AN UNEVEN MARCH TOWARD EQUALITY IN EUROPE

I’d like to return to the question of the historical development of inequality. France is one of the countries for which we have the most reliable historical data on income and, more particularly, on wealth and property ownership. This is owing to the system for recording inheritances and estates established at the time of the French Revolution, which has resulted in inheritance archives with unusually rich data going back to the late eighteenth century (fig. 5 and 6).

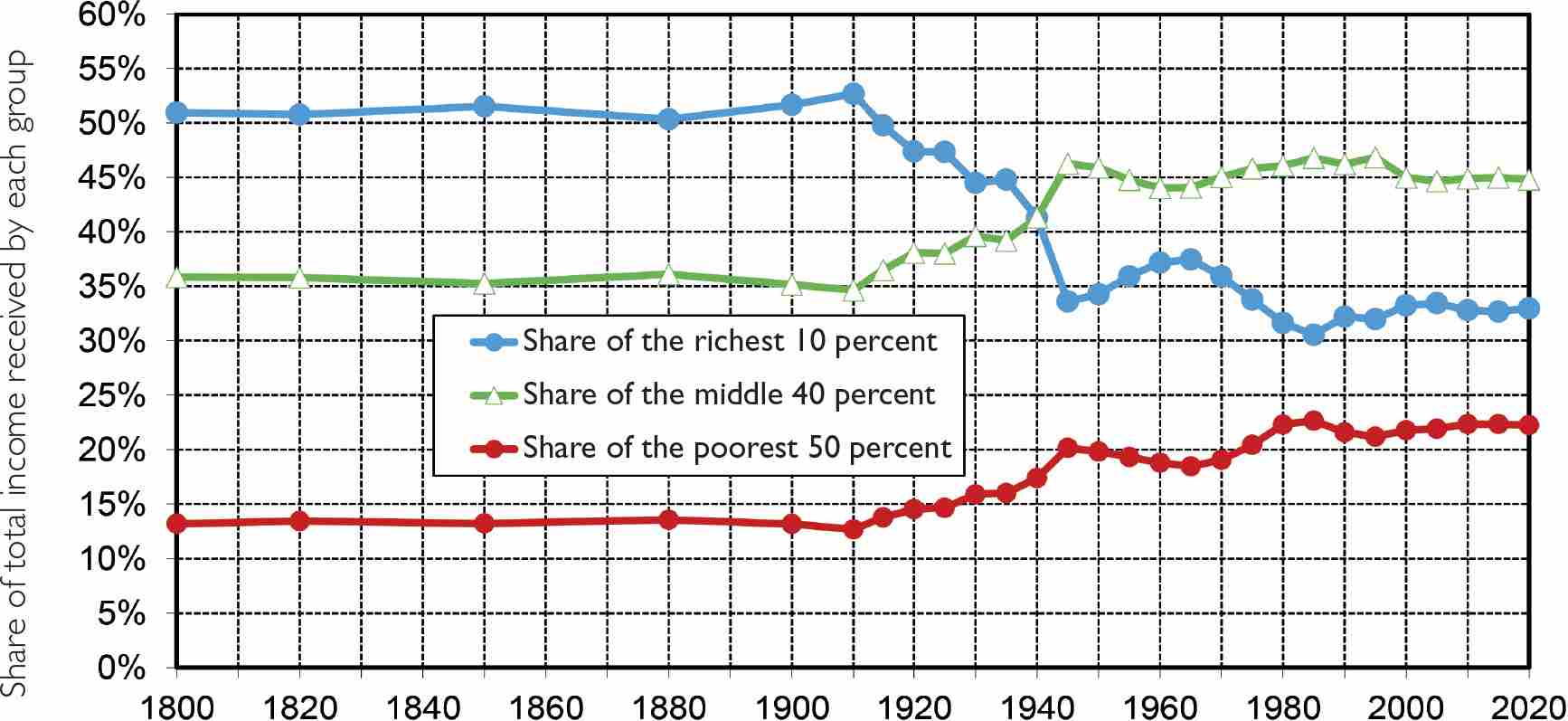

Thus, when it comes to income, we do see a movement toward greater equality in the last two centuries, especially in the twentieth. The share of income going to the richest 10 percent declined from 50 percent to 30 or 35 percent, while the share going to the poorest 50 percent rose from 10 or 15 percent to 20 or 25 percent. Yet the size of this change should be kept in perspective. The share going to the poorest 50 percent, as we’ve seen, is still well below the share going to the richest 10 percent, even though the poorest 50 percent are by definition five times as numerous.

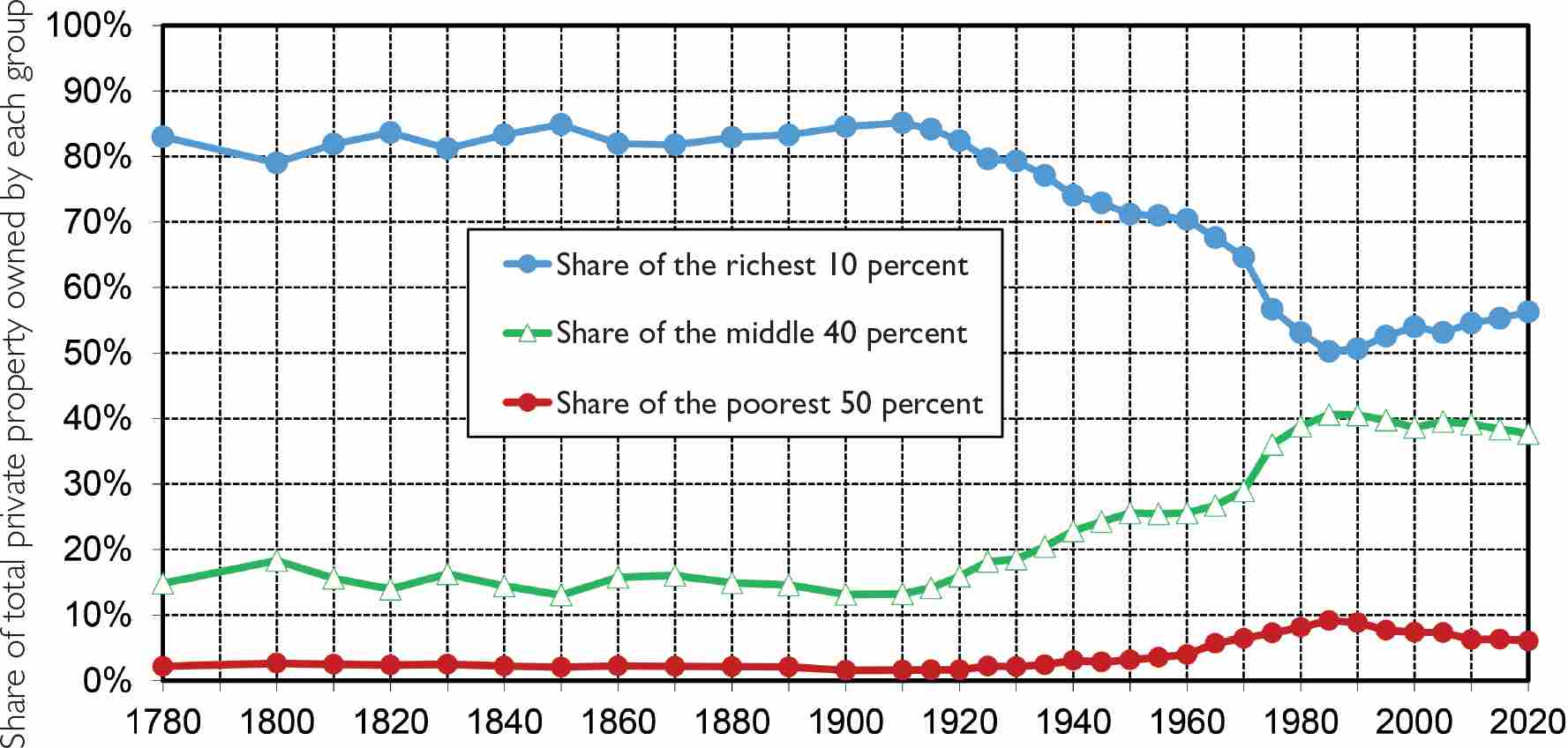

The level of inequality is much greater when we look at the distribution of property, and the movement toward equality there is much more limited. We do observe a significant reduction in the share of total property belonging to the richest 10 percent, which drops from 80 or 90 percent on the eve of World War I to 50 or 60 percent today, but that share has started to rise again since the 1980s. So while it’s important to recognize the long-term drop, we shouldn’t exaggerate its size. Furthermore, this reduction has basically benefited the next 40 percent, those falling between the richest 10 percent and the poorest 50 percent. But the poorest 50 percent have hardly benefited from the redistribution of property in the past two centuries at all.

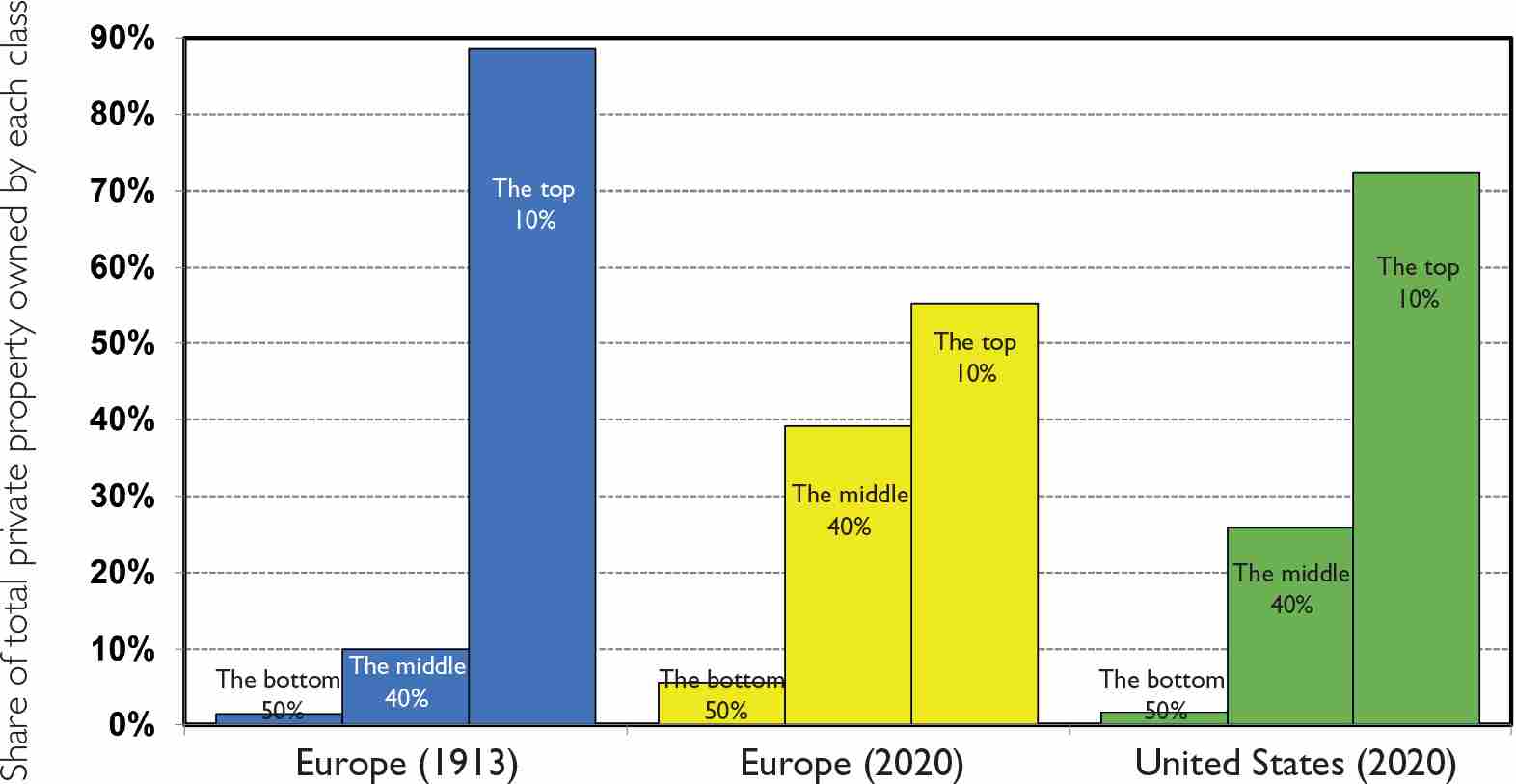

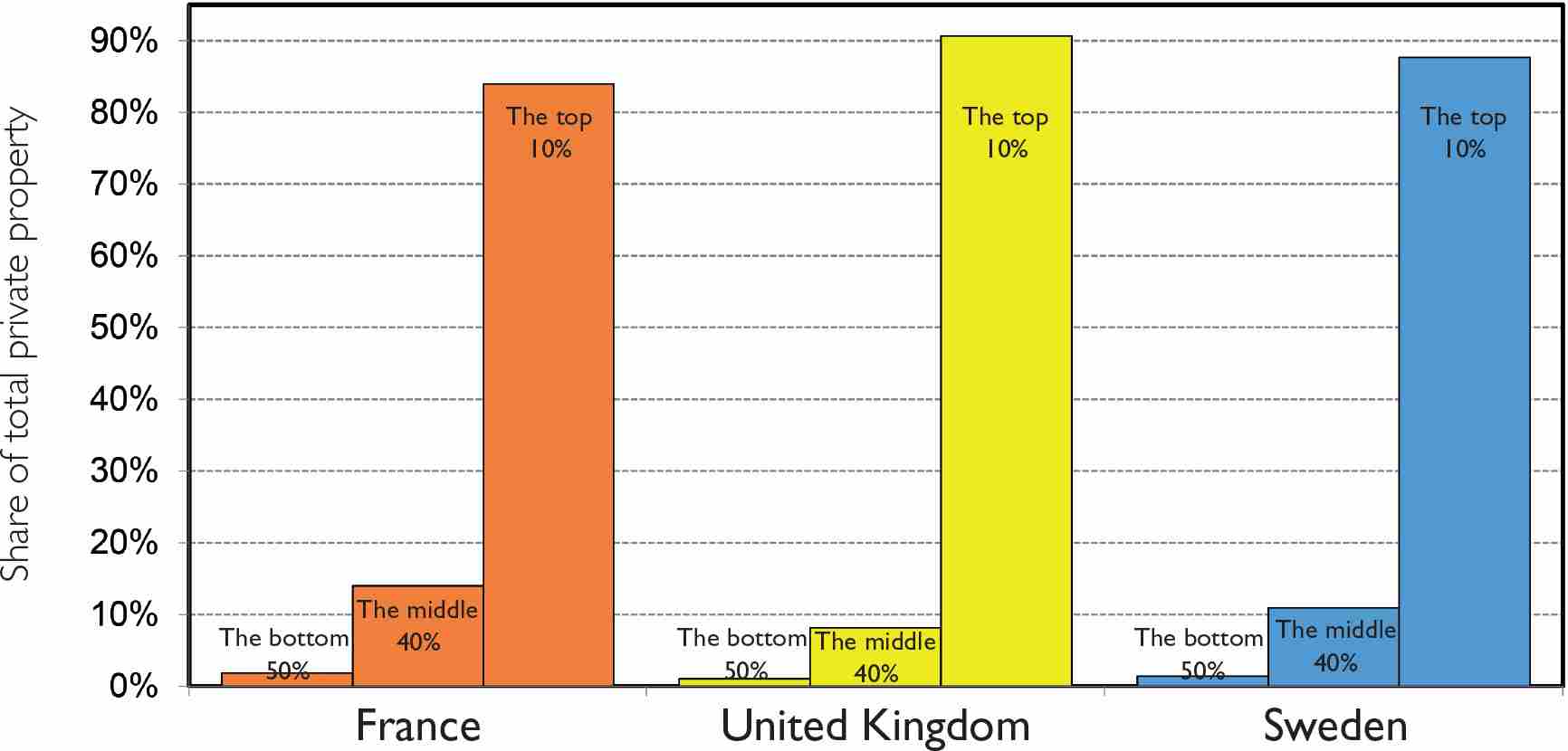

In Western Europe (Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Sweden), the overall trends have been quite similar: between 1913 and 1920, there was a shift toward a slightly less extreme concentration of wealth (fig. 7 and 8). The novel development was the emergence of what I have called the property-owning middle class. These 40 percent, who are neither the richest 10 percent nor the poorest 50 percent, owned practically nothing until 1913 and were thus almost as poor as the poorest 50 percent. There had been no middle class. Today, this group owns 40 percent of the total wealth of Western Europe and represents 40 percent of the total population: its average wealth is on the order of 200,000 euros per adult. The median in these households is 100,000 euros per adult, but the households may possess 100,000, 200,000, 300,000, or 400,000 euros. These are people who are not enormously wealthy but who are far from being truly poor and who resent being treated as such. The emergence of this group is a considerable event—economically, socially, and politically—even if access to wealth remains practically nil for the poorest 50 percent.

FIG. 5 Distribution of income in France, 1800–2020: The start of a long-term movement toward equality?

The share of total income going to the top 10 percent of earners, including income from work (salaries and wages, income from nonsalaried activities, retirement pensions, unemployment compensation) and income from capital (profits, dividends, interest, rent, capital gains, etc.) stood at around 50 percent from 1800 to 1910. After the two world wars, the income gap lessened, benefiting both the working class (the poorest 50 percent) and the middle class (the middle 40 percent), to the detriment of the upper class (the richest 10 percent). See: piketty.pse.ens.fr/egalite

FIG. 6 The distribution of property in France, 1780–2020: The gradual emergence of a propertied middle class

The share of total private property going to the richest 10 percent (including real estate, business assets, and financial assets, net of debt) hovered at 80 to 90 percent in France from 1780 to 1910. Property ownership became more widespread in the wake of World War I, a trend that stopped in the early 1980s and primarily benefited the “propertied middle class,” defined here as the group between the disadvantaged classes (the poorest 50 percent) and the well to do (the richest 10 percent). See: piketty.pse.ens.fr/egalite

FIG. 7 The persistence of highly concentrated property ownership

The share of total private property owned by the richest 10 percent in Europe in 1913 (averaged for France, the United Kingdom, and Sweden) came to 89 percent (with the poorest 50 percent owning just 1 percent); 56 percent in Europe in 2020 (with the poorest 50 percent owning 6 percent); and 72 percent in the United States in 2020 (with the poorest 50 percent owning 2 percent). See: piketty.pse.ens.fr/egalite

FIG. 8 Extreme inequality of wealth: European property-owner societies in the Belle Epoque (1880–1914)

The share going to the wealthiest 10 percent (counting real estate, business assets, and financial assets, minus any debt) averaged 84 percent in France from 1880 to 1914 (as against 14 percent to the middle 40 percent, and 2 percent to the poorest 50 percent); 91 percent in the United Kingdom (as against 8 percent and 1 percent); and 88 percent in Sweden (as against 11 percent and 1 percent). See: piketty.pse.ens.fr/egalite

In Europe, the main characteristics are a persistent high concentration of property and the emergence of a property-owning middle class. What we see in the United States today is intermediate between the present state in Europe and its situation before World War I. The propertied middle class in the United States is shrinking, and whereas it once reached the European levels of 30 to 40 years ago, it is starting to drop closer to Europe’s pre–World War I levels.

In a general way, the history of inequality in the countries of Europe before World War I is full of useful instruction. The period was a very rich one in comparison with the present period, and it has had a profound effect on my trajectory as a researcher. My friends and colleagues Gilles Postel-Vinay and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal and I were able to show that the degree of property concentration in France differed little from its concentration in the United Kingdom. This is significant, because political speeches made during the French Third Republic constantly contrasted France and the United Kingdom. A major theme of France’s centrist elites—whether in politics, finance, or the republican movement—was the contention that “We are utterly different from the United Kingdom. Owing to the French Revolution, we are an egalitarian nation, and therefore we don’t have to create progressive income or inheritance taxes. That’s all very useful for a country as monarchical and highly inegalitarian as the United Kingdom, or as authoritarian as Prussia, but we French, who invented liberty and equality, are already a country of small landowners and have divided up our landed estates.” Certainly, except that property had not been divided much at all in the first place, and in the second, landed estates no longer had much significance in 1913. While it was true that land ownership was more concentrated in the United Kingdom, this was secondary to the fact that, with respect to industrial capital or financial portfolios, which were invested all over the world at that time, it made little difference to the accumulation and concentration of fortunes whether you were a republic or a monarchy. France and the United Kingdom had similarly high levels of concentrated wealth. I was thus able, a century after the fact, to reveal the hypocrisy of a good many of that era’s political speeches, including those of contemporary economists like Paul Leroy-Baulieu, who loudly insisted that France was a nation of small landowners.

The data, in fact, was starting to be put to use even at the time, because the inheritance tax had become slightly progressive in the wake of a 1901 law. This serves to show that a change in the institutional and fiscal system can free up information and make available a type of knowledge that can then be put to good use. For example, Joseph Caillaux was able to address the Chamber of Deputies and, using statistics on inheritance to support his claim, declare that France was not in fact a country of small landowners. The data was also used to create a tax on income in 1914, though its effect was muted given the new challenges the country then faced. France was practically the last Western country to enact an income tax. The majorities in the Senate and Chamber of Deputies that passed the law of July 15, 1914, did so not to invest in education but to finance the war against Germany. It was the one factor that could break the logjam, at a time when a progressive income tax had long existed in many Northern European countries, as well as in Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. That France was slow to sign on was partly due to its complacent belief in its own egalitarianism, based on the fact of the French Revolution.