CHAPTER SIX

Escape into Empire

THE VOYAGE OF THE ALBATROSS

— 1880–1881 —

Ship me somewhere east of Suez, where the best is like the worst,

Where there aren’t no Ten Commandments, and a man can raise a thirst.

The Europeans’ fifteenth- to seventeenth-century voyages of discovery not only conquered the southern Atlantic, beating a new pathway to India, but also helped western powers of the day chart the emerging outline of the globe. Britain’s interest in the ocean off its western shores, however, was not secured until Nelson defeated the French and Spanish navies off Trafalgar in 1805. That victory gave the fleet control of most of the world’s oceans, but it was the defeat of Napoleon on land, at Waterloo in 1815, that consolidated Britain’s claim to be the world’s pre-eminent nineteenth-century power. Backed by an industrial revolution gaining in momentum after 1830, the peoples of the island spread out into an expanding world at an increasing rate. By 1870, 200 000 British subjects a year emigrated into a formal empire of conquest and settlement, as well as to other territories where its influence held sway.1

Huge fortresses at Gibraltar and Malta safeguarded British trade around the Mediterranean littoral and helped check Russian ambitions in south-eastern Europe. Beyond the Horn of Africa, Britain used its foothold in India – then still approachable only via the Cape of Good Hope – to extend its reach into surrounding regions and the Far East. The end of the Opium Wars, marked by the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, opened China to foreign commercial interests; by the late 1860s, Hong Kong and the free port of Singapore in the Straits Settlement were firmly under British control. This eastward shift in the empire’s centre of economic gravity was further facilitated by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.2

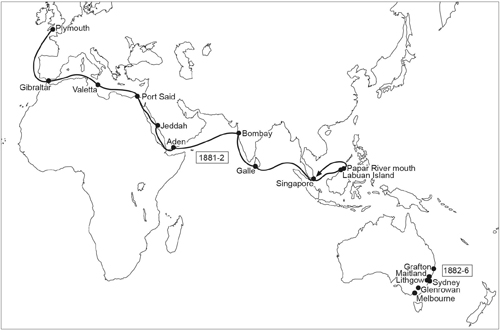

The Voyage of HMS Albatross, 1881–1882

The Mediterranean and seaborne approaches to India – which, after the Great Rebellion of 1857, housed most of Britain’s limited land forces – grew in importance. Not only did the Union Jack come to flutter over Egypt after 1882, but Aden and various ports down the East African coast assumed greater strategic significance. The British effectively controlled the Indian Ocean Basin, having earlier expelled most of its potential European rivals. Markets throughout the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans, first prised open through British insistence on ‘free trade’, were, after 1870, increasingly developed through the enforcement of policies that readily embraced tariffs and other forms of protectionism.3

Although in growing need of imported foodstuffs to feed its expanding urban population, Britain’s exports soared through most of the late nineteenth century as trade, backed by the gold standard, reinforced a rapidly integrating global economy. Awash with funds, British foreign investments grew dramatically after 1880, doubling by 1900, and then quadrupling by 1913.4 Even distant colonies, including Australia and New Zealand, benefited from robust economic health at the centre of the empire. Refrigeration and other scientific advances enabled them to expand agricultural production and add value to their exports by partially preparing meat and other edible products. The only notable faltering in the pace of economic growth came during the largely depressed 1890s.5

The economic consolidation of empire owed much to three further interconnected technological advances. Two of them traced their pedigree back to harnessing of steam-power during the earliest stage of the Industrial Revolution, while the third was electrically driven. The introduction of huge steel-hulled steamships in the 1880s reduced the tyranny of distance when it came to bulk transport and passenger travel.6 Voyages that had once taken weeks or months were dramatically reduced in cost and time. By 1885, poor emigrants travelling steerage on cutthroat Atlantic routes could purchase tickets between Hamburg and New York City for as little as seven American dollars. Passenger liners completed the journey from Liverpool to New York in just six days.

Port cities, in turn, were linked into gigantic trans-continental railway systems dating back to the 1870s. By the outbreak of World War I, the world’s most industrialised economies were served by tracks covering three-quarters of a million miles. Individually significant, the co-ordinated collective steamship and railway systems proved to be utterly transformative. Reductions in cost not only helped underwrite the export of raw materials and the bulk importation of manufactured goods, but facilitated the mass human migrations that characterised the age.7

On land the telegraph – supported by a network of undersea cables transmitting electrical impulses that by the late 1890s circled the globe – formed the economic nervous system of a globalising economy. It helped co-ordinate industrial muscle, enhancing productivity and lifting profit margins. About 8 000 miles of telegraph wires, in 1872, were extended to cover more than a quarter of a million miles by World War I, with 40 per cent of the lines owned by just one company, the London-based Eastern Telegraph Company. Government subsidies to selected shipping companies ensured the swift and reliable movement of commercial mail between continents. Domestically, huge quantities of handwritten and printed material were shunted to inland destinations by rail.8

There was an explosion in the volumes of economic intelligence and information available to, and needed by, a host of interested insiders. Agents, consuls, financial journalists and governments were in constant need of commercial data about the cost of raw materials, shipping rates, trading conditions, or the prices that processed commodities were likely to fetch in far-off markets. By the turn of the twentieth century London had an ‘imperial press system’ that was buying and selling news of all sorts in a way that was said by some to constitute a near ‘perfect feedback loop’.9

Of course, not all data was accessible through conventional channels, or freely available to anybody who might have an interest in it. As a global power Britain developed and maintained instruments of surveillance that linked London with its distant periphery in ways capable of guaranteeing the security of the empire. Westminster and Whitehall relied on an uninterrupted supply of confidential or top-secret military and naval intelligence. Law-enforcement agencies, too, used the telegraph and police gazettes to collate and distribute intelligence about criminals who were becoming more mobile.

Most official despatches, including those relating to law enforcement, only surfaced in the press in modified format and prosaic language – informing the public about the latest diplomatic, judicial or legal developments. While many of these flows of information were tailored to be audience-specific, moving along pathways linking imperial London to its outposts, they could, on occasion, go beyond their intended destinations. When forwarded directly between colonies, communiqués sometimes gave rise to unforeseen consequences. Newspaper reports of civil or criminal proceedings in Australasia might, for example, be forwarded to southern Africa and vice versa. This sometimes left businessmen or members of the public marginally better-informed about the inter-colonial movement of criminals and other shady characters in the commercial world than the local police.10 Informal cross-flows of information, together with routine official exchanges between the centre and periphery, meant that, by the late nineteenth century, inhabitants of the wider Anglophone world, law-abiding and law-evading alike, were being subjected to surveillance by what we might term an Imperial Eye.11

The Eye may have gathered and interpreted the data that prompted ground-based actions throughout the empire, but the ultimate enforcer in the ‘British World System’ during the Victorian era was the Royal Navy. Post-Napoleonic governments seeking to entrench British hegemony expanded the navy. But, by the mid-nineteenth century, as the switch from wooden to iron-clad ships gathered momentum, Conservative and Liberal administrations alike vied to limit naval expenditure.12 For most of the 1870s, naval estimates were restricted to around £11 million per annum and, at one point, construction was reduced to the production of just five armoured ships in five years. Notwithstanding, the navy remained formidable and in 1877, comprised over 550 vessels with a combined tonnage of over 675 000 manned by 25 000 officers and men, 6 000 marines and close on 3 000 boys. The navy policed imperial waters and divided the world’s oceans into just eight overseas stations.13

* * *

When McLoughlin boarded HMS Albatross in Plymouth, in November 1880, the navy’s overall brief remained broadly unchanged. It had to safeguard incoming food supplies and the physical integrity of the British Isles, protect the nation’s expanding trade by ‘flying the flag’ and assist in combating piracy. Yet, for all that, something was different. The most important drivers of foreign policy had recently changed quite dramatically.

In 1876 a section of British public opinion that extended beyond the true believers in the ruling Conservative Party had become perturbed about foreign policy. Disraeli’s principal ally against Russian expansionism in the Mediterranean – the Ottoman Turks – had been party to a series of atrocities in Bulgaria. Concerns about this were exacerbated by the manifest decline in Ottoman power and by the Turks’ inability to enforce their political will in a near-bankrupt Egypt that stood astride the decade-old Suez Canal and the shortened sea-route to India.14 Gladstone, in the first electoral campaign in the era of the extended franchise, made foreign policy the focus of his famous Midlothian campaign of 1880. The Liberal Party displaced Disraeli’s Conservatives at the polls and Gladstone became Prime Minister of Britain for a second time.

The trans-hemispheric voyage of the Albatross in 1880–81 began at a moment of heightened uncertainty in the Middle East. Deep-seated economic problems and growing political instability there not only threatened Britain’s trading interests in the Mediterranean but potentially barred easy access to the Suez Canal, the ‘Highway to India’ and all that lay east and south of it. The timing and trajectory of the patrol laid out for the vessel by the admiralty was routine insofar as it traced established pathways of importance to the empire, but also ‘special’ given that the warship was to linger in the Mediterranean.15 The Albatross and Jack McLoughlin were bound for Suez and beyond.

The ship was one of six cost-cutting sloops built by the navy over just 24 months in 1873–74. But, caught amidst the tempests of rapid technological change, the sloops were hard to maintain and obsolete almost from the moment they were completed. All six ships were sold before they had seen out two decades of service.16 Built around iron frames, the ‘composites’ were sheathed in copper and teak and driven by two-cylinder steam engines fed by three boilers fired from 100-tonne supplies of coal. Looking back on the golden age of sail as well as peering forward into a mechanised future, the sloops were equipped with three masts and rigged out in the manner of barques. Armed with two 7-inch and two 64-pounder guns mounted on pivots, the ship was manned with 13 officers, 19 petty officers, 62 seamen, 19 marines and 12 boys. Having undergone extensive shipyard repairs only the previous year, the ship was recorded as being in ‘good condition’ when McLoughlin joined it.17

Bound for Gibraltar, the Albatross left Plymouth in late November 1880 under the command of Commodore AJ Errington, an Irishman who had long since overcome a troubled past in the West Indies.18 The fortress at the Rock, befitting an outpost at the gateway to the Mediterranean, was a site of unceasing military and naval activity, provisioned by English merchant houses and Jewish traders, and supplied with fresh produce by several hundred Italians who hailed from Genoa. Focused and functional, the port was less exotic and socially turbulent than others in the inland sea, yet, perhaps significantly, had been the first such British outpost to establish an independent police force modelled along the lines of London’s Metropolitan Police. After a day or two the ship sailed for Malta, much closer to the heart of the new political storms.19

Malta, where the sloop was anchored for a week or more, was closer to the mariner’s dream of ‘Fiddlers Green’ – and McLoughlin’s taste – than was Gibraltar. First occupied by the British in 1800, the island had served as a secondary centre during the Crimean War. Since then it had been transformed by a never-ending flow of soldiers and sailors and tourists arriving by steamship. By 1880, Valetta boasted 20 hotels, scores of lodging houses and two theatres. A music hall was being built for artists seeking to avoid the English winter by offering programmes of classic Victorian entertainment. As in most places where they commanded a presence, the army and navy had done little to uphold the moral tone of a town that housed several churches and convents. The presence of unruly soldiers and sailors, it was said, had been complemented by the arrival of many Italian and Spanish artisans and a few Sicilian women of doubtful virtue. By the time the Albatross called, the town was experiencing significant problems with drunkenness, gambling and prostitution. Modern methods of detection and policing were being introduced, extending the vision of the Eye.20

With the Grand Harbour behind her the Albatross steamed east from Valetta, bound for Egypt, where, only a decade earlier, De Lesseps’s globe-shrinking construction, authorised by the Khedive Ismail Pasha, had been seen as the guarantor of Egypt’s economic progress. In the 1860s, the American Civil War and Cotton Famine had prompted a significant increase in the price of Egyptian cotton. Flush with funds and pleased with the French, ‘Ismail the Magnificent’ had commissioned a gigantic ‘statue of progress’, in keeping with the majesty of ancient Egyptian art, to stand at Port Said, at the western entrance of the canal. The work, by a Frenchman, Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, was inspired by the Roman ideal of liberty and built on a scale that would allow all to see the light that Egypt was destined to cast over Asia. But by the time the Albatross made port, Ismail Pasha was no longer in control, the country was bankrupt and so politically unstable that just months later, in 1882, it was ‘temporarily’ occupied by British forces. The Statue of Liberty was by then destined for the harbour at New York City and the ‘temporary’ British presence in Egypt set to last for another 66 years, until 1954.21

Mirroring the growth in world trade, the number of ships passing through the canal annually had increased from about 500 in 1870, to more than 2 000 by 1880. But with fewer than 10 ships a day capable of making the passage in each direction, the Albatross, along with dozens of other vessels reliant on sail, was forced to lie at anchor in Port Said for several days waiting for its turn. The small desert town, already acquiring a reputation for fraud, immorality and sleaze that was to grow exponentially during the twentieth century, had little to recommend it. The sloop passed through the canal on 15 December 1880 and, upon entering the Red Sea, hugged the northern shore and made Jeddah three days later.22

For devout Muslims, Jeddah was but one of many ancient portals on the road to Mecca, which lay panting in the desert sun 40 miles inland. For the faithful, the Hajj was the principal marker in a rounded religious life, but the journey was eclipsed by the experience of entering the Masjid al Harma mosque. A sense of spiritual renewal came with the ritual circling of the Kaaba on the site where Abraham had been called upon to make his sacrifice. The practice of the Hajj extended back for many hundreds of years; indeed, for businessmen and the inhabitants of Jeddah one year was much like another. But 1880 was different. When the Albatross docked, harbour-side labourers and outraged traders in the market were still poring over the details of one of the greatest maritime scandals of the age. For the faithful, it proved again that one’s ‘fate’, or what some called ‘destiny’, lay only in the hands of an all-merciful Allah.

In mid-July, the SS Jeddah, Union Jack aloft, had left Singapore and called in at Penang, up the Malay peninsula. By the time the ship set course for Jeddah, it was carrying over 1 000 men, women and children from the Malay states. But after experiencing heavy weather in the Arabian Sea, the Jeddah took in water and started listing badly. The captain, his wife, first mate and others, fearing the worst, lowered a boat and abandoned ship, leaving the faithful to an uncertain fate. The captain and his party were picked up by a passing vessel and ferried to Aden. There they told a tale about storms, a foundering ship, and frightened passengers – some of whom, they said, had become violent.

But the Jeddah had not sunk. Days after being abandoned, the drifting hulk and its helpless passengers were taken in tow by a French vessel. When the pilgrims disembarked at Aden, their story gave rise to a storm of harbour-side accusations and questions about integrity, morality and professionalism. For McLoughlin, raised on stories about the choices men made between courage and cowardice, the plight of the Jeddah would have offered another salutary tale. In naval circles reports about the shortcomings of the captain and his crew had an enduring relevance and refused to die. In 1883, a young Polish seaman passing through Singapore picked up on it and later, as Joseph Conrad, turned it into Lord Jim, one of the greatest seafaring novels in the English language.23

The crew of the Albatross, like sailors everywhere, were for the most part more interested in their shore leave than the religious significance of the port they happened to find themselves in. Christmas was celebrated in Jeddah in the way that came naturally to Jack Tars. There was more drunken carousing on New Year’s Day 1881, after the sloop had slipped down through the Straits of Bab al Mandab and berthed in Aden.

The 10-day stay there testified to the importance of a port that had first attracted imperial interest half a century earlier, in the late 1830s. The British had occupied the town when they became exasperated by pirates menacing ships of the East India Company plying the Arabian Sea. Thereafter, the coastal stronghold was administered from Bombay. Bombay was the financial and commercial hub of a region that included not only the Middle East, but also much of the African coastline stretching down to Zanzibar and, albeit more tentatively, as far south as Lourenço Marques.24 Those economic strands were strengthened when the submarine cable linking Bombay to London, via Aden, Suez and the Mediterranean, was completed in 1870. Aden served as a major coaling station, supplier of boiler water, and communication hub for the region.

From Aden they set out across the Arabian Sea, and in mid-January arrived in Bombay, where they spent close on two weeks. Benefiting from the favourable trade winds throughout mid-century, Bombay was in full flight economically. Construction of a local railway line, in 1853, had been followed by a huge spurt in the development of a trans-national system in the 1860s which, in turn, served regular steamship connections up and down the west coast, leading to the establishment of a Port Trust in 1870. By 1860, Bombay, already the largest cotton market in India, boasted hundreds of mills. As in Egypt, disruptions occasioned by the American Civil War and the Cotton Famine spurred growth. The opening of Suez helped; by 1881, Bombay had three-quarters of a million people.25

Like many larger English cities, Bombay was undergoing something of a municipal revolution. Like Birmingham and Manchester, the city was benefiting from a new drainage system and piped water. There was also talk of experimenting with electric lighting in the Crawford Market. New public buildings, including a museum, post office, railway station and university, testified to growing civic pride. Numerous trading houses and a thriving stock exchange underscored the city’s economic vibrancy. In the Falklands Road, low-life haunts functioned reasonably openly despite a recent clampdown by the Commissioner of Police. But more importantly, Jack’s ears would have pricked up at rumours about the possibility of acquiring wealth in ways that lay beyond the law. Bombay offered a convenient entry point into the Indian interior and the Kolar goldfields, 500 miles south, in Mysore.

Until it reached India, the Albatross had had little to do other than fly the flag and help keep clear one of the most sensitive economic and strategic arteries in the imperial system. But the admiralty needed the warship for more important assignments and pressed the captain to proceed to the South China Sea. Errington, however, had reservations about the ship’s condition. The sloop was proving difficult and expensive to maintain because of the composite materials used in its construction. A compromise was reached and the Albatross instead set course for Galle in Ceylon for the necessary maintenance work.26

They left Bombay on 25 January 1881, headed south, rounded Cape Comorin and then, ignoring Colombo, pushed on to the fine natural harbour at the south-western tip of Ceylon. Galle, best seen as the southernmost point of central Asia, commanded a magnificent aspect. Its strategic position allowed one to scan the surrounding ocean through 300 degrees, taking in most of the southern world and good deal of the near northern. It had been a predictable port of call for the earliest navigators, including the Chinese admiral, Zheng He, who had visited it twice in the early fifteenth century – long before Atlantic explorers had found their way round the Cape to India. Once the Europeans found it, the island was occupied first by the Portuguese, then the Dutch and then, in the early nineteenth century, by the British. Galle was an obvious port of call and point of transshipment for modern mail ships, but less suited to inland commerce, which was increasingly focused on Colombo.

A turnstile to the hemispheres – east and west, north and south – Galle was as good a point as any in the world to jump ship and it must have tempted McLoughlin to think through his future anew. Like most warships, the Albatross was constantly bleeding disillusioned or unhappy sailors and taking in new recruits. It had already drawn in several men of different nationalities in Gibraltar and Malta. The fact that he chose not to desert in Ceylon may have been a sign that he already had another, more promising, destination in mind. He was aboard when, a week later, the sloop set course for Phuket on the Malay peninsula but then swung round, south-east, pushing through the narrow Straits of Malacca, and on towards that most strategically situated city, Singapore.

Little wonder that the navy fell out of love with sloops almost as soon as they were launched. It took more than two months to get the Albatross ship-shape. The vessel was in the harbour between 22 February and 27 April and, during that time, was cleaned, re-painted and re-provisioned for cruising in the unsettled South China Sea. The Imperial Eye duly noted McLoughlin’s presence when the census was taken on 3 April 1881.27 Eight weeks in Singapore left him with more than enough time to familiarise himself with those aspects of urban south-east Asian society that appealed to sailors. But it also gave him the opportunity to find out more about the frontiers and gold mines that had sprung up in many of the older British colonies spread across the southern Pacific.28

The Malay Peninsula, which enjoyed a reputation of its own for gold deposits, had for aeons attracted enterprising Chinese immigrants. Later, it became the focus of intense competition by rival European powers for trading rights. The English, Dutch, Portuguese and Spanish had all staked out interests in the region, but after the Napoleonic Wars it was the British East India Company, already based at Penang, that had started taking a more active interest in the southern tip of a peninsula that was rightly said to hold the ‘Key to the East’. In 1819, the legendary Stamford Raffles, amidst protests from the Dutch that lasted until the matter was formally settled five years later, picked out Singapore as the site for a ‘free trade’ port that would soon come to dominate the region.

Seven years later, in 1826, Singapore, Malacca and Penang were drawn into a single administrative entity – the Straits Settlement. That arrangement lasted until the Company was effectively nationalised by the British government after the ‘Indian Mutiny’ of 1857. But, because coastal trading remained predominant, relatively little was known about the interior, and even after 15 years there were still no reliable handbooks or maps of the peninsula – let alone the myriad islands that dotted the South China, Celebes and Sulu Seas, in which pirates had reigned supreme for decades. This situation was only corrected when it became better known that, in addition to gold mines at Raub, there were enormous deposits of tin that had long been mined by the Chinese, with the help of 40 000 labourers. Once the Cornish tin mines started petering out, in the 1870s, the British moved in to control the supply of a metal that was light, durable, well-suited to food packaging and easily transportable.29

The prosperous peninsular economy was served by a complex multi-racial population that remained notoriously segregated. Numerically preponderant native Malays were favoured by the British for posts in the lower reaches of government and the police, but the natives were out-muscled in the wider economy by Indian merchants who, in turn, bent the knee before Chinese interests in the growing palm-oil trade. The Chinese, besides dominating many sectors of the formal economy, were sometimes also involved in illegal operations controlled by gangsters belonging to secret societies whose origins lay back in southern China.30

In a way, Singapore provided 22-year-old Jack McLoughlin with his first exposure to a pioneering settlement, one replete with an ethnically diverse underworld with distinctive interests in gambling and prostitution. There was something about the economic pulse of the place and the opportunities it presented that excited him, even if he knew that as a European outsider he could never penetrate it successfully. It was the frontier situation that appealed to him – and it only whetted his appetite to find one where he was more at home in terms of language and culture.

These impressions were still settling in his mind when the Albatross weighed anchor on 27 April and put Singapore behind her. The sloop slipped into the forbidding South China Sea, and then set a north-east course. For the next five weeks they were well beyond urban frontiers, out on patrol in one of the most unhealthy extremities of empire. The small island of Labuan, off the north-western coast of Borneo, was an outpost used to confront pirates and protect the Hong Kong trade. It had been ceded to Britain by the Sultan of Brunei in 1846 and become a Crown Colony. A fluttering sense of optimism seemed vindicated when, not long thereafter, an abundant supply of coal was discovered. The famous ‘White Rajah’, James Brooke, Governor of Sarawak, under whom the tiny colony fell, then sought to encourage itinerant Chinese traders to settle on what previously was an uninhabited island.

A promising start faltered and, by the 1870s, the British were looking to divest themselves of the tiny, malaria-infested colony. But they suddenly had second thoughts when it appeared that some of their regional rivals were set to exploit timber resources and trading opportunities in the neighbouring territory of what today is Sabah. An increasingly unsettled political environment prompted Westminster to rethink its strategy and, in 1881, the government granted a Royal Charter to the British North Borneo Company. Diplomatic niceties, the lingering presence of pirates and economic uncertainty all demanded the presence of the Albatross.

After exciting stays in Bombay, Malta and Singapore, a month-long patrol of remote outposts plagued by malaria and other tropical diseases proved singularly unpleasant. The sloop sailed north from Labuan to the Papar River mouth and then on to Abai Bay before returning to its island base. The precise circuit they followed – from Labuan out to the Saracen Bank poised at the edge of deep waters – seemed pointless since there were no encounters with pirates worth reporting. They merely rounded the reefs and then, turning south-west, retraced their course down the Sarawak coast before re-entering Singapore in the first week of June.31

The crew was pleased to be back in port but, within hours of their return, there was disturbing talk among the officers about the ship having to return to Sarawak to take up a new assignment. The navy was assembling a squadron that would undertake several additional patrols in the South China Sea before heading for Hong Kong, where it would be based for several weeks. Like many an Irish emigrant before him, McLoughlin, bent on going south and east, found the prospect of more-of-the-same singularly unappealing. When HMS Albatross set sail from Singapore, on 8 June 1881, he was no longer part of the ship’s company.

It was a criminal offence to break contract with the armed services. Most deserters, many of whom continued to move about the oceanic world as seamen in the Merchant Navy after they had abandoned their ships, adopted aliases when they found themselves in ports where the British authorities had an official presence. McLoughlin, feeling his way around the fringes of the empire for the first time, almost certainly did so. Always laconic and loath to divulge unnecessary information, he remained understandably reluctant to talk about his desertion from first, the navy and then, later in life, the army. But, even allowing for that, there may have been other reasons for his profound silence about the six months spent in the navy and the voyage of the Albatross. It was, after all, at a time in his life when he was probably both more anonymous and more sexually active than any other. He may have left the navy, but the navy had not left him, in any event. For close observers, he manifested several enduring tell-tale signs of time spent at sea.

After Singapore, he walked with a distinctive gait that the navy and later the army contributed to.32 The senior service left him with a lasting appreciation of naval office and rank in matters of discipline.33 In the 1890s, while on the run from the police and already a man of significant stature in his own right, he served as a mercenary, reporting to another deserter from the navy known only as ‘the Admiral’. Two decades after that, when he became violent on an ocean liner, the intervention of the ship’s captain was sufficient to haul him back into line.34 The armed forces may also have imbued him with an enhanced sense of racial superiority. The authority exercised over Arabs, Chinese and Indians and routine arrogance displayed towards them in countless day-to-day situations had deep cultural roots in western societies. But, for ordinary soldiers and sailors, that power was often reinforced through the exercise of brutal, direct physical force in social encounters that were far from the field of battle.

For the Manchester-born son of Irish immigrants imperial arrogance could be problematic. One of the tattoos McLoughlin left the navy with bore the coat of arms of the land of his birth, England. It was a prudent display of patriotism for an English sailor on a British warship. But, he also sported the coat of arms of the United States of America – an erstwhile British colony that had gained its independence through force of arms. America was also famous for the generous reception that it had accorded Irish refugees and for political sympathies that were pro-Irish.

But there were other puzzling ambiguities to McLoughlin’s bodily displays. In keeping with the image favoured by sailors, his upper arms were festooned with tattoos of a ‘ballet girl’. It would certainly be surprising if he and other sailors on the Albatross had not visited the usual harbour-side dives pushing alcohol, encouraging gambling or selling sex during their voyage across half the world. Yet, if there was one thing that characterised almost his entire life, then it was a consistent lack of interest in women. His preference was always for male company – in army barracks, in bush camps, out drinking, on the roads, on board ship or in prison.35 The ‘ballet girls’ may have helped mask more complex attitudes, choices and behaviours.

Finally, if the navy did nothing else, it gave him an idea of the scale of empire and a slightly better understanding of the strengths and limitations of the Imperial Eye. The capacity and reach of law-enforcement agencies across the colonies varied greatly. A man on the run stood a better chance of avoiding the authorities in Bombay than he did in Singapore. And, during the four years that followed – from 1882 to 1885 – he learnt that Australia was perhaps the best country of all in which to hide. Almost nothing is known about him during that period. It was a good time in his life, but the Imperial Eye was becoming sharper with the passing of every year.