THE RISE OF THE WELFARE STATE: EDUCATION SPENDING AS AN EXAMPLE

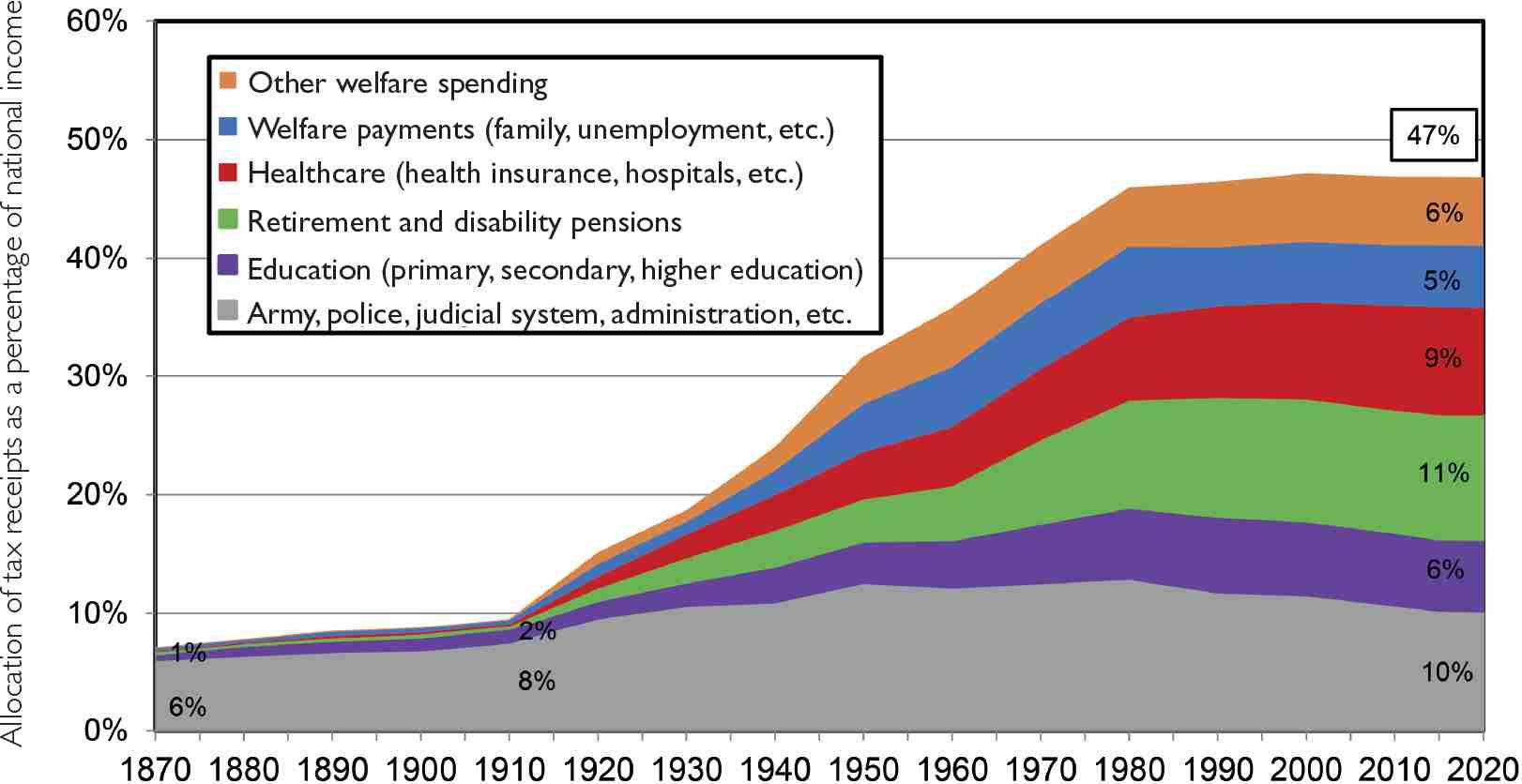

In Europe, one of the most important factors for understanding the trend toward equality in the twentieth century is the rise of the welfare state. Here again, while the circumstances in different countries varied, the development was quite widely shared throughout Western Europe (the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Sweden). Until World War I, the state’s total levy on national income was less than 10 percent, which it used mostly to maintain order, enforce property rights, pay the police force and courts, and develop capacity for foreign intervention, in keeping with colonial expansion. Expenses other than those used to assert the state’s authority were kept to a minimum. After 1918, a movement began that would lead to taxation on a much larger scale, and over the last thirty years, tax receipts for the four European nations mentioned above have remained stable at around 45 percent of national income (fig. 9).

Let’s look at education, which is undoubtedly one of the most important factors in bringing about equality. Over the past century, public spending on education has increased tenfold, measured as a percentage of national income. Before World War I, it represented less than 0.5 percent of national income: the system was extremely stratified, and only a small minority could continue their education past primary school. Yet even primary school was poorly funded compared to secondary school and university. Today, the average spending for education in our four Western European countries comes to 6 percent of national income.

This increase in education spending has been a factor in promoting individual freedom, equality, and prosperity, reducing levels of inequality, and raising productivity and living standards. We are so used to government funding for education that we sometimes forget that this substantial development played a central role in the limited but real progress toward equality that I mentioned earlier. But to qualify this statement somewhat, we should note that education spending has stagnated since the 1980s and 1990s, quite paradoxically, since access to higher education has increased during this period: while barely 20 percent of any age cohort went on to higher education in the 1980s, that figure has climbed to 60 percent today. In concrete terms, it means that the investment per student has declined. We’ve unfortunately seen this drop in per-student investment in France during the last fifteen years, especially in the least well-endowed fields of university study.

FIG. 9 The rise of the welfare state in Europe, 1870–2020

In 2020, the average total tax levy in Western Europe amounted to 47 percent of national income and was spent as follows: 10 percent of national income on state expenditures (army, police, judicial system, general administration, roads and other basic infrastructure, etc.); 6 percent on education; 11 percent on pensions; 9 percent on healthcare; 5 percent on social welfare benefits (excluding pensions); 6 percent on other welfare costs (housing, etc.). Before 1914, virtually all the money provided by taxation went to state expenditures. Source: See piketty.pse.ens.fr/egalite

This phenomenon—fairly paradoxical in nature and running counter to the developments of the past century—is rooted in a system of political beliefs that since the 1980s and 1990s has maintained that the overall level of public spending and taxation must absolutely be held steady with respect to national income. Given that the share going to healthcare and retirement benefits has been increasing—not enough to keep pace with the public’s needs, but increasing nonetheless—other spending has had to be reduced, and that’s what has happened with education over the long run. Expanding the size of the welfare state could remedy these contradictions, but it would call for new milestones in tax justice and progressive taxation, on both a national and an international level.

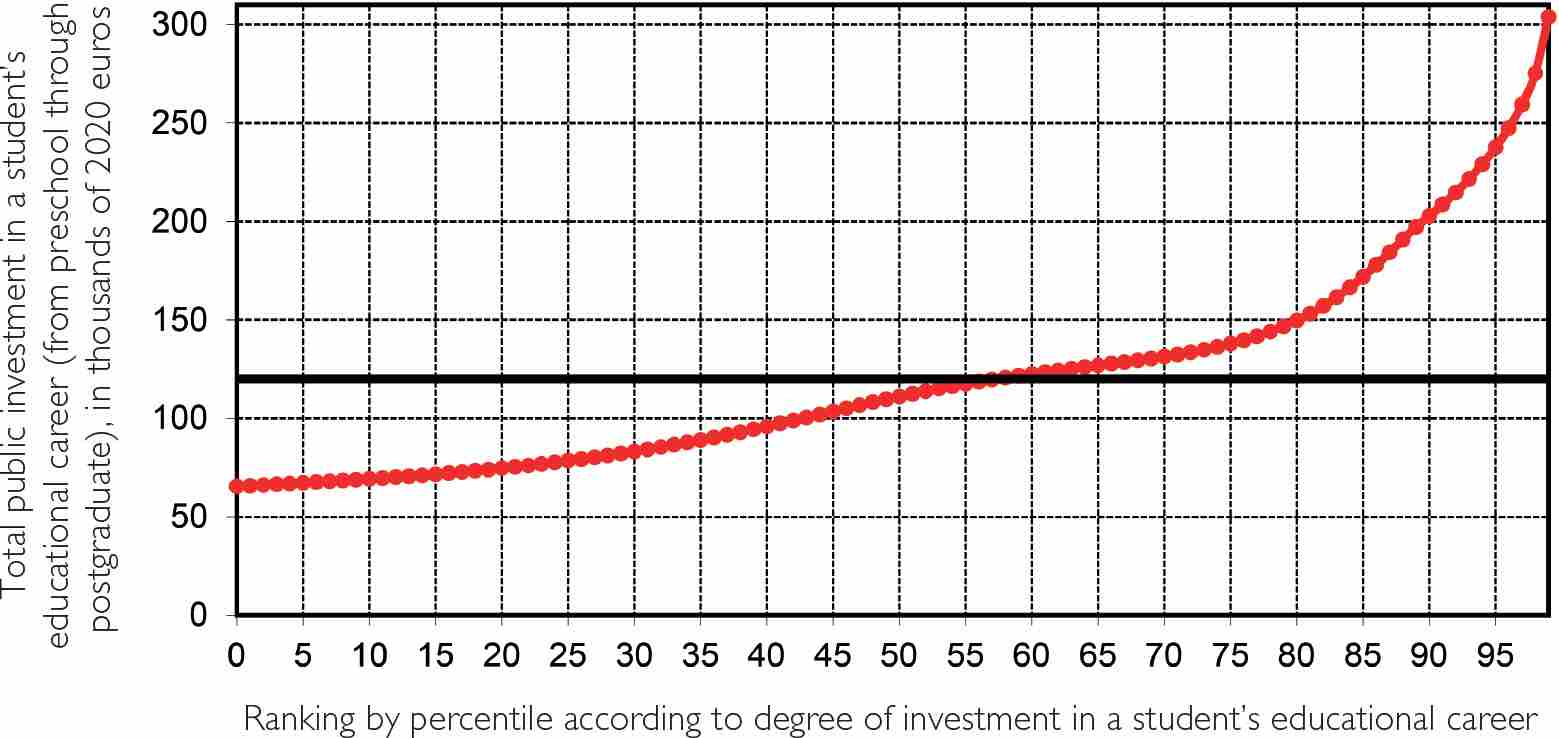

And while there has certainly been progress toward a more equal distribution of the public investment in education, we shouldn’t paint an idealized picture. Let’s look at the inequality of investment in education in France (fig. 10). This data applies to the generation that is completing its education today, young men and women who turned twenty in the year 2020. In the graph, all those born in 2000 are ranked according to the total education spending they’ve received from kindergarten through advanced degrees. Briefly, those who receive the most public funds for education—on the order of 250,000 to 300,000 euros each over the course of their educational career—are those who follow long and well-financed courses of study—typically preparatory programs that prepare students for the competitive-entry higher institutions known in France as the grandes écoles, and the grandes écoles themselves. Those represented on the graph at the lowest levels are the young men and women who left school at sixteen or seventeen: they received funding only for primary and secondary education. And those in the middle are the students who followed a poorly financed course of study at a university, such as a degree in humanities.

FIG. 10 The inequality of education investment in France

On average, students reaching age twenty in 2020 received (from preschool to postgraduate degree) 120,000 euros in public spending (approximately fifteen years of schooling, at an average cost of 8,000 euros per year). The 10 percent of students in this generation who benefited from the least public investment received 65,000–70,000 euros, while the 10 percent who benefited from the greatest investment received 200,000–300,000 euros. NB: the average cost per year in the French system from 2015–20 varied from 5,000–6,000 euros for preschool and primary education, 8,000–10,000 euros for secondary education, 9,000–10,000 euros for university, and 15,000–16,000 euros for the preparatory course for entry to the grandes écoles. See: piketty.pse.ens.fr/egalite

FIG. 11 Colonies for the colonizers: Inequalities in education spending in historical perspective

In Algeria in 1950, the 10 percent of students benefiting from the most public spending on primary, secondary, and higher education received 82 percent of total education funds. In comparison, the share going to the 10 percent benefiting most in France in 1910 was 38 percent, and, in France in 2020, 20 percent (which is still twice as high as their share of student numbers). See: piketty.pse.ens.fr/egalite

The individuals on whom the least was spent received 60,000 to 70,000 euros in education funds, while those on whom the most was spent received 250,000 or 300,000 euros, and those in the middle about 100,000 euros. Briefly, we see a disparity in public spending of 200,000 euros between those who received the least and those who received the most. Unfortunately, those who receive the most tend to come from a more privileged social setting than the others. Public spending therefore reinforces existing inequalities in quite a substantial way. This 200,000-euro differential is about the size of the average inheritance: it’s as if the most privileged classes receive an additional average inheritance, this one a gift to them from the public coffers.

In the long run, access to education has actually expanded, but with two important qualifications: the inequalities are still substantial, and spending is at a much lower level than even in the recent past. I always come back to this paradox: our societies are still extremely inegalitarian, yet thanks to political battles and historical developments, they have made progress toward greater equality. What I have shown about the distribution of income and wealth also applies to the distribution of education spending (fig. 11). Today, the 10 percent of a given age group who receive the most public funds for education receive just 20 percent of total education spending. It is still a very large number, because the bottom 50 percent receive only about 35 percent. If the curve seems egalitarian, it is actually extraordinarily inegalitarian, since the 10 percent who get the most funding will get only 1.5 times less than the bottom 50 percent, although the latter are five times more numerous: briefly, the per-person spending for the top 10 percent is three times higher.

While the situation may seem more egalitarian today than in 1910, it is only because the system back then was even more stratified than it is now. For most social classes other than the well-heeled bourgeoisie, education ended after primary school. The bourgeois classes, on the other hand, had access to a system of higher education where a university professor’s salary was many times that of a schoolteacher. The stratification of the education system led to much greater inequality than today, and the disparities were more marked.

In colonial societies, education was stratified to an even greater degree. Briefly, the top 10 percent, to take Algeria in the 1950s, were the children of the colonists, who accounted for a little more than 10 percent of the population. The rest, meaning the “Algerian Muslims,” as they were then called, made up 90 percent of the population. The system was completely segregated, just as it was in the southern United States until the 1960s, where there were separate schools for whites and Blacks. In Algeria, there were schools for the children of colonists and schools for the children of Algerian Muslims. If you examine the budgets of that period—I draw here on the excellent research on the history of colonial budgets by Denis Cogneau, one of my colleagues at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS)—it turns out that 80 percent of the total education budget went to the children of colonists, though they were only 10 percent of the population. Additionally, this spending drew on indirect taxes that fell mainly on the colonized. To reiterate, the colonial government was levying taxes on the whole population, the great majority of whom were colonized subjects, to finance a system that primarily benefited the colonists’ children.

Our current educational system, then, whether we compare it to the colonial era or to France in 1910, is more open and more egalitarian. But the long-term trend toward equality has not reached its end point. We could well set other, different goals for the distribution of our investment in education, instead of speechifying about it in abstract terms. Constructing a norm for social justice also requires constructing tools that will allow citizens to deliberate and assess what’s being done. When it comes to tax justice, for example, we have put a lot of time into developing a system that, with its notions of income, capital, tax rate, and tax schedule, allows us in theory to check up on the underlying norm of tax fairness. In the case of national education, we have a multicriteria system that doesn’t really allow us to check on what’s being done and in practice leads to the kinds of results I’ve described. Much could be improved.