CHAPTER TWENTY

Courting Solitude

AUCKLAND TO CHRISTCHURCH

— 1896–1900 —

Till you cage in the sky, the sparrows will fly.

Although McLoughlin’s confidence was low, he retained some of his charisma and an ability to lead. On leaving Mount Eden he joined forces with an unknown, recently discharged prisoner and within hours managed to assemble a set of house-breaking implements.1 He was convinced that his long-term interests were best served by raising the money to get himself to Australia and link up with his brother. But the problem, as before, was how to raise funds for a passage from the east coast of the North Island to Melbourne, more than 1 000 miles away. One thing was certain; he could not afford to linger in Auckland, where he was at risk of being spotted by police who would be quick to monitor the movements of a known felon.

Like betting on horses, something quite irresistible when he was in the money, he never overcame the desire to gamble on safe-blasting when out of pocket. There was nothing quite like the surge of adrenaline a man experienced upon opening a mangled safe door. It was like waiting to see whether a bet on Safe, Gold and Dynamite had won the trifecta. It was risky stuff, but on the right day it could yield a spectacular return. And, just as race horses were to be found at turf clubs, so dynamite and gold nestled in mining towns. Only days after his release from Mount Eden, on 8 December 1896, he entered Paeroa, at the foot of the Coromandel Peninsula, 70 miles south-east of Auckland. The village itself had almost nothing to offer a set of needy ex-convicts, but it was only a short walk from the near-exhausted Ohinemuri goldfields.

They travelled separately to Paeroa, having agreed to meet later that night at a paddock on the village outskirts, where they would doss down for the night. In mid-morning he slipped beneath a bridge on the edge of the settlement and hid a leather bag containing the most incriminating tools in thick bush. The bag was discovered there, weeks later, by a miner out on a riverside walk with his dog. McLoughlin ensured that, with the exception of some pieces of loose wire needed for lock-picking, his pockets were completely free of items of interest to nosey policemen.

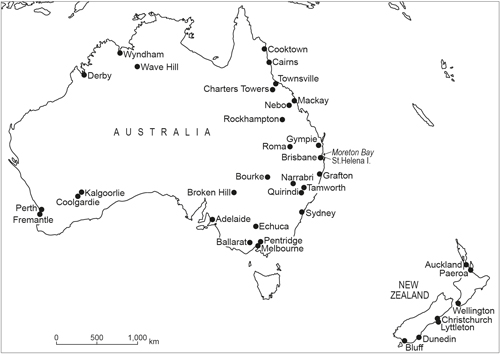

Australia and New Zealand

The condition of his artificial hand, however, was a cause for concern. It was five years old and irreplaceable; he felt incomplete without it and remained at pains to protect the retractable fingers with a glove. He had taken to removing the prosthesis whenever possible so as to minimise the possibility of further damage. Together with the wires, rolled into a blanket, it made the familiar ‘swag’ that so many antipodean labourers carried, tied across their shoulders, when tramping the countryside in search of casual labour or a place to sleep.

After lunch he wandered about for a while, but it was a Sunday and there was time to kill. By late afternoon he was reduced to ‘idling about the township, sitting on doorsteps’. The light was fading when the village’s night watchmen, Constables Beattie and Russell, came on duty. They did not recognise him, but he was a man without accommodation, a potential menace to the rural idyll of lower Coromandel. He gave them no cause for alarm and they merely watched him until close on midnight when he suddenly moved out of the village and up towards the paddock. If he slept there, and was a man of no fixed abode, he was a vagrant.

They gave him half an hour to settle in and then made their way to the paddock where they ‘found him, and another man lying down together with a blanket over them’. His companion may have been a younger man he was familiar with – something of a pattern in his life. The police either recognised, were not interested in, or were more sympathetically disposed to his partner. They rousted the pair, searched McLoughlin but, finding nothing incriminating, asked where his ‘swag’ was stashed. He told them that he had none, but they soon uncovered the ‘dummy hand’ and the wires which, he told them, were needed to repair his failing prosthesis. Not persuaded, they arrested him for ‘vagrancy’.2

Given his immediate past, he told them he was ‘John Dell’ but, when pressed, confessed to being ‘Thomas Kenny’. The Police Gazette revealed a criminal record, a recent release from prison, and his status as ‘a dangerous criminal’. The wires suddenly assumed greater importance than any possible charge of vagrancy. Within days he appeared in the Police Court, where he was again charged with being in possession of ‘house-breaking implements’ and committed for trial.

On the way back to Auckland, where he was due to appear once again before the formidable Justice ET Conolly and a jury, ‘Kenny’ was escorted by officer Tole. Chatting to Tole, he arrived at the mistaken conclusion that the policeman was sufficiently amiable and pliable for him to be able to ask for assistance. It may have been a mistake predicated on the lenient treatment that his paddock partner had received at the hands of the police. He confided in Tole and told him that the evidence against him did not lie in the wires found on him at the time of his arrest, but in a leather bag hidden below the bridge back in Paeroa. He asked Tole to recover and destroy the bag and its contents. Perhaps predictably – but it is hard to know because it was a question of judgement – Tole proved unwilling to help. In any case the question soon became irrelevant when Garner, the miner from Waitekauri, went out on a stroll and stumbled upon the bag. Within days of his release ‘Thomas Kenny’ found himself back in prison, at the misleadingly named Mount Eden, awaiting trial.3

Given the delays attendant upon the discovery of the bag and yet more police work, it was 9 March 1896 before the case was heard. ‘Kenny’ chose not to give evidence in his defence but did address the jury directly to tell them that he had used the wires discovered in his swag to repair his artificial hand. The jury retired for 15 minutes and presented Judge Conolly with a ‘guilty’ verdict. The convict, preparing himself inwardly for the sentencing to come, had reason to believe that he would receive a sentence of around 18 months

During his previous spell in prison, as ‘Kenny’ alias ‘Dell’ – the only identities by which he was officially acknowledged in the country – he had earned a remission of sentence for good behaviour. As ‘Kenny’ he had never been convicted of burglary or safe-blowing in New Zealand; indeed, he had never been found guilty of stealing so much as a cycle lamp, let alone the contents of a house or a safe. He had, it was true, been found with tools that might be used for committing a felony, but the police had been unable to link him to either a target or a victim. Nor had ‘Kenny’ or ‘Dell’ ever resisted arrest, or attempted to escape from police custody, or from prison. McLoughlin had found himself in a similar position once before, on the frontiers of Africa but, even there, in wild Johannesburg, such sentences were usually within reasonable limits.

As he already knew, but might not have factored into his calculations, since his last appearance in the Supreme Court the Imperial Eye had focused on the North Island, linking his past life – as ‘Jack McLoughlin’ – to his present one as ‘Kenny alias Dell’. Officials in Wellington now bore information about his past but were unable to officially confirm or deny it. Nor were they at liberty to use it for their own ends in open court, or to disclose it to the press. It was true that as ‘Kenny’ he had once been found to be in possession of explosives, but that in itself was not an offence and there was nothing known about ‘Kenny’ that warranted his classification as a ‘dangerous criminal’. Any information to that effect could only have been transmitted by the Imperial Eye. The question then became, who was in the dock – McLoughlin or ‘Kenny alias Dell’?

On the modestly populated North Island, an Eton-educated Judge of the Supreme Court would have been at home in the company of the Governor of New Zealand who had solicited expert opinion as to whether or not McLoughlin might be extradited legally. It was unlikely that talk about a man wanted for murder in Johannesburg did not circulate in the formal or informal legal circles that Conolly, who had been a barrister in England for 13 years, moved in.4 And, even if Conolly had not heard about it, the Police Gazette – easily accessible to any Public Prosecutor – would have recorded clearly that ‘Kenny’ had suddenly, rather inexplicably, mutated into ‘a dangerous criminal’.

Conolly may not have been formally informed that ‘Kenny alias Dell’ was, in fact, Jack McLoughlin. He may also have remained sufficiently focused and professional not to allow unsolicited incidental information to affect his sentencing. Indeed, the sentence he eventually handed down to ‘Kenny’ was in line with that handed down by him and other judges in equivalent cases.5 Nevertheless Conolly too, seemed suddenly to be impressed by the potential menace that ‘Kenny’ posed to society. How could he possibly have reached that conclusion if he did not have access to the latest information about the Red Lion shootings?

His Honour [Conolly] in passing sentence said he believed the prisoner was one of the very worst characters he had ever dealt with – a most dangerous character. He was convicted before him a year-and-a-half ago for the very same offence, viz, of having house-breaking implements in his possession, and he was then sentenced to twelve months imprisonment so that he was out of prison but a very short time when he started carrying on the same old game, going to a place where he apparently had nothing to do, and being found with house-breaking implements in his possession. As to the leather bag, he was sure that the jury believed that it was the prisoner’s also. He [His Honour] would pass the heaviest sentence upon him that the law would allow, namely three years in prison with hard labour.6

It was a harsh sentence for a one-armed repeat offender whose ‘dangerous character’ appears not to have been demonstrated in the matter at hand. The convicted man obviously felt that he had been done a gross injustice and that the sentence was unreasonably arduous.

The prisoner made an effort to speak, but was removed from the dock by the warders. Before descending the stairs, however, he yelled out: ‘I’ll do it standing on the top of my … head, you ….’ For some minutes after the prisoner went below, a noise as of somebody banging against a door and being very violent was distinctly audible in the Court.7

It may have seemed like the ranting of just another oft-convicted man; an audacious and unforgiving criminal who had been willing to take the life of a former friend, someone with an unquenchable thirst for gold and a lust for life, a person who refused to underwrite his needs by doing manual labour in a world dominated by machines and worked for profit by men with capital in a system that many people found difficult to reconcile with notions of social justice. But, if one listened carefully, it was also the anguished plea of an Irish emigrant dispossessed by empire and famine, of a child labourer in the cotton mills of Manchester, of a boy from a broken home, of an adolescent ‘scuttler’ hurling abuse at a Magistrate, of a man who had the codes of masculinity imprinted indelibly on his mind, and of a lover betrayed.

With the notable exception of the attempted escape at Potchefstroom, he became less inclined to challenge prison discipline as he grew older. Indeed, there are indications that by the time he entered his late thirties, he had grown accustomed to prison regulations in the all-male environment of a ‘total institution’ – he could, as he said, serve out a sentence, even a lengthy one, standing on his head. He was not in the army or the navy, but prison was not without its stolen comforts and it offered its own securities; he was away from some other temptations, including alcohol.

Captain Dangerous, ‘one of the very worst’ men Conolly had ever encountered outside Eton, gave the authorities no cause for concern. He was the subject of minor official interest on two occasions in the year that he was taken back in at Mount Eden, 1897, and then once again, in 1898, when a letter confirming his presence in Auckland was sent to the Cape Colony. Other than that, nothing. Indeed, as he worked his way through the days, weeks and months of hard labour in the year of his release, the prison authorities were again sufficiently impressed by his behaviour to grant him a two-month remission of sentence. New Zealand cells had by then claimed four years or 10 per cent of his life up to that point, for merely manifesting the intent to commit a felony.8

* * *

The new century was beckoning when, at the age of 40, ‘Kenny aka Dell’ was released from Mount Eden for a second time, on 2 September 1899.9 The newspapers contained cheering news – the Imperial Eye was going to be averted from New Zealand for some time to come. Flushed with imperial loyalty and patriotic fervour, two weeks before a shot was exchanged, the Prime Minister of New Zealand, ‘King’ Richard Seddon, had offered to send two contingents of men to join British forces in the coming war in southern Africa.

When war was declared, on 11 October 1899, it proved to be immensely popular in the antipodean ‘Better Britain’, prompting the nation’s first contribution of troops to a campaign abroad. Over 6 000 volunteers flocked to the standard and the inhabitants of the North and South Island found that they disliked Afrikaners almost as much as they loved the British. For McLoughlin, once a military adviser to Makhado’s regiments, a man with his own reasons for loathing the Boers, it was all ideological manna from heaven. He would have known, better than most, what a war in southern Africa would entail. Dealt with in broad brush strokes so as to avoid unnecessary detail, the topic of the South African War may even have eased ‘John Dell’s’ travels as he made his way around the countryside in search of beer, a chat and a place to spend the night.10

But on his release, and determined not to be caught with the tools of his trade for a third time, he had other, personal, things to contemplate. Socially dead since he had fled the Witwatersrand, he felt an increasing need to get to Australia and seek out Tommy. Talking to his brother would help remind him who he was and where they came from – it might even help create a future of sorts. But how was he to avoid spending more time between four walls and behind bars in a country where vagrancy nets had been cast across every city and the countryside? How did one move through social terrain that was so very ‘English’ without falling prey to laws that might have been designed to snare an impecunious fellow? How was a man to get himself to a port where an old Jack Tar might get a berth aboard a vessel bound for Melbourne?

The response was ingenious. Part of the answer lay in his shifting shape. He needed an identity that English-New Zealanders would not be alarmed by; one that while being ‘other’, and that of an itinerant, was obviously not that of a ‘vagrant’ or ‘out of place’.11 Lancashire was full of such men – he had seen them himself, camped in fields, moving up hill and down dale and in the lanes of town and countryside alike.12 Why had he not thought of it before? True, like their brothers, the gypsies, they were objects of suspicion, but they were not arrested on sight unless something was badly amiss. It would require little effort – indeed he was three-quarters of the way there already. When pressed by the police he had insisted that he was ‘a native of Ireland’. Moreover, his interest in gold amalgamation, safe-blowing and plate-laying on the railways of Mozambique all combined to provide him with a working knowledge of metal-working. It was all so obvious! He was a tin-smith – an Irish tinker, no less, working his way across farms in the back-country and, like all the seasonally migrant sheep-shearers, making his way to the port closest to Melbourne, Bluff, at the southern tip of South Island.13

The first weeks out of prison, as he battled to get Auckland behind him, were demanding. Without start-up cash, food or clothing it was impossible to avoid the haunts of vagrants and, for a while, he must have relied on the support of a few recently discharged fellow inmates to penetrate much deeper into the countryside. The rural economy was improving slowly after a decade-long recession and casual employment was easier to come by in summer when light and warmth encouraged seasonal, outdoor labour.14 His needs were modest and he remained sufficiently disciplined to resist the temptation of trying to raise money by engaging in any risky project. It took a month or two, but he assembled most of the tools used by a tin-smith and extended his culinary skills. Cooking was a necessary part of survival for a ‘Puck of the Droms’, a ‘Trickster of the Roads’, as the tinkers had it. But it was also a skill that could be marketed on farms where teams of migrant male labourers gathered to do clearing, fencing, harvesting, logging or sheep-shearing. The observation that ‘God made the tucker, but the devil made the cooks’ was part of folk-wisdom in nineteenth-century New Zealand.15

All that summer, from October 1899 through to March 1900, was spent zig-zagging across from Hawke’s Bay to Taranaki and working his way down towards Wellington, at the foot of the North Island. Like most of those in his newly chosen profession, he manufactured or repaired the ‘buckets, scoops, mugs, milk cans or basins’ used in small country stores, on farms or in houses.16 But, when money was tight, tinkers were famous for being able to live off the countryside by hunting small game or dynamiting rivers for fish – things that ‘Dell’ knew a fair deal about.17

There was a significant overlap between the sub-culture of the many itinerant manual labourers lugging their swag about and that of the handful of tinkers moving steadily along country roads. An Irish tinker would have had little difficulty in segueing into a swagger should circumstances demand it.18 Both were said to have ‘a propensity to play tricks and general deviousness’, to be economical with the truth, share a belief in luck, love gambling, horse-racing and, of course, alcohol.19

The anti-clericalism of tinkers and a reputation for exploiting priests and nuns, too, would also have sat easily with the newest Puck of the Droms. Known to be unforgiving of his enemies, ‘Kenny aka Dell’ may also have taken on another element of the wandering tin-smith’s culture – the ‘withering curse’, the infamous ‘tinker’s cuss’.20 Bad luck had long dogged his footsteps, affecting not only him, but those friends and associates around him. It had cost the Hadji his life. The tinker’s curse, however, was consciously directed outwards, towards those intent on thwarting him. For the superstitious, it may be worth noting how, for those who crossed Jack McLoughlin’s path in the closing years of his extraordinary career, the tinker’s curse posed a real threat.

Remarkably, ‘John Dell’, as he now preferred to present himself, managed to avoid a criminal charge throughout that summer. It bore testimony to the fact that there was more money than usual circulating in rural areas. But in late autumn his fortunes took a downward turn. With work falling away faster than the leaves off the trees, it became difficult to meet the everyday need for food, heating and shelter, let alone save for a passage to Australia. Even in the relatively milder climate of the North Island, winter quickly drove the hungry and homeless towards urban areas where the chances of survival were always better than in the countryside. But cities, and especially ports, came with all the familiar sirens. Bars and hotels provided sailors not only with companionship and warmth, but opportunities for drinking, gambling and casual sex. By mid-July he was without funds and firmly stranded in Wellington. For all the difference it made, the short 12-hour journey down the Cook Strait, out of Wellington and then south to Lyttelton, on the Canterbury shore of the South Island, might as well have been as far away, and taken as long, as a journey to Cape Town via Cape Horn.

He may have been acting on his own when he stowed away aboard the SS Rotomahana, but what is more likely is that he got some help from a crew member encountered in a bar. The steamer, it was rumoured, had originally been built for a wealthy prince, back in 1879, but the Union Steamship Company had had it refitted so that it could carry 300 passengers and a limited amount of cargo. Its regular run was between Sydney and eastern ports of the North Island but, that July, the company diverted it from the usual trans-Tasman route. It was bound for Lyttelton where, like the Mount Sirion before it, it may have been collecting horses – this time not for India, but for the war in southern Africa, which, by the time it was done two years later, had drawn in more than 8 000 horses from far-off New Zealand.

The Cook Strait posed a serious challenge to navigators at the best of times, let alone in midwinter. But, while the ship’s passage was without incident something went sadly wrong for the stowaway. Before he could smuggle himself ashore at Lyttelton, let alone reach nearby Christchurch from where he hoped to work his way to south to Bluff, he was found out. He was unable to pay the third-class fare; a constable was summoned and he was arrested. Back in Calcutta the police had provided a fugitive from justice with a new suit and made sure he left India. In Lyttelton they were waiting to ensure that he did not enter Canterbury a free man.

Lyttelton was in celebratory mood. The first British settlers destined for Canterbury had set foot there exactly 50 years earlier. Their descendants and new arrivals alike deferred to none when it came to Christianity, the bifurcated and racist patriotism of ‘country and empire’ or hatred for the empire’s enemies – the Afrikaner republicans of South Africa.21 Here then, isolated by Lyttelton’s steep cliffs, was Little Britain, the longed-for Better Britain, undiluted by other cultures, ethnic groupings or races; the way God and Queen intended an outpost of empire to be. As they made their way up the hill towards the police station, in a square off Sumner Road, the constable and his prisoner passed the ‘British’, ‘Canterbury’ and ‘Empire’ Hotels. Later that year, as part of the Lyttelton Jubilee celebrations, ‘Much amusement was created by a nigger on horseback holding an effigy of that slippery Boer General de Wet, who was being ill-treated in a manner that met with general approval.’ And north of Christchurch, in Amuri County, some of the landlords were still referred to as ‘Kaffirs’ because, a decade earlier, they had threatened to import semi-skilled blacks from the Cape Colony to break a strike by shearers.22

‘Dell’ got the point. Empire transmitted class and colour prejudice almost as readily as it built trans-oceanic notions of ethnic solidarity and political loyalty forged from shared language and skin colour – indeed, it was two sides of the same coin. In the relatively cosmopolitan and more open environment of the North Island, almost one in five inhabitants was of Irish descent, with significantly more Catholics than Protestants.23 But on South Island things were rather different. So, whereas he had told the Auckland police that he was ‘a native of Ireland’, born in 1858, in Lyttelton, he informed them he was ‘a native of England’ and, for good measure, lopped four years off his age, claiming to have been born in 1862. It mattered little, the missing arm spoke a truth all of its own. It never lied and it was all recorded in the Police Gazette.24

The Justice of the Peace who presided over the Police Court, Captain Marciel, had seen it all before. Deserters, runaway sailors and stowaways were no novelty in Lyttelton. There were only two cases before him that Tuesday morning, 24 July 1900 – a drunk and a stowaway. Remorseful drunks were as common as seagulls’ cries, so he convicted the first offender and discharged him with the customary caution. The man had done no harm or damage to property. The stowaway, other than having only one arm, also presented nothing remarkable. If it were up to him, he would send him packing as well. He was reluctant to send a man who was so obviously down on his luck to prison. But Lyttelton lived off the sea and the shipping companies were not to be trifled with, so he sentenced him to a fine of £1, or 14 days, hoping that the poor fellow would somehow come up with 20 shillings. He could not, so he was taken off to jail, two blocks up from the wharf, into Canterbury Street, where, today, two portals are all that remain of a building that once held the Terror of all Johannesburg.25

A fortnight’s accommodation and food in winter were not the worst thing that could befall a penniless man in a vagrant-obsessed society. He seemed fated to be discharged from prison when spring was in the offing, but the on-going chill made him reluctant to set off for one of the southernmost settlements in the world. Invercargill and Bluff lay some way below 45 degrees south and he felt unable to risk going there. Not only would casual jobs be few and far between, but the cold forced one to seek refuge in places that were likely to be well policed. So, when he was released, on 7 August 1900, he managed to raise the money for the short train ride to Christchurch without raising the ire of the authorities. It is not clear how long he spent in the city, but when it eventually warmed up some weeks later, he gathered up his blanket, tin-smith’s tools and a billycan and set off to explore the side roads of Canterbury against the backdrop of some of the most beautiful snow-clad mountains in the world. He did not emerge for nearly three months.

He got to do a good deal of catering for itinerant hired help on out-of-the-way stations where a cook of any sorts often earned about two-thirds of the wages paid to a skilled worker. It brought in a reasonable income and provided steady work in between the irregular flow of cash that came from the piecework that marked out tin-smithying. Cooks were notorious for ‘going on the booze’ but most remote rural areas had their own externally induced discipline: with fewer bars to pull him towards the beer, he managed to stay out of trouble.26 There was also a great deal of camaraderie and companionship among the swaggers which made the experience tolerable – at times, positively pleasant.

As September came he noted that many of the more adventurous, trans-Tasman sheep-shearers were, like migratory birds preparing for the change of season, becoming restless.27 There was much talk about the imminent need to get south and board ships bound for New South Wales and Victoria. This was in order not only to profit from the Australian sheep-shearing season – which, depending on where the stations were, ran from August through to December – but also so as not to miss out on Marvellous Melbourne during the most exciting week of the year. The first Tuesday of November each year, without fail, brought the country to a standstill as the most famous two-mile horse race in the world, the Melbourne Cup, was run amidst a carnival-like atmosphere. Among shearers, ‘The one subject that overshadowed all others, was horse-racing. The Christian calendar was abandoned, the years were known by the name of the horse which had won the Melbourne Cup.’28

No stranger to Melbourne himself, McLoughlin could relate to this form of popular madness. But a winged bird that had lost its financial fat on a Wellington waterfront the previous year was in no position to undertake the season’s migration. He held out for as long as he could, but with the prospect of yet another winter in New Zealand unthinkable, the appeal of the Southland ships, with or without funds, became irresistible. He had long since abandoned the thought of getting to the Cup on time when he put the sheep runs behind him and re-entered Christchurch on 10 November 1900. It was not as though nobody cared. His absence had been noted by the usual police seine-netters, keen to haul in any and all ‘vagrants’ that might pollute the otherwise pristine environment.

But ‘Dell’ was sober, in control of himself and had enough cash to cover the cost of a ticket south – perhaps only as far as Dunedin, maybe farther – where he would soon become somebody else’s responsibility. The police gazetteers, however, could not resist hauling him in and shaking him down to see what additional information they might tumble out of a ‘dangerous criminal’. They got nothing new, or of value, out of him. In the end they were left to note that he was on his way to Southland, where he would probably again be turning his hand to doing some cooking and tin-smithying on a few of the remoter sheep runs.29

And so, somewhere out there, in one of the coldest and least densely settled parts of the British Empire, between November 1900 and April 1901, the Imperial Eye, as yet without the benefit of passport control in port cities, again lost sight of its quarry. By the time that it next got around to scanning the horizon for him, in August 1901, there was no trace of ‘Tom Kenny’, ‘John Dell’ or ‘Jack McLoughlin’.30 The injured bird had somehow got itself to Bluff – and from there, it could have flown off in any direction.