It is a damned place, is Perkis Moor. Perched high on the spine of the country, there is little up there but sheep and the crows that feed upon the corpses of sheep fallen in gorges, trapped in gullies, tumbled down scree. The shepherds do a good enough job, but they do not enjoy their work and are happy to retire of a night to their huts of millstone grit and turfed rooves, brutal little boxes with small windows in hulking walls that seem as much defensive as simply shelters.

The wind blows across Perkis Moor; it is the only thing that wanders freely, for it is a damned place, and even ramblers show little inclination to labour across the broken, unhappy earth. Ask a local—which is to say, ask anyone who lives by the moor, for no one would claim to live upon it, only to sojourn briefly until they can return to a proper place, fit for decent souls—ask a local why the place feels so baleful, so full of mindless, lolling hatefulness, and they will tell you it is haunted. The spirits of five thousand pagan dead are trapped there, so they say, from a time before Constantine, from before Christ. A great battle, fought with weapons of wood and rough iron, took place there. The culmination of a war between nameless tribes, for unknown reasons, they met there and offered no quarter. Five thousand dead and the grass fed by gallons of their gore. A terrible thing that scarred the land itself, a festering wound that seeps spectral blood into the here and now still, after all these years.

The shepherds say sometimes at night they hear the cries in strange languages long lost from the throats of living men, the screams, the clash of weapons. The shepherds know better than to look out of the small windows in the hulking walls of their millstone grit huts on such cursed nights or storm-threatened days. What they may see can do them no good, and an immortal soul is worth far more than assuaging a moment’s curiosity.

The locals say no merchant travelling with his wares will cross the moor, not even in daytime, for fear of making poor progress and still being upon it when the sun dips below the distant horizon. Once, an itinerant tinker did, they say. He scoffed at the legend and set out upon the dreary sheep path with liquor in him when he really needed wit. The shepherds found him the next day, cold and dead by the path, staring up at the grey clouds, eyes and mouth open to gather the drizzle. All the rain in the world could not wash away that expression of terror, though, the outward signifier of an experience that froze his blood and stopped his heart.

The archaeologists say ‘Bollocks’ to all that. There isn’t a shred of empirical evidence that such a battle ever took place. They say that it’s a myth and the old tales of a great spectral battle fought periodically upon Perkis Moor are simply the product of bored people in a boring place making things up to entertain themselves. In this, they are largely correct.

But not entirely.

* * *

The tall, pale man in the black suit and walking boots caused a huge sensation amongst the locals of the Perkis Path Inn, which is to say they went a little quieter when he entered, nodded covertly at him to their drinking partners when his back was turned, and marvelled at his accent, which was as alien to them as Ancient Assyrian. That the accent was German says little for the cosmopolitan nature of the locals.

‘You’ll be wanting a room, then?’ The landlord leaned heavily upon the counter and glowered at the strange stranger, with his fancy spectacles and gloves. The locals didn’t hold with such fripperies; if the Good Lord intended one to be terribly myopic, then it was not given to man to correct this defect. Much better that man wander around tripping over things. He might fall down the stairs or use bleach for flour, but at least he wouldn’t die horribly in a graceless state.

The man removed the blue-tinted spectacles, and it became apparent to the landlord that they were intended to protect the man’s eyes from the glare of daylight. He himself had never seen the glare of daylight, but his grandfather had once told him that the sun was actually a fiercely radiant object in the sky and not merely one area of the permanent overcast that glowed slightly more strongly than the rest. In some distant, foreign places like Egypt or China or Barnoldswick, it was said that sometimes the cloud cleared away and you could see the sky above, and the sun, and—at night—bright objects that defied rational explanation. The landlord had always been of the opinion that his grandfather had been making a joke. As if such things might be in a godly world.

Looking at the stranger’s strikingly blue eyes, eyes that hinted at an incisive mind and a calloused soul, it occurred to the landlord that there might be many ungodly things in a godly world, after all.

‘I shall,’ said the man in his ungodly accent, removing his ungodly gloves, and casting an ungodly eye upon the regulars, who returned their attention to their dominoes rather than suffer it for longer than necessary. He turned and looked through the mullion window, the road beyond distorted by the bullseye panes and thereby rendered far more interesting than the reality. ‘The moor is in that direction, isn’t it?’

‘It is. Thinking of going for a walk there later?’

‘I was considering it.’

‘Don’t,’ said the landlord, with a great satisfaction that echoed around every local’s heart in the public bar.

‘You don’t want to go up there,’ said a drinker. ‘Not good to go on the moor if you don’t need to.’

‘Perhaps,’ said the stranger, ‘I need to.’

‘Don’t look much like a shepherd t’me,’ said a dominoes player, and there was much amusement at this bon mot, the merriest thing ever said within those walls since they were raised 234 years earlier.

‘Why?’ The stranger’s tone was neutral. ‘Is it haunted?’

The landlord leaned yet more heavily upon the counter. It would have groaned under the stress if it had been some profane, foreign wood, like Norwegian pine from a profane fittings showroom. But it was good English oak, and it was used to the meaty forearms of stout English yeomanry leaning heavily upon it.

‘What if it is?’

The cold blue eyes turned to regard him. ‘Tell me all about it.’ And he produced a good stout English ten-bob note, and all animosities were shortly forgotten.

* * *

The stranger left the tavern some hours later, a room for the night secured and the locals rendered glazed and garrulous by the application of a multitude of ten-bob notes and the ale thus purchased.

In truth, they had told him little he did not already know, but the investigation was not purely based upon what they said, but upon how they said it. They believed every word of it, that much was plain. Every word was, of course, nonsense, but they held those words with a fervent regard. Even the most aggressively masculine of them would not venture upon the moor at night without an excellent reason, and that intrigued and satisfied the stranger, who was Johannes Cabal,* a necromancer of some little infamy. This job description he left off the battered ledger the inn used as a guest book, instead entering ‘Gentleman scientist’. In a rational and well-ordered world, he would have been perfectly happy to write ‘Necromancer’, but the world was not rational, and little enough of it was in any sort of order of which he could approve. Had he used that word, he would likely have received sour looks, poor service, and a lynch party, and so he did not.

The landlord looked at the not entirely inaccurate substitute term and wrinkled his brow. ‘So what are you doing here?’ Clearly the locals didn’t hold with any of that newfangled science stuff like evolution or gravity.

‘My current interest is folklore and legends,’ replied Cabal. ‘The tales of the moor drew my attention. I am considering a monograph upon the subject.’

‘A monograph?’

‘A monograph, yes.’

They looked at one another, both men with secrets. Cabal’s was that he had no intention of writing a monograph. The landlord’s, that he had no idea what a monograph was.

* * *

Presently, Cabal left the inn to ‘go for a walk’ and ‘get a breath of fresh air’. These claims were true, as both were unavoidable. His main aim was to carry out an experiment that was esoteric in both field and morality, true, but he would have to walk to get to the location he had chosen for the experiment and would doubtless have to breathe one or more times en route.

Cabal wore a soft Homburg in a dark grey bearing a sedate curve, an unimposing pinch, and a small black feather in the band, the loss of which had surely not inconvenienced the bird from which it came in the slightest. His suit was dour, but hard-wearing, and his boots—as mentioned previously—eminently suitable for tramping around on rough terrains. He carried a Gladstone bag and a cane topped with a tarnished silver skull. If one maintained a mental image of how a gentleman scientist might conceivably appear, it would certainly have been along the lines of Cabal’s wardrobe.

He walked in a brisk line along the road that bordered Perkis Moor until he was safely out of sight of the pub, and then performed a sharp left-hand turn that took him directly onto it. There was not a great deal of daylight left, but that was all to plan.

He did not need to go far onto the moor itself, just up onto a ridge at its edge that he had noted on the Ordnance Survey map of the area. The area it overlooked was a natural arena, a wide, flat depression rising into the flat of the main part of the moor. A natural arena, or perhaps ‘theatre’ was a better term. The vast majority of sightings of the unusual happened in or near this area. The closeness of the road was perhaps the primary explanation for the place having the most witnesses. The closeness of the pub was often mooted as the primary explanation for the sightings themselves, perhaps unkindly.

Perhaps not. Having found himself a dry spot at the ridge’s edge to sit upon, Cabal wasted no time tying a length of rubber tubing around his bicep, flicked the skin of the inside of the elbow to bring up a vein, and injected himself there with a syringe he drew from a sterile metal cylinder he took from his bag. The syringe contained a rare and potent narcotic that might threaten addiction if overindulged. This was not a concern; Cabal did little enough for recreational purposes as it was, and even amongst these rare hobbies and pastimes, becoming a junkie came very low upon his list of life goals.

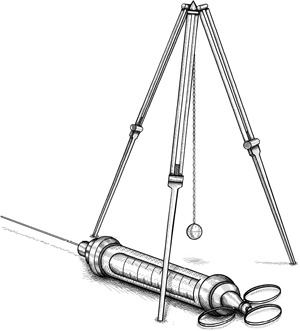

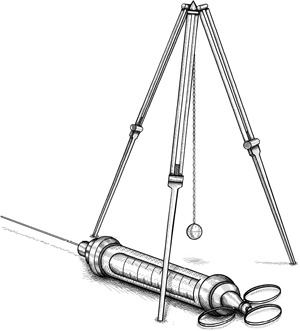

The act done, he loosened the tubing and placed it, the syringe, and its container back within the Gladstone bag. In their stead he removed a small tripod with telescoping legs and set it up by him. From its apex dangled a length of fine silver chain and upon its end a small silver sphere, its surface regularly pitted and a seam around its equator, where it might be unscrewed. Thus prepared, he relaxed and allowed himself to take in his surroundings, looking without seeing, hearing without listening.

The day died around him, and the night grew in its stead, unhurried and unheralded. Somewhere a lonely meadow pipit called. The sound was allowed into his ears and to merge with his awareness without him troubling to identify the bird, even down to naming it (Anthus pratensis) as was his usual wont. In the common run of things, this degree of mental slackness would have been impossible to him. It was the duty of the drug he had taken intravenously to render his mind less focussed, less capable, less analytical, or—to put it differently—more like those of normal people.

He relaxed as deeply as he was capable, a great deal more deeply than he might have managed without narcotic aid, and measured his breaths, focusing entirely on the steady metre of inhalation, exhalation. He allowed the outside world to become nothing, the interior not much more than that. He sought a state of semi-consciousness, in which his awareness of the mundane was blunted, and his perception of those things less mundane equivalently sharpened.

Beside him, the silver plumb upon its silver chain swung gently in the light evening breeze that blew up across from the moor before him. Presently it stopped moving with a sudden shudder and hung canted at an angle of some twenty or so degrees from the vertical. Slowly, quivering as if base iron in a strong magnetic field, it swung degree by degree upwards further still, up until it was pointing directly into the centre of the large, low basin before him.

Cabal was unaware of it, but that didn’t matter. The tripod was not some manner of indicator, although it could fulfil that role, too. It was more in the nature of bait.

Somewhere far, far away and yet so very close at hand, the note of a sword striking a sword sounded. Cabal heard it, but his eyes had sunk shut and he did not trouble to open them. Not yet. The time was not yet.

A scream now. A single solitary scream of mortal agony and the fear of death brought close and immediate. It died away, as the man who had once screamed it must also have died away. The whinnying of terrified horses rose in a faint chorus, borne to him on the breeze. The clang of swords, both great and broad, echoed above it, the dull battering of a struck shield, the rattling of the horses’ tack and barding. Cabal’s face showed some small phantom of emotion. Specifically, disgust.

There was a sound like thunder, but it was the roar of cannon. Ancient artillery firing in an ancient battle. Cabal’s pupils could be discerned through his eyelids as small bumps in the skin, and these bumps swung high and around. Cabal was rolling his eyes.

The individual sounds grew together, forming a soundscape, an auditory painting in action. Men grunted, horses snickered, blows were given and taken, warriors killed and died. The timbre grew, the sounds became more distinct, the silver pendulum pulled so hard towards the sounds, so filled with unnatural vivacity, that only the fact that the tripod’s legs ended in spikes driven into the sod kept it upright at all.

When the phantom battle was all but bellowing in Cabal’s face, he deigned to open his eyes.

And there it was in all its spectral glory, the great battle of Perkis Moor more sharply defined than any man or woman had ever seen, this thanks to the precision of Cabal’s preparations. Men-at-arms clashed with knights, musketeers of the English Civil War engaged Roman legionaries, naked men painted in blue woad charged Napoleonic artillery pieces and were duly cut down by grapeshot. It was, in purely historical terms at any rate, bollocks, just as the archaeologists had always said. It was also, just as they had said, very exciting indeed if one’s job consisted of watching sheep for lengthy periods.

Perhaps once, a very long time ago, there had been some small fight here. Not even necessarily a fatal one. Perhaps Og of the stone tribe had grunted something needlessly deprecatory about Ug of the fur tribe’s mother, and Ug—who loved his mother dearly although not in the manner alluded to by Og—had struck him smartly in the face, putting him on his arse with a split lip.

In the retelling, the blow had become a fight, the fight a skirmish, the skirmish a battle, a pebble of truth gathering the moss of invention as it rolled down the years. And people were so stupid, they couldn’t tell one period from another. Cabal had once seen an early medieval Bible lovingly illustrated with men and women dressed in clothes contemporaneous with the age in which it was created. Jericho was shown being besieged with siege engines a thousand years out of their time. In uncountable minds’ eyes down the centuries, the Battle of Perkis Moor was fought in whatever best pleased the daydreamer. Knights in gleaming armour to please the heart of Malory, soldiers of the War of the Roses, swords and spears, crossbows and muskets, rocks and rockets.

It hardly mattered; all that was important was that the device worked. He wasn’t even convinced that the drug had been necessary and would try the operation again the following evening, this time without. In the meantime, the drug hadn’t so purged him of reason that he couldn’t be judgemental of the sideshow for fools playing out before him. This was the least of examples, he was sure. One clumsily glued together by generations of unimpressive intellects. He was after greater fare. Out there were five particular sites, and his suspicion was that they had been created deliberately by methods that escaped him. Not that he needed to know, of course. He had no great interest in replicating such things, only in exploiting them. Exploiting five. It was no small undertaking. They would be cathedrals of the intellect as compared to Perkis Moor’s small mud hut.

In a single movement Cabal took up the tripod and slid home its legs against a stone, closed it, flicked some small fragments of soil adhering to the spikes clear with a gloved finger, and put the device back into his bag. As he did so, the battle suddenly attenuated, its combatants thinning out like magic lantern projections when the curtain is drawn back and the daylight re-enters the room. Now they looked like ghosts, and now they looked like suggestive shapes in the evening mist rising from the damp land, and now they were gone altogether.

Cabal cared not a jot. His main concern was how on earth he was supposed to entertain himself for a full day in a place as devoid of interest as Perkis Moor. After all, it was only haunted, and the ghosts were boring.

* * *

A week later, two mourners stood by an open grave in a concrete field, and looked down upon a glass coffin that held a beautiful corpse.

‘My God,’ said one, dead himself. ‘She’s perfect. Just as she was.’

‘I made no mistake,’ said the other, dead himself once, half-dead on enough occasions to be worth several more extinctions. Yet now he was living and vital, because some people are just jammy like that. ‘I have never made a mistake where she was concerned. At least,’ and here he paused and frowned at painful memory, ‘no mistake in method or theory. There are other mistakes possible, however. The metaphysics of my endeavours are far from clear or simple.’

The first man, a monster by some authorities, a good chap by all the rest, smiled a sympathetic smile. ‘You speak of the morality of it?’

‘I do.’ The second man was only considered a monster by the law and most churches, and who were they to judge him, anyway? ‘It used to be simple. She is dead, therefore I move heaven and earth to save her.’

‘Simple…’ echoed the other.

‘And yet, despite the clear practical problems involved in my practises, it transpires there are philosophical matters to consider, too. Once I discounted philosophy as a pastime for earnest young men with unconvincing beards and the be-sweatered young women who hang upon their every word, for old men in barrels or on top of pillars. I have made war upon angels and demons and, worst of them all, humans to arrive at this juncture, and yet it was only recently that I realised there is a pressing question that I had never once addressed nor even considered.

‘Would she actually wish to be brought back to the land of the living?’

‘Those are heavy matters indeed,’ said the first, who was a vampire. A nice one.

‘Indeed,’ said the second, who was a necromancer.

They pondered in silence.

Finally, the vampire said to the necromancer, his brother, ‘Is “be-sweatered” actually a word?’

* * *

They replaced the great stone cover upon the concrete grave—and went to leave the hidden laboratory adjoining the cellar of the house of Johannes Cabal, the necromancer. As they left the laboratory and made their way through the cellar, the vampire, Horst, paused by a large barrel, a butt of the type popular for the drowning of dukes. This example, however, did not contain an awkward rival for the throne of Richard III pickled in Malmsey wine.

Horst laid his hand on the wood of the barrel’s head a little guiltily. ‘This seems very undignified in comparison.’

Cabal knew his brother well enough to detect the forced lightness in his tone; he did not comment on it. Instead he said, ‘Practicality was the concern. The barrel was handy, and undoubtedly made its … her transport across the Continent a great deal easier. It’s just as good a container as a glass coffin. Better, perhaps. It’s certainly a great deal less fragile.’

‘You’re not going to—’ Horst made vague gestures with his hands, as if pouring out a bucket—‘decant her, then?’

‘I am not,’ said Cabal. ‘Doing so would be a risky operation and for little gain beyond, I admit, the aesthetic. In any case, from what I know of Fräulein Bartos’s personality, I think she would prefer the barrel. Glass coffins are for fairy-tale princesses. Not someone as pragmatic as she.’

Horst nodded, reassured. It wasn’t necessary for his brother to explicitly state that Alisha Bartos had been a trained killer, practised agent, and decent conversationalist. Had been, and would be again if Johannes Cabal could keep his promise.

* * *

In an ideal world, the reader would have the common courtesy to have read all the previous novels in this series and retained sufficient of the plot that a pithy summation would be unnecessary.

As has been noted by observers more perspicacious than the author, however, it is far from an ideal world, and a distinct proportion of those reading these words will have had more pressing matters than to avail themselves of the four novels preceding this one. To these people, the author says, ‘Yes, four. You jumped in at Book Five. What are you like?’

Thus, it falls upon the author (as diligent and kind as he is handsome and effortlessly virile) to offer a brief summation of previous events to aid these readers—Who starts reading at Book Five, I ask you?—as well as those who have read the preceding novels and would simply like their memories refreshed.

Johannes Cabal was once very nearly a solicitor, but a kindly fate saved him from this terrible future by killing his best beloved. She drowned, should you be curious, or just morbid.

Grief stricken, Cabal refused to accept the generally accepted absoluteness of death, and instead turned to certain esoteric, occult, and highly illegal paths of possibility. One such path took him to a remote, shunned graveyard where he was forced to abandon his brother, Horst, in a crypt wherein dwelt a vampire. Horst destroyed the monster, but not before he was contaminated.

Thus, Horst vanished from the purview of man. Missing, believed dead (which was both true and not true), his loss splintered die Familie Cabal: his father sank into a dreadful melancholy that ended with his premature death; his mother denounced the younger and less favoured son, Johannes, before leaving England and returning to her birthplace in Hesse, Germany.

All of this troubled Johannes Cabal less than perhaps it ought. Rather than doing anything to rectify matters, he instead relocated the family house by curious means from the middle of a terrace in a provincial English town to a lonely hillside in open country, by which he gained the solitude necessary to continue his studies.

He gained the knowledge to perform such research and, indeed, commit wanton acts of urban redevelopment by the simple expedient of selling his soul. Presently it transpired that this was a mistake, and that his soul was actually of use to him. Using a potent mix of ruthlessness, immorality, deception, diablerie, and candyfloss, he was able to reclaim his soul. In so doing, he upset Satan. If only that were the only time he had upset a major otherworldly entity.

At least Cabal had recovered his brother, Horst, from the ancient crypt in which he had been abandoned, albeit for selfish ends. Unhappily, there were words and hurt feelings, and Horst died, utterly and finally.

Until he got better. This was as great a surprise to him as to anyone else. Resurrected by a shadowy conspiracy (as distinct, presumably, from one of those highly publicised conspiracies), Horst was put in the difficult position of asking his brother to help save the world from the machinations of the conspiracy in general and of its prime mover in particular, a woman of means, intellect, and profound wickedness known as the ‘Red Queen’.

To his surprise, Johannes seemed older (this was because he was older), wiser, and altogether more human than Horst remembered, his experiences having mellowed him at least a little. He readily agreed to help Horst and his allies, and the world was saved. Saved again, strictly speaking, as it turned out Johannes Cabal had done it a couple of times before, usually by accident.

The victory was not without sacrifices, however. One such was Alisha Bartos, currently perfectly preserved by a strange chemical in a large barrel. Horst had developed a fondness for her—she had once shot him, then apologised nicely—but more pressingly felt responsible for her death.

Nor, however, was the victory without spoils. Johannes Cabal had recovered a book so rare that he had believed every copy had long since been lost or destroyed: The One True Account of Presbyter Johannes by His Own Hand.

This, you may rest assured, is a very important book. Why that should be has not been revealed to date, but probably shall be sooner rather than later. After all, Johannes Cabal, a necromancer of some little infamy, has rested much stock upon it and enthused in uncharacteristically vigorous terms how it changes everything without actually being overly specific about why that should be.

And so, we are up to date. If you have read the previous novels, I hope that has successfully refreshed your memory. If you have not, and have just lurched in here like a drunk into a cinema half an hour after the programme began, sit down and shut up. You are disturbing the patrons.

We may now continue.

* * *

The grandfather clock chimed midnight as they emerged from the cellar door and made their way to the front parlour. Cabal was nocturnal by habit (it was when the cemeteries and graveyards were most fruitful for his visits) and Horst by nature (sunlight caused him to burn rather than tan; burn in a brief moment of incandescence leaving naught but dust and regrets).

Horst was taking things as restfully as possible, delaying the inevitable moment when needs be he would seek blood. Even when that happened, he would take it carefully, a jigger here, a mouthful there, so as not to inconvenience anyone. His brother’s material needs were less troublesome, and he went to the kitchen to assuage them with a pot of Assam tea and a plate of cold meat and pickles.

Horst sank into his favourite armchair and awaited Cabal’s return. While he waited, he regarded the deep alcove by the fireplace and the high shelf there. Upon it was a row of three wooden boxes, each large enough to contain a human head. This is not a fanciful metric; two did contain human heads and the third something head-like that may well have been a head. Johannes Cabal was cagey on the subject of its contents. Whatever it was, it had a good singing voice. To the right of it was the living skull of the hermit and sage Ercusides, whose voice was a little reedy, but he tried all the same, bless him. The third box contained the living head of Rufus Maleficarus, although his was not the spirit that animated it. That was an entity of awful malevolence that had sought on several previous occasions to bring the apocalypse to earth, that loathed Johannes Cabal with a savage intensity, and that couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket. Now it was forced to occupy the head of a former rival of Cabal’s, and spent its days sulking, voicing threats and imprecations, and utterly failing to hit even middle C with any reliability. The thing in the first box’s hopes for, with the addition of a hypothetical future fourth box, a barbershop quartet had foundered on the head of Rufus Maleficarus massacring ‘Carolina Moon’.

For the moment, however, the boxes were quiet but for a quiet burring snore from the second and subdued spasmodic expletives from the third.

Cabal returned with his supper. As he arranged his plate and saucer to his satisfaction upon the table, he noted Horst’s languid gaze up at the shelf. ‘The erstwhile Herr Maleficarus turns out to be as poor a loser in the afterlife as he ever was when he had a body beneath his neck,’ Cabal commented. ‘His father was no better.’

‘You decapitated him, too?’ Horst’s tone was no more astonished than if his brother had suggested he had taken up golf. Far less so, in fact.

‘I did not. I don’t make a habit of that, you know.’

Horst regarded the row of boxes. ‘Of course you don’t.’

‘There is a certain degree of coincidence with regard to living heads in my line of work, I’ll grant you. Still, they are hardly unknown in occult circles. Bacon’s head of brass leaps to mind, for example.’

‘Hmmmm.’ Horst was not agreeing, as he had no idea as to whom Cabal referred. He was, however, remembering that he had once liked bacon and grieved privately that it could no longer be part of his diet.

‘So,’ he said, stirring himself from memories of bacon sandwiches past, ‘has that book turned out to be as useful as you thought it would be? Are the secrets of the universe there unveiled?’

‘No,’ said Johannes Cabal.

‘Too easy, eh?’

‘Too easy. I’m sure I have impressed upon you in the past what the word “occult” actually means?’

‘You have. It means “hidden”.’ He saw Cabal’s raised eyebrow. ‘You see? I do listen. Now and then.’

‘Much of that “hidden” quality is not on the part of nature, or the supernatural. Wizards, sorcerers, witches, and oracles have seen things for which the common herd are neither prepared nor tolerant. For their own safety, such people are inclined towards secrecy. I can only sympathise; many of my more potentially … contentious—’

‘Incriminating…’

‘—notes are enciphered for exactly those reasons.’

‘So Presbyterian Jack’s big book of magic is in code, is that what you are saying?’

‘Presbyter Johannes, often called Prester John.’

‘Let’s call him Prester John to avoid confusion.’

‘Quite, yes. That would be sensible.’ Cabal stirred his tea and took a sip. ‘It isn’t exactly enciphered, but it is in code. It uses allegory and allusion to hide its truths, mostly very esoteric imagery. Highly arcane. I have been working to squeeze sense from it.’

Horst could see this was no more than the truth. Cabal’s sunken face and darkly rimmed eyes betokened near exhaustion. Horst was dead to the world during the hours of light and could not know what his brother did in that time, but it seemed to contain little enough sleep.

‘You should rest, Johannes.’ He said it gently. ‘You are no use to anyone if you burn the candle at both ends.’

‘I have no time for rest.’

‘Make some.’ The gentle tone slipped a little, leaving something steelier in its place. ‘Don’t make me compel you.’

Cabal looked up sharply at him. ‘You wouldn’t dare.’

‘I’m still the elder of us, even if you’re the one who looks older now. I won’t watch you work yourself to death, especially having brought you back from the brink once recently already. I have better things to do than nurse you through another convalescence.’

‘Don’t even joke about exerting any of your … talents upon me, brother. I do not take well to coercion.’

There was an awkward silence. In truth, Horst had indeed used his vampiric powers to force his brother into deep recuperative sleep when he had been seriously ill some weeks before. This, he would never tell Johannes. For his part, Johannes had strong suspicions that Horst had done exactly that. This, he would never tell Horst. He was damned sure he would never permit it while in good or, at least, moderate health, however.

Cabal coughed. ‘In any case, it would be an unnecessary measure. I have wrung what truth I can from the book. I am reasonably confident that I have all of it. I shall attend to my health and well-being at this point. You are, quite accidentally, right for once. The trials I foresee shall require my constitution to be at a peak.’

Horst, who had been slouching back with his hands behind his head, sat up. ‘Trials? What do you mean? I thought that book was meant to be the be-all and end-all. The Philosopher’s Stone, you called it. The Fountain of Youth.’

‘So I believed. I was wrong, but in some ways right. I have told you of my time in the Dreamlands?’

Horst nodded. ‘Zebras.’

‘Of all the aspects of that long and perilous journey, your first thought is of the zebras. Yes, then. The place with the zebras. The nature of the Dreamlands is that they are formed from the will of sleepers, not all benevolent, not all human. It is concrete enough, but mutable, and that mutability is a function of belief. The Dreamlands gain much of their permanence from being what they are anticipated to be.’

‘Yes,’ said Horst slowly, uncertain as to the relevance.

‘The waking world impinges upon the Dreamlands. Indeed, many physical entities may gain entrance directly to them. Ghouls, for example.’ Here a glimmer of fond remembrance passed across his face. ‘And gods.’ The glimmer vanished. Cabal stared at a cold cut of beef and its pickled red cabbage accompaniment as if he held it personally responsible for some tragedy in his life. He sighed. ‘The point is that what is not, may be, and that which is, may not.’

‘Oh,’ said Horst.

They sat in silence for a minute.

‘You have no idea what I’m talking about, do you?’ said Cabal.

‘Not a sausage.’

‘I am trying to say, in words of as few syllables as possible, that the principles of the Dreamlands hold some sway in the waking world. They may even be extrusions. This latter point I do not know, and nor do I care to find out. That they exist is all that matters.’

Now Horst started to get an inkling of what his brother was proposing, and his expression was suitably startled at the revelation.

‘Hold on. Are you suggesting that there are places in the world that don’t actually exist?’

Cabal looked at him coldly. ‘If you say, “Like Norwich,” or similar, I shall not be responsible for my actions.’

Horst seemed insulted. ‘The very thought.’

He had been about to moot Swindon.

‘As I say, I do not know whether these locations are outposts of the Dreamlands or simply called into being by a similar process. It hardly matters. They will not be found on any map, that much I know. They exist in between the here and the now, edge on like the blade of a knife. If you don’t know where to find them, you never shall.’

‘How did this Prester John fellow find all these places?’

‘He didn’t.’

‘He wrote a book about it.’

‘He didn’t exist. He never existed.’

Horst took in this intelligence with difficulty. ‘How did he manage to write a book, then?’

‘You’re forgetting that of which I spoke earlier. Allegory and allusion. Have you ever heard of Prester John before?’

Horst shrugged. ‘I don’t know. I think I have, probably. Sounds familiar. Something to do with the Crusades, wasn’t he?’

‘Yes. Gold star.’

‘I would ask you not to patronise me,’ said Horst, ‘but that would be like asking you not to breathe. Carry on.’

‘Simply put—’

‘Thanks ever so…’

‘Simply put, he was the great hope of Christian Europe when the Moslems were being such a threat to them in the thirteenth century. They had the Holy Lands, they had spread along North Africa and into Spain, and there was the real possibility that they would spread further still. The Crusades were partially about reclaiming the Holy Lands in general and Jerusalem in particular, but the core of their purpose was to halt the threat. It was a real threat, too. The forces arrayed under the crescent were far more coherent than those under the cross. The royal houses of Europe had spent so long bickering and warring amongst themselves, they were taken by surprise by an external threat. They were desperate.

‘So, when a rumour of a previously unknown Christian empire in the East started to circulate, people were desperate enough to believe in it. An empire under a Christian ruler popularly known as Prester John, who had successfully defeated the Moslem in the East, and now wished to ally himself with Europe to fight the Moslem in the West.’ Cabal drank some tea. ‘A shame, then, that he didn’t exist, and neither did his empire.’

‘That must have been a bit of a blow.’

‘You know how the Crusades turned out. Yes, I think we can safely say it was a bit of a blow. That didn’t stop people believing in Prester John, however. It didn’t stop them from wanting to believe. A letter was delivered decades later, claiming to be from the same Prester John. You see how wishful thinking starts to develop supernatural overtones? In this letter, the author describes “his” empire. It is full of the most remarkable wonders, including’—and here Cabal paused dramatically—‘the Fountain of Youth.’

‘So the Fountain of Youth doesn’t exist?’

‘Did I say that?’

‘You said Prester John’s empire didn’t exist.’

‘I said Prester John didn’t exist. Attend more closely, Horst.’

Horst huffed with exasperation. ‘May I just say that I am very confused at this juncture?’

‘That is why I am a scientist and you are a fop. Now, the Orient was becoming less of a mystery to Europeans by this time, and its lands were being mapped. Cartographers looked around and saw there was no possible place that this marvellous empire could possibly exist, and reported as such. This, again, constituted “a bit of a blow”.’

‘So, that was it for the legend of Prester John…’

‘No.’

‘No?’ Horst’s expression was of somebody trying to play a game wherein the other player keeps ‘remembering’ rules that tip things in his favour.

‘No. They just looked for another bit of terra incognita and stuck it in there instead. The mysterious empire of Prester John and all its marvels did a moonlight flit. Popular delusion lifted it bodily from the Orient and placed it in Africa instead. So, you see the significance of the book’s title now?’

Horst looked like he’d been slapped with a halibut. Cabal pressed on regardless.

‘The One True Account of Presbyter Johannes by His Own Hand is not about Presbyter Johannes at all. His legend is used as an extended allegory to hide from the ignorant and illuminate to the wise that such places of such potentiality actually exist. The wonders listed in the letter purporting to be from Prester John are not parts of a single empire; they are all pockets of ontological happenstance. Including…’

He looked keenly at Horst. For once, his brother did not disappoint him.

‘The Fountain of Youth?’

Cabal smiled a smile of harsh satisfaction. ‘And what is youth if not vitality? What is it if not life?’ The smile faltered. ‘My tea’s gone cold.’

* * *

This was not the most glamorous job they had ever been engaged upon, but for the two men lurking in shrubbery just below the crest of the hill, nor was it the worst. They were encamped on the other side of the hill, and only lit a fire during the hours of darkness, its light baffled by an impromptu wall of stones, its smoke hidden by the night. They had food for a few days, and supplemented it with locally caught rabbits, roots, and berries. They were used to living rough, and the English countryside was a great deal less rugged than the Katamenian forests to which they were accustomed. It was, therefore, something of a busman’s holiday to them, used as they were to living hand to mouth, waylaying strangers, and avoiding the law. All they had to do was keep an eye on the house across the valley from their encampment and, should the owner leave, go to the nearby village and report the fact by telegram. Leave, that is, with luggage. Their leader, their employer, their owner was not interested in trips to buy a bottle of milk and a loaf. These were logged in haltingly formed letters scrawled into a notebook, but were of insufficient import for concern. If, however, he left with luggage including—probably—something coffin-sized and likely at night, they were to report this with alacrity. It did not do to fail in orders, not even in the slightest detail. Their employment was profitable, it was true, far more than they would have believed possible even a year before. But the other side of the coin was a level of discipline to which the wise had adjusted quickly.

It was after all a dangerous, even fatal, mistake to disappoint the Red Queen.

* * *

‘The book details…’ Cabal paused to reconsider his words. ‘The book implies methods by which these splinters may be located.’

‘Are these like pocket universes, Johannes?’ Horst had his best serious face on, and it was a reasonable question. ‘Like that one with the drizzle and the croquet?’

‘You remembered that? No. Not really. The Eternal Garden and its cousins—’

‘That place has a name?’

‘It does. I just coined it. The Eternal Garden and its cousins are constructs, very deliberately created by wit, wile, and a lot of mathematics. The splinters of reality to which the book refers are more natural in their creation. They are literally the stuff of legend. The creations of a mass gestalt, not necessarily—as I hinted earlier—of human intellect. They are of a feather to the hidden places of the fey, and share many of the same dangers.’

‘Oh, goody,’ said Horst. ‘I was wondering when we’d get onto the dangers. Come on, then. What are we likely to encounter?’

Cabal was pleased that his brother was so engaged upon the project at hand that he easily used ‘we’ when describing the approaching travails. He gave no indication of that pleasure, however. It would never do to give Horst the impression, truthful though it might have been, that he both required and wished his brother’s involvement.

‘The usual. Monsters, deathtraps, riddles, plentiful opportunities for derring-do.’

‘What an interesting definition of “usual” you have…’

‘It isn’t by choice, brother. These are places created, as much as anything, by an unconscious yearning for the impossible, and the certainty that any fruit worth the taking will not be easily plucked. We shall be confronting the results of millennia of human ingenuity, wilfulness, and malice. Nor just that of humans. We shall tread in the shadows cast by campfires and their stories, of the tales of minstrels, of every idiotic blood-soaked fable told by an elder sibling to terrify the younger.’

Here Horst scratched his jaw, and regarded Cabal from under a censorious brow. ‘You’re not still looking under the bed before retiring, are you? Anyway, given your line of work, I’d have thought that was a good habit to get into. Lord only knows what ghosties and ghoulies and long-legged beasties you’ve stirred up in your time.’

‘I tend to shoot them at the time of stirring. It saves later unpleasantness.’

‘Never put off an unpleasantness until tomorrow when you can be unpleasant today?’

Cabal shrugged. ‘In principle, yes. There is another consideration.’

‘Thank heavens. It was all beginning to sound so easy.’

‘The Lady Ninuka.’

Horst sat up suddenly. ‘The Red Queen?’

‘I suppose she’s a de facto queen, now. Queen Ninuka of Mirkarvia. That country seems to have no luck at all. If only you had slain her while you had the chance.’

It was an unwise thing to say. ‘I didn’t have a chance. You weren’t there. Don’t be so bloody ignorant.’ Horst sank back into a louring attitude, unusual for him.

Cabal belatedly remembered something he’d come across once. It was called ‘diplomacy’ and it was, in principle, lying as an instrument for making people feel not quite so ill done to. This would seem to be an ideal situation on which to ply such a discipline, as it occurred to Cabal that not only had Horst failed to kill Ninuka, which was embarrassing enough, but that the woman Alisha Bartos, currently to be found occupying a barrel in the cellar, had died in that encounter, and that Horst may have harboured some sort of emotional attachment to her. Perhaps diplomacy was the correct tactic to employ at that moment, Cabal concluded. Thus steeled in his intent, he hazarded an attempt at this exciting new conversational form.

‘It wasn’t your fault,’ he said, and rested from his labours.

It didn’t seem to have entirely worked. ‘I didn’t want to kill Ninuka, anyway. That’s not the sort of person I am, Johannes. I’d, y’know, sort of had vague ideas of arresting her. Capturing her. The Mirkarvians have been hurt by her far more than anyone else; they deserved to put her up on trial. If they want to string her up at the end of it, that’s their concern. I’m not some sort of executioner.’

Cabal was hardly listening. Horst had entirely failed to appreciate the delicacy and elegance of his utterance and was instead blathering about failing to kill Ninuka. Holding down his exasperation at his brother’s arrant twittery, he said, ‘No, no. I wasn’t talking about Ninuka. I was talking about you getting the Bartos woman killed.’

The short pause that ensued was more than sufficient to assure Cabal that there was far more to this ‘diplomacy’ malarkey than he had perhaps given credence.

‘Not that you did,’ he added.

Horst’s anger flared across his face and passed in a flicker to be replaced by a dour acceptance that this was his brother he was talking to, and the lifetime of making allowances that this betokened.

‘That’s your idea of diplomacy, is it?’ he asked. Cabal shrugged; perhaps. ‘Let’s just skip that whole unhappy episode and get back to what you were saying, shall we?’ Cabal shrugged; yes, let us do that.

‘Notes. There were none. Ninuka’s scientific library was … idiosyncratic, to say the least. About a third of the books made no sense in context. Popular histories, dreadful calumnies, much the same where necromancy is concerned. They had no place there. The rest, however, were sensible choices, including a couple of rarities.’

‘Like the Prester John book?’

Here Cabal paused and seemed troubled. ‘No. It is a great rarity to be sure. Indeed, the only extant copy as far as I know. But, it is not a book of necromancy. I only recognised its great utility to my researches due to a great deal of reading and peripheral references.’ He looked deeply perplexed. ‘It has taken me years to reach that point, Horst. Is she really such an extraordinary prodigy as a necromantrix that she arrived at the same conclusion so much more quickly and then was able to actually procure this rarest of texts?’

‘It’s … possible?’ said Horst, deploying the meanest slivers of tact under the circumstances. If he meant to sting his brother by the unavoidable implication, he was disappointed. Cabal was too wrapped up in conjecture to notice.

‘Possible, of course. Probable … its probability concerns me. What I understand of Ninuka’s intelligence is that, while she is by no means stupid, her nous is not of the academic variety. Indeed, before she was—’

‘Provoked?’ offered Horst.

‘—inspired to take up necromancy by—’

‘You murdering her father?’

‘—circumstances, she seemed to have no scientific interests at all. Apart from a very specific branch of biology, at any rate.’ He glanced at Horst, whose left eyebrow had risen on a tide of curiosity. ‘You would have liked her then.’

‘Ah,’ said Horst, to whom all had become clear.

‘From Lady Bountiful to an evil fairy-tale queen in a single bound seems prodigious.’ He nodded, conceding the point. ‘But not impossible.’

‘You should be proud, Johannes.’ Horst’s tone was hardly conciliatory. ‘She is your creation, after all.’

At this, Cabal coloured slightly, but then subsided quickly. ‘Unkind, but true, I regret to say. Most of my more malignant creations are more easily dealt with, too.’

‘I doubt she’s going to succumb to a few sharp blows with a retort stand, no.’

‘Oh, she probably would. Getting within a country mile of her with a retort stand is the issue. I digress. The point I was making is that her notes were nowhere to be found in her laboratory. Whatever she had culled from her books and her researches is contained within them, and those notes represent the nucleus of the threat she represents.’

‘Threat? What threat? She’s in Mirkarvia, we’re in England’s green and pleasant land. She’s a long way away.’

Here Johannes Cabal furnished his brother with a look that spoke of disappointment largely with himself at trying to talk to Horst when he could be talking to some lichen, which would probably understand the situation better.

‘She’s very rich, ruthless, and motivated. Mirkarvia really isn’t that far away when one has access to at least one fast air vehicle. I doubt the Catullus is the only thing she appropriated from the Mirkarvian aeronavy, either. If she but knew of this house, a stick of bombs descending upon it from a cloudless sky would be a likely outcome. And don’t tell me that she wouldn’t risk the ire of the Royal Aeroforce by doing so; losing a ship would be a small price for her as long as she was not aboard.

‘I don’t believe revenge is her main concern at present, however. She must know I have Presbyter Johannes, and that will inform her actions. She knows I shall attempt to seek out the Fountain of Youth, be it actual or figurative. She will attempt to beat me to it. I am sure of it.’

‘But you don’t know where it is.’

‘I know several places where it might be. They will have to be investigated until the correct one is found.’

‘How many is “several”?’

‘Five, scattered across Europe, Asia, and Africa.’

Horst blanched. ‘That will take years!’

‘Months, but too many months. Given her resources, Ninuka will almost certainly find the majority before us.’

Horst rose and paced up and down. ‘Well, here’s a pretty problem.’

‘Not at all. If the sites are explored sequentially, yes. If, however, two expeditions go forth, then I think that tips matters back in our favour.’

Horst stopped in his pacing. ‘We split up? I’m not sure that is a very good idea, Johannes. For one thing, there’s the way I tend to burst into flames in daylight. That’s limiting. And, to be honest, I’m not sure I’d recognise a knife-thin sliver of a conjectural reality if it bit me.’

Cabal smiled at him or, at least, the furthermost point of his mouth rose. ‘Trust you to do this by yourself? Ever the joker, Horst.’

‘Thanks.’ Horst said it without a reciprocating smile.

‘No, there will be physical danger, and there will be challenges of an intellectual nature. You can surely handle the former, but with all due respect…’

He did not finish the sentence, nor did he need to.

Horst sat down heavily and crossed his arms.

‘In truth, I have the opposite problem. There are things in this and others worlds that are unimpressed by even a Webley .577. What I propose, therefore, are two teams of two. We shall procure the services of somebody able to look after themselves and me into the bargain for one duo, and somebody with perspicacity, wit, and intelligence to make up for your shortcomings in those attributes to join you in the other.’

Horst shrugged off the slurs upon his intellect with brotherly ease. ‘That’s another quest in itself, surely? By the time you’ve found these paragons, we might as well have tried to do it all ourselves in any case.’

‘I know where to find them already,’ said Cabal. ‘That is not the hurdle. Persuading them is the rub. Well, for one, at least. The other will certainly prove more enthusiastic.’

At this point, Cabal’s face did a strange thing, a sudden flexion and tautening that was brief, but that filled his brother with wonder.

‘Did you just smile? I mean, really smile? Not one of those things you call a smile that frightens donkeys, but a real, actual smile?’

To which Johannes Cabal said nothing, but the ghost of that fleeting expression glowed upon his countenance for some time after.

* * *

It was an unassuming cottage overlooking an unassuming little market town, but it was homely and comfortable and a pleasant enough place in which to spend one’s retirement. It had once been visited by a small bit of elemental evil that had disported itself around the fireplace and almost resulted in a death and a damnation, but that was years ago, and one has to let these things go ultimately, doesn’t one? The reminders crop up now and then, and dreams sometimes colour into nightmares at what almost was and what awful thing might have been. The day comes, and the half-remembered blows away, dust on the breeze. The calamity did not come to pass. The agent of evil turned out to be wrought with internal conflict. The last hope was fruitful.

Still, for all this, Frank Barrow was only momentarily surprised when that agent reappeared on his doorstep, bearing flowers, a bottle of decent wine, and asking curtly if politely if his daughter, Leonie, happened to be in residence. This moment of surprise passed easily from Barrow to Cabal, as he punched the necromancer a beautiful right straight to the jaw that felled him like an ox introduced to a poleaxe.

Barrow stood over Cabal, fists up and furious. ‘Get up, you bastard! Get up so I can knock you down again!’

Cabal blinked to dispel stars, but was only partially successful. He tried his jaw with his hand to make sure it was still there. Remarkably, it was; retired he might be, but ex–detective inspector Francis Barrow was still not a man to invite into a physical contretemps lightly.

‘I shall stay down here in that case,’ said Cabal. ‘I have no desire to be knocked down again.’

Here, Barrow made the shade of the Marquess of Queensberry very sad by kicking his opponent in the ribs. Cabal, however, had not lived as long as he had without allowing for contingencies. Mr Barrow being rather put out to see him had not even been a very unlikely one. Cabal reached inside his jacket and, when his hand reappeared, it bore a businesslike semi-automatic pistol of Italian pedigree. This he aimed at Barrow’s head in a manner that implied a second kick would be unwise.

Barrow backed away a step. ‘Why have you come back, Cabal? You’re not bloody welcome here.’

‘So I gather.’ He took up the bottle—unbroken due to a fall into a rose bed—and the bouquet—dishevelled, but still presentable—in his off hand and showed them to Barrow. ‘I brought peace offerings. I understood that was the done thing.’

‘Cabal?’

Frank Barrow looked back. In the corridor behind him stood his daughter, Leonie, her unruly blond hair temporarily corralled in a ponytail. ‘I’ll deal with this, love,’ he said. He might have been talking about a dog’s leaving upon the garden path.

‘Fräulein Barrow,’ said Cabal, ‘always a pleasure. I would rise, but your father has promised to knock me down again.’

‘You’re pointing a gun at him, Cabal.’

‘I am, yes.’

‘Last time I saw you, you were pointing a gun at me then, too, you pallid bastard,’ said Barrow.

‘So I was. You’re right; it’s unfriendly. I shall suggest a compromise. I shall put the gun away, and you do not kick or punch me or otherwise do me harm. Is that acceptable?’

It was barely that. Barrow stood pale and almost quivering with rage over Cabal’s prone form. It was left to Leonie to say, ‘Yes, it is. Dad, step away from him, for heaven’s sake.’

‘What?’ Barrow swung his head to face her, disbelief in his eyes. ‘You can’t want to take this evil bugger’s side?’

‘I’m not taking anyone’s side,’ she said. ‘But look at the pair of you. I don’t want to have to clear up any blood. You’re all set to beat him into a pulp, and believe you me, I know Cabal would shoot you without hesitation. I don’t want to have to deal with any corpses today, thank you. We have enough trouble getting the dustbin men to take away extra rubbish at the best of times.’

Barrow knew his daughter of old, and so backed down first. He made a show of unclenching his fists and nodded at Cabal. ‘Put yon gun away. I’ll not hit you. Though God knows you deserve it.’

More quickly than he might once have done, Cabal accepted Barrow’s acquiescence. He smartly aimed the gun away, lowered its hammer, re-engaged the safety catch, and returned it to its holster. ‘May I get up now?’

Barrow snorted, which was the closest to an affirmative he felt like giving at that moment. Cabal carefully and without sudden moves climbed to his feet. He addressed Leonie. ‘I brought wine. And flowers. You may wish to place them in a vase. With water. They are already dead in any real sense, but the water will preserve the appearance of life for a little longer.’

Leonie accepted them despite a warning glance from her father. ‘Why, Mr Cabal. How romantic. Please, come in.’

‘Leonie!’ Barrow stepped into Cabal’s path as he tried to follow her into the house. ‘This is my house and that … man is not coming in. Have you forgotten what he did? What he is?’

Cabal’s eyes narrowed suspiciously. ‘You speak of the carnival?’

‘Of course! What else?’

Cabal leaned slightly to look at Leonie past Barrow. ‘You haven’t told him?’

Barrow’s brow fogged with confusion. ‘Haven’t told me what?’ he demanded of his daughter.

She smiled at him, a little weakly.

* * *

It took longer than it needed to, to tell Frank Barrow of the fact that Leonie, his daughter and only child, had actually met Cabal twice in the intervening years, and had kept it from him because, ‘I thought it would upset you.’ In this, she was absolutely correct.

‘Twice?’ Barrow was not sure what he ought to be most horrified by; that she had met Cabal again on two occasions that might reasonably be described as fraught, that she had kept this intelligence from him, her own father, or that she had come away from these encounters with a growingly positive view of a man whose business included body snatching and consorting with supernatural minions of diabolical evil. He inwardly decided it was all pretty ghastly and said as much at regular intervals, hence the reason the history of the aeroship the Princess Hortense and the curious business of the Christmas at Maple Durham took so long to recount.

Throughout these recollections, Cabal remained quiet, less due to consideration of Barrow’s pained feelings as a desire not to get punched again. A painful jaw and some bruised ribs spoke volubly that Barrow’s feeling towards him were not the finest. Even where his recollection of events differed from Leonie Barrow’s or where he disagreed with her interpretation (the latter was the more common), he maintained a silence birthed of self-preservation.

When she had at last finished, there was a heavy silence that Cabal punctured by saying, ‘Would anyone like a glass of wine?’

‘The kitchen’s through there,’ said Leonie with a nod. ‘Corkscrew’s in the cutlery drawer by the cooker. Wine glasses are in the cabinet over the worktop.’ Cabal rose uncertainly and went to fetch them. As he reached the door, she added, ‘Take your time.’

Barely was the door shut behind him when he heard Barrow’s voice lift. ‘How could you? He’s a bloody monster!’

‘He was a monster,’ he heard her reply, and he was inexplicably heartened by this. He set off to find the corkscrew and glasses, and he took his time doing so.

He found them immediately, and dawdled for a few minutes, watching the day dim though the kitchen window as the sun touched the horizon. When the voices from the parlour had diminished from full rancour to an aggrieved resentment communicated in mutters and sharp rejoinders, he judged the time right to return.

‘I’ll be mother,’ said Leonie, taking the corkscrew from Cabal and using its blade to break the wax around the bottle’s cork. Barrow occupied the time by glaring at Cabal, Cabal by finding almost everything in the room of interest with the exception of Barrow’s face if the line of his wandering gaze was to be believed.

Leonie passed a filled glass to Cabal and slid one to her father across the tabletop when he seemed not to notice it proffered to him.

‘My daughter,’ said Barrow in clear syllables that brooked no interruption, ‘tells me that you’re not such a bastard any more.’

Cabal shrugged modestly. ‘Well, I—’

‘My daughter,’ said Barrow, ‘tells me you don’t work for … a certain entity any more.’

‘That was more of a temporary arrange—’

‘My daughter,’ said Barrow, ‘tells me that you have done good.’

Here, Cabal paused. Yes, he had done good. By accident, as a by-product, by serendipity. But yes, he had done good. He just didn’t see why people kept wanting to rub his nose in it.

Unsure how to answer, he said nothing, and inadvertently seemed modest by it. All unaware, he sat cloaked in unwitting humility.

Barrow took up his glass. ‘All right, then. Let’s hear it.’ Cabal looked inquisitively at him. ‘What are you doing here, man?’

* * *

Explaining the concept to Horst had taken long enough. Horst, for his part, was a moderately intelligent man who was also a vampire; a man who had encountered werewolves, döppelgangers, creatures from beyond the veil of our reality and a fell beast that was half-man, half-badger. He was alive, or at least undead to the possibilities of the eldritch. Frank Barrow was a former police officer who lived in a cottage, and to whom the only thing he might consider truly unusual in his life had consisted largely of Johannes Cabal and the travelling entourage he nominally managed at the time.

He still cottoned on to what Cabal was asking faster than Horst had, and Leonie was a few seconds ahead of him.

‘The secret of life itself?’ said Barrow. ‘That’s what you’re after?’

Cabal raised his hands modestly. It was a modest enough goal, after all.

‘But you have no idea what form this secret might take?’ added Leonie.

‘None. The text from which I am working is long on symbolism, short on detail. It may be a principle. It may be a literal fountain. I tend towards the former view.’

‘And what will you do with this secret, assuming there even is a secret, and assuming you get your grubby little paws on it?’ Frank Barrow was still not convinced that Cabal was anything other than the soul-stealing huckster he had once been and made few pains to hide it. ‘Sell it? Use it for nefarious ends?’ Barrow had once heard a chief constable speak of nefarious ends and been impressed by the phrase. Whatever these ends were, they sounded like they were an end unto themselves, self-contained little parcels of villainy that malefactors collected as a scout collects badges.

Cabal started to reply, but was overcome by nonplussedness for a moment. When he recovered his wherewithal, he asked, ‘What sort of “nefarious ends”, exactly?’

Barrow grimaced at such sophistry. Inwardly, he imagined one nefarious end being The Commission of Arson Using Only Two Matches. ‘You know full well what I’m talking about.’

‘In the first instance, Herr Barrow, you may have been led astray by my activities when first we met. I am not usually engaged in business, not even the running of a carnival. Money matters little to me. I only seek to save someone.’

‘Who?’

‘That,’ said Cabal, a little steel showing in his voice, ‘is my concern. You need not worry that I intend to raise some dreadful dictator or similar from the grave. Politics concerns me fractionally less than business, and business concerns me not at all.’

‘Not good enough. You can’t expect my daughter to go along with your schemes without so much as a hint as to the reason for it all.’

‘I don’t need to know,’ said Leonie. ‘You’re a man of honour, Dad. I’ve always respected that. Well, this is my honour, and Cabal … Mr Cabal saved my life. I owe him a debt.’

Cabal shook his head. ‘No. I make no claim upon any such debt, not least because you saved my life, too.’

‘I did?’ Leonie looked astonished.

‘You could have reported me to the authorities at any point. I doubt my life would have seen out an hour subsequent such a denunciation. That is by the bye. Even if a debt did stand, I cannot impose upon you to help me in this undertaking from any sense of obligation. There will undoubtedly be danger. I hope and trust the goal will be more than worth any such peril, but the peril will be real, nonetheless. You must make your decision based upon whatever merits you see in this enterprise.’

‘And if I think it’s a fool’s errand?’

‘Then you would be a fool to agree.’

‘Very well.’ Leonie sat back, cosseting her wine glass. ‘Convince me. Why should I help?’

‘Simply put, because lives depend upon it. Two lives.’

Leonie glanced at her father and back at Cabal. ‘That’s not some sort of ham-fisted threat, is it?’

Cabal was silent for a moment while he digested the implication. ‘No, no. As I think I said to your father once, I really do not care for threats very much. Warnings, perhaps, but threats, no. The lives to which I allude are already extinguished. Unfairly, and before their time.’

‘Life’s unfair,’ said Barrow. He regarded his hands clasped together on his lap, anything to avoid looking at the picture of his wife on the mantel. ‘Death twice as much. You can’t go gallivanting around undermining eternal verities just because they happen to nark you off a bit.’

‘Two questions, Mr Barrow. Firstly, why ever not? All science is based on the precept that we know too little. Ignorance is not bliss. It is only ignorance. Its bed partner may be the inertia of the conservative. Often it is only fear. If death may be cured, why should we regard it as anything different from curing the common cold, or cancer? Secondly, if an eternal verity turns out to be neither eternal nor true, why defend it? It is said that death and taxes are the only inevitabilities in life. It is, I understand, meant in a jocular manner, but nevertheless, if there was some miraculous economic formula that meant you never had to pay a penny in taxes ever again, yet there were no dreadful repercussions, no collapse in public services, would you not rush to embrace it?’

‘That’s chalk and cheese—’

‘Is it? What, then, is your objection?’

‘This thing you’re looking for, it’s against nature.’

‘If the mechanism exists, it is part of nature. By definition, it cannot be anything but natural.’

Barrow’s face flushed. ‘It’s against God’s law.’

It was possibly not the best argument to employ against a necromancer. Still, by a remarkable feat of self-control and a mental image of Horst slowly mouthing the word Diplomacy, Cabal managed not to burst out in peals of bitter laughter.

‘Mr Barrow, I appreciate that God’s opinion probably matters a great deal to you, but—truly—He doesn’t care. If the object of this quest is against God’s notoriously morphic and ill-defined law, it wouldn’t exist. The only promise we have from the mouth of that deity worth spit is that of free will and self-determination. Everything else is open to negotiation.’

‘You’re a blasphemous bugger, Cabal.’

‘I’m rational, unlike your God. Really, when has He ever stuck to His word?’

Barrow smiled grimly. Finally, Sunday school was going to prove its worth. ‘The Flood. God promised never to do it again.’ He crossed his arms. ‘And He never has.’

Cabal was underwhelmed by this argument. ‘Really. And when somebody drowns in a natural flash flood, say, what’s that? A white lie? No, Mr Barrow, the only time your God takes a blind bit of notice of you is when you die. Either you go off to the petty sadist in the other place—’

‘You mean the devil? Satan?’

‘The devil, yes. Satan, I’m no longer so sure. I’m beginning to think it’s a job description rather than a personality.’ He waved an impatient hand, as if wafting away a cloud of dumbstruck theologians. ‘But that is neither here nor there. Or, as I was saying, you end up in the personal collection of the entity you call “God”. He … it chamfers off any awkward corners that might indicate bothersome traces of individuality, and stacks the homogenised souls into the eternal equivalent of pigeonholes.’

Barrow flinched at Cabal’s description of Heaven. ‘You can’t know that.’

‘I know enough to know God does us no favours. The heavenly afterlife is very much what atheists have long suspected: nothingness. Where they are wrong is that it isn’t the simple cessation of all sensation and awareness, but the engineered nothingness of an entity who hates mess and fuss. Consciousness … poo. Will … won’t need that. Memories of life and love and everything … tiresome. God is not your friend. God has never been your friend.’

The room grew quiet.

‘Perhaps,’ said Leonie, ‘perhaps working to undermine my father’s faith wasn’t the best way to talk me into coming along.’

‘Wasn’t it?’ Cabal thought about it, and salted that information away for some future date when it might come in useful. ‘Oh.’ He nodded at Frank Barrow. ‘Well, he started it, believing in nonsense.’

‘Not an improvement. Look, Cabal, you’re setting about this all wrong. I’m not very interested in having you gain the secrets of life, whether it be bringing back the dead in a way that doesn’t involve brain-eating, or potentially immortality. For one thing, just think what it’ll do to the population figures.’

‘I wasn’t planning on marketing it…’

‘I appreciate that. No matter what, it’s not my concern. It has never been my concern.’

‘Ah.’ Cabal picked up his glass as if considering finishing the drop of wine at the bottom, but put it down again undrained. ‘I’m sorry to hear it, Fräulein Barrow. I am sorry I’ve wasted your time. Mine, too, but I regarded it as necessary.’ He rose awkwardly. ‘I shall see myself out.’

Leonie watched him complacently. ‘You’re adorable when you do that, you know? Your injured-pride face would melt a puppy.’

Cabal’s expression was uncertain; he had seen a molten puppy once, and it hadn’t been that adorable.

‘Sit down,’ she said. ‘We’re not done yet.’

‘With respect, Fräulein Barrow, I understood that we were. You do not wish to help me. I shall have to look for aid elsewhere.’

‘I said nothing of the sort. You forget, Cabal, I’m a scientist myself.’

‘Criminology, I believe?’

‘You remembered.’ She smiled a sweet smile like icing on a razor. ‘I have my own interests. For one thing, bringing back the dead would make my job a lot easier. Or, I admit, obsolete.’ She adopted a poor workable Cockney accent. “Orright, Bert, ’oo did you in?” “It were ’im, guv’nor! Stabbed me to death good and proper an’ dropped me in the river. I’ll swear to it in court.”’

She observed conflicting expressions on the faces of Cabal and her father, the former somewhat taken aback by the amateur dramatics, the latter suddenly remembering a few old cold cases from his career that might finally be brought to book by this development.

‘But that’s not what I’m talking about in this case. These fragments of myth of yours, Cabal. They exist?’

‘I believe so, yes. I believe so very strongly. I have seen variants of the same mechanism; these “fragments” are hybrids of the two. The only reason that they are not generally known is because they are not easily discovered or entered.’

‘Now they fascinate me.’ She shrugged. ‘Who wouldn’t be by the thought that our world contains such things, like reading a novel and finding pages of another book mixed in?’

‘It’s dangerous,’ both men chorused and looked at one another.

‘Life is brief, opportunities to see the extraordinary are rare. It’s not as if I’ll be by myself, Dad. Cabal here is a rare survivor. If I have his word that he will not abandon me, that’s good enough for me.’

‘Ah,’ said Cabal slowly. ‘That’s not quite the plan.’ He looked out of the window. Beyond the net curtains, dusk deepened.

‘It isn’t?’ said Leonie.

‘Not quite. Pardon me a moment.’

Cabal rose and left the room. They heard him go to the door and open it. Frank and Leonie Barrow heard Cabal speak in lowered tones. A voice, male, answered him. The Barrows looked at one another with cautious surprise. A moment later Cabal re-entered the room.

‘I should like to introduce you to my brother, Horst,’ he said.

A tall man in his early twenties, handsome, pale, and with curls of light brown hair curling out from beneath his hat stepped into the room. He was dressed well in a suit of black with flashes of imperial purple at the breast pocket and lapels, the left of which bore a clove-red carnation as a boutonnière. He doffed his hat, and bowed to the Barrows.

‘Hullo,’ said Horst. ‘More of a reintroduction, I think? We’ve met before.’ He smiled, and his eye teeth seemed somewhat pronounced, yet it was no less charming a smile for all that. ‘Hullo.’

* * *

It took a week to settle matters. Frank Barrow spent two full days of this trying to talk Leonie out of what he sincerely believed to be a disastrous decision. To his every argument, she would smile consolingly and answer with a counterargument that always, reduced to its most fundamental terms, ran thus: ‘Science.’

To this, he had no response.

When it became apparent that no appeal to intellect, sympathy, or sentiment (he was too good a man to resort to emotional blackmail, no matter how profoundly he feared her loss) would dissuade her, he instead turned his attention to improving the odds of her safe return. The first step of this was when, on the morning of the third day, he came to her bearing, not argumentation, but a well-crafted but undecorated box of pale, varnished wood.

They sat together at the breakfast table, and he opened it. Inside lay a .38 revolver in a shaped covert lined with green felt. Around it, also snuggled into slots and alcoves, were the accoutrements of maintenance, and six live rounds.

Leonie looked at it for a long moment, expressionless. Then she took it up to examine it. ‘Webley Mk.1,’ she said. ‘Cabal would approve. He usually carries a Webley .577.’

‘I’m not giving it to you for his bloody approval.’ It disconcerted him to see a firearm in his daughter’s hands, frightened him, and he sat down to forestall the desire to take it from her. She was a grown woman, after all. She had an M.Phil and was working on a Ph.D. She wasn’t his baby any more. Would never be his baby again.

‘I thought you didn’t like guns, Dad.’

‘I don’t. Bought that after … after the last time.’

He didn’t clarify this, but he didn’t need to. The last time Cabal came into our lives.

She weighed the weapon in her hand a moment longer, and returned it to its case. ‘It’s a kind thought, Dad, but I’m not taking this.’

‘You need to be able to protect yourself. God only knows what sort of mess that maniac wants to drag you into. A vampire!’ He looked around helplessly, as if something in the kitchen would appreciate his discontent. ‘A bloody vampire he’s got you running off with!’

‘Horst seems nice enough,’ said Leonie carelessly. ‘He never wanted to become one.’

‘Oh? So how did that happen? Caught vampirism off a toilet seat or something?’

‘No. I think it was his brother’s fault. Some experiment or something that went wrong.’

‘Cabal made his own brother into a blood-sucking monster? Well, that makes me so much more confident about the whole thing now. If only he’d said, I’d have offered to go along myself.’ He paused. ‘I should go with you.’

‘Dad, we’ve been through this. You’re in your sixties, now, and—be honest—you’ve not kept yourself in the best condition.’ Barrow looked down at his gut glumly; even his own adipose was betraying him. ‘Cabal’s a planner. He doesn’t take risks he doesn’t have to. And, when all’s said and done, Horst is a blood-sucking monster, yes, but he’s our blood-sucking monster. I’ll be safe.’

‘I’d be happier if you had a gun.’

‘Dad.’ She sat opposite him and took his hands in hers. ‘I’ve got a gun.’

Barrow’s mouth dropped open. ‘You’ve what?’

‘Senzan 8mm automatic. The man sold me a box of dumdums under the counter.’

‘Dumdums? Bloody hell! How long have you had that?’

Leonie shrugged. ‘Bought it after … after the last time.’

She didn’t clarify this, but she didn’t need to. The last time Cabal came into my life.

* * *

The brothers Cabal were staying in the next town, as they were not remembered entirely fondly in Penlow on Thurse where the Barrows lived. There had been the business with the exploding carnival, the giant ape, the demons, and so forth. It had even made the front page of the Penlow Reporter; FUSS CAUSED, screamed the headline on the story. THREE NOISE COMPLAINTS RECEIVED. Admittedly it had been a sidebar to a more pressing story about a small fire in a hayrick that had been put out quite quickly. They took their hayricks seriously in Penlow on Thurse.

So, Johannes Cabal had taken a room in a bed-and-breakfast establishment while Horst found a fairly comfortable and long disused tomb in the local cemetery, and the two brothers waited, one more patiently than the other. Finally, a telegram of acquiescence arrived, and Cabal met Leonie at the Penlow railway station, a station the railway company had been astonished to discover was not as decommissioned and demolished as their records showed and so quietly returned it to the schedules. Somebody had clearly blundered and, on the off chance it was somebody important, it was better to just let things be.

Cabal was pleased—perhaps even very pleased—to see Leonie, less so to see her father.

‘Mr Barrow,’ he said. He didn’t trouble himself to fabricate even one of his least convincing smiles for the greeting. The two men understood one another completely.

Frank Barrow placed the end of one fingertip a quivering sixteenth of an inch from the tip of Cabal’s nose.

‘One hair. So much as one bloody hair on my daughter’s head is harmed, and I will hunt you down to world’s end. Do you understand me?’

‘Of course.’ Cabal took a half step back to remove his nose from the finger’s proximity. ‘And you should understand that no part of my plans involve anyone getting hurt.’

‘You just look after her.’

‘I shall not. My brother shall. He is to be her bodyguard and to sport his not inconsiderable abilities as and when they are required.’

Barrow’s eyes narrowed. Horst struck him as possibly a bit of a lady’s man, vampire or not. ‘What sort of abilities?’

‘Strength, alacrity, mesmerism, acute senses. He’s rather impressive; I don’t say that lightly.’