CHAPTER ONE

Deep Code

OLD ERIN

— c 1800–1850 —

So listen carefully, and you’ll hear a true story that could never,perhaps, be equalled by any of those fictional ones that people compose with such care and skill.

Viewed from the heavens – perhaps from heaven itself – Ireland, already listing at an angle in northern waters, seems barely to cohere. Claws of fire, ice and water, acting when millennia rather than men marked out units of time, left enormous rents in much of its shoreline. In the south, around counties Cork and Kerry, huge fjords slice inland along either side of sandstone mountains. So deep and sharp are these rasps of salt water that, to the casual observer poring over a map, it would seem that all that lies between Killarney and Mizen Head is at risk of breaking off and drifting away across the chilled Atlantic. On the west coast proper, massive elongated indentations filled by deep lakes outline a tell-tale scar running through the counties Galway and Mayo and remind one how a powerful force once attempted to wrench everything between Clare and Kilala from the mainland. But it is in the very far north, north even of the most northern point of what became Northern Ireland – where Donegal turns its back on Derry – that the gods appear to have come closest to achieving their objective.

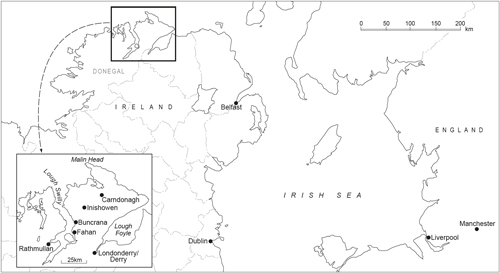

Inishowen Peninsula, Ireland

Malin Head, nearer to Iceland than is Belfast to Berlin, marks the northernmost extremity of what, at first glance, seems like an island bracketed by formidable mountains running down its eastern and western shores. Yet, despite the Gaelic prefix, inis (‘island’), Inishowen is in fact a peninsula, albeit one of unusual upside-down triangular shape with the apex pointing perversely south. Attached to the mainland and nestling wholly within the confines of Donegal, Inishowen, about 25 miles long and broad at its widest point, lies between the two most idyllic inlets in the Atlantic world. But, for all the difference they make, Lough Foyle, which describes the eastern boundary of the peninsula, and Lough Swilly, which marks its western extremity, might as well contain an island. Inishowen was, in many ways, a world apart.

On summer days, beneath clear skies and with mouths agape in the unfamiliar heat, the loughs easily take in the sparkling blue and foaming white of the ocean along with huge shoals of fish in search of placid waters in which to feed. But in midwinter, with jaws clenched against driving rain and wind coming in off the open Atlantic, even the sheltered lower reaches of the loughs seem encased in great sheets of impenetrable grey steel. From the heart of the peninsula, short but surprisingly strong rivers tumble down steep mountain-sides and then strike out across small fertile coastal flats until they reach the shores of the nearby loughs. Behind them for many centuries bogs, caves, fountains, glens, lakes, nooks, ravines, springs and valleys lay hidden in forested thickets of beech and oak; indeed most are there still, changed.

Yet, for all that they hold in common, the loughs resent being known only for locking the peninsula into position. In fairness, they do offer much more. Swilly, in particular, known to the ancients as the ‘Lake of Shadows’, has as many mysteries as it has surprises. About half-way down its course from the ocean, on the eastern shoreline, near Buncrana, where the returning salmon glide into the river to spawn, it throws up what looks like an enormous hill blocking the passage south. But daunting as Inch Island and the surrounds may seem at first glance, they herald the appearance of what is, arguably, Inishowen’s loveliest and best-kept secret. Opposite the island, back on the mainland, looms an elongated mountain often shrouded in mist with a dome of black rock that is forever glistening with moisture. On its seaward side, the Scalp overlooks the fertile fields of Lower Fahan (‘Fawn’ or ‘Fahn’) and, beyond that, a scimitar-shaped beach of inviting white sand which, when the sun is out, can be seen stretching lazily for many a mile. And beyond all of that, behind the Scalp, hides yet another delight, Upper Fahan, which tumbles down onto the greenest of undulating folds.

It was in these seductive environs, in the sprawling parish of Shandrim of Lower Fahan, on the thinner soils immediately below that scowling fastness of the Scalp, that Jack’s father, William McLoughlin, was born into a poor Catholic farming family in early 1823.1 Like most other venerable families in and around Buncrana, including the once-mighty Dohertys and the Hegertys, the McLoughlin clan (or sept) traced its roots back to the earliest rulers of the peninsula and, with much greater precision, to the times of Patrick himself. Indeed, it was shortly after the fifth-century conversion of Owen (‘Eoghan of the O’Neills’) by the Saint himself that the 300 square miles of greenery wedged between Foyle and Swilly took on the misleading moniker of Inishowen.

The McLoughlins, like most of the established inhabitants of Inishowen an offshoot of the founding Owens, formed an important part of the entrenched, intermarried yet frequently warring factions that had competed ceaselessly for control of the peninsula for hundreds of years.2 But they, no less than any other notables, were never fully isolated from distant external influences. Inishowen’s strategic location guarding the northernmost approaches to Ireland ensured frequent collisions with inward-bound foreigners. Some of the newcomers, like the friendly Scots whose homeland just across the water was visible from Malin Head on a clear day, were largely welcome. Others, like the fearsome Viking invaders of the ninth century who swept into the lochs from afar in their long boats, were not. Both groupings, it is now claimed, contributed to the genetic makeup of the McLoughlins and, perhaps, helped shape some of the clan’s own, often ferocious, soldier-sailors. Between the mid-eleventh and thirteenth centuries the McLoughlins were the undisputed rulers of all that lay between Loughs Foyle and Swilly.3

In retrospect, however, Ireland and Inishowen’s most formidable tormentors came not from the north or even from the south as did the Normans, but once again from just across the sea, from the east. From the moment that Henry VIII broke with Rome and established himself as head of the newly founded Church of England, in 1534, strained relations between Catholic Ireland and Protestant England were almost inevitable. The resulting tensions, transmitted into Catholic France and Spain, which had political objectives of their own, fed inter-state conflicts that sometimes played themselves out on Irish shores.

From the fifth to the seventeenth centuries much of Gaelic power, built around the O’Connell and O’Neill clans, was concentrated in the north and west of Ireland. Tyrconnell, to all intents and purposes an independent medieval state, embraced parts of contemporary Connaught and Ulster and its capital, Din na NGall, was to lend its name to County Donegal. By the late 1500s, clan chieftains were actively resisting English encroachment and, by the turn of the century, looking to Catholic allies abroad to assist them in their struggles. The turning point came in 1601, when a combined Irish‒Spanish force under Rory O’Donnell and Hugh O’Neill was defeated by the English in the far south of the country at the Battle of Kinsale. After further, unsuccessful, attempts at resistance the remnants of the indigenous Gaelic aristocracy decided to go into exile from where new attempts at liberation would be launched. In 1607, the ‘Flight of the Earls’ saw the O’Donnells and O’Neills and scores of their Gaelic-Ulster allies board a French ship at Rathmullen on the Swilly.4

While the rest of Ireland survived Tudor times reasonably well, problems deepened under the Stuarts, who used settler plantations in Ulster to boost the Protestant presence in the province closest to England. But the seeds of truly enduring hatred were scattered more widely after the English civil wars and the execution of Charles I, in 1649. Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland and the bloody clockwise coastal sweep of English troops, all the way from Drogheda to Limerick, heralded widespread dispossession of Catholic landowners and set the stage for full-scale Protestant domination under the Anglican Church of Ireland’s sibling, the Church of England. The subjugation of old Gaelic Ireland came to full fruition in 1691, when the forces of Catholic James II of England were defeated by the Protestant Prince William of Orange.5

For the next 30 years, and for the better part of a century thereafter, Irish Catholics were subjected to acute economic, political, religious and social discrimination. In practice, severe restrictions on public worship eased after 1720, but Catholics had to wait until 1793 before they could vote and well into the nineteenth century before they were legally entitled to operate schools. Along with all those of other religious persuasions, they were forced to pay tithes to the established but deeply resented Church of Ireland. Those loyal to Pope and Rome rather than King and country also had to forego the opportunity of becoming officers in the army or the navy, or of becoming lawyers. Legalised discrimination of that sort became increasingly difficult to sustain both ideologically and in practice during the latter half of the eighteenth century. The American War of Independence and French Revolution rekindled Irish discontent and, to differing degrees, and in various quarters, fanned the desire for an independent united Ireland. The 1790s saw the formation of the ‘United Irishmen’ and, with the active help of the French, two failed attempts at rebellion. Britain responded, in 1801, with the hated Act of Union, enforcing a marriage between Ireland and the United Kingdom.

Seen from across the plains of time-past, the vicissitudes of churches, monarchs and states often have limited bearing on the everyday lives or well-being of the faithful, of citizens or subjects. This was perhaps even more true in a place where most of the adults, long deprived of proper education, remained mired in their own myths about fairies, powerful legends, religious mysticism and rank superstition. Ireland, however, was always too close to England and too small in scale for it not to be affected by such changes. For Ulster, Donegal, Inishowen and their inhabitants these developments were proximate and profound in equal measure, and for none more so than Jack’s grandparents. Born around the advent of the nineteenth century, at about the time of the binding Act of Union, George and Hester McLoughlin were raised amidst fears of domestic or imported revolution, social trauma occasioned by the Napoleonic Wars and the hand of a state that had dispensed with the need for a velvet glove.

History as well as the hour helped shape Irish men and women for whom the issues of politics and religion were inextricably interwoven into protective veils of confidentiality and silence. Bitter experience gave succour to males who, denied the franchise, legal standing and personal dignity that often underpinned patriarchal domestic regimes elsewhere, actively encouraged visible acts of bravado, a cult of masculinity and the excessive consumption of alcohol in public or private.6 Dispossessed of what they considered to be their natural birthright and cowed by foreign landlords who enjoyed privileged access to the state and its law-enforcement agencies, vulnerable tenant farmers and agricultural labourers employed quasi-religious oaths to bind themselves into secret societies capable of perpetrating ‘agrarian outrages’ that could be as cruel as they were cunning.7 Jack’s father, William, filled with tales of old Erin, had not only heard of many such things from his father, George, but witnessed a fair number of them for himself whilst still at Lower Fahan.8

The McLoughlin family were no strangers to clandestine organised Catholicism. At Upper Fahan, William and his brothers, James and Peter, often played in the ruins of the Abbey of St Mura, which dated back to the sixth century. Their sept had also produced several priests who, like others, had received an excellent education and training in France, Belgium or Spain. Indeed, one was a noted temperance advocate while another, only 10 miles away, eventually became the Bishop of Derry. But that was later, not many years before the Great Famine of 1845–52.

At the turn of the century, around Shandrim, most still spoke of how at the height of the persecution the faithful would have to sneak off to a sea cave on the Swilly where services were conducted in great secrecy by an O’Hegerty who was betrayed by his brother-in-law and then beheaded by soldiers based at Buncrana.9 In Inishowen, where youngsters from religious families were still being taught in illegal ‘hedge schools’ in the early nineteenth century, Catholics were slow to emerge into the full light of public worship.10 The community at Lower Fahan was formally reorganised in 1817 but it was not until 1833, when William was 10 years old, that a chapel was built that could accommodate them and the believers of Upper Fahan in a parish where those bearing the names McLoughlin, Doherty and Hegerty still easily outnumbered all others.11

But the loughs – while offering convenient conduits for travel around the ‘island’ and easy access to pathways leading to hundreds of places of concealment inland – also helped ensure that the peninsula never became fully captive to the religious-nationalist ideologies of the priests.12 Most tenant farmers trying to make a living, pay rent and find solutions to everyday problems, had little time for priestly pontification. Others, sensing that the holy fathers were hostile to secret societies and the questionable ways in which those bound to the land supplemented their meagre incomes, kept them at arm’s length. Yet others, who noticed that some men of the cloth were not beyond the temptations of alcohol or over-familiarity with the local women, became manifestly anti-clerical.13 For those in the ranks of the disillusioned or hesitant, there were often alternative sources of inspiration which, although seldom free of religious undertones, came across as more relevant and secular.

In 1796, the exiled founder of the United Irishmen, a young Protestant lawyer and Ulsterman from Belfast, Wolfe Tone, led the first of two attempts at fomenting revolt in Ireland. The first invasion, in the far south, had to be abandoned when a fleet of 40 French ships ran into bad weather. Just two years later, in 1798, and after a rebellion in the south-east of the country had been quashed, Tone launched yet another initiative when he led a second French fleet north, to the mouth of Lough Swilly. But, forewarned by spies, a far more formidable British force defeated the would-be invaders and Tone, taken prisoner, was bustled ashore at Buncrana. From there he was escorted to the castle at Dublin where he was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. He chose, however, to slit his throat before he could be executed, thereby providing Ireland with one of the earliest of its secular saints.14

Two decades later some of Inishowen’s anger was channelled into Daniel O’Connell’s countrywide movement for political emancipation, which, when it triumphed in 1829, gave Catholics access to all military ranks and, as importantly, allowed them to serve in the parliament of Westminster. But for the small number of truly militant nationalists on the peninsula, those keen to see the momentum of O’Connell’s success taken forward, the next moment of real significance came only after his campaign to have the Act of Union repealed in the early 1840s had already collapsed. Leaders of the newly founded ‘Young Ireland’, such as Thomas D’Arcy McGee, extended the concept of resistance to embrace violence where necessary, thereby laying the foundations for the ever more radical nationalists who followed. When McGee was forced to flee the country amidst the failed uprising of 1848, he was given refuge in a farmhouse at Culdaff, on the north-east coast of the ‘island’, before slipping aboard a ship for a noteworthy exile in Canada.15

But, as with many others farming around the Scalp, very few of these developments captured the interest of George or Hester McLoughlin and their sons sufficiently strongly for them to register permanently in family lore. Small-scale farmers often had good reason for eschewing conventional politics. At a time when many tenants were expected to turn out and provide a block of votes for landlord-candidates, elections were frequently of limited appeal. Nor was it much of an inducement that those living at Shandrim were forced to pay the tithes that underwrote the living of the Rector of Upper Fahan. The presence of the garrison at nearby Buncrana offered a permanent reminder of an armed British presence, and the small community’s proximity to triumphantly Protestant Londonderry, only a cart-ride away, may also have done something to limit the appeal of formal politics. Along with the rest of Inishowen, however, there may have been other reasons – more deep-seated and less visible – for the relative indifference of the inhabitants.

For all its much-vaunted greenery, most of Ireland lacked the fertile soils capable of underwriting commercial agriculture on a large scale. True, there were parts of Donegal – like the grain-rich Laggan to the south, and, to a much lesser extent, small patches in the Rosses in the far west – that could hold their own with the best in the country, but most of the larger landlords, such as the Duke of Abercorn, tended to make up with quantity what they lacked in quality. In the late eighteenth century, however, animal husbandry slowly made way for the potato and more widespread tillage. Comparatively high-yielding and nutritious, potatoes underwrote both a growing number of subsistence farmers and a notable increase in population. In the small but richer coastal strips of Inishowen a good number of tenant farmers, like the McLoughlins, also had easy access to barley, corn and oats and their diets were sometimes supplemented by fresh cod, haddock, mussels and oysters drawn from the loughs.16

In addition to that, small farmers in Ulster benefited by custom, if not by law, from ‘rights’ denied counterparts elsewhere in the country. Thus, while the vast majority of Irish tenant-farmers remained vulnerable to the predations of large landlords when it came to the ‘Three Fs’ – fair rent, fixity of tenure and freedom to sell an interest in a holding – that the Tenant League campaigned for in mid-century, those of Donegal remained comparatively secure in their tenure. Nevertheless, even in Inishowen these ‘rights’ remained in the gift of the landlord, and secret associations and agrarian societies such as the Fenians, Ribbonmen and Whiteboys were hardly unknown on the peninsula. Relative prosperity, some of it a by-product of the Industrial Revolution on both sides of the Irish Sea, partly offset the drop in agricultural prices after the Napoleonic Wars even if it failed to eliminate fully the appeal of clandestine politics.17

Conditions below the Scalp offered but a variation on these themes. Thin soils meant that, if Shandrim was to support its 2 000 or so inhabitants, it had to be larger than most other viable farming entities. Whereas most ‘townlands’ (the smaller units of land that had, since medieval times, collectively comprised a parish) averaged about 600 acres, Shandrim spread over some 1 300 acres. At double the average size of most of the adjacent townlands, it formed by far the largest part of Lower Fahan. A little grain and potato production on the lower slopes was supplemented by the sheep that searched out grazing higher up the hillside. ‘Mixed farming’, even on a modest scale, limited the excessive dependence on potatoes developing elsewhere in Ireland in the early nineteenth century. A more balanced diet may have contributed its share to Inishowen, Lower Fahan and, ultimately, the McLoughlin family’s ability to survive the worst of the devastation of the mid-century famine.18

Buncrana, rather surprisingly, was Donegal’s second largest town even though its inhabitants, too, only numbered about 2 000 before the Great Famine prompted mass emigration, leaving it with little more than 700 souls. Before that the townsfolk, the constabulary, the coastguard and the garrison all helped make it an important outlet for the produce of tenant farmers up and down the Swilly. By the 1840s, however, even Buncrana was benefiting from the rising tide of industrialisation lapping along the shores of northern Ireland; it was becoming more than a mere market town. Attracted by the quality of locally produced flax, the well-off Richardson family of Belfast erected ‘extensive mills and factories for spinning of and weaving fine and coarse linens’ that employed a ‘great number of hands’.19 William McLoughlin, like the woman from Belfast who was later to become his wife, may have had his first experience of factory work even before he left Lower Fahan.

* * *

William also knew – it was impossible for any man, young or old, not to know – of another, informal, side to employment in Inishowen, and a largely hidden social life. For all its public prosperity, based seemingly on agriculture, fishing, flax and the like, the presence of the constabulary and garrison at Buncrana spoke of another, illegal and almost totally invisible part of the peninsula’s economy that required the enforcement of the law and, when necessary, its backing by a strong military force. It was this ‘hidden economy’ that not only underwrote the otherwise inexplicable material well-being of many of the inhabitants who lived in the more remote central and northern parts of the peninsula, but also further deepened an already secretive sub-culture born of persecution.

‘The distillation of Inishowen whiskey,’ Michael Harkin wrote in his historical survey in 1867, ‘has been carried on from time immemorial.’ No matter what the season, he noted, ‘hordes of adventurous chemists are daily engaged in the preparation of this article in their highland huts and mountain caverns.’20 The illicit production of spirits from grain or potatoes – poteen – may indeed have stretched back into the dank mists of Irish time as Harkin suggested, but it seems reasonable to suggest that it may have received a fillip with the arrival of significant numbers of Scots in Ulster, including Donegal, in the seventeenth century.21

In those northern parts, spirits were the long-time drink of choice across the class spectrum. The consumption of relatively expensive beer was left largely to workers in the industrialising cities of the east and south, while wine-drinking was confined almost exclusively to the gentry. The production and consumption of whiskey in Ulster increased throughout the eighteenth century as subsistence farming underwrote a rapidly growing population. The state, keen to benefit from growth in the trade during the revenue-sapping revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, increased the duty on spirits from 10 to 14 pence a gallon in 1775. But revenue commissioners found that poor equipment and unreliable personnel militated against the full collection of dues; in 1779 they embarked on what they thought would be a minor reform and switched their focus to the taxation of registered stills. The consequences were disastrous.22

When the new act came into force the following year, it heralded an explosion in the number of illegal stills and opened the floodgates for the production of poteen and its consumption in scores of covert shebeen houses. At least some of this spirit was of such good quality that it traded not only up and down the loughs and into the very heart of Londonderry, but also back across the Irish Sea into Scotland itself. Most of it, however, was cheaper and manufactured to undercut the legal but far more expensive ‘parliament whiskey’. The resulting trade in illicit spirits, strongest in the north and west of the country between 1780 and 1850, was rooted strongly in Donegal, and especially in the most inaccessible parts of Inishowen. At first, excise men were empowered to call upon the military at Buncrana to help track down the peninsula’s illicit producers, but after 1832, their efforts were supplanted by the Revenue Police.

A developing hatred of the excise men was compounded when, in those cases where the precise source of poteen could not be properly traced, a collective fine was imposed on the entire townland, thereby further impoverishing already hard-pressed tenant farmers. Many distillers responded by posting scouts who employed elaborate alarm systems to forewarn producers of the approach of the revenue commissioners. In 1810, the Inspector-General of Excise for Donegal and Tyrone estimated that there were 700 illicit distilleries in Inishowen, and in 1814, of the 3 500 fines levied for illicit distillation throughout Ireland, some 13 per cent fell to the patch between the loughs.23

It was during this period, from 1815 through to the early 1820s, around the time of William McLoughlin’s birth, that the battle between the revenue commissioners and many – if not most – of Inishowen’s 50 000 inhabitants was at its most pronounced. Given the isolated, clandestine nature of illicit rural distillation, there were few instances of outright violent confrontation between the opposing forces. But, at the height of the struggle excise men engaged in what sometimes took on the appearance of a civil war. Denied full co-operation by landlords and Magistrates locked into complex struggles of their own with resentful tenant farmers, revenue commissioners were forced to resort to the use of informers and spies to gather the intelligence that informed military raids.

The use of secret agents drawn from within the ranks of the community only deepened mistrust and exacerbated the need for closer-knit or kinship-based conspiracies in what was already a divided society. In Ireland, the preparatory work for the more extensive utilisation of informers was undertaken in the heart of the countryside long before it was employed to cope with Fenians and other radical nationalists in the cities. In 1859, Karl Marx, noting the latter development, wrote that: ‘At this very moment, John Bull, while giving vent to his virtuous indignation against Bonaparte’s spy system at Paris, is himself introducing it at Dublin.’24 In Inishowen, a special hatred of excise men and the revenue police and their collaborators saw the murder of at least one informer.25

Soon after the passing of the act of 1789, and despite their proximity to the garrison at Buncrana, Upper and Lower Fahan were briefly notorious as small-scale centres for the production and consumption of home-distilled whiskey. It was, however, but a brief interlude. The emerging black economy attracted the attention of a particularly powerful enemy in the form of the son of the Protestant Bishop of Derry. Spenser Knox and his ally, Peter Maxwell, spearheaded a drive against illicit distillers that culminated in the wholesale confiscation of livestock when a communal fine could not be paid in cash. This not only dealt a near-fatal blow to the industry in southern Inishowen but also, no doubt, further fuelled anti-clericalism and hatred of the established church amongst distillers.26

While the production, distribution and consumption of illicit whiskey dominated subterranean social life in central and north-eastern Inishowen for the better part of half a century, from about 1780 to 1840, it was never the sole component of the black economy. Other illegalities – like poaching salmon, deer or livestock – clearly pre-dated the excise troubles and were but part of the timeless struggle between landlords and tenants everywhere. In similar vein, a little casual rural prostitution, dating back to at least the mid-eighteenth century, could be traced back to more deeply rooted poverty, but would have been boosted by the appearance of shebeens or the licensed liquor outlets to be found around the mills of Buncrana and the shirt factories at Carndonagh.27

In general, however, the excise acts – both before and most certainly after 1780 – encouraged inward- and outward-bound smuggling of alcohol in a peninsula blessed with an extensive and ragged coastline. French brandy and good quality wine found ready outlets in the residences of the rural gentry or the homes of those with more regular incomes in places like Londonderry. Illicitly produced ‘Inishowen’, much-prized by whiskey-loving Scots, was openly traded for barley off the north-east coast of the ‘island’.28 But smugglers, the trade in poteen, and the slow spread of the cash economy across Inishowen somehow also managed to draw in small numbers of other antisocial or marginal elements. The supposedly amiable ‘Black Thief’ – perhaps a ‘social bandit’ of sorts – was a sufficiently permanent feature for the village of Gaddydaff, 10 miles north of Buncrana, to be named after him. But there were also others operating on the peninsula who were sufficiently menacing for them to be termed ‘bandits’, ‘desperadoes’ or ‘outlaws’.29

Like most of the cohort that came of age just as Inishowen’s hidden economy approached its pre-famine peak, William McLoughlin and his siblings were raised in an environment that abounded with real and romanticised tales about the virtues of cunning, manliness and violence. Later in life, in a different setting, he consciously or unconsciously imparted similar values to his male offspring. But while all young men were expected to be able to look after themselves when necessary, not all such aggression could be laid at the door of the ubiquitous poteen economy; its roots lay much deeper in Irish society.

As in many rural societies, brute strength, stamina and the ability to wield fists, hands, tools or weapons to good effect were qualities widely admired in the Irish countryside. The celebration or consolation that came with the drinking of ‘parliament whiskey’ or poteen in public houses and shebeens after market day successes or failures often made for bloody brawls and vicious street fights. But while drunken clashes were remarkable for their ferocity and spontaneity, what was more striking still was the propensity of the Irish for large-scale, pre-planned, organised confrontations when questions of courage, honour or pride were at stake. Authorities and participants alike often approved and even encouraged the settling of scores between clans, family members or the inhabitants of neighbouring villages – scores that centred on perceived political, religious or social differences. Ritualised conflict saw massed ranks – not excluding women in supporting roles – engaging in faction- and/or stick-fights that formed a prominent feature of life in a precarious agricultural economy.30

As with the secret societies, some of the most dramatic and widespread instances of such collective, organised rural violence took place during periods of marked economic recession in the latter half of the nineteenth century.31 And, while probably more prominent in the south and west of the country, where they could be seen as distant spasms of rural poverty attributable in part to accelerating industrialisation across the Irish Sea, such occurrences were not entirely unknown in Donegal or the neighbouring counties.32 Nor, for that matter, was there a dearth of examples of ritualised interpersonal violence in or around Inishowen itself in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. ‘The popular Sir William Richardson of Augher Castle, County Tyrone, devised a system of trial by combat: sturdy disputants who appealed to him in his magisterial capacity were armed with cudgels and dispatched to the back of the backyard of the castle to fight it out.’33 In similar vein it might be noted that the last formal duel with fatal consequences to be fought in Ireland took place, in 1810, at the old Druminderry Bridge near Buncrana.34

* * *

Uniforms, codes of honour and dangerous intruders were not always the ‘island’ community’s most troubling enemies. Given the number of visible challenges that confronted men and women on the land in Donegal and elsewhere in Ireland by the mid-nineteenth century, it was perhaps ironic that the nemesis of most should – sometimes quite literally – have floated in unseen on summer breezes. Microscopic spores, released upon the wind from the contaminated holds of ships, drifted inland to spread the potato blight, or were unwittingly carried into markets in the form of already infected tubers. In the fields the leaves of the plant turned brown before the tubers upon which nearly a third of the population directly depended inevitably succumbed to rot and crumbled into nothing.

What precisely happened in Lower Fahan, or even within the extended McLoughlin family, was never considered worthy of separate public, or private, recording. For one, the failure of the potato crop in Donegal was not without precedent – it had happened to lesser degrees in 1816–19, 1821–22 and then again in 1830–31. A slight shift away from potato farming to livestock even before the Great Famine may have protected some of the county’s inhabitants. It so happened that the coastal resorts of Inishowen, including those around Inch Island, attracted growing numbers of summer visitors throughout the period 1840–50. The price of grain, dairy and poultry all held up well in the local markets and, even at the height of the famine, farmers were still sending produce to Derry. And perhaps crucially, access to fish and other seafoods via the jagged coastline and loughs meant that Donegal never experienced the catastrophic hunger experienced in the poorest western counties.35

Amidst the mild and moist conditions in which the blight thrived, the harvest of 1845–46 slumped by 50 per cent. But it was ‘Black 47’ and the equally bad year that followed, in 1848, that sealed the fate of many Irish men and women, if not those clinging to the fringe of the Scalp. By 1852, a million people had succumbed to hunger and, by the time that the complex readjustments to the rural economy that gave rise to the Land Wars of 1879–1882 were done, Ireland had lost 20 per cent of its population to death or emigration to Atlantic or Pacific destinations – America, Canada and England, or distant Australia and New Zealand.36

When the Griffiths land valuations were conducted in the 1850s, it was recorded that George, and perhaps Hester, McLoughlin were still to be found at Shandrim. Rural economies recognised and valued men and property rights more readily than women and family members. By then, however, ‘Black 47’ had long since prised their 20-something-year-old son William and two of his brothers off the thin soil of Lower Fahan.

At some point in the late 1840s, William McLoughlin joined the exodus to the coast where ships from Inishowen had for several decades been loading the butter, fish, fowl and other livestock that made its way to Glasgow or Liverpool where it fed the gathering mass of urbanised men and women labouring just across the Irish Sea.37 There had been a time, not long past, when the Industrial Revolution had been content only to consume Ireland’s agricultural products and the labour of young migrant agricultural workers at the peak of their physical powers – the spalpeen. But the factory-beast across the water now wanted more; much more. The mills and their congested surroundings were devouring the bodies, minds and labour of men, women and small children alike.

Like thousands of others forced to set sail amidst the gales of poverty, William McLoughlin left Ireland with nothing, or very little, to show by way of cash or material goods. But as empty as were his pockets, so full was his mind with attitudes, concepts and half-formed ideas derived from time spent on the Scalp and in Inishowen. A world view nurtured in the countryside and shaped to fit the pace and needs of a venerable rural economy was about to be transplanted to a modern city and an industrialising society that was without historical precedent.

The ghosts of parental culture and socialisation chase after each successive generation of humanity. Their ability to induce courage or fear, to inspire or defeat, may wax and wane with the time and place, but traces – sometimes the faintest of hints – remain; they are always there, they help make us who we are. Grandfathers shape fathers just as surely as fathers shape sons as the cycle endlessly repeats itself. Like the genetic markers of diet and disease, however, the imprimatur of male influence need not always play itself out directly or proportionately among immediate successors. Habits, traits and values can lie dormant for a generation or two and then, long forgotten, re-manifest themselves where and when they are least expected. But it is also true that sometimes the heavy hand of the phantom grandfather or father can readily be detected on the shoulder of the most recent of the offspring.