THREE MONTHS. THREE months. THREE MONTHS to find Morton’s parents, or lose Morton himself.

This thought rubbed like a blister against Olive’s other thoughts as she struggled through the second day of junior high. She managed to arrive at school in actual pants this time, which was a considerable improvement. However, the pants had a mysterious pinkish blotch on the seat, which might have been caused by a laundry mishap, a unique form of mold, or the puddle of Sugar Puffy Kitten Bits that Olive had sat on after accidentally spilling cereal all over the breakfast table that morning. Olive was pleasantly unaware of the blotch’s presence until math class, when she was called up to the board to solve a problem and the class erupted into sniggers behind her.

By the time the last hour of the day arrived, Olive barely had the energy to climb the worn stone stairs to the art room and pull out her stool at the table all the way at the back.

Once again, the art teacher was nowhere to be seen. The students sat at their tables, chattering and squirming and complaining. But as the bell rang and the minutes ticked by, a sense of not-right-ness settled gradually over the room. Stools stopped squeaking. Fingers stopped fidgeting. Students glanced at each other in puzzled silence. Soon the class had gotten so quiet that a soft whistling sound from the back of the room seemed to echo through the air.

Looking for the source of the sound, the other students turned around and stared directly at Olive. Olive, feeling twenty-five pairs of eyes on her, turned around as well. There was nothing behind her but a high white wall. She stared at the wall for a while, pretending that it was the most fascinating thing she’d seen all day. And, as she stared at the wall, something red and curly caught the corner of her eye. Olive glanced down. There, on the floor, with her kinks of dark red hair spread out against the tiles, lay Ms. Teedlebaum. The whistling sound was coming from her nose.

“Ms. Teedlebaum?” whispered Olive. “Are you awake?”

“Unfortunately, yes,” said Ms. Teedlebaum. “Would you help me up, please?” Eyes still shut, Ms. Teedlebaum reached out two arms that were covered in clanking rows of bangle bracelets. Olive took Ms. Teedlebaum’s hands. The other students watched as the art teacher hefted herself back onto her feet, almost yanking Olive off of hers in the process. Then Ms. Teedlebaum shuffled toward the front of the classroom, pressing both hands to the small of her back and hunching over so that the cords and whistles and lanyards around her neck had an extra-wide range in which to swing.

“I have an old back injury that’s acting up today. Circus stuff,” said Ms. Teedlebaum, as though this required no further explanation. “You won’t mind if I teach lying down today, will you?”

No one answered.

“Good,” said Ms. Teedlebaum. With a heavy sigh, she lay down flat on her back on the large table at the front of the art room, turning her face toward the ceiling and closing her eyes.

“We are going to continue our study of portraits for the next two weeks,” said Ms. Teedlebaum to the ceiling. “Today, you’ll work on your self-portraits. I’ve labeled your shelves in the cabinet, so you can find your pictures. You know where the other materials are.” Here several students gave each other confused looks, but Ms. Teedlebaum, with her eyes closed, didn’t notice. “Your assignment for tomorrow is to bring in a photograph. It can be of one person or a group of people, but it has to be people. No dogs or cats or unicorns or what-have-you. You’re going to work from the photograph to paint the portrait, so make sure it’s a nice clear picture. Any questions?” Ms. Teedlebaum asked this without opening her eyes, so it was a good thing that no one raised a hand. “Okay. Get to work.”

Ms. Teedlebaum lay motionless on the front table while the students dug through the cabinets to find their unfinished portraits and art materials. It was hard to tell if Ms. Teedlebaum was, in fact, still awake, but by some unspoken agreement everyone tiptoed and whispered, just in case. Olive slipped down from her stool once all the other students were out of the way and brought her self-portrait back to her desk.

She gave the picture a long look. It was both better and worse than she remembered. The shape of her face wasn’t too lumpy or off-balance, although her nose looked as though it began in the center of her forehead, and her eyes were either too far apart or too close together—it was hard to tell which. Maybe this was because the eyes were so large overall. Olive picked up her eraser and started rubbing.

While she smudged away the upper end of the nose, she thought about the homework assignment. What picture should she bring in? Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody were the picture-takers in the Dunwoody house, so most of the pictures in the family albums were of Olive. In fact, if you flipped quickly through the pages of each album, you could watch Olive gradually shrinking or swelling, depending on which direction you flipped.

There were some pictures of Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody by themselves, taken before Olive had been born—like the one that sat on Mr. Dunwoody’s desk, where Alec and Alice beamed at each other in the center of a dance floor, with romantic lights glinting off the thick lenses of their glasses. Neither of her parents was facing the camera, and the glints on their glasses would be tricky to capture.

Olive chewed the inside of her cheek, thinking. What she really needed was a traditional family photo, the kind that people posed for in photographers’ studios, where everyone is smiling and looking slightly to the right. She had seen a photograph just like this, not long ago…

Inside Olive’s mind, a flurry of snowflakes began to glitter and spin like the tiny white shards in a snow globe. When they came to rest at last, Olive could see that they weren’t snowflakes at all, but fragments of paper—fragments that had arranged themselves to spell out something new. Something wonderful. Something that meant she might need a lot less than three months to get Morton’s parents back.

For the rest of art class, both Ms. Teedlebaum and Olive remained motionless, one with her eyes shut, one staring straight ahead, neither one seeing anything at all.

The final bell jolted Olive out of her daydreams. Ms. Teedlebaum, on the other hand, didn’t even seem to hear it. The art teacher stayed flat on her back on the table as the students put their materials away on the shelves, picked up their book bags, and dashed out the door. Olive waited until the other kids were gone before wandering toward the cabinets. She looked along the shelves for her place, the spot labeled with a little strip of tape that read Olive Dunwoody. But as she slid her portrait onto the shelf, she heard the rustle of a sheet of paper. There was something else in Olive’s spot.

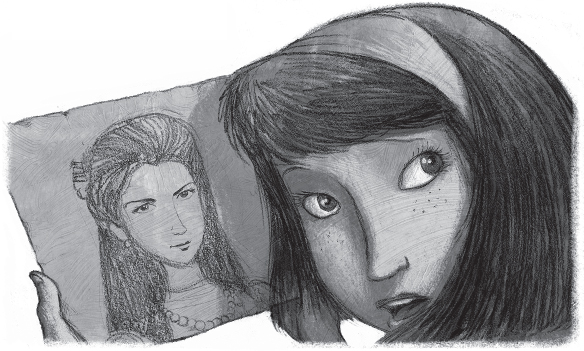

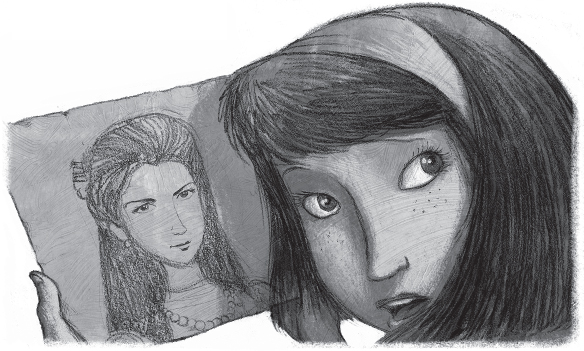

Olive pulled the paper down from the cabinet shelf. It felt thick and brittle at the same time, with soft, battered edges and yellowed corners. On the paper was a portrait, done skillfully in fine black pencil. It was the portrait of a young woman. A young woman with delicate features, long-lashed eyes, and a tiny, chilly mouth. A woman with thick, dark hair—and, nearly out of sight, at the very bottom of the paper, a glistening string of pearls.

The world around Olive became a blur. Her ears filled with a muted roaring sound, as though she’d been underwater in a deep black lake for too long. She couldn’t even hear Ms. Teedlebaum sighing behind her, or the table creaking as the art teacher stood up and shuffled toward her desk. The paper trembled in Olive’s hands.

“Um…Ms. Teedlebaum…?” she croaked.

A jingling sound drifted through the watery roar. “Olive,” said Ms. Teedlebaum, leaning over Olive’s shoulder, “did you draw that?”

“No,” whispered Olive. “I just found it on my shelf. I didn’t—I didn’t—”

“Well, it’s very good.” Ms. Teedlebaum craned closer. A knot of keys and pens smacked Olive in the back of the head. “Of course, if it were your self-portrait, it wouldn’t be very good, because it looks nothing like you. But on its own—that’s the work of an artist.”

“Mm-hmm,” said Olive weakly.

“You said you found it on your shelf?” asked Ms. Teedlebaum. “Should I pass it around the classroom tomorrow and see who it belongs to?”

Olive jolted out of her blur. “NO,” she said. She turned to face Ms. Teedlebaum, clutching the paper against her chest. “I mean…it’s mine. I just didn’t draw it. But it belongs to me.” She swallowed. “It came from my house.”

Ms. Teedlebaum’s eyes had already glazed over. “I forgot to tell the first class to bring bicycle tires tomorrow,” she sighed, gazing over Olive’s head. “Shoot.” With another sigh, the art teacher headed back toward her desk.

“Um—Ms. Teedlebaum?” Olive asked, trying to squish the shakiness out of her voice. “Do you…do you know if anyone else has been in here? In this room?”

Ms. Teedlebaum glanced up from behind a mound of clutter on her desk. The kinks of her hair bounced. “In here?” She looked around the room blankly.

“…Besides the other students, I mean.”

“Oh, yes!” Ms. Teedlebaum smiled. “The other students. Yes.”

“But has there been anyone else? Like…could any other grown-ups get in here?”

“Well, the janitor comes in every evening, but he doesn’t stay long,” said Ms. Teedlebaum, rearranging the mound of clutter into a few smaller cluttery mounds. “He really just sweeps the floor these days. He says he’s afraid of putting something that might actually be art in the trash again. Hey!” Ms. Teedlebaum crowed. “I’ve got three bicycle tires right here!”

As Ms. Teedlebaum happily unearthed the bicycle tires, Olive looked back down at the paper in her hands. Annabelle’s lifeless eyes gazed up at her. Even in black and white, their stare made Olive’s skin break out in goose bumps. To escape their gaze, Olive flipped the paper over—and saw, with a horrible, prickling chill, that something was written on the back.

Oh, Olive, read the paper, in fine, ladylike cursive,

I can’t tell you how dull it has been, watching you bumble through the end of the summer, trespassing on our family’s property, while I was forced to remain outside. But I knew you couldn’t stay indoors forever. I may not be able to get inside your house—my house, that is—but I can reach you anywhere else, at any time I choose. Remember that.

Yes, I’ve been watching you. And I know what you are about to attempt. Here is my only advice: Do not waste this opportunity, Olive. You don’t have much time left, and you may never get this chance again.

Of course, I don’t expect you to heed my words. It’s hard to know whom to trust, isn’t it? Should you do what I say, or the opposite? Can you trust your own closest friends? I believed that I could trust Lucinda—it was she who kept Grandfather’s sketch of me safe inside of her house for all these years—and yet in the end she proved to be unworthy. Take a careful look at those you trust, Olive. Because your own friend is hiding a rather large secret from you.

Good luck, Olive Dunwoody.

—Annabelle