subjected to fires from planes dropping incendiary bombs, killing large numbers of civilians in one night. In the park you can see warped and melted steel from the burned buildings. Each March 10 a memorial service is held for the dead. The unidentified remains for an estimated 58,000 who died in the earthquake and 105,000 from the firebombings are interned here. The Memorial Museum has exhibits about the horrors of the fires. There is also a peace monument with the names of some 100,000 civilians who died in the war, a monument to Koreans who died in the quake, a garden, and a memorial to children.

http://www.tokyo-park.or.jp/park/format/index087.html

http://www.tokyo-park.or.jp/park/format/index087.html

https://tokyoireikyoukai.or.jp/multilingual/en.html

https://tokyoireikyoukai.or.jp/multilingual/en.html

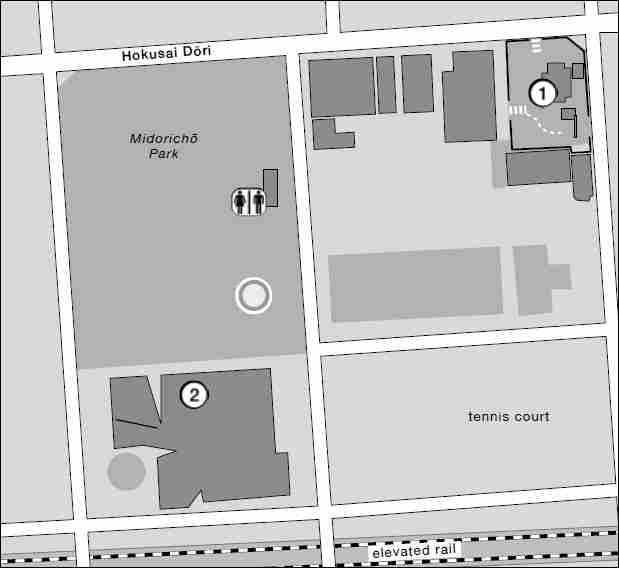

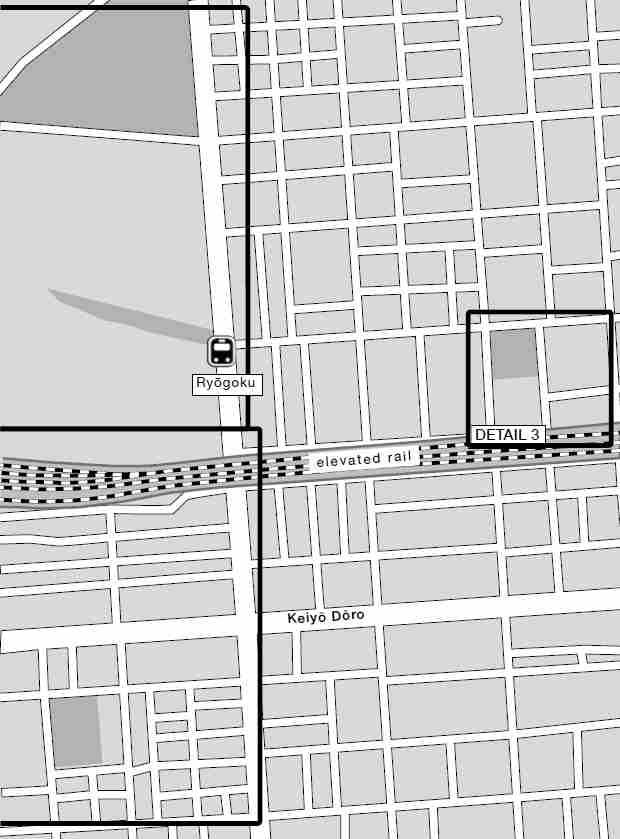

DETAIL 3

Nomi no Sukune is venerated as the legendary founder of sumō, so it is no surprise there is a shrine to him in Ryōgoku. In the Nihon Shoki there is the story of how, upon request of Emperor Suinin, he defeated and killed the boastful Taima no Kehaya in one-on-one combat. The Nihon Shoki also recounts how he convinced the emperor to substitute clay figures for actual human sacrifices in imperial graves. The story may have been influenced by Chinese lore; while clay figures have been found at many high-ranking gravesites, archaeologists have yet to find signs of human sacrifice at any such sites. The shrine is managed by the Japan Sumō Association.

Sumida Hokusai Museum / Sumida Hokusai Bijutsukan すみだ北斎美術館

Sumida Hokusai Museum / Sumida Hokusai Bijutsukan すみだ北斎美術館

Designed by Sejima Kazuyo and opened in 2016, this entire museum is devoted to the life and work of Katsushika Hokusai. The famous ukiyo-e artist was born and spent almost all of his life in this area. The museum incorporates modern technology to enhance viewing of the prints. Select prints are displayed on touch screens that allow you to zoom in to details on the images. This helps the viewer to appreciate both the original designs and the craftsmanship that the carvers employed in transferring the drawings to woodblocks. There are four floors: on two of them the museum hosts several temporary special exhibits a year; so depending on the dates of your stay, you may be able to see more than one. The special exhibits require an additional fee. The museum also has a library and gift shop.

RYŌGOKU DETAIL 3

NOTE: This area is reached either by following Hokusai Dōri or by going eastward along the north side of the train tracks, away from the Edo-Tokyo Museum.