CHAPTER ELEVEN

Metamorphosis

TO POTCHEFSTROOM AND BACK

— 1890 —

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

As to the thief, male or female, cut off his hands: a retribution for their deeds, and exemplary punishment from Allah, and Allah is exalted in Power, Full of Wisdom.

Prior to the Ancoats pawnshop break-ins in 1878, at age 19, Jack McLoughlin had only a minor criminal record. Then he served a year in prison, in London, for a street robbery that went wrong. But, after that, he avoided arrest for deserting from the navy and led a charmed life on the run in Australia before fleeing to Natal. There is no surviving record of his having been in trouble with the law while at the College of Banditry, or in Mozambique. His only setback in southern Africa came at Barberton, where he served six months for the Eureka City invasions. It all pointed to a certain amount of professionalism on his part and the limitations of stretched colonial police forces on the other.

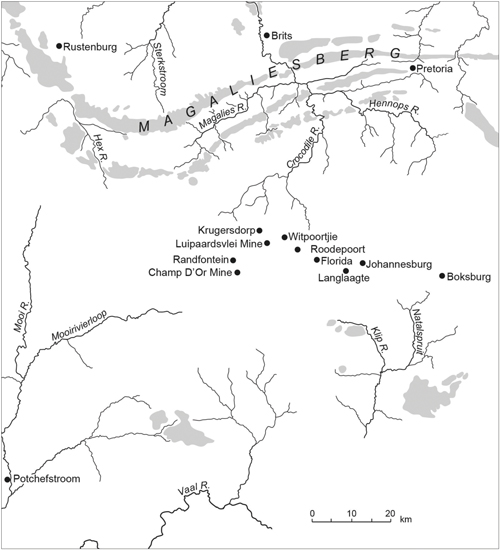

The West Witwatersrand and its Hinterland, c 1895

The same serendipitous combination of cunning and official ineptitude characterised the first 24 months of his stay in Johannesburg, between 1888 and 1890. In the absence of any archival evidence, perhaps the best way of reconstructing what he may have been up to during those two years is to take a peek at the underworld activities of a few of his closest accomplices. Jack McCann – whom he first met in Singapore and then befriended in Pietermaritzburg – is easiest to trace.

In March 1888, a month after the Irish Brigade descended on Johannesburg like a biblical plague, McCann became a part-time barman at Connolly’s Sportsman’s Arms. A few weeks later he was convicted of the theft of a revolver and spent some time in prison. By the time that he was released, in July, one of the most advanced mining operations on the Rand, which had progressed well beyond open-cast diggings, was already in trouble. The Croesus was part of a group of mines belonging to George Goch and battling to recover gold from pyritic ores. The manager, confronted by a chemical impasse, was forced into crisis mode. His entire stock of quicksilver, stored in huge 70-pound canisters – each containing £10-worth of unrecovered gold – was locked-down in an abandoned battery house.1

In August, Harry Fisher, a part-time miner and gang confidant who had been ‘working’ at the Croesus during the shut-down, told McCann about the store of mercury-amalgam. McCann decided to steal a few of the canisters, and with the help of Fisher, another ‘miner’, Charles Hartley, and a cab driver named Miller, set up a scheme to sell the canisters to an unnamed Jewish contact who would recover the gold. The battery house was broken into on the night of 11 September and eight casks of quicksilver-gold removed. But, thereafter, things quickly turned sour.

Fisher failed to make the rendezvous at the mine on the night of the break-in, leaving McCann and Miller to lug the heavy canisters to a waiting two-wheeled scotch-cart. The following morning, McCann, who had linked up with Hartley, learned that their Jewish collaborator had backed out of the deal. It necessitated a change of plan. The canisters were moved into rooms at the back of the Brighton Hotel. The Brighton was a dive, replete with ‘actresses’ doubling as ‘barmaids’ and other friendly females. But the proprietor was the most successful illicit gold dealer on the Rand in the early to late 1890s, George Mignonette.2

Mignonette’s real name was George Ackland. Despite being at the centre of amalgam theft in Johannesburg for a decade or more, he was never successfully prosecuted, even when – in 1898 – he was the subject of a sophisticated secret-service type operation mounted by Kruger’s reforming State Attorney, JC Smuts.3 Mignonette may have been a Catholic and had once been based in France but, other than that, little is known about him. Prior to his arrival on the Witwatersrand, he may have been on the Kimberley diamond fields where he may have met McCann, who, after deserting the army, had worked there briefly as a winding-engine driver. Part of Mignonette’s mid-career success was attributable to the fact that, by 1893, he was in league with Johannesburg’s corrupt Chief Detective, Robert Ferguson. Ferguson, too, was picked up in an undercover operation against gold dealers launched by Smuts in 1898.

But, at the time of the Croesus break-in, the Chief Detective was in the earliest stages of constructing his own network of illicit gold dealers and poorly disposed towards potential underworld rivals. Ferguson spent most of his time in public houses and relied on informants to provide him with a reasonable flow of arrests and convictions. Despite this public persona, Ferguson was understandably secretive about his private life and managed to conceal his corruption well into the 1890s. He may also have been assisted in his own undercover operations by his wife, who – as one of Smuts’s secret agents claimed – was an ‘off coloured woman’.4

Ferguson had more reason than most to know that the use of informers, or guaranteeing underworld associates freedom from prosecution in exchange for giving evidence, were practices deeply abhorrent to most Irishmen. If he did not know, then anyone in Johannesburg could have told him about James Carey. Carey was one of the ‘Invincibles’, a radical off-shoot of the Fenians who had assassinated the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and his Permanent Undersecretary, Thomas Burke, in Phoenix Park, Dublin, in 1882. In return for turning Queen’s evidence, the British had provided Carey with an assumed name and put him aboard the Melrose Castle to take on a new life in Natal. But, just off Port Elizabeth, Carey was recognised by a Donegal man, Patrick O’Donnell, and shot as a traitor to the Irish cause.5

It is not known who provided Ferguson with his initial lead in the Croesus Mine case, but, acting on information received, he visited the mine and got the manager to check that his store of mercury-amalgam was intact.6 It was not. Eight canisters were missing and Ferguson arrested McCann, Fisher, Hartley and Mignonette on a charge of ‘receiving and dealing in stolen amalgam and quicksilver’. It was one of very few successes the Chief Detective enjoyed during a long term of office that coincided with a remarkable increase in gold recovery as a result of the MacArthur-Forrest process. By 1893, losses of amalgam were becoming so serious that the Chamber of Mines pressed the government to introduce draconian legislation to deal with the mounting problem.

By the time the preliminary examination for the Croesus case took place, on 11 September, the Chief Detective was encouraging Hartley to turn informer.7 Hartley co-operated and Ferguson, for reasons known only to him, worked up the case in a way that left the Public Prosecutor inclined to pursue only McCann. Fisher and Mignonette were suddenly released and given the time and space in which to reorganise themselves in ways that seem to have kept their earlier relationship with McCann intact. For unknown reasons neither McCann nor his close friend, Jack McLoughlin, were inclined to deal with Hartley in ways the Irish often reserved for police informers.

In October, whilst awaiting trial, McCann escaped by digging his way through a prison wall and teaming up with Jack Burns, another shadowy underworld figure from Ancoats. The two then set course for Delagoa Bay and the freedom of the Indian Ocean world. In Steynsdorp, the pair stole some horses and crossed into Mozambique where, given the absence of an extradition treaty, the policemen tailing them were unable to effect an arrest. Marooned in Lourenço Marques without the funds to get to Australia, McCann changed his name to ‘John Boswell’ and boarded a steamer for Natal. In Durban, he was recognised while watching a cricket match and arrested as a fugitive from justice. After a few exchanges between Pretoria and Pietermaritzburg he was escorted to Johannesburg and made to stand trial for the theft of mercury. Neither his escape from prison, nor the theft of a horse, attracted further attention.8

McCann’s trial, in the Johannesburg Circuit Court in mid-July 1889, was marked by shenanigans of the sort that became common as matters pertaining to gold theft, the detective department and the Public Prosecutor’s office combined to yield what approximated to ‘justice’. Somebody, probably George Mignonette, retained an advocate to defend McCann in a way that avoided any hint of police corruption and failed to disclose the major network profiting from amalgam theft. When McCann realised that he was being prevented from calling witnesses for his defence, he insisted on the advocate withdrawing. But by then, even though Hartley had not risked giving evidence in court, the damage had been done. Judge Esselen found McCann guilty and sentenced him to two years’ imprisonment with hard labour, notwithstanding a later petition for a reduction in sentence based on the fact that his left arm was said to be somewhat shorter than his right.9

As a serious offender likely to attempt to escape, McCann was sent to Barberton to serve out his sentence under the sympathetic eye of the chief gaoler and fellow Irishman, Thomas Menton. Menton ensured that McCann was restricted to light duties only and, a little more than a year later, supported his plea for remission of sentence. But Kruger’s Executive Committee – the cabinet – denied the request and McCann was eventually only released in February 1891.10 In effect, his incarceration denied McLoughlin access to his closest and most trusted lieutenant during the worst of the depression.

McCann was not the only loss. William Kelly, ex-Fort Napier and ex-Barberton, had talked his way into the position of manager of the small Royal Gold Mining Company shortly after the Irish Brigade entered Johannesburg. He was soon friends with the influential Victor ‘Chinaman’ Wolff, a speculator and confidant of Ferguson’s, who, a few years later, was found guilty of perjury in a famous libel case which the magnate JB Robinson brought against the author Louis Cohen.11 Kelly lost his position when the gold-recovery crisis set in, but then returned to the mine and stole six cases of dynamite. He may have been the principal dynamite supplier for the McLoughlin gang’s earliest safe-blasting exploits in central Johannesburg. Caught and charged, however, in January 1892 Kelly was sentenced to four years’ hard labour for the theft of the dynamite.12

The prolonged absence of McCann and Kelly did nothing to restrict the safe-cracking exploits of the McLoughlin gang before, or after, the 1889–92 depression. Prison-time was an occupational hazard and the composition of the gang mutated constantly to accommodate a need for specialist skills and raw muscle-power, and the nature and value of any potential loot. There was also a steady inflow of Manchester-Irish from which to recruit – or, if all else failed, even more English underworld elements hailing from the industrial cities of the north-east or north-west.

The gang’s modus operandi, although varying in detail, was developed during those earliest months of the frontier era. Its pioneering operations came at a time when smaller open-cast diggings did not make for a significant build-up of gold amalgam on site. So, instead of concentrating on the emerging mines, the gang focused on the premises of successful retailers and wholesalers in the unlit streets around the Market Square. The template they developed there was later adapted, extended and used at isolated mine offices once the deeper-level mines got the MacArthur-Forrest process to yield larger quantities of gold. At deep-level mines, the gold amalgam stored in free-standing safes and cheaply constructed offices before being transported to the banks or moved to a central refining facility proved to be a relatively easy target.

Once a promising retailer or wholesaler’s premises had been identified, between three and a dozen men determined when the week’s cash-holdings were likely to be at a peak and then waited for the right weather conditions to set in. Moonless, heavily overcast summer or cold and wet winter nights that muted sound and kept people indoors were best suited to the removal and blasting of large safes. Sounds emanating from the nearby mines, as battery-stamps gnashed their way through mountains of rock, helped mask the sound of any explosion but, as already noted, it was the summer thunderstorms that were the safe-crackers’ best friend of all. Arcs of lightning and heaven-rending thunder combined to provide optimal conditions of light and sound.

The operation was run on quasi-military lines, in ways a British Army officer might approve of. A detail of two to four muscular thugs would be deployed to fan out, occupy strategic corners and act as sentries. The main party’s flanks and rear were thus protected from the unwanted attention of passers-by or policemen on the beat. A smaller party of experienced burglars would then use ‘false keys’ to gain easy and silent entry to the premises – or, failing that, force the latches and locks on doors or windows.

If for some reason a very heavy safe had to be blown on site, the experts would move into position. These were men who knew about metals and metal-working, detonators and dynamite. But because on-site blasting increased risk unnecessarily, safes were often removed. In such cases a much larger group of men would use ropes to manhandle the safe onto mats or blankets. The safe would be lugged out and placed on a barrow, cart or wagon and transported to the outskirts of the town, or a nearby mining property. There, under the cover of the storm, within earshot of other explosions or the rumble of thunder, the door would be blown, the loot shared and the robbers rapidly dispersed.13

After July 1889, as the diggings faltered and gold became harder to come by, the largest safe-lifting, robbing and blasting projects all took place in the town centre. Dunton Brothers, the International Wine & Spirit Company, Payne & Trull and the Permanent Mutual Building & Investment Company were among the businesses that had safes removed or blown during this period. With the exception of the botched job at Dunton Brothers, which saw the conviction of two Irishmen – Cahill and Michell – Ferguson was unable to arrest, let alone prosecute any suspects.14 These were notable police failures because most of the projects during this period were undertaken by a few of the less experienced stragglers from the old Irish Brigade. By then, many of the ‘hard men’ had abandoned the town in a search for greener pastures.

By February 1890, many diggers, mechanics, prospectors and unskilled whites, sensing another sad Barberton in the making, were clambering aboard mule carts and heading south towards the diamond fields of Griqualand West.15 A good number of professional criminals, being less pessimistic and not beholden to anyone, lingered on through the late summer. But when winter set in even they had second thoughts and retreated. In early May, readers of the Diamond Fields Advertiser in Kimberley were warned that they should brace themselves for a large influx of ‘loafers’ as well as a smaller number of dangerous characters.16

Unlike most unemployed whites, the core of the old Irish Brigade had acquired some experience of rural and small-town life while moving through the eastern parts of southern Africa and were in no hurry to get to Griqualand West. As former highwaymen they were well aware that prosperous Boer farming communities adjacent to the Witwatersrand had provided the diggings with firewood, meat, fruit and vegetables during the good times. Potchefstroom, Rustenburg, Klerksdorp and Bloemhof had all evolved into modest farming centres with their own administrative, clerical, educational, retail and wholesale resources. They all had courts, government buildings, post offices and shops, but, lacking easy access to secure banks, often saw a significant build-up in cash and negotiable instruments during the intervals between the weekly coach services that connected them to the capital. As McLoughlin and friends saw it, the retreat to Kimberley or beyond could be self-financing.

* * *

During the winter and spring of 1890, a gang of 10 to 12 bandits was active in the Magaliesberg, just west of the Witwatersrand. Working in the hilly terrain favoured by insurgents, they concentrated their efforts in and around Rustenburg – a district represented in the Volksraad by State President Kruger, who owned a farm at Boekenhoutfontein. In June the mail coach between Pretoria and Rustenburg was held up and robbed of £400.17 Only weeks later, during a dark and stormy night, on 9 August, the Landdrost’s office in Rustenburg was plundered. Skeleton keys were used to gain entry and a huge safe, holding £4 000 in cash, was carried away and blown. It was estimated that it would have required a dozen men to remove the safe. The following night, a smaller group, which may have been an offshoot of the brigands, raided the Central Hotel at Roodepoort, removed and blasted the safe, but only got £100 in cash for their efforts.

Embarrassed by a series of robberies in the presidential backyard, Kruger sent two detectives to investigate, and then, in an unprecedented move, six members of the State Artillery were despatched to assist the police. The bandits dispersed, but one, Charles Brown, and two Manchester-Irish – James Sutherland and William Todd – were found carrying large sums of cash. Hermes-like, Todd was doubling-back to the Magaliesberg when he was arrested near Krugersdorp. His possessions, rolled into a blanket and strapped to his back in the style of an Australian ‘swagman’, contained coins bearing marks that might have come from an explosion.18 But it was too little, too late, and the state still had little idea of what it was up against. By then most of the brigands had moved further afield.

Among earlier arrivals in the near western Transvaal that winter was John O’Brien, the ex-Fort Napier confidence man, formerly a policeman at Barberton. Another was the ‘Australian’ James Williams, aka James William Kelly, another College of Banditry man, who by then was calling himself ‘William J Reid’.19 But, in amongst the general migration of bandits, some of whom were soon behind bars, was the new safe-cracker extraordinaire himself.

In mid-May 1890, with the gold mines in crisis, McLoughlin abandoned if not the Magaliesberg, then certainly the Witwatersrand. Happy to carry notoriously unstable dynamite around with him, he embarked on an exploratory foray, together with two accomplices, into the towns lighting the way to the diamond fields.20 Their first stop was at Rustenburg, where, working with the flow of the commercial week, they waited until late Friday afternoon, 16 May, before checking into Brink’s Hotel.

The next morning they went to the leading retailers in town, Somers & Co, to establish the lie of the land. Then, chancing their arms, they attempted to cash a cheque but a smart assistant, unconvinced by an indistinct signature, refused to help them. Undeterred, they moved through the lanes and yards behind the shops and found a sturdy, unsecured barrow. They then mapped the safest and easiest route from Somers’ store to the outskirts of the town. That done, they returned to the hotel where, in low key, they enjoyed a few Saturday evening drinks.

They arose late the next morning, having slept through the sound of early-morning worshippers making their way to church. Towards midday, as the Sunday silence descended upon the town, they made for the residents’ bar. Still on their best behaviour, they spent the afternoon talking and drinking before entering the dining room for the evening meal. Around 8.00 pm, they left the hotel and whiled away a few uncomfortable hours out in the chill, waiting for the residents to drift off into a warm winter’s sleep before going to collect the purloined barrow.21

The main door at Somers’ was forced somewhere between 11.00 pm and 2.00 am. Blankets were placed on the floor and the safe was tipped into a makeshift cradle before being hoisted into position on the barrow. Covered by blankets, it was hauled three miles out of town, where, with the sound muffled by mere distance, it was laid on its side and blasted open. Rustenburg was still snoring when the loot was divided. The three men then split up – the tracks of one or two seemingly heading east, in the general direction of the goldfields, but the others – more worryingly for the police – heading west, in the direction of the Bechuanaland border.

Monday morning saw great excitement as news of the heist spread and the extent of the loss became known. It was, even by international standards at the time, an impressive haul: £300 in cash, close on £300 of bearer scrip, promissory notes, life policies and title deeds as well as several gold and diamond rings were missing. The fact that the gang was happy to take negotiable instruments that would have to be traded through shady brokers hinted at the presence of the Irish-Australian, Williams. McLoughlin’s own preference was usually for cash, gold, jewellery and gold-chain watches.

The police made good progress tracking the suspects on their way to the Witwatersrand to within an hour of the small hills and ravines around Krugersdorp. This chimed with the idea that McLoughlin was involved because the west Rand town was known to be a favourite haunt of his. Suspicions were confirmed when they obtained descriptions of their suspects. The two were, the police admitted to journalists, ‘well known desperate characters’. ‘The one is below medium height, being about five feet four inches, dark complexioned, with a black moustache; he is stout and well built.’ It was the next best thing to a photograph – a fine word-portrait of Jack McLoughlin at the peak of his physical powers.22

But instead of facilitating enquiries that might lead to an arrest, this description – which appeared in a leading Johannesburg newspaper – merely became part of a mystery that surrounded McLoughlin for five more years. Here was a ‘desperado’, ‘well known’ to police and press alike, whom no one was willing to put a name to! Neither Ferguson nor Emmanuel Mendelssohn, Editor of the Standard & Diggers’ News, referred to him by name. Nor, for that matter, did they even mention the Irish Brigade, even though many of its members continued to frequent the town’s pubs. It all suggests that long before 1895, when McLoughlin became so notorious that not putting a name to his deeds was no longer an option, he was already considered so dangerous and so widely feared that even his most powerful adversaries were cowed into silence.

The police knew who they wished to interrogate about the Somers safe-blasting but failed to find their main man. They suddenly lost their appetite for the chase. Several days were wasted obtaining warrants for suspects who, despite the fact that the trail of two of them led to Krugersdorp, were suddenly thought to have been across the border, in Mafeking.23 Even at the time that must have seemed a touch improbable – but given what followed, it was just absurd.

McLoughlin was no shrinking violet. He exuded confidence and, when flush, spent money freely in public places. He was known for his love of gambling, and when not at the race track spent an inordinate amount of time drinking and dining with scores of admiring ‘Irish’ and other miners in predictable locations. He may, of course, have kept so low a profile that it was thought that he had ‘disappeared’ or ‘left the country’. But even that excuse must soon have worn thin. Just three weeks after the Somers job, already penniless after a bout of urban carousing and back on the country trails leading to the diamond fields, McLoughlin was arrested on an unrelated charge, operating under his own name, in a nearby town.

* * *

The Potchefstroom gaol, constructed before the Rand gold rush, housed several tough nuts sent there from Johannesburg during the depression. Others had been locked up there after having fallen foul of the law while en route to Kimberley. Among the latter was James Williams, aka WJ Kelly, aka JW Reid, who had probably been with McLoughlin in Rustenburg only a few weeks earlier. He was soon to be joined by John O’Brien of Manchester, the College of Banditry, Barberton and the Irish Brigade.

For the thousands of white tramps and vagrants negotiating southern Africa in the late nineteenth century, the local parson or priest was the first port of call when searching for a meal or money.24 But O’Brien was more of a confidence trickster than a 24-hour tramp. He set his sights higher than most tramps, using any hard luck tale that came to mind about God or the Old Country to obtain work and accommodation. In Potchefstroom he found Father Trabaud, an Oblate in the Order of Mary Immaculate, whom he must have thought of as a relatively easy touch.

Trabaud had ‘taken his obedience’ and moved to Potchefstroom in late 1889 to oversee the erection of a convent for the Sisters of the Sacred Heart. Shortly after building operations commenced, O’Brien drifted into town after a month-long binge in Johannesburg where he, JW Reid and some other unnamed Irishmen had been out on a blinder. The wily Oblate insisted that O’Brien ‘take the pledge’ to give up drinking before agreeing to take him on as a ‘servant’ and general odd-job man.

Their arrangement worked reasonably well as O’Brien settled in to ride out the depression. For six months there was no outward sign of discord between the priest and his new manservant. Then, about a month after the Rustenburg robbery, around mid-June 1890, JW Reid suddenly appeared out of nowhere. He and O’Brien resumed a friendship born of shared thirst and were soon in and out of several disreputable pubs in town. Before long, in an incident that reeked of cheap liquor, Reid was jailed for the very ‘Irish’ offence of obstructing the police in their duties.25

Reid’s removal and incarceration was God’s final concession to O’Brien; a much sterner test lay ahead. Within days McLoughlin materialised, without funds, the worse for wear and hoping to link up with Reid for the journey south. O’Brien, already struggling to stay on the straight-and-narrow, found McLoughlin impossible to deny. He asked Trabaud to help a fellow Catholic, an Irish friend who was passing through Potchefstroom and who had fallen on hard times. The Oblate, softened by hard times, relented and was soon being assisted by two ‘servants’.26

For some days all seemed well. A feeble winter sun and seasonal cold saw the town’s pulse drop to levels that threatened both the physical well-being and sanity of its inhabitants. The correspondent for the Standard & Diggers’ News was one of those driven to distraction and his judgement faltered. In the closing days of June, he reported to the Editor, in Johannesburg, that there had been a ‘robbery at the convent’, but that ‘everything here remains extremely dull’.27 If he had shaken off his lethargy and traced ‘the story behind the story’ it would not only have led him back to the safe robbery at Rustenburg but prepared him for the extraordinary sequel that played itself out over the next four weeks.

On Wednesday afternoon, 25 June 1890, without cash and facing the prospect of another cold, uncomfortable night, McLoughlin and O’Brien decided to rob the priest. As Trabaud returned to his room at dusk and unlocked his front door, he was carefully watched. When he left a minute later, for what they hoped would be a lengthy absence, McLoughlin and O’Brien slipped into his room unseen. Foregoing the role of sentry, McLoughlin sat on the bed as O’Brien rummaged through the Oblate’s possessions until he found three small boxes. One contained a few personal belongings, the second the priest’s meagre savings and the third about £20 that Trabaud had raised for a library through public subscription. McLoughlin was still sitting and O’Brien moving towards the door with the boxes when the priest walked in.

Realising what was happening, Trabaud played for time. An argument ensued and, after a brief tussle, the Oblate got back two of the boxes, but O’Brien simply refused to let go of the third. At that point, McLoughlin, who had remained seated, joined in the noisy exchange and O’Brien suddenly demanded that the priest provide them with beer. Trabaud, looking for a way out, hauled out a few bottles which they opened and then began to drink. The argument moderated as all three took stock of the position. O’Brien, still clutching the third box, knew that he was in trouble, but McLoughlin’s own position was less clear. The two were still thinking through their next move when the priest made a run for it.28

By the time that the constables got there, the birds had flown. Trabaud, however, knew where to find O’Brien. He led the police to a ‘canteen of questionable repute’ run by a Mrs van der Kemp who lived in a corrugated-iron cottage adjoining the bar. Sure enough, O’Brien was at the bar, but of McLoughlin there was no sign. At that point the constables had second thoughts and, deciding that O’Brien could not be arrested without a warrant, set off to find the Magistrate. When they returned, Mrs van der Kemp refused them entry and the canteen doors had to be forced. There was no sign of O’Brien, but the police, warming to the task, went to the cottage and when refused entry for a second time, broke down the door. Inside, oblivious to all the noise, lay McLoughlin, who, on being identified by the Oblate, was arrested and led away.

O’Brien had fled with the cash but the constables knew that it was only a matter of time before he surfaced in one or other pub. And, sure enough, just three days later, they arrested him at Simmonds’ Bar. On 20 June, he and McLoughlin appeared before the Magistrate. O’Brien, charged with robbery, was found guilty and held for sentencing. But it was a busy Monday morning, and McLoughlin’s case, in which he was charged with complicity, was postponed. The pair were escorted to the gaol, where they found Reid along with various other long-term prisoners from Johannesburg.29

The gaol was a ramshackle affair, consisting of a single block divided into four cells that were partly interleading and all unequal in size. The recession on the Rand had, it was said, turned the gaol into a ‘convict station’ overseen by an acting commanding officer with 10 men who took turns, in shifts each five-strong, to guard the prison by day and night. Two-score criminals, some graduates of the Empire’s finest prisons, had been herded into the largest cell. The situation there was so volatile that only two armed warders were allowed into the cell at a time. Forty other prisoners were held in two other cells while the smallest cell of all was reserved to hold a modest number of local civil debtors.

McLoughlin, awaiting trial, and O’Brien, yet to be sentenced, did not qualify as convicts and were placed in the debtors’ cell. One of the walls in the cell separated it from the adjacent dispensary, which had a small window overlooking the street and a door leading out into the prison yard, which was without a gate. It was not a serious challenge. McLoughlin and O’Brien told Reid, a short-term prisoner, that they were set on escaping and he persuaded the gaolers to let him move into the debtors’ cell with them. The authorities had, unwittingly, assembled a Fort Napier Irish trio.

The three inmates found a short piece of iron for excavating while out in the exercise yard, as well as an old condensed-milk tin. The lid of the tin was removed and a hole gouged out of the side. A candle end was put inside the tin and the makeshift bull’s-eye lantern yielded a small beam of light to work with by night. Saturday morning, 26 July, at a low tide in circadian rhythms, was agreed upon as the best moment for the escape.

Excavations began at around 2.00 am and after an hour’s digging, the hole through the wall and into the dispensary was large enough to crawl through. But, at about the same time, one of the Boer guards thought that he heard a scraping sound coming from the cells closest to the street and sent a black warder to confirm his suspicions before rousing the gaoler. The gaoler sent for a policeman living close by and told him take up a position that allowed him an unobstructed view of the yard outside the dispensary and the unmanned prison gate beyond. Two other duty-warders took positions beside the main block overlooking a low prison wall that gave them a clear line of fire into the street beyond.

Unaware of what was happening outside, the Irishmen eased aside a wooden table blocking their access to the dispensary and, once inside, silently dismantled the lock on the wooden door leading out into the yard. Inside, the trio were at the point of no return, but outside the gaoler was still uncertain as to where exactly the cell-block wall was about to be breached. The stalemate was broken when the dispensary door burst open and the trio charged into the yard, towards the gate and the street.

In the passageway overlooking the yard, the policeman raised his revolver, shouted four warnings that were ignored and then fired two shots. One of the men, already in the street, stumbled and fell directly opposite the gate. The other two accelerated away down the street. But the guards overlooking the prison wall had heard the gunshots in the yard and were waiting for them. They shouted out three more warnings and then fired several shots in the direction of the fugitives. There was more stumbling and then, total silence. Reid, found lying opposite the gate, had taken two bullets from the policeman. The first had penetrated a lung and the second had splintered a bone in his hip. McLoughlin was found trying to staunch blood streaming from the wrist of his right hand. O’Brien, however, was lying perfectly still: O’Brien was dead.30

The attempted escape and its sequel caused a sensation. By Monday everybody in town had heard about the shootings. Irate English-speakers, attuned to thinking the worst of the Kruger administration, saw the gaoler’s failure to enter and search the cells before deploying his men as part of a sinister Boer plot. The Landdrost, displaying great tact and understanding, co-operated with the local press, who were given access to all the guards and the prison premises in order to establish the facts of the situation. The findings placated the most agitated imperialists and the town’s ‘race relations’ were restored to a reasonable level.31

For some days official reports about the wounded men remained totally confusing and misleading. In a telegram to Pretoria, the Landdrost informed the State Secretary that O’Brien was dead and Reid seriously injured but that McLoughlin had received only a ‘superficial’ wound. But by 6 August, the full extent of the damage was becoming apparent. Reid was operated on successfully, the wounds in his chest and hip cleaned and stitched. Doctors were confident that he would recover fully.

But McLoughlin was in bad shape. The bullet had shattered his wrist and two doctors had excised the joint, leaving his right arm with a dangling appendage. The pain was excruciating, the prognosis awful. He was told that the hand was useless and that it would have to be amputated.32 Three weeks later he was still languishing in the gaol ‘hospital’ receiving, it was said, excellent treatment. Reid was released and returned to the Rand, where, as ‘Kelly’, he joined up with associates from the Australian underworld to resume an active criminal career.33

The charge of McLoughlin having been complicit in the fracas at Trabaud’s was dropped and never featured in his subsequent criminal record. There was also no further mention of it in press reports and the story failed to surface in the folklore of the Johannesburg underworld. This structured silence may partly have been engineered by McLoughlin himself. For reasons that can only be speculated on, he seems to have been humiliated by the convent robbery, the death of O’Brien and the amputation of his hand. It did not fit the image of the ‘hard man’ he had cultivated and, nearly 20 years later, he was still denying – while under oath – that the loss of his hand had anything to do with events at Potchefstroom in 1890. A Boer bullet had shattered his wrist, but it had done even greater damage to his self-perception and he never forgot it.34

The danger of infection from the initial procedure receded but the Potchefstroom doctors felt unable to perform the amputation. A new and impressive general hospital had only just opened in Johannesburg and the surgeons there were accustomed to dealing with serious trauma arising from mine accidents.35 In early summer 1890, McLoughlin was subjected to chloroform for a second time in months. The amputation was successfully performed by Dr John van Niekerk, the recently appointed ‘Resident Surgeon and Dispenser’ and a graduate of the University of Edinburgh.36 But it was not without additional personal cost.

The hand could not simply be cut away from what was left of the wrist joint: Van Niekerk was forced to remove part of the lower arm in order to ensure that the procedure was a success and, in that moment a ‘terrible beauty’ was born. McLoughlin, perhaps half-prepared to accept the loss of his preferred hand, now had a much harsher reality to face. Left without a lower forearm, in underworld circles he became known as ‘One-armed Jack’, although he was never directly addressed as such.

The agony of the amputation was not the only cause of discomfort while he was recovering in the hospital. There were other mysterious aches which, seeming real enough, could not be rationally accounted for and, over the months that followed, only became worse. The nurses, too, unsettled him. Drawn from the Order of the Holy Family, the sisters would have known about the priest-robbing and death of O’Brien via the Catholic grapevine.37 He cared little about what other men thought, but the nuns left him feeling uncomfortable: he could not easily look them in the eye.38 McLoughlin’s Catholicism ran deeper than he thought.

He left hospital physically and psychologically diminished, filled with self-pity. It had taken just six months for everything in his life to change. Some said that the bad economic times on the Witwatersrand were lifting and that a new scientific discovery would save the mines, but he could see little sign of it. Like the limbless soldiers selling matches outside Victorian railway stations in Liverpool and Manchester, or the Irish tinkers who wandered about Lancashire’s country lanes repairing kettles, he had little of real value to offer anybody. There was no chance of his finding work; even re-entry into the local underworld would be daunting.