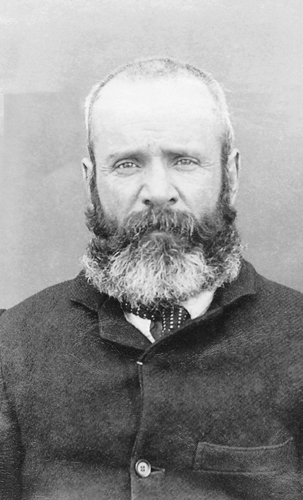

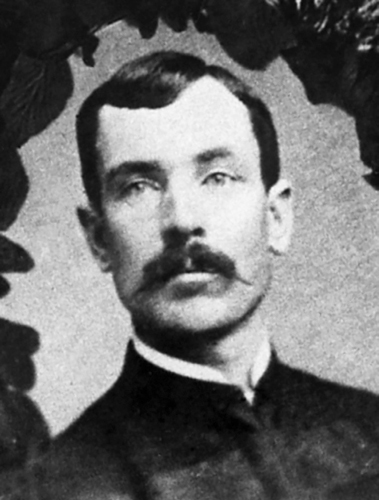

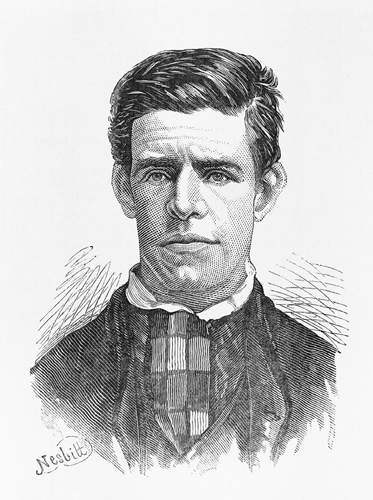

A spate of robberies at railway stations in rural New South Wales in 1902 culminated in gang leader ‘John Bourke’ being sentenced to a year’s hard labour in Tamworth Gaol. This mugshot is also the only surviving likeness of Jack McLoughlin, who shot George Stevenson, his underworld-intimate turned police informer, in 1895. NEW SOUTH WALES STATE RECORDS

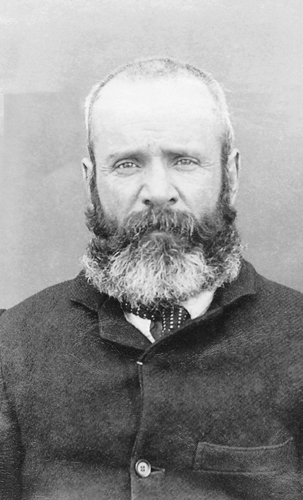

In 1859 the historian Hippolyte Taine, visiting Manchester, noted a factory, a ‘rectangle six storeys high’ in which thousands of workmen were ‘regimented, hands active, feet motionless, all day and every day, mechanically serving their machines’. It could, he wrote, have been a hard labour penal establishment. Above, Murray Mill on the corner of Bengal and Union streets, Ancoats. MANCHESTER LIBRARIES, INFORMATION AND ARCHIVES, MANCHESTER CITY COUNCIL

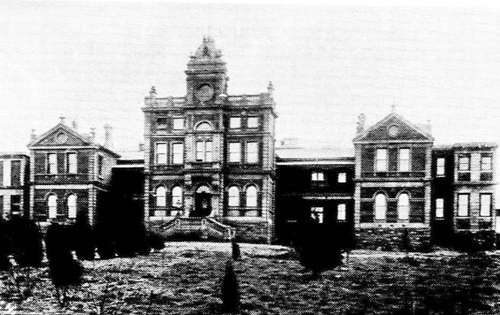

The west wing of Belle Vue Prison, a ‘factory’ for reforming character, saw McLoughlin do three months’ hard labour for the theft of a pair of boots in 1878. MANCHESTER LIBRARIES, INFORMATION AND ARCHIVES, MANCHESTER CITY COUNCIL

A roof-top view of Ancoats, ‘the world’s first industrial suburb’, the most densely populated Irish quarter in Manchester ‒ and birthplace of Jack McLoughlin in 1859. He left at age 20 and for three decades thereafter, showing a preference for the countryside, he criss-crossed the British colonies of the Indian Ocean world. MANCHESTER LIBRARIES, INFORMATION AND ARCHIVES, MANCHESTER CITY COUNCIL

Back Mill Street was one of the haunts of John Brown. The son of an Ancoats pharmacist, by 1888 Brown was in Kimberley, working the roads as a highwayman robbing African migrants of their wages. Brown re-joined McLoughlin’s gang, in Johannesburg, in the early 1890s. MANCHESTER LIBRARIES, INFORMATION AND ARCHIVES, MANCHESTER CITY COUNCIL

Withington Workhouse, where McLoughlin’s mother, Eliza, said to be suffering from ‘senility’, died a pauper at the age of 50. During World War I, the buildings were used to house German prisoners of war, offering a further illustration of how the architecture of certain institutions in early industrial Manchester manifested socially repressive features. MANCHESTER LIBRARIES, INFORMATION AND ARCHIVES, MANCHESTER CITY COUNCIL

Charles Peace, picaresque Midlands burglar, folk-hero and murderer, jumped from a moving train in a failed attempt to elude the police in Worksop, in 1879. It was a feat that McLoughlin emulated successfully on the Witwatersrand 15 years later, in 1894. SHEFFIELD ARCHIVES

A blacksmith’s apprentice and contemporary of McLoughlin’s, Bob Horridge was an innovative burglar who became an underworld hero when his gang successfully removed a safe holding the payroll from a textile mill in Bradford in 1878.

Up Great Ancoats Street, on Shudehill, the Smithfield Market and its surrounds were central to Jack McLoughlin and his mother, Eliza, who in 1878 was found guilty of receiving stolen goods from her sons. MANCHESTER LIBRARIES, INFORMATION AND ARCHIVES, MANCHESTER CITY COUNCIL

The Seven Stars was one of two public houses bearing the same name frequented by Jack McLoughlin and his brothers, William and Tommy, in the 1870s. On being sentenced to death McLoughlin expressed his regret at not being able to revisit the pub or the River Mersey. MANCHESTER LIBRARIES, INFORMATION AND ARCHIVES, MANCHESTER CITY COUNCIL

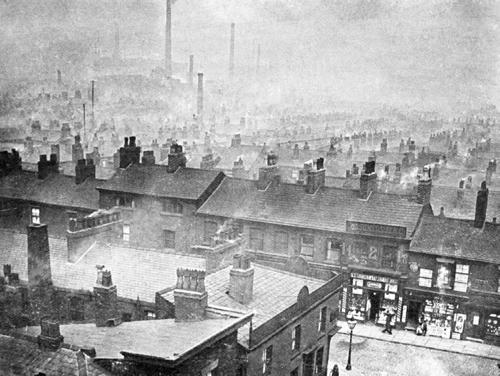

HMS Albatross. In 1880-81, a journey across the world aboard this Royal Navy sloop took 21-year-old McLoughlin from Plymouth to Singapore. It marked him as a sailor and placed him within reach of the frontier life and real-life heroes he craved. HAMPSHIRE RECORD OFFICE

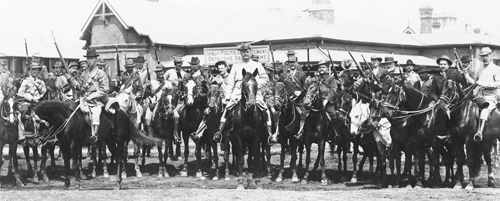

Outside Eureka City, on the way to more settled Barberton. The narrowing of the road at Elephant’s Creek was a site favoured by Irish Brigade highwaymen in the late 1880s. NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SOUTH AFRICA

For those with a passion for fighting, gambling and the horses – which was most of them – race days at the Eureka City racecourse held an irresistible attraction. The Victoria Hotel, half-way along the three-furlong racecourse, became an obvious meeting place for the Irish en route to yet more mayhem in Delagoa Bay. BARBERTON MUSEUM

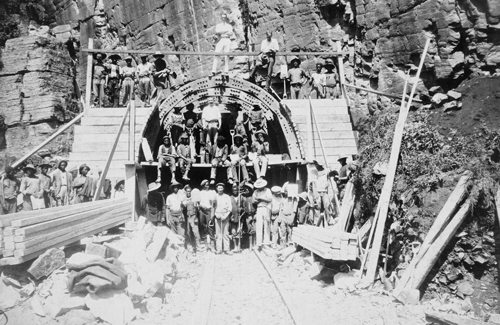

The earliest stretches of the Delagoa Bay–Pretoria railway line, completed in 1895, were built by African workers and teams of American, English and Irish navvies. Amongst the latter were the Irishmen who overran a Portuguese gunboat in the harbour at Lourenço Marques in 1887. MUSEUM AFRICA

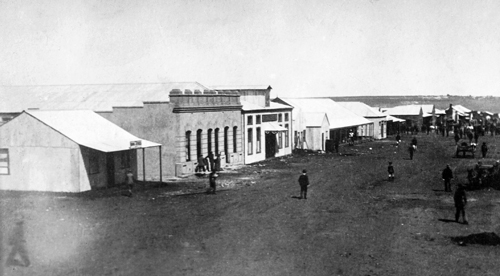

Commissioner Street, Johannesburg, in 1887, 1889 and 1890. The western end was dominated by gangsters linked to the ‘American Club’ and ‘Irish Brigade’. McLoughlin saw it as ‘one of the most dangerous places in Johannesburg’ and in 1897 it was the site of a gangland shootout so violent that even the police avoided it. MUSEUM AFRICA

The Goldfields coach deposited McLoughlin outside the Royal Hotel in Potchefstroom in mid-June 1890. After robbing a priest, he organised an Irish Brigade gaol break-out which cost one man his life and left his own wrist so badly shattered by a bullet that the lower part of his arm had to be amputated. MUSEUM AFRICA

Fleeing a depression in Johannesburg, McLoughlin’s gang were active in the countryside during the winter of 1890, robbing a mail coach and a store, and removing the Landdrost’s safe from this government building in Rustenburg. MUSEUM AFRICA

McLoughlin encountered FR Gill at the Krugersdorp Railway Station in the early 1890s while boarding trains without a valid ticket. It was Gill’s attempt to capture him that prompted ‘One-armed Jack’ to leap from a moving train, in 1894, and that later earned Gill a place on the gangster’s ‘death list’. NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SOUTH AFRICA

Edinburgh-trained Dr John van Niekerk was resident surgeon at the Johannesburg Hospital and the doctor who amputated McLoughlin’s arm in 1890. He also attended to the dying George Stevenson in 1895. SOUTH AFRICAN MEDICAL JOURNAL

The Hospital Matron, Mother Adele of the Order of the Holy Family, was responsible for nursing McLoughlin back to health after the amputation of his arm. SOUTH AFRICAN MEDICAL JOURNAL

Johannesburg General Hospital, 1893. McLoughlin, ashamed at having robbed a priest and uncomfortable in the presence of nuns, was unwilling to enter the hospital and in 1894 asked his brother, Tommy, to meet him in the grounds. SOUTH AFRICAN MEDICAL JOURNAL

Front entrance, Visagie Street Prison, Pretoria. In 1891, an unsuccessful attempt was made to storm the gaol and free two highwaymen on death row, Jack McLoughlin and several other Irishmen. The breakout was foiled by members of the State Artillery including Constable MJ de Beer. In 1909, De Beer was sent to Australia to identify McLoughlin and escort him back to South Africa. NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SOUTH AFRICA

Loreto Convent, Pretoria. In 1891, gangsters used a wooded section of its grounds to launch an unsuccessful attack on the adjacent Visagie Street Gaol. NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SOUTH AFRICA

Thomas Menton, an Irish deserter from the British Army and later jailer at Barberton and in Johannesburg, supported pleas for remissions of sentence by members of the McLoughlin gang. NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SOUTH AFRICA

The Johannesburg Prison and its ramshackle predecessors saw repeated and sometimes successful attempts at escape by various Irish inmates, including Jack McLoughlin and members of his gang during the early 1890s. MUSEUM AFRICA

The Old Vienna Café, corner of Market and Joubert Streets, where, over tea on a Saturday afternoon in 1895, Jack McLoughlin met Harry Lobb and told him that he intended shooting George Stevenson by sunset. THE STAR, BARNETT COLLECTION

Kerk Street Mosque. Eighteen-year-old Joseph Carr, known within the Muslim community as Hadji Mustaffa, was on the corner of Main and Wolhuter streets, on his way to prayers, when he was fatally shot by Jack McLoughlin. MUSEUM AFRICA

A view of Johannesburg from the Robinson Mine, where McLoughlin hid after the shooting. MUSEUM AFRICA

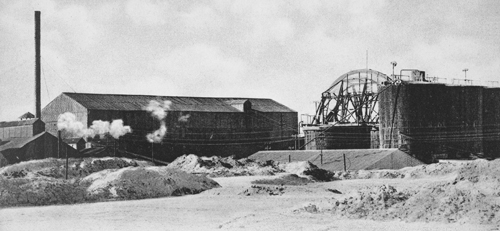

The Champ D’Or Mine job was McLoughlin’s parting shot: the takings would fund his escape into the vastness of the Indian Ocean rim. MUSEUM AFRICA

Fred de Wit Tossel, chief of mounted police, was responsible for arresting the Krugersdorp bank robbers in 1889 and investigating the McLoughlin gang’s Champ D’Or Mine heist in 1895. ‘Tossel’ was the assumed name of a man who was himself in some trouble with the British Army.

At Pentridge Gaol the day before his execution in 1880, Ned Kelly was a hero to many Australians and to several men of Irish extraction on the southern African highveld, including Jack McLoughlin and, more especially, Jack McKeone. UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE ARCHIVES

Aaron Sherritt allegedly betrayed members of Ned Kelly’s gang to the police. In 1880, newly married and under police protection, he was shot by his closest friend, Joe Byrne.

Joe Byrne, like McLoughlin much later, executed a police informer in the doorway of his residence after sending him advance warning that he was about to be shot.

Andrew Scott, ‘Captain Moonlite’, was a gay bush ranger whose gang members decorated their horses with pink ribbons. He was captured at WaggaWagga in 1879. John Hutchings, bandit leader in southern Africa in 1887‒88, took ‘Captain Moonlite’ as his nom de guerre some months before Jack McLoughlin assumed leadership of the gang on the Witwatersrand. STATE LIBRARY OF VICTORIA PICTURES COLLECTION

James Nesbitt. Andrew Scott wore a ring made from a lock of Nesbitt’s hair and before being executed said, ‘My dying wish is to be buried besides my beloved.’ Scott’s last wish was fulfilled in January 1995 when his bones were exhumed and re-interred with those of Nesbitt. STATE LIBRARY OF VICTORIA PICTURES COLLECTION

In 1900, while making his way across the Cook Strait, from Wellington to Lyttleton, McLoughlin unsuccessfully stowed away on the SS Rotomahana. CLYDE BUILT SHIPS

The muffled sound of an explosion was heard from the small cottage at far right when the McLoughlin gang blasted the safe in the offices of the Moree Railway Station. It was one of three such attacks on small town railway stations in rural New South Wales in 1902. NEW SOUTH WALES STATE RECORDS

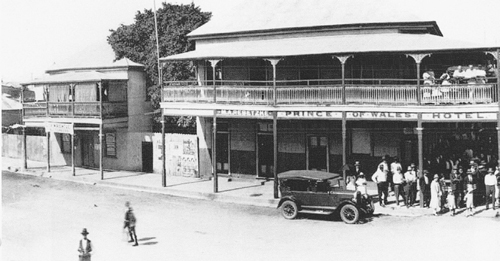

The Prince of Wales Hotel, Mackay, Queensland, site of McLoughlin’s last criminal act in Australia in 1906 – the theft of a gold watch and chain. He was sentenced to three years’ hard labour in the ‘Hell Hole of the Pacific’ – the island prison off Brisbane. NEW SOUTH WALES STATE RECORDS

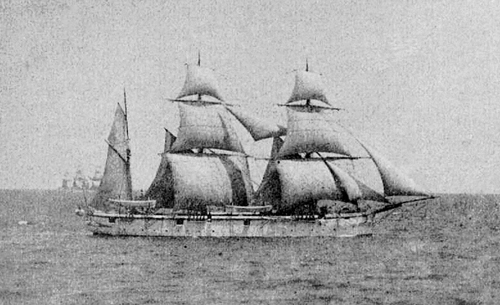

The SS Waratah taking on cargo in Port Adelaide, shortly before it was joined by three men bound for Natal whose names were discreetly left off the official passenger list – Jack McLoughlin and officers De Beer and Mynott. After they had disembarked in Durban, in July 1909, the ship went missing in one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of the Southern Ocean. STATE LIBRARY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA

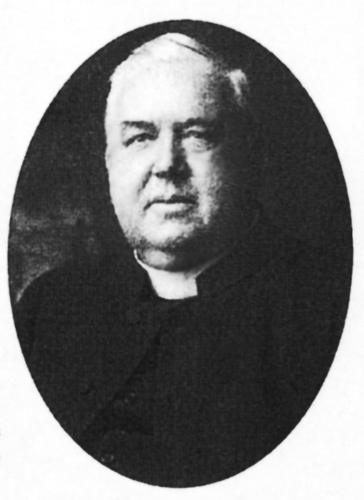

Father Thomas Ryan, OMI, an Irish priest with extensive experience in working-class communities in Australia, England and continental Europe; also a personal friend of General JC Smuts, Acting Minister of Justice. He was called upon to counsel and comfort Jack McLoughlin during his final hours in 1910. OBLATE COLLECTION, MULGRAVE

A Sunday Times artist captured Jack McLoughlin, seated at an angle in the dock so as to conceal his missing right arm, at his trial in Johannesburg, in December 1909. SUNDAY TIMES

George Stevenson, the boxer-gangster and object of McLoughlin’s infatuation before he turned police informer. The sketch, from a photograph of Stevenson, was made for the Sunday Times at the time of McLoughlin’s trial, 14 years after the shooting. SUNDAY TIMES

Sir James Rose Innes, Chief Justice and servant of empire, presided over McLoughlin’s trial, which was finalised before the coming of the Union in 1910. NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SOUTH AFRICA

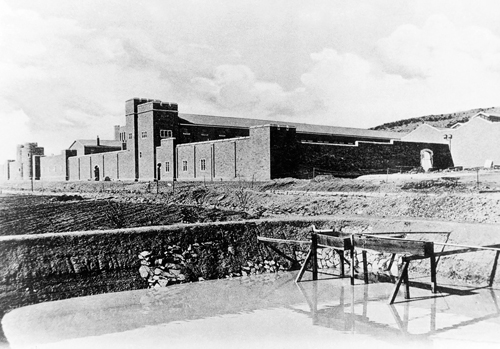

Jack McLoughlin was hanged at the recently opened Pretoria Central Prison on 10 January 1910. He was among the first 10 white men to be executed at a prison which gained steadily in notoriety in the long twentieth century.NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF SOUTH AFRICA